12.1: Late Antiquity and the Dissolution of the Roman Empire

- Page ID

- 108670

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Classicism and the Early Middle Ages

by Dr. Diana Reilly

In 1942 a farmer plowing a field in the East of England unearthed a substantial hoard of Roman silver dating from the fourth century, C.E. This became known as the “Mildenhall Treasure,” named for the nearby town. Its original owner may have buried his collection of banqueting vessels when the Roman administration left England in 410 C.E., hoping that he could later retrieve it. Among the spoons, bowls, dishes, and ladles is a two-foot wide silver platter weighing almost eighteen pounds, with classical motifs borrowed from antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome). However, though the platter depicts the gods Neptune and Bacchus, the owner was likely a follower of Christianity—a newly-sanctioned religion that was not yet the dominant belief system in Europe. This confluence of classical and Christian concepts is typical of the early middle ages. Because of the political and social upheavals happening in Europe at this time, the art of this period comprises a wide range of styles and themes that often blend classical elements with new and different ones.

A “decline”?

The transition between antiquity and the Middle Ages is often perceived as having been marked by a sharp break in beliefs and artistic style. This change was, in the past, characterized by scholars as a “decline.” According to this narrative, the chaotic and unstable atmosphere of the Roman Empire in the later third century led many of its inhabitants to embrace new, minority religions imported from the empire’s edges. Some of these were messianic religions that promised members an afterlife more pleasant than their current, increasingly difficult existences. At the same time, the economic struggles of the Late Roman Empire undermined investment in the artists’ workshops where the naturalism of classical Roman art had been taught to generations of artists. Lacking the traditional training, means, and patrons who valued classicism, artists during this period often worked in a more static, two-dimensional style that emphasized ideas and symbols over naturalistic illusionism. The abandonment of naturalistic style also coincided, it seemed, with the rise of a new majority religion, Christianity, that rejected materiality and traditional forms of beauty in favor of simplicity and self-denial.

Two stone reliefs installed on the Arch of Constantine demonstrate this supposed “decline.” The reused roundel with a sacrifice to Apollo (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) on left) originally carved for a monument to the Emperor Trajan between 117 and 138 (when the Roman empire was more stable), displays many key characteristics of classicism: varied depth of relief, carefully delineated drapery folds, and figures shifting in space. By contrast, in the panel depicting the emperor distributing largesse (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) on right), commissioned in the Late Empire between 312 and 315, the figures seem almost comically disproportionate, with enormous heads and hands, and draperies indicated by drilled lines.

The problem with the idea of a “decline” is that it ignores the many, often contradictory, currents of art and experience that existed in the late antique world. Romans had long sought to incorporate newly conquered and colonized populations by appropriating local religious beliefs and artistic traditions, in the process creating new, localized versions of Roman art that were sometimes less naturalistic. Even artists working in the capital, Rome, could choose to employ either naturalism or a more symbolic visual shorthand, depending on who made the art and who consumed it—as in the Amiternum Tomb (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), which was made during the first century, when classicism was the most prominent style. Instead of displaying a classical attention to composition, the artist has arrayed stocky figures of a variety of sizes in a seemingly haphazard way—going against the current artistic trends of the day.

Classicism survives

If works like the Amiternum Tomb help complicate the idea of an artistic decline, do they perhaps simply demonstrate variances in artists’ and patrons’ tastes? Some have argued that Emperor Constantine (who decriminalized Christianity in Rome in the early fourth century), and by extension the increasingly Christian populace, were, because of their beliefs, drawn to a non-classical style that denied naturalism in favor of a more symbolic set of forms. But surviving artworks commissioned by wealthy Romans show that, like their pagan peers, many Christians often still preferred a classicizing style—even if the subjects portrayed were new. For instance, in the middle of the fourth century the body of Junius Bassus, a Roman prefect, or high official, was buried in an elaborate marble sarcophagus.

