4.1: North America (Mississippi/Ancient Fort, Ancestral Puebloan)

- Page ID

- 108713

North America: about geography and chronological periods in Native American art

Typically when people discuss Native American art they are referring to peoples in what is today the United States and Canada. You might sometimes see this referred to as Native North American art, even though Mexico, the Caribbean, and those countries in Central America are typically not included. These areas are commonly included in the arts of Mesoamerica (or Middle America), even though these countries are technically part of North America.

So how do we consider so many groups and of such diverse natures? We tend to treat them geographically: Eastern Woodlands (sometime divided between North and Southeast), Southwest and West (or California), Plains and Great Basin, and Northwest Coast and North (Sub-Arctic and Arctic). While this is by no means a perfect way of addressing the varied tribes and First Nations within these areas, such a map can help to reveal patterns and similarities.

Chronology

Chronology (the arrangement of events into specific time periods in order of occurrence) is tricky when discussing Native American or First Nations art. Each geographic region is assigned different names to mark time, which can be confusing to anyone learning about the images, objects, and architecture of these areas for the first time. For instance, for the ancient Eastern Woodlands, you might read about the Late Archaic (c. 3000–1000 BCE), Woodland (c. 1100 BCE–1000 CE), Mississippian (c. 900–c. 1500/1600 CE), and Fort Ancient (c. 1000–1700) periods. But if we turn to the Southwest, there are alternative terms like Basketmaker (c. 100 BCE–700 CE) and Pueblo (700–1400 CE). You might also see terms like pre- and post-Contact (before and after contact with Europeans and Euro-Americans) and Reservation Era (late nineteenth century) that are used to separate different moments in time. Some of these terms speak to the colonial legacy of Native peoples because they separate time based on interactions with foreigners. Other terms like Prehistory have fallen out of favor and are problematic since they suggest that Native peoples didn’t have a history prior to European contact.

Organization

We arrange Native American and First Nations material prior to c. 1500 in a separate section which includes material about the Ancestral Puebloans, Moundbuilders, and Mississippian peoples. Those objects and buildings created after c. 1500 are in their own section, which will hopefully highlight the continuing diversity of Native groups as well as the transformations (sometimes violent ones) occurring throughout parts of North America. Artists working after 1914 (or the beginning of WWI) are located in both the Art of the Americas section, and in the modern and contemporary areas.

Terms and Issues in Native American Art

by Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, the Dakotas, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, Wisconsin, Wyoming—all state names derived from Native American sources. Pontiac, moose, raccoon, pecan, kayak, squash, chipmunk, Winnebago. These common words also derive from different Native words and demonstrate the influence these groups have had on the United States. Pontiac, for instance, was an 18th century Ottawa chief (also called Obwandiyag), who fought against the British in the Great Lakes region. The word “moose,” first used in English in the early seventeenth century during colonization, comes from Algonquian languages.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes persist when discussing Native American arts and cultures, and sadly many people remain unaware of the complicated and fascinating histories of Native peoples and their art. Too many people still imagine a warrior or chief on horseback wearing a feathered headdress, or a beautiful young “princess” in an animal hide dress (what we now call the Indian Princess, as is imagined in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Popular culture and movies perpetuate these images, and homogenize the incredible diversity of Native groups across North America. There are too many different languages, cultural traditions, cosmologies, and ritual practices to adequately make broad statements about the cultures and arts of the indigenous peoples of what is now the United States and Canada.

In the past, the term “primitive” has been used to describe the art of Native tribes and First Nations. This term is deeply problematic—and reveals the distorted lens of colonialism through which these groups have been seen and misunderstood. After contact, Europeans and Euro-Americans often conceived of the Amerindian peoples of North America as noble savages (a primitive, uncivilized, and romanticized “Other”). This legacy has affected the reception and appreciation of Native arts, which is why much of it was initially collected by anthropological (rather than art) museums. Many people viewed Native objects as curiosities or as specimens of “dying” cultures—which in part explains why many objects were stolen or otherwise acquired without approval of Native peoples. Many sacred objects, for example, were removed and put on display for non-Native audiences. While much has changed, this legacy lives on, and it is important to be aware of and overcome the many stereotypes and biases that persist from prior centuries.

Repatriation

One significant step that has been taken to correct some of this colonial legacy has been NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. This is a U.S. federal law that dictates that “human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, referred to collectively in the statute as cultural items” be returned to tribes if they can demonstrate “lineal descent or cultural affiliation.” Many museums in the U.S. have been actively trying to repatriate items and human remains. For example, in 2011, a museum returned a wooden box drum, a hide robe, wooden masks, a headdress, a rattle, and a pipe to the Tlingít T’akdeintaan Clan of Hoonah, Alaska. These objects were purchased in 1924 for $500.

