14.3: Byzantium from the End of Iconoclasm to the Latin Conquest

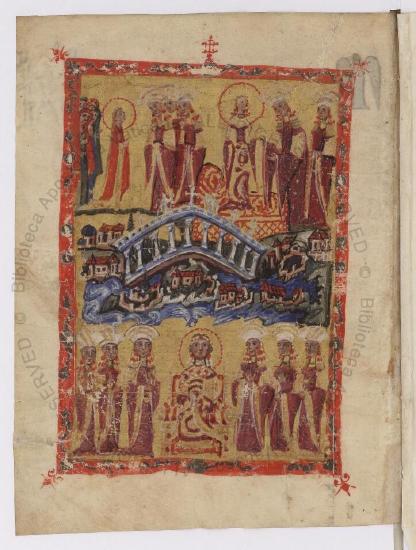

- Page ID

- 108743

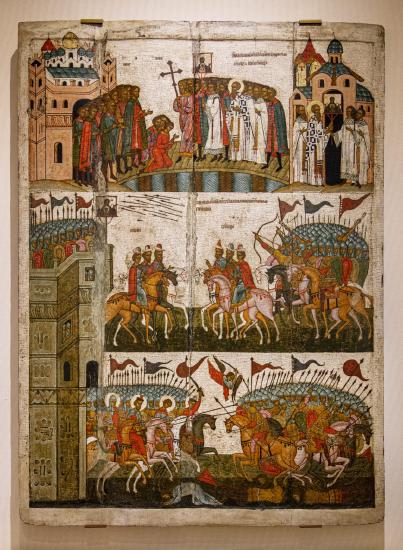

Byzantine Iconoclasm and the Triumph of Orthodoxy

by Dr. Evan Freeman

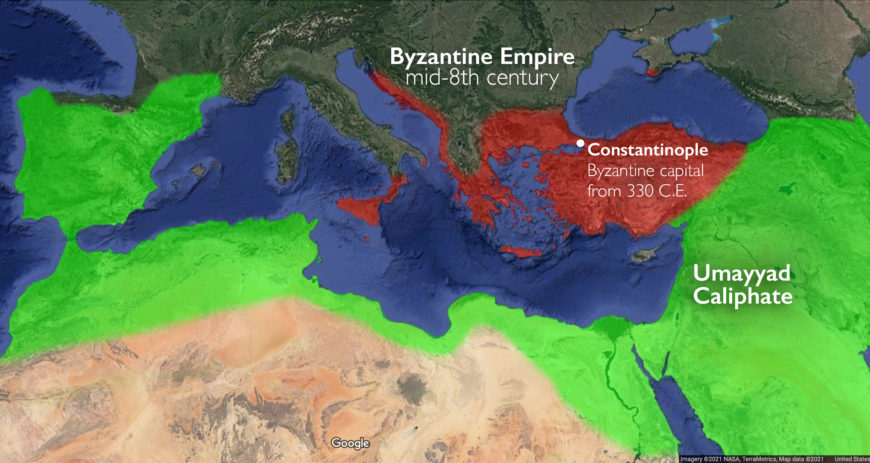

The “Iconoclastic Controversy” over religious images was a defining moment in the history of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. Centered in Byzantium’s capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) from the 700s–843, imperial and Church authorities debated whether religious images should be used in Christian worship or banned. Who were the players and what was this Controversy all about?

Key Terms

Icons (Greek for “images”) refers to the religious images of Byzantium, made from a variety of media, which depict holy figures and events.

Iconoclasm refers to any destruction of images, including the Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries, although the Byzantines themselves did not use this term.

Iconomachy (Greek for “image struggle”) was the term the Byzantines used to describe the Iconoclastic Controversy.

Iconoclasts (Greek for “breakers of images”) refers to those who opposed icons.

Iconophiles (Greek for “lovers of images”), also known as “iconodules” (Greek for “servants of images”), refers to those who supported the use of religious images.

What was the big deal?

Debating for over a century whether religious images should or should not be allowed may puzzle us today. But in Byzantium, religious images were bound up in religious belief and practice. In a society with no concept of separation of church and state, religious orthodoxy (right belief) was believed to impact not only the salvation of individual souls, but also the fate of the entire Empire. Viewed from this perspective, it is possible to understand how debates over images could entangle both Church leaders and emperors.

The arguments

The iconophiles and iconoclasts developed sophisticated theological and philosophical arguments to argue for and against religious images. Here is a quick summary of some of their main points:

The iconoclasts noted that the Bible often prohibited images, notably in the Second Commandment (one of the Ten Commandments appearing in the Hebrew Bible):

You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them….(Exodus 20:4–5, NRSV)

The iconophiles countered that while the Bible prohibited images in some passages, God also mandated the creation of images in other instances, for example God commanded that cherubim should adorn the Ark of the Covenant: “You shall make two cherubim of gold; you shall make them of hammered work, at the two ends of the mercy seat.” (Exodus 25:18, NRSV).

The iconoclasts argued that God was invisible and infinite, and therefore beyond human ability to depict in images. Since Jesus was both human and divine, the iconoclasts argued that artists could not depict him in images. The iconophiles agreed that God could not be represented in images but argued that when Jesus Christ, the Son of God, was born as a human being with a physical body, he allowed himself to be seen and depicted. Since some icons were believed to date to the time of Christ, icons were understood to offer a kind of proof that the Son of God entered the world as a human being, died on the cross, rose from the dead, and ascended into heaven—all for the salvation of humankind.

The iconoclasts also objected to practices of honoring icons with candles and incense, and by bowing before and kissing them, in which worshippers seemed to worship created matter (the icon itself) rather than the creator. But the iconophiles asserted that when Christians honored images of Christ and the saints like this, they did not worship the artwork as such, but honored the holy person represented in the image.

Timeline of events

Early centuries

Sporadic evidence of Christians creating religious images and honoring them with candles and garlands emerges from as early as the second century CE. Church leaders often condemned such images and devotional practices, which seemed too similar to the pagan religions that Christians rejected.

The seventh century

The Byzantine Empire faced invasions from Persians and Arabs in the seventh century, resulting in significant loss of territory. Trade decreased and the empire experienced an economic downturn. Byzantine anxieties over images likely emerge, at least in part, as a result of these devastating events (which may have been perceived as signs of God’s displeasure with icons).

Through the centuries, icons became increasingly widespread in Byzantium. By the late seventh century, the Church began to legislate on images. Church leaders at the Quinisext Council (also known as the Council of Trullo) held in Constantinople in 691–692 prohibited the depiction of crosses on floors where they could be walked on, which was understood as disrespectful. They also mandated that Christ be depicted as a human rather than symbolically as a lamb in order to affirm Christ’s incarnation and saving works. Around this same time, emperor Justinian II incorporated icons of Christ onto his coins. These events suggest the growing importance of religious images in the Byzantine Empire at this time.

The first phase of Iconoclasm: 720s–787

Historical texts suggest the struggle over images began in the 720s. According to traditional accounts, Iconoclasm was prompted by emperor Leo III removing an icon of Christ from the Chalke Gate of the imperial palace in Constantinople in 726 or 730, sparking a widespread destruction of images and a persecution of those who defended images. But more recently, scholars have noted a lack of evidence supporting this traditional narrative, and believe that iconophiles probably exaggerated the offenses of the iconoclasts for rhetorical effect after the Controversy.

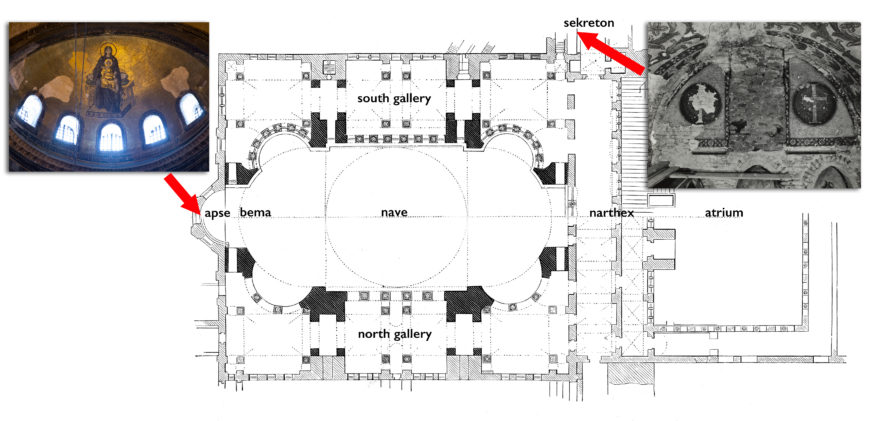

Historical evidence firmly identifies Leo’s son, emperor Constantine V, as an iconoclast. Constantine publicly argued against icons and convened a Church council that rejected religious images at the palace in the Constantinople suburb of Hieria in 754. Probably as a result of this council, iconoclasts replaced images of saints with crosses in the sekreton (audience hall) between the patriarchal palace and Constantinople’s great cathedral, Hagia Sophia, in the 760s (discussed further below).

787 Iconophile Council of Nicaea II

In 787, the empress Irene convened a pro-image Church council, which negated the Iconoclast council held in Hieria in 754 and affirmed the use of religious images. The council drew on the pro-image writings of a Syrian monk, Saint John of Damascus, who lived c. 675–749.

The second phase of Iconoclasm: 815–843

Emperor Leo V, who reigned from 813–820, banned images once again in 815, beginning what is often referred to as a second phase of Byzantine Iconoclasm. Leo V’s ban on images followed significant Byzantine military losses to the Bulgars in Macedonia and Thrace, which Leo may have viewed as a sign of God’s displeasure with icons. Theodore, abbot of the Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople, wrote in defense of icons during this time. Evidence suggests this second phase of Iconoclasm was more mild than the first.

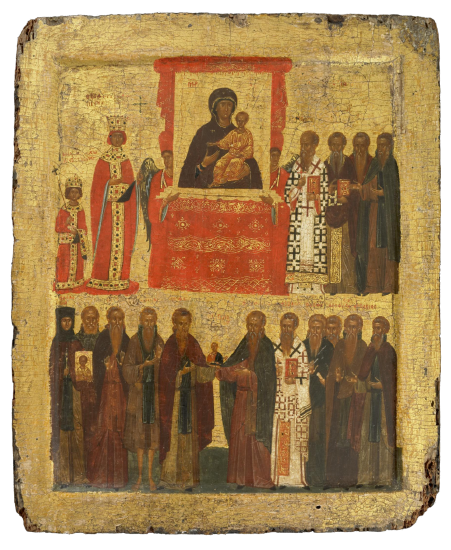

The Triumph of Orthodoxy

The iconoclastic emperor Theophilos died in 842. His son, Michael III, was too young to rule alone, so empress Theodora (Michael III’s mother), and the eunuch Theoktistos (an official), ruled as regents until Michael III came of age. Later sources describe Theodora as a secret iconophile during her husband’s iconoclastic reign, although there is a lack of evidence to support this. For reasons not entirely clear, Theodora and Theoktistos installed the iconophile patriarch Methodios I and once again affirmed religious images in 843, definitively ending Byzantine Iconoclasm.

Imperial and Church leaders marked this restoration of images with a triumphant procession through the city of Constantinople, culminating with a celebration of the Divine Liturgy in Hagia Sophia. The Church acclaimed the restoration of images as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy,” which continues to be commemorated annually on the first Sunday of Lent in the Eastern Orthodox Church to this day.

Iconoclasm and the Triumph of Orthodoxy in Byzantine Mosaics

The Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy was not merely an intellectual debate, but was also an inflection point in the history of Byzantine art itself. Let us consider the examples of three Byzantine churches, whose mosaics offer visual evidence of the Iconoclastic Controversy and subsequent Triumph of Orthodoxy: Hagia Eirene in Constantinople (Istanbul), the Dormition in Nicaea (İznik, Turkey), and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul).

Hagia Eirene in Constantinople

The emperor Justinian constructed the church of Hagia Eirene in Constantinople (Istanbul) in the sixth century, but the church’s dome was not well supported, and the building was badly damaged by an earthquake in 740. Emperor Constantine V, who reigned from 741–775, rebuilt Hagia Eirene in the mid to late 750s.

Constantine V—who, as an iconoclast, opposed pictorial depictions of Christ and the saints—is credited with decorating the apse of the church with a cross, which the iconoclasts found acceptable. The cross mosaic makes liberal use of costly materials, such as gold and silver. The skilled artists who created the mosaic bent the arms of the cross downward to compensate for the curve of the dome so that the crossarm would appear straight to viewers standing on the floor of the church.

Clearly, while the iconoclasts opposed certain types of religious imagery, they did not reject art entirely, and were sometimes important patrons of art and architecture, as was Constantine V. There is also evidence that emperor Theophilos—who reigned during the second phase of Iconoclasm—expanded and lavishly decorated the imperial palace and other spaces.