Since he was a Christian convert, Junius’s sarcophagus was covered with narrative and symbolic scenes from the Christian bible, all rendered in a classicizing style (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) . The standing apostles are wrapped in Roman togas and the youthful Christ sits on a sella curulis, the animal-headed and -footed chair of the governing classes. Unlike most classical works, here the hands and heads of the figures are a little too large, but the artist was clearly attempting to employ the stylistic language of classicism to transmit Christian content.

These aesthetic departures from strict classicism were not limited to Christian-sponsored art: the same tendencies are apparent in objects that were commissioned by avowed pagans around the same time. This ivory panel was commissioned to celebrate a marriage between members of two Roman patrician (noble) families, the Nicomachi and Symmachi (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). A female figure with an oversized head and hands stands next to an altar, while a comparatively tiny servant stands behind it. The woman’s back leg projects in front of the surrounding frame, while her front leg, counterintuitively, stands on the ground within it, breaking the rules of naturalism. Based on the artworks that survive, we know that both pagan and Christian patrons found these kinds of contradictions in space and proportion acceptable.

A hoard of silver

There were also a diversity of themes preferred amongst patrons of different religions. Artworks from this time sometimes combine overtly pagan content with classicizing style, but for use by Christians. The so-called “Great Dish” found in the Mildenhall treasure is a shining example of such artistic combinations. Concentric rings of repoussé and engraved decoration celebrate the classical themes of the ocean and Bacchic revelry. The hair and beard of the Roman god Neptune in the center of the dish (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)) radiate dolphins and seaweed. Around him nymphs ride sea creatures.

In the outer band Bacchus (the god of wine), Hercules, Pan and throngs of satyrs and maenads holding Bacchic thistle-headed staffs and a shepherd’s crook twist and turn, draperies swirling, dancing with wine-induced abandon.

While this dish’s classicizing style and subject matter are undeniable, we known that its owner was likely Christian, as spoons from his dinnerware set (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) include the Christian symbols of the Chi-Rho and Alpha and Omega. Despite his Christianity, the owner likely felt perfectly comfortable displaying the platter with its exuberant dancing nudes on his sideboard for the admiration of his guests.

Rather than demonstrating a “decline” or a sharp break in artistic themes and styles, Roman artworks of the early middle ages display as much diversity and blending as the empire itself.

Decline of the Roman Empire

by Lumen Learning

The Tetrarchy

Emperor Diocletian institutionalized the Tetrarchy, a co-rule that re-established stability in the empire for the period of Diocletian’s reign. Diocletian, a military general from the cavalry, was declared emperor by his legion in 284 CE. He re-established stability in the empire and paved the way for fourth-century political and social developments. Diocletian achieved stability by establishing the Tetrarchy, Greek for rule by four. The Tetrarchy consisted of four emperors who reigned over two halves of the empire. Each pair of emperors was given control over either the eastern or western portion of the empire. Of the pair, one was given the title Caesar (a junior emperor) and the other Augustus (the senior emperor). This allowed Diocletian and his fellow emperors to organize the administration of the provinces, separate military and civic command, and restore authority throughout the realm. They further solidified their commitment to each other and communal rule by marrying into each other’s families.

Portraits of the Tetrarchs

Imperial portraiture of the Tetrarchs depicts the four emperors together and looking nearly identical. The portraiture symbolizes the concept of co-rule and cohesiveness instead of the power of the individual. The idea of the Tetrarchy, which is apparent in their portraits, is based on the ideal of four men working together to establish peace and stability throughout the empire.

The medium of the famous porphyry sculpture of the Tetrarchs, originally from the city of Constantinople, represents the permanence of the emperors. Furthermore, the two pairs of rulers—a Caesar and an Augustus with arms around each other— form a solid, stable block that reinforces the stability the Tetrarchy brought to the Roman Empire.

Stylistically, this portrait of the Tetrarchs is done in Late Antique style, which uses a distinct squat, formless bodies, square heads, and stylized clothing clearly seen in all four men. The Tetrarchs have almost no body.

