4.2: Mesoamerica (Olmec, Teotihuacan, Maya)

- Page ID

- 108705

Defining “Pre-Columbian” and “Mesoamerica”

adapted from Dr. Maya Jiménez

What does “pre-Columbian” mean?

The original inhabitants of the Americas traveled across what is now known as the Bering Strait, a passage that connected the westernmost point of North America with the easternmost point of Asia. The Western hemisphere was disconnected from Asia at the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 BCE.

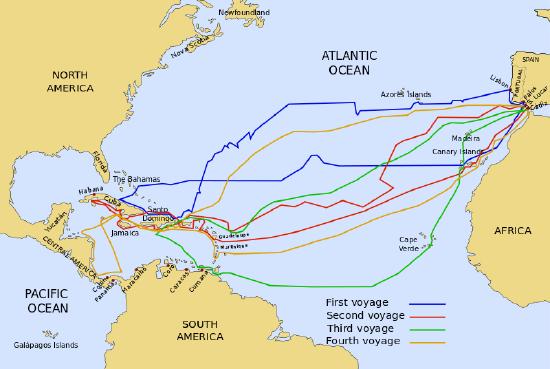

In 1492, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus arrived at the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic), mistakenly thinking he had reached Asia. Columbus’ miscalculation marked the first step in the colonization of the Americas, or what was then seen as a “New World.” Incorrectly referring to the native inhabitants of Hispaniola as “Indians” (under the assumption that he had landed in India), Columbus established the first Spanish colony of the Americas. “Pre-Columbian” thus refers to the period in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus.

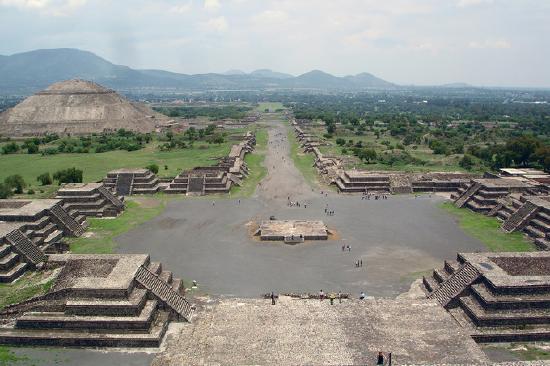

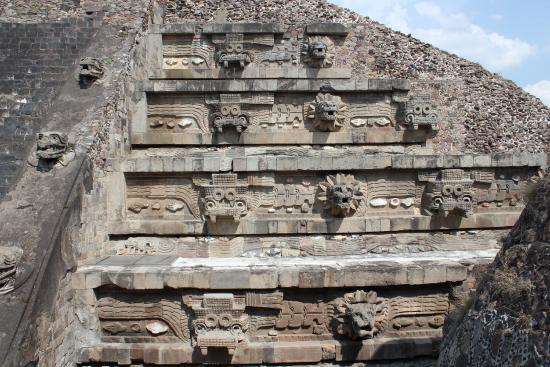

The Spanish conquistadores (conquerors) found that the “New World” was in fact not new at all, and that the indigenous people of Mesoamerica had established advanced civilizations with densely populated cities and towering architectural monuments such as at Teōtīhuacān (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), as well as advanced writing systems.

The term pre-Columbian is complicated however. For one thing, although it refers to the indigenous peoples of the Americas, the phrase does not directly reference any of the many sophisticated cultures that flourished in the Americas (think of the Aztec, Inka, or Maya, to name only a few) and instead invokes a European explorer. For this reason and because indigenous peoples flourished before and after the arrival of the Europeans, the term is often seen as flawed. Other terms such as pre-Hispanic, pre-Cortesian, or more simply, ancient Americas, are sometimes used.

What does “Mesoamerica” mean?

The region of Mesoamerica—which today includes central and south Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador—consists of a diverse geographic landscape of highlands, jungles, valleys, and coastlines. Mesoamericans did not exploit technological innovations such as the wheel—though they were used in toys— and did not develop metal tools or metalworking techniques until at least until 900 CE. Instead, Mesoamerican artists are known for producing megalithic (large stone) sculpture and extremely sharp weapons from obsidian (volcanic glass). Featherwork and stonework in basalt, turquoise, and jade dominated Mesoamerican artistic production, while exceptional textiles and metallurgy flourished further south, among pre-Columbian Andean and Central American cultures, respectively.

