6.3: Contemporary African Art

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174447

Introduction

Africa is the second-largest of the continents; only Asia is larger. The continent is also the second-largest in population, with 1.341 billion people in 2020. Africa is diverse with 54 independent countries, three still dependent regions, and some disputed territory. The entire continent also has a very high linguistic range with an estimated 1500 to 2000 different African languages. The European colonial powers established the current borders of each country without any consideration for the ethnic, language, or religious groupings of the people. Still today, within the boundaries of some of the nations, conflicts erupt based on ethnic or religious differences. For centuries, only a few of the very northern parts of Africa were part of the Arab trade routes. In the fifteenth century, European countries established trading ports along the coasts of Africa.

The competition for the rich resources in the continent grew, and eventually, most of Africa was under the control of European nations. The Europeans took the natural resources and lands of the people, especially under the brutal regimes of colonization. Although the European countries withdrew from the region, they still maintain financial control over the lands in the form of foreign investments by Western companies, moving the profits outside the African countries. This led to massive poverty in Africa, and nearly one in three Africans were still in extreme poverty.[1] Director of the Africa Centre Kenneth Tharp said, "The legacy of aid means the world has been fed a diet of Africa as war-torn, poverty-stricken, without reflecting the incredible diversity of those 54 nations," he says. "Nigeria (where his father was born) is five times the size of UK with hundreds of languages spoken. We need to start to reflect the richness of that diversity. We need to get beyond the one story and start looking at the many stories."[2]The history of art in Africa is ancient and travels back through time, found in individuals, tribes, kingdoms, a long continuity based on social, economic, or governmental institutions.

Today, contemporary art in Africa cannot be categorized into a singular definition; the art is as diversified as the continent's countries, defined by its contextual parameters. Each of the artists comes from different backgrounds, and the historical events and cultures of their ancestors and families influence their creativity and art. Western artistic disciplines were brought to Africa during colonialism, and representational art was reinforced and replaced traditional African expressions. In the early twentieth century, the dynamics of Western art changed with the advent of Impressionism, Surrealism, or Cubism, all altering the concepts of color, shape, and form. African artists also became liberated from forced traditional European methods giving birth to new changes and pursuits for modern African artists.

By the 1980s, most African countries were freed of colonial rule and established their separate governments, and integrated into the global community. With travel, enhanced communications, and the media, African artists experience worldwide concepts while embracing their own cultures and traditions, making strong statements about the influence of globalization. They have also created a new unique art form as "nowhere else on the planet has become so inventive in creating sculptures, installations, and craft made from recycled found objects." Across the massive continent of Africa, artist identity grows from within their past ethnicities welded to contemporary ideas.

Willie Bester

Willie Bester (1956-) was born in Western Cape (8.3.1), South Africa, where he was classified as Coloured under South Africa's repressive apartheid system. His mother was Coloured (neither white nor native), and his father was a Xhosa (native Black African). The apartheid laws were based on a person's appearance or public perception and multiple other rules instituted by the government. The laws defined where a person could live, who they could marry, and how their children were classified. Bester's family was considered a mixed-race marriage, and they could not live together in segregated housing. They often lived separately or in backyards, the one home they had bulldozed, and their few possessions were taken. As a child, Bester was subjected to continuous harassment of his parents by the police. He created art from materials he found until a teacher encouraged him to paint. As a teen, he was compelled to join the Defense Force.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

By the 1980s, he joined the Community Arts Project, an organization supporting the anti-apartheid system. Before it was fashionable, Bester used the mixed media materials he found to create assembled images representing people's experiences under severe racist structures of apartheid. He used specific materials to communicate his artistic ideas combined with his political conscience. As negotiations to end apartheid began in 1990, Bester also used oil paint to depict portrait-like images of Black and Coloured people to celebrate the spirit of the people. When Mandela was elected president in 1994, Bester continued to work for human rights. He often combined found materials with oil paintings; the painted section created the story, and the multi-media objects supported the social and political concepts. Bester said, "I was brainwashed all my life to believe that I am worth less than other people. But art is strong, it states that you are also here, you are also somebody, and you are as good as anybody else. Art can restore your pride."[3]

One of Bester's recurring themes was supported by using the concept of children's shoes. He wanted to expose society's exploitation of missing and abused children and the realities of their lives. The Missing Ones (8.3.2) is made of steel and mounted on a metal frame. Each pair of shoes represents a missing child, young children, based on the size of the shoes. The shoes are scoffed and well-worn, usually the only pair a child owned. Tags hang on some of the shoes; the only identity left for the owners of the shoes; the disposition of the child lost to history.

1913 Land Act (8.3.3) was based on the government's South African Land Act law passed in 1913. The law took most of the land from the millions of black inhabitants, and it was deeded to the white people. At the top of the bench, the curving branch is inscribed with Europeans Only. A snake representing the evil of the apartheid system is curled around the branch. The painting on the bench depicts the people forced from their land by the law. The bulldozer is demolishing the people's houses. A mother is feeding her baby as a large hand holds bullets in her face. The chain encircles the bench, fencing and enclosing the people into segregated compounds. Bester's work made people feel uncomfortable; however, he wanted to relay the truths of injustice.