In the 19th century, many groups were violently forced from their ancestral homelands onto reservations. This is an important factor to remember when reading the essays and watching the videos in this section because the art changes—sometimes very dramatically—in response to these upheavals. You might read elsewhere that objects created after these transformations are somehow less authentic because of the influence of European or Euro-American materials and subjects on Native art. However, it is crucial that we do not view those artworks as somehow less culturally valuable simply because Native men and women responded to new and sometimes radically changed circumstances.

Many twentieth and twenty-first century artists, including Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Sioux), Alex Janvier (Chipewyan [Dene]) and Robert Davidson (Haida), don’t consider themselves to work outside of so-called “traditional arts.” In 1958, Howe even wrote a famous letter commenting on his methods when his work was denounced by Philbrook Indian Art Annual Jurors as not being “authentic” Native art:

Who ever said that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style has poor knowledge of Indian art indeed. There is much more to Indian Art than pretty, stylized pictures. There was also power and strength and individualism (emotional and intellectual insight) in the old Indian paintings. Every bit in my paintings is a true, studied fact of Indian paintings. Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting, with no right for individualism, dictated to as the Indian has always been, put on reservations and treated like a child, and only the White Man knows what is best for him? Now, even in Art, ‘You little child do what we think is best for you, nothing different.” Well, I am not going to stand for it. Indian Art can compete with any Art in the world, but not as a suppressed Art…. [Oscar Howe and the Philbrook Museum of Art, 1958]

More terms and issues

The word Indian is considered offensive to many peoples. The term derives from the Indies, and was coined after Christopher Columbus bumped into the Caribbean islands in 1492, believing, mistakenly, that he had found India. Other terms are equally problematic or generic. You might encounter many different terms to describe the peoples in North America, such as Native American, American Indian, Amerindian, Aboriginal, Native, Indigenous, First Nations, and First Peoples.

Native American is used here because people are most familiar with this term, yet we must be aware of the problems it raises. The term applies to peoples throughout the Americas, and the Native peoples of North America, from Panama to Alaska and northern Canada, are incredibly diverse. It is therefore important to represent individual cultures as much as we possibly can. The essays here use specific tribal and First Nations names so as not to homogenize or lump peoples together. On Smarthistory, the artworks listed under Native American Art are only those from the United States and Canada, while those in Mexico and Central America are located in other sections.

You might also encounter words like tribes, clans, or bands in relation to the social groups of different Native communities. The United States government refers to an Indigenous group as a “tribe,” while the Canadian government uses the term “band.” Many communities in Canada prefer the term “nation.”

Identity

In order to be legally classified as an indigenous person in the United States and Canada, an individual must be officially listed as belonging to a specific tribe or band. This issue of identity is obviously a sensitive one, and serves as a reminder of the continuing impact of colonial policy. Many contemporary artists, including James Luna (Pooyukitchum/Luiseño) and Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Nation), address the problem of who gets to decide who or what an Indian is in their work.

Luna’s Artifact Piece (1987) and Take a Picture with a Real Indian (1993) both confront issues of identity and stereotypes of Native peoples. In Artifact Piece, Luna placed himself into a glass vitrine (like the ones we often see in museums) as if he were a static artifact, a relic of the past, accompanied by personal items like pictures of his family. In Take a Picture with a Real Indian, Luna asks his audience to come take a picture with him. He changes clothes three times. He wears a loincloth, then a loincloth with a feather and a bone breastplate, and then what we might call “street clothes.” Most people choose to take a picture with him in the former two, and so Luna draws attention to the problematic idea that somehow he is less authentically Native when dressed in jeans and a t-shirt.

Even the naming conventions applied to peoples need to be revisited. In the past, the Navajo term “Anasazi” was used to name the ancestors of modern-day Puebloans. Today, “Ancestral Puebloans” is considered more acceptable. Likewise, “Eskimo” designated peoples in the Arctic region, but this word has fallen out of favor because it homogenizes the First Nations in this area. In general, it is always preferable to use a tribe or Nation’s specific name when possible, and to do so in its own language.

Fusing Historical Knowledge with Scientific Advances

Historically, archaeologists and art historians have been associated with and complicit in grave robbing, particularly Indigenous graves. Museums have been equally problematic in collecting and showcasing human remains, often refusing to repatriate them. A recent New York Times video about the process of searching for the graves of Canada’s Indigenous children highlights pressing and ongoing issues facing many Indigenous communities. The grim and moving story documents how archaeologists are combining oral interviews with new technology to locate children’s graves at Canada’s residential boarding schools. Through interviews with elders from the Muskowekwan First Nation community who are survivors of the boarding schools, archaeologists are mapping out the school properties and using advanced ground-penetrating radar technology to scan the ground and find unmarked graves in the places specified by the elders. This validates reports that have long been acknowledged within the community, while bringing the abuses to the surface internationally and offering communities a chance to heal, grieve, and give their ancestors proper burials.

