4.3: South America (Nasca, Paracas, Moche)

- Page ID

- 108709

Introduction to Andean Cultures

by Dr. Sarahh Scher

A land of contrasts

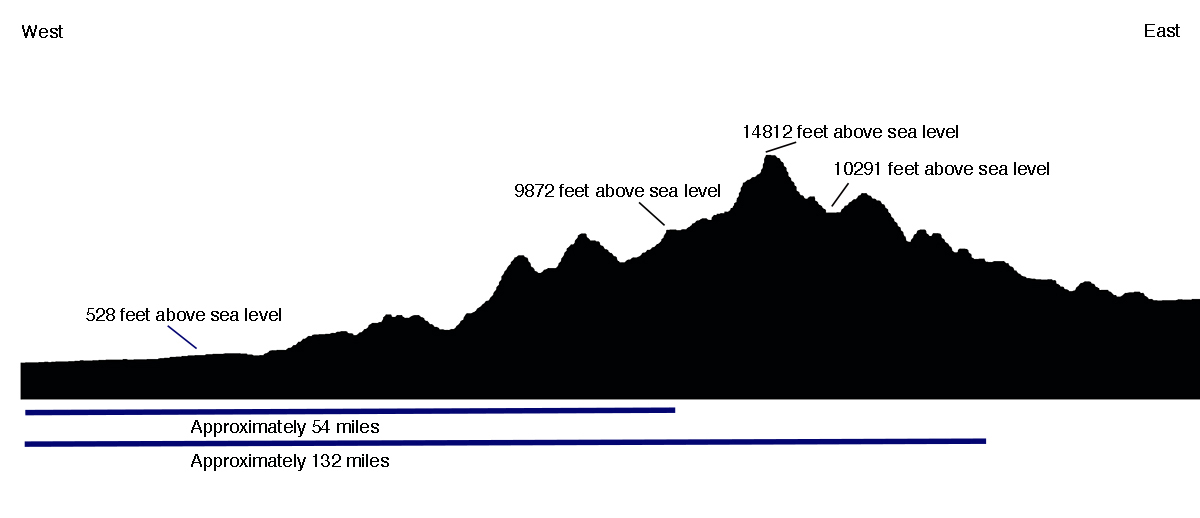

“The Andes” can refer to the mountain range that stretches along the west coast of South America, but is also used to refer to a broader geographic area that includes the coastal deserts to the west and into the tropical jungles to the east of those mountains. This region is seen as home to a distinct cultural area—dating from around the fourth millennium BCE to the time of the Spanish conquest—and many of these cultures still persist today in various forms.

From the desert coast, the mountains rise up quickly, sometimes within 10-20 kilometers of the Pacific Ocean. Therefore, the people who lived in the Andes had to adapt to varying types of climate and ecosystems. This diverse environment gave rise to a range of architectural and artistic practices.

| Period and time scale | North Coast |

Central Coast |

South Coast |

North Highlands |

Central Highlands |

South Highlands |

Titicaca region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formative 3500-900 BCE |

Cerro Sechin Huaca Prieta |

Kotosh Guitarrero |

Chinchorros | ||||

| Early Horizon 900-100 BCE |

Cupisnique | Paracas | Chavín | Pukará | |||

| Early Intermediate Period 100 BCE-600 BCE |

Moche Gallinazo |

Nasca | REcuay | Tiwanaku | |||

| Middle Horizon 600-1000 CE |

Sicán Moche |

Wari | Wari | Wari | Wari | Tiwanaku | |

| Late Intermediate Period 1000-1438 CE |

Chimú Sicán |

Chancay | Ica | ||||

| Late Horizon 1428-1532 |

Inka | Inka | Inka | Inka | Inka | Inka | Inka |

Deserts, mountains, and farms

Though much of the Andean coast is near the Equator, its waters are cold, due to currents from the Antarctic. This cold water is rich in sea life; however, during El Niño years, warm water takes over, leading to large die-offs of fish and marine mammals, and often creating catastrophic flooding on the coast.

In normal years, the coast is very dry. The rivers that run to the coast, fed by melting snow from the Andes mountains (called the Cordillera Blanca, or White Mountains, in contrast to the Cordillera Negra, or Black Mountains to the west where snow does not fall), create areas of agricultural lands interspersed with desert. Cultures eventually learned to create canals, allowing them to irrigate more land, and irrigation remains important to farming on Peru’s coast.

As the elevation climbs, different ecological zones are created, and people of the Andes used these to grow different products: maize (corn), hot peppers, potatoes, and coca all grew at different elevations. Some cultures (such as the Cupisnique and Paracas ) developed on the coast, and incorporated seafood into their diet. They would trade with the cultures that lived in the highlands (such as the Recuay and the inhabitants of Chavín de Huantar ) for the things they could not grow for themselves. The people in the highlands would likewise trade with the coastal peoples for dried fish and products that would not grow at their elevation, as well as exotic animals like parrots from the tropical jungles to the east.

Plants and animals

The plants and animals of the Andes provided ancient peoples with food, medicine, clothing, heat, and many other resources for daily life. As noted above, the rapid change in elevation of the Andes meant that many different foods could be grown in a compressed area. Potatoes were a staple food of the highlands, and maize and manioc were important in the lower elevations.

Coca grew in the highlands but was traded all over the Andes. The leaves of this plant, when chewed, provide a stimulant that allows people to walk for long periods at high altitude without getting tired, and it suppresses hunger. It was used by travelers in the highlands, but was also used in ritual practices to endure long nights of dancing. In modern times, people drink it as a tea to help with the symptoms of altitude sickness.

