2.11: Early Renaissance

- Page ID

- 143498

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Italian Renaissance

The art of the Italian Renaissance was a cultural shift from the styles of the Middle Ages and Byzantia; the concepts of the Renaissance remained influential throughout Europe and other parts of the world for centuries.

Key Points

- The Renaissance, or “rebirth” of learning, is thought to have begun in the mercantile city of Florence and the Florentine school of painting became the dominant style during the period. Renaissance artworks often depicted more secular subject matter, or pagan themes than previous artistic movements.

- Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Rafael are among the best known painters of the High Renaissance.

- The High Renaissance was followed by the Mannerist movement, known for elongated figures, irrational spaces, and complex iconography.

Key Terms

- Buonfresco: A type of wall painting in which color pigments are mixed with water and applied to wet plaster. As the plaster and pigments dry, they fuse together and the painting becomes a part of the wall itself.

- Fresco secco: as in buon fresco except the paint is applied to a dry wall and is usually not as long lasting and intense.

- Mannerism: A style of art developed at the end of the High Renaissance, characterized by the deliberate distortion and exaggeration of perspective, especially the elongation of figures.

The Renaissance began during the 15th century and remained the dominate style in Italy, and in much of Europe, until the end of the 16th century. The term “renaissance” was only developed during the 19th century in order to describe this period of time and its accompanying artistic style and to differentiate it from what had gone before – the so-called “Dark Ages.” However, people who were living during the Renaissance did, in fact, see themselves as different from their medieval predecessors. Through a variety of texts that survive, we know that people living during the Renaissance saw the earlier centuries as a time when much of the scholarship and artistic ability had been lost. For the Renaissance elite theirs would be a time when the brilliance of the Ancients in art and architecture would be recovered and built upon.

Florence and the Renaissance

When you picture an object from the Renaissance, you are probably picturing something done in the style that was developed in Florence and which became the dominate style of art during this period. Italy at this time was divided into a number of different city states. Each one had its own government, culture, economy, and artistic style. There were a number of subtle differences in art and architecture that arose in various parts of Italy during the Renaissance, and other geographical areas like Northern Europe also developed stylistic and content specialties. Siena, which was a political ally of France, for example, retained a Gothic element to its art for much of the Renaissance.

Certain conditions aided the development of the Renaissance style in Florence during this time period. In the 15th century, Florence became a major mercantile center. The production of cloth drove their economy and a wealthy and influential merchant class emerged. Humanism, which had developed during the 14th century, remained an important intellectual movement that impacted art production as well.

Early Renaissance

During the Early Renaissance, artists began to reject the Byzantine style of religious painting and strove to create realism in their depiction of the human form and space. This aim toward realism began with Cimabue and Giotto, and can be seen in its early Renaissance form in the art of artists such as Andrea Mantegna and Paolo Uccello. These artists created works that employed one point perspective and displayed their skill with perspective for their educated, art knowledgeable viewers.

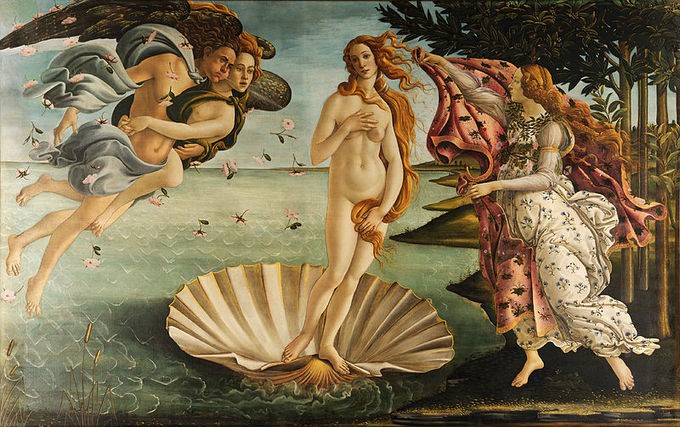

During the Early Renaissance we also see important developments in subject matter in addition to style. While religion continued to be an important element in the daily lives of people of the period and remained a driving factor behind artistic production, we also see a new avenue open to panting—“mythological” subject matter. Many scholars point to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus as the very first panel painting of a Classical scene. While the tradition itself likely arose from cassone (marriage chest) painting, which typically featured scenes from Greek and Roman stories and romantic texts, the development of panel painting with these subjects would open a creative new world for artistic patronage, production, and themes.

