12.2: Christian Art Before Constantine

- Page ID

- 108671

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Christianity, an introduction

by Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Nancy Ross and Dr. Steven Zucker

How little we know

Almost nothing is known about Jesus beyond biblical accounts, although we do know quite a bit more about the cultural and political context in which he lived—for example, Jerusalem in the first century. What follows is an introductory historical summary of Christianity. It hardly needs stating that there are many interpretations and disagreements among historians.

Jesus v. Rome

The biblical Jesus, described in the Gospels as the son of a carpenter, was a Jew and a champion of the underdog. He rebelled against the occupying Roman government in what was then Palestine (at this point the Roman Empire stretched across the Mediterranean). He was crucified for upsetting the social order and challenging the authority of the Romans and their local Jewish leaders. The Romans crucified Jesus, a typical method of execution—especially for those accused of crimes against the government.

Jesus’ followers claim that after three days he rose from the grave and later ascended into heaven. His original followers, known as disciples or apostles, traveled great distances and spread Jesus’ message. His life is recorded in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which are found in the New Testament. “Christ” means messiah or savior (this belief in a savior is a traditional part of Jewish theology).

Old and New Testaments

Early on, there were many ways that Christianity was practiced and understood, and it wasn’t until the 2nd century that Christianity began to be understood as a religion distinct from Judaism (it’s helpful to remember that Judaism itself had many different sects). Christians were sometimes severely persecuted by the Romans. In the early 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine experienced a miraculous conversion and made it legally acceptable to be a Christian. Less than a hundred years later, the Roman Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official state religion.

The first Christians were Jews (whose bible we refer to as the Old Testament or the Hebrew Bible). But soon pagans too converted to this new religion. Christians saw the predictions of the prophets in the Hebrew Bible come to fulfillment in the life of Jesus Christ—hence the “Bible” of the Christians includes both the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament) and the New Testament.

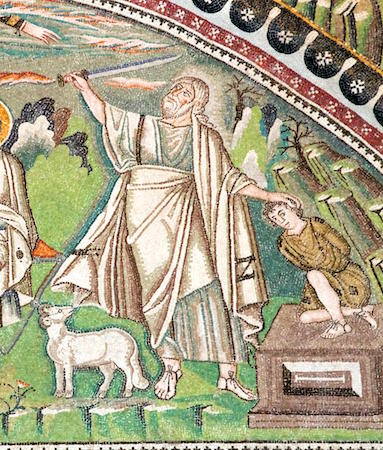

In addition to the fulfillment of prophecy, Christians saw parallels between the events of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. These parallels, or foreshadowings, are called typology. One example would be Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, Isaac, and the later sacrifice of Christ on the cross. We often see these comparisons in Christian art offered as a revelation of God’s plan for the salvation of mankind.

Different Christianities

Unlike Greek and Roman religions (there was both an official “state” religion as well as other cults), Christianity emphasized belief and a personal relationship with God. The doctrines, or main teachings, of Christianity were determined in a series of councils in the early Christian period, such as the Council of Nicea in 325. This resulted in a common statement of belief known as the Nicene Creed, which is still used by some churches today.

Nevertheless, there is great diversity in Christian belief and practice. This was true even in the early days of Christianity, when, for example, Arians (who believed that the three parts of the Holy Trinity were not equal) and Donatists (who held that priests who had renounced their Christian faith during periods of persecution could not administer the sacraments), were considered heretics (someone who goes against official teaching). Today there are approximately 2.2 billion Christians who belong to a multitude of sects.

The two dominant early branches of Christianity were the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, rooted in Western and Eastern Europe respectively. Protestantism (and its different forms) emerged only later, at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Before that there was essentially just one church in Western Europe—what we would call the Roman Catholic church today (to differentiate it from other forms of Christianity in the West such as Lutheranism, Methodism etc.). Christianity spread throughout the world. In the 16th century, the Jesuits (a Catholic order), sent missionaries to Asia, North and South America, and Africa often in concert with Europe’s colonial expansion.