Farming in the steep topography of the mountains could be difficult, and an important innovation developed by the Andeans was the use of terracing. By creating terraces (essentially giant steps along the contours of a mountain) people were able to make flat, easily worked plots. The terraces were formed by creating retaining walls that were then backfilled with a thick layer of loose stones to aid drainage, and topped with soil.

The most important animals in the highlands were camelids: the wild vicuña and guanaco, and their domesticated relatives, the llama and alpaca. Alpacas have soft wool and were sheared to make textiles, and llamas can carry burdens over the difficult terrain of the mountains (an adult male llama can carry up to 100 pounds, but could not carry an adult human).

Both animals were also used for their meat, and their dried dung served as fuel in the high altitudes, where there was no wood to burn. Andean camelids, like their African and Asian cousins, can be very headstrong. If they are overloaded, they will sit on the ground and refuse to budge. Because of this, the ancient people of the Andes did not have domesticated animals that could carry them or pull heavy wagons, and so roads and methods of moving people and goods developed differently than in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The wheel was known, but not used for transport, because it simply would not have been useful.

Textile arts

The ancient peoples of the Andes developed textile technology before ceramics or metallurgy. Textile fragments found at Guitarrero Cave date from c. 5780 BCE. Over the course of millennia, techniques developed from simple twining to complex woven fabrics. By the first millennium CE, Andean weavers had developed and mastered every major technique, including double-faced cloth and lace-like open weaves.

Andean textiles were first made using fibers from reeds, but quickly moved to yarn made from cotton and camelid fibers. Cotton grows on the coast, and was cultivated by ancient Andeans in several colors, including white, several shades of brown, and a soft grayish blue. In the highlands, the alpaca provided soft, strong wool in natural colors of white, brown, and black. Both cotton and wool were also dyed to create more colors: red from cochineal, blue from indigo, and other colors from plants that grew at various elevations. Alpaca wool is much easier to dye than cotton, and so it was usually preferred for coloring. The extra time and effort needed to dye fibers made the bright colors a symbol of status and wealth throughout Andean history.

Ceramics

Though ceramics were not as valuable as textiles to Andean peoples, they were important for spreading religious ideas and showing status. People used plain everyday wares for cooking and storing foods. Elites often used finely made ceramic vessels for eating and drinking, and vessels decorated with images of gods or spiritually important creatures were kept as status symbols, or given as gifts to people of lesser status to cement their social obligations to those above them.

There are a wide variety of Andean ceramic styles, but there are some basic elements that can be found throughout the region’s history. Wares were mostly fired in an oxygenating atmosphere, resulting in ceramics that often had a red cast from the clay’s iron content. Some cultures, such as the Sicán and Chimú, instead used kilns that deprived the clay of oxygen as it fired, resulting in a surface ranging from brown to black.

Decoration of ceramics could be done by incising lines into the surface, creating textures by rocking seashells over the damp clay, or by painting the surface.

Some early elite ceramics were decorated after firing with a paint made from plant resin and mineral pigments. This produced a wide variety of bright colors, but the resin could not withstand being heated and so these resin-painted wares were only for display and ritual use. Most ceramics in the Andes instead were slip-painted. Slip is a liquid that is made of clay, and the color of the slip is determined by the color of the clay and its mineral content. Most slip painting was applied before firing, after the semi-dry clay had been burnished with a smooth stone to prepare the surface. The range of slip colors could vary from two (seen in Moche ceramics) to seven or more (seen in Nasca ceramics). Once fired, the burnished surface would be shiny. Ceramics, because of their durability, are one of the greatest resources for understanding ancient Andean cultures.

Metalwork

Metalworking developed later in Andean history, with the oldest known gold artifact dating to 2100 BCE, and evidence of copper smelting from around 900–700 BCE. Gold was used for jewelry and other forms of ornamentation, as well as for making sculptural pieces. Inka figurines of silver and gold depicting humans and llamas have been recovered from high-altitude archaeological sites in Peru and Chile. Copper and bronze were also used to create jewelry and items like ceremonial knives (called tumis).

Architecture

The architecture of the Andes can be divided roughly between highland and coastal traditions. Coastal cultures tended to build using adobe, while highland cultures depended more on stone. However, the lowland site of Caral, which is currently the oldest complex site known in the Andes, was built mainly using stone.

Beginning with Caral in 2800 BCE, various cultures constructed monumental structures such as platforms, temples, and walled compounds. These structures were the focus of political and/or religious power, like the site of Chavín de Huantár in the highlands or the Huacas de Moche on the coast. Many of these structures have been heavily damaged by time, but some reliefs and murals used to decorate them survive.

The best-known architecture in the Andes is that of the Inka . The Inka used stone for all of their important structures, and developed a technique that helped protect the structures from earthquakes. Because of its stone construction, Inka architecture has survived more easily than the adobe architecture of the coast. Ongoing efforts by archaeologists and the Peruvian Ministry of Culture are also focused on restoring and preserving the great works of coastal architecture.

Ancient past, continuing traditions

From textiles to ceramics, metalwork, and architecture, Andean cultures produced art and architecture that responded to their natural environment and reflected their beliefs and social structures. We can learn much about these ancient traditions through the artifacts and sites that survive, as well as the many ways that these practices—such as weaving—persist today.

