2.12: High Renaissance

- Page ID

- 143499

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The High Renaissance was centered in Rome, and lasted from about 1490 to 1527, with the end of the period marked by the Sack of Rome. Stylistically, painters during this period were influenced by classical art, and their works were harmonious. The restrained beauty of a High Renaissance painting is created when all of the parts and details of the work support the cohesive whole. While earlier Renaissance artists would stress the perspective of a work, or the technical aspects of a painting, High Renaissance artists were willing to sacrifice technical principles in order to create a more beautiful, harmonious whole. The factors that contributed to the development of High Renaissance painting were twofold. Traditionally, Italian artists had painted in tempera paint. During the High Renaissance, artists began to use oil paints, which are easier to manipulate and allow the artist to create softer forms. Additionally, the number and diversity of patrons increased, which allowed for greater development in art.

The High Renaissance represents the culmination of the goals of the Early Renaissance, namely the realistic representation of figures in space rendered with credible motion and in an appropriately decorous style. The most well known artists from this phase are Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and Michelangelo. Their paintings and frescoes are among the most widely known works of art in the world. Da Vinci’s Last Supper, Raphael’s The School of Athens and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling paintings are the masterpieces of this period and embody the elements of the High Renaissance.

Painting in the High Renaissance

The 16th century (1500’s) is considered to be the high point in the development of Renaissance art. We look mainly at three figures from this period: Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. This is the moment when artists begin to be recognized for their skill and sought after accordingly. The term “genius” is used for these figures. Giorgio Vasari, in possibly the first art history text, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, allies the talents of artists like Michelangelo with the Divine – literally, touched by God.

Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo was the oldest of the three. Born in the Tuscan town of Vinci – Italian artists are often called after their place of origin – he was apprenticed at 14 to the Florentine artist Verrochio. This was one of the most successful studiolos in Florence with the Medicis as patrons among others. Perugino and Botticelli were also associated with Verrocchio’s studio.2 Leonardo painted very few actual paintings in his lifetime. He made money inventing weapons, waterworks and other things for wealthy condotierri and others as his many notebooks attest. His paintings were, however, of such a unique quality that they are revered today.

His Madonna of the Rocks, from 1491 – 99, and 1506 – 08, shows his skill with glazes of oil paint and manipulation of light to create the sfumato, or smoky softness, of the edges of things.

The Madonna and Child with St. Anne uses the compositional device of the triangle to arrange the figures of a grown woman on another’s lap in a typically Renaissance rational, geometric arrangement.

The Last Supper

Da Vinci’s most celebrated painting of the 1490s is The Last Supper, which was painted for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan. The painting depicts the last meal shared by Jesus and the 12 Apostles where he announces that one of them will betray him. When finished, the painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece of design. This work demonstrates something that da Vinci did very well: taking a very traditional subject matter, such as the Last Supper, and completely re-inventing it.

Prior to this moment in art history, every representation of the Last Supper followed the same visual tradition: Jesus and the Apostles seated at a table. Judas is placed on the opposite side of the table of everyone else and is effortlessly identified by the viewer. When da Vinci painted The Last Supper he placed Judas on the same side of the table as Christ and the Apostles, who are shown reacting to Jesus as he announces that one of them will betray him. They are depicted as alarmed, upset, and trying to determine who will commit the act. The viewer also has to determine which figure is Judas, who will betray Christ. By depicting the scene in this manner, da Vinci has infused psychology into the work.

Unfortunately, this masterpiece of the Renaissance began to deteriorate immediately after da Vinci finished painting, due largely to the painting technique that he had chosen. Instead of using the technique of fresco, da Vinci had used tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso in an attempt to bring the subtle effects of oil paint to fresco. His new technique was not successful, and resulted in a surface that was subject to mold and flaking.

Where do the orthogonals lead in the one-point linear perspective in this painting?

Mona Lisa

Among the works created by da Vinci in the 16th century is the small portrait known as the Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda, wife of Francesco del Giocondo who commissioned the painting (but never got it). In the present era it is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Its fame rests, in particular, on the elusive smile on the woman’s face—its mysterious quality brought about perhaps by the fact that the artist has subtly shadowed the corners of the mouth and eyes so that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined.

The shadowy quality for which the work is renowned came to be called sfumato, the application of subtle layers or “glazes” of translucent paint so that there is no visible transition between colors, tones, and often objects. Other characteristics found in this work are the unadorned dress, in which the eyes and hands have no competition from other details; the dramatic landscape background, in which the world seems to be in a state of flux; the subdued coloring; and the extremely smooth nature of the painterly technique, employing oils, but applied much like tempera and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable. And again, da Vinci is innovating upon a type of painting here. Portraits were very common in the Renaissance. However, portraits of women were always in profile, which was seen as proper and modest. Here, da Vinci present a portrait of a woman who not only faces the viewer but follows them with her eyes.