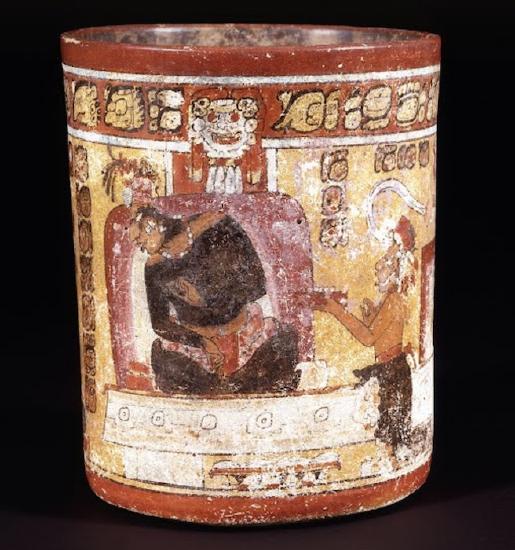

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures shared certain characteristics such as the ritual ballgame (illustrated in the drinking vessel in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)); pyramid building; human sacrifice; maize as an agricultural staple; and deities dedicated to natural forces (i.e. rain, storm, fire). Additionally, some Mesoamerican societies developed sophisticated systems of writing, as well as an advanced understanding of astronomy (which allowed for the development of accurate and complex calendar systems, including the 260-day sacred calendar and the 365-day agricultural calendar). As a result, cities like La Venta and Chichen Itza were aligned in relation to cardinal directions and had a sacred center. The fact that many of these cultural trademarks persisted for more than 2,000 years across civilizations as distinct as the Olmec (c. 1200–400 BCE) and the Aztec (c. 1345 to 1521 CE), demonstrates the strong cultural bond of Mesoamerican cultures.

The ballgame was played in different iterations at different times and in different places—and in fact, it is still played today in many Mesoamerican cultures. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains: “The game is played in modern times as well: in the 2017 Mesoamerican Ballgame Tournament, held in Teotihuacan, Mexico, the team from Belize took home the title.”

It was played with a rubber ball that players hit with their elbows, hips, or knees. The ballgame was considered an important ritual in Mesoamerica and was practiced first by the Olmec and last by the Aztec. Since the rubber ball was solid and heavy, players wore protective gear to avoid injury and may have tried to score the ball through a ring, which was usually located high on the wall of the ballcourt. Numerous rubber balls and ballcourts have been discovered throughout Mesoamerica in El Tajín (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) and Monte Albán, although the largest surviving ballcourt is located in Chichen Itza. While the ballgame was played by the elite, it was believed that the fate of the game and thus of the player was determined by the gods. As a result, the Mesoamerican ballgame held significant implications. Learn more about the ballgame here.

Mesoamerica, an introduction

by Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank

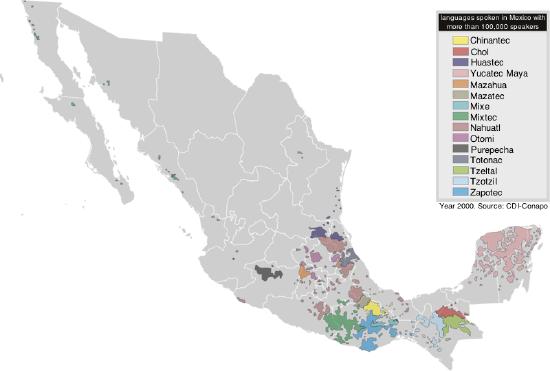

Avocado, tomato, and chocolate. You are likely familiar with at least some of these food items. Did you know that they all originally come from Mexico, and are all based on Nahuatl words (ahuacatl, tomatl, and chocolatl) that were eventually adopted by the English language?

Nahuatl is the language spoken by the Nahua ethnic group that is found today in Mexico, but with deep historical roots. You might know one Nahua group: the Aztecs, more accurately called the Mexica. The Mexica were one of many Mesoamerican cultural groups that flourished in Mexico prior to the arrival of Europeans in the sixteenth century.

Where was Mesoamerica?

Mesoamerica refers to the diverse civilizations that shared similar cultural characteristics in the geographic areas comprising the modern-day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Some of the shared cultural traits among Mesoamerican peoples included a complex pantheon of deities, architectural features, a ballgame, the 260-day calendar, trade, food (especially a reliance on maize, beans, and squash), dress, and accoutrements (such as earspools).

Some of the most well-known Mesoamerican cultures are the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, Mixtec, and Mexica (or Aztec). The geography of Mesoamerica is incredibly diverse—it includes humid tropical areas, dry deserts, high mountainous terrain, and low coastal plains. An anthropologist named Paul Kirchkoff first used the term “Mesoamerica” (meso is Greek for “middle” or “intermediate”) in 1943 to designate these geographical areas as having shared cultural traits prior to the invasion of Europeans, and the term has remained.

Typically when we discuss Mesoamerican art we are referring to art made by peoples in Mexico and much of Central America. When people mention Native North American art, they are usually referring to indigenous peoples in the U.S. and Canada, even though these countries are technically all part of North America. More recently, archaeologists and art historians have considered connections between the Southwestern and Southeastern U.S. and Mesoamerica, an area sometimes called either the Greater Southwest or Greater Mesoamerica. Focusing on these connections demonstrates how people were in contact with one another through trade, shared beliefs, migration, or conflict. Ball courts, for instance, are found in Arizona sites such as the Pueblo Grande of the Hohokam. It is important to remember that modern-day geographic terms—like Mesoamerica or the Southwestern U.S.—are recent designations.

This essay generalizes about Mesoamerican cultures, but keep in mind that each possessed unique qualities and cultural differences. Mesoamerica was not homogenous.

When was Mesoamerica?

