12.3: Christian Art and Architecture After Constantine

- Page ID

- 108672

Early Christian art and architecture after Constantine

by Dr. Allen Farber

By the beginning of the fourth century Christianity was a growing mystery religion in the cities of the Roman world. It was attracting converts from different social levels. Christian theology and art was enriched through the cultural interaction with the Greco-Roman world. But Christianity would be radically transformed through the actions of a single man.

Rome becomes Christian and Constantine builds churches

In 312, the Emperor Constantine defeated his principal rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Accounts of the battle describe how Constantine saw a sign in the heavens portending his victory. Eusebius, Constantine’s principal biographer, describes the sign as the Chi Rho, the first two letters in the Greek spelling of the name Christos.

After that victory Constantine became the principal patron of Christianity. In 313 he issued the Edict of Milan which granted religious toleration. Although Christianity would not become the official religion of Rome until the end of the fourth century, Constantine’s imperial sanction of Christianity transformed its status and nature. Neither imperial Rome or Christianity would be the same after this moment. Rome would become Christian, and Christianity would take on the aura of imperial Rome.

The transformation of Christianity is dramatically evident in a comparison between the architecture of the pre-Constantinian church and that of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian church. During the pre-Constantinian period, there was not much that distinguished the Christian churches from typical domestic architecture. A striking example of this is presented by a Christian community house, from the Syrian town of Dura-Europos. Here a typical home has been adapted to the needs of the congregation. A wall was taken down to combine two rooms: this was undoubtedly the room for services. It is significant that the most elaborate aspect of the house is the room designed as a baptistry. This reflects the importance of the sacrament of Baptism to initiate new members into the mysteries of the faith. Otherwise this building would not stand out from the other houses. This domestic architecture obviously would not meet the needs of Constantine’s architects.

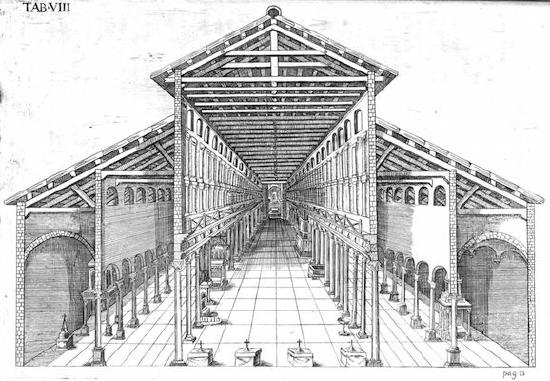

Emperors for centuries had been responsible for the construction of temples throughout the Roman Empire. We have already observed the role of the public cults in defining one’s civic identity, and Emperors understood the construction of temples as testament to their pietas, or respect for the customary religious practices and traditions. So it was natural for Constantine to want to construct edifices in honor of Christianity. He built churches in Rome including the Church of St. Peter (see a rendering of Old St. Peter's Basilica in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), he built churches in the Holy Land, most notably the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, and he built churches in his newly-constructed capital of Constantinople.

The basilica

In creating these churches, Constantine and his architects confronted a major challenge: what should be the physical form of the church? Clearly the traditional form of the Roman temple would be inappropriate both from associations with pagan cults but also from the difference in function. Temples served as treasuries and dwellings for the cult; sacrifices occurred on outdoor altars with the temple as a backdrop. This meant that Roman temple architecture was largely an architecture of the exterior. Since Christianity was a mystery religion that demanded initiation to participate in religious practices, Christian architecture put greater emphasis on the interior. The Christian churches needed large interior spaces to house the growing congregations and to mark the clear separation of the faithful from the unfaithful. At the same time, the new Christian churches needed to be visually meaningful. The buildings needed to convey the new authority of Christianity. These factors were instrumental in the formulation during the Constantinian period of an architectural form that would become the core of Christian architecture to our own time: the Christian Basilica.

The basilica was not a new architectural form. The Romans had been building basilicas in their cities and as part of palace complexes for centuries. A particularly lavish one was the so-called Basilica Ulpia constructed as part of the Forum of the Emperor Trajan in the early second century (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Basilicas had diverse functions but essentially they served as formal public meeting places. One of the major functions of the basilicas was as a site for law courts. These were housed in an architectural form known as the apse. In the Basilica Ulpia, these semi-circular forms project from either end of the building, but in some cases, the apses would project off of the length of the building. The magistrate who served as the representative of the authority of the Emperor would sit in a formal throne in the apse and issue his judgments. This function gave an aura of political authority to the basilicas.

The basilica at Trier (Aula Palatina)

Basilicas also served as audience halls as a part of imperial palaces. A well-preserved example is found in the northern German town of Trier. Constantine built a basilica as part of a palace complex in Trier which served as his northern capital (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Although a fairly simple architectural form and now stripped of its original interior decoration, the basilica must have been an imposing stage for the emperor. Imagine the emperor dressed in imperial regalia marching up the central axis as he makes his dramatic adventus or entrance along with other members of his court. This space would have humbled an emissary who approached the enthroned emperor seated in the apse.

The wide central aisle is called a nave, from the Latin word for ship. Indeed, the rafters of a ceiling like Old St. Peter’s, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), would look like the ribs of an inverted ship hull. Both Old St. Peter’s Basilica and the Aula Palatina have a longitudinal plan, meaning they’re arranged along a single central axis, here culminating at the altar. This is intentionally different from the central plan of pagan temples like the Pantheon.

Aksum was a prosperous cosmopolitan trading hub and early Christian state, located in present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea on the northeastern side of the African continent. This trading empire had a port city, Adulis, and connections to trade routes through the Red Sea, the Nile, and into the Indian Ocean. This kingdom was active between the first through eighth centuries, developing large-scale architecture and urban centers, both of which were greatly impacted by hybrid cultural influences from Arabic, Hellenic, and African empires and cultures, such as Egypt, Arabia, and the eastern Mediterranean.

In the first century CE, an Alexandria-based trader documented Aksum’s thriving and expanding reputation in international trade in his book Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Although lesser known to historians now, Aksum held great power and influence, particularly during the fourth and fifth centuries, considered the height of its power. Beyond its recognition as a bustling urban center and reputation for international commerce, Aksum is also known for its monumental monolithic stelae, its association with the Ark of the Covenant, its unique coinage, and its complex written script, Ge’ez.

Between 330-340, Aksum King Ezana converted to Christianity, making Aksum one of the earliest Christian states. To mark Aksum’s transition from a polytheist state to a Christian one (and to emphasize the importance of this conversion), King Ezana replaced existing imagery on his coins with a Christian cross. Aksumite coins were believed to be intended for international trade, reinforced by the Greek inscriptions on some and Ge’ez inscriptions on others.

As the British Museum asserts, “Aksum provides a counterpoint to the Greek and Roman worlds, and is an interesting example of a sub-Saharan civilization flourishing towards the end of the period of the great Mediterranean empires. It provides a link between the trading systems of the Mediterranean and the Asiatic world, and shows the extent of international commerce at that time… It was arguably as advanced as the Western European societies of the time.”

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Allen Farber, "Early Christian art and architecture after Constantine," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)