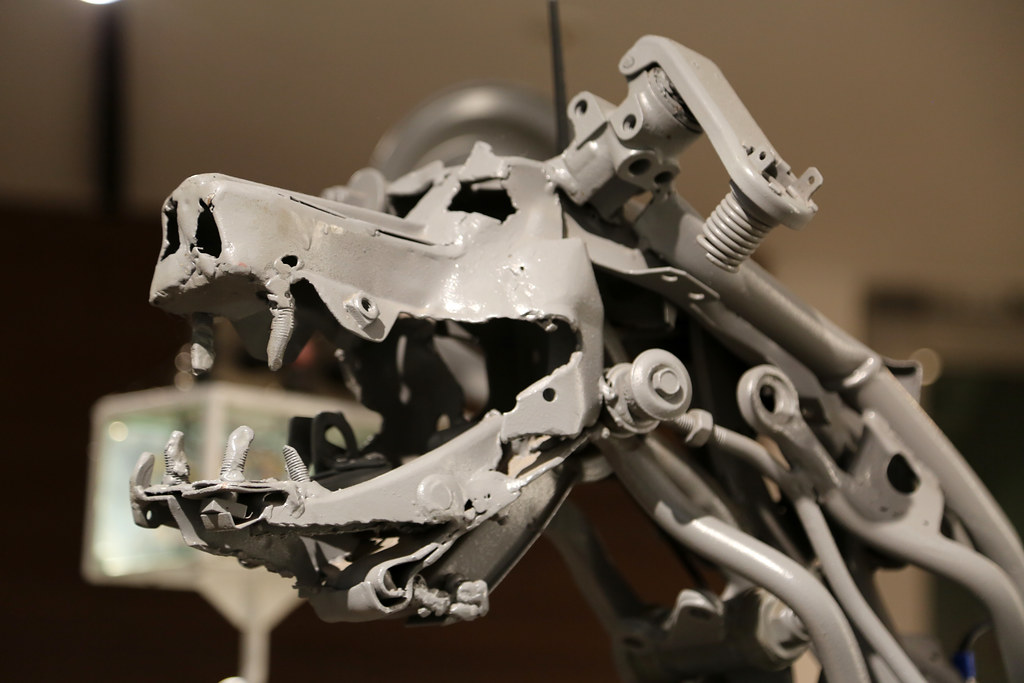

Dogs of War (8.3.4) depicts the menacing look of a fierce dog released from its controller. The dog moves forward, growling and snarling, its mouth open, ready for attack. The sculpture was made with welded metal parts from different machines, a machine gun on its back, and a rocket attached to its front legs, adding to the lethal and dangerous look. The image of the dog was part of the control by the apartheid government and a form of police brutality. The police and their German shepherds became symbolic and the focus of multiple artists, anthropomorphizing the dogs with human features and police caps. Bester took the dogs further into a futuristic robotic dog, able to exert control by itself. Bester's dog became representative of the earlier controls, unseen yet still present. Some critics were upset because Bester still rips the cover off the past in his relentless pursuit of justice. He grew up under apartheid and did not forget its dreadful past and the ramifications of the period.

Edson Chagas

Edson Chagas (1977-) was born in Angola (8.3.6) and studied photojournalism at the London College of Communication and the University of Newport in Wales and two schools in Portugal. He worked as an editor for a newspaper in Angola while creating his work and focused on consumerism in Angola. Originally, everything in the city of Luanda was reused; however, Chagas saw the change in consumer habits and the effects on the environment. His original set of photographs documented the changes to a disposable culture, abandoned objects, and the interaction with the environment. His photos of the broken chair against the side of a building or a pile of torn, dirty newspapers became sculptural symbols of the cities. After Angola's civil war ended in 2002, its financial position quickly grew, becoming one of Africa's fastest-growing economies.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