Such a fusing of oral tradition and advanced scientific technology is important to the fields of both archaeology and art history for a number of reasons. First, it underscores that this is not ancient history: ongoing contemporary issues persist around the treatment and restitution of human remains and ancestral items. Second, it reminds viewers that graves and artifacts are about real people and family members—ancestors—and not just objects. And finally, it prompts art historians to listen to and trust Native communities, particularly in the face of such violent pasts. In mixing historical knowledge held by elders with high tech advancements and archaeological tools, such research teams are forging new roads for the disciplines of art history and archaeology. Instead of digging into the earth because something might be buried there, teams are returning the decision-making power and sovereignty to local communities, allowing them to determine what is best. This approach is dramatically different from the archaeological practices described in later chapters, in which foreign teams of Europeans descended upon ancient tombs and graves with little consideration for the humans interred there.

The History and Future of NAGPRA

In 1990, the United States took a significant step in addressing human rights abuses and past archaeological violence through the collection of human remains. With the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, also known as NAGPRA, federal law now dictates that “certain Native American cultural items—human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony” be returned “to lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.”

Since its passage, NAGPRA has been considered largely successful in helping to return certain treasured and sacred objects. However, there have been hiccups, both on the mainland and in Hawaiʻi, where “tribal affiliation” is not defined in the same way. As Zachary Small reports, “[t]he remains of more than 116,000 Native American ancestors are still held by institutions around the country, and the National Park Service says that, for nearly all of them, the institutions have not linked the remains to a particular tribe, a designation known as ‘culturally affiliated’ that allows Indigenous groups to reclaim the bones of their forebears.”

The Biden-Harris Administration is planning to make regulatory adjustments that should speed up the repatriation process in addition to requiring museums and institutions to complete the affiliation process in identifying remains and artifacts. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo and first Native American to hold a cabinet post, is leading this move and drafting the regulatory changes, in consultation with tribal and Native Hawaiian communities.

Calls for an International NAGPRA

NAGPRA is a small step in the right direction in terms of repatriating sacred objects and human remains, but it only applies to the United States. Many ancestral human remains and sacred objects still lie in museum collections internationally. The 2015 documentary Te Kuhane O Te Tupuna (The Spirit of the Ancestors) documents the emotional story of one Rapanui family’s search for such repatriation. (Rapa Nui is a Polynesian island located in the South Pacific Ocean and is often called “Easter Island” by outsiders.) In the film, three generations travel to London and Paris in search of sacred ancestral remains and the lost moai Hoa Haka Nanaʻia who controversially resides in the British Museum. On this journey, they visit the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and as they survey objects from the Rapanui collection, Benedicto Tuki and his young granddaughter Mikaela Pakarati ask the curator what one unknown object is, wrapped in paper and lying amongst carved wooden figures. The curator opens it to reveal that it is a packet of human hair. Mikaela confirms that she is understanding correctly and stands in heartbreaking silence and horror with her grandpa, looking at the hair of an ancestor, now bundled in the basement of a museum 8,500 miles from home.

It is moments like these that help to both illuminate and humanize the very real need for an international NAGPRA, particularly from former colonial superpowers who often still hold an abundance of looted artifacts and human remains that remain sacred to the original owners and ancestors.

Fort Ancient Culture: Great Serpent Mound

by Dr. Katherine T. Brown

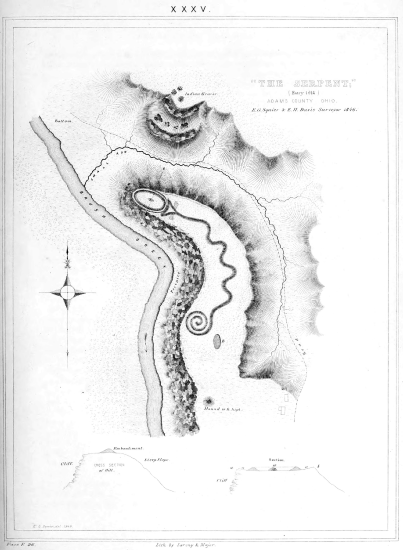

A serpent 1300 feet long

The Great Serpent Mound in rural, southwestern Ohio is the largest serpent effigy in the world. Numerous mounds were made by the ancient Native American cultures that flourished along the fertile valleys of the Mississippi, Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers a thousand years ago, though many were destroyed as farms spread across this region during the modern era. They invite us to contemplate the rich spiritual beliefs of the ancient Native American cultures that created them.

The Great Serpent Mound measures approximately 1,300 feet in length and ranges from one to three feet in height. The complex mound is both architectural and sculptural and was erected by settled peoples who cultivated maize, beans and squash and who maintained a stratified society with an organized labor force, but left no written records. Let’s take a look at both aerial and close-up views that can help us understand the mound in relationship to its site and the possible intentions of its makers.