Art historians and archaeologists divide Mesoamerican history into distinct periods and some of these periods are then further divided into the sub-periods—early, middle, and late.

| Period | Dates | Cultures |

| Archaic Period | c. 3500-1500 BCE | |

| Pre-Classical (or Formative) Period | c. 1800 BCE-250 CE | Olmec, Teotihuacan, Tlatilco, Maya, Zapotec |

| Classic Period | c. 150-650 CE | Teotihuacan, Maya |

| Epiclassic Period | c. 650-900 CE | Maya, Toltec |

| Postclassic Period | c. 900-1519 CE | Toltec, Aztec (Mexica), Mixtec, Maya |

The date for the end of the Postclassic period is somewhat contested as it presumes that Mesoamerican culture largely ended with the arrival of Spaniards into the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519, though Mesoamerican culture continued under Spanish control, albeit significantly transformed.You might also encounter the term Pre-Columbian, which is a term designating indigenous cultures prior to the arrival of Columbus. It includes those in Mesoamerica, as well as in South America and the Caribbean. This term is problematic for several reasons, as discussed at the beginning of this chapter.

What language did people speak?

There was no single language that united the peoples of Mesoamerica. Linguists believe that Mesoamericans spoke more than 125 different languages. For instance, Maya peoples did not speak “Mayan”, but could have spoken Yucatec Maya, K’iche, or Tzotzil among many others. The Mexica belonged to the bigger Nahua ethnic group, and therefore spoke Nahuatl.

To students learning about Mesoamerica for the first time, the incredible diversity of people, languages, and even deities can be overwhelming. I recall my first Mesoamerican art history class vividly. I was intimidated by my lack of familiarity with different Mesoamerican words, languages, and cultural groups. By the end of the semester I was proud that I could differentiate between the Zapotec and Mixtec, and could spell Tlaloc. It took me a few more years to be able to spell and pronounce words like Tlacaxipehualiztli (Tla-cawsh-ee-pay-wal-eeezt-li) or Huitzilopochtli (Wheat-zil-oh-poach-lee).

Writing

Mesoamerican writing systems vary by culture. Rebus writing (writing with images) was common among many groups, like the Nahua and Mixtec. Imagine drawing an eye, a heart, and an apple. You’ve just used rebus writing to communicate “I love apples” to anyone familiar with these symbols. Many visual writing systems in Mesoamerica functioned similarly—although the previous example was simplified for the sake of clarity. You might encounter the phrases “writing without words” or “writing with signs” used to describe many writing systems in Mesoamerica. It is also called pictographic, ideographic, or picture writing.

Only the Maya used a writing system like ours, where signs like letters designate sounds and syllables, and combined together to create words. Maya hieroglyphic writing is logographic, which means it uses a sign (think of a picture, symbol, or a letter) to communicate a syllable or a word.

The 260-day ritual calendar vs. the 365-day calendar

Other shared features among Mesoamerican peoples were the 260-day and 365-day calendars. The 260-day calendar was a ritual calendar, with 20 months of 13 days. Based on the sun, the 365-day calendar had 18 months of 20 days, with five “extra” nameless days at the end. It was the count of time used for agriculture.

Imagine both of these calendars as interlocking wheels. Every 52 years they completed a full cycle, and during this time special rituals commemorated the cycle. For example, the Mexica celebrated the New Fire Ceremony as a period of renewal. These cycles were understood as life cycles, and so reflect creation, death, and rebirth. The Maya (especially during the Classic period), also used a Long Count calendar in addition to the two already mentioned (rather than a cyclical calendar, the Long Count marked time as if along an extended line that does not repeat).

Religion and pantheon of gods

A complex pantheon of gods existed within each Mesoamerican culture. Many groups shared similar deities, although there was a great deal of variation. Deities that had important roles across Mesoamerica included a storm/rain god and a feathered serpent deity. Among the Mexica, this storm/rain god was known as Tlaloc, and the feathered serpent deity was known as Quetzalcoatl. The Maya referred to their storm/rain deity as Chaac (there are multiple spellings). The equivalent of Quetzalcoatl among different Maya groups included Kukulkan (Yucatec Maya) and Q’uq’umatz (K’iche Maya). Cocijo is the Zapotec equivalent of the storm/rain god. Many artworks exist that show these two deities with similar features. The storm/rain deity often has goggle eyes and an upturned mouth/snout. Feathered serpent deities typically showed serpent features paired with feathers.

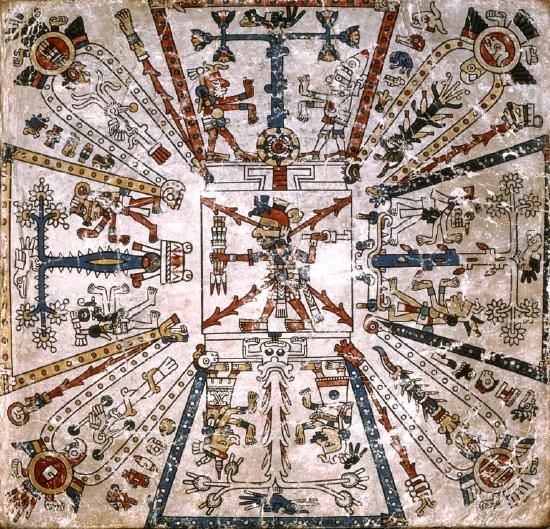

It is difficult to generalize about Mesoamerican religious beliefs and cosmological ideas because they were so complex. Throughout Mesoamerica, there was a general belief in the universe’s division along two axes: one vertical, the other horizontal. At the center, where these two axes meet, is the axis mundi, or the center (or navel) of the universe. On the horizontal plane, four directions branch off from the axis mundi. Think of the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west). On the vertical plane, we generally find the world split into three major realms: the celestial, terrestrial, and underworld.