Doctrines

Christianity holds that God has a three-part nature—that God is a trinity (God the father, the Holy Spirit, and Jesus Christ)* and that it was Jesus’ death on the cross—his sacrifice—that allowed for human beings to have the possibility of eternal life in heaven. In Christian theology, Christ is seen as the second Adam, and Mary (Jesus’ mother) is seen as the second Eve. The idea here is that where Adam and Eve caused original sin, and were expelled from paradise (the Garden of Eden), Mary and Christ made it possible for human beings to have eternal life in paradise (heaven), through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

Christian practice centers on the sacrament of the Eucharist, which is sometimes referred to as Communion. Christians eat bread and drink wine to remember Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of humankind. Christ himself initiated this practice at the Last Supper. Catholics and Eastern Orthodox believe that the bread and wine literally transform into the body and blood of Christ, whereas Protestants and other Christians see the Eucharist as symbolic reminder and re-enactment of Christ’s sacrifice.

Christians demonstrate their faith by engaging in good (charitable) works (works of art—like the frescoes by Giotto in the Arena Chapel—were often created as good works). They often engage in rituals, or sacraments, such as partaking of the Eucharist or being baptized. Traditional Christian churches have a hierarchical structure of clergy. Devout men and women sometimes become nuns or monks and may separate themselves from the world and live a cloistered life devoted to prayer in a monastery.

*There are also nontrinitian Christians.

Early Christianity, an introduction

by Dr. Allen Farber

Key events

Two important moments played a critical role in the development of early Christianity:

- The decision of the Apostle Paul to spread Christianity beyond the Jewish communities of Palestine into the Greco-Roman world

- When the Emperor Constantine accepted Christianity and became its patron at the beginning of the fourth century (Constantine is pictured in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) in a fragment of the colossal statue.)

The creation and nature of Christian art were directly impacted by these moments.

The spread of Christianity

As implicit in the names of his Epistles, Paul spread Christianity to the Greek and Roman cities of the ancient Mediterranean world. In cities like Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, and Rome, Paul encountered the religious and cultural experience of the Greco Roman world. This encounter played a major role in the formation of Christianity.

Christianity as a mystery cult

Christianity in its first three centuries was one of a large number of mystery religions that flourished in the Roman world. Religion in the Roman world was divided between the public, inclusive cults of civic religions and the secretive, exclusive mystery cults. The emphasis in the civic cults was on customary practices, especially sacrifices. Since the early history of the polis or city state in Greek culture, the public cults played an important role in defining civic identity.

As it expanded and assimilated more people, Rome continued to use the public religious experience to define the identity of its citizens. The polytheism of the Romans allowed the assimilation of the gods of the people it had conquered.

Thus, when the Emperor Hadrian created the Pantheon in the early second century, the building’s dedication to all the gods signified the Roman ambition of bringing cosmos or order to the gods, just as new and foreign societies were brought into political order through the spread of Roman imperial authority (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). The order of Roman authority on earth is a reflection of the divine cosmos.

For most adherents of mystery cults, there was no contradiction in participating in both the public cults and a mystery cult. The different religious experiences appealed to different aspects of life. In contrast to the civic identity which was at the focus of the public cults, the mystery religions appealed to the participant’s concerns for personal salvation. The mystery cults focused on a central mystery that would only be known by those who had become initiated into the teachings of the cult.

Monotheism

These are characteristics Christianity shares with numerous other mystery cults. In early Christianity emphasis was placed on baptism, which marked the initiation of the convert into the mysteries of the faith. The Christian emphasis on the belief in salvation and an afterlife is consistent with the other mystery cults. The monotheism of Christianity, though, was a crucial difference from the other cults. The refusal of the early Christians to participate in the civic cults due to their monotheistic beliefs lead to their persecution. Christians were seen as anti-social.

Early Christian art

by Dr. Allen Farber

The beginnings of an identifiable Christian art can be traced to the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. Considering the Old Testament prohibitions against graven images, it is important to consider why Christian art developed in the first place. The use of images will be a continuing issue in the history of Christianity. The best explanation for the emergence of Christian art in the early church is due to the important role images played in Greco-Roman culture.

.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=500&height=351)

As Christianity gained converts, these new Christians had been brought up on the value of images in their previous cultural experience and they wanted to continue this in their Christian experience. For example, there was a change in burial practices in the Roman world away from cremation to inhumation. Outside the city walls of Rome, adjacent to major roads, catacombs were dug into the ground to bury the dead. Families would have chambers or cubicula dug to bury their members. Wealthy Romans would also have sarcophagi or marble tombs carved for their burial. The Christian converts wanted the same things. Christian catacombs were dug frequently adjacent to non-Christian ones, and sarcophagi with Christian imagery were apparently popular with the richer Christians.