Nasca Geoglyphs

by Jayne Yantz

Located in the desert on the South Coast of Peru, the Nasca Geoglyphs are among the world’s largest drawings. Also referred to as the Nasca Lines, they are more accurately called geoglyphs, which are designs formed on the earth. Geoglyphs are usually constructed from strong natural material, such as stone, and are notably large in scale.

Imagine encountering such a drawing. The hummingbird measures over 300 feet in length, and is one of the most famous Nasca Geoglyphs. Among the other celebrated geoglyphs of mammals, birds and insects are a monkey, killer whale, spider, and condor. Various plants, geometric shapes (spirals, zigzag lines and trapezoids), abstract patterns, and intersecting lines fill the desert plain, known as the Pampa, an area covering approximately 200 square miles near the foothills of the Andes. The zoomorphic geoglyphs are the oldest and most esteemed. Each appears to have been made with a single continuous line.

Today it is believed that the geoglyphs were created by the Nasca people, whose culture flourished in Peru sometime between 1-700 CE. They inhabited the river valleys of the Rio Grande de Nasca and the Ica Valley in the southern region of Peru, where they were able to farm, despite the desert environment—one of the driest regions in the world. The high Andes Mountains to the east prevent moisture from the Amazon from reaching the coast, so there is very little rainfall; water that does arrive, comes from mountain runoff.

The Nasca people are also famous for their polychrome pottery, which shares some of the same subjects that appear in the Nasca Geoglyphs. Remains of Nasca pottery left as offerings have been found in and near the geoglyphs, cementing the connection between the geoglyphs and the Nasca people. Because the quality of the ceramics produced in Nasca is very high, archaeologists deduce that specialists shaped and painted the pottery vessels. This suggests a society that, at its height, had a degree of wealth and a division of labor. However, the Nasca people had no writing. In cultures without writing, images often assume an increased level of importance. This may help explain why the Nasca came together to create vast images on the desert floor.

How were they made?

Since the Nasca geoglyphs are so large, it seems clear they were constructed by organized groups of people and that no single artist made them. The construction of the geoglyphs are thought to represent organized labor where a small group of individuals directed the design and creation of the lines, a process that may have strengthened the social unity of the community. Despite the impressive scale of the geoglyphs, these remarkable works did not require complex technology. Most geoglyphs were formed by removing weathered stones from the desert floor, stones that had developed a dark patina known as “desert varnish” on their surface. Once removed, the lighter stones below became visible, forming the famous Nasca Lines. The extracted darker stones were placed at the edges of the lines, forming a border that accented the lighter lines within. Straight lines could be created by extending cords, one on each side of the line, between two wooden stakes (some of which have been recovered) that guided workers and allowed for the creation of sight lines.

For larger geometric shapes, such as trapezoids, borders were marked and then all the stones on the interior were removed and placed along edges or heaped in piles at the edges of the geoglyph. Broken pottery has been found mixed with the piles of stones. Spirals and animal shapes were made in a similar manner. Spirals, for example, would be formed by releasing slack in a cord as workers moved around in a circular path, moving further and further from the center where the spiraling line begins. For animal forms, such as monkeys, whales, or hummingbirds, portions of the figures might be made in the same manner as the spiral in the monkey’s tail, or the image might be based on a gridded drawing or textile model that was enlarged on the desert floor where lines were staked out to create the figure.

When were they made?

The oldest of the Nasca Geoglyphs is more than 2000 years of old, but, as a group, the Nasca geoglyphs were created over several centuries, with some later lines or shapes intersecting or overlapping with previously created lines. This is just one of the unusual features of these geoglyphs. Even more curious, the drawings are best observed from the air, which is why they did not become widely known until the 1920s after the development of flight. Although it is possible to observe some of the lines from the adjacent Andean foothills or the modern mirador (viewing platform), the best way to see the lines today remains a flight in a small plane over the Pampa (lowlands). These amazing images are so large that they cannot be truly appreciated from the ground. This, of course, raises the question: for whom were the lines made? And, what was their purpose?

What was their purpose and meaning?

Archaeologists are not certain of the purpose of the lines, or even of the audience for whom the lines were intended since they can only be seen clearly from the air (This is now particularly true of the older animal designs). Were they made to be seen by deities looking down from the heavens or from distant mountain tops? Perhaps the numerous theories that have been proposed will eventually be clarified as our understanding of the cultures of ancient Peru increases.

Celestial alignments?

Shortly after the geoglyphs were first investigated, researchers sought an astronomical interpretation, suggesting that the geoglyphs might be aligned with the heavens, and perhaps represented constellations or marked the solstices or planetary trajectories. While some geoglyphs seem connected to celestial events, such as marking the summer solstice (in December) when mountain waters flow to the coast, it is difficult to find celestial alignments for most of the geoglyphs. As far as we know, Andean peoples did not form pictures by connecting the stars in the night sky as we do; rather they looked at the black spaces between stars and saw shapes that they converted into their own reverse “constellations.” It is important to note that these constellations do not seem to match the Nasca geoglyphs.

Deities or ceremonial walkways?

Many other reasonable theories have been proposed. Some scholars have suggested that the geoglyphs represent Nasca deities, or formed a calendar for farming, or represented ceremonial walkways. Because some of the lines do seem to direct people to Cahuachi, a Nasca religious center and pilgrimage destination, it seems possible that ancient Nasca people walked the lines. It is also possible that Nasca people ritually danced on the lines, perhaps in connection with shamanism and the use of hallucinogens. The geoglyphs, particularly the early animals which are clearly spaced apart from each other, may also have strengthened group identity and reinforced social interaction patterns as individual groups of people may each have tended or “owned” one of the geoglyphs,

A discredited theory proposed that the geoglyphs are the result of alien contact. While this is sensationalist and helped to secure the popular fame of the Nasca geoglyphs, there is no evidence to support this assertion. Archaeologists and scientists have rejected this proposal and it is important to recognize the implication of this theory is that the Nasca people needed the influence of aliens peoples to create their geoglyphs. We know that the technology to manufacture the geoglyphs was available to the Nasca people and that they had a social system that was fully capable of organizing and producing large geoglyphs. We also know that the designs are consistent with other art forms native to Nasca culture.