Supernatural powers?

The serpent is slightly crescent-shaped and oriented such that the head is at the east and the tail at the west, with seven winding coils in between, as can be seen in the drawing in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). The shape of the head perhaps invites the most speculation. Whereas some scholars read the oval shape as an enlarged eye, others see a hollow egg or even a frog about to be swallowed by wide, open jaws. But perhaps that lower jaw is an indication of appendages, such as small arms that might imply the creature is a lizard rather than a snake. Many native cultures in both North and Central America attributed supernatural powers to snakes or reptiles and included them in their spiritual practices. The native peoples of the Middle Ohio Valley in particular frequently created snake-shapes out of copper sheets.

The mound conforms to the natural topography of the site, which is a high plateau overlooking Ohio Brush Creek. In fact, the head of the creature approaches a steep, natural cliff above the creek. The unique geologic formations suggest that a meteor struck the site approximately 250-300 million years ago, causing folded bedrock underneath the mound.

Celestial hypotheses

Aspects of both the zoomorphic form and the unusual site have associations with astronomy worthy of our consideration. The head of the serpent aligns with the summer solstice sunset, and the tail points to the winter solstice sunrise. Could this mound have been used to mark time or seasons, perhaps indicating when to plant or harvest? Likewise, it has been suggested that the curves in the body of the snake parallel lunar phases, or alternatively align with the two solstices and two equinoxes.

Some have interpreted the egg or eye shape at the head to be a representation of the sun. Perhaps even the swallowing of the sun shape could document a solar eclipse. Another theory is that the shape of the serpent imitates the constellation Draco, with the Pole Star matching the placement of the first curve in the snake’s torso from the head. An alignment with the Pole Star may indicate that the mound was used to determine true north and thus served as a kind of compass.

Of note also is the fact that Halley’s Comet appeared in 1066, although the tail of the comet is characteristically straight rather than curved. Perhaps the mound served in part to mark this astronomical event or a similar phenomenon, such as light from a supernova. In a more comprehensive view, the serpent mount may represent a conglomerate of all celestial knowledge known by these native peoples in a single image.

Who built it?

Determining exactly which culture designed and built the effigy mound, and when, is a matter of ongoing inquiry. A broad answer may lie in viewing the work as being designed, built, and/or refurbished over an extended period of time by several indigenous groups. The leading theory is that the Fort Ancient Culture (1000-1650 CE) is principally responsible for the mound, having erected it in c. 1070 CE. This mound-building society lived in the Ohio Valley and was influenced by the contemporary Mississippian culture (700-1550), whose urban center was located at Cahokia in Illinois. The rattlesnake was a common theme among the Mississippian culture, and thus it is possible that the Fort Ancient Culture appropriated this symbol from them (although there is no clear reference to a rattle to identify the species as such).

An alternative theory is that the Fort Ancient Culture refurbished the site c. 1070, reworking a preexisting mound built by the Adena Culture (c. 1100 BCE-200 CE) and/or the Hopewell Culture (c. 100 BCE-550 CE.). Whether the site was built by the Fort Ancient peoples, or by the earlier Adena or Hopewell Cultures, the mound is atypical. The mound contains no artifacts, and both the Fort Ancient and Adena groups typically buried objects inside their mounds. Although there are no graves found inside the Great Serpent Mound, there are burials found nearby, but none of them are the kinds of burials typical for the Fort Ancient culture and are more closely associated with Adena burial practices. Archaeological evidence does not support a burial purpose for the Great Serpent Mound.

Debate continues

Whether this impressive monument was used as a way to mark time, document a celestial event, act as a compass, serve as a guide to astrological patterns, or provide a place of worship to a supernatural snake god or goddess, we may never know with certainty. One scholar has recently suggested that the mound was a platform or base for totems or other architectural structures that are no longer extant, perhaps removed by subsequent cultures. All to say, scholarly debate continues, based on on-going archaeological evidence and geological research. But without a doubt, the mound is singular and significant in its ability to provide tangible insights into the cosmology and rituals of the ancient Americas.

This neck ornament, or gorget, was found in a mound burial in Tennessee, but was carved into a coastal shell. In this Seeing America video, Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. David Penney, Associate Director for Museum Scholarship, Exhibitions, and Public Engagement at the National Museum of the American Indian, discuss the Mississippian period, including its cities and burial traditions, as well as the imagery and iconography of this intricately-incised ornament.

Gorget, c. 1250-1350, probably Middle Mississippian Tradition, whelk shell, 10 x 2 cm (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 18/853).