Sculpture in the High Renaissance

Sculpture in the High Renaissance demonstrates the influence of classical antiquity and ideal naturalism.

During the Renaissance, an artist was not just a painter, or an architect, or a sculptor. They were typically all three. As a result, we see the same prominent names producing sculpture and the great Renaissance paintings. Additionally, the themes and goals of High Renaissance sculpture are very much the same as High Renaissance painting. Sculptors during the High Renaissance were deliberately quoting classical precedents and they aimed for ideal naturalism in their works. Michelangelo (1475–1564) is the prime example of a sculptor during the Renaissance; his works best demonstrate the goals and ideals of the High Renaissance sculptor.

Michelangelo

Bacchus

The Bacchus is Michelangelo’s first recorded commission in Rome. The work is made of marble, it is life sized, and it is carved in the round. The sculpture is of the god of wine, who is holding a cup and appears drunk. The references to classical antiquity are clear in the subject matter, and the body of the god is based on the Apollo Belvedere, which Michelangelo would have seen while in Rome. Not only is the subject matter influenced by antiquity, but so are the artistic influences.

Pieta

While the Pieta is not based on classical antiquity in subject matter, the forms display the restrained beauty and ideal naturalism that was influenced by classical sculpture. Commissioned by a French Cardinal for his tomb in Old St. Peter’s, it is the work that made Michelangelo’s reputation. The subject matter of the Virgin cradling Christ after the crucifixion was uncommon in the Italian Renaissance, indicating that it was chosen by the patron.

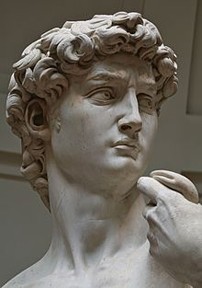

David

When the David was completed, it was intended to be sit on the roofline of the Florentine Cathedral. But Florentines during that time recognized it as so special and beautiful that they actually had a meeting about where to place the sculpture. Members of the group that met included the artists Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli. What about this work made it stand out so spectacularly to Michelangelo’s peers? The work demonstrates classical influence. The work is nude, in emulation of Greek and Roman sculptures, and the David stands in a contrapposto pose. He shows restrained beauty and ideal naturalism. Additionally, the work demonstrates an interest in psychology, which was new to the High Renaissance, as Michelangelo depicts David concentrating in the moments before he takes down the giant. The subject matter was also very special to Florence as David was traditionally a civic symbol. The work was ultimately placed in the Palazzo Vecchio and remains the prime example of High Renaissance sculpture.

David by Michelangelo, c.1504: This work by Michelangelo remains the prime example of High Renaissance sculpture. Detail CC BY-SA 3.0 Jorg Bittner Unna

Michelangelo believed sculpture to be the purest, highest form of art. Nevertheless, he is just as well-known for the fresco paintings he did for a number of popes. In 1508 Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Ceiling in the Vatican. He offered him the chance to do all the sculpture on his, Julius’, tomb in return. Reluctantly, Michelangelo agreed and created one of the most iconic set of images in the Western canon.

The program is drawn from the Old Testament, but as in much of Christian imagery it prefigures the New. Prophets and Sibyls line the ceiling foretelling the coming of the Christian Messiah. Stories, like that of Jonah and the Whale (dead for 3 days then alive again) prefigure the Resurrection. Down the center Michelangelo has created individual frames with the stories from Genesis – God creating Adam is possibly the best-known. Michelangelo creates heroic Classical male bodies that suggest the sculpture he would rather have been making. Dividing each frame and perched on plinths are male youths called “ignudi” whose purpose is not clear. For a basic introduction to the Sistine Ceiling from the Khan Academy see:

Raphael

Raphael Sanza was an Italian Renaissance painter and architect whose work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition.

Key Points

- Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael forms the traditional trinity of great masters of the High Renaissance. He was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop, and despite his death at 30, he had a large body of work.

- Some of Raphael’s most striking artistic influences come from the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci; because of this inspiration, Raphael gave his figures more dynamic and complex positions in his earlier compositions.

- Raphael’s “Stanze” masterpieces are very large and complex compositions that have been regarded among the supreme works of the High Renaissance. They give a highly idealized depiction of the forms represented, and the compositions, though very carefully conceived in drawings, achieve sprezzatura, the art of performing a task so gracefully it looks effortless.

Key Terms

- sprezzatura: The art of performing a difficult task so gracefully that it looks effortless.