Farming, fertility, and water?

Among the most promising recent theories, archaeologists have begun to secure a link between the geoglyphs and farming, which sustained the Nasca people. Some geoglyphs may deal with fertility for crops; others may be associated with the water needed to raise the crops. In a desert, water is the most important commodity. In Andean mythology the mountains are revered as the home of the gods. It has been suggested that the lines were intended to be visible to the gods in the mountains. Some lines also seem to point in the direction of the mountains — the origin of fresh water for the desert South Coast of Peru. Snow pack melts high in the mountains and becomes runoff and a vital source of water for the coast. In fact, ancient underground water channels are sometimes marked on the surface by Nasca geoglyphs, particularly at the points of intersection. These have been dubbed “ray centers,” spots where lines converge. Offerings have been found at these points, including conch shells. The spirals on the desert floor, in the monkey’s tail, and as independent abstract designs, may refer to the spirals found in conch shells and thus may reference water. This same shape appears in Nasca puquios —gradually descending tunnels that tap ancient subterranean aquifers and water channels. Puquios have been described as wells, and formed part of this ancient irrigation system. Puquios, found in Nasca (and elsewhere in Peru), allowed people to reach water in times of drought. Geoglyphs other than spirals may also be directly associated with water.

Preservation

Because the Nasca Geoglyphs were made directly on the earth by rearranging stones on the desert floor, these giant images are actually quite vulnerable to damage. In time the lighter-colored stones exposed by the Nasca people may attain their own patina, making them less visible, but the designs face greater threats from vehicle and pedestrian traffic. Crossing the lines can damage their borders and make the images less distinct. Because of this, the Peruvian government has created a mirador (viewing platform) along the Pan American Highway where visitors can climb to view a few drawings without damaging the lines.

In the end, it is likely that the Nasca Geoglyphs served more than one purpose, and these purposes may have changed over the centuries, especially given that new lines often “erased” older ones by “drawing” over them. It does appear that many geoglyphs made reference to water and agricultural fertility, and were used to promote the welfare of the Nasca people. The geoglyphs were also a place where people gathered, perhaps for pilgrimage, perhaps to walk or dance on the lines in a ritual pattern. As a gathering place, the Nasca geoglyphs may additionally have turned the Pampa into a map of social divisions, where different families or clans tended different geoglyphs. Although we do not know exact details, we can surmise that the geoglyphs represent a community investment meant to serve this ancient people.

Backstory (by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee)

In January, 2018, a semi truck traveling through Peru on the Pan-American highway veered off the road and plowed through the desert. The deep ruts that it made damaged several of the Nasca lines. Though the area is clearly marked as a protected zone, according to the archeologist Johnny Isla , co-director of the Nasca-Palpa Project, cases like this “occur daily.” The driver, who authorities suspect may have been trying to avoid a toll, was charged with an “attack against cultural heritage.”

Human interventions like this constitute the main threat to the Nasca-Palpa area, whose geoglyphs extend across almost 300 square miles. In 2014, Greenpeace activists damaged the desert floor around the famous hummingbird geoglyph as they lay out a large protest sign meant to be seen from the air. Their action was a protest against climate change during the United Nations summit in Lima, and was not intended to damage the site; the organization has since apologized. However, the marks made by the activists’ footprints have been deemed possibly “irreparable” by Luis Jaime Castillo Butters, a professor of archeology and Peru’s Vice Minister for Cultural Heritage. “A bad step, a heavy step … marks the ground forever,” he said . “There is no known technique to restore it the way it was.”

The construction of the Pan-American highway has also increased the risks to the area, not only because of vehicles that can potentially veer off the road, but also because rains and mud can wash off of the surface and damage the lines .

Nasca-Palpa was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. In contrast to many other at-risk heritage sites around the world, UNESCO states that

Even though there have been some impacts caused by natural and human factors, these have been minimal and the geoglyphs maintain their authenticity and express their high symbolic and historic value even today.

The most pressing need, now being discussed by Isla and others, is for better, 24-hour monitoring of the area — possibly using drone technology — so that human incursions on the site can be quickly addressed and avoided.

The Paracas Textile

by Lois Martin

Mummy bundles

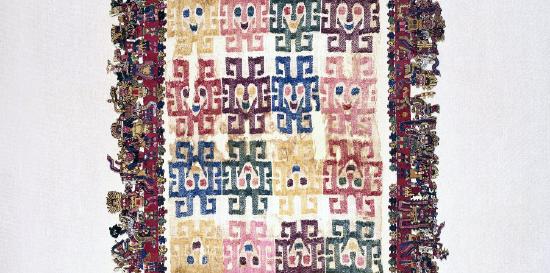

One of the most extraordinary masterpieces of the pre-Columbian Americas is a nearly 2,000-year-old cloth from the South Coast of Peru, which has been in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art since 1938.