Humanism and the Early Renaissance

Humanism was an intellectual movement embraced by scholars, writers, and civic leaders in 14th century Italy.

Key Points

- Humanists reacted against the utilitarian approach to education, seeking to create a citizenry who were able to speak and write with eloquence and thus able to engage the civic life of their communities.

- The movement was largely founded on the ideals of Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca, which were often centered around humanity’s potential for achievement.

- While Humanism initially began as a predominantly literary movement, its influence quickly pervaded the general culture of the time, reintroducing classical Greek and Roman art forms and leading to the Renaissance.

- Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, known especially for his Humanist, and unusually erotic, statue of David.

- While medieval society viewed artists as anonymous servants and craftspeople, Renaissance artists were trained intellectuals whose names were known and valued, and their art reflected this newfound point of view.

- In humanist painting, the treatment of the elements of perspective and depiction of light became of particular concern.

Key Terms

- High Renaissance: The period in art history denoting the apogee of the visual arts in the Italian Renaissance. The High Renaissance period is traditionally thought to have begun in the 1490s—with Leonardo’s fresco of The Last Supper in Milan and the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence— and to have ended in 1527, with the Sack of Rome by the troops of Charles V.

Overview

Humanism, also known as Renaissance Humanism, was an intellectual movement embraced by scholars, writers, and civic leaders in 14th- and early-15th-century Italy. The movement developed in response to the medieval scholastic conventions in education at the time, which emphasized practical, pre-professional, and scientific studies engaged in solely for job preparation, and typically by men alone. Humanists reacted against this utilitarian approach, seeking to create a citizenry who were able to speak and write with eloquence and thus able to engage the civic life of their communities. This was to be accomplished through the study of the “studiahumanitatis,” known today as the humanities: grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. Humanism introduced a program to revive the cultural—and particularly the literary—legacy and moral philosophy of classical antiquity. The movement was largely founded on the ideals of Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca, which were often centered on humanity’s potential for achievement.

Humanists considered the ancient world to be the pinnacle of human achievement, and thought its accomplishments should serve as the model for contemporary Europe. There were important centers of Humanism in Florence, Naples, Rome, Venice, Genoa, Mantua, Ferrara, and Urbino.

Humanism was an optimistic philosophy that saw man as a rational and sentient being, with the ability to decide and think for himself. It saw man as inherently good by nature, which was in tension with the Christian view of man as the original sinner needing redemption. It provoked fresh insight into the nature of reality, questioning beyond God and spirituality, and provided knowledge about human history beyond that which was provided in Christian doctrine.

Humanist Art

Renaissance Humanists saw no conflict between their study of the Ancients and Christianity. The lack of perceived conflict allowed Early Renaissance artists to combine classical forms, classical themes, and Christian theology freely. Early Renaissance sculpture is a great vehicle to explore the emerging Renaissance style. The leading artists of this medium were Donatello, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Lorenzo Ghiberti. Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, known especially for his classical, and unusually erotic, statue of David, which became one of the icons of the Florentine republic.

Humanism affected the artistic community and how artists were perceived. Patronage of the arts became an important activity, and commissions included secular subject matter as well as religious. Important patrons, such as Cosimo de’ Medici, emerged and contributed largely to the expanding artistic production of the time.

In painting, the treatment of the elements of perspective and light became of particular concern. Paolo Uccello, for example, who is best known for “The Battle of San Romano,” was obsessed by his interest in perspective and would stay up all night in his study trying to grasp the exact vanishing point. He used perspective in order to create a feeling of depth in his paintings. In addition, the use of oil paint had its beginnings in the early part of the 16th century, and its use continued to be explored extensively throughout the High Renaissance.