Mesa Verde

by Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank

Wanted: stunning view

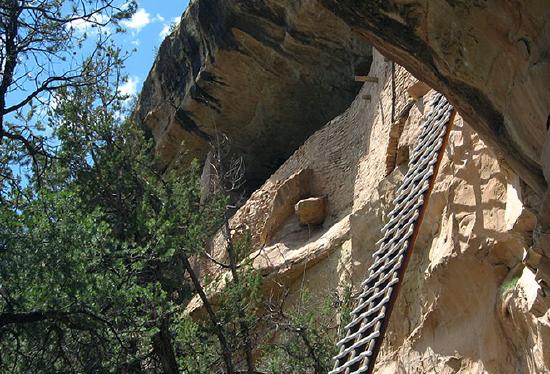

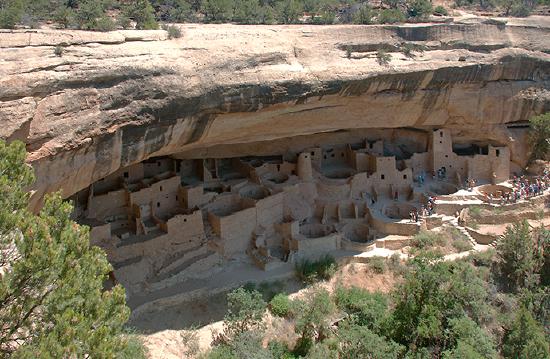

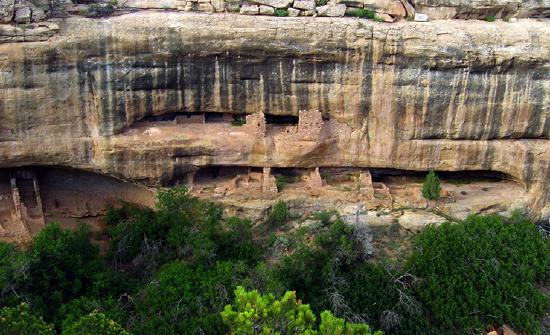

Imagine living in a home built into the side of a cliff. The Ancestral Puebloan peoples (formerly known as the Anasazi) did just that in some of the most remarkable structures still in existence today. Beginning after 1000-1100 CE, they built more than 600 structures (mostly residential but also for storage and ritual) into the cliff faces of the Four Corners region of the United States (the southwestern corner of Colorado, northwestern corner of New Mexico, northeastern corner of Arizona, and southeastern corner of Utah). The dwellings depicted here are located in what is today southwestern Colorado in the national park known as Mesa Verde (“verde” is Spanish for green and “mesa” literally means table in Spanish but here refers to the flat-topped mountains common in the southwest).

The most famous residential sites date to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Ancestral Puebloans accessed these dwellings with retractable ladders, and if you are sure footed and not afraid of heights, you can still visit some of these sites in the same way today.

To access Mesa Verde National Park, you drive up to the plateau along a winding road. People come from around the world to marvel at the natural beauty of the area (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)) as well as the archaeological remains, making it a popular tourist destination.

The twelfth- and thirteenth-century structures made of stone, mortar, and plaster remain the most intact. We often see traces of the people who constructed these buildings, such as hand or fingerprints in many of the mortar and plaster walls.

Ancestral Puebloans occupied the Mesa Verde region from about 450 CE to 1300 CE. The inhabited region encompassed a far larger geographic area than is defined now by the national park, and included other residential sites like Hovenweep National Monument and Yellow Jacket Pueblo. Not everyone lived in cliff dwellings. Yellow Jacket Pueblo was also much larger than any site at Mesa Verde. It had 600–1200 rooms, and 700 people likely lived there (see link below). In contrast, only about 125 people lived in Cliff Palace (largest of the Mesa Verde sites), but the cliff dwellings are certainly among the best-preserved buildings from this time.

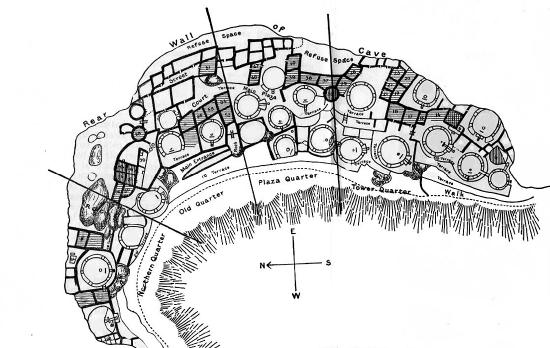

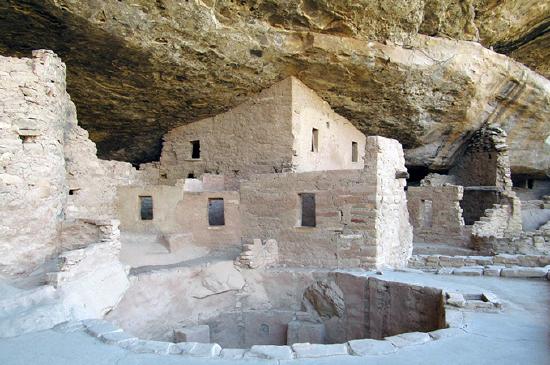

Cliff palace

The largest of all the cliff dwellings, Cliff Palace, has about 150 rooms and more than twenty circular rooms. Due to its location, it was well protected from the elements. The buildings ranged from one to four stories, and some hit the natural stone “ceiling.” To build these structures, people used stone and mud mortar, along with wooden beams adapted to the natural clefts in the cliff face. This building technique was a shift from earlier structures in the Mesa Verde area, which, prior to 1000 CE, had been made primarily of adobe (bricks made of clay, sand and straw or sticks). These stone and mortar buildings, along with the decorative elements and objects found inside them, provide important insights into the lives of the Ancestral Puebloan people during the thirteenth century.