Junius Bassus, a Roman praefectus urbi or high ranking government administrator, died in 359 CE. Scholars believe that he converted to Christianity shortly before his death accounting for the inclusion of Christ and scenes from the Bible (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

Themes of death and resurrection

A striking aspect of the Christian art of the third century is the absence of the imagery that will dominate later Christian art. We do not find in this early period images of the Nativity, Crucifixion, or Resurrection of Christ, for example. This absence of direct images of the life of Christ is best explained by the status of Christianity as a mystery religion. The story of the Crucifixion and Resurrection would be part of the secrets of the cult.

While not directly representing these central Christian images, the theme of death and resurrection was represented through a series of images, many of which were derived from the Old Testament that echoed the themes. For example, the story of Jonah—being swallowed by a great fish and then after spending three days and three nights in the belly of the beast is vomited out on dry ground—was seen by early Christians as an anticipation or prefiguration of the story of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Images of Jonah, along with those of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, the Three Hebrews in the Firey Furnace, Moses Striking the Rock, among others, are widely popular in the Christian art of the third century, both in paintings and on sarcophagi.

All of these can be seen to allegorically allude to the principal narratives of the life of Christ. The common subject of salvation echoes the major emphasis in the mystery religions on personal salvation. The appearance of these subjects frequently adjacent to each other in the catacombs and sarcophagi can be read as a visual litany: save me Lord as you have saved Jonah from the belly of the great fish, save me Lord as you have saved the Hebrews in the desert, save me Lord as you have saved Daniel in the Lion’s den, etc.

One can imagine that early Christians—who were rallying around the nascent religious authority of the Church against the regular threats of persecution by imperial authority—would find great meaning in the story of Moses of striking the rock to provide water for the Israelites fleeing the authority of the Pharaoh on their exodus to the Promised Land.

Christianity’s canonical texts and the New Testament

One of the major differences between Christianity and the public cults was the central role faith plays in Christianity and the importance of orthodox beliefs. The history of the early Church is marked by the struggle to establish a canonical set of texts and the establishment of orthodox doctrine.

Questions about the nature of the Trinity and Christ would continue to challenge religious authority. Within the civic cults there were no central texts and there were no orthodox doctrinal positions. The emphasis was on maintaining customary traditions. One accepted the existence of the gods, but there was no emphasis on belief in the gods.

The Christian emphasis on orthodox doctrine has its closest parallels in the Greek and Roman world to the role of philosophy. Schools of philosophy centered around the teachings or doctrines of a particular teacher. The schools of philosophy proposed specific conceptions of reality. Ancient philosophy was influential in the formation of Christian theology. For example, the opening of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the word and the word was with God…,” is unmistakably based on the idea of the “logos” going back to the philosophy of Heraclitus (ca. 535 – 475 BCE). Christian apologists like Justin Martyr writing in the second century understood Christ as the Logos or the Word of God who served as an intermediary between God and the World.

Early representations of Christ and the apostles

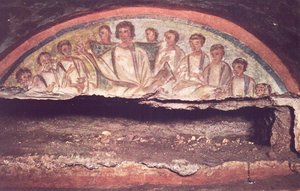

An early representation of Christ found in the Catacomb of Domitilla shows the figure of Christ flanked by a group of his disciples or students (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Those experienced with later Christian imagery might mistake this for an image of the Last Supper, but instead this image does not tell any story. It conveys rather the idea that Christ is the true teacher.

Christ draped in classical garb holds a scroll in his left hand while his right hand is outstretched in the so-called ad locutio gesture, or the gesture of the orator. The dress, scroll, and gesture all establish the authority of Christ, who is placed in the center of his disciples. Christ is thus treated like the philosopher surrounded by his students or disciples.