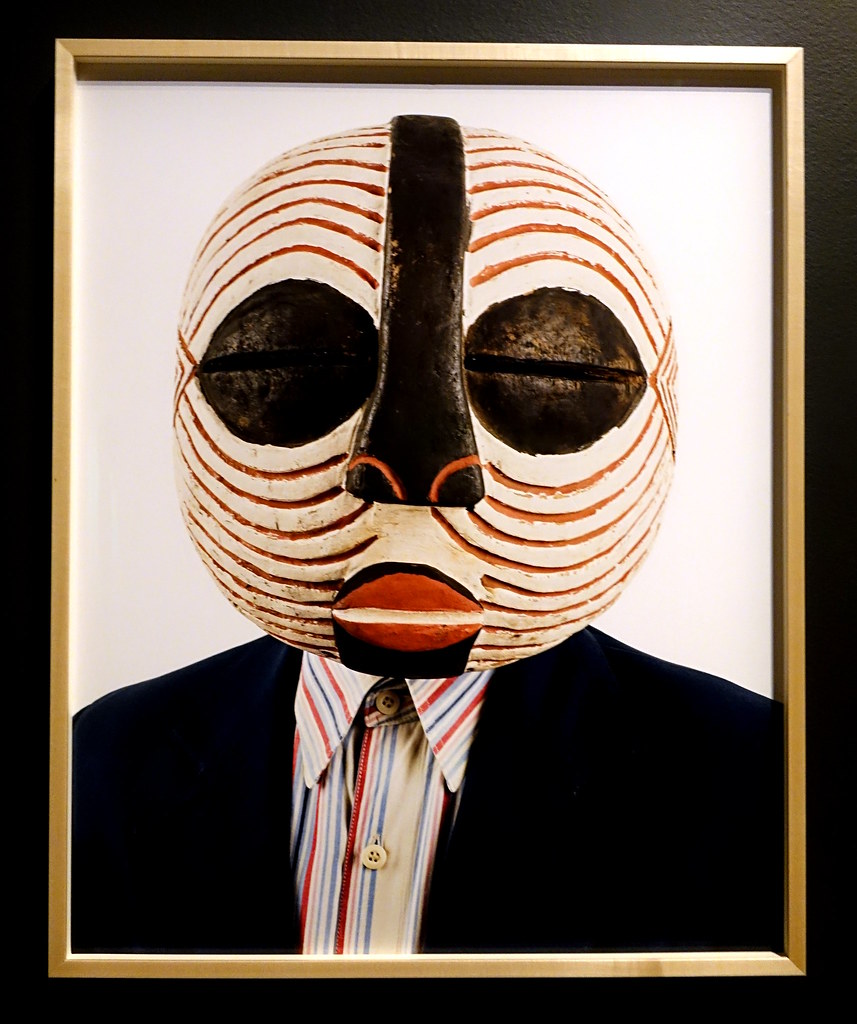

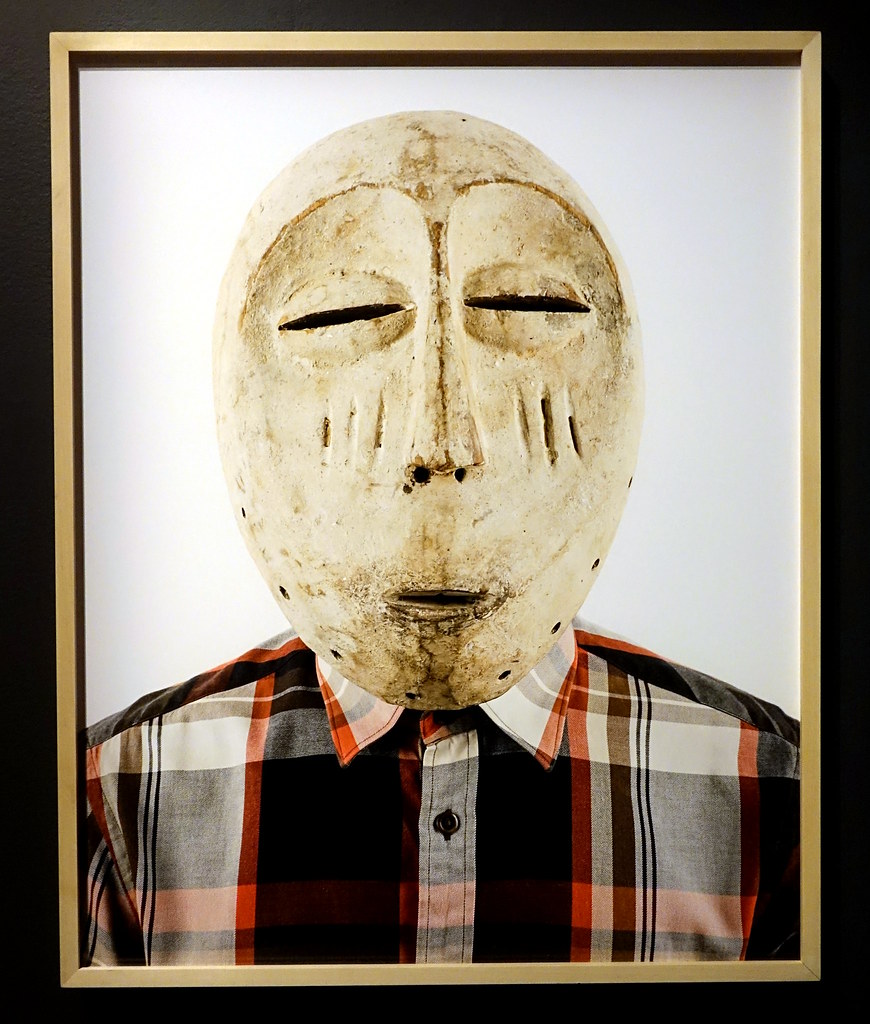

Chagas series Tino Passe focused on the concepts of consumerism in the cities. Originally, Angola was under Portuguese colonial rule from 1575 to 1975 when Angola became independent. During the time, the culture and traditions of the local populations were ignored, dismissed as primitive by the European colonialists. Masks were made initially for specific rituals and worn by influential people. Chagas used masks from collections now held in private or museums. He stripped any additional decorations, removed the masks' original meanings, then used the masks to hide the identity and characteristics of the person in the image. The definitions of the masks and people transformed into another context.

The people are dressed in contemporary attire from street markets or retailers who import clothing. Emmanuel C. Bofala's (8.3.7) basic facial features are hidden, now identified as someone with his eyes impassive, the lips closed and set without emotion. He wears conflicting stirpes in modern colors running vertically against the horizontal lines of the mask.

Fernando L. Makélélé (8.3.8) wears a plain white mask to contrast with the black, white, and red plaid shirt. The ceremonial face of the mask had meaning in its original use, and the image displays no meaning. Both people hid behind the masks originally designed with significant purposes in rituals and artistic in design and creation. The consumerism of cheaply reproduced clothing contrasts with the masks. In each image, the mask and clothing are complimentary. The people all might appear to be equal in importance, however, does the type of clothing change the meaning based on a westernized cultural belief of power. Is the man in a suit jacket more powerful or wealthier than the man in the simple plaid shirt?

Romuald Hazoumé

Romuald Hazoumé (1962-) was born in the Republic of Benin (8.3.9), part of the Yoruba people, a Sub-Saharan ethnic group of about forty-two million people. The Yoruba reside in different regions of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, and speak their own language. The Yoruba were documented in the early 1600s. However, oral and archaeological findings indicate they lived in the region in the early eleventh century. The Yoruba were urban dwellers long before the British colonial came with city-state structures built around the home of the powerful Oba. Archaeological features included terracotta, stone, brass, copper, and bronze used by artists. The Republic of Benin was known as the Kingdom of Dahomey from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries and called the slave coast. Large numbers of people were kidnapped from other areas and trafficked during the slave trade with European slave traders. When slavery ended, France governed the country from 1892 to 1960, when the people gained independence. Since then, the country has had a varied history with different governments and military coups. Today the country has a constitution and an elected president.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Hazoumé is known for using discarded and used materials for his artwork. Industrialized nations pay many African countries to dump their trash and garbage, including nuclear waste. Hazoumé uses some waste material to create his artwork sold back to European galleries. Some of the materials he incorporated were plastic containers smugglers used to bring petrol into Benin from neighboring countries. Hazoumé's work might be humorous or lighthearted with an overtone of political issues. He creates with a diverse set of materials and methods, including video, paint, photography, sculptures, and installation. The plastic petrol can was one of his primary materials and was seen in his installation Dream (8.3.10). For the boat in his photographic mural, Hazoumé positioned the containers with the opening's outward, gaping like a mouth, a voice against the dumping of Euro-American discards. The boat is 13.7 meters long, the black plastic containers assembled, and Dream was written on the side. On the floor is the inscription, "Damned if they leave and damned if they stay: better, at least, to have gone, and be damned in the boat of their dreams."[4] Hazoumé talked about the ingenuity of those with little economic support and the lack of ability to escape their condition.

Hazoumé wanted to understand the masks his Yoruba ancestors made and why they created them. He immersed himself in research, traveling throughout the region before returning to complete his versions. In Benin, every street was strewn with jerrycans, the plastic containers for petrol, the rubble of capitalism. Hazoumé used the containers for his masks. Twins (8.3.11) is one of his many masks made from plastic petrol cans. He uses the opening of the can for the mouth in most of his masks, the figure protesting the disposable society. In this mask, Hazoumé used acrylic to paint the can and embellished the mask with raffia threaded around the outside.

Gonçalo Mabunda

Gonçalo Mabunda (1975-) was born in Mozambique (8.3.12) two years before the long-lasting civil wars. By the eleventh century, small towns were established by people who developed a distinctive Swahili culture. They were located on the trade routes of the Indian Ocean. In 1498, the Portuguese colonized the area and controlled the region for over four centuries. Mozambique became independent in 1975, and after only two years of independence, the country descended into civil war from 1977 until 1992, resulting in the loss of over one million people. In 1994, Mozambique finally had multiparty elections and was relatively stable under the elected president. Mabunda grew up in the middle of the continued wars, heavily influencing his artwork. A few groups in Mozambique were established to collect weapons of war from villages and individuals. The weapons were deactivated and given to artists for use in their artwork. Mabunda is an artist and anti-war activist who used multiple weapons styles in his art. He incorporated automatic rifles, pistols, rockets, and shell casings of all types to create his anthropomorphic figures. His primary focus was to make masks based on the traditional masks of ancestral people. He also made thrones or seating from the different weapons; the throne is a contemptuous symbol of power based on the use of weapons and challenging the irrationality of war.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Whenever Mabunda selected weapons, he wondered if it killed one of his relatives. He stated, "Portions of my family, my neighbors, they all died in the war…How many people were killed with these weapons? This might be the one that killed some of my relatives."[5] The work he makes is personal to him. O Throne of a World (8.3.13) is one of many thrones Mabunda made and represented a criticism of African governments who use armed violence to maintain power. He also believes the thrones represent different attributes of power and an extension of tribal symbols. In this throne, the automatic rifles stand out in the background with pistols on each side. Small bombs act as legs, the throne is completed with different parts of weapons. Mabunda creates the artwork believing the power of art is transformative and supports the durability and creativity of African countries and societies.