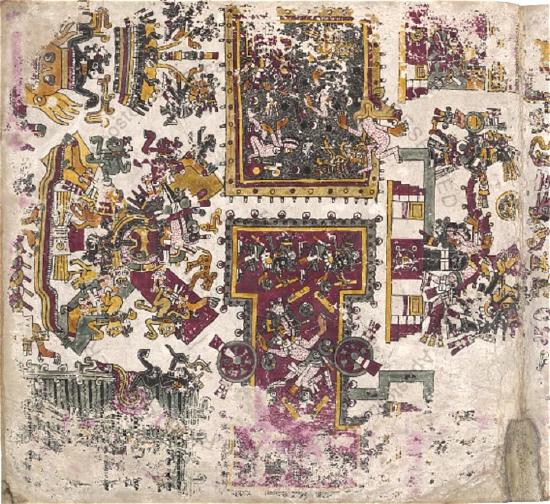

One Mexica example helps to clarify this complex cosmological system. An image in the Codex Féjervary-Mayer displays the cosmos’s horizontal axis. In the center is the deity Xiuhtecuhtli (a fire god), standing in the place of the axis mundi. Four nodes (what look almost like trapezoidal petals) branch off from his position, creating a shape called a Maltese Cross. East (top) is associated with red, south (right) with green, west (bottom) with blue, and north (left) with yellow. A specific plant and bird accompany each world direction: blue tree and quetzal (east), cacao and parrot (south), maize and blue-painted bird (west), and cactus and eagle (north). Two figures flank the plant in each arm of the cross. Together, these figures and Xiuhtecuhtli represent the Nine Lords of the Night. This cosmogram describes how the Mexica conceived of the universe.

The ballgame

Peoples across Mesoamerica, beginning with the Olmecs, played a ritual sport known as the ballgame. Ballcourts were often located in a city’s sacred precinct, emphasizing the importance of the game. Solid rubber balls were passed between players (no hands allowed!), with the goal of hitting them through markers. Players wore padded garments to protect their bodies from the hard ball.

The meanings of the ballgame were many and varied. It could symbolize a range of larger cosmological ideas, including the movement of the sun through the underworld every night. War captives also played the game against members of a winning city or group, with the game symbolizing their defeat in war. Sometimes a game was even played instead of going to war.

Numerous objects display aspects of the ballgame, attesting to its significant role across Mesoamerica. We have examples of clay sculptures of ballgames occurring on courts, such as in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\). Ballplayers are also frequent subjects in Maya painted ceramic vessels and sculptures. Stone reliefs at El Tajin and Chichen Itza depict different moments of a ballgame culminating in ritual sacrifice. Painted pictorial codices, such as the Codex Borgia (Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)), display I-shaped ballcourts, and stone depictions of ballgame clothing have been found. Today, people in Mexico still play a version of the ballgame.

Mesoamerican societies continue to impress us with their sophistication and accomplishments, notably their artistic achievements. Our understanding continues to expand with ongoing research and archaeological excavations. Recent excavations in Mexico City, for instance, uncovered a new monumental Mexica sculpture buried with some of the most unique objects we’ve ever seen in Mexica art. With these discoveries, our understanding of the Mexica will no doubt grow and change.

There are ballcourts closer to us here in California than El Tajin and Chichen Itza, as the tradition made its way, with variations, into North America. Here is a photograph of the reconstructed remains of a ballcourt at the Wupatki National Monument near Flagstaff, Arizona. More than 200 of these ballcourts, built between 750-1200 CE, have been discovered in Arizona, suggesting their importance for the Wupatki and their southern neighbors, who likely “borrowed and modified the ballcourt idea from earlier contact” with the native cultures of Mexico. [Wupatki National Monument signage]

To learn more about the Wupatki and this site, visit Wupatki at the National Park Service.

Cultures of Mesoamerica

adapted from Boundless Art History

Mesoamerica was dominated by three cultures in the Pre-Classical (up to 200 CE) to Postclassic periods (circa 1580 CE): the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec. Mesoamerica is a region in the Americas that extends from central Mexico to northern Costa Rica. Three cultures dominated the pre-Columbian history of Mesoamerica: the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations.

Olmec Culture

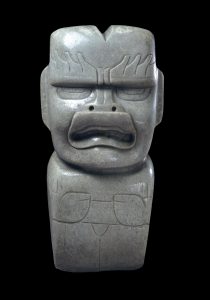

The Olmec civilization, which flourished from 1200–400 BCE, defines the Pre- Classical period; the Olmecs are generally considered the forerunner of all Mesoamerica cultures including the Maya and Aztecs. Primarily centered in the modern states of Tabasco and Veracruz in the Gulf of Mexico, the Olmec people are known for creating an abundance of small and extraordinarily detailed jade figurines. The figurines typically exhibit complex shapes such as human figures, human-animal composites of deities and gods, and animals like cats and birds. Although we don’t know the specific purpose of these jade objects, their presence in some Olmec graves suggests they served a religious purpose in addition to being signs of wealth and goods for trade.

