13.1: Early Byzantium

- Page ID

- 108676

About the chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire

by Dr. Evan Freeman

This essay is intended to introduce the periods of Byzantine history, with attention to developments in art and architecture.

Since this book divides the Byzantine Empire into three chronological slices and presents each with contemporaneous medieval cultures, it divides this article in three segments. Middle Byzantium will appear alongside Ottonian and Romanesque Europe and the Islamic world up to the Mongol invasions. Late Byzantium will appear alongside the Crusades and the rise of Islamic hegemony from the Adriatic east through India.

From Rome to Constantinople

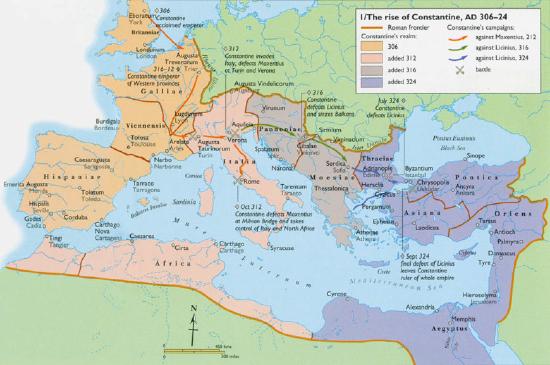

In 313, the Roman Empire legalized Christianity, beginning a process that would eventually dismantle its centuries-old pagan tradition. Not long after, emperor Constantine (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) transferred the empire’s capital from Rome to the ancient Greek city of Byzantion (modern Istanbul). Constantine renamed the new capital city “Constantinople” (“the city of Constantine”) after himself and dedicated it in the year 330. With these events, the Byzantine Empire was born—or was it?

The term “Byzantine Empire” is a bit of a misnomer. The Byzantines understood their empire to be a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire and referred to themselves as “Romans.” The use of the term “Byzantine” only became widespread in Europe after Constantinople finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. For this reason, some scholars refer to Byzantium as the “Eastern Roman Empire.”

Byzantine History

The history of Byzantium is remarkably long. If we reckon the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from the dedication of Constantinople in 330 until its fall to the Ottomans in 1453, the empire endured for some 1,123 years.

Scholars typically divide Byzantine history into three major periods: Early Byzantium, Middle Byzantium, and Late Byzantium. But it is important to note that these historical designations are the invention of modern scholars rather than the Byzantines themselves. Nevertheless, these periods can be helpful for marking significant events, contextualizing art and architecture, and understanding larger cultural trends in Byzantium’s history.

Early Byzantium: c. 330–843

Scholars often disagree about the parameters of the Early Byzantine period. On the one hand, this period saw a continuation of Roman society and culture—so, is it really correct to say it began in 330? On the other, the empire’s acceptance of Christianity and geographical shift to the east inaugurated a new era.

Following Constantine’s embrace of Christianity, the church enjoyed imperial patronage, constructing monumental churches in centers such as Rome, Constantinople, and Jerusalem. In the west, the empire faced numerous attacks by Germanic nomads from the north, and Rome was sacked by the Goths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455. The city of Ravenna in northeastern Italy rose to prominence in the 5th and 6th centuries when it functioned as an imperial capital for the western half of the empire. Several churches adorned with opulent mosaics, such as San Vitale and the nearby Sant’Apollinare in Classe (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), testify to the importance of Ravenna during this time.

Under the sixth-century emperor Justinian I, who reigned 527–565, the Byzantine Empire expanded to its largest geographical area: encompassing the Balkans to the north, Egypt and other parts of north Africa to the south, Anatolia (what is now Turkey) and the Levant (including including modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan) to the east, and Italy and the southern Iberian Peninsula (now Spain and Portugal) to the west. Many of Byzantium’s greatest architectural monuments, such as the innovative domed basilica of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, were also built during Justinian’s reign.

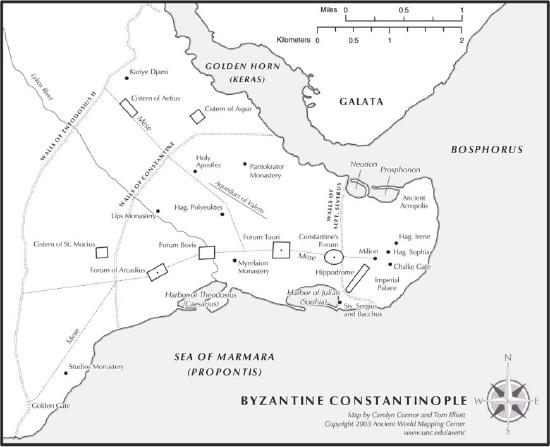

Following the example of Rome, Constantinople featured a number of outdoor public spaces—including major streets, fora, as well as a hippodrome (a course for horse or chariot racing with public seating)—in which emperors and church officials often participated in showy public ceremonies such as processions.

Christian monasticism, which began to thrive in the 4th century, received imperial patronage at sites like Mount Sinai in Egypt.

Yet the mid-7th century began what some scholars call the “dark ages” or the “transitional period” in Byzantine history. Following the rise of Islam in Arabia and subsequent attacks by Arab invaders, Byzantium lost substantial territories, including Syria and Egypt, as well as the symbolically important city of Jerusalem with its sacred pilgrimage sites. The empire experienced a decline in trade and an economic downturn.

Against this backdrop, and perhaps fueled by anxieties about the fate of the empire, the so-called “Iconoclastic Controversy” erupted in Constantinople in the 8th and 9th centuries. Church leaders and emperors debated the use of religious images that depicted Christ and the saints, some honoring them as holy images, or “icons,” and others condemning them as idols (like the images of deities in ancient Rome) and apparently destroying some. Finally, in 843, Church and imperial authorities definitively affirmed the use of religious images and ended the Iconoclastic Controversy, an event subsequently celebrated by the Byzantines as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.”

Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Early Byzantine period

by Dr. Alicia Walker

The mosaic depicting the sixth-century empress Theodora and her retinue in the church of San Vitale (Ravenna, Italy) shows the empress’s attendants dressed in multicolored, luminous garments with repeating patterns indicative of woven silk.

Although rendered in mosaic, a medium in which Byzantine craftsmen held unrivaled expertise, the image depicts Byzantine courtiers as consumers of an intercultural market of luxury goods. At the time this mosaic was executed, the empire had not yet mastered sericulture (the cultivation of silkworms), which required special conditions to raise mulberry bushes, the sole source of food for the silk moth (bombyx mori). Both the raw material of silk and the cloth woven from it were imported at great expense from points east, especially China, which held a virtual monopoly in silk cultivation and processing. Women of the court were among the few members of Early Byzantine society who could afford this lavish material, which demonstrated not only wealth but also privileged access to circuits of trade. Similarities among Sasanian, Early Byzantine, and early Islamic textiles indicate that silk weavings across these cultures shared not only material characteristics but also iconographic, stylistic, and technical features. The interconnectedness of Byzantium with other societies through trade, diplomacy, and military conflict had direct bearing on the development of Byzantine art and architecture, and Byzantium also impacted the formation of other late antique and medieval artistic traditions.

In the early fourth century, when Constantine I was named emperor, the Roman-Byzantine Empire extended throughout Afro-Eurasia (the landmasses and interconnected societies of Africa, Europe, and Asia), from Britain in the northwest to Syria in the East and across the coast of North Africa in the south.