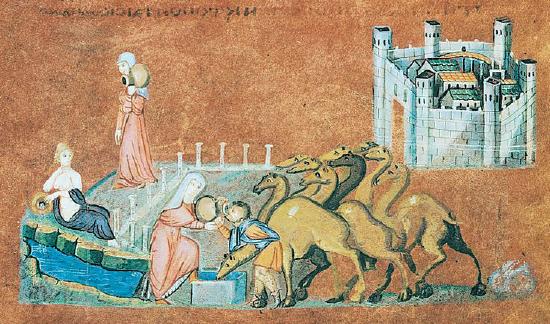

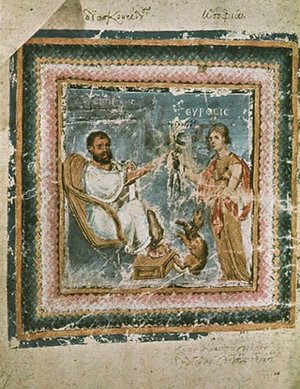

Books circulate easily because they are small and portable. Monks and nuns in monasteries often copied and illustrated Bibles, linking classical traditions such as classical manuscripts, which have been lost, and later illuminated manuscripts. As Dr. Nancy Ross notes, the artist who made the Vienna Genesis seems to be working between two systems and styles—one stemming from the ancient world and valuing naturalistic details and one stemming from a medieval preference for “valued symbolism and abstraction.” The book was believed to have been made in Syria or Constantinople, making the Vienna Genesis not only a luxury item, and a bit of a time capsule capturing this transitional time, but also a real global commodity due to the ways in which the artist integrated multiple styles in the visual representations.

The story of Rebecca and Eliezer comes from Genesis, and as Ross summarizes, is a story “about God intervening to ensure a sound marriage for Abraham’s son.” The artist employs a continuous narrative, showing two consecutive scenes simultaneously. Here, the artist suggests time passing by including Rebecca twice in the story, in the same pink dress (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)). In just this one image from the codex, which is estimated to have originally included 192 illustrations, the artist includes stylistic details that not only nod to classical architecture and sculptural poses, but embrace Early Christian art, with its emphasis on symbolism over a preoccupation with accurate or detailed spatial representation.

Dura-Europos

The origins of Byzantine Architecture: Buildings for a Minority Religion

by Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

Officially Byzantine architecture begins with Constantine, but the seeds for its development were sown at least a century before the Edict of Milan granted toleration to Christianity in 313 CE. Although limited physical evidence survives, a combination of archaeology and texts may help us to understand the formation of an architecture in service of the new religion.

The domus ecclesiae, or house-church, most often represented an adaptation of an existing Late Antique residence to include a meeting hall and perhaps a baptistery. Most examples are known from texts; while there are significant remains in Rome, where they were known as tituli, most early sites of Christian worship were subsequently rebuilt and enlarged to give them a suitably public character, thus destroying much of the physical evidence.

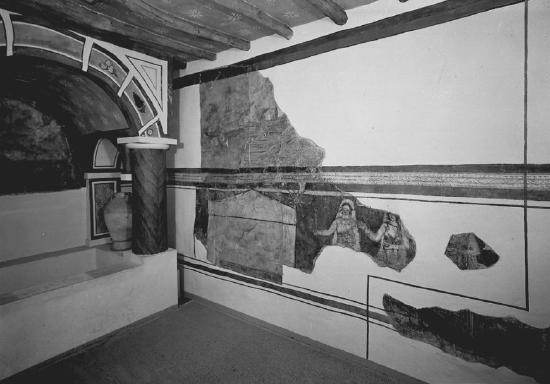

Synagogues and mithraia from the period are considerably better preserved. A notable exception is the Christian House at Dura-Europos in Syria, built c. 200 on a typical courtyard plan. Modified c. 230, two rooms were joined to form a longitudinal meeting hall; another was provided with a piscina (a basin for water) to function as a baptistery for Christian initiation (see Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) to see a reconstruction of the Baptistery).

Dura-Europos

Dura-Europos, a border city between the Romans and the Parthians, was the site of an early Jewish synagogue dated by an Aramaic inscription to 244 CE. It is also the site of Christian churches and mithraea, this city’s location between empires made it an optimal spot for cultural and religious diversity.

The synagogue is the best preserved of the many imperial Roman-era synagogues that have been uncovered by archaeologists. It contains a forecourt and house of assembly with frescoed walls depicting people and animals, as well as a Torah shrine in the western wall facing Jerusalem.