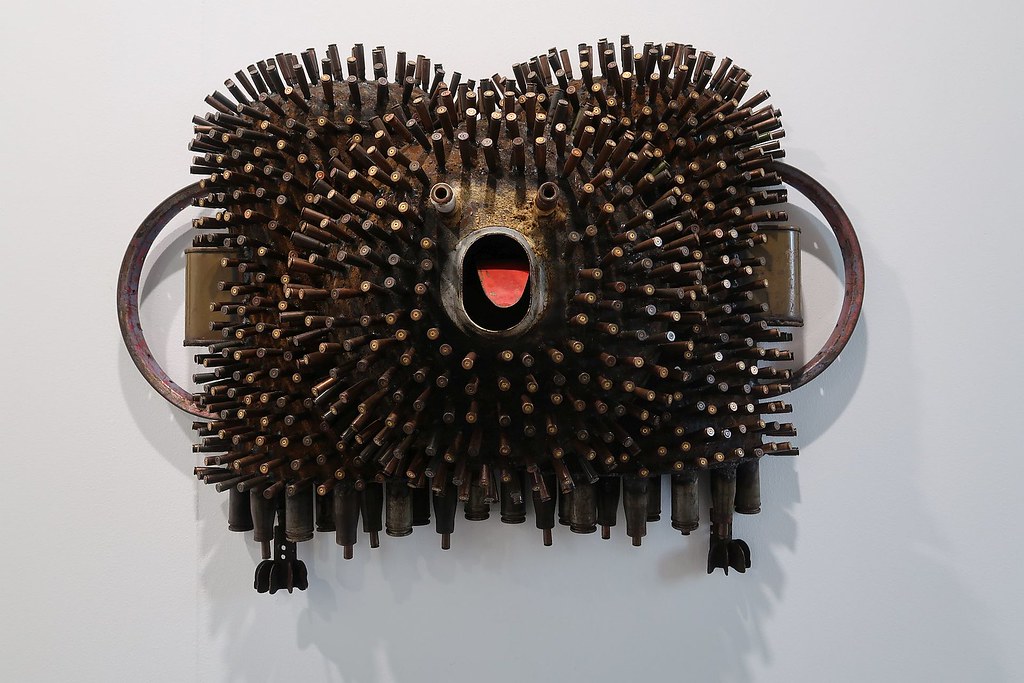

Both O Caogido (8.3.14) and The Processors of the Present (8.3.15) are examples of Mabunda's masks. The masks were based on traditional ethnic African masks from local regions and historical definitions. Both masks incorporated bullet casings and other scrap metals welded together. In addition to the weaponry, he bought scrap metals from the sellers on street corners. Mabunda did not use paint; instead, he let the natural colors of the used metals define the colors. The projecting bullet cases in each mask created depth, dimension, and meaning to the mask.

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): The Processors of the Present (partial image) (2019, scrap metal and weapons, 220 x 84 x 84 cm) CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): The Processors of the Present (partial image) (2019, scrap metal and weapons, 220 x 84 x 84 cm) CC BY-SA 4.0 Chéri Samba

Chéri Samba (1956-) was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo (8.3.16), where his father was a metalsmith, and his mother worked in farming. Samba's first name was David Samba; however, the country banned Christian first names, so he changed to Chéri Samba. Although his parents were connected to the Kongo culture, he adopted the Kinshasa culture. Samba attended Catholic school as a child and spent most of his time drawing, an activity disapproved by his father. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the largest countries in Africa, an area inhabited by the Bantu about three thousand years ago and ruled from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries by different kingdoms. In 1885, as part of the European exploitations of Africa, Belgium declared the region belonged to them. Belgium exploited the natural resources, caused the death of millions of people from disease and military control, and established Catholicism as the main religion. The country first became independent in 1960 and was decimated by multiple civil wars. The 2018 election brought a relatively stable government.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Samba went to the capital city in 1972 when he was only sixteen to work as an artist. His first jobs included being an illustrator for a magazine, a billboard painter, and designing comic strips. Samba melded the skills into his art style as he began painting and helped start the "Popular Painting" school. He was aware of the constant disruptions in the country, and most of his art is based on poverty, corruption, AIDS, and politics while educating people about the African culture. Samba used color as a vehicle to express an idea, frequently using himself as the model. He stated, "I appeal to people's consciences, artists must make people think."[6] He painted multiple versions of J’aime la Couleur (I Like Color) (8.3.17). He holds a brush in his mouth in this work, the bright colors easily seen from afar. The vivid blue sky provides a contrasting background for the image. The end of the brush explodes in colorful pink flowers, a message of preserving the planet. He also included glitter in this painting and his others because glitter enhanced the color. Samba saw color everywhere and felt it was part of life and focused on his paintings.

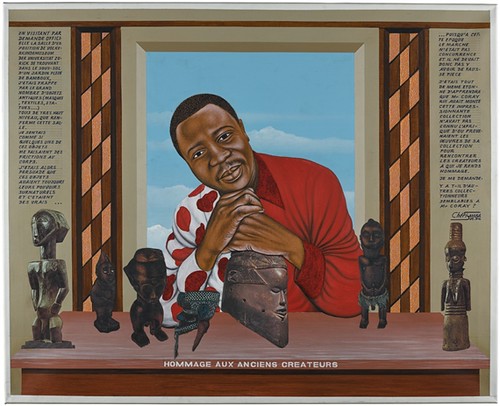

Hommage Aux Anciens Createurs (8.3.18) contains an image of Samba in the center dressed half in modern clothing and half in traditional dress. He frequently used text in his work, and in this painting, he scribes about the different political and social issues confronting society. The title translates as Tribute to Ancient Creators. Along the bottom half of the painting are other traditional figures carved by long-ago artists, connecting to the artistic expression of ancestors. Samba also included the vivid blue sky seen in most of his paintings.