This ceremonial axe, carved from a sizeable chunk of semiprecious green stone, takes the form of a mythical hybrid figure. The British Museum gives the following Curator's comments:

This massive ceremonial axe (celt) combines characteristics of the caiman and the jaguar, the most powerful predators inhabiting the rivers and forests of the tropical lowlands. The pronounced cleft in the head mimics the indentation found on the skulls of jaguars and has been compared to the human fontanelle. These clefts feature on other Olmec sculptures and in imagery in which vegetal motifs spring from similar cracks and orifices, alluding to the underground sources of fertility and life. The crossed bands glyph lightly incised on the waistband represents an entrance or opening. The combination of symbols on the axe proclaims its magical power to cleave open the portals to the underworld, reinforcing the association of "celts" with agriculture and maize - ground stone axes were indispensable for felling forest trees and clearing ground for planting. Utilitarian objects were often personified in this way so as to represent the qualities and attributes of supernatural deities. Accumulating inner soul force, they became potent objects that were handed down from one generation to the next.

Although this comment references utilitarian objects, this object's size and material suggest that this was a ceremonial, rather than functional, axe. If you'd like to learn more about these hybrid figures in Mesoamerican art, and especially the role and significance of crocodilians in addition to jaguars, check out the open-access journal article by Richard Takkou-Neofytou, "Were-Jaguars and Crocodilians: A Need to Redefine."

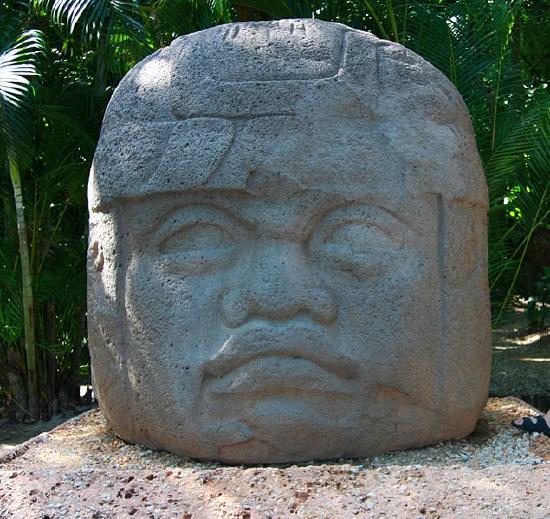

The Olmec are also known for building massive stone sculptures, many of which were discovered at La Venta in the modern Mexican state of Tabasco. Made from basalt rock from the Tuxtla mountains to the north, the Olmec used this rock to create altars, stelae, and colossal heads. Each head is rendered as a distinct individual and is thought to resemble an Olmec ruler. Each ruler’s personality is represented in the distinct headdresses that adorn the sculptures’ heads.

These massive basalt boulders were transported from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas Mountains of Veracruz. When originally displayed in Olmec centers, the heads were arranged in lines or groups; however, the method used to transport the stone to these sites remains unclear. Given the enormous weight of the stones and the manpower required to transport them over large distances, it is probable that the colossal portraits represent powerful Olmec rulers. The colossal heads range in height from 5 to 12 feet and portray adult males wearing close-fitting caps with chin straps and large, round earspools. The fleshy faces have almond-shaped eyes, flat, broad noses, thick, protruding lips, and downturned mouths. Each face has a distinct personality, suggesting that they represent specific individuals.

The discovery of a colossal head at Tres Zapotes in the nineteenth century spurred the first archaeological investigations of Olmec culture by Matthew Stirling in 1938. Seventeen confirmed examples are traced to four sites within the Olmec heartland on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Most colossal heads were sculpted from spherical boulders, but two from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán were recarved from massive stone thrones. An additional monument at Takalik Abaj in Guatemala is a throne that may have been carved from a colossal head. This is the only known example from outside the Olmec heartland.

Dating the monuments remains difficult because of the movement of many from their original contexts prior to archaeological investigation. Most have been dated to the Early Preclassic (or Formative) period (1500–1000 BCE) with some to the Middle Preclassic (1000–400 BCE) period. The smallest weighs six tons, while the largest is estimated to weigh 40 to 50 tons, although it was abandoned and left unfinished close to the source of its stone.

Teotihuacan

At its height, Teotihuacan was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of 200,000. It was a primary center of commerce and manufacturing. Located some 30 miles northeast of present-day Mexico City, Teotihuacan experienced a period of rapid growth early in the first millennium CE. By 200 CE, it emerged as a significant center of commerce and manufacturing, the first large city-state in the Americas. At its height between 350 and 650 CE, Teotihuacan covered nearly nine miles and had a population of about 200,000, making it one of the largest cities in the world. One reason for its dominance was its control of the market for high-quality obsidian. This volcanic stone, made into tools and vessels, was traded for luxury items such as the green feathers of the quetzal bird, used for priestly headdresses, and the spotted fur of the jaguar, used for ceremonial garments.