The Roman-Byzantine Empire participated in extensive trade and diplomatic contacts with a wide range of societies, such that the period has been characterized as one of “incipient globalization.” [1] In the fourth to fifth centuries, Northern Eurasian migratory groups vanquished the western provinces of the Roman Empire, even sacking Rome itself. [This is part of the Migration Period discussed later in this chapter.] Early modern European historians overinterpreted the late antique and medieval eras as a “Dark Ages,” focusing on breakdowns in long distance communication and supposed declines in cultural achievement in Western Europe while ignoring the vital, cosmopolitan cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East. During this period, the eastern Roman-Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople, weathered centuries of periodic geo-political instability, socio-religious change, and economic crisis, all the while maintaining and further developing commercial and diplomatic contacts across late antique and early medieval Afro-Eurasia.

A sense of the convergence of military might, cultural identity, and exotic goods is conveyed by the so-called Barberini Ivory, discussed later in this chapter.

The triumphant emperor on horseback at center receives blessings from Christ, above, and a gesture of subservience from Ge (the personification of Earth) below. Yet the image also asserts the emperor’s dominion through the depiction of conquered peoples. A cowering figure behind and to the left wears the quintessential costume associated with depictions of late antique “Persians” (that is, Sasanians): leggings, a knee-length tunic, and a pointed cap. He touches the emperor’s standard submissively. Below, foreign peoples (Persians, Indians) in their distinctive dress bear tribute for the emperor, including a diadem, exotic animals, and an elephant tusk. The latter detail inflects the viewer’s appreciation of the polyptych itself, which is fabricated from ivory that was likely traded via Aksum, a Christian kingdom (located at the intersection of modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Yemen) that was a major actor in trade between the Mediterranean, Africa, and India. In the Early Byzantine era, ivory was sourced from India and Africa, where elephants were indigenous. The Barberini polyptych, therefore, embodies in its very materiality the ideals of universal might and intercultural control of precious resources conveyed in its iconography.

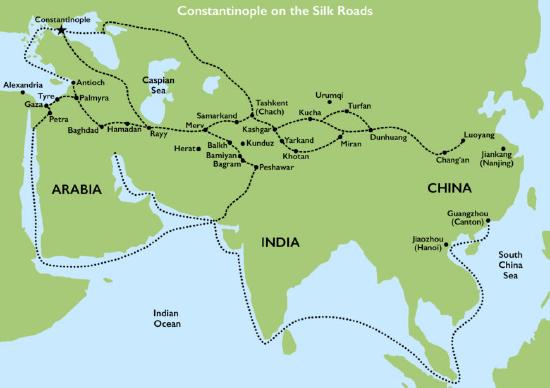

Silk textiles, like those worn by Theodora’s attendants in the mosaic at San Vitale (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)), were among the foreign goods most coveted by the Early Byzantine elite. Desire for silk, spices, precious stones, and other luxury commodities anchored Constantinople as the western terminus of the so-called Silk Roads.

Objects and raw materials—as well as artistic ideas and forms—traveled back and forth along these routes by land and sea from Europe and Africa to the eastern edges of Asia. Early Byzantine silks, glass, and coins have been discovered in graves and treasuries from Britain to China—and even in Japan. Sixth- or seventh-century Byzantine silver vessels with control stamps discovered in the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at the site of Sutton Hoo (Suffolk, England) bespeak the westward circulation of Byzantine objects in this period. Rosette motifs on these bowls (Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)) may have been interpreted by Anglo-Saxon viewers as a sacred tree motif, thereby bridging Christian and pagan Anglo-Saxon iconographic traditions. [2]

Early Byzantine efforts to secure the borders of the Empire sometimes involved alliances with foreign peoples. For example, the Arab-Christian kingdom of the Ghassanids was a client state of the Early Byzantine Empire. In the sixth and seventh centuries, they assisted in defending the Roman-Byzantine Empire against Sasanian and Muslim adversaries. Similarly, the nomadic Avars, who originated in the Eurasian Steppe, were allies of the Early Byzantine Empire. They received substantial gifts in the form of Byzantine coins and precious objects (and engaged in raids to obtain additional booty). The Avars were skilled metalworkers and also produced their own works of art in imitation of Byzantine models. The so-called Ewer of Zenobius (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) is a silver vessel inscribed in Greek around its neck. It may have been fabricated in a Byzantine workshop and then gifted to an Avar leader or it may have been produced (or altered) by Avar craftsmen who emulated Byzantine artistic techniques, control stamps, and/or inscriptions.

As the Byzantines lost their eastern territories to encroaching Islamic armies in the seventh century, the Muslim political and military elite inherited Roman-Byzantine visual and material culture in the lands they conquered. This is especially apparent in the desert villas constructed in regions settled by the first Islamic dynasty, the Umayyads (see Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)). The extensive wall painting program in an early eighth-century bath house at the Umayyad residence of Qusayr ‘Amra (in modern Jordan) employed a rich array of Roman-Byzantine iconography, including astronomical imagery, portraits of Byzantine and other early medieval rulers, hunting scenes, and depictions of bathers.

The famed early Islamic shrine known as the Dome of the Rock was modeled after Early Byzantine commemorative structures and is decorated in an elaborate program of mosaics and marble revetment that in part emulates Byzantine models and may even have been created by Byzantine craftsmen.

Although it is common today to associate global networks with the modern period, intercultural connections were also a vital part of ancient, late antique, and medieval experience in Afro-Eurasia. The Byzantine Empire communicated with diverse cultures and societies, and the art, architecture, and material culture of Byzantium and its neighbors attest eloquently to this interconnected reality.

Notes:

[1] Anthea Harris, ed., Incipient Globalization?: Long-distance Contacts in the Sixth Century (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007).

[2] Michael Bintley, “The Byzantine Silver Bowls in the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial and Tree-Worship in Anglo-Saxon England,” Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 21 (2011): 34–45.

The Vienna Genesis

by Dr. Diane Reilly

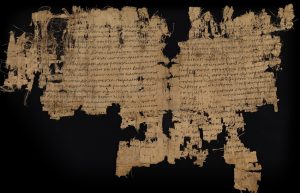

Wealthy Christian families living in the Byzantine world may have aspired to own a new kind of luxury object: the illustrated codex (see )Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\). Before the invention of printing, all texts were written or carved by hand. In the ancient world, manuscripts (texts written by hand) were found on a variety of portable surfaces. In the ancient Near East scribes wrote on clay tablets. In ancient Egypt and the ancient Greek and Roman world, information could be stored temporarily on wooden tablets coated with wax. A more lasting solution was to use scrolls made of papyrus (Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)): fibrous reeds that were dried in overlapping layers and then polished with a stone to create a smooth surface. Authors of papyrus scrolls usually divided their work into sections based on how much text could be held on a single scroll, leading to the concept of “chapters.”

New materials, new possibilities

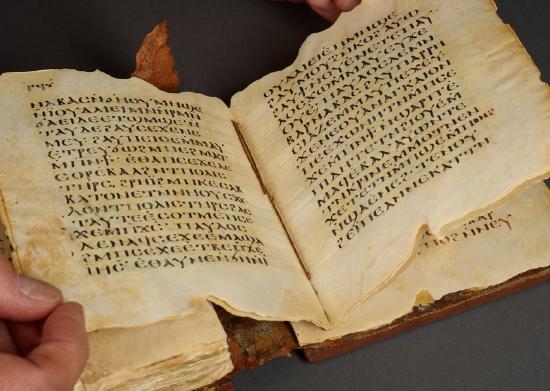

All of these materials preserved texts for the few literate members of the population, but the limitations of the materials themselves made it difficult to add illustrations to the text. Papyrus scrolls were rolled for storage and then unrolled when read, causing paint to flake off. Text was scratched into the surface of a wax or clay tablet with a stylus, so only basic shapes could be created. Some time in the first or second century, however, the parchment codex (Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)), a more durable and flexible means of preserving and transporting text, began to replace wax tablets and papyrus scrolls. The new popularity of the codex coincided with the spread of Christianity, which required the use of texts for both the training of initiates and ritual practices.