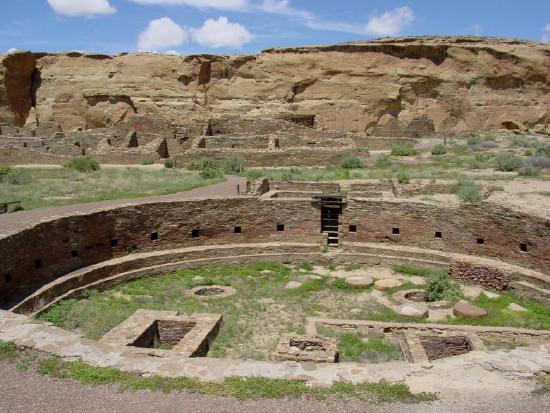

At sites like Cliff Palace, families lived in architectural units, organized around kivas (circular, subterranean rooms). A kiva typically had a wood-beamed roof held up by six engaged support columns made of masonry above a shelf-like banquette. Other typical features of a kiva include a firepit (or hearth), a ventilation shaft, a deflector (a low wall designed to prevent air drawn from the ventilation shaft from reaching the fire directly), and a sipapu, a small hole in the floor that is ceremonial in purpose. They developed from the pithouse, also a circular, subterranean room used as a living space.

Kivas continue to be used for ceremonies today by Puebloan peoples though not those within Mesa Verde National Park. In the past, these circular spaces were likely both ceremonial and residential. If you visit Cliff Palace, you will see the kivas without their roofs (see above), but in the past they would have been covered, and the space around them would have functioned as a small plaza.

Connected rooms fanned out around these plazas, creating a housing unit. One room, typically facing onto the plaza, contained a hearth. Family members most likely gathered here. Other rooms located off the hearth were most likely storage rooms, with just enough of an opening to squeeze your arm through a hole to grab anything you might need. Cliff Palace also features some unusual structures, including a circular tower. Archaeologists are still uncertain as to the exact use of the tower.

Painted murals

The builders of these structures plastered and painted murals, although what remains today is fairly fragmentary. Some murals display geometric designs, while other murals represent animals and plants.

For example, Mural 30, on the third floor of a rectangular “tower” (more accurately a room block) at Cliff Palace, is painted red against a white wall. The mural includes geometric shapes that are thought to portray the landscape. It is similar to murals inside of other cliff dwellings including Spruce Tree House and Balcony House. Scholars have suggested that the red band at the bottom symbolizes the earth while the lighter portion of the wall symbolizes the sky. The top of the red band, then, forms a kind of horizon line that separates the two. We recognize what look like triangular peaks, perhaps mountains on the horizon line. The rectangular element in the sky might relate to clouds, rain or to the sun and moon. The dotted lines might represent cracks in the earth.

The creators of the murals used paint produced from clay, organic materials, and minerals. For instance, the red color came from hematite (a red ocher). Blue pigment could be turquoise or azurite, while black was often derived from charcoal. Along with the complex architecture and mural painting, the Ancestral Puebloan peoples produced black-on-white ceramics and turquoise and shell jewelry (goods were imported from afar including shell and other types of pottery). Many of these high-quality objects and their materials demonstrate the close relationship these people had to the landscape. Notice, for example, how the geometric designs on the mugs in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)appear similar to those in Mural 30 at Cliff Palace.

Why build here?

From 500–1300 CE, Ancestral Puebloans who lived at Mesa Verde were sedentary farmers and cultivated beans, squash, and corn. Corn originally came from what is today Mexico at some point during the first millennium of the Common Era. Originally most farmers lived near their crops, but this shifted in the late 1100s when people began to live near sources of water, and often had to walk longer distances to their crops.

So why move up to the cliff alcoves at all, away from water and crops? Did the cliffs provide protection from invaders? Were they defensive or were there other issues at play? Did the rock ledges, as seen in Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\), have a ceremonial or spiritual significance? They certainly provide shade and protection from snow. Ultimately, we are left only with educated guesses—the exact reasons for building the cliff dwellings remain unknown to us.

Why were the cliffs abandoned?

The cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde were abandoned around 1300 CE. After all the time and effort it took to build these beautiful dwellings, why did people leave the area? Cliff Palace was built in the twelfth century, why was it abandoned less than a hundred years later? These questions have not been answered conclusively, though it is likely that the migration from this area was due to either drought, lack of resources, violence or some combination of these. We know, for instance, that droughts occurred from 1276 to 1299. These dry periods likely caused a shortage of food and may have resulted in confrontations as resources became more scarce. The cliff dwellings remain, though, as compelling examples of how the Ancestral Puebloans literally carved their existence into the rocky landscape of today’s southwestern United States.

Although the famed cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde were abandoned, it is important to note (and to combat misinformed lore and outdated rumors of collapse) that the Ancestral Puebloans did not vanish. Today’s present-day Puebloans are indeed the descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans. Recent studies have confirmed this scientifically using ancient DNA from the remains of domesticated turkeys. Studies demonstrated that the ancient Pueblo people had kept turkeys in both Mesa Verde, Colorado, and the northern Rio Grande area north of Santa Fe, New Mexico. DNA found in turkey bones at both locations definitively ties the mass exodus out of Mesa Verde to the northern Rio Grande area, currently inhabited by the Tewa Pueblo people.

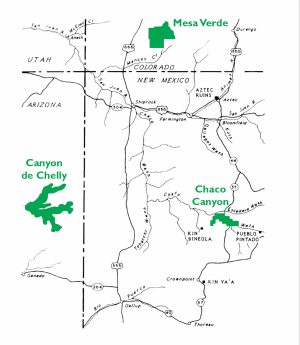

Introduction to Chaco Canyon

by Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank

New Mexico is known as the “land of enchantment.” Among its many wonders, Chaco Canyon stands out as one of the most spectacular. Part of Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Chaco Canyon is among the most impressive archaeological sites in the world, receiving tens of thousands of visitors each year. Chaco is more than just a tourist site however, it is also sacred land. Pueblo peoples like the Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni consider it a home of their ancestors.

The canyon is vast and contains an impressive number of structures—both big and small—testifying to the incredible creativity of the people who lived in the Four Corners region of the U.S. between the 9th and 12th centuries. Chaco was the urban center of a broader world, and the ancestral Puebloans who lived here engineered striking buildings, waterways, and more.

Chaco is located in a high, desert region of New Mexico, where water is scarce. The remains of dams, canals, and basins suggest that Chacoans spent a considerable amount of their energy and resources on the control of water in order to grow crops, such as corn. Today, visitors have to imagine the greenery that would have filled the canyon.

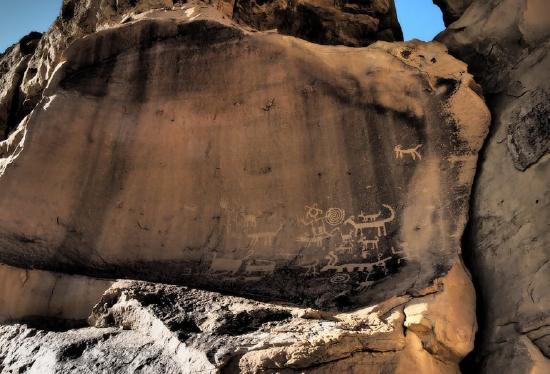

Astronomical observations clearly played an important role in Chaco life, and they likely had spiritual significance. Petroglyphs found in Chaco Canyon and the surrounding area reveal an interest in lunar and solar cycles, and many buildings are oriented to align with winter and summer solstices.

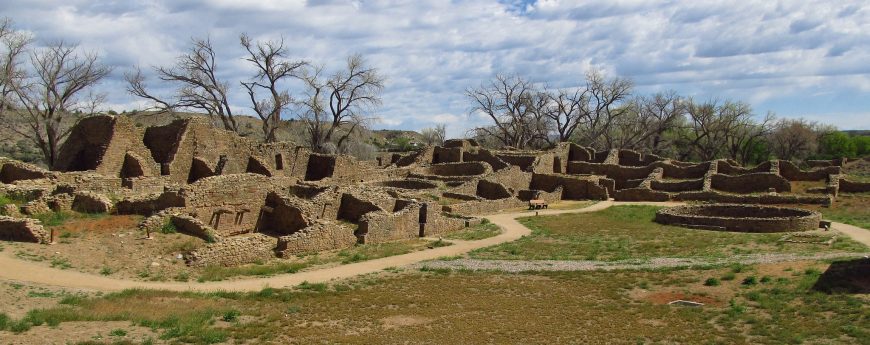

Great Houses

“Downtown Chaco” features a number of “Great Houses” built of stone and wood. Most of these large complexes have Spanish names, given to them during expeditions, such as one sponsored by the U.S. army in 1849, led by Lt. James Simpson. Carabajal, Simpson’s guide, was Mexican, which helps to explain some of the Spanish names. Great Houses also have Navajo names, and are described in Navajo legends. Tsebida’t’ini’ani (Navajo for “covered hole”), nastl’a kin (Navajo for “house in the corner”), and Chetro Ketl (a name of unknown origin) all refer to one great house (shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\)), while Pueblo Bonito (Spanish for “pretty village”) and tse biyaa anii-ahi (Navajo for “leaning rock gap”) refer to another.

