12.0: Chapter Introduction

- Page ID

- 180552

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction: The Roman Empire under Pressure

At opposite ends of the outer reaches of the Roman Empire, two accidental time capsules were buried, not to be rediscovered for centuries. The first, in what is today Syria, was an entire section of the town of Dura-Europos (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The second, approximately 3,000 miles away in what is today England, was a stash of ornate silver tableware. Both locations were at the borders of an empire that was under pressure: Dura-Europos from the massive Sassanian Persian army to the east, and Mildenhall, England, about a century later, from raiding northern tribes. Eventually, the Roman Empire would shrink and fragment under the repeated attacks from all sides, but before that, the style and techniques of the Classical world would both persist and morph as the empire incorporated citizens from other cultures and religions. Dura-Europos and the Mildenhall Treasure both show not only the persistent influence of Classical Rome, but also an increasing number of different belief systems and traditions within the vast empire.

A Buried Street

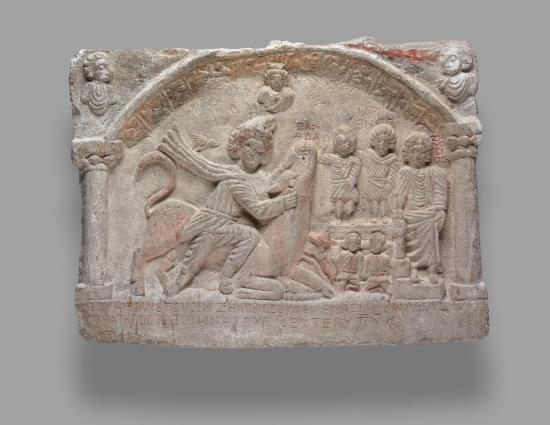

Dura-Europos was a Roman garrison town on the Euphrates River. In 256 CE, preparing to defend the city against the Sassanian Persian army, the Romans reinforced its western wall by burying the street at its base, including temples, homes, a mithraeum, a Jewish synagogue and a Christian house-church. Even with its newly-fortified wall, however, Dura-Europos was no match for the Sassanian siege. Soon after taking Dura-Europos, the Persians abandoned it and shifting sand and mud buried it. When it was excavated in the 20th century, archaeologists discovered evidence of a remarkably cosmopolitan and pluralistic society, documented in art from brilliantly-preserved frescoes to sculptures. A Jewish house of worship, or synagogue, was decorated in scenes from Jewish scriptures, in which figures wear Roman togas as well as Persian-style trousers. In a relief carving in a nearby Mithraeum, a place to worship the Persian deity Mithras, Mithras appears in his usual dress—the shirred trousers, long sleeves, flaring tunic and (probably) the floppy Phrigian hat seen on Persian rulers, while other figures wear Roman garb (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). And on the same street, a Christian house-church featured a tank for baptism, underneath a painting of a figure holding an animal across his shoulders: Christ as the Good Shepherd (a motif borrowed from Classical depictions of Apollo).

A Buried Treasure

Across the Roman Empire, in fifth-century Britain, Classically-inspired figures graced the intricately decorated silver tableware of the Mildenhall Treasure, buried by a rich Roman who clearly intended to return for it once the raiding Celts and Picts had been subdued. Instead, a farmer plowing his field found it in 1942. The treasure included dozens of cups, spoons, and elaborately detailed plates. One particularly striking platter (known as the “Great Dish”), measuring nearly two feet wide and weighing more than 18 pounds, features deities and figures from Classical mythology, skillfully wrought in elegant repoussé (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). As Dr. Diane Reilly writes later in this chapter, despite this blatantly pagan imagery, the owner might have been Christian, as three silver spoons refer to Christ with Greek letters: chi and rho, the first two letters of “Christos” (Christ); and alpha and omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet and a reference to “the Lord” calling himself the “alpha and omega.”The figures on the Great Dish have elegant proportions, but like those portrayed in the Dura-Europos synagogue frescoes, lack the carefully-observed naturalism of Classical Greek and Roman sculpture and painting.

Both Dura-Europos and the Mildenhall Treasure show an empire undergoing change and shaped by powerful influences: the neighbors pressing at its increasingly-thinly-stretched borders, the exchange of ideas between a culturally vast/divergent empire, and the rising influence of Christianity and other mystery religions.

Historiography (Writing History)

The Role of Christianity

Among the religions active in Late Antiquity, Christianity is often given special attention, to the extent of treating the whole period as Early Christian. Since so much of European art history has focused on Christian art, its roots have seemed particularly important. Remember, however, that Christianity was only one among many of the non-Greco-Roman religions found in Late Antiquity. Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, adaptations of Egyptian cults, and Judaism all have left artistic traces as interesting as the art of Christianity before its official recognition.

Although migrations of new peoples into the Roman Empire profoundly affected Late Antique culture, the art of these peoples can also be considered medieval, as important contributions to the art of Western European Christians, who adopted elements of their non-Roman predecessors. The next chapter, on Early Medieval art, will include art by the Vikings, Saxons, and Lombards, looking at how so-called “barbarian” and “pagan” art forms shaped Christian sculpture and manuscript illumination.

Terminology

Late Antiquity

Calling this period Late Antiquity stresses that while many norms of Greco-Roman culture persisted, something new was replacing them. In a blockbuster exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum called this period “The Age of Spirituality,” acknowledging the increased role of the mystery religions, including Christianity. Many objects and buildings show an increased interest in the ethereal, often denying the physical human body or even the structure of buildings. Often people look like expanses of drapery from which heads, hands, and feet protrude. Buildings feature seemingly impossible vaults, or expanses of flat wall that look impossibly thin. Even images that evoke Classical naturalism, like the Symmachi diptych panel discussed later in this chapter, ignore basic rules of Classical representation, as where the woman’s back foot breaks the frame of the image.