Origins

Some of the first Humanists were great collectors of antique manuscripts, including Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Coluccio Salutati, and Poggio Bracciolini. Of the three, Petrarch was dubbed the “Father of Humanism” because of his devotion to Greek and Roman scrolls. Many worked for the organized church and were in holy orders (like Petrarch), while others were lawyers and chancellors of Italian cities (such as Petrarch’s disciple Salutati, the Chancellor of Florence) and thus had access to book-copying workshops.

In Italy, the Humanist educational program won rapid acceptance and, by the mid- 15th century, many of the upper classes had received Humanist educations, possibly in addition to traditional scholastic ones. Some of the highest officials of the church were Humanists with the resources to amass important libraries. Such was Cardinal Basilios Bessarion, a convert to the Latin church from Greek Orthodoxy, who was considered for the papacy and was one of the most learned scholars of his time.

Following the Crusader sacking of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, the migration of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés, who had greater familiarity with ancient languages and works, furthered the revival of Greek and Roman literature and science.

Early Renaissance Sculpture in Florence

Renaissance sculpture originated in Florence in the 15th century and was deeply influenced by classical sculpture.

Key Points

- Renaissance sculpture proper is often thought to have begun with the famous competition for the doors of the Florence baptistery in 1403, which was won by Lorenzo Ghiberti.

- Ghiberti designed a set of doors for the competition, housed in the northern entrance, and another more splendid pair for the eastern entrance, named the Gates of Paradise. Both of these gates depict biblical scenes.

- Ghiberti set up a large workshop in which many famous Florentine sculptors and artists were trained. He revived the lost wax casting of bronze, a technique that had been used by the ancients and had subsequently been lost.

- Donatello created his bronze David for Cosimo de’ Medici. Conceived independently of any architectural surroundings, it was the first known free- standing nude statue produced since antiquity.

- The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by wealthy patrons for their homes. Public sculpture became a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centers. Additionally, portrait sculpture, particularly busts, became hugely popular in Florence.

Key Terms

- allegory: The representation of abstract principles by characters or figures.

- lost wax: A method of casting a sculpture in which a model of the sculpture is made from wax: the model is used to make a mold; when the mold has set, the wax is made to melt and is poured away, leaving the mold ready to be used to cast the sculpture.

- baptistery: A designated space that may stand within a church as a separate room or even as a separate building associated with a church, where a baptismal font is located, and consequently, where the sacrament of Christian baptism is performed. Typically during the Renaissance, baptisteries were separate buildings as people would be baptized before entering a church or Cathedral.

Commonly known as “the cradle of the Renaissance,” 15th century Florence was among the largest and richest cities in Europe and its wealthiest residents were enthusiastic patrons of the arts, including sculpture. Departing from the International Gothic style that had previously dominated in Italy, and drawing from the styles of classical antiquity, Renaissance sculpture originated in Florence and consciously followed the models of the ancients.

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Renaissance sculpture proper is often thought to begin with the famous competition for the doors of the Florence baptistery in 1403, from which the trial models submitted by the winner, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and the runner up, Filippo Brunelleschi, still survive. Ghiberti’s bronze doors consist of 28 panels depicting scenes from the life of Christ, the four evangelists, and the Church Fathers Saints Ambrose, Jeromy, Gregory, and Augustine. They took 21 years to complete and still stand at the northern entrance of the baptistery, although they are eclipsed by the splendor of his second pair of gates for the eastern entrance, which Michelangelo dubbed “the Gates of Paradise.” These new doors were commissioned in 1425 and built over a 27-year period. They consist of 10 rectangular panels depicting scenes from the Old Testament and employ a clever use of the recently discovered principles of perspective to add depth to the composition. The “Gates of Paradise” are surrounded by a richly decorated gilt framework of fruit and foliage, statuettes of prophets, and busts of the sculptor and his father.