The people of Teotihuacan worshipped deities that were recognizably similar to those worshipped by later Mesoamerican people, including the Aztecs, who dominated central Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest. Among these are the Rain or Storm God (god of fertility, war, and sacrifice), known to the Aztecs as Tlaloc, and the Feathered Serpent, known to the Maya as Kukulcan and to the Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl.

Mesoamerican pyramids are not true pyramids with a pointed apex at top. Instead they have flat tops, often supporting a temple, and stairs on the face of the structure.

Teotihuacan’s principal monuments include the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and the Ciudadela (Spanish for fortified city center), a vast sunken plaza surrounded by temple platforms. The city’s principal religious and political center, the Ciudadela could accommodate an assembly of more than 60,000 people. Its focal point was the pyramidal Temple of the Feathered Serpent. This seven-tiered structure exhibits the talud-tablero construction that is a hallmark of the Teotihuacan architectural style. The sloping base, or talud, of each platform supports a vertical tablero, or entablature, which is surrounded by frame and filled with sculptural decoration. The Temple of the Feathered Serpent was enlarged several times, and as was characteristic of Mesoamerican pyramids, each enlargement completely enclosed the previous structure like the layers of an onion. Archaeological excavation of this temple’s earlier-phase tableros and a stairway balustrade have revealed painted heads of the Feathered Serpent, the goggle-eyed Rain or Storm God, and reliefs of aquatic shells and snails. The flat, angular, abstract style, typical of Teotihuacan art, is in marked contrast to the curvilinear style of Olmec art.

The Decline

Sometime in the middle of the seventh century disaster struck Teotihuacan. The ceremonial center burned and the city went into a permanent decline. Nevertheless, its influence continued as other centers throughout Mesoamerica and as far south as the highlands of Guatemala borrowed and transformed its imagery over the next several centuries. The site was never entirely abandoned as it remained a legendary pilgrimage center. The much later Aztec people (c. 1300-1525 CE) revered the site as the place where they believed the gods created the sun and the moon. In fact, the name “Teotihuacan” is actually an Aztec word meaning “Gathering Place of the Gods.”

Mayan Art

Mayan art includes a wide variety of objects, commissioned by rulers, that depict scenes of both elite and everyday society.

Mayan Portraiture

Strong cultural influences stemming from the Olmec tradition and Teotihuacan contributed to the development of the Mayan city center and the culture’s Classic artistic tradition. The most sacred and majestic buildings of Mayan cities were built in enclosed, centrally located precincts. The Maya held dramatic rituals within these highly sculptured and painted environments. For example, the grand pyramids of Copan and Tikal are among the most imposing buildings the Maya erected; each contains sculpted portraits that glorified the city’s rulers.

Stele H in the Great Plaza at Copan represents one of the city’s foremost leaders, 18-Rabbit, who reigned from 695-738 CE. During the ruler’s long reign, Copan reached its greatest physical extent and breadth of political influence. On Stele H, 18-Rabbit wears an elaborate headdress and ornamented kilt and sandals. He holds across his chest a double-headed serpent bar, symbol of the sky and of his absolute power. His features, although idealized, have the quality of a portrait likeness. The Mayan elite, like the Egyptian pharaohs, tended to have themselves portrayed as eternally youthful. The dense, deeply carved ornamental details that frame the face and figure stand almost clear of the main stone block and wrap around the sides of the stele. The stele was originally painted, with remnants of red paint visible on many stelae and buildings in Copan.

Clay Sculpture

Many small clay figures from the Classic Mayan period remain in existence. These free-standing objects illustrate aspects of everyday Mayan life. As a group, they are remarkably life-like, carefully descriptive, and even comic at times. They represent a wider range of human types and activities than commonly depicted on Mayan stelae. Ball players, women weaving, older men, dwarves, supernatural beings, and amorous couples, as well as elaborately attired rulers and warriors, comprise one of the largest groups of surviving Mayan art. Many of the hollow figurines are also whistles. They were made in ceramic workshops and painted with Maya Blue, a dye unique to Mayan and Aztec artists. Small clay figures found in burial sites were made to accompany the Mayan dead on their inevitable voyage to the Underworld.

Painted Vases

The Maya painted vivid narrative scenes on the surfaces of cylindrical vases. A typical vase design depicts a palace scene where an enthroned Mayan ruler sits surrounded by courtiers and attendants. The figures wear simple loincloths, turbans of wrapped cloth and feathers, and black body paint. These painted vases may have been used as drinking and food vessels for noble Maya, but their final destination was the tomb, where they accompanied the deceased to the Underworld. They likely were commissioned by the deceased before his death or by his survivors, and were occasionally sent from distant sites as funerary offerings.

Mayan Architecture: Palenque

The Maya had complex architectural programs. They built imposing pyramids, temples, palaces, and administrative structures in densely populated cities.