Pueblo Bonito is among the most impressive of the Great Houses. It is a massive D-shaped structure that had somewhere between 600 and 800 rooms. It was multi-storied, with some sections reaching as high as four stories. Some upper floors contained balconies.

There are many questions that we are still trying to answer about this remarkable site and the people who lived here. A Great House like Pueblo Bonito includes numerous round rooms, called kivas. This large architectural structure included three great kivas and thirty-two smaller kivas. Great kivas are far larger in scale than the others, and were possibly used to gather hundreds of people together. The smaller kivas likely functioned as ceremonial spaces, although they were likely multi-purpose rooms.

Among the many remarkable features of this building are its doorways, sometimes aligned to give the impression that you can see all the way through the building, as in Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\). Some doorways have a T shape, and T-shaped doors are also found at other sites across the region. Research is ongoing to determine whether the T-shaped doors suggest the influence of Chaco or if the T-shaped door was a common aesthetic feature in this area, which the Chacoans then adopted.

Recently, testing of the trees (dendroprovenance) that were used to construct these massive buildings has demonstrated that the wood came from two distinct areas more than 50 miles away: one in the San Mateo Mountains, the other the Chuska Mountains. About 240,000 trees would have been used for one of the larger Great Houses.

Chacoan Cultural Interactions

Traditionally, we tend to separate Mesoamerica and the American Southwest, as if the peoples who lived in these areas did not interact. We now know this is misleading, and was not the case.

Chacoan culture expanded far beyond the confines of Chaco Canyon. Staircases leading out of the canyon allowed people to climb the mesas and access a vast network of roads that connected places across great distances, such as Great Houses in the wider region. Aztec Ruins National Monument (not to be confused with ruins that belonged to the Aztecs of Mesoamerica) in New Mexico is another ancestral Puebloan site with many of the same architectural features we see at Chaco, including a Great House and T-shaped doorways.

Archaeological excavations have uncovered remarkable objects that animated Chacoan life and reveal Chaco’s interactions with peoples outside the Southwestern United States. More than 15,000 artifacts have been unearthed during different excavations at Pueblo Bonito alone, making it one of the best understood spaces at Chaco. Many of these objects speak to the larger Chacoan world, as well as Chaco’s interactions with cultures farther away. In one storage room within Pueblo Bonito, pottery sherds had traces of cacao imported from Mesoamerica. These black-and-white cylindrical vessels were likely used for drinking cacao, similar to the brightly painted Maya vessels used for a similar purpose.

The remains of scarlet macaws, birds native to an area in Mexico more than 1,000 miles away, also reveal the trade networks that existed across the Mesoamerican and Southwestern world. We know from other archaeological sites in the southwest that there were attempts to breed these colorful birds, no doubt in order to use their colorful feathers as status symbols or for ceremonial purposes. A room with a thick layer of guano (bird excrement) suggests that an aviary also existed within Pueblo Bonito. Copper bells found at Chaco also come from much further south in Mexico, once again testifying to the flourishing trade networks at this time. Chaco likely acquired these materials and objects in exchange for turquoise from their own area, examples of which can be found as far south as the Yucatan Peninsula.

Current Threats to Chaco

The world of Chaco is threatened by oil drilling and fracking. After President Theodore Roosevelt passed the Antiquities Act of 1906, Chaco was one of the first sites to be made a national monument. Chaco Canyon is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Chacoan region extended far beyond this center, but unfortunately the Greater Chacoan Region does not fall under the protection of the National Park Service or UNESCO. Much of the Greater Chaco Region needs to be surveyed, because there are certainly many undiscovered structures, roads, and other findings that would help us learn more about this important culture. Beyond its importance as an extraordinary site of global cultural heritage, Chaco has sacred and ancestral significance for many Native Americans. Destruction of the Greater Chaco Region erases an important connection to the ancestral past of Native peoples, and to the present and future that belongs to all of us.

Articles in this section:

- Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “About geography and chronological periods in Native American art,” in Smarthistory, September 16, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “Terms and Issues in Native American Art,” in Smarthistory, September 16, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Katherine T. Brown, “Fort Ancient Culture: Great Serpent Mound,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- David W. Penney, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution and Beth Harris, "Mississippian shell neck ornament (gorget)," in Smarthistory, January 13, 2018 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “Mesa Verde,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “Introduction to Chaco Canyon,” in Smarthistory, April 13, 2018 (CC BY-NC-SA)