- loggia: A roofed, open gallery.

- contrapposto: The position of a figure whose hips and legs are twisted away from the direction of the head and shoulders.

Overview

Raphael (1483–1520) was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period. He was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop; despite his death at 30, a large body of his work remains among the most famous of High Renaissance art.

Influences

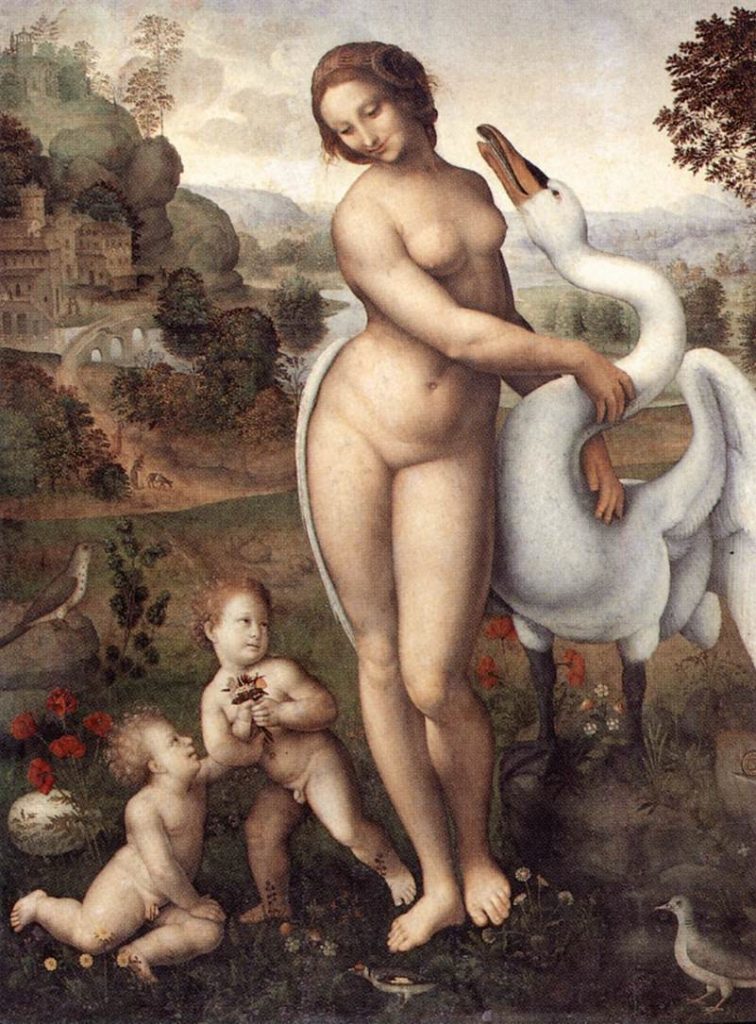

Some of Raphael’s most striking artistic influences come from the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. In response to da Vinci’s work, in some of Raphael’s earlier compositions he gave his figures more dynamic and complex positions. For example, Raphael’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1507) borrows from the contrapposto pose of da Vinci’s Leda and the Swans. Note the white wing of the swan as it folds around Leda’s body.

While Raphael was also aware of Michelangelo’s works, he deviates from his style. In his Deposition of Christ, Raphael draws on classical sarcophagi to spread the figures across the front of the picture space in a complex and not wholly successful arrangement.

The Stanze Rooms and the Loggia

In 1511, Raphael began work on the famous Stanze paintings, which made a stunning impact on Roman art, and are generally regarded as his greatest masterpieces. The Stanza della Segnatura contains The School of Athens, Poetry, Disputa, and Law. The School of Athens, depicting Plato and Aristotle, is one of his best known works. These very large and complex compositions have been regarded ever since as among the supreme works of the High Renaissance, and the “classic art” of the post-antique West. They give a highly idealized depiction of the forms represented, and the compositions—though very carefully conceived in drawings— achieve sprezzatura, a term invented by Raphael’s friend Castiglione, who defined it as “a certain nonchalance that conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless.”

View of the Stanze della Segnatura, frescoes painted by Raphael

In the later phase of Raphael’s career, he designed and painted the Loggia at the Vatican, a long thin gallery that was open to a courtyard on one side and decorated with Roman style grottos, or cave-like garden ornaments. He also produced a number of significant altarpieces, including The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna. His last work, on which he was working until his death, was a large Transfiguration which, together with Il Spasimo(Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary), shows the direction his art was taking in his final years, becoming more proto-Baroque than Mannerist.