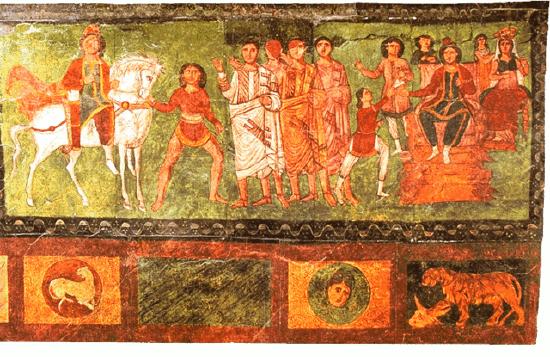

The synagogue paintings, the earliest continuous surviving biblical narrative cycle, are conserved at Damascus, together with the complete Roman horse armor. Because of the paintings adorning the walls, the synagogue was at first mistaken for a Greek temple. The synagogue was preserved, ironically, when it was filled with earth to strengthen the city’s fortifications against a Sassanian assault in 256 CE.

The preserved frescoes include scenes such as the Sacrifice of Isaac and other Genesis stories, Moses receiving the Tablets of the Law, Moses leading the Hebrews out of Egypt, scenes from the Book of Esther (see Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)), and many others. The Hand of God motif is used to represent divine intervention or approval in several paintings. Scholars cannot agree on the subjects of some scenes, because of damage, or the lack of comparative examples; some think the paintings were used as an instructional display to educate and teach the history and laws of the religion.

Others think that this synagogue was painted in order to compete with the many other religions being practiced in Dura-Europos. The new (and considerably smaller) Christian church (Dura-Europos church) appears to have opened shortly before the surviving paintings were begun in the synagogue. The discovery of the synagogue helps to dispel narrow interpretations of Judaism’s historical prohibition of visual images.

Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus

by Dr. Allen Farber

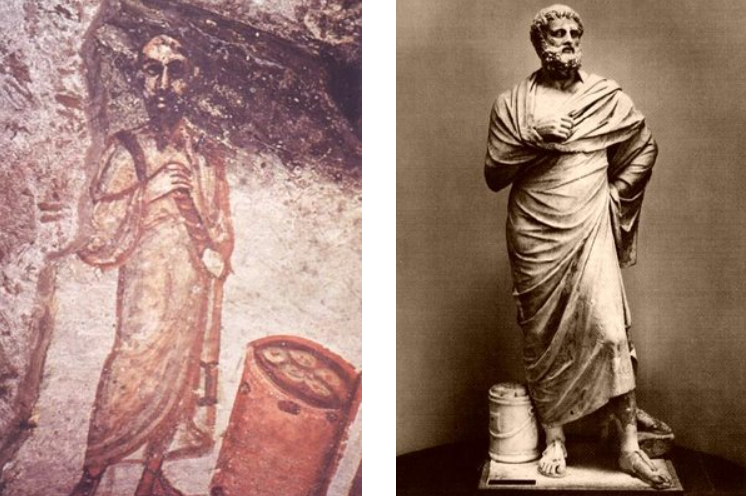

Early Christian and Roman (pagan) art

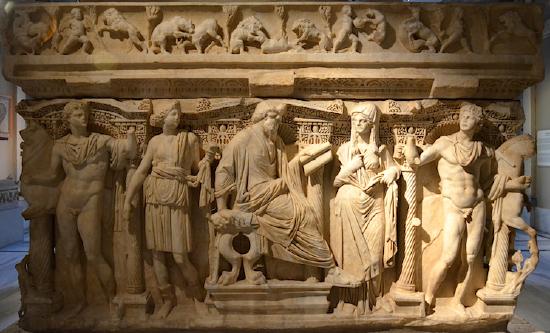

This third century sarcophagus from the Church of Santa Maria was undoubtedly made to serve as the tomb of a relatively prosperous third century Christian. As we will see in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\), Early Christian art borrowed many forms from pagan art.

The male philosopher type that we see in the center of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)) is easily identifiable with the same type in another third century sarcophagus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)), but in this case a non-Christian one.

The female figure beside him in the Santa Maria Antiqua sarcophagus who holds her arms outstretched combines two different conventions. The outstretched hands in Early Christian art represent the so-called “orant” or praying figure (see Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)). This is the same gesture found in the catacomb paintings of Jonah being vomited from the great fish, the Hebrews in the Furnace, and Daniel in the Lions den.

The juxtaposition of this female figure with the philosopher figure associates her with the convention of the muse in ancient Greek and Roman art (as a source of inspiration for the philosopher). This convention is illustrated in a later sixth century miniature showing the figure of Dioscorides, an ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist (see Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\)).