In Palenque, Mexico, a prominent city of the Classic period, the major buildings are grouped on high ground. The central group of structures includes the Palace (possibly an administrative and ceremonial center as well as a residential structure), the Temple of the Inscriptions, and two other temples. Most of the structures in the complex were commissioned by a powerful ruler, Lord Pakal, who reigned from 615 to 638 CE, and his two sons, who succeeded him.

Temple of the Inscriptions

The Temple of the Inscriptions is a nine-level pyramid that rises to a height of about 75 feet. The consecutive layers probably reflect the belief, current among the Aztec and Maya at the time of the Spanish conquest, that the underworld had nine levels. Priests would climb the steep stone staircase on the exterior to reach the temple on top, which recalls the kind of pole-and-thatch houses the Maya still build in parts of the Yucatan today. The roof of the temple was topped with a crest known as a roof comb, and its façade still retains much of its stucco sculpture. Inscriptions line the back wall of the outer chamber, giving the temple its name.

The Palace

Across from the Temple of Inscriptions is the Palace, a complex of several adjacent buildings and courtyards built on a wide artificial terrace. The Palace was used by the Mayan aristocracy for bureaucratic functions, entertainment, and ritual ceremonies.

Numerous sculptures and bas-relief carvings within the Palace have been conserved. The Palace’s most unusual and recognizable feature is the four-story tower known as the Observation Tower. Like many other buildings at the site, the Observation Tower exhibits a mansard roof. The Palace was equipped with numerous large baths and saunas which were supplied with fresh water by an intricate water system. An aqueduct constructed of great stone blocks with a six-foot-high vault diverts the Otulum River to flow underneath the main plaza.

Mayan Architecture: Chichen Itza

As the focus of Maya civilization shifted northward in the Post-Classic period, a northern Maya group called the Itza rose to prominence. Their principal center, Chichen Itza, (Yucatan State) Mexico, which means “at the mouth of the well of the Itza,” flourished from the 9th to 13th centuries CE, eventually covering about six square miles.

El Castillo

One of Chichen Itza’s most conspicuous structures is El Castillo (Spanish for the castle), a massive nine-level pyramid in the center of a large plaza with a stairway on each side leading to a square temple on the pyramid’s summit. At the spring and fall equinoxes, the setting sun casts an undulating, serpent-like shadow on the stairways, forming bodies for the serpent heads carved at the base of the balustrades.

The Great Ball Court

The Great Ball Court northwest of the Castillo is the largest and best preserved court for playing the Mesoamerican ball game, an important sport with ritual associations played by Mesoamericans since 1400 BCE. The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 312 feet long. The walls of these platforms stand 26 feet high. Rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents are set high at the top of each wall at the center. At the base of the interior walls are slanted benches with sculpted panels of teams of ball players. In one panel, one of the players has been decapitated; the wound spews streams of blood in the form of wriggling snakes.

At one end of the Great Ball Court is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man (Templo del Hombre Barbado). This small masonry building has detailed bas-relief carving on the inner walls, including a center figure with decorative carvings that resemble facial hair. Built into the east wall are the Temples of the Jaguar. The Upper Temple of the Jaguar overlooks the ball court and has an entrance guarded by two large columns carved in the familiar feathered serpent motif. At the entrance to the Lower Temple of the Jaguar is another Jaguar throne similar to the one in the inner temple of El Castillo.

Ceramics of the Veracruz

Ceramic figurines are a hallmark of Classic Veracruz art, and the Veracruz people produced a variety of small clay figures in multiple locations. The modern state of Veracruz lies along the Mexican Gulf Coast, north of the Maya lowlands and east of the highlands of central Mexico. Culturally diverse and environmentally rich, the people of Veracruz took part in dynamic interchanges between three regions that over the centuries included trade, warfare, and migration. During the middle centuries of the first millennium, the artistically gifted Veracruzanos created inventive ceramic sculpture in diverse yet related styles.

Until the early 1950s, Classic Veracruz ceramics were few, little understood, and generally without provenance (known history). Since then, the recovery of thousands of figurines and pottery pieces from sites such as Remojadas and Nopiloa (some initially found by looters), has expanded our understanding and filled many museum shelves. Artist and art historian Miguel Covarrubias described Classic Veracruz ceramics as “powerful and expressive, endowed with a charm and sensibility unprecedented in other, more formal cultures.”

Figurines from Remojadas and Nopiloa

Remojadas-style figurines, perhaps the most easily recognizable from this culture, are usually hand-modeled and often adorned with appliqués. Of particular note are the Sonrientes (Smiling) Figurines, with triangular-shaped heads and outstretched arms. Figurines from Nopiloa are often molded and usually less ornate, without appliqués. The Figure from Nopiloa provides scholars with an example of the clothing worn in ancient times, such as the loincloth and headdress. The flattened forehead on this smiling figure may represent the practice of intentional cranial deformation or may simply reflect an artistic convention. Many American cultures considered a flattened forehead desirable and used a variety of techniques to flatten the skulls of infants while they were still pliable.