Yinka Shonibare

Yinka Shonibare (1962-) was born in London, England, the son of Nigerian (8.3.19) parents. When Shonibare was three, they moved back to Nigeria, his father practicing law. Nigeria is the most populated country in Africa. The country has been inhabited by different kingdoms for millennia, the Nok unifying the region in the fifteenth century BCE. British colonialization began in the nineteenth century CE until 1960, when Nigeria became independent. The government changed based on coups and civil wars, with multiple attempts at democratic governments disrupted by tribalism, religious persecution, economic control, and political persuasions. Shonibare returned to England when he was seventeen to study. However, a year later, he contracted an inflammation in his spinal cord, paralyzing one side of his body. Shonibare continued his studies at art schools until he attended Goldsmiths and graduated with an MFA with some Young British Artists.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Like many other African artists, the problems of colonialism and civil wars influenced Shonibare's work. He traveled back and forth between England and Nigeria, speaking both languages. He considered himself a citizen of the world and freely used ideas he saw in other places. His major works are sculpted figures without heads, dressed in vibrant colors and patterns. One of Shonibare's major series is the Age of Enlightenment, based on the eighteenth century and the period's arguments and development for the nineteenth-century conquest and colonial domination. The French chemist Antoine Lavoisier (8.3.20) is dressed in typical clothing of the period, only the material made from vibrant colors of African fabrics. The chemist is symbolic for believing the concept of European superiority over others because they made scientific discoveries and were more technologically advanced. Therefore, Europeans were better than other races. Although the chemist is in a wheelchair, he was not actually in one. As with the other sculptures in the series, this one also is headless, a memorial to the explicit brutality of colonialism.

Shonibare created a new series based on the idea of climate change. He used children precariously standing on a globe (8.3.21). The globe is shaded with different colors depicting heat map areas, the regional changes from temperature change. Shonibare strategically used children suggesting today's adults are like children who are "toying" with the globe, ignoring the implications of their actions. The child wears clothing manufactured during the Industrial Revolution, the start of polluting factories.

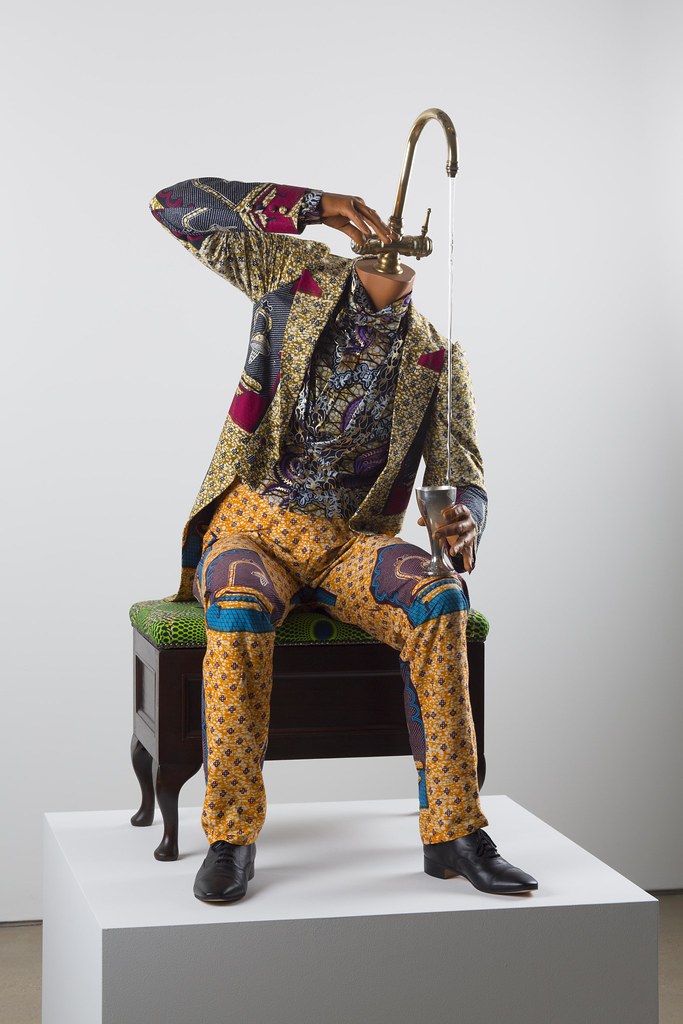

Shonibare used Dutch wax cloth for the clothing of his sculptures. The process of fabric processing was developed in the nineteenth century Netherlands based on traditional Indonesian batiks. They wanted cheap and easily made cloth to export to their colonies. However, the European colonists in faraway places did not like the rough fabric, so it was sold to Africans, where the traders stopped to refuel. In one of the series, Water (8.3.22), the headless man tries to get a drink. His colorful, well-tailored clothing suggests he was a well-off Victorian man. Without a head, his racial identity is unrecognizable, and without a head, the irony of water to drink is visible. Shonibare brought a message of the fragility of access to water in some places, a continuing problem, and a potential trigger for future wars.

Shonibare consistently used the Dutch batik cloth, and his work became identified as African art, although the fabric was not African. Crash Willy (8.3.23) is an example of Shonibare's scenes from Western History. The image of Willy was based on Death of a Salesman when Willy Loman died at the end in a car crash. The once vital person is left as a lifeless form draped over the seat, an arm and leg hanging, unusable. Shonibare said, "Theatricality is certainly a device in my work, it is a way of setting the stage…There is no obligation to truth in such a setting, so you have the leeway to create fiction or to dream."[7]

Julie Mehretu

Julie Mehretu (1970-) was born in Ethiopia (8.3.24), her father, a college professor, and her mother, an American. When Mehretu was a child, the family left Ethiopia in 1977 to escape the civil wars, moving to Michigan. Ethiopia is considered one of the sites where early Homo sapiens emerged during the Paleolithic period. Early Stone Age implements and other remains have been found, documenting the early inhabitants. By the eighth century BCE, an early kingdom was established as one of the first civilizations, leading to other cultures in the region. With the first century CE, the Kingdom of Aksum emerged as the beginning of modern civilizations and great power. Through the centuries until modern times, Ethiopia has been under the control of its rulers instead of colonization, defeating any attempts from outsiders. However, civil wars often erupted between factions, disrupting stability. In the 1970s, the long-ruling Haile Selassie was overthrown, and the new leader trying to change Ethiopia into a communist country generated continual unrest. In 1991, a new government was formed based on a constitution and elections; however, discord still exists in the countryside. When Mehretu's family came to the United States, her father taught at Michigan State University. She graduated from college and attended the Rhode Island School of Design to receive an MFA.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