The codex form allowed readers to find a discrete section of text quickly and to carry large amounts of text with them, which was useful for priests who traveled from place to place to serve communities of Christians. It was also essential for a religion that relied on text to establish the details of belief and set standards of conduct for its members. The vast majority of these codices were not decorated in any way, but some contained illustrations done with tempera paint that pictured events described in the text, interpreted these events, or even added visual content not found in the text.

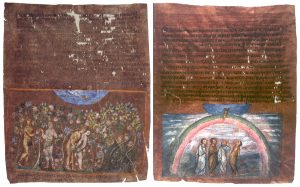

A luxurious codex

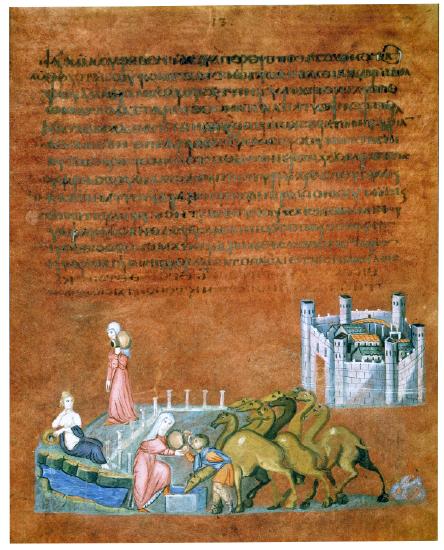

The Early Byzantine Vienna Genesis gives us a taste of what manuscripts made for a wealthy patron, likely a member of the imperial family, might have looked like. Genesis—the first book of the Christian Old Testament—described the origin of the world and the story of the earliest humans, including their first encounters with God.

The Vienna Genesis manuscript, now only partially preserved, was a very luxurious but idiosyncratic copy of a Greek translation of the original Hebrew. The heavily abbreviated text is written on purple-dyed parchment with silver ink that has now eaten through the parchment surface in many places. These materials would have been appropriate to an imperial patron, although we have no way of knowing who that was. The Vienna Genesis may have been a luxury item intended for display, or it may have provided a synopsis of exciting stories from scripture to be read for edification or diversion by a wealthy Christian.

Telling a story

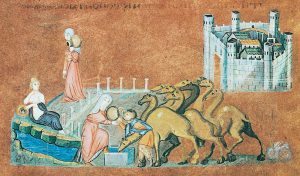

The top half of each page of the Vienna Genesis is filled with text, while the bottom half contains a fully colored painting depicting some part of the Genesis story. In the scene depicted, Eliezer, a servant of the prophet Abraham, has arrived at a city in Mesopotamia in search of a wife for Isaac, Abraham’s son. The artist has used continuous narration, an artistic device popular with medieval artists but invented in the ancient world, wherein successive scenes are portrayed together in a single illustration, to suggest that the events illustrated happened in quick succession. In the upper right hand of the image a miniature walled city indicates that Eliezer has arrived at his destination. Rebecca, a kinswoman of Abraham, is shown twice. First, she walks down a path lined on one side with tiny spikes that symbolize a colonnaded street. Rebecca approaches a reclining, semi-nude woman who allows an overturned pot to drain into the river below. This is a personification of the river that feeds the well to the right, where Eliezer waits. Rebecca is shown a second time offering Eliezer and his camels a drink, a sign from God that she is to be Isaac’s wife.

Ancient themes, new techniques

The personification of the river reveals the image’s classical heritage, as does the use of modeling and white overpainting which lend naturalism to the garment folds and the swelling flanks of the camels.

The Vienna Genesis combines pictorial techniques familiar from the ancient world with content appropriate to a Christian audience, which is typical of Byzantine art. Though many of the details of this manuscript’s production and ownership have been lost, it remains an example of how artists combined ancient modes of expression with the most current materials and forms to create luxurious objects for wealthy patrons.

An Angel in Ivory: Classicism and Christianity: A Conversation

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This conversation was recorded between Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker at the British Museum in London. Click here to watch the video.

Steven: We found a relatively quiet corner of the British Museum, which is not an easy thing to do.

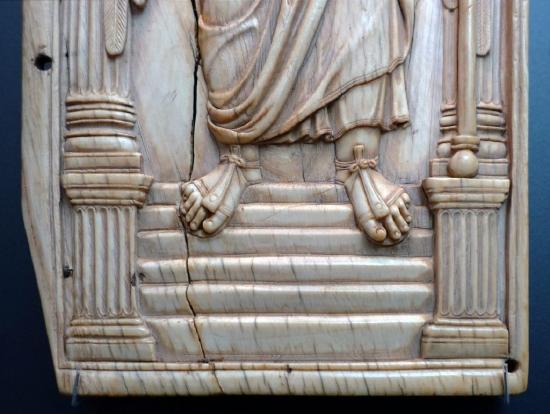

Beth: We're looking at a Byzantine ivory that dates to the sixth century.

Steven: And so, it's a small miracle that it's come down to us through history, because a moveable object like this is so easily destroyed.

Beth: And in fact, part of this was lost. This was originally part of a diptych. In other words, it was attached by hinges to another ivory panel with which it was related.

Steven: The thing that strikes a modern viewer first is the fact that this is an enormous piece of ivory. This came from the tusk of an elephant, and of course, right now in the 21st century, we're in a race to save elephants. And so, we look at this object with a different eye than we might in a previous historical moment.

Beth: But in fact, ivory carvings were common in the ancient Roman world and in the Byzantine world.

Steven: And ivory was treasured because of its smooth texture, because of its relatively hard but carvable surface. And ivory, especially at this scale, was a luxury object that was imported from Africa, from Asia, or sometimes it was the tusks of walruses or even of mammoths that had been uncovered.

Beth: This is one of the largest ivories to come down to us from the Byzantine period.

Steven: The frame is filled with the large figure of an angel, probably the Archangel Michael. He stands at the top of a stair under an elaborately carved arch, holding in his right hand an orb with a cross on it. And in the left, he holds a staff or a scepter.

Beth: We can tell that he's an angel because he has these beautiful, long wings. And that orb is a symbol of power. An orb is a sphere which might remind us of the sphere of the Earth, and on top of that, the cross. So this idea of the triumph of Christianity.

Steven: And this is one of the reasons that art historians believe that the other panel would likely have depicted the Emperor Justinian. Justinian was among the most powerful Byzantine emperors. And it's possible that this ivory was carved to commemorate his ascension to the throne.

Beth: Beneath the arch, a wreath of victory, and inside that wreath, the cross. So it's this interesting moment where the Roman Empire has moved east. It's lost much of its territory in the west, although Justinian does reconquer much of it. But this interesting blending of ancient Roman art traditions with the new Christianity of the Roman Empire, of the Byzantine Empire.

Steven: It's important not to flatten history and to remember how much time elapses between eras. Here we have the Byzantine looking back to the ancient Roman, and before that, to the ancient Greek. The classical era in ancient Greece began a thousand years before this panel was carved. And we see the echo of ancient Rome in the very way that the figure is represented and especially in the way that the drapery hangs over that body. This is a style of representation that is looking back to ancient Greece and ancient Rome.