Another smiling figure from the Remojadas region is a hollow ceramic sculpture representing an individual celebrating with music and dance. This bare-chested figure with open mouth and filed teeth stands energetically with legs spread and arms lifted as if caught in mid-motion. He wears a woven cap with geometric patterns, an elaborate skirt, circular earrings, a beaded necklace, and a bracelet. His face and body contain patterns evocative of body paint, including slight lines emanating from his lower eyelids and onto his cheeks. This sculpture evokes a festive dance or ritual accompanied by the rhythmic reverberation of the hand-held rattle and celebratory sound escaping from the figure’s open mouth.

In contrast to Smiling Figures from Remojadas, the mold-made ceramic figure from Nopiloa depicts a bearded, mustachioed male wearing a ballgame yoke around his waist to protect him from the hard, solid rubber ball used in play. There are cylindrical ear ornaments in his ears and beneath his arm, a baton-like object perhaps related to the local incarnation of the game. The rules and manner in which the Mesoamerican ballgame was played varied among contemporary sites and evolved through time. Surviving evidence suggests human sacrifice was a frequent outcome, but the game may also have been played for other purposes such as sport. The people of ancient Veracruz interacted with people from other Mesoamerican cultures, and this Nopiloa figure displays motifs commonly found in Mayan art. Knotted ties like those around this player’s wrist and neck connote captured prisoners in Mayan pictorial language. A motif similar to the Maya mat, a symbol of rulership, appears on the flanged headdress of the ballplayer. Like Mayan figurines of this type, the body of this figure is a whistle, a musical instrument used in ritual and ceremony.

Mixtec Art

The Mixtecs were one of the most influential ethnic groups to emerge in Mesoamerica during the Post-Classic period. Never a united nation, the Mixtecs waged war and forged alliances among themselves as well as with other peoples in their vicinity. They also produced beautiful manuscripts and metal work and influenced the international artistic style used from Central Mexico to Yucatan.

During the Classic period, the Mixtecs lived in hilltop settlements of northwestern Oaxaca, a fact reflected in their name in their own language, Ñuudzahui, meaning “People of the Rain.” During the Post-Classic period, the Mixtecs slowly moved into adjacent valleys and then into the great Valley of Oaxaca. This time of expansion is recorded in a large number of deerskin manuscripts called codices, only eight of which have survived. Nevertheless, these manuscripts allow us to trace Mixtec history from 1550 CE back to 940 CE, deeper in time than any other Mesoamerican culture except the Maya.

Mixtec Codices

Mixtec codices represent a type of writing classified as logographic, meaning the characters and pictures used represent complete words and ideas instead of syllables or sounds. In Mixtec, the relationships among pictorial elements denote the meaning of the text, whereas in other Mesoamerican writing the pictorial representations are not incorporated into the text. Common topics found in the codices are biographies of rulers and other influential figures, records of elite family trees, mythologies, and accounts of ceremonies.

The detail from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall depicts a group of warriors conquering a town (an event noted by the warriors’ drawn weapons and the arrow piercing the hill). Above each participant’s head is a glyph, or pictograph, with a dot. The glyphs below the warriors are calendrical day signs. They are also, however, the names of Mixtec nobles; among this group, a person’s name was often his or her birthday.

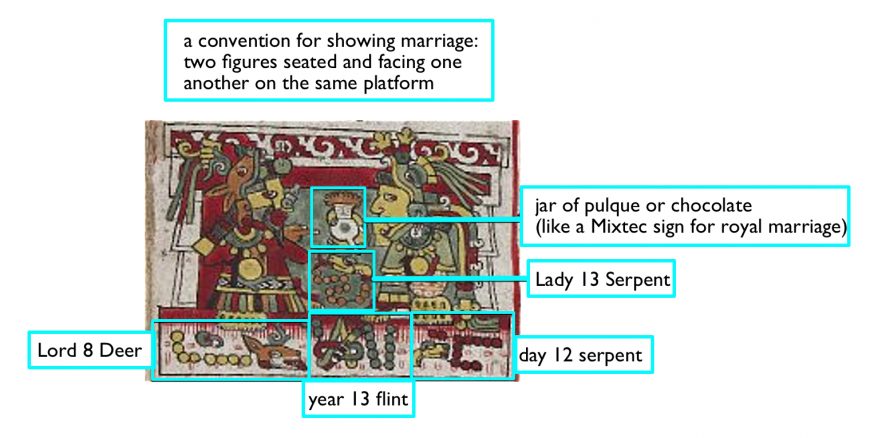

Pre-Columbian Mixtec are mainly concerned with histories. They record events such as royal births, wars and battles, royal marriages, forging of alliances, pilgrimages, and death of rulers. In addition to the calendrical signs used for dating events and naming individuals, the Mixtecs used a combination of conventionalized pictures and glyphs to illustrate the type and nature of the event. One example is the wedding scene, usually shown as two individuals of opposite sex facing each other and sitting on jaguar-pelt chairs, as illustrated by a scene from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall which records the marriage of the legendary Mixtec King 8 Deer “Tiger Claw” of Tilantongo to Lady 13 Serpent in 1051 CE.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Maya Jiménez, "Defining ‘Pre-Columbian’ and ‘Mesoamerica,’" in Smarthistory, August 19, 2016. (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, "Mesoamerica, an introduction," in Smarthistory, September 12, 2017. (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Lumen Learning, “Mesoamerica.” (CC BY-SA)