The Master’s studio

Raphael ran a workshop of over 50 pupils and assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own right. This was arguably the largest workshop team assembled under any single old master painter, and much higher than the norm. They included established masters from other parts of Italy, probably working with their own teams as sub-contractors, as well as pupils and journeymen.

Draftsman

Raphael was one of the finest draftsmen in the history of Western art, and used drawings extensively to plan his compositions. According to a near-contemporary, when beginning to plan a composition, he would lay out a large number of his stock drawings on the floor, and begin to draw “rapidly,” borrowing figures from here and there. Over 40 sketches survive for the Disputa in the Stanze, and there may well have been many more originally (over 400 sheets survived altogether).

As evidenced in his sketches for the Madonna and Child, Raphael used different drawings to refine his poses and compositions, apparently to a greater extent than most other painters. Most of Raphael’s drawings are rather precise—even initial sketches with naked outline figures are carefully drawn, and later drawings often have a high degree of finish, with shading and sometimes highlights in white. They lack the freedom and energy of some of da Vinci’s and Michelangelo’s sketches, but are almost always very satisfying aesthetically.

Renaissance Architecture in Florence

Renaissance architecture first developed in Florence in the 15th century and represented a conscious revival of classical styles.

Key Points

- The Renaissance style of architecture emerged in Florence not as a slow evolution from preceding styles, but rather as a conscious development put into motion by architects seeking to revive the golden age of classical antiquity.

- The Renaissance style eschewed the complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of Gothic structures, and placed emphasis on symmetry, proportion, geometry, and regularity of parts.

- 15th century architecture in Florence featured the use of classical elements such as orderly arrangements of columns, pilasters, lintels, semicircular arches, and hemispherical domes.

- Filippo Brunelleschi was the first to develop a true Renaissance architecture.

- While the enormous brick dome that covers the central space of the Florence Cathedral used Gothic technology, it was the first dome erected since classical Rome and became a ubiquitous feature in Renaissance churches.

- The buildings of the early Renaissance in Florence expressed a new sense of light, clarity, and spaciousness that reflected the enlightenment and clarity of mind glorified by the philosophy of Humanism.

Key Terms

- quattrocento: Term that denotes the 1400s, which may also be referred to as the 15th century Renaissance Italian period.

- entablature: The part of a classical temple above the capitals of the columns; includes the architrave, frieze, and cornice but not the roof.

- pilaster: A rectangular column that projects partially from the wall to which it is attached; it gives the appearance of a support, but is only for decoration.

The Quattrocento, or the 15th century in Florence, was marked by the development of the Renaissance style of architecture, which represented a conscious revival and development of ancient Greek and Roman architectural elements. The rules of Renaissance architecture were first formulated and put into practice in 15th century Florence, whose buildings subsequently served as an inspiration to architects throughout Italy and Western Europe.

The Renaissance style of architecture emerged in Florence not as a slow evolution from preceding styles, but rather as a conscious development put into motion by architects seeking to revive a golden age. These architects were sponsored by wealthy patrons including the powerful Medici family and the Silk Guild, and approached their craft from an organized and scholarly perspective that coincided with a general revival of classical learning. The Renaissance style deliberately eschewed the complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of Gothic structures. Instead, Renaissance architects placed emphasis on symmetry, proportion, geometry, and regularity of parts as demonstrated in classical Roman architecture. They also made considerable use of classical antique features such as orderly arrangements of columns, pilasters, lintels, semicircular arches, and hemispherical domes.

The person generally credited with originating the Renaissance style of architecture is Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), whose first major commission—the enormous brick dome that covers the central space of the Florence Cathedral—was also perhaps architecturally the most significant. Known as the Duomo, the dome was engineered by Brunelleschi to cover a spanning in the already existing Cathedral. The dome retains the Gothic pointed arch and the Gothic ribs in its design. The dome is structurally influenced by the great domes of Ancient Rome such as the Pantheon, and it is often described as the first building of the Renaissance. The dome is made of red brick and was ingeniously constructed without supports, using a deep understanding of the laws of physics and mathematics. It remains the largest masonry dome in the world and was such an unprecedented success at its time that the dome became an indispensable element in church and even secular architecture thereafter. Khan Academy gives a good, brief overview of what it took for Brunelleschi to create the dome on the Florence Cathedral:

Another key figure in the development of Renaissance architecture in Florence was Leon Battista Alberti (1402—1472), an important Humanist theoretician and designer, whose book on architecture De re aedificatoria was the first architectural treatise of the Renaissance. Alberti designed two of Florence’s best known 15th century buildings: the Palazzo Rucellai and the facade of the church of Santa Maria Novella. The Palazzo Rucellai, a palatial townhouse built 1446–51, typified the newly developing features of Renaissance architecture, including a classical ordering of columns over three levels and the use of pilasters and entablatures in proportional relationship to each other.