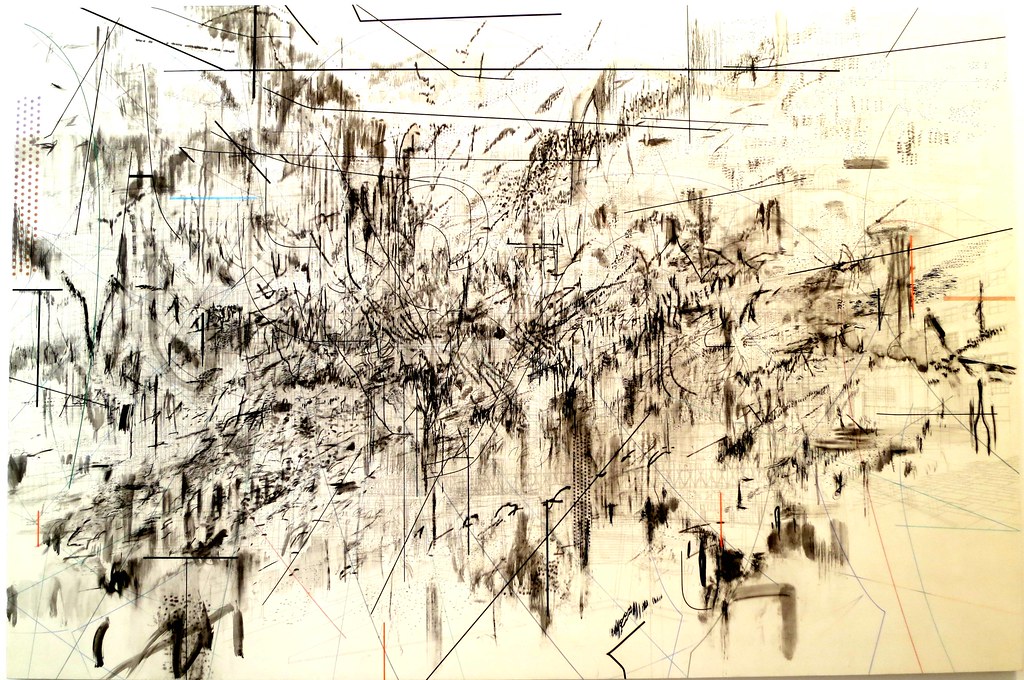

Mehretu's art is focused on large-scale paintings with layered acrylic paint on canvas and other media on top. She bases her work on abstracted images of historical events, geographical formations, or configurations of cities. Her canvases frequently include overlaid images of maps, facades, different charts, or building columns. The noise of the multiplicity of marks on her canvas reflects the speed of life in modern cities. Ra 2510 (8.3.25) is a mixture of ancient and future cities, including the Gates of Babylon and a modern stadium. Mehretu uses different points, vectors, and ink marks overlapping and intersecting. Another diagram partially hides each definition. Her background was simple tones of yellow smeared on before using inks and pencils to add the detailed intersecting lines.

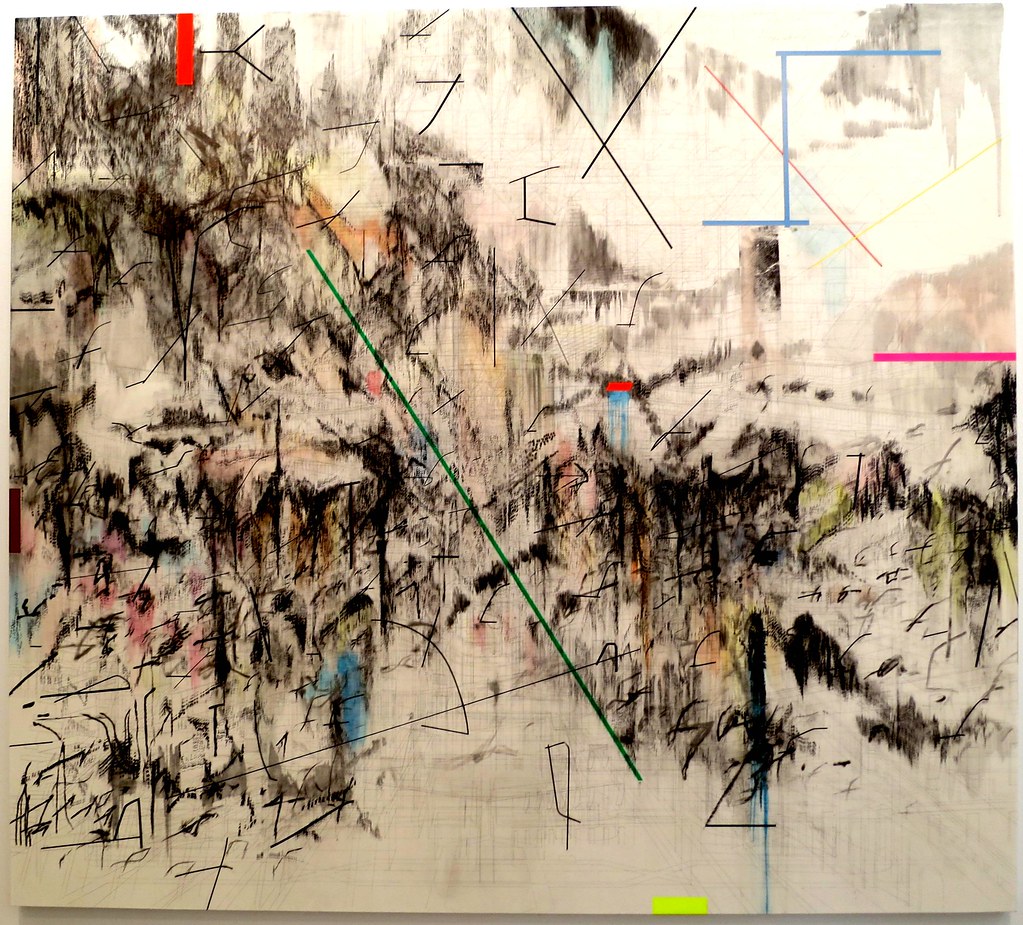

Co-Evolution of the Futurhyth Machine (after Kodwo Eshum) (8.3.26) has floor patterns found in mosques as its basis. Mehretu added geometric lines on top, some overlapping and forming dark conglomerations of intersections in ink representing the densely populated sections of a city. She added colored accents in horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions as the final layers. Mehretu talks about her work as "story maps of no location."

Sokari Douglas Camp

Sokari Douglas Camp (1958-) was born in Nigeria (8.3.27) near the river delta, the town mostly populated with those from the sub-group Kalabari. The group regularly traded with Europeans and had a better economic status than others. Camp was raised by her brother-in-law, Robin Horton, a well-known English anthropologist, and shuffled between Nigeria and British boarding schools. Camp describes her transnational upbringing as: "I was one of those colonial children that were mailed back and forth to school. So did I live in Nigeria? Quite honestly, not really. But then, did I really live in England in boarding school? I'm not really sure about that either. I'm Kalabari."[8] She studied and received her BA from the Central School of Art and Design in London and an MA from the Royal College of Art in England. Camp uses her heritage from the Kalabari for her sculpted steelworks. She creates drawings for her ideas and then decides the scale ranging from small 30 cm pieces to 5 meters. Working with steel is physical, and she cuts and bends her work from sheets of steel or recycled material like oil barrels. The Niger Delta, she was from, is heavily polluted as oil is the main product and oil barrels are everywhere.