Beth: That drapery reminds us of so many ancient Greek and Roman sculptures. The way that it clings to the body. We see the forms of the legs. We get a sense of where the hips are. The shoulders. We're drawn to that drapery and those lovely folds. Look closely at his left arm and the drape that hangs down and how you can see a shadow underneath it that gives us a sense of how deeply carved that is. I mean, this is so beautifully carved. This ivory really rewards close looking. The lovely fluting on the columns, the Corinthian capitals, which are so finely carved to really see those acanthus leaves, the little volutes at the top, and that lovely garland or ribbon that crosses the arch.

Steven: And the rosettes that fill the space on either side of the arch.

Beth: This was probably one of the most skilled craftsmen in the workshop of the emperor in Constantinople.

Steven: But for all of its classicism, that is, its references back to ancient Greece, to ancient Rome, we can't look at this panel and not be reminded that this is Byzantine. The artist is willing to play fast and loose with space. The figure seems not to stand on the stairs so much as to float above and in front of those stairs. The scepter is held by a figure that stands seemingly at the top step, and yet the scepter stands outside of the arch. And so the artist, like the figure, is no longer trapped by the naturalistic conventions of the classical world.

Beth: There are several translations of this inscription. The one that seems to be most commonly used is, "Receive this suppliant despite his sinfulness." So the person on the other side of the diptych is being welcomed by the angel that we see here into the court of heaven.

Steven: And so what we're seeing here is likely a commemoration of the ascension of an important figure to the throne, possibly Justinian, a Christian, but a Christian who is heir to the great Roman tradition.

Beth: And here we see the classicism of the Roman Empire in this Byzantine ivory likely made in Constantinople, today Istanbul, but which we are looking at here in the British museum.

The Emperor Triumphant (Barberini Ivory): A Conversation

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This artwork is called The Barberini Ivory because it became part of the collection of Cardinal Francesco Barberini in the early 17th century. It is also referred to as The Emperor Triumphant and as Justinian as World Conqueror.

This is a transcript of a conversation held at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Click here to watch the video.

Steven: We’re in the Musee du Louvre in Paris looking at a very large panel of ivory that is Byzantine and we date to the early 6th century.

Beth: These Byzantine ivories of this early date are very rare. There’s another one in the British Museum. This one shows an emperor on horseback in the central panel with four panels on the four sides, one of which is lost.

Steven: What’s remarkable to me is just how deeply carved and how energized the central panel is. There’s been tremendous care in representing not only fine details but also alternations between areas of deep carving and broad smooth areas, for instance of the horse’s body. This is so clearly an illustration of this moment of transition between the classical tradition and the Byzantine as we will come to know it. Should we start at the top?

Beth: Sure, we’ve got Christ in a medallion in the center with angels on either side. He makes a gesture of blessing and around him is a symbol of the sun, of the moon, and a star.

Steven: He holds a scepter with a cross and looks directly out at us. You can see that he’s been rendered not with the traditional long, thin face with a beard, but he’s young, he’s beardless and his hair is curly, which is very reminiscent of the classical tradition.

Beth: Those two angels are very reminiscent of Nike figures, of figures of victory that we would see in Ancient Roman carving.

Steven: Although the drapery has been simplified and is now rendered by cuts rather than fully formed folds. And below this dynamic image of the emperor riding in on a horse toward us, an emperor who is a Christian. We can see him holding the reins as he turns the horse, planting his lance down on the ground. Look at the round forms of the horse’s breast, or the leg that comes out and the way that the rein pulls the horse’s head back in. There seems to be such a sensitivity to creating a sense of volume, to establishing space for this foreshortened horse to occupy.

Beth: Art historians believe that the fineness of this carving indicates that this was made in a workshop in Constantinople in the capital of what we think of as the Byzantine Empire, but really was then the Roman Empire.

Steven: Now we don’t know who this imperial figure is, in fact we’re really just guessing that it is an imperial figure. But we feel like we’re on fairly firm grounds because of the fineness of the carving.

Beth: All the iconography is imperial. We have a Nike figure, a figure of victory presenting the emperor with a palm branch, a symbol of victory.

Steven: We guess that in her right hand she would’ve originally been holding a crown to place on his head.

Beth: As in so many other images of Roman emperors, nearby is the figure of a vanquished foe.

Steven: Look how that smaller figure behind the horse is represented. He’s wearing a Phrygian cap which was a symbol of the other, it was a symbol of the barbarian. He’s wearing pants, he’s wearing closed shoes. All of these things were symbols of the barbarian.

Beth: Barbarian here means foreigner, someone outside of the Roman Empire.

Steven: Now under the horse we see a female figure. She’s quite classicizing in the way that her drape has fallen off one shoulder. She holds in the folds of her drapery, fruits. So she becomes a symbol of plenty. Art historians think she represents perhaps conquered lands or the bounty of the earth.

Beth: We could see her as a personification of the earth submitting to the emperor by holding the underside of his foot.

Steven: If you look closely at the central panel you’ll see that there are areas where there would have been small gems or pearls. We can see the gem for instance between the eyes of the horse. But you can also see that there would have been many others that would have decorated the horse’s body.

Beth: So that central panel is in such high relief. Look at the drapery flying back behind the emperor. There’s a real sense of energy here that’s contrasted with the figure of, we think, a general, or at least a very high level officer who’s presenting the emperor with a statue representing victory.

Steven: So that general is represented in much shallower relief and we can see that he’s in a truncated architectural space. resides on earth, under god in heaven.

Icons, an introduction

by Dr. Evan Freeman

What is an icon?

In our time, we often refer to celebrities as cultural icons, pop icons, and fashion icons. Rebels are sometimes labeled iconoclasts. Icons are also the little images that populate the screens of our computers, phones, and tablets, which we click to open files and apps.

The word “icon” comes from the Greek eikо̄n, so, “icon” simply means image. In the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire and other lands that shared Byzantium’s Orthodox Christian faith, “holy icons” were images of sacred figures and events.

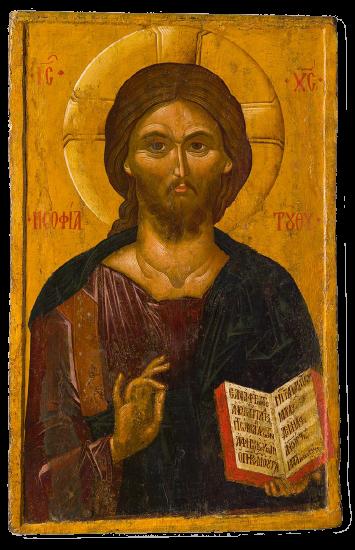

When art historians talk about icons today, they often mean portraits of holy figures painted on wood panels with encaustic or egg tempera, like the tempera icon of Christ from fourteenth-century Thessaloniki (Figure \(\PageIndex{28}\)). But the Byzantines used the term icon more broadly, as this statement made by Church authorities in 787 CE shows:

Holy icons—made of colors, pebbles, or any other material that is fit—may be set in the holy churches of God, on holy utensils and vestments, on walls and boards, in houses and in streets. These may be icons of our Lord and God the Savior Jesus Christ, or of our pure Lady the holy Theotokos, or of honorable angels, or of any saint or holy man.

(Council of Nicaea II, 787 CE)

In Byzantium, icons were painted, but they were also carved in stone and ivory and fashioned from mosaics, metals, and enamels—virtually any medium available to artists.

Icons could be monumental or miniature. They were located in a variety of religious and non-religious settings, including as decoration on functional objects like the Eucharistic chalice in Figure \(\PageIndex{30}\).