The buildings of the early Renaissance in Florence expressed a new sense of light, clarity, and spaciousness that reflected the enlightenment and clarity of mind glorified by the philosophy of Humanism.

The Venetian Painters of the High Renaissance

Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese were the preeminent Venetian painters of the High Renaissance.

Key Points

- The Venetian High Renaissance artists Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese employed novel techniques of color, scale, and composition, which established them as acclaimed artists north of Rome.

- In particular, these three painters followed the Venetian School ‘s preference of color (colorito) over disegno.

- Giorgio Barbarelli da Castlefranco, known as Giorgione (c. 1477–1510), is an artist who had considerable impact on the Venetian High Renaissance. Giorgione was the first to paint with oil on canvas.

- Tiziano Vecelli, or Titian (1490–1576), was arguably the most important member of the Venetian school, as well as one of the most versatile. His use of color would have a profound influence not only on painters of the Italian Renaissance, but on future generations in Western art.

- Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) was one of the primary Renaissance painters in Venice, known for his paintings such as The Wedding at Cana and The Feast in the House ofLevi.

Key Terms

- disegno: Drawing or design, linear style.

- colorito: color and painterly brushwork.

- Venetian School: The distinctive, thriving, and influential art scene in Venice, Italy, starting from the late 15th century.

Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese were the preeminent painters of the Venetian High Renaissance. All three similarly employed novel techniques of color and composition, which established them as acclaimed artists north of Rome. In particular, Giorgione, Titian, and Veronese follows the Venetian School’s preference of color over disegno.

Giorgione

Giorgio Barbarelli da Castlefranco, known as Giorgione (c. 1477–1510), is an artist who had considerable impact on the Venetian High Renaissance. Unfortunately, art historians do not know much about Giorgione, partly because of his early death at around age 30, and partly because artists in Venice were not as individualistic as artists in Florence. While only six paintings are accredited to him, they demonstrate his importance in the history of art as well as his innovations in painting.

Giorgione was the first to paint with oil on canvas. Previously, people who used oils were painting on panel, not canvas. His works do not contain much under-drawing, demonstrating how he did not adhere to Florentine disegno, and his subject matters remain elusive and mysterious. One of his works that demonstrates all three of these elements is The Tempest (c. 1505–1510). This work is oil on canvas, x-rays show there is very little under drawing, and the subject matter remains one of the most debated issues in art history.

Titian

Tiziano Vecelli, or Titian (1490–1576), was arguably the most important member of the 16th century Venetian school, as well as one of the most versatile; he was equally adept with portraits, landscape backgrounds, and mythological and religious subjects. His painting methods, particularly in the application and use of color, would have a profound influence not only on painters of the Italian Renaissance, but on future generations of Western art. Over the course of his long life Titian’s artistic manner changed drastically, but he retained a lifelong interest in color. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid, luminous tints of his early pieces, their loose brushwork and subtlety of polychromatic modulations were without precedent.

In 1516, Titian completed his well-known masterpiece, the Assumption of the Virgin, or the Assunta, for the high altar of the church of the Frari. This extraordinary piece of colorism, executed on a grand scale rarely before seen in Italy, created a sensation. The pictorial structure of the Assumption—uniting in the same composition two or three scenes superimposed on different levels, earth and heaven, the temporal and the infinite.

Veronese

Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) was one of the primary Renaissance painters in Venice, well known for paintings such as The Wedding at Cana and The Feast in the House of Levi. Veronese is known as a supreme colorist, and for his illusionistic decorations in both fresco and oil. His most famous works are elaborate narrative cycles, executed in the dramatic and colorful style, full of majestic architectural settings and glittering pageantry.

His large paintings of biblical feasts executed for the refectories of monasteries in Venice and Verona are especially notable. For example, in The Wedding at Cana, which was painted in 1562–1563 in collaboration with Palladio, Veronese arranged the architecture to run mostly parallel to the picture plane, accentuating the processional character of the composition. The artist’s decorative genius was to recognize that dramatic perspective effects would have been tiresome in a living room or chapel, and that the narrative of the picture could best be absorbed as a colorful diversion.

The Feast in the House of Levi was originally meant as a Last Supper. The Counter- Reformation church found it not to display the proper decorum and called Veronese before the Inquisition. Rather than repaint his masterpiece, Veronese changed the name to a story that put Christ in the colorful company of ordinary people. Christ would say when questioned about why he would want to rub shoulders with such rabble that he wasn’t needed by the already converted. The Inquisition couldn’t argue with that.