Periodization

These stylistic and cultural changes rarely took place in a linear manner; some seem sudden, some gradual, and some sporadic. There are no exact dates for Late Antiquity. This chapter deals with developments in the Roman Empire between the end of the Severan dynasty in 230 CE and the relocation of the East Roman capital to Constantinople in 333 CE, but extends later into western Europe during the more gradual establishment of Christianity there. Some would classify parts of this as Late Roman; others as “Early Medieval.” Late Antique spans both categories.

Chapter Overview

This chapter examines art of Late Antiquity, centuries when the Roman Empire underwent massive changes, especially as it was increasingly beset by neighbors Romans called “barbarians”. This pejorative term comes from the Greek word, barbaros, which itself derives from what foreign languages sounded like to Greeks: “bar-bar-bar”.

Romans had long scorned these “barbarian” neighbors, enjoying depictions of them enslaved or dying (such as the Dying Gauls discussed in Chapter 9, found in Rome). Roman armies fought to conquer—or at least beat back—waves of these “barbarians.” In the Gallic wars (58-50 BCE), Julius Caesar fought Celts and Germanic tribes; by the fourth century the Romans were fighting against waves of Germanic peoples who were being pushed west into Roman territory by other groups to the east. Among those Germanic peoples were the Vandals and the Goths. However, Roman soldiers sent to protect the borders settled there, married, and adopted the dress, weaponry, and gods of these neighbors. As the empire recruited local men into the Roman army, their armies came to be composed of Germanic tribesmen; Goths battled Roman Vandals for control of Roman cities. A former Roman officer, the Visigoth Aleric, led his troops in the sack of the city of Rome itself in 410 CE.

The Roman Empire underwent massive changes during the third through fifth centuries. In an attempt to restore stability, the Emperor Diocletian divided the empire between four rulers and into two halves: east and west. Known as the tetrarchy, from the Greek word meaning the “rule of four,” this four-ruler plan worked well while Diocletian was alive, but often failed after his death. After a civil war, the Emperor Constantine emerged as the single ruler of a united, if diminished, Roman Empire, and moved his capital from Rome to Byzantium in the east, calling it “New Rome.”

An eastern/western split persists even today in the understanding of the late Roman and medieval Christian world. The eastern half spoke Greek, and is now called the Byzantine Empire (a modern term—they called themselves Romans). In particular, Constantine favored the previously-persecuted religion of Christianity, which became one of the major drivers of the art featured in this chapter and in the rest of the textbook. In the west, Latin was the language of the church and of some elites, but local languages predominated in a patchwork of small bands, kingdoms, or governments as they vied for supremacy, while missionaries and monks spread Christianity.

One of the characteristics of Late Antiquity is the sheer variety of works of art created during a time that saw the Roman Empire nearly fall apart amidst the struggle to create new ways of organizing communities. In terms of style, art of Late Antiquity is eclectic, and the types of objects included in this chapter range from silver and ivory works intended to connect to Hellenistic civilizations to blocky yet expressive images of emperors. The Greco-Roman Classical style often appears alongside an expressive style more concerned with geometry than with human anatomy, sometimes even on the same monument, such as the Arch of Constantine.

Objects overview

This chapter explores how very different societies adapted Greco-Roman traditions, with purposes as different as worshiping Mithras or Christ, celebrating the power of the emperor, and recalling the Greek god of wine, Bacchus, at a lavish dinner party. This chapter covers archaeological sites and well-preserved buildings as well as luxury portable objects, including:

- the Mildenhall Treasure, luxurious household objects buried for safekeeping in the face of barbarian raids on Roman Britain

- the Dura-Europos Synagogue and Christian house church, preserved because they were used to buttress the walls of a Roman city

- Diocletian’s Palace at Split, where the emperor deployed every technique of Roman architecture to create a secure retirement home well away from the city of Rome

- the Tetrarchy, a portrait of four men sharing imperial power, so abstract that none of them can be securely identified

- the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, one of the earliest high-quality objects clearly made for a Christian

- the Symmachi Diptych, an ivory panel with both Classical and anti-naturalistic elements

- the Basilica Nova and the Colossus of Constantine, an expression of imperial power designed to be overwhelming

- the Aula Palatina in Trier, a secular example of the basilican plan Constantine introduced for churches

By the time you finish reading this chapter on Late Antique art, you should be able to:

- Identify Classical and non-Classical elements in the art of Late Antiquity

- Describe different styles of art and cultures covered in art of Late Antiquity

- Discuss the impact of Constantine’s patronage on the spread of Christian art and architecture

Want to Know More?

Here are some additional resources you can explore to further your understanding of the art discussed in this chapter.

- The catalog for the Metropolitan Museum’s comprehensive exhibition on Late Antique art, The Age of Spirituality

- Yale University Art Gallery’s immersive site "Dura-Europos: Excavating Antiquity"

- Carly Silver, “Dura-Europos: Crossroad of Culture,” for Archaeology

- Mildenhall Treasure at the Mildenhall Museum

- The Mildenhall Great Dish at the British Museum

- Crash Course, “Christianity from Judaism to Constantine” [video]

- Steven Fine, "Writing a History of Jewish Architecture" for Smarthistory