Despite the textile’s small size (it measures about two by five feet), it contains a vast amount of information about the people who lived in ancient Peru; and despite its great age and delicacy, its colors are brilliant, and tiny details amazingly intact. This is due to the arid environment of southern Peru along the Pacific shore, where it is so dry that organic material buried in the sand remains well preserved for hundreds or even thousands of years.

In the ancient cemeteries on the Paracas Peninsula, the dead were wrapped in layers of cloth and clothing into “mummy bundles.” The largest and richest mummy bundles contained hundreds of brightly embroidered textiles, feathered costumes, and fine jewelry, interspersed with food offerings, such as beans. Early reports claimed that this cloth came from the Paracas peninsula, so it was called “THE Paracas textile,” to mark its excellence and uniqueness. Currently, scholars have revised this provenance, and now attribute the cloth to the related, but slightly later Nasca culture.

Thread by thread

Recently, the Brooklyn Museum has posted high quality, close-up views of this masterpiece online, allowing viewers to scrutinize the textile, thread by thread. Such a detailed inspection has not been possible since the piece was first made. With simple tools, the early cultures of the Andean region of South America produced textiles of astonishing virtuosity. Some extremely fine pieces, like this one, are too delicate to have served any utilitarian purpose, and so are considered ceremonial.

Like some other very fine cloths, the Brooklyn textile is finished so carefully on both sides that it is almost impossible to distinguish which is the correct side. Although the central cloth and its framing dimensional border are created by different techniques, both display perfect reversibility—except for three border figures. These three—instead of being duplicated on the back (as if flipped in mirror image), like all the others—appear in back view on one side of the cloth, thereby designating a “front” and “back” to the textile.

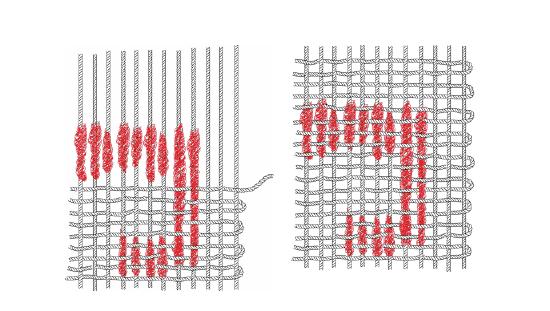

The central cloth’s design of 32 geometric faces is created by “warp-wrapping,” a technique in which colored fleece is wound around sections of cotton warp threads before weaving.

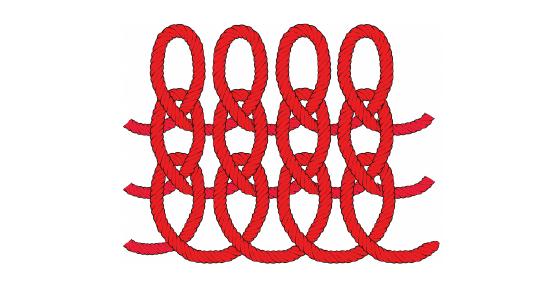

Because the central cloth and the border have different color palettes, they may have been created at different times. The triple-layer border has colorful outer veneers of wool “crossed-looping” that envelop inner cotton cores of looping or weaving.

“Crossed-looping” resembles knitting (but is accomplished with a single needle); in areas where the threads are broken, it is possible to glimpse the underlying cotton substrates. While the cotton is off-white, the wool is dyed in jewel-bright tones. The combination of materials suggests extensive trading relationships: for while cotton was grown in coastal valleys, wool came from camelids (such as the llama, alpaca, and vicuña) that live at high altitudes in the Andes mountains.

Monstrous hybrids

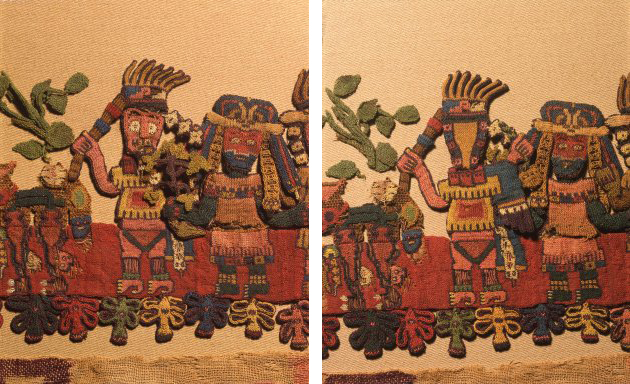

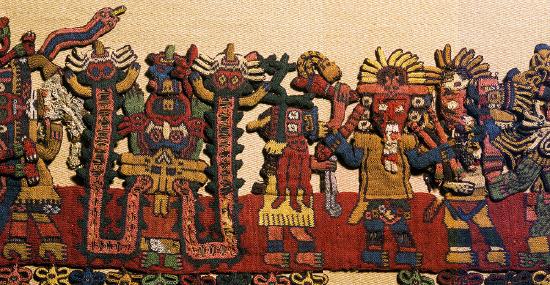

On the border, a parade of 90 figures is linked together on their lower bodies, which are worked two-dimensionally against a red background.

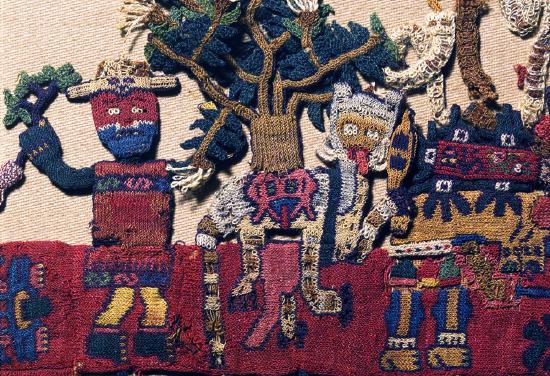

Each figure’s upper body and head is constructed as a separate unit, and attached to the woven strip. The upper bodies are worked in bas-relief, with some parts projecting outwards from the plane of the fabric. Tiny components (like leaves and feathers) were worked as separate pieces and then attached, giving a wonderful three-dimensionality and liveliness to the figures, especially because they mingle and overlap.