And icons could depict a wide range of sacred subjects, such as Christ (Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\)), the saints, and events from the Bible or the lives of saints.

Iconoclasm and the “Triumph of Orthodoxy”

Christians initially disagreed over whether religious images were good or bad. Texts from as early as the second and third century describe some Christians using religious images, which they illuminated and adorned with garlands, but these practices were not universal or standardized. Church authorities often criticized these practices, which reminded them of customs associated with pagan Greece and Rome, where images of gods and emperors were widely venerated.

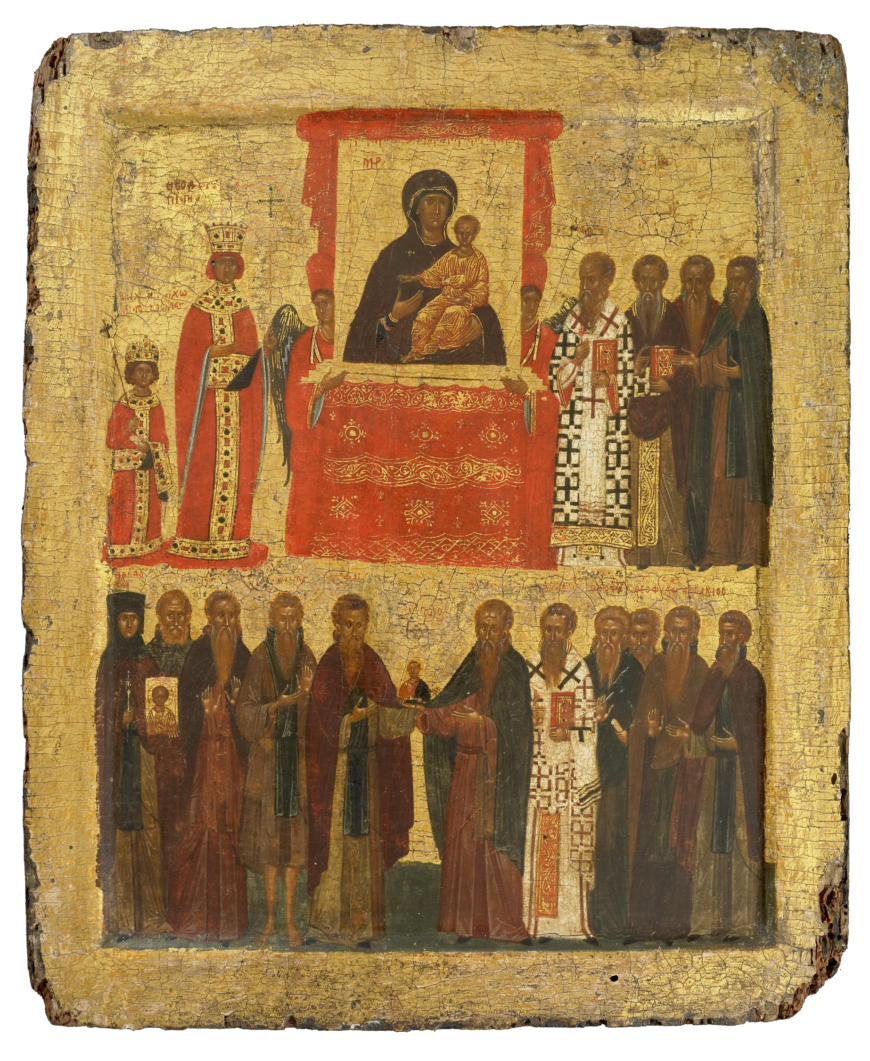

By the eighth and ninth centuries, icons were increasingly popular, and arguments about religious images boiled over in what is called the “Iconoclastic Controversy.” The so-called “iconoclasts” (literally, “breakers of images;” see Figure \(\PageIndex{32}\)) opposed icons, arguing that God was transcendent and could not be depicted in art. The iconoclasts feared that Christians praying before icons were worshipping inanimate objects.

On the other hand, the “iconophiles” (literally “lovers of images”), also known as “iconodules” (literally “servants of images”), defended icons, arguing that since Jesus, the Son of God, was born with a visible human body, he could be depicted in images. The iconophiles maintained that rather than worshipping inanimate objects, they honored icons as a means of honoring the holy figures represented in icons.

Imperial and Church authorities in favor of icons gathered at a council in the city of Nicaea in 787 to try to resolve the controversy, but it was not until 843 that the Church definitively affirmed the use of images, ending the Iconoclastic Controversy in what became known as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” To this day, icons continue to play important roles in the faith and worship of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which is heir to the religious tradition of Byzantium.

In addition to affirming Christian images, the 787 Council of Nicaea II and subsequent 843 Triumph of Orthodoxy also enshrined devotional practices associated with icons. Christians should bow before and kiss icons, light candles and lamps, and burn incense before them. All of these acts of devotion directed at images were intended to pass to the holy figures represented. As a modern analogy, we might consider the ways many people frame and hang photos of loved ones in their homes, sometimes even embracing or kissing such images.

This is an excerpt from a longer article, which continues after this point.

San Vitale, Ravenna: A Conversation

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This conversation was recorded between Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker in Ravenna, Italy. Click here to watch the video.

Steven: We're in the Italian city of Ravenna, standing outside of the Church of San Vitale. This is a really important 6th century church. It's just really old.

Beth: And it's unusual in that it's a centrally planned church. That means its focus is on its center instead of a basilica, which has a long, or longitudinal, axis.

Steven: Right. When we think about a church, we generally think about a building that's shaped like a cross. And it has that long hallway, the nave. This doesn't have that. Instead, it's got an ambulatory, or an aisle that surrounds its central space. In this particular case, on the east side of the church, there's also an extension with an apse at the end.

Beth: Looking at the outside of San Vitale, we see that it has eight sides. So it's an octagon. And within that octagon is a smaller octagon that rises higher.

Steven: The exterior of the church is brick. Those bricks were taken from ancient Roman buildings and reused here in the 6th century. The walls are pierced with lots of windows. And that's especially important because the interior is covered with some of the most magnificent mosaics that survive from the early Medieval period.

Beth: And of course, you'd want that light glistening on the gold and beautifully colored mosaics. Let's go inside and have a look.

Steven: We've walked into the church. And the center towers over us.

Beth: And yet these apse-like shapes that are supported by columns undulates and moves around us.

Steven: There are massive piers that help support the building. But there's also a real delicacy. Look, for instance, at the way that the columns are doubled, that is, stacking of one set of columns above the next.

Beth: And they move in and out back into the space of the ambulatory on the ground floor and then up into the gallery above.

Steven: But the real gem in this Church can be seen on the east end. Let's walk over there. The eastern end of San Vitale is completely covered in dense mosaic.

Beth: These tiny pieces of glass and glass sandwiching gold that reflect the light.

Steven: We're walking up towards the apse now, the semicircular space. There are three large windows. And just about that, a large apse mosaic.

Beth: And in the center, we see Christ dressed royally in purple sitting on an orb, the orb of the Earth, of the universe. Below flow the four rivers of paradise. And on either side of him, an angel.

Steven: Christ is holding the book of the apocalypse with the seven seals visible. And in his right hand, he's handing a crown to San Vitalis, who was adopted as the primary martyr of this city.

Beth: And on the other side, we see Ecclesius, who founded and sponsored the building of this church. And we see him handing the church to the angel beside Christ. Every surface here in the apse is covered with imagery, with figures, with decorative patterning.