As opposed to Classical sculptures, which acknowledge the body beneath the attire, the clothes of the Tetrarchs form their bodies into chunky rectangles. Details such as the cuirass (breastplate), skirt, armor, and cloak are highly stylized and based on simple shapes and the repetition of lines. Despite the culmination of this artistic style, the rendering of the Tetrarchs in this manner seems to fit the connotations of Tetrarch rule and need for stability throughout the empire.

The Arch of Constantine

The Arch of Constantine demonstrates the continuance of the newly-adopted artistic style for imperial sculpture. This arch was erected between the Colosseum and Palatine Hill, the home of the imperial palace. It stands over the triumphal route before it enters the Republican Forum. This forms a dialog with the Arch of Titus at the top, overlooking the Forum, and the Arch of Septimius Severus, which, in turn, stands at the other end of the Forum before the Via Sacra heads uphill to the Capitolium. The Senate commissioned the triumphal arch in honor of Constantine’s victory over Maxentius. It is a triple arch and its iconography represents Constantine’s supreme power and the stability and peace his reign brought to Rome.

The Arch of Constantine is especially noted for its use of spolia: architectural and decorative elements removed from one monument for use on another. Those from the monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius—all considered good emperors of the Pax Romana—were reused as decoration. Trajanic panels that depict the emperor on horseback defeating barbarian soldiers adorn the interior of the central arch. The original face was reworked to take the likeness of Constantine. Eight roundels, or relief discs, adorn the space just above the two smaller side arches. These are Hadrianic and depict images of hunting and sacrifice. The final set of spolia includes eight panel reliefs on the arch’s attic, from the era of Marcus Aurelius, depicting the dual identities of the emperor, as both a military and a civic leader. The incorporation of these elements symbolize Constantine’s legitimacy and his status as one of the good emperors.

The rest of the arch is decorated using Late Antique styles. The proximity of different artistic styles, under four different emperors, highlights the stylistic variations and artistic developments that occurred, both in the second century CE, as well as their differences to the Late Antique style. Besides the decorative elements in the spandrels, a Constantinian frieze runs around the arch, between the tops of the small arches and the bottoms of the roundels. The frieze in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\ highlights the artistic style of the period and chronologically depicts Constantine’s rise to power. Unlike previous examples of Late Antique art, the bodies in this frieze are completely schematic and defined only by stiff, rigid clothes. In one scene, featuring Constantine distributing gifts, the emperor is centrally depicted and raised above his supporters on a throne.

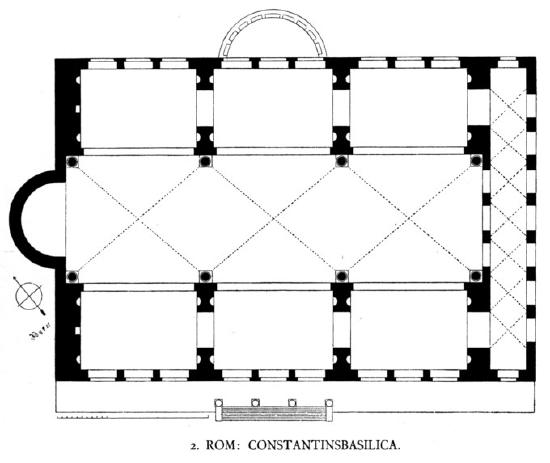

Basilica Nova and the Colossus of Constantine

When Constantine and Maxentius clashed at the Milvian Bridge, Maxentius was in the middle of building a grand basilica. It was eventually renamed the Basilica Nova, and was located near the Roman Forum. The basilica consisted of one side aisle on either side of a central nave (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)).

When Constantine took over and completed the grand building, it was 300 feet long, 215 feet wide, and stood 115 feet tall down the nave. Concrete walls 15 feet thick supported the basilica’s massive scale and expansive vaults (see Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)). It was lavishly decorated with marble veneer and stucco. The southern end of the basilica was flanked by a porch, with an apse at the northern end.