.svg-1.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Camp frequently uses Corten Steel, an alloy generally used for outdoor construction. The metal does not have to be painted and rusts when left outside. Her sculpture Corten Head (8.3.28) is made from this type of steel. The rusted head appears woven, giving the figure a lighter appearance. The traditional headdress represents multiple styles, light shining through the openwork of the steel. The statue sits outside of the African Centre in London, representing the people of Africa, watching those who enter.

Accessories Worn in the Niger Delta (8.3.29) depicts the modern predicament of women dressed in traditional clothing. The two women are dressed up, including extravagant gele (head wraps) of gold leaf and jewelry. However, the fancy blue dresses are made from steel, appearing like chain mail instead of comfort. Each woman carries four AK-47s and extra bandoliers of bullets, ladies in fashionable dress, protecting themselves in war-torn regions. Camp shaped the oversized guns from wood and steel.

Asoebi is a traditional Yoruba dress in Nigeria worn initially for ceremonies or funerals when all participants in a family are dressed in matching clothing. The idea of identical clothing expanded beyond the family to all attendants for the occasion. However, uniform dress for a group in social settings led to competition and the mark of possible personal affluence in the quality and richness of the group's attire. Camp was inspired by the importance and love for the occasion, how women decided what to wear, and how they obtained the clothing. The Lace Sweat and Tears part of the title may be comparable to the idea of blood, sweat, and tears as the tradition may be expensive and difficult for some to afford and dress like their friends. Asoebi or Lace, Sweat, and Tears (8.3.30) is part of the African Garden at the British Museum. Made from galvanized steel, the five women are dressed in the concept of Asoebi. They demonstrate the time and money it takes to create and achieve the proper look. The figures wear bright green lacy dresses with highly contrasting pink fabrics. The women wear matching pink haze head ties with multiple layers.

Material Salsa (8.3.31) is made from steel and colored with acrylic paint. The mother and son become an allegory of the relationships within a family and how the dynamics change. The son is a man ready to leave home; his body is separated from his mother as his hand still reaches back. The woman is dressed in typical African dress, the son wearing a Western-style jacket with logos. The mother keeps her eyes on the son as he looks to the future.

Abdoulaye Konaté

Abdoulaye Konaté (1953-) was born in the Republic of Mali (8.3.32) and trained at the local Institut National des Arts de Bamako. He also went to Cuba to study at the Instituto Superior de Arte. Much of the country of Mali lies in the Sahara Desert. Most people live in the areas where the Niger and Senegal rivers run through the country. Present-day Mali was part of the three great empires controlling the lucrative trans-Saharan trade, and the Empire of Mali covered twice the area. In the late nineteenth century, France took control of the region until 1960, when it became independent. Mali has struggled with different governments, coups, and outside attacks. Although much of Mali is in one of the hottest places in the world, the country has large amounts of natural resources of gold, uranium, and other minerals.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

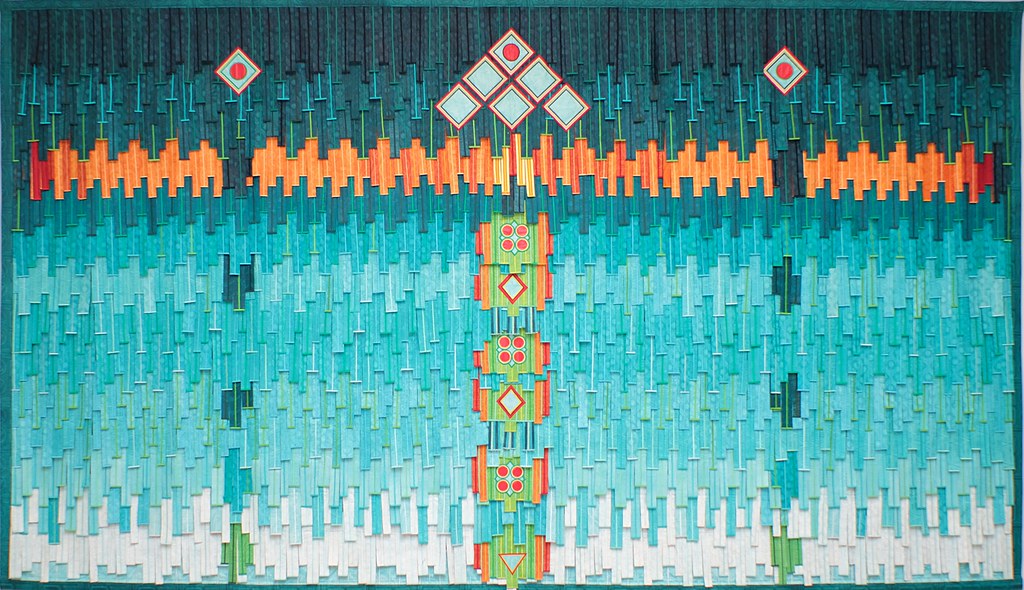

Konaté is a well-known artist in Mali who creates both paintings and installations. When he was a beginning artist, Konaté had little access to canvas and paint, and the closest thing he found was local fabric. His works are significant in scale and based on textile arts, the fabric made in Mali, inexpensive and available everywhere. Textile manufacturing in Mali and other nearby countries is a rich tradition. Some weaving and dyeing of material are supported by individuals working alone or in small groups. Women use raw long-fiber cotton and spin it into strands of fibers ready to be woven. Men on handmade looms perform the actual weaving of the cotton strands. One of the traditional dyes for the material is indigo, a deep blue color. Other fabrics are made, especially Bazin, a heavily polished cotton with a distinctive sheen and multiple colors and patterns. Today the fabrics are made in factory sites. Bazin is mainly used for special occasions. Konaté uses pieces of cotton and bazin and cuts, sews, and dyes the fabric to make his tapestries. His work generally focuses on political and social issues and what is occurring in the environment. Some of the work is specifically targeted at the political conflicts in the Sahel region and the effects of AIDS on the people of Mali. Konaté's work can be abstract or figurative; all his work is labor-intensive and time-consuming.