Steven: The only surfaces that really are stone are of a very decorative marble, cut to pair and create wonderful abstract designs. It is this lush, glorious space here in this city that's distant, perhaps, from the capital of the empire, but that speaks to its importance.

Beth: Right above the altar, we see an image of the Lamb of God. And the Lamb of God refers to Christ. He's wearing a halo, this idea of Christ as the sacrificial lamb, sacrificed for the redemption of mankind.

Steven: The lamb is surrounded by a wreath of victory, in this case, the idea of the triumph of Christianity itself. And that wreath is held in place by four angels who stand on globes that refer to the globe upon which Christ in the apse sits.

Beth: And then we see Christ again, but this time bearded, older, in the archway at the beginning of the chancel.

Steven: Right. The triumphal arch has Christ in the center. It's really a kind of bust-length portrait. And his body is surrounded by a mandorla, kind of rainbow-colored halo. And then, moving down the arch on either side are 14 figures, including the apostles.

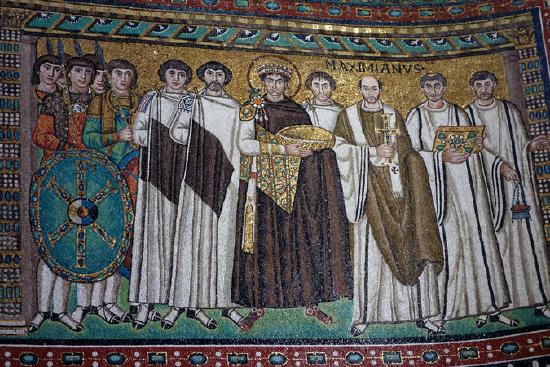

Steven: The two most important mosaics in San Vitale flank the apse.

Beth: And those show the emperor Justinian and his empress Theodora. Now, Justinian and Theodora never actually came to Ravenna.

Steven: And they're in the mosaics, we think, to reassert their control over the city.

Beth: For much of the 400s, Ravenna was under the control of a Goth, Theodoric, and Theodoric was an Arian, that is, he didn't follow the orthodoxy, the orthodox doctrines of the church.

Steven: And basically, the Arians believed that Christ was the creation of God the Father and therefore was subordinate in the hierarchy of the Trinity.

Beth: Christ was a co-equal with God the Father the way he is in orthodox Christian belief. And so Justinian, the emperor in Constantinople in the early 500s, sends his general, Belisarius, to conquer Italy, to reconquer Ravenna, and reestablish orthodox Christian belief here in Ravenna.

Steven: And the Arian belief was suppressed. And so what we're seeing here is the reassertion of Eastern imperial control. That is, Justinian is in Constantinople in the east, and he is saying, I'm in charge even here in Ravenna, in Italy.

Beth: Spiritual power goes hand in hand with political power, with the power of the emperor.

Steven: We see Justinian in the center wearing purple, the color that is associated with the throne. And he's surrounded by his court. But there are also religious figures representing the church and there are soldiers, three centers of power-- the church, the emperor, and the military.

Beth: We can see that some of the figures are treated more individualistically than others. Justinian, Maximian are more individualized. And it's possible that people at the time would have looked up and recognized the other figures who are lost to us today. But the figures from the army are much more anonymous.

Steven: Justinian, the emperor, authority, is divine. You can see a halo around his head. And he holds a bowl associated with the Eucharist, which he is handing in the direction of Christ in the apse.

Beth: Right. This is a bowl that would have contained the bread for the sacrament of the Eucharist. He's in the center of the composition. He's frontal. But really, all of the figures in this mosaic are frontal.

Steven: They are schematic, abstracted. This is the Medieval. We've left the Classical tradition of naturalism behind.

Beth: And so if we look closely at the figures, we can see that there's no real concern for accurate proportions. Their feet don't really seem to carry the weight of their bodies. They seem to float in an eternal space and not in an earthly space. Next to Justinian, we see the bishop, Maximian, with his name above him, although that was added later. And beside him, other clergymen.

Steven: Maximian holds a beautiful jeweled cross. And he wears the same purple that the emperor wears, associating him with the power of the emperor in Constantinople.

Beth: The figures next to him hold a jeweled book of the Gospels. And the figure at the far right holds an incense burner. What we're seeing here is the emperor leading a procession for the enactment of the sacrament of the Eucharist.

Steven: And in fact, the Eucharist would have been performed in the sanctuary. The figures stand in front of a field of gold, which is very much a Byzantine tradition.

Beth: And when we say Byzantine, we're referring to the capital of the empire, which is Constantinople.

Steven: Which we now call Istanbul. You'll notice that the tesserae, that is, these small pieces of colored glass, many of them with gold leaf that is actually fused almost like a sandwich in between two pieces of clear glass, are set into the wall at angles so that the light reflects off them in a way that is complicated and beautiful and creates a sense of the liveliness of the surface. And that would have been especially true when it was illuminated by candles and by lanterns. Let's walk around to the other side and take a look at the panel devoted to Theodora, Justinian's wife (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). To the right of the apse windows, we see the panel of Theodora, the empress. And it mirrors the panel with Justinian.

Beth: So we have an idea that Theodora, Justinian's empress, ruled as co-equal to Justinian, that she was a very powerful woman, even though she was reputedly of lower class, that she was an entertainer apparently.

Steven: There are some colorful descriptions of her past. She's wearing incredibly elaborate clothing and jewelry with rubies, with emeralds, with sapphires, and very large pearls. And in back of her head, just like Justinian, is a halo, which speaks not to her own divinity, but to the divine origin of her authority.

Beth: Like Justinian, who's carrying a bowl that held the bread for the Eucharist, Theodora is carrying the chalice for the wine for the Eucharist. And like Justinian, too, she's surrounded by attendants that symbolize the imperial court. A curtain is raised as though she is about to take part in a ceremony related to the Eucharist.

Steven: I'm really taken by the elaborate Byzantine costume.

Beth: Well, there's a sense of trying to bring the richness of the imperial court in Constantinople here to Ravenna.

The lives of Christ and the Virgin in Byzantine art

by Dr. Evan Freeman

The Byzantine Empire spanned more than a millennium and penetrated geographic regions far from the capital of Constantinople. As a result, Byzantine art includes works created from the fourth century to the fifteenth century and from such diverse regions as Greece, the Italian peninsula, the eastern edge of the Slavic world, the Middle East, and North Africa. So what is Byzantine art and what do we mean when we use this term?

Events from the lives of Jesus Christ and his mother, the Virgin Mary, were among the most frequently depicted subjects in Byzantine art. Many of these events were recorded in the four Gospels in the Christian Bible, but others were also inspired by non-biblical texts, such as the “Protoevangelion of James,” which were nevertheless read by the Byzantines. The Byzantines commemorated these events as church feasts according to the liturgical calendar each year (as does the Eastern Orthodox Church today, which is heir to Byzantium’s religious tradition).

Depictions of these events appeared in a wide range of media, on different scales, and in public and private settings. It would be inaccurate to imply that these scenes were always the same; they varied depending on the circumstances of their production as well as the periods in which they were made. Acknowledging the risk of oversimplifying an artistic tradition that endured for more than a millennium, this essay nevertheless seeks to introduce the stories and common features in Byzantine depictions of the lives of Christ and the Virgin.

This same imagery was used in Western European Christendom, usually later; there are many examples in Renaissance and Baroque art, for example. Most of the examples included here were created after the end of Iconoclasm.