The parade is arranged in four, single-file, L-shaped lines that proceed around each corner of the cloth. A wide variety of types appear, including human, animal, and monstrous hybrids. Some figures are unique, others are twins, triplets, or even sextuplets; a few are in related groups.

Most of the animals and plants that appear can be tied to species still found on the South Coast, and many human figures wear or carry items that directly relate to the archaeological record.

Their jewelry, for example, corresponds to specimens formed from thin sheets of gleaming gold. These include: “forehead ornaments” (shaped like a bird with outstretched wings); “hair spangles” (disk or star shapes that dangle from the wingtips of the forehead ornament); slender, feather-shaped headdress “plumes;” and “mouthmasks.” Mouthmasks hung from the nose septum, and had flaring extensions, like cat whiskers.

Garments

The border figures’ clothing also matches examples found archaeologically, and some bear minuscule designs that faithfully represent embroidered decorations found on life-sized garments. Some wear wrap-around dresses of a style worn by women in ancient times; others wear two-part outfits, associated with men (Figure \(\PageIndex{35}\)). The largest and most beautifully decorated garments were mantles that draped over the shoulders, and fell to the knee. By examining stitches on actual mantles, archaeologists have determined that teams of artists worked on them, sitting side-by-side.

Other border details, rather than realistic, seem to be fantastic or mythological. The severed heads (sometimes called “trophy heads”) brandished by some figures, for example, sometimes sprout flourishing plants—as if to suggest themes of sacrifice and fertility. And snake-like streamers that flow from some figures do not correspond to any known object, and may indicate supernatural qualities.

When they depicted clothing, Paracas and Nazca artists often added a face, or an animal body to the loose ends of fabric hanging behind a wearer. This artistic convention seems to suggest the lively movements of cloth fluttering behind a wearer, and hints that these ancient people considered cloth a precious carrier of vitality: an interpretation that seems warranted because this vibrant textile gives us such an evocative and animated glimpse into their world.

Backstory (by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee)

The Paracas Textile is only one of hundreds of similar textiles that originate from multiple burial sites on the Paracas peninsula. These burials were first identified and excavated by the renowned Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello in the 1920s. For political reasons, Tello was forced to abandon the site in 1930, and, without a team of archaeologists to oversee the area, a period of intense looting followed. It is now believed that a great number of the Paracas textiles in international museum collections were acquired as a result of this looting, which occurred most heavily between 1931 and 1933.

A large group of these illegally acquired textiles is held by the Gothenburg Collection in the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden. The objects were smuggled out of Peru by the Swedish consul in the early 1930s, and donated to the city of Gothenburg. The museum and city fully acknowledge the objects’ illicit provenance, and have been working with the Peruvian government on a plan for their systematic return. As stated on the museum website,

Large quantities of Paracas textiles were illegally exported to museums and private collections all over the world between 1931 and 1933. About a hundred of these were taken to Sweden and donated to the Ethnographic Department of Gothenburg Museum. Today, problems associated with looted artifacts and illicit trade in antiques are better acknowledged and being addressed.

Though Peru began lobbying for repatriation in 2009, Gothenburg has been somewhat slow to respond to the requests, partly due to the fragile condition of the textiles. According to the museum website, even the transport of these objects between the museum’s archives and their exhibition space in Sweden—a distance of only a few kilometers—has resulted in their deterioration. Despite these concerns, a plan has been put in place to systematically return some of the textiles to Peru. The first four were delivered in 2014, and another 79 in 2017. Further works are set to be returned by 2021. The repatriated textiles are now in the possession of Peru’s General Directorate of Museums of the Ministry of Culture.

The case of the Gothenburg Paracas textiles highlights the need not only for governmental and institutional agreements regarding the restitution of illegally acquired objects, but also for oversight concerning the continued stewardship and preservation of these fragile artworks.

Moche culture, an introduction

by Dr. Sarahh Scher

Moche architects and artists raised spectacular adobe platforms and pyramids, and created exquisite ceramics and jewelry. Their art, unlike that of most Andean cultures, is naturalistic and rich in imagery, inviting us to explore their world.