Vert Touareg (8.3.33) is made of bazin and cut into strips to form integrated patterns. The diamond shape symbolizes harmony while the circle represents the sign of protection, symbols inspired by African spiritualities. Konaté used a spectrum of contrasting colors, including the red, orange, yellow, and white seen in the representation of the Sahel-Sahara triangles. His cut and overlapping panels form rhythmic lines intensifying the movement from the dark blue-green color at the top of the image down to the short melody of white notes moving across the bottom. Unlike oil on a flat canvas, Konaté's work has a presence, movement, and feeling of dimension.

Water is an essential part of life in Mali because of its location and the hot Saharan desert. Ocean, Mother, and Life (8.3.35) reflects the desert's encroachment, the need for water, and the conservation of water. In this work, Konaté uses a different technique. Instead of the small, hanging, and overlapping pieces found in most of his work, he used a flat piece of fabric in this one and cut out and embroidered the fish onto the background. Konaté also added pieces of different indigo-colored fabrics to develop the flow of the water, adding small bubbles floating among the fish. He used a broad spectrum of colors for the fish, illustrating Mali's traditions of colored cloth, a symphony of threads.

Aida Muluneh

Aida Muluneh (1974-) was born in Ethiopia; (8.3.37) however, the family moved a lot, and she lived in Cyprus, Greece, England, Yemen, and Canada. Originally, Muluneh planned to become a lawyer until an art teacher taught her how to use a camera and darkroom for developing the images. Her grandfather in Ethiopia visited the family in Canada and told her to continue following her passion for art. She went to Howard University and received her degree in film and television. Since then, she has worked as a photojournalist and returned to Ethiopia to live and is considered a leading expert on African photography. Muluneh continues to focus on contemporary photos of Ethiopia and portraits of the people.

.svg-1.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

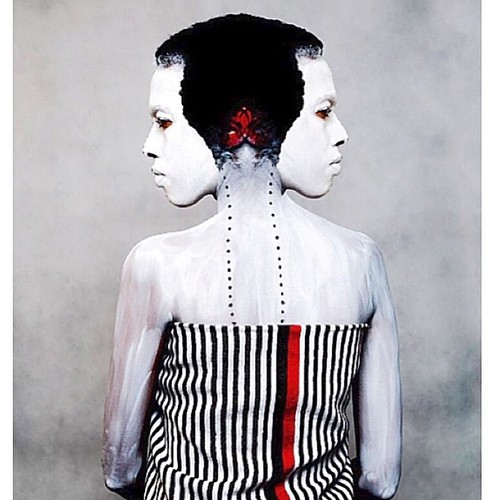

Muluneh combines primary colors in her photographs, not just black and white. The walls of churches in Ethiopia are covered with bright paintings in primary colors and the inspiration for her work. The colors in her work are identifiable from a distance. Muluneh also focuses on women because she thinks the gaze or look of a woman contains power and a universal expression. She starts her concepts with a sketch and thinks about the setting for the photograph, how the set will be designed, what is the appropriate lighting and what is the character of the person she wants to establish. Muluneh is inspired by her culture's traditional dress and ornamentation and tries to incorporate them into her contemporary works.

Muluneh's 99 series (8.3.38) is a set of images of a young woman. Although African, her face and skin are covered in heavy white paint while her hands are dark red. The woman appears to have a ghost-like quality between life and death. Covering one's body and face was common in Xhosa ceremonies when men applied white clay to themselves. Muluneh said the 99 Series captured "the story we each carry, of loss, of oppressors, of victims, of disconnection."[9]

Muluneh also explored the links and changes between generations and how personal and national experiences affect the connections. She said, "As women, especially as African women, we forget—and the world forgets—our positioning in history and religion and culture."[10] This work is inspired by the Amharic saying, Temetaleh beye, Sai Mado, Sai Mado, ye liinete eyene mouma ende beredo (As I waited for you in a distant gaze, my eyes melted like ice awaiting your return). In Sai Mado's (8.3.39) (The Distant Gaze) work, the broken glass reflects the past and present. The woman is wearing a bright red pants suit; the chair is positioned, so her profile is visible. Part of her face and hands are painted red. The red stands out from the black and white checkerboard floor patterns and the blue and white cloud-filled sky. The woman dominates the image and stands out despite the noise from conflicting colors and patterns.

Pascale Marthine Tayou

Pascale Marthine Tayou (1966-) was born in the Republic of Cameroon (8.3.40) and studied to become a lawyer. He left law and wanted to be an artist in 1990 during the political chaos and social turmoil, especially the scourge of the AIDS epidemic. Cameroon was long inhabited and had multiple powerful chiefdoms. The region first became a German colony in 1884 until after World War I, when it was divided between England and France. Both colonizers left Cameroon in the early 1960s when an independent republic was formed. Different groups have continued to cause unrest in the country. Tayou started by showing his work in Cameroon, quickly followed by shows in European countries. Tayou is known for his sculptures and installations using found and cast-off materials. Art became a survival process for him to express himself. He also learned to live in a diverse world, from his native country's traditions to the requirements of the Western world, viewing art as a connection through the global village. Tayou said, "I'm living simultaneously in both worlds; traveling from Africa to Europe is for me like traveling from city to city. My tradition is the human tradition."[11] Tayou focused his work on the exploration of the global village.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Tayou continues to explore his African roots through different heterogeneous methods while still integrating the influences in the world on humanity and nature. Le Verso Versa du Vice Recto (The Back Versa of Vice Recto) (8.3.41) demonstrates Tayou's use of materials. Versa and recto refer to the front and back of a sheet of paper. It also applies to an open book's right- and left-hand pages. Tayou recognized the amount of paper globally, its effect on trees as a base material, and the debris left in landfills and roadsides. The huge elephant-like character is made from thousands of narrow paper strips from computer listings. Extra paper strips continue to spill out from the creatures' legs as the administrative system grows along with the mounds of paper it creates. The monster represents the excesses of information from the corporate world.

The immense apparatus called Reverse City (8.x8.3.42) was installed in a small village, a collection of massive colored pencils. The pencils are hanging upside-down and vertically attached to a stainless-steel frame. Although two meters above the ground, the pointed ends of the pencils are aimed towards the visitors standing on the ground. When looking up, the viewer feels a perception of awe and yet fear. Each pencil is a different length and is etched with distinctive names of countries. Tayou created an impressive, colorful world of a global village; however, the point of the pencil stands ready to threaten humanity.

Tayou's installation, Plastic Tree (8.3.43), presents branches jutting out from the white wall, protruding into the viewer's space. Each of the branches extends at diverse lengths. Instead of leaves, the branches have vibrantly colored plastic bags coarsely tied to each branch. The effect of the installation is a statement on consumerism, the pollution resulting from the use of plastic, and the urban grime of continual waste. The trees and plastic bags also exhibit the artistic integration of the natural material of tree branches and the opposing colorful medium of the bags.