Commonly depicted subjects in Byzantine art

The Birth of the Virgin

Drawn from non-biblical accounts such as the “Protoevangelion of James,” the Birth of the Virgin is commemorated as a Church feast on September 8. Anna, the Virgin’s mother, lies on a bed. Midwives bathe the newborn Mary. Other women bustle about, attending to Anna. Joachim, the Virgin’s father, sometimes appears as well. At Studenica Monastery in Serbia, Joachim stands beside the Virgin as she lies in a cradle after her bath in the lower right. (view annotated image)

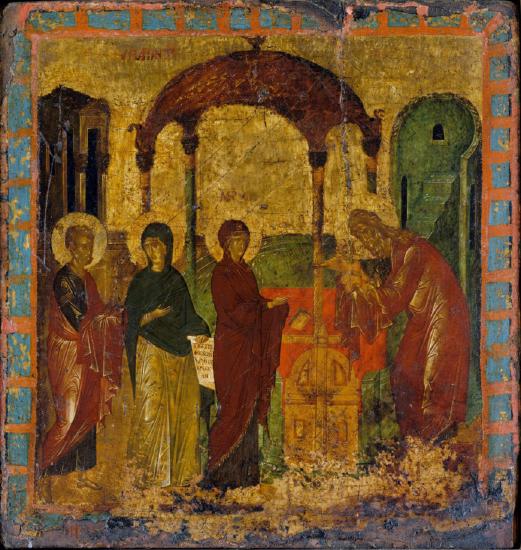

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple is based on non-biblical texts and is commemorated on November 21. The Virgin Mary is a child. She processes with her parents, Joachim and Anna, along with several candle-bearing maidens, toward the Jewish temple. Joachim and Anna offer the Virgin to God and the priest Zacharias receives her into the temple. As the narrative continues, Mary dwells within the temple, where an angel feeds her bread. The earliest examples of this image date to the tenth century. The hymnography for the feast emphasizes that the Virgin herself became a temple by allowing God to dwell in her when she conceived Christ. At the Chora Monastery, the procession to the temple takes a circular form to accommodate the vault where it appears. (view annotated image)

The Annunciation

The Annunciation (Greek: Evangelismos) is recorded in Luke 1:26–38 and commemorated on March 25. Simple compositions, such as the mosaic found at Daphni, show the archangel Gabriel approaching the Virgin Mary to announce that the Holy Spirit will come upon her and that she will conceive the Son of God, Jesus. Other images show the Spirit descending as a dove on a ray of light. Artists sometimes include additional details from a non-biblical text known as the “Protoevangelion of James.” The Virgin may hold scarlet thread to weave a veil for the temple or appear near a well where she is drawing water when the angel approaches.

The Nativity of Christ

The Nativity of Christ depicts the birth of Jesus. It is drawn primarily from Matthew 1:18–2:12 and Luke 2:1–20 and is commemorated on December 25. The newborn Christ appears in a manger (a feeding trough for animals) near an ox and ass. The Virgin sits or reclines near Christ, but Joseph is usually relegated to the periphery (appearing in the lower left corner in the miniature from the Menologion of Basil II) to minimize his role in the Christ’s birth (emphasizing Mary’s virginity). The narrative continues with one or two midwives bathing Christ. Angels announce the good news to shepherds. The star that guided the Magi from the east shines down on the Christ child. (view annotated image)

The Meeting of the Lord in the Temple

The Meeting of the Lord in the Temple (Greek: Hypapantē) is described in Luke 2:22–38 and commemorated on February 2. Mary and Joseph enter the Jewish temple to sacrifice two birds and offer Jesus to the Lord, in accordance with the Jewish law. They encounter the prophet Simeon (shown taking the Christ child in his arms in this image from The Metropolitan Museum of Art) and the prophetess Anna, who identify Christ as the Messiah. The temple is often visualized as a Christian church, indicated by a Christian altar and other church furniture. (view annotated image)

The Baptism of Christ

The Baptism of Christ (sometimes called “Theophany” or “Epiphany”) is recounted in Matthew 3:13-17, Mark 1:9-11, and Luke 3:21-22, and is commemorated by the Eastern Orthodox Church on January 6. John the Baptist, or “Forerunner,” baptizes Christ in the Jordan River, while attending angels stand nearby. The Holy Spirit descends on Christ in the form of a dove, while the words of God the Father identifying Jesus as his Son are represented by a hand blessing from the heavens. An ax appears with a tree, referencing the Baptist’s ominous words, “Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire” (Matthew 3:10). Sometimes, as at Hosios Loukas Monastery, the Jordan River is personified as a human figure in the water, corresponding with its personification in the hymnography for the feast. A cross also appears in the water at Hosios Loukas as a reference to the cross and column at the pilgrimage site associated with this event in Palestine, as described by a sixth-century pilgrim named Theodosius. (view annotated image)

The Transfiguration

The Transfiguration is described in Matthew 17:1-13, Mark 9:2-8, and Luke 9:28–36 and is commemorated on August 6. Jesus ascends a mountain (which tradition identifies as Mount Tabor) with Peter, James, and John (three of his disciples) and is transformed so that he shines with divine light. This light often appears as rays and a mandorla (an almond- or circle-shaped halo of light), as seen in the mosaic icon at the Louvre. Moses and Elijah—two figures representing the law and the prophets from the Hebrew Bible—appear on either side of Christ. Early examples of this motif are found at the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and Sant’Apollinare in Classe. (view annotated image)

The Passion

The Passion (“suffering”) refers to Christ’s sacrificial death on the cross and the period leading up to it. It is commemorated annually during Holy Week, whose dates vary from year to year based on the lunar cycle.

The Raising of Lazarus

The Raising of Lazarus (a friend of Christ’s) from the dead is recorded in John 11:38-44. The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates this miracle of Christ on the Saturday before Palm Sunday. Christ, trailed by the Apostles, calls forth the shrouded Lazarus from the tomb, as seen in the templon beam fragment in Athens. Mary and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, kneel at Christ’s feet. Additional figures open the tomb and free Lazarus from his grave clothes. One bystander usually holds his nose because of the stink of Lazarus’s decomposing body. (view annotated image)

The Entry into Jerusalem

The Entry into Jerusalem is recounted in Matthew 21:1-11, Mark 11:1-10, Luke 19:29-40, and John 12:12-19 and is commemorated on Palm Sunday, the Sunday before Pascha (Easter). Jesus rides into the city of Jerusalem on a donkey. A crowd hails him, throwing cloaks and palms on the road before him. Children often climb among the palm trees, as in the Berlin ivory. (view annotated image)

The Last Supper

The Last Supper, “Mystical Supper,” or just “Supper” (Greek: Deipnos), represents the meal that Christ shared with his disciplines before his crucifixion, which is recorded in Matthew 26:20-29, Mark 14:17-25, Luke 22:14-23, and I Corinthians 11:23-26, and is commemorated on Holy Thursday (known as “Maundy Thursday” in the Latin church). Judas reaches to dip his food in a bowl, which Christ identifies as a sign of betrayal. The table frequently takes the form of a late-antique, C-shaped “sigma” table as at the church of the Panagia Phorbiotissa in Asinou, Cyprus. Often, a large fish appears on the table, which may illustrate the ancient Christian use of the Greek word for “fish” (ichthys) as an acronym for “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.” The Last Supper is typically interpreted as the first celebration of the Eucharist. (view annotated image)

The Washing of the Feet

The Washing of the Feet occurred during the Last Supper, according to John 13:2-15. In the Gospel account, Peter resists letting Jesus wash his feet. But Christ explains: “If I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example” (John 13:14-15). The mosaic at Hosios Loukas Monastery shows Christ in the act of washing Peter’s feet. (view annotated image)