The church of the Dormition in Nicaea

Iconoclastic activity can be directly observed in the mosaics of the church of the Dormition (or Koimesis) at Nicaea (İznik, Turkey). Although the church does not survive today, photographs from 1912 clearly show seams, or sutures, where parts of the mosaics were removed and replaced during the Byzantine era.

Although the precise history of the mosaics at Nicaea is difficult to reconstruct, the 1912 photographs clearly indicate three distinct phases of creation and subsequent restorations during and after the Iconoclastic era.

Phase 1 (yellow) The original mosaics predate Iconoclasm and were probably created in the late seventh or early eighth century. They pictured the Virgin and Child standing on a jeweled footstool in the apse. An inscription refers to the church’s founder, whose name was Hyakinthos.

Phase 2 (red) Sometime during the Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries, the image of the Virgin and Child was removed and replaced with a plain cross like the one in Hagia Eirene in Constantinople, whose outlines can still be partially observed in the 1912 photograph.

Phase 3 (purple) Sometime after the Triumph of Orthodoxy in 843, the cross was replaced with another image of the Virgin and Child.

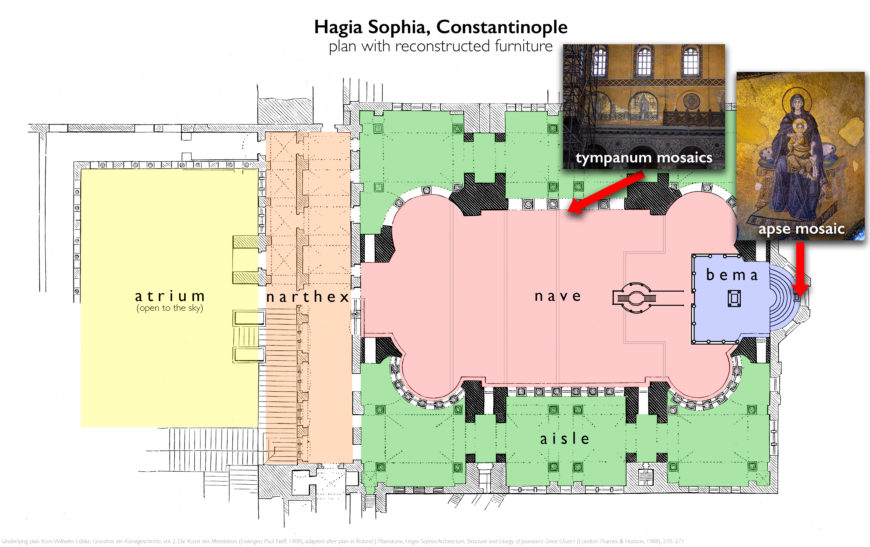

Hagia Sophia in Constantinople

Iconoclasm in the sekreton

The only surviving evidence of destruction of images in the Byzantine capital survives at Hagia Sophia, in audience halls (sekreta) that connected the southwestern corner of the church at the gallery level with the patriarchal palace. Primary sources speak of patriarch Niketas—the highest-ranking Church official in Constantinople—removing mosaics of Christ and the saints from the small sekreton sometime between 766–769.

And as at the church of the Dormition in Nicaea, scars are visible in the mosaics in the small sekreton. Roundels with crosses, which survive today, likely once contained portraits of saints, which patriarch Niketas is said to have removed. Beneath the roundels, the ghostly remnants of erased inscriptions indicate where the missing saints’ names once appeared.

Apse mosaic and the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Following the Triumph of Orthodoxy, the Byzantines installed a new mosaic of the Virgin and Child in the apse of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. The image was accompanied by an inscription (now partially destroyed), which framed the image as a response to Iconoclasm: “The images which the imposters [i.e. the iconoclasts] had cast down here pious emperors have again set up.” Yet unlike at Nicaea, there is no evidence of the apse’s previous decoration or of any interventions by iconoclasts. So while the inscription implies that iconoclasts removed a figural image from this position, this ninth-century Virgin and Child mosaic installed after the Triumph of Orthodoxy may be the first such figural image to occupy this position in Hagia Sophia.

In 867, patriarch Photios, the highest-ranking Church official in Constantinople, preached a homily in Hagia Sophia on the dedication of the new mosaic. Photios condemned the iconoclasts for “Stripping the Church, Christ’s bride, of her own ornaments [i.e. images], and wantonly inflicting bitter wounds on her, wherewith her face was scarred. . . .” He went on to speak of the restoration of images:

[The Church] now regains the ancient dignity of her comeliness. . . . If one called this day the beginning and day of Orthodoxy . . . one would not be far wrong. Photios, Homily 17, 3

The mosaic in Hagia Sophia and the homily by Photios both illustrate how the iconophiles—the victors of the Iconoclastic Controversy—framed their victory as a triumph of religious orthodoxy, perhaps exaggerating the offenses of the iconoclasts along the way for rhetorical effect.

Copying — spotlight: Virgin Hodegetria

by Dr. Asa Simon Mittman

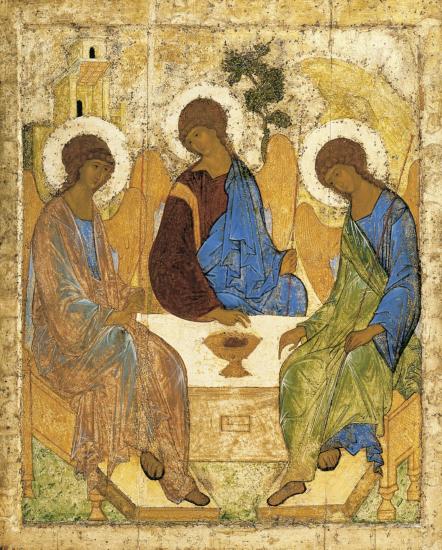

In the early fourth century, the Roman Emperor Constantine decriminalized Christianity and began funding churches and works of art. He also moved the capital of the Empire from Rome to Byzantium, a wealthy city in modern-day Turkey, which he then renamed Constantinople after himself (today we call this city Istanbul). While at the time, its inhabitants still called their empire Rome, we now refer to it as the Byzantine Empire, which lasted about a thousand years, ending in the 15th century, when the army of the powerful Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople. The most characteristic creation of the Byzantine period is the icon—an image of a holy figure or event from Christian tradition, often presented against a gold background and thereby separated from any worldly context.

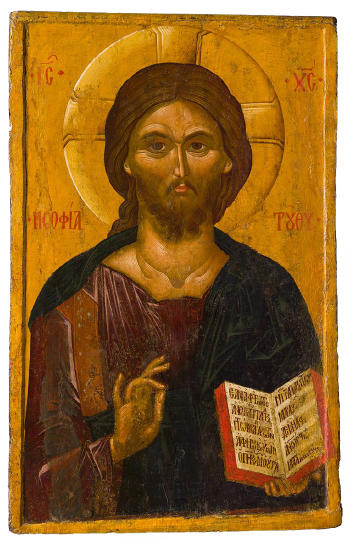

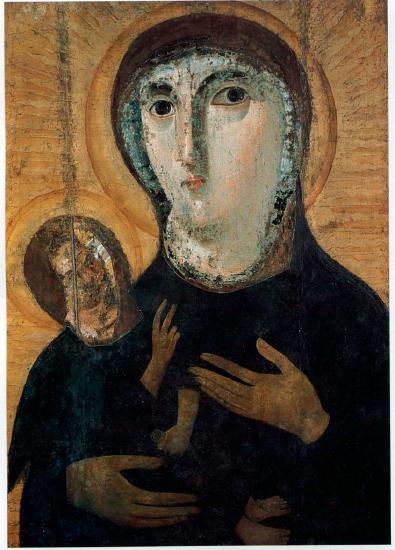

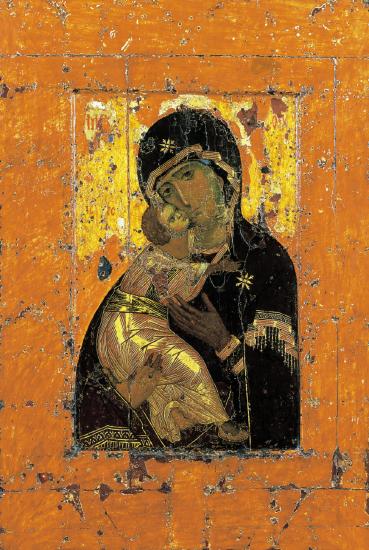

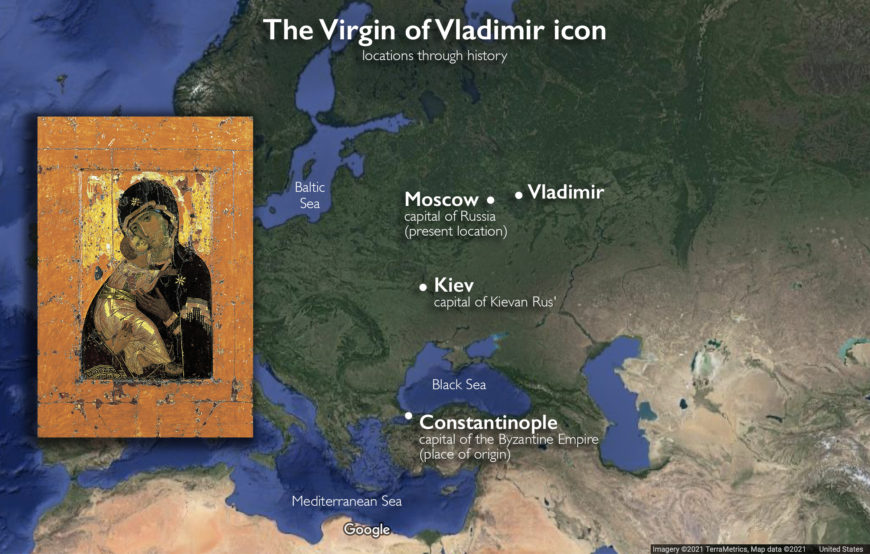

One of the most common subjects for such icons is the Virgin Hodegetria, literally “She Who Shows the Way” in Greek. These are images in which the Virgin Mary holds Jesus and gestures toward him, guiding the viewer to Jesus and therefore, according to Christian belief, to salvation. Because of its common appearance from Late Antiquity to the present, Hodegetria icons are useful examples of the remarkable continuity of copies of icons throughout time.

At a glance, Byzantine icons strike many viewers as repetitive, that is, as being more or less the same. Their similarity, though, is by careful design. Their makers sought to preserve information about the appearances of their subjects, and traditions of their representations, and thereby to produce images that were both accurate and magically or divinely powerful.

To be clear, the icons discussed here are a few examples out of thousands of this same subject, and there is no evidence that these particular images were directly copied from one another. Rather, they were part of a large network of icons, all based on related models.

Visual elements

One of the earliest known versions of the Virgin Hodegetria is now housed in Santa Francesca Romana, in Rome, Italy (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). This work has been altered more than once, and has been extensively restored, so its details do not accurately reflect its original state, but do record some of the ways it changed over the centuries. The two faces are the oldest parts, painted in encaustic (pigment suspended in wax) on canvas. Sometime in the Middle Ages, these heads were cut out and inserted into a new painting, which is why the faces seem out of place. They are different in technique (the medieval portion of the icon is tempera on wooden panel) but also in color and scale. Jesus’s face seems far too small for his head. Mary’s face seems too large for hers, and is much paler than her hands. It is also likely set at the wrong angle; her neck meets her body at an angle, suggesting that in the original work, her head was inclined toward Jesus.

But despite these later interventions, what we see in this image is quite typical of Hodegetria icons: a bust-length image of Mary, holding Jesus with one hand and gesturing toward him with the other. She wears a dark blue robe, as does Jesus. He holds a scroll in one hand and raises the other toward Mary in a two-fingered gesture of blessing. Her face is quite pale and, surrounded by her dark clothing and the gold background, draws our eyes. In this case, she looks out at us, while he looks up at her. Her eyes are dramatically enlarged, and their irises are very dark against their whites, so that they become the focal point for the work. We are compelled to make eye contact with Mary, as she then encourages us to look to Jesus. Behind them, on the restored golden background, we see two haloes, with Mary’s radiating waves of light that again guide our eyes back to her face.

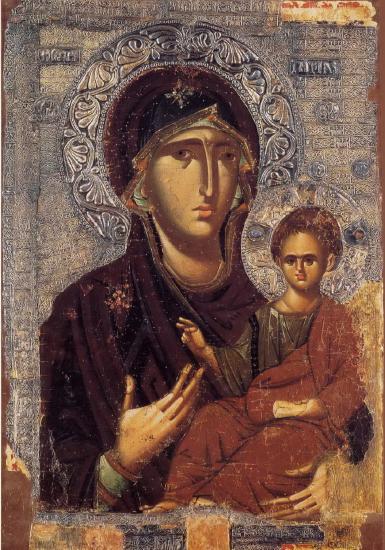

Almost a millennium later, little has changed. An icon of the Hodegetria from the thirteenth century preserves many of the features of the earlier icon. Again, there were changes made to the icon over time, including the addition of embossed silver, covering the original gold background, which now shows through at the edges where the silver has been lost.