In order to carry out these huge commissions, Ghiberti set up a large workshop in which many famous Florentine sculptors and artists trained in later years, including Donatello, Michelozzo, and Paolo Uccello. He revived the lost wax casting of bronze, a technique which had been used by the ancients and subsequently lost. This made his workshop particularly famous and was a great draw for aspiring artists.

Donatello

Another deeply influential sculptor from Florence was Donatello (1386—1466), who is best known for his work in bas-relief, low or shallow relief, that he used as a medium for the incorporation of significant 15th century sculptural developments in perspectival illusion. Donatello received his early artistic training in a goldsmith’s workshop and then trained briefly in Ghiberti’s studio before undertaking a trip to Rome with Filippo Brunelleschi where he undertook the study and excavation of Roman architecture and sculpture. Roman art became the single most important influence on Donatello’s work. His foremost sponsor in Florence was Cosimo de’Medici, the city’s greatest patron of art.

Donatello created his bronze David for Cosimo’s court in the Palazzo Medici. Conceived entirely in the round and independent of any architectural surroundings, it was the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity and suggested an allegory of civic virtues overcoming brutality and ignorance. This sculpture represented a particularly important development in Renaissance sculpture: the production of sculpture independent of architecture, unlike the preceding International Gothic style where sculpture rarely existed except as decoration on a building.

Donatello stresses the youth of David by showing the unformed musculature of the arms and body. He still wears his shepherd’s hat and boots and holds Goliath’s sword in his hand and armor beneath his feet. A feather from the giant’s helm reaches suggestively up the inside of David’s leg (detail). Academic Michael Rocke has written that this may have been an allusion to the acceptance of physical relationships between older Florentine men and younger boys.1 It may then be another way of signaling David’s youth.

Donatello’s other important projects in and near Florence include the marble pulpit of the facade of the Prato cathedral, the carved Cantoria or choir at the Florence Duomo, which was influenced by ancient sarcophagi and Byzantine ivory chests, the Annunciation scene for the Cavalcanti altar in the church of Santa Croce, and a bust of Young Man with a Cameo, the first example of a lay bust portrait since the classical era.

Patronage of Sculpture

The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by wealthy patrons for their homes. Public sculpture became a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centers, and portrait sculpture, particularly busts, were hugely popular in Florence following Donatello’s innovations. These 15th century advances soon spread throughout Italy and later through the rest of Europe.

Early Renaissance Painting

Renaissance painting was developed in 15th century Florence when artists began to reject the flatness of Gothic painting and strive toward greater naturalism.

Key Points

- Florentine painting received a new lease on life in the early 15th century, when the use of linear perspective was formalized by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi and adopted by painters as an artistic technique.

- Other important techniques developed in Florence during the first half of the 15th century include the use of realistic proportions, foreshortening, sfumato, andchiaroscuro.

- The artist most widely credited with first popularizing these techniques in 15th century Florence is Masaccio (1401–1428), the first great painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaissance.

- Masaccio was deeply influenced both by Giotto’s earlier innovations in solidity of form and naturalism and Brunelleschi’s formalized use of perspective in architecture and sculpture, and moved away from the International Gothic style to a more realistic mode.

- Masaccio is best known for his frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, in which he employed techniques of linear perspective, such as the vanishing point for the first time, and had a profound influence on other artists despite the brevity of his career.

Key Terms

- vanishing point: The point in a perspective drawing at which parallel lines receding from an observer seem to converge.

- quattrocento: Renaissance Italian period during the 1400s.

- sfumato: “smoky” – the blurring of sharp outlines by subtle and gradual blending to give the illusion of three-dimensionality.

- chiaroscuro: the contrast between light and dark to convey a sense of depth or volume in a two-dimensional form.

- foreshortening: the artistic effect of shortening or compressing the view of an object that is at an angle to the picture plan to make it look as if it recedes away from the viewer.