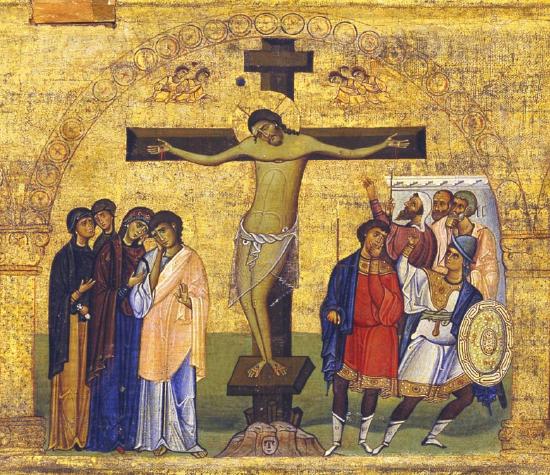

The Crucifixion

The Crucifixion depicts Christ’s death on the cross, described Matthew 27:32-56, Mark 15:21-41, Luke 23:26-49, John 19:16-37, and commemorated on Holy Friday (known as “Good Friday” in the west) during Holy Week. Simpler representations of the scene include the Virgin and John the Evangelist, illustrating John’s account. The sun and moon or angels appear in the sky above. More complex compositions, such as that found on a templon beam at Sinai, incorporate other women who followed Christ as well as Roman soldiers, such as Saint Longinus who converted to Christianity. John recounts how one of the soldiers pierced Christ with a spear, spilling blood and water from his side (John 19:34-35). The event unfolds at Golgotha, the “Place of the Skull,” outside of the city walls of Jerusalem (which sometimes appear in the background). Some depictions of this scene include a skull at the foot of the cross, which tradition identifies as the skull of Adam (the first man), reflecting the Christian belief that Christ is the “New Adam” as savior of humankind. (view annotated image)

The Deposition from the Cross

The Deposition from the Cross depicts Christ’s body being removed from the cross after his crucifixion. As at the church of Saint Panteleimon at Nerezi, the composition often includes the Virgin and John the Evangelist (who were present at Christ’s crucifixion), as well as Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, two followers of Jesus. It is based on Gospel accounts that describe Joseph of Arimathea burying Christ’s body in Joseph’s own tomb (Matthew 27:57-61, Mark 15:42-47, Luke 23:50-56, John 19:38-42). (view annotated image)

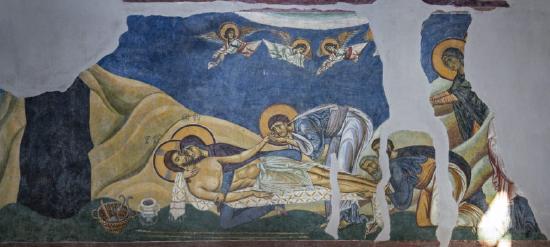

The Lamentation

The Lamentation, or Threnos, depicts Christ’s mother and other followers mourning over Christ’s dead body following the crucifixion. As at the church of Saint Panteleimon at Nerezi, the Lamentation often includes John the Evangelist (who was present at the Crucifixion), as well as Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, two followers of Jesus who helped remove his body from the cross and bury him. (view annotated image)

The Resurrection

The Resurrection of Christ from the dead occurred on the third day after his crucifixion according to New Testament accounts, and is celebrated each year on Pascha (Easter). The Gospels describe women who followed Jesus as the first witnesses to Christ’s resurrection: Matthew 28:1-10; Mark 16:1-8; Luke 23:55-24:12; John 20:1-18. Early Christian art depicts the myrrh-bearing women bringing spices to anoint Christ’s body but discovering that the tomb is empty. An angel tells them that Christ has risen from the dead. At Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, the empty tomb is envisioned as a rotunda, likely a reference to the Roman emperor Constantine’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre that marked the site of Christ’s resurrection in Jerusalem.

The Anastasis

The Anastasis (Greek for “resurrection”), also known as the “Harrowing of Hades” or “Harrowing of Hell,” became a standard resurrection composition from the eighth century onward. Based largely on non-biblical sources, the scene shows Christ descending into Hades (the underworld)—sometimes carrying his cross as an instrument of salvation—to raise the dead from their tombs. Locks and hinges lie broken underfoot as Christ tramples the broken gates of the underworld that once imprisoned the dead. In some images, Christ also tramples the personified figure of Hades, who represents death. At the Chora Monastery, Christ reaches with both hands to raise Adam and Eve (the first humans) from their tombs. Righteous figures from the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament—usually David, Solomon, and John the Baptist—stand nearby. The image corresponded with the chief hymn of Pascha (Easter): “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!” (view annotated image)

The Incredulity of Thomas

The Incredulity of Thomas appears in John 20:24-29, and is commemorated in the Eastern Orthodox Church the Sunday after Pascha (Easter). When some of the disciples claim to have encountered the risen Christ, the Apostle Thomas expresses doubt, stating: “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe” (John 20:25). A week later, Jesus appears and invites Thomas to touch his wounds: the moment depicted in this mosaic at Hosios Loukas Monastery. Thomas exclaims: “My Lord and my God!” (John 20:28). (view annotated image)

The Ascension

The Ascension of Christ into heaven, following his resurrection from the dead, is described in Luke 24:50-53 and Acts 1:9-12 and is commemorated on the Thursday that falls forty days after Pascha (Easter). The iconography derives from pre-Christian imperial apotheosis scenes (for example, on the Arch of Titus in Rome). Christ appears within a mandorla and is borne heavenward by angels, as seen in the miniature from the Getty Museum. The Virgin and Apostles stand on earth below. The ascension often appeared in church vaults, corresponding with the Byzantine interpretation of the church as a microcosm with the vaults representing the heavens. (view annotated image)

Pentecost

Pentecost (literally “the fiftieth day”) depicts the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles as described in Acts 2 and is commemorated fifty days after Pascha (Easter). The Holy Spirit takes the form of tongues of fire. Sometimes the Virgin appears with the Apostles, although she is not present in the biblical account. In Acts, the Holy Spirit inspires the Apostles to preach the crucified and risen Christ in different languages so that all can understand. In artistic representations of the event, figures representing different “tribes” and “tongues,” or a single figure personifying the entire “cosmos,” (seen in this miniature from the Getty) receive the Apostles’ words. Sometimes, the “prepared throne” (Hetoimasia) is included as the source from which the flames descend. (view annotated image)

The Dormition

The Dormition (Greek: Koimēsis, literally “falling asleep”) represents the death of the Virgin Mary, described in non-biblical texts and commemorated on August 15. The Virgin lies on her funeral bier surrounded by the Apostles. Christ stands behind the Virgin, receiving her soul, which takes the form of a swaddled infant. Later icons sometimes include additional details such as the Apostles miraculously borne to the scene on clouds and the gates of heaven opening to receive the Virgin. Tenth-century ivories from Constantinople like this one are among the earliest depictions of the Dormition. (view annotated image)

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Evan Freeman, "About the chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire," in Smarthistory, September 22, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Alicia Walker, "Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Early Byzantine period," in Smarthistory, July 30, 2021 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Diane Reilly, "The Vienna Genesis," in Smarthistory, April 18, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Ivory Panel with Archangel," in Smarthistory, October 20, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "The Emperor Triumphant (Barberini Ivory)," in Smarthistory, October 1, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Evan Freeman, "Icons, an introduction," in Smarthistory, December 3, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. William Allen, "Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)