The apse of the Basilica Nova was the location of the Colossus of Constantine. The colossus in Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) was built from many parts. The head, arms, hands, legs, and feet were carved from marble, while the body was built with a brick core and wooden framework and then gilded.

Only parts of the Colossus remain, including the head that is over eight feet tall and 6.5 feet long. It shows a portrait of an individual with clearly defined features: a hooked nose, prominent jaw, and large eyes that look upwards. Like the porphyry bust of Galerius, Constantine’s portrait combines naturalism in his nose, mouth, and chin with a growing sense of abstraction in his eyes and geometric hairstyle.

He also held an orb and, possibly, a scepter, and one hand points upwards towards the heavens. Both the immensity of the scale and his depiction as Jupiter (seated, heroic, and semi-nude) inspire a feeling of awe and overwhelming power and authority.

The basilica was a common Roman building and functioned as a multipurpose space for law courts, senate meetings, and business transactions. The form was appropriated for Christian worship and most churches, even today, still maintain this basic shape.

Diocletian's Palace at Split

Diocletian abdicated power in 305 CE and left the Tetrarchy to his co-emperors and Severus, the newly inaugurated general. Diocletian then retired to his boyhood palace in Dalmatia.

The palace’s remains became the center of the modern city of Spilt in Croatia. Diocletian’s palace was built as a fortress, demonstrating that despite Diocletian’s success as emperor, he still required security living in a hostile Roman environment. Despite the stylistic changes in sculpture, Diocletian’s palace serves as a reminder that the style of Roman architecture continued to be based on Classical models and forms.

In addition to its numerous round arches and Classical columns, the palace also contains a vestibule with a domed ceiling that has an oculus somewhat reminiscent of the Pantheon in Rome (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). The palace was set up in a similar fashion to a castrum and contained courts, libraries, and other features found in imperial villas. It was constructed from local materials including limestone, marble, and brick. Some material for decoration was imported: Egyptian granite columns, fine marble for revetments, and some capitals produced in workshops in the Proconnesos (present-day Marmara Island off the coast of Turkey).

The southern wall, which was the only unfortified part of the palace, was practically built on the waterfront and appeared to rise out of the Adriatic Sea. Diocletian’s palace demonstrates the Roman use of vaults in the substructure and the use of columns, peristyles, and entablatures to create monumental spaces. For example, the central court of the palace, known as the Peristyle, demonstrates the stylistic and monumental use of these architectural elements. Furthermore, the central court was sunken and a flight of stairs enclosed the court and led up to the decorative Peristyle and surrounding rooms (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). This increased the feeling of monumentality while emphasizing Diocletian’s imperial power, as members of the court had to stand several steps below the entrances to the temples, mausoleum, and court rooms.

A main feature of the Peristyle is the portico that marks the entrance to Diocletian’s private apartments. Following the format of a traditional Roman temple to a degree, the portico rests atop a raised platform. Behind it rests a marble-faced brick wall with three entrances: an archway flanked by a rectangular portal on each side. Perhaps its most unique feature is the arcuated pediment that sits atop the temple facade. Resting on four Composite columns, the pediment contains a round arch that rises into its base toward its apex. An arcade supported by Composite columns stands to either side of the facade.

The northern half of the palace, divided in two parts by the cardo leading from the northern gate to the Peristyle, is not as well preserved as the rest of the palace. Scholars posit that each part was a residential complex that housed soldiers, servants, and possibly some other facilities. Both parts were apparently surrounded by streets. Leading to the perimeter walls there were rectangular buildings that were possibly storage magazines.

While the architectural aspects of the palace follow Roman traditions, several decorative choices hail from Egypt. Diocletian adorned his new home with numerous 3500-year-old granite sphinxes, originating from the site of Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III (see Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\)). Only three have survived the centuries. One is still on the Peristyle, the second sits headless in front of Jupiter’s temple, and a third is in the city museum.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Diane Reilly, "Classicism and the Early Middle Ages," in Smarthistory, June 12, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Lumen Learning, “Decline of the Roman Empire,” Lumen Learning (CC BY 4.0)