Fifteenth century Florence was the birthplace of Renaissance painting, which rejected the flatness and stylized nature of Gothic art in order to focus on naturalistic representations of the human body and landscapes. While Giotto is often referred to as the herald of the Renaissance, there was a break in artistic developments in Italy after his death, due largely to the Black Death. However, Florentine painting was revitalized the early 15th century, when the use of perspective was formalized by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi and adopted by painters as an artistic technique. The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts.

Many other important techniques commonly associated with Renaissance painting developed in Florence during the first half of the 15th century, including the use of realistic proportions, foreshortening, sfumato, and chiaroscuro.

The artist most widely credited with first pioneering these techniques in 15th century Florence is Masaccio (1401–1428), the first great painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaissance. Born Tommaso di Ser Viovanni di Mone Cassai, his nickname Masaccio is a shortened version of Tommaso, and suggests “clumsy” or “messy” Tom. Masaccio was deeply influenced by both Giotto’s earlier innovations in solidity of form and naturalism and Brunelleschi’s formalized use of perspective in architecture and sculpture. Masaccio is best known for his frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, in which he employed techniques of linear perspective such as the vanishing point for the first time, and had a profound influence on other artists despite the brevity of his career.

Masaccio was friends with Brunelleschi and the sculptor Donatello, and collaborated frequently with the older and already renowned artist Masolino da Panicale (1383/4–1436) who traveled with him to Rome in 1423. From this point onwards, he eschewed the Byzantine and Gothic styles altogether, adopting traces of influence from ancient Greek and Roman art instead. These are evident in the cycle of frescoes he executed alongside Masolino for the Brancacci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The two artists started working on the chapel in 1425, but their work was completed by Filippo Lippi in the 1480s.

The frescoes in their entirety represent the story of human sin and redemption from the fall of Adam and Eve to the works of St. Peter. Giotto’s influence is evident in Masaccio’s frescoes, particularly in the weight and solidity of his figures and the vividness of their expressions. Unlike Giotto, Masaccio utilized linear and atmospheric perspective, and made even greater use of directional light and the chiaroscuro technique, enabling him to create even more convincingly lifelike paintings than his predecessor. His style and techniques became profoundly influential after his death and were imitated by his successors.

The Tribute Money is an example of “continuous narrative” in which the entire story that transpires over time is shown in episodes in the same image.

The tax collector (in contemporary 15th c. Italian costume) confronts Jesus and the Disciples for the taxes on the temple which is seen on the right in the background. The Disciples are agitated because no one has any money, but Jesus turns to Peter and tells him to go to the water and catch a fish. On the left we see Peter in his blue tunic with his orange over-garment cast aside catching the fish inside of which will be the coins for the tax collector. On the far right we see Peter paying said collector.

In this continuous narrative (the entire story is told in one image) Masaccio shows his mastery of the new art of perspective in the temple architecture – follow the orthogonals and see where they all meet. On the left he uses some atmospheric perspective in the blue/gray color of the mountains and suggests depth of field with the diminishing size of the trees along the shore.

One other innovation – at least from most medieval imagery – can be seen in the shadows of the figures which suggest gravity and anchor them to the earth. All of these devices would have appeared new and astoundingly realistic to a viewer of 1425. The idea of the Renaissance “window on the world” that is thrown wide and give you a real encounter with the most significant figures in your religion suggests the power of this new visual movement.

In his buon fresco Trinity, Masaccio shows a Classical barrel-vaulted space with a coffered ceiling viewed through a Roman arch with Corinthian capitals. There we see the Holy Trinity – God, the Holy Spirit (the white dove under God’s face), and Jesus with the Virgin and St. John on either side. Outside the sacred space are two more figures – the donors who have not been identified by art historians. The fresco continues below the level of the donors with a grisaille painting of a sarcophagus on the lid of which is a skeleton and an inscription that reads “As you are I once was; as I am so shall ye be.” This vanitas figure reminds viewers of the purpose of the image they see above them. Masaccio’s use of linear perspective in the coffered ceiling tells us that we are situated at about eye-level with the base the donors kneel on. This creation of a space that seemingly extends beyond our own and into which we could step if we could read it was a popular and influential composition for Renaissance fresco painting.