On the left side of the sarcophagus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)), Jonah is represented sleeping under the ivy after being vomited from the great fish. The pose of the reclining Jonah with his arm over his head is based on the mythological figure of Endymion, whose wish to sleep for ever—and thus become ageless and immortal—explains the popularity of this subject on non-Christian sarcophagi (see the detail from a Roman sarcophagus in Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)).

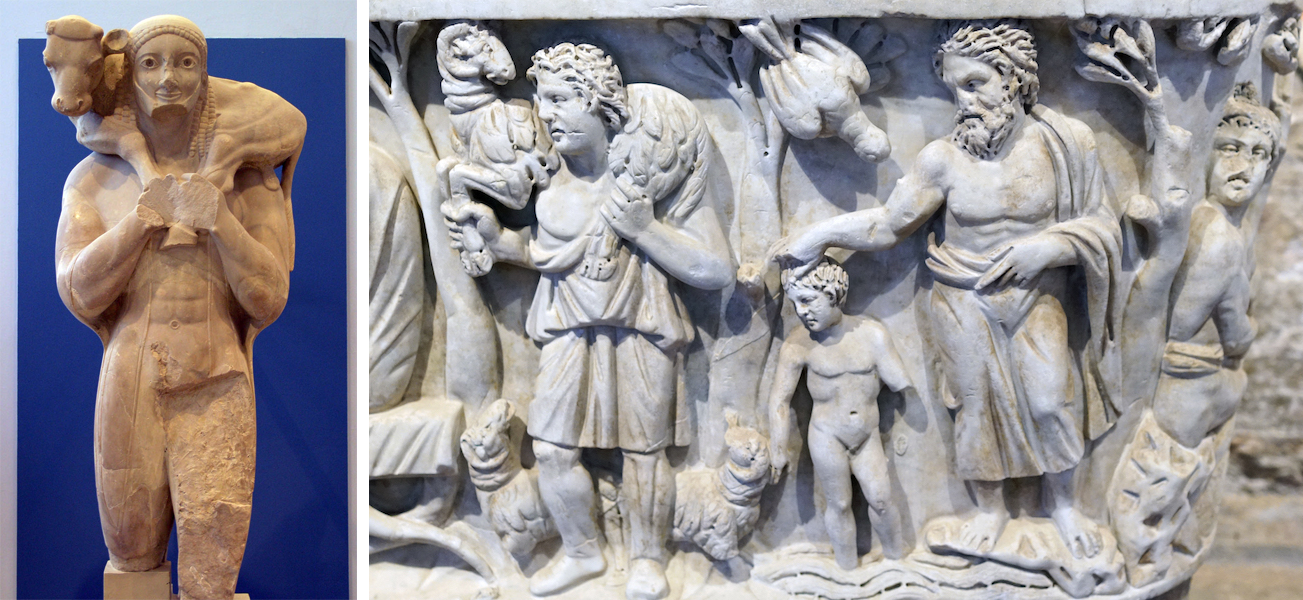

Another popular Early Christian image appears on the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\), right), known as the Good Shepherd. While echoing the New Testament parable of the Good Shepherd and the Psalms of David, the motif had clear parallels in Greek and Roman art, going back at least to Archaic Greek art, as exemplified by the so-called Moschophoros, or calf-bearer, from the early sixth century BCE (see Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\), left). On the far right of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus, we see an image of the Baptism of Christ. The inclusion of this relatively rare representation of Christ probably refers to the importance of the sacrament of Baptism, which signified death and rebirth into a new Christian life.

A curious detail about the male and female figures at the center of the Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus is that their faces are unfinished (see Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\)). This suggests that this tomb was not made with a specific patron in mind. Rather, it was fabricated on a speculative basis, with the expectation that a patron would buy it and have his—and presumably his wife’s—likenesses added. If this is true, it says a lot about the nature of the art industry and the status of Christianity at this period. To produce a sarcophagus like this meant a serious commitment on the part of the maker. The expense of the stone and the time taken to carve it were considerable. A craftsman would not have made a commitment like this without a sense of certainty that someone would purchase it.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Nancy Ross, "Christianity, an introduction," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Allen Farber, "Early Christianity, an introduction," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Allen Farber, "Early Christian art," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, "The origins of Byzantine architecture," in Smarthistory, June 8, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)