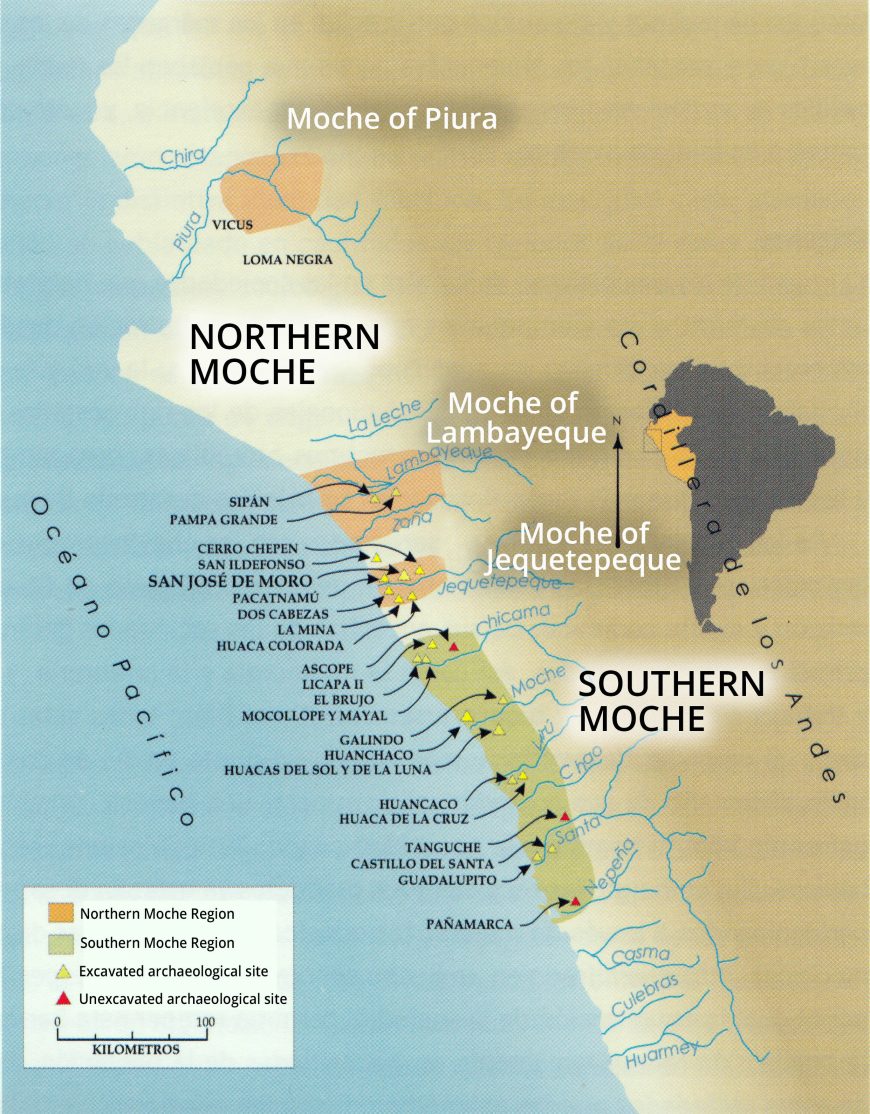

The Moche culture thrived on Peru’s northern coast between approximately 200 and 900 CE. Rising and falling long before the Inka, the culture left no written records, and the early Spanish colonists who chronicled the cultures of Peru found the Chimú people in what had earlier been Moche territory. The Moche are a prime example of how archaeologists and art historians use scientific methods of data collection and evaluation in understanding ancient, non-literate cultures.

In the early 20th century, there was very little scientific excavation in Peru. Many art objects that came into museums and private collections were taken from graves and had no record of their original context. Based on this limited knowledge, scholars thought that the Moche had been a unified state that held sway over a large swath of the north coast, from near the border with modern-day Ecuador in the north to the Huarmey river valley to the south (Huarmey is approximately 180 miles north of the modern capital city of Lima). This conclusion was based on the similarity of ceramic and metal artworks being found throughout the range.

Not a single unified political entity

As modern scientific archaeology began in the area, it became clear that the Moche were not a single, unified political entity. Archaeologists and art historians began to see that differences in style and iconography could be determined between areas. Architectural structures were different at different sites. In addition, carbon dating allowed scholars to understand that some styles of pottery could be from one time frame in one river valley, while being associated with a completely different time frame in another. As more data was accumulated, hypotheses were tested and the conception of the Moche was revised and reassessed. What emerged was a vision of the Moche as politically independent groups who shared a common ideology, mythical and religious beliefs and practices, as well as a common iconography for their artwork.

Independent areas (sometimes as large as a pair of river valleys, sometimes as small as one section of a single valley) would signal that they belonged to Moche culture by using Moche themes in their artwork, while at the same time asserting differences—in architecture, in iconographic style, and in which figures from the mythology were deemed important. In this way, separate Moche polities could express both their political independence as well as their sense of belonging to a larger cultural system. The biggest separation of Moche style and iconography splits them into northern and southern areas (see Figure \(\PageIndex{39}\)), which can then be subdivided into smaller, politically independent areas.

North-South Differences

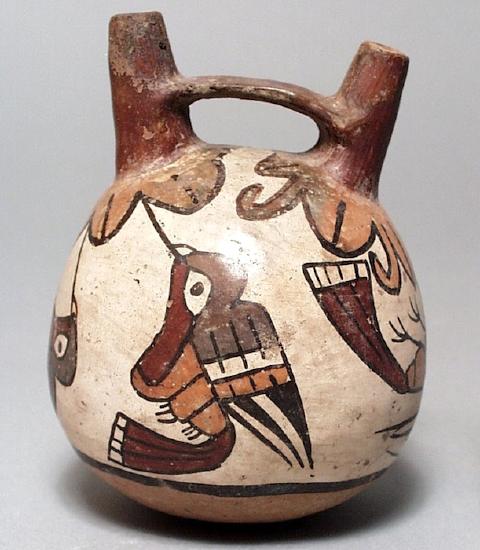

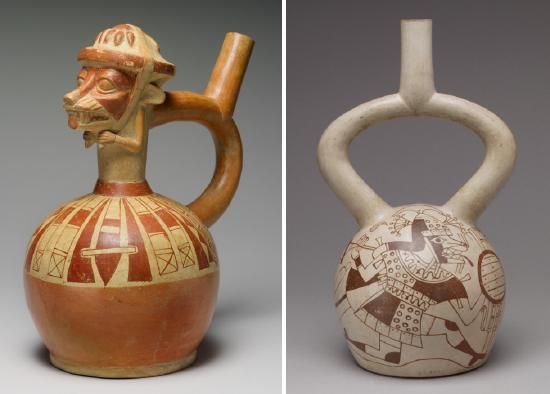

The Southern Moche tended to be expert ceramicists—producing a large amount of fine, thin-walled vessels painted in slip. Moche artists used only three colors—cream, red-brown or red-orange, and black to decorate their ceramics. Many Moche ceramics were made using molds, and so we have many duplicate pieces. The ability to control imagery through the use of molds seems to have been important to the political elites of the Moche.