The changes made to these icons over time indicates both their usage, which results in wear and tear, and their importance—damaged works can always be replaced rather than repaired. The whole image has been reversed, so that Jesus is now to Mary’s left, which will remain more common. Some features are strikingly similar. In addition to their basic gestures and poses, Mary’s very long nose, sharply cut brows, and very small mouth are quite similar. Again, she looks out at us, though her eyes are no longer so dramatically oversized. Jesus still holds a scroll in his left hand and raises his right in blessing. Jesus’ attention, though, has been shifted quite significantly from Mary to us. He looks out as us, and his hand, with the same gesture as in the earlier icon, is now turned toward us. The impact for a devout Byzantine Christian would be quite different, now that he or she is the object of Jesus’s blessing.

There is something peculiar about the size and shape of Jesus’ head. It may be intended to suggest that, though he is here a baby, he already bore adult (and divine) wisdom. On the other hand, it may be an echo of the strange medieval reconstruction of the earlier icon, where the earlier, smaller face of Jesus was set into the larger head of the later work.

Moving forward another three hundred years to a sixteenth-century Russian Hodegetria icon, we find that much is again copied from earlier models. The two figures are posed as before, Mary in her blue robes against a backdrop of gold. Mary’s features are quite similar to the earlier works—her long, narrow nose, her sharp brows, and her small mouth. And again, Jesus bears the curiously enlarged forehead. He is yet smaller, though, and more doll-like in her arms, and his proportions are less child-like. He is proportionally taller and thinner, more like an adult. This effect furthers the implications that he has adult wisdom. The figures also seem more cheerful—their lips curve up ever so slightly at the corners.

The Byzantine icon tradition carries on in the present, especially in Greece, Russia, and eastern Europe, though it is present all throughout the world. Contemporary London-based icon painter Christabel Helena Anderson created her The Theotokos of the Don in 2011. Its connection to the 1500-year tradition that preceded its creation is clear. Again, Mary bears her long nose and sharp brows and Jesus’s head is oversized and bulbous. The sixteenth-century icon—or any of the many like it—seems to have been a direct inspiration for Anderson, as the robes are strikingly similar. Anderson has, however, made her own alterations. Most importantly, she has made the scene significantly more tender, with the child pressing his cheek against his mother’s. Jesus looks up at Mary, and his two-fingered gesture of blessing is turned toward her, rather than toward us. Instead of making eye contact with us, Mary looks off into the middle-distance, her gaze seemingly unfixed, and her expression ambiguous. Is she perhaps contemplating the sorrowful fate of her baby? In a sense, this is not a Hodegetria, properly speaking, because Mary does not “show us the way” by guiding the viewer toward Jesus. The pair is more self-contained, sharing what seems to be a private emotional moment. The work is clearly and deeply rooted in the very long icon-painting tradition, but like many icon painters before her, Anderson finds a way to create something new out of a very well-worn formula.

Each artist who turns to this subject has a challenge: how does one preserve the perceived accuracy and authority of the image, while creating a work that is new, fresh, and effective? The goal is not “originality,” since a genuinely original work would break the connection with the works of the past from which the new icons draw their power. But a work of simple, rote copying is likely to be less effective than one that finds a way to bring nuance to an old theme.

Cultural context: Byzantine Icons

Hodegetria icons were considered particularly important and authoritative, since it was believed that the first version was painted by St. Luke, author of one of the four Gospels—the core texts of Christianity. This version was therefore considered accurate and authoritative; artists strove—and still strive—to copy it as exactly as possible, in order to preserve its record of what they believe to have been an actual, historical moment when Luke painted Mary and Jesus from life. There is debate over what happened to this first image. Some believe it was destroyed when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453. Others believe it was smuggled out of Constantinople, and survives in Western Europe, though this camp has not reached consensus on which of several possible icons is the one painted by Luke. Most art historians, though, believe that the form of the Hodegetria developed in the Early Byzantine period, perhaps in the fifth or sixth century.

Icons were quite controversial in the Early Byzantine period. At the time, Christianity was still working to demonstrate its difference from Roman polytheism (the worship of many gods, in this case Jupiter, Juno, Mars, Venus, and the rest of the Roman pantheon of deities). One of the main differences that early Christians and their Byzantine successors sought to emphasize was their rejection of polytheistic worship of idols, that is, of statues believed to represent and house gods. Some Christians, following the Second Commandment, which prohibits idol worship, saw any images as problematic, but many others embraced images. The ways that icons were often used by Byzantine Christians did not help their critics to feel any more at ease. Numerous records survive that indicate that many Christians were treating the physical objects (as well as the figures they represented) as powerful, magical, or divine. Icons were dipped into poisoned wells to purify them. Sick people would shave off bits of icons to make medicinal drinks. Icons were carried as protective talismans before armies heading into battle. All of these practices indicate that, whatever highly educated Christian writers thought about the difference between worship of idols and veneration (honoring) of icons, many people clearly confused the two, and treated Christian icons in much the same ways their families had treated polytheistic idols, only a few generations earlier.

When the Byzantine Empire was threatened by the spread of new powers and religions, particularly by the rise of Islam and the attendant Muslim conquests of territory, images were placed at the center of internal debates. Tensions between iconophiles (those who favored the use of icons), and iconoclasts (those who opposed icons) led to the Iconoclastic Controversy (the first phase of Iconoclasm, 720s–787 and the second phase of Iconoclasm, 815–843). This was probably the longest sustained debate on the use of art in the world’s history. The extent of the destruction of images and persecution of iconophiles is a subject of current debate among scholars, and it is worth bearing in mind that the early sources we have describing these events were written by iconophiles after the controversy ended. Whatever the cause, though, only a handful of icons survive from before the Controversy. The debate centered on the use of the images. In particular, did the veneration of icons violate the Second Commandment?

You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing love to a thousand of those who love me and keep my commandments.Exodus 20:5-6

To make their case, iconoclasts simply pointed to this fairly strict regulation of images, though the Bible contains other passages that provide direct instruction on the creation of three-dimensional images, so this case is not as simple as it is often presented as being. The iconophiles, in contrast, made intricate arguments in favor of the use and veneration of images. They held that Jesus, whom they considered to be the son of God and therefore God, himself, became an incarnate human being and thereby allowed himself to be seen. If, the argument ran, God allowed himself to be seen in physical form, making images of that form could be seen as following this divine example. Those in favor of images ultimately triumphed, not only because of their theological arguments, but undoubtedly also because, on the whole, people love images. The Byzantines resumed creating and venerating icons in 843 CE, and Byzantine Christians (modern day Orthodox Christians) have been copying and reinterpreting their earliest surviving models, ever since.

The vita icon in the medieval era

by Dr. Paroma Chatterjee

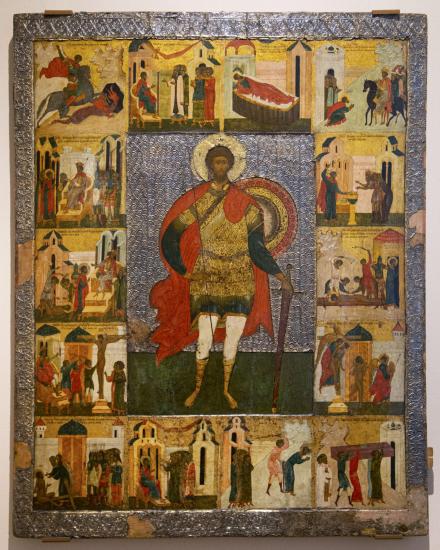

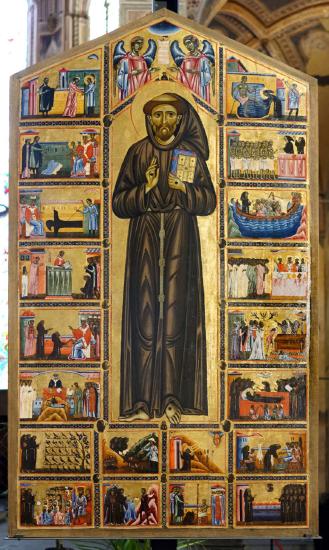

The “vita” icon is literally the image of a life. Its usual format consists of the magnified central portrait of a saint surrounded by those episodes in his/her biography that made him/her a saint. In these vignettes, the saint appears in a smaller and relatively more active stance as s/he goes about the business of sanctity by performing miracles, praying, and sometimes, even being martyred.

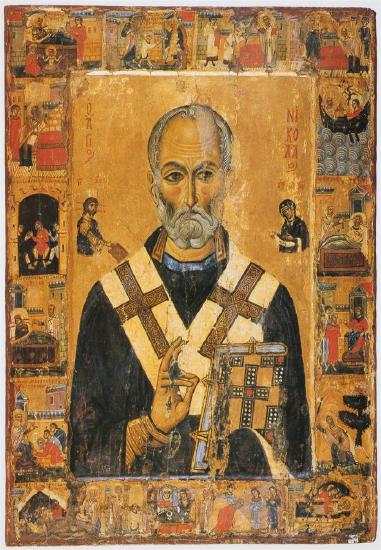

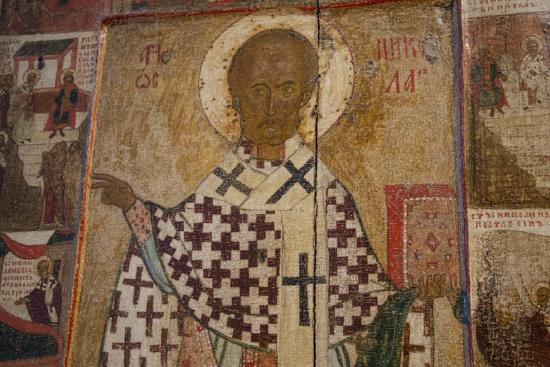

A vita icon of St. Nicholas

The “vita” icon of St. Nicholas, currently located in the Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt, is a perfect example. The bust of the saint looms large at the center whereas the smaller, full-figured, mobile version of Nicholas features on, and as, a frame on all four sides.

One may begin to read this frame from the top left hand corner (although we have no evidence that viewers did so) where Nicholas appears as an infant who miraculously stood erect in his bath. As we proceed horizontally, we see Nicholas’ transformation to a child, an adolescent, and finally, at the top right hand corner, an adult.

But after that, one might be at a loss as to know where to direct one’s gaze, for nowhere are we given any specific visual or textual directions (although in some examples of the “vita” icon, one may detect, upon trying, a logical narrative design to the episodes). We could skip to the left-hand side of the panel and continue vertically all the way down, or we could scan the rectangular panels on the left and right alternately, criss-crossing the still, hieratic, central bust as we do so. Regardless of the visual path we choose to follow, we catch glimpses of various moments in Nicholas’ life.

Viewers may even have focused on a small selection of scenes, or the bust alone, depending on lighting conditions and how close they might have been to the icon. In the flicker of candle light, it is more than probable that a number of details on the frames might have been lost. However, if the “vita” icon were displayed as a proskynetarion icon (an image placed on a stand, usually at eye level, for veneration on a feast day), then it probably would have been visible for contemplation in its entirety at various moments of the day. This example of the icon of St. Nicholas suggests a flexibility of viewership enabled by the “vita” format in juxtaposing the monumental and miniature versions of a saint in a non-linear orientation.

Origins of the vita icon

The precise date of the origin of the “vita” icon format is debated, with some arguing for the 10th century C.E. and others positing a slightly or much later period ranging from the 11th to the 13th centuries. The general characteristics of the format in the Byzantine Empire are: size (ranging from 70 cm to 2 m in height), and the remarkable consistency of standardized scenes that appear on the frame from icon to icon; in other words, surviving “vita” icons of St. Nicholas often display similar scenes. The frame is an intriguing phenomenon in itself since from the 11th-century onward we find the addition of precious revetments (thin sheets) of gold, silver, and other metals, which often feature donor portraits and inscriptions.

Image and text

“Vita” icons usually incorporate texts identifying the saint and the episodes from his/her life. While we might expect the narrative scenes in the frames of “vita” icons to parallel written accounts of saints’ lives, or “hagiographies,” which were widely circulated in the medieval era, scholars have remarked on the apparent independence of “vita” icons from the standard textual versions of the lives of the saints depicted. By the 11th century in the Byzantine Empire, saints’ lives had been compiled into a more or less definitive version by Symeon Metaphrastes known as the Metaphrastean Menologion; yet, the “vita” icons from the 13th century do not reflect this book so much as older hagiographies. Some have argued that this was probably because the 13th-century exemplars are copies of even older “vita” icons which, in turn, relied on the earlier hagiographical texts. While this may have been the case from the point of view of the creators and patrons of the icons, from the perspective of the viewer these panels may be read as visual statements in their own right with the inscriptions permitting the identification of scenes, not necessarily intended to evoke specific passages in written hagiographies.

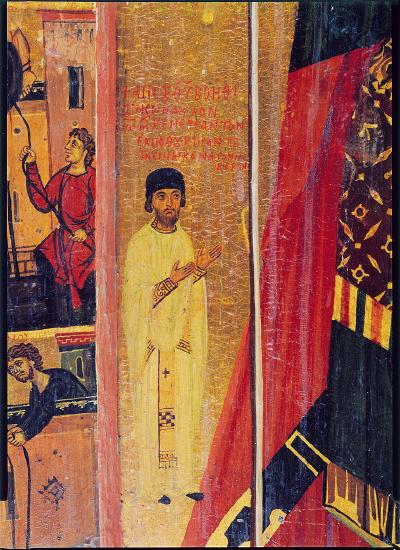

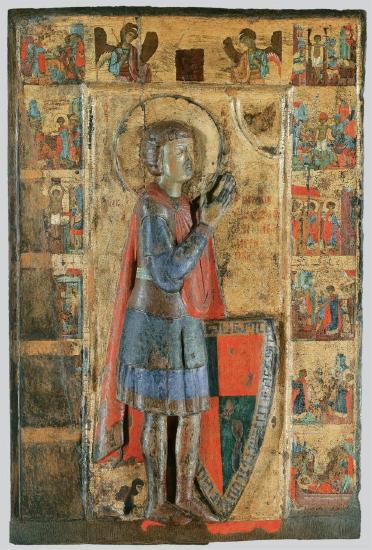

The mobility of vita icons

Since a significant number of Byzantine “vita” icons are preserved in the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, Egypt (view location on map), it is possible that some might have been gifted or donated to the Monastery by pilgrims. One of the 13th-century “vita” icons of St. George, for example, depicts a donor figure sandwiched between the towering, imposing figure of the warrior-saint and the frame. Clad in white in stark contrast to the broad swathes of red and black characterizing George, this figure is identified as John the Iberian (“Iberian” here is a reference to medieval Georgia on the eastern shore of the Black Sea) who was both monk and priest. Alternatively, some of the icons might have been made at the Monastery of St. Catherine itself.

More interesting than these questions of origins, is the fact that the “vita” icon format gained popularity across Europe within a relatively short period. This may have occurred because of its distinctiveness and clarity in conveying information about saints as individuals, as well as its ability to make a vivid visual statement about sanctity writ large. Examples are known in Italy, Cyprus, and Russia, among other places.

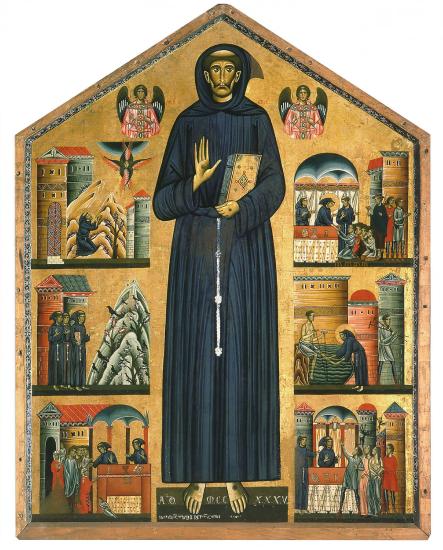

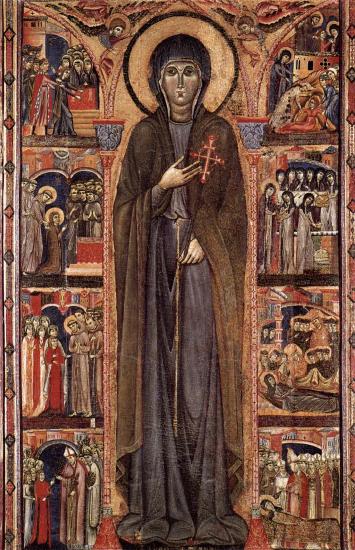

Vita icons, east and west

“Vita” icons were most strikingly used in the service of one of the most radical saintly personalities of the medieval west: Francis of Assisi, whose life and many posthumous miracles were included in the format. As the first person to have been recognized officially as a genuine stigmatic (St. Francis was blessed with the wounds of Christ) by the Catholic Church, St. Francis revolutionized ideas of the human body (as an image of the divine), the natural world (Francis preached to birds and other animals), and property (Francis advocated the renunciation of worldly possessions), although a number of Franciscan ideals stemmed from existing strands of ascetic and monastic thought and practice.

One major difference between the Byzantine and Western “vita” icons is that the format was almost exclusively used in the east for well-established, long-deceased saints (e.g. Nicholas and George) and in the west for recently minted saints (e.g. Francis), and initially for those associated with the Franciscan Order such as St. Clare of Assisi and St. Margaret of Cortona.

Some of the Franciscan “vita” icons were also used as altarpieces (a work of art set above and behind an altar)—a category of object that was never used in the medieval Orthodox church, but which furnished a focus of devotion and a high degree of visual elaboration in the Roman Catholic churches of western Europe.

In Slavic Rus', too, by the fourteenth century we find the phenomenon of recent saints such as Boris and Gleb, sons of prince Vladimir the Great of Kievan Rus’, portrayed in the “vita” format, along with icons dedicated to far more traditional figures such as Elijah and St. Nicholas.

Variations

Although “vita” icons most commonly appear in tempera on wood panels, we sometimes find the “vita” format deployed in intriguing variations in media, such as in frescoes or textiles. In some instances, the confection plays on the deliberate contrast of media, displaying the central figure in relief and the images on the frame as panel paintings, as seen with a thirteenth-century icon of St. George in Athens.

In other cases the “vita” format seeks to recreate not just the saint per se, but a specific local image of the saint which was probably known and venerated previously. Such is the case of the church of St. Nicholas tis Steges in Kakopetria, Cyprus in which a life-sized frescoed image of St. Nicholas was likely reproduced in the large “vita” icon dedicated to the same saint and formerly located in that very church. Interestingly, this vita icon of St. Nicholas portrays Latin, and not Byzantine, donors on its frame, thus attesting to the general appeal of the visual format across faiths and ethnicities.

A work in progress: Middle Byzantine mosaics in Hagia Sophia

by Dr. Evan Freeman

Who was the artwork’s patron? What were the artwork’s original meanings and functions? When art historians study a work of art, they ask questions about the artwork’s initial creation. But often, works of art and architecture change over time, challenging us to take a longer view of an artwork’s history and position within social networks, something anthropologist Arjun Appadurai referred to as the “social life” of a thing. [1]

This is the case with the Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia—the main cathedral in Constantinople (modern Istanbul)—which the Byzantines often referred to as the “Great Church.” Built by emperor Justinian during the brief period of 532–537, Hagia Sophia was at first primarily decorated with crosses and non-figural motifs. But in subsequent centuries—and particularly following the a ban on religious images (icons) during the Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries—several figural mosaics were added to the walls of Hagia Sophia, which dramatically changed the appearance of Justinian’s Great Church. These mosaics illustrate the ways Hagia Sophia became entangled in and responded to theological controversies, imperial donations, and even marriages.

Holy figures

Apse mosaic: Virgin and Child

The first major mosaic added to Hagia Sophia following the 843 end of Iconoclasm depicted the Virgin Mary and Christ Child in the apse, the semidome above the altar at the eastern end of the church. It was accompanied by an inscription that alluded to Iconoclasm: “The images which the imposters [i.e. the iconoclasts] had cast down here pious emperors have again set up.” The mosaic was probably completed around 867, when patriarch Photios, the leader of the Church in Constantinople, preached a sermon that also interpreted this image in terms of the end of Iconoclasm. The location of this Virgin and Child mosaic—which visualized Christ’s incarnation (becoming flesh and blood)—was also significant since the Byzantines believed that the Eucharistic bread and wine similarly became Christ’s flesh and blood on the altar below.

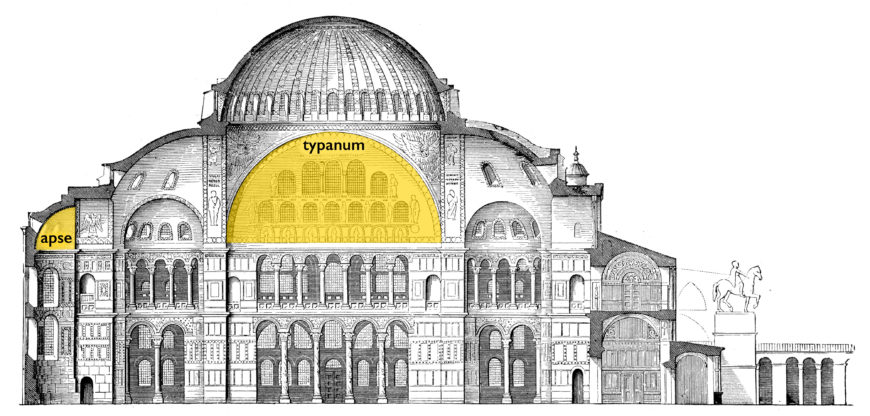

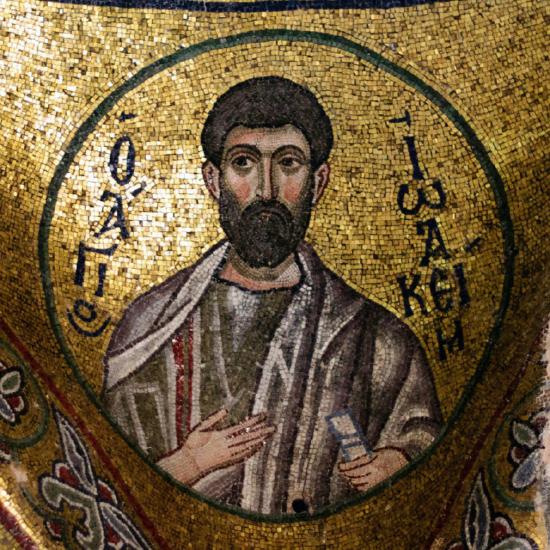

Tympana mosaics

Not long after the apse mosaic was installed, additional mosaics were added high on Hagia Sophia’s north and south walls, in the tympana beneath the central dome, toward the end of the ninth century.

These depicted rows of holy figures—Church fathers on the bottom, prophets in the middle, and probably angels above—though only a few of these mosaics survive today. Strikingly, recent patriarchs such as Ignatius the Younger (who died in 877) are pictured among Church fathers in the tympana, likely because of their defense of images during Iconoclasm, as well as their association with Hagia Sophia.

Emperors and ceremony

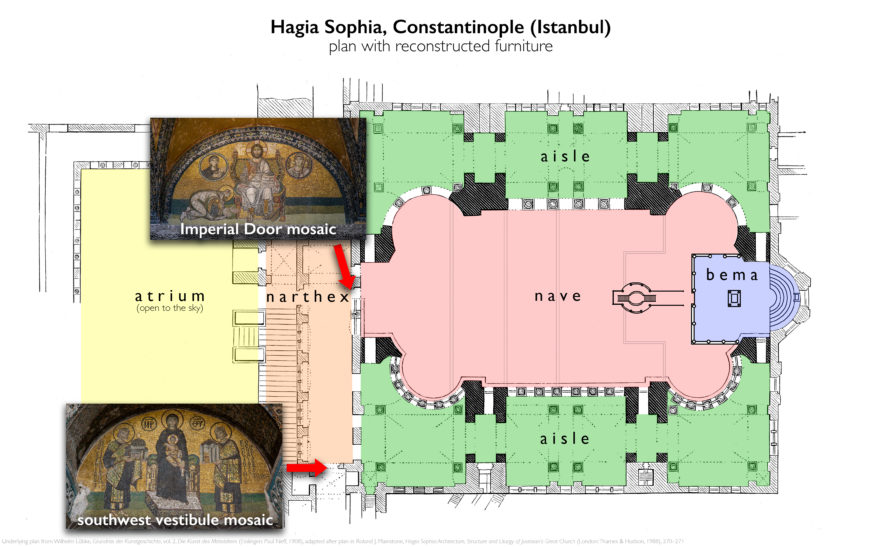

But not all of the images in Hagia Sophia were purely religious in their subject matter. Several mosaics featured images of emperors and empresses: some long dead and others still living at the time when the mosaics were installed. Such images remind us that over the long history of the Byzantine Empire, there was no separation of Church and state. The emperor often participated in Church rituals with the clergy in Hagia Sophia.

Two mosaics depicting emperors were positioned along a ceremonial route by which the emperor sometimes entered Hagia Sophia for the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, as described in the tenth-century Book of Ceremonies.

Southwest vestibule

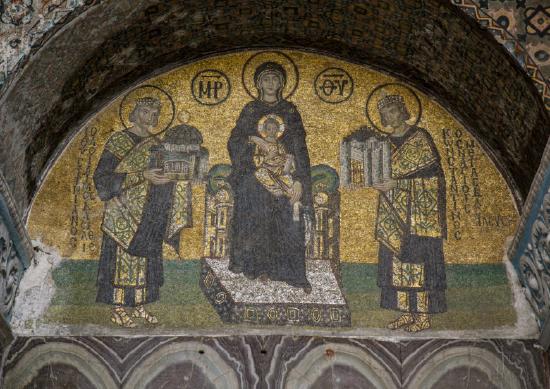

As they entered the narthex of Hagia Sophia, living emperors would have passed under a mosaic of great emperors from centuries past (see Figure \(\PageIndex{42}\)). This mosaic appears in a lunette in the southwest vestibule and was likely installed in the early tenth century.

A towering image of the Virgin appears at the center, flanked by large letters identifying her as the “Mother of God.” She holds the Christ Child on her lap and sits on a lavish throne, resting her feet on a jeweled footstool (see Figure \(\PageIndex{44}\)). This central image of the Virgin and Child is similar to the ninth-century image in Hagia Sophia’s apse discussed in Figure \(\PageIndex{38}\), which the emperor would encounter as he continued into the church.

On the right, emperor Constantine, who founded Constantinople in 330 C.E., offers a model of the city, with its high crenelated walls, to the Virgin and Child. On the left, emperor Justinian, who built Hagia Sophia between 532–537, offers a domed model of Hagia Sophia—the very church in which this mosaic is located—to the Virgin and Child. Images showing donors offering smaller models of the buildings they had built to heavenly figures were common in medieval art. Both emperors wear the imperial loros, a rich sash-like garment that was often decorated with precious stones. The mosaic highlights the Byzantine understanding of the Virgin as protector of Constantinople, as well as the importance of imperial patronage.

Imperial Door

As the emperor continued his ceremonial entrance into Hagia Sophia, he proceeded into the main part of the church through the “Imperial Door,” the central door between the inner narthex and the nave. A mosaic dated to around 900, probably slightly earlier than the mosaic in the southwest vestibule, appears in the lunette above the Imperial Door (see Figures \(\PageIndex{45}\) and \(\PageIndex{46}\)). In this mosaic, a frontal Christ sits formally on a lyre-backed throne. He blesses the viewer with his right hand and rests an open book on his left knee, which displays the text: “Peace be with you; I am the light of the world” (a paraphrase of John 20:19 and John 8:12). Two roundels flank Christ. An angel appears within the roundel on Christ’s left. On his right, a woman who is probably the Virgin Mary extends her hands toward Christ in a gesture of supplication.

Below the Virgin, an unnamed emperor with similarly outstretched hands bows before Christ in a gesture of reverence known as proskynesis. Who is this emperor? Several theories have been proposed. Some have understood the emperor as Leo VI atoning for marrying four times—considered a sin and even illegal—in pursuit of a male heir. More recently, scholars have questioned whether this mosaic even represents a specific, historical ruler, or whether it is a more generalized representation of imperial submission to Christ. This image certainly would have been meaningful when emperors performed their own acts of proskynesis here in the narthex (as described in the Book of Ceremonies) before passing beneath this mosaic to enter the nave of the church.

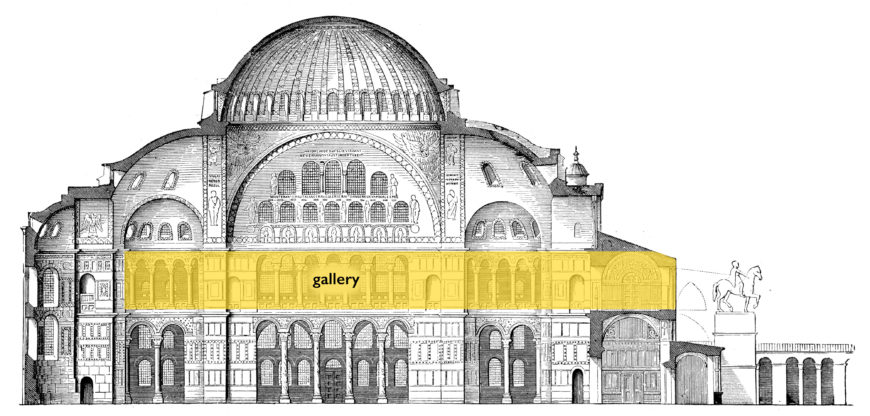

Imperial patrons

Two additional mosaics were added to Hagia Sophia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Their subjects and location are closely related. Both depict emperors and empresses and are located in the south gallery (on the second level, above the south aisle, Figure \(\PageIndex{48}\))—which was traditionally reserved for imperial use during church services—near a doorway that connected Hagia Sophia with the Great Palace.

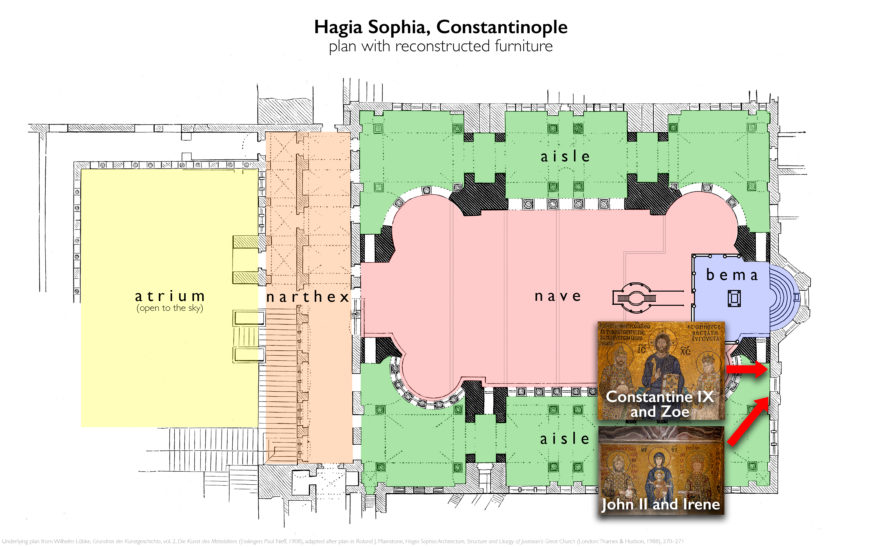

Constantine IX and Zoe with Christ

In the first mosaic, added during the waning years of the Macedonian dynasty, Christ appears enthroned at the center, flanked by an emperor and empress (see Figure \(\PageIndex{49}\)). When it was first installed between 1028–1034, this mosaic probably depicted empress Zoe and her first husband, Romanos III. The mosaic would have commemorated an imperial donation to Hagia Sophia, when the capitals of the Great Church were gilded.

But the mosaic was subsequently altered between 1042–1055, replacing Romanos III with Zoe’s third husband, Constantine IX Monomachos (who was also a patron of Nea Moni on Chios, known for its lavish mosaic decoration). This revised version of the mosaic, which survives today, probably commemorated another imperial donation to the Hagia Sophia, one which enabled the Divine Liturgy to be celebrated in the Great Church every day rather than only on weekends (the cost of putting on a service in Hagia Sophia—including paying the large number of clergy and staff—was considerable). Constantine IX and Zoe turn inward toward Christ, offering a bag of money and what is probably a contract of donation. This image illustrates how such donations to the Church were understood as offerings to God.

Curiously, when the identity of the emperor was updated, Zoe and Christ were also given new faces. Perhaps the goal was to give all three faces a consistent stylistic appearance. Another theory suggests that Zoe’s original face may have been destroyed as an act of damnatio memoriae (the official erasure of someone’s legacy) when Zoe was briefly exiled before her third marriage, and therefore needed to be replaced.

John II and Irene

A similar imperial mosaic was installed c. 1118–1134 beside the image of Constantine and Zoe in the south gallery. It is the only surviving mosaic from twelfth-century Constantinople. The Virgin and Child appear at the center, complimenting the nearby image of Christ (see Figure \(\PageIndex{52}\)). On either side, emperor John II of the Komnenian dynasty and empress Irene of Hungary occupy the same positions as Constantine IX and Zoe in the earlier mosaic, similarly offering a money bag and a rolled document.

These emperors and empresses in the south gallery all appear shorter than the important central figures of Christ and the Virgin whom they flank. At the same time, the closeness of these haloed emperors and empresses to Christ and the Virgin suggests the considerable power of these Byzantine rulers, who immortalized themselves in fields of gold on the walls of Constantinople’s Great Church.

A work in progress

Although Justinian finished building Hagia Sophia and dedicated it in the year 537, Constantinople’s Great Church was, in a sense, an ongoing work in progress, since subsequent rulers continued to decorate it through the following centuries. When Constantinople was sacked by crusaders in 1204 and subsequently reclaimed by the Byzantines in 1261, Hagia Sophia was again refurbished, and a new mosaic showing the Deësis—an image of intercession and divine mercy—was installed in the south gallery (see Figure \(\PageIndex{53}\)). This last major mosaic was added to the Great Church more than seven centuries after Hagia Sophia’s initial construction.

The continuous addition of mosaics to Hagia Sophia—reflecting theological controversies, imperial donations, and even remarriages—illustrates how the continual creation, or “social life,” of a monument can often be a complex, ongoing process.

Notes:

[1] Arjun Appadurai coined this phrase in his edited volume: The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Byzantine frescoes at Saint Panteleimon, Nerezi

by Dr. Evan Freeman

The Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire is well known for its glittering, gold mosaics. But the medieval artists of Byzantium were also adept at a wall painting technique known as fresco: a less expensive medium than mosaics in which artists applied pigments to wet plaster so that the painting became chemically bonded to the wall itself. A small church located in the village of Gorno Nerezi (commonly just “Nerezi”) on the outskirts of Skopje, North Macedonia, preserves some of the finest examples of fresco from the Byzantine period.

Imperial Patronage

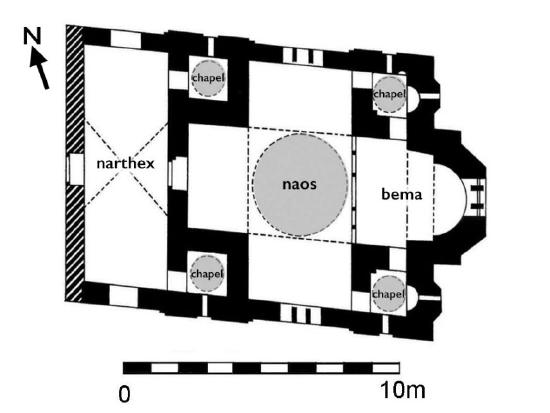

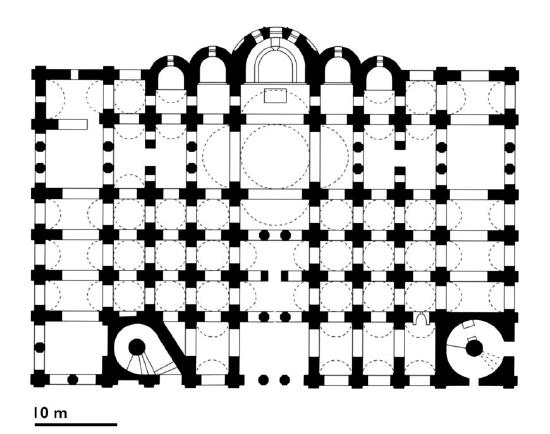

According to a painted inscription in the church, the Middle Byzantine church of Saint Panteleimon (pronounced pan-tah-LAY-mon) was built as a monastery church in 1164 by Alexios Komnenos, a nephew of Byzantine emperor John II (see Figure \(\PageIndex{56}\)). Alexios may have owned land in this region. Nerezi’s five-domed architecture and high-quality frescoes reflect its imperial patronage.

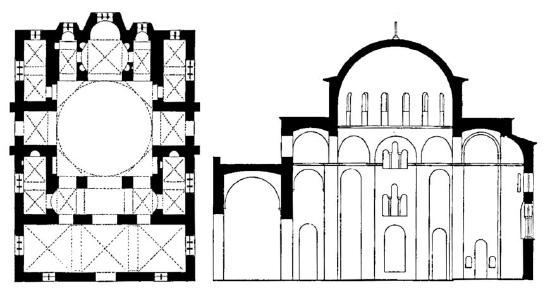

Architecture

Saint Panteleimon is a modest, cross-domed structure with four smaller domed chapels, making it a five-domed church (read more about cross-domed churches anplan in Figure \(\PageIndex{57}\)). Its five-domed design echoes the form of the church of the Holy Apostles in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (destroyed following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453)—which contained relics of the Apostles and the tombs of Byzantine emperors—reflecting Nerezi’s connections with the capital and imperial family.

Like most Byzantine churches, Saint Panteleimon is divided into three main parts, which were adorned with frescoes:

- the narthex at the western end of the church, which functioned as an entrance vestibule;

- the naos—the main part of the church—where most of the worshippers attended church services; and

- the bema, or sanctuary, where the altar was located and where the clergy led the celebration of the Eucharist.

The two eastern chapels connect to the bema, enabling them to function as a prothesis and diakonikon. The two western chapels connect with the narthex and may have been used for services that took place in the narthex.

Frescoes

While the frescoes in the narthex have been badly damaged and the upper portions of the naos and bema were replaced with post-Byzantine paintings, the naos and bema preserve much of the original, twelfth-century frescoes on the lower levels.

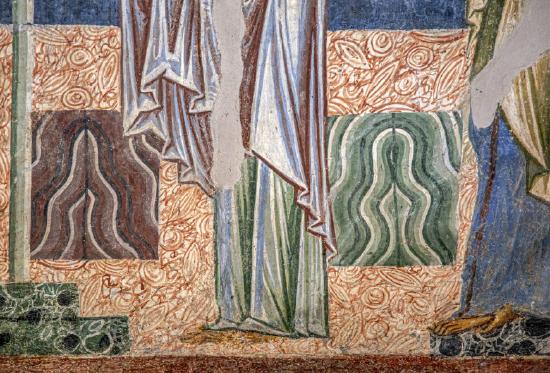

A stunning, blue background unifies the original, twelfth-century frescoes, which have been executed with a range of vivid colors. The figures at Nerezi are slender and often elongated. Nerezi’s painters have made extensive use of lines to define the boundaries of shapes, model forms, and portray emotions in the individualized faces of many of Nerezi’s figures (see Figure \(\PageIndex{58}\)). This elongation of the figures and repetition of lines create a sense of visual rhythms and movement within the church, and were a hallmark of Byzantine painting during the Komnenian period.

The high quality of Nerezi’s frescoes and similarities with other artworks have led many scholars to conclude that the church’s painters hailed from the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, a major center of artistic patronage and production. Nerezi’s frescoes are particularly valuable since no painted church programs from Constantinople survive from this period (much of Constantinople’s church art was destroyed following the Ottoman conquest of the city in 1453).

The Naos

As was common in post-Iconoclastic churches, Nerezi features full-length, nearly life-size portraits of saints at the floor level, with narrative scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary (see Figure \(\PageIndex{59}\)).

The Meeting of the Lord in the Temple

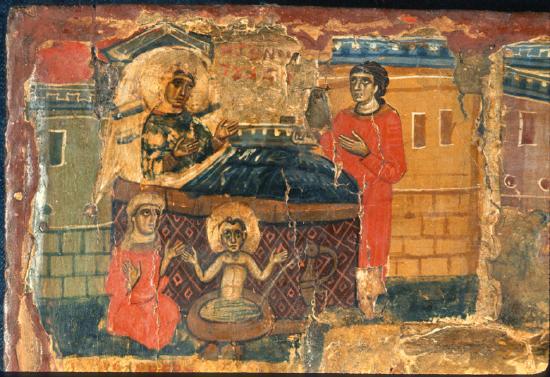

This narrative cycle begins on the southern crossarm of the naos, which is dominated by a large image of the Meeting of the Lord in the Temple. Here, Mary and Joseph bring the newborn Jesus into the Jewish temple and the prophets Simeon and Anna identify him as the Messiah (view annotated image).

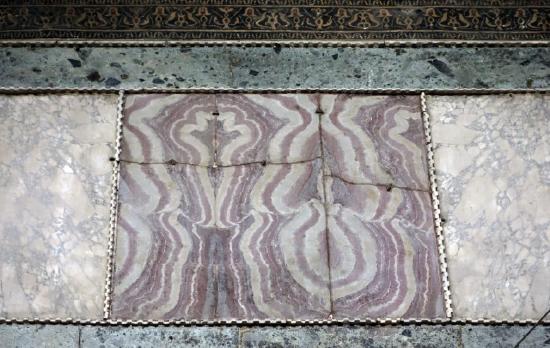

The artists have imagined the interior of the temple as a Christian church with an altar, ciborium, and marble revetment (including bookmatched marble slabs like those found in Justinian’s sixth-century Hagia Sophia and other Byzantine churches).

The Deposition

Christ’s followers mourn his death on the north side of the naos, a common theme of hymns and sermons during the post-Iconoclastic era.

In the Deposition, Christ’s followers remove his body from the cross. Joseph of Arimathea looks out at the viewer with a piercing gaze from the center of the scene.

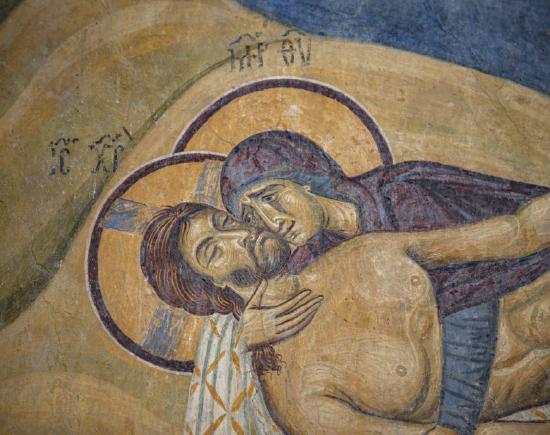

The Lamentation

The narrative continues with the Threnos, or Lamentation, located next to the Deposition. The dead Christ now lies on the ground but has not yet been placed in the tomb (see Figures \(\PageIndex{64}\), \(\PageIndex{66}\), \(\PageIndex{67}\), and \(\PageIndex{68}\), left). Christ’s followers mourn his death. Lines of grief crease their faces, creating emotional expressions often absent from Byzantine art. The Virgin cradles her dead son in her lap, recalling how she carried him into the temple in the Meeting of the Lord on the opposite wall. (View annotated image.)

John the Evangelist clings to Christ’s hand at the center of the scene. His hunched body creates sweeping contours that move the viewer’s eyes toward the dead Christ and his mother. Additional mourners gather at Christ’s feet and angels appear in the sky above, echoing the grief of Christ’s followers below. These human and angelic figures display a range of emotions and gestures of bereavement, which must have invited Byzantine viewers to engage emotionally with this image.

In Byzantine mosaics and panel paintings, such scenes often appeared against a solid gold background. Yet here, the artist has effectively employed fresco to create a naturalistic environment: an undulating green ground, tan hills with rhythmic curves, and a deep blue sky. This landscape also serves the larger composition; the silhouettes of the hills sink toward the center of the scene, moving the viewer’s eyes to the figures, and heightening the overall drama of the image.

This scene, its naturalistic setting, and its emphasis on emotion all anticipate developments associated with Renaissance Italy. Scholars have noted the striking similarities between Nerezi and Giotto’s fourteenth-century frescoes at the Arena Chapel in Padua, Italy, particularly in Giotto’s own rendition of this same scene: The Lamentation (see Figure \(\PageIndex{68}\), right). Although Giotto’s figures are more naturalistic than those at Nerezi, both frescoes emphasize the mourners’ grief within a landscape that amplifies the drama of the scene.

The Templon

A templon separates the naos (where most worshippers stood) from the bema (where the clergy stood around the altar), reconstructed from twelfth-century fragments (view location in plan). This form of sanctuary barrier, consisting of chancel slabs, colonnettes, and an epistyle or templon beam, was widespread in Byzantium during this time, and enabled laypeople to see into the bema. Later, Byzantine templons incorporated intercolumnar icons (as seen at the fourteenth-century church of Saint George of Staro Nagoričino) creating what has become known as an “iconostasis,” which can still be found in Orthodox churches today.

Proskynetaria icons

As was common in Middle Byzantine churches, the church of Saint Panteleimon features two large proskynetaria icons on either side of the templon. The damaged icon to the north once depicted the Virgin and child, resonating with the narrative depictions of these figures in such scenes as the Meeting of the Lord and the Lamentation. The icon to the south represents Saint Panteleimon, a healer who was the church’s patron saint (see Figure \(\PageIndex{71}\)). Panteleimon retains his original stucco frame, which features delicately carved birds and vegetal motifs. The large scale, prominent position, and elaborate frames of these proskynetaria icons must have made them a focus of prayer and veneration for Byzantine worshippers.

Bishops in the Bema

The bema, where the clergy celebrated the Eucharist, displays images that reflect the ritual function of this particular space. Eight bishop saints decorate the bema walls at ground level, two of whom appear to emerge from the side chapels. Images of bishops were a common feature in Byzantine bemas for centuries, where they were usually depicted frontally and holding books, as with the mosaic of Saint Severus at the sixth-century church of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, near Ravenna, Italy (see Figure \(\PageIndex{73}\)).

But the bishops at Nerezi appear in a three-quarter view and strike a more dynamic pose, an innovative approach at this time (see Figure \(\PageIndex{74}\)). Instead of closed books, the bishops at Nerezi hold unfurled scrolls, or “rolls," that display prayers spoken by the clergy in the Divine Liturgy. Such scrolls were actually used by clergy during this period, as seen in a roughly contemporary, twelfth-century example preserved at the British Library.

This new way of depicting bishops in a three-quarter pose and accompanied by contemporary liturgical objects made these saints appear as active participants in the church services celebrated in this space.

In the apse behind the altar, two angels vested as deacons hold liturgical fans, another contemporary liturgical object (see Figure \(\PageIndex{76}\)), on either side of the Hetoimasia, or “prepared throne,” a symbolic image that evoked Christ’s Passion and anticipated second coming (see Figure \(\PageIndex{75}\)). Additional angel deacons appear above, where Christ is shown giving Eucharistic bread and wine to his Apostles like a priest, mirroring the Divine Liturgy as it unfolded below. (View annotated image.)

Scholars refer to this tendency of church art to illustrate contemporary ritual and material culture during this period as “liturgical realism.”

Nerezi in art history

Byzantine art may be known for its golden mosaics, but the five-domed church of Saint Panteleimon at Nerezi challenges modern viewers not to forget Byzantium’s equally beautiful frescoes. With vivid colors and graceful lines, Nerezi’s frescoes depict elongated figures that exhibit a range of emotions and sometimes occupy naturalistic landscapes, anticipating the Italian Renaissance and demonstrating Byzantium’s importance in the history of art (see Figure \(\PageIndex{77}\)).

Mosaics and microcosm: the monasteries of Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni

by Dr. Evan Freeman

Ecstatic Motion

The city of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire since its foundation by Constantine in 330 C.E., was roiled by the Iconoclastic Controversy in the 8th and 9th centuries. Emperors, bishops, and many others debated whether images, or “icons,” of God and the saints were holy or heretical. Those in favor of images triumphed in 843. Soon after, a new church was built in Constantinople’s great imperial palace and adorned with rich mosaic icons. The church was dedicated to the Virgin of the Pharos, named with the Greek word for a lighthouse, since a lighthouse stood nearby. Around 864, patriarch Photios of Constantinople—the highest-ranking cleric in the empire—gushed about the church of the Pharos and its glittering mosaics: “It is as if one had entered heaven itself... and was illuminated by the beauty in all forms shining all around like so many stars, so is one utterly amazed.” Photios describes how his whirling to view the church produced the impression that the church itself was moving:

It seems that everything is in ecstatic motion, and the church itself is circling round. For the spectator, through his whirling about in all directions and being constantly astir, which he is forced to experience by the variegated spectacle on all sides, imagines that his personal condition is transferred to the object. Photios of Constantinople, Homily 10

Photios offers us a tantalizing impression of the Pharos church and a sense of how Byzantines viewed mosaics during this period.

Middle Byzantine mosaics

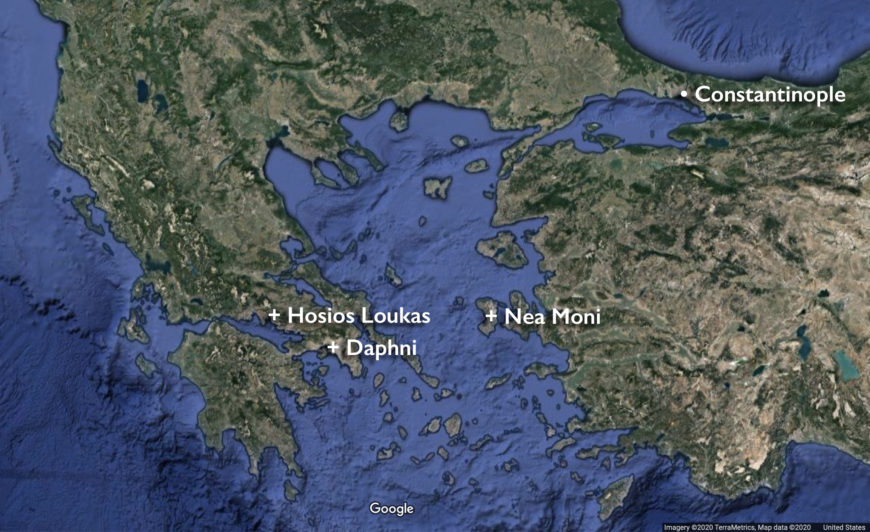

While the church of the Pharos has been lost, three churches from around the eleventh century preserve much of their original mosaic programs, which were likely inspired by churches like the church of the Pharos in the capital. These three monuments—Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni—point to common trends in Middle Byzantine mosaics, while also demonstrating the flexibility of church decoration during this period.

Mosaics are patterns or images made of tesserae: small pieces of stone, glass, or other materials. They commonly adorned floors in antiquity but became popular decoration for church walls and ceilings in Byzantium, especially among wealthy patrons such as emperors.

In the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843–1204), domed, centrally planned churches became more popular than the long, hall-like basilicas of previous centuries. While basilicas created a strong horizontal axis between the entrance on one end and the altar at the other, domed churches added a vertical axis that prompted viewers to look upward. New decorative programs developed in tandem with this architectural trend, covering walls and domes with mosaics and frescos of holy figures in complex, new configurations. The lower portions of churches were often decorated with marble revetment (thin panels of marble, often beautifully colored).

Church as microcosm

Byzantine texts interpreted the domed church as a microcosm—a three-dimensional image of the cosmos—associating the sparkling gold vaults above with the heavens, and the colored marbles below with the earth. Within this framework, images often seem to be arranged hierarchically: with a heavenly Christ reigning above, events from sacred history unfolding below, and portraits of saints surrounding the worshippers in the lowest registers. Many of these images took on additional meanings as church services unfolded.

Spatial icons

The mosaicists who decorated these churches made no effort to create illusionistic backdrops for the holy figures, as one often finds in works from the Italian Renaissance, such as Masaccio’s Holy Trinity fresco (Figure \(\PageIndex{81}\)). Instead, the holy figures situated in the curves and facets of these Middle Byzantine churches appear against a gold ground. Often, these prophets, saints, and angels seem to face and even communicate with each other across the space of the church. Such “spatial icons”—as the art historian Otto Demus famously described them—created the impression that the holy figures occupied the same physical space as the worshippers.

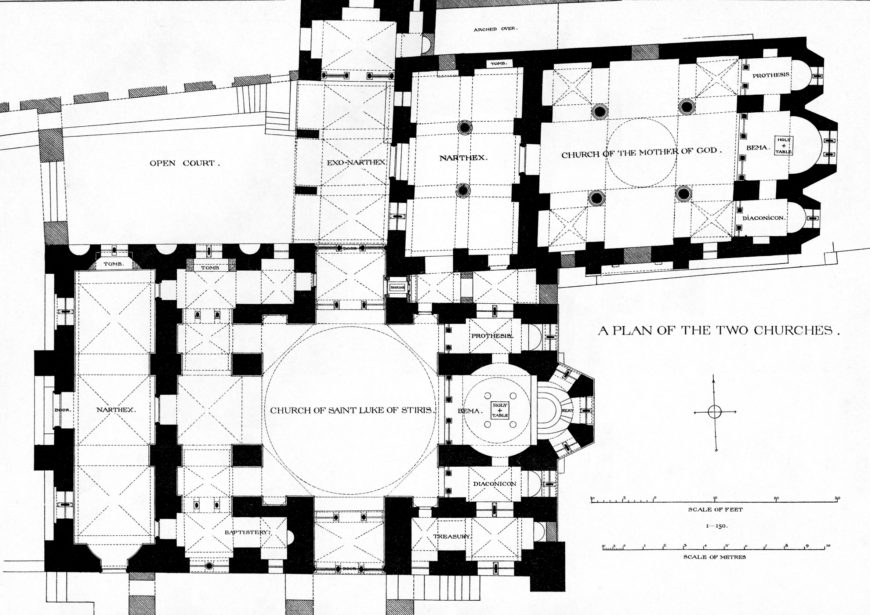

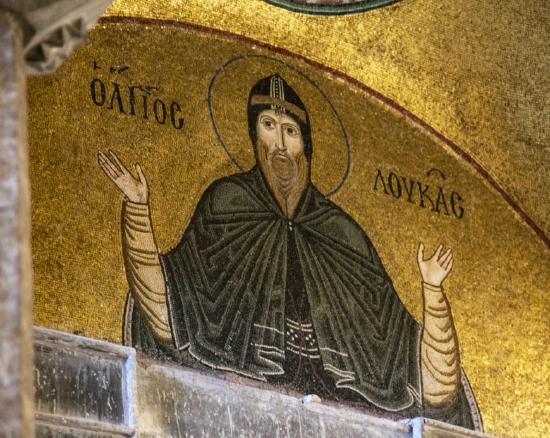

Hosios Loukas

The monastery of Hosios Loukas, located in central Greece, is probably the oldest of the three churches. It is named for St. Loukas of Steiris, a local monastic saint who lived on this site and died in 953. Two connected churches survive here. The older church, dedicated to the Virgin and located to the north, features a cross-in-square plan. The katholikon church, built to the south in the eleventh century, utilizes a larger, octagon-domed plan (read more about these church types). The katholikon church retains many of its mosaics, undoubtedly the result of rich patronage. St. Luke’s body was interred between the two churches, and the monastery attracted pilgrims who sought the saint’s healing.

Worshippers entered the katholikon through the “narthex,” a vestibule at the western end of the building. Here, they encountered portraits of saints and large images of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection: Christ washing his disciples’ feet, the Crucifixion, the Anastasis, and the incredulous Thomas touching the wounds of the risen Christ.

Worshippers then passed beneath a large mosaic of Christ Pantokrator to enter the main part of the church, or “naos.” Christ displays an open book that proclaims him to be the “light of the world” (John 8:12). The mosaic’s gold tesserae reflect sunlight from the front door in the daytime, and flickering candlelight at night.

A large fresco of Christ surrounded by angels occupies the heavenly space of the dome in the naos. This fresco may replicate the original dome mosaics, which have been lost. Four squinches beneath the dome displayed mosaic images from the life of Christ. The Annunciation likely once adorned the northeast squinch but has been lost. The mosaics in the other three squinches depict Christ’s Nativity, Presentation in the Jewish Temple, and Baptism.

Various saints appear below. An abundance of monastic saints—including St. Loukas himself—reflects the building’s function as a monastery church.

Proceeding through the naos, worshippers saw an image of the descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles at Pentecost in a smaller dome above the altar. The Virgin and Child sit enthroned in the apse behind the altar, a reminder that God became a human being for the salvation of the world. During the Divine Liturgy, this image of Christ’s incarnation took on new significance as the bread and wine also became the body and blood of Christ.

Nea Moni

Hermit monks founded Nea Moni (“new monastery”) on the island of Chios sometime before 1042, and its katholikon was built with the patronage of emperor Constantine IX Monomachos between 1049–1055. It features a rectangular plan, and its architectural design may have been adapted to accommodate its mosaic program.

In the narthex, worshippers again encountered an array of saints and large narrative images centering around Christ’s Passion. In the naos, the main dome has lost its mosaics. But remnants of cherubim and seraphim, evangelists, and apostles inhabit pendentives beneath the dome. Further down, eight alternating conches and niches displayed a ring scenes from the life of Christ. The Virgin appears in the eastern apse behind the altar with hands upraised in prayer, flanked by the archangels Gabriel and Michael.

Figure \(\PageIndex{92}\): Daphni Monastery seen from the east, Chaidari, c. 1050–1150. (Photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Daphni

The monastery of Daphni, located just northwest of Athens, was likely the last of the three churches to be built, probably constructed between 1050–1150. Little is known about the foundation of this cross-in-square church.

Here, the narthex combines scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin, suggesting the church may have been dedicated to Mary. Notably, the Last Supper and Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (where she was fed with heavenly bread by an angel) both appear on the eastern wall of the narthex, where worshippers would have seen them as they entered the church. Such images were meant to connect past events from sacred history with the celebration of the Eucharist in the present: Christ sharing bread and wine with his apostles at the Last Supper and Virgin eating heavenly bread in the temple were both understood to prefigure and symbolize the Eucharist. The appearance of the Foot Washing in the narthexes of all three of these churches may reflect the use of this part of the church for a ritual foot washing on Holy Thursday, when abbots imitated Christ by washing the feet of the monks.

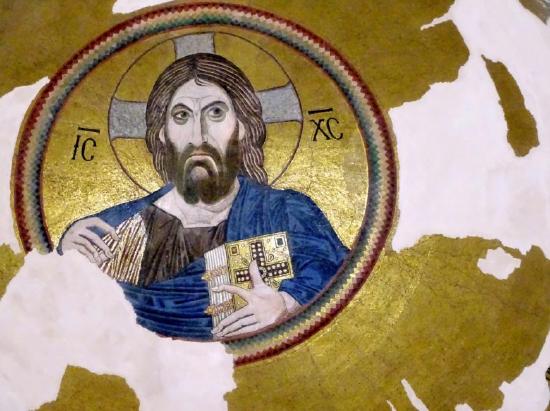

A monumental image of the heavenly Christ Pantokrator, framed by a rainbow mandorla in the central dome, dominates the naos. Photios interprets what must have been a similar image in the Pharos church as Christ reigning from the heavens:

You might say He is overseeing the earth, and devising its orderly arrangement and government, so accurately has the painter been inspired to represent, though only in forms and in colors, the Creator’s care for us. Photios of Constantinople, Homily 10

Scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin—such as the Annunciation—unfold in the squinches below and throughout the rest of the naos. The eastern apse reveals another Virgin and Child, and additional saints appear throughout the naos.

For worshippers entering these churches, mosaics offered a vision of God reigning from on high, a reminder of salvation history, and face-to-face encounters with so many saints who had come before. No wonder Photios found himself whirling around, trying to take in the overwhelming mosaics at the Pharos church, and feeling as if he had “entered heaven itself.”

The Paris Psalter

by Dr. Anne McClanan

The classical past and the medieval Christian present

Why would a Biblical king surround himself with pagans? The Paris Psalter embodies a complex mixture of the classical pagan past and the medieval Christian present—all brought together to communicate a political message by the Byzantine emperor.

The Byzantine Empire, which ruled areas of the eastern Mediterranean from the fourth through fifteenth centuries, left a dazzling visual legacy that has influenced other medieval Christian and Islamic societies as well as countless artists in our own time.

What is a psalter?

The word “Psalter” in the name of this manuscript is the term we use for books and manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Psalms. Psalters were one of the most commonly copied works in the Middle Ages because of their central role in medieval church ceremony.

The images

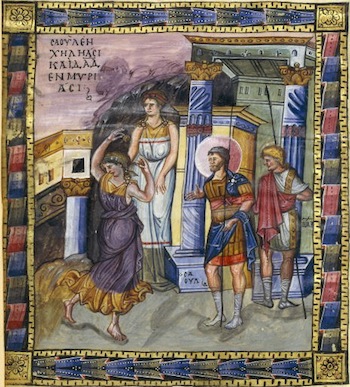

This work was unusually large and lavishly illustrated, with 14 full-page illuminations included in its 449 folios (a folio is a leaf in a book). Eight of these images depict the life of King David, who was often seen as a model of just rule for medieval kings. Because King David was traditionally considered the author of the Psalms, he is shown here in the role of musician and composer, sitting atop a boulder playing his harp in an idyllic pastoral setting.

This manuscript so carefully follows models from prior centuries that scholars once thought it was made during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian in the sixth century. Only later did research demonstrate that the Paris Psalter was actually made in the tenth century as an exquisite imitation of Roman work from the third to fifth centuries—in other words, it was part of an intentional revival of the Classical past. Classical style, as a general term, refers to the naturalistic visual representation used during periods when, for example, the Roman emperors Augustus and Hadrian ruled.

Classical revival

The period of classical revival that produced the Paris Psalter is sometimes called the Macedonian Renaissance, because the Macedonian dynasty of emperors ruled the Byzantine Empire at the time. This classical revival followed Byzantine Iconoclasm. The notion that this Byzantine revival of the Roman past was a Renaissance, in the sense of a full-scale revival of classical thinking and art such as in the Italian Renaissance, has been questioned. However, there is no doubt that we see in this, and other contemporary works, a conscious appropriation of elements of the classical artistic vocabulary.

Thus we have the conundrum of the Biblical David encircled by classical personifications, a figure that represents a place or attribute. In this example, the seated woman embodies the attribute of Melody. David’s seated posture with his instrument is likely based on the classical tragic figure Orpheus, usually shown similarly positioned holding his lyre. Likewise the hazy buildings in the background also belong to the Greco-Roman tradition of wall painting. The meaning of the personifications such as the woman, Melody, perched beside David, is intriguing—within the medieval Christian context she presumably has now become a symbol of culture and erudition as opposed to her earlier significance as a minor deity in the pagan classical world.

Notice how the surroundings including plants, animals and landscape differs from the resplendent gold backgrounds used in the imperial mosaics of Justinian and Theodora at Ravenna or the icon we call the Vladimir Virgin. In contrast, David is depicted naturalistically as a youthful shepherd, rather than the grand king he was to become. The classicizing, more realistic style of the figures and the landscape coupled with the overt classical allusions made by the personifications show the pains taken to render a coherent vision uniting subject and style.

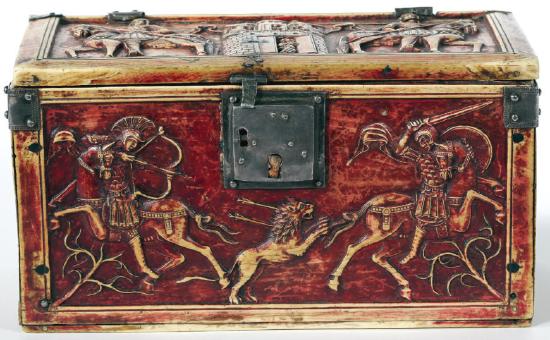

Connecting with great emperors of the past?

Other Byzantine art from the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, such as the ivory Veroli Casket (see Figure \(\PageIndex{100}\)), also show a renewed interest in classicism that called upon Late Roman artistic models. The patron of the Paris Psalter perhaps sought to liken himself this way with great emperors of the past by reviving a style that had been out of favor for hundreds of years and perhaps evoked a “golden age.” Choice of artistic style could function as a tool for conveying meaning within the sophisticated Byzantine society at the time.

The Paris Psalter was produced in Constantinople, today known as Istanbul, and takes its name from its modern location, Paris’ Bibliothèque Nationale. The Paris Psalter manuscript, like most western medieval manuscripts, was not made from paper, but from carefully prepared animal skins. Medieval manuscripts were far more rare and precious than mass-produced modern printed books. Large-scale examples, such as this, made for an aristocratic if not imperial patron, show how Biblical art of the highest craftsmanship could serve many purposes for its medieval audience and patrons.

Middle Byzantine secular art

by Dr. Anne McClanan

For many of us, “Byzantine art” evokes gold icons with sacred figures or splendid church interiors. But the Byzantines also created art and architecture with no religious imagery and without explicit religious functions in mind.

Religious vs. secular?

Admittedly, classifying medieval art in tidy categories of the “religious” or “secular” is a bit anachronistic, especially in the arts of the Byzantine court, where religious and political elements were often seamlessly blended. For example, the Book of Ceremonies, compiled in the 10th century, describes the elaborate protocols that shaped life in the Byzantine palaces, and many—such as the coronation of a new emperor or empress—involve aspects that we would today call both religious and political.

The Book of Ceremonies describes the patriarch, a bishop who was the highest-ranking church official in Constantinople, crowning the emperor in the cathedral of Hagia Sophia:

[The patriarch] says a prayer over the ruler’s imperial crown, and having completed it, the patriarch himself takes the crown and places it on the ruler’s head. Immediately the people cry out, “Holy, holy, holy! Glory to God in the highest and peace on earth,” three times. Then: “Many years to so-and-so, great emperor and sovereign!” Book of Ceremonies I, 38

An image in the twelfth-century Madrid Skylitzes, which shows the patriarch crowning emperor Constantine II, offers us a glimpse of what such a coronation event might have looked like. Such texts and images demonstrate that the sacred and secular often mingled in Byzantium. Acknowledging this, let us nevertheless consider Middle Byzantine “secular” artworks that display non-religious images and motifs.

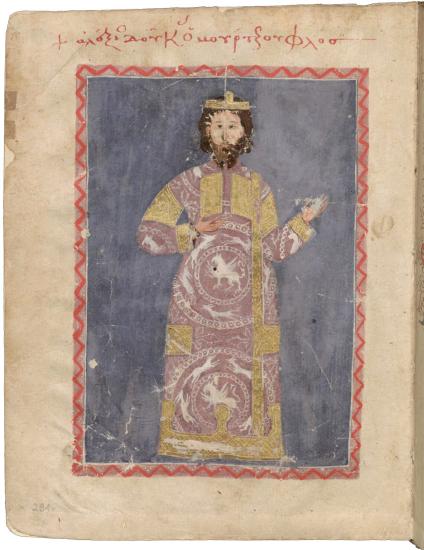

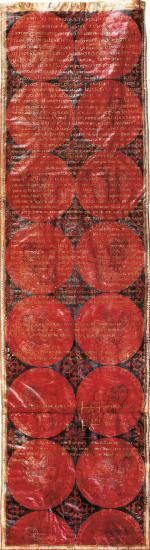

Silks

Manuscript illuminations show the gorgeous silk ceremonial garb of the court, as seen in this depiction of emperor Alexios V, whose brief reign ended with the Fourth Crusade‘s conquest of Constantinople in 1204 (see Figure \(\PageIndex{103}\)). The emperor wears deep purple silk, not decorated with religious motifs, but with white medallion patterns that display a griffin at the center. Similar textiles survive, including an example at the cathedral treasury in Sion, Switzerland.

Although brownish-looking now, chemical analysis shows this Byzantine textile once had the rich purple hue seen in the manuscript since the silk was dyed with “murex,” an extremely expensive purple dye whose use was tightly restricted to the highest echelons of Byzantine society (see Figure \(\PageIndex{104}\)). The shared griffin imagery on both the manuscript illumination garment and Sion textile is typical of luxury goods, which often featured exotic and fictive creatures. The griffin is a mythical creature with the head and wings of an eagle, the body of a lion, and sometimes a snake for a tail, which originated in the ancient world and appears in the arts of many cultures.

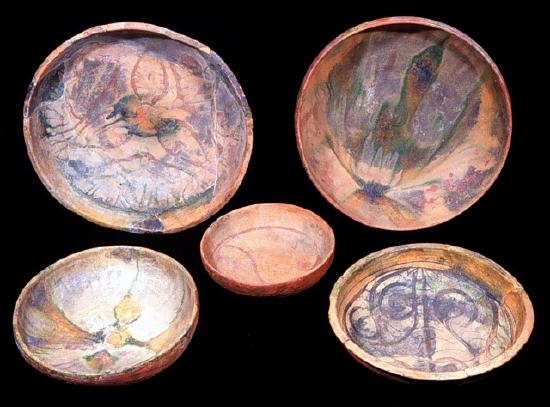

Ceramics

A menagerie of strange beasts also populates Byzantine ceramics. A twelfth-century plate, recovered from a medieval shipwreck, shows a cheetah attacking a deer.

Other Byzantine ceramic vessels featured abstract ornaments or even scenes from popular stories, such as this thirteenth-century plate that might render a scene from the tales of Digenis Akritis which roughly translates as “biracial border lord.” The Digenis Akritis is a Byzantine poem of the twelfth century that narrates the exploits of a fictional hero of Byzantine and Arab descent named Basil on the eastern frontier of the Byzantine empire.

The plate shows a woman perched on the lap of a young man. It includes details such as the rabbit on the right, which broadcasts the amorous intentions of the central figures, since this animal symbolized fecundity and sex to its medieval audience.

Ivory Boxes

A similar playfulness is seen in the imagery of Middle Byzantine ivory and bone boxes, or caskets, of which over forty survive. Additional panels also survive, detached from boxes that are now lost. While some caskets display Biblical figures such as Adam and Eve, many instead portray an eclectic array of figures that seem calculated to delight rather than edify.

The tenth-century Veroli Casket includes scenes from classical mythology such as the hero Bellerophon with his winged horse Pegasus (see Figures \(\PageIndex{101}\), \(\PageIndex{107}\), and \(\PageIndex{108}\)).

Strips of ivory decorated with rosettes, which frame the scenes on the Veroli Casket, are another common characteristic of such boxes. Carved pieces of bone and wood attach to a wooden armature, which come in a few standard shapes. Earlier scholarship assumed these lavish works were made for women, but there is no imagery or other evidence that suggests they were seen as particularly feminine. Instead, what is clear is the use of classical, pagan imagery to signal the erudition and status of the owners, who may have used such boxes to store a range of precious objects.

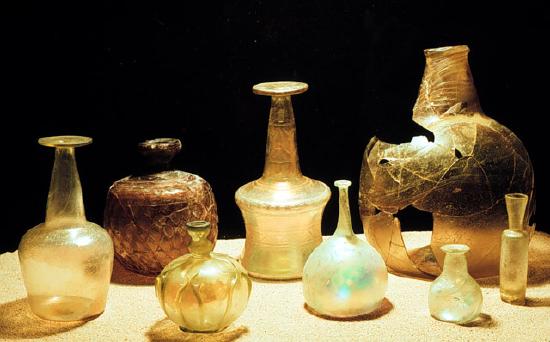

San Marco bowl

An exquisite tenth-century glass bowl now in Venice’s San Marco illustrates another way the classical is rendered in Middle Byzantine art (see Figures \(\PageIndex{109}\) and \(\PageIndex{110}\)).

Various attempts have been made to connect the imagery on the San Marco bowl with specific classical myths, identifying such figures as Dionysus, Hermes, and Mars. But none of those explanations have ultimately been persuasive. The elegantly-posed nudes on the bowl, pictured in dramatic contrast with the dark enamel background, convey a loose sense of the classical rather than recounting a specific myth. A medieval audience would have recognized this object to be of the highest quality in terms of workmanship and value, and the classicizing rendering of figures, which vaguely allude to mythological scenes, further enhanced its status. Perhaps the scenes were inspired by ancient carved gems—such as this carnelian ring stone at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Figure \(\PageIndex{111}\)—which similarly show vignettes in silhouette?

Like the Veroli Casket and the Paris Psalter, the San Marco bowl has been attributed to the so-called “Macedonian Renaissance,” a phase of Middle Byzantine art soon after the end of Iconoclasm in which classical subject matter and a more naturalistic style were preferred by patrons of the Macedonian imperial family.

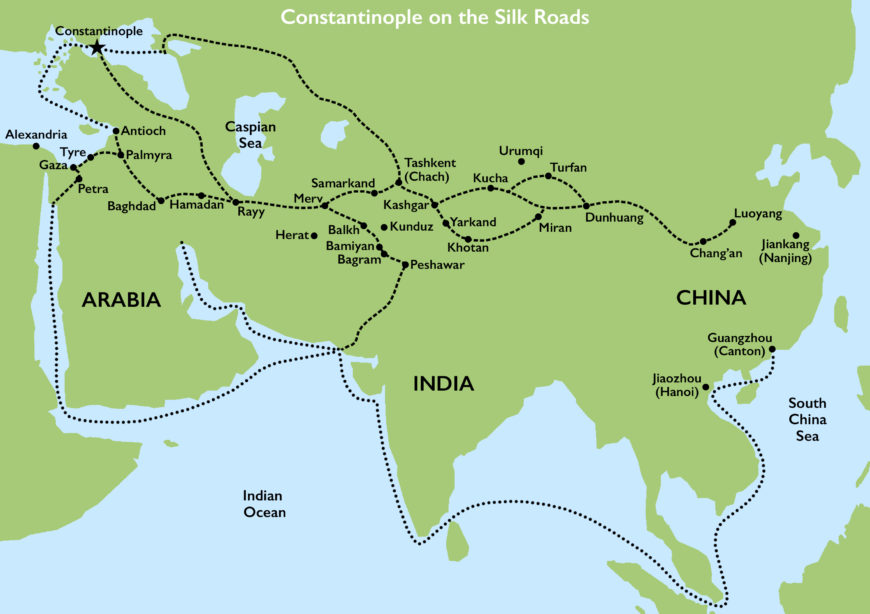

This bowl also references contemporary luxury goods from the Islamic world that were circulating around the eastern Mediterranean at this time. Around the inside of its rim and exterior of its base, the bowl displays pseudo-Arabic inscriptions. These are an imitation of a Kufic script, but they are not actual, readable texts. Alicia Walker has theorized that these classicizing figures and pseudo-Arabic inscriptions indicate that this vessel may have been used for divination, which was associated with ancient gods and eastern cultures. [1] But the significance of these non-Christian motifs remains uncertain.