Early Moche vessels are very sculptural, depicting humans, supernatural figures, animals, and plants in a great variety. Later Moche ceramics feature complex line drawings of similar subject matter (called fineline style). The Moche often used a distinctive spout on their vessels, called a stirrup spout. It is composed of a hollow tube of clay bent into an upside-down U shape, with another tube piercing it at the apex of the curve (see images below). This spout form has ancient origins in the Andes, and it seems possible that the Moche deliberately chose this form to echo its use in during the earlier Cupisnique (1500-500 BCE) and Chavín (900-200 BCE) cultures. Fine ceramics would have been used as gifts from the highest elites to the lower elites and middle classes, helping to cement the social bonds that supported the power that the elites held. Fine ceramics have been found in households, and the pieces in graves show evidence that they had been used.

The Northern Moche are celebrated for their metalwork, especially the exquisite pieces found in the tombs of Sipán in the Lambayeque valley. Working in gold and silver, Moche artists were adept at hammering, soldering, and setting stones, as well as developing a process to make a copper-gold alloy appear to be solid gold—a technique known as depletion gilding. Gold, silver, semiprecious stones and Spondylus shell were used to make the elaborate regalia of the highest elites. Massive necklaces and bracelets, ear spools, headdresses, nose ornaments, and more were made by Moche artists for the great lords. While there certainly were skilled ceramicists in the north and able metalsmiths in the south, the general division of materials between these two areas helps define some of their differences. Both areas also would have had weavers producing fine textiles, but few examples have survived.

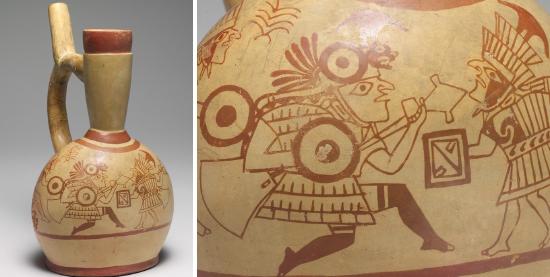

Iconography, Ideology, and Human Sacrifice

Early scholars assumed that armed conquest was the mechanism of power for the Moche state and Moche art certainly has a great deal of imagery relating to armed combat. However, it now appears that only some Moche expansion was due to military action. Other areas seem to have simply been colonized in uninhabited areas, or Moche culture was adopted by local elites who were impressed by the ideology. The imagery of combat is, in large part, related to that ideology, but not as a call to conquest. Instead, it seems that a lot of Moche combat imagery has ritual meaning. It focuses on hand-to-hand combat between two individuals, using cone-headed clubs as weapons and small shields for defense. Interestingly, this ignores what we know archaeologically about Moche warfare—which included the use of spears and darts propelled by throwing sticks, as well as slings used to propel stones with astonishing force. The Moche artwork, in other words, tells us one thing about their culture but omits other things. We can think of this as a form of propaganda—emphasizing the ritual aspects of Moche elite power rather than the more practical aspects of war. Moche art and archaeology also tell us what the point of this hand-to-hand combat was.

In the art, we see victorious warriors knocking the helmet off of their foe, sometimes bloodying their nose in the process. The defeated warrior is then stripped of his armor and clothing. With a rope tied around his neck, he is led by the victor, who carries the armor and clothing in a bundle to signify his victory. The defeated warriors are eventually sacrificed in an elaborate ritual, their necks sliced and blood collected, to be drunk by figures that are dressed in the costumes of gods.

Archaeologists have uncovered three sets of sacrificed prisoners at the site of Huaca de la Luna in the Moche river valley. These large-scale sacrifices took place at different times over the course of hundreds of years. The skeletons show signs of having undergone combat, as well as having had their throats slit. These remains seem to show that what is depicted in the art was also carried out in life (at least these three times). Whether smaller-scale sacrifices related to this imagery took place is still being investigated, at Huaca de la Luna and other large Moche sites. The continued archaeological exploration and analysis of Moche artworks will help researchers to further understand this complex culture.

Moche vessels, with a distinctive stirrup spout that evokes much older ceramics from the Chavin and Cupisnique cultures, were produced in large numbers by first shaping the clay in a mold and then finishing the pieces by hand. In this video, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Sarah Scher discuss this vessel in the shape of a portrait head, and what the distinctive markings under the chin tell us about this piece and Moche culture.

Figure \(\PageIndex{47}\): Portrait Head Bottle, Moche culture, Peru, 5th–6th century. Ceramic, 32.39 cm high. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain)

- Dr. Sarahh Scher, "Introduction to Andean Cultures," in Smarthistory, October 6, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Jayne Yantz, "Nasca Geoglyphs ," in Smarthistory, October 1, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Lois Martin, "The Paracas Textile," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Sarahh Scher, "Moche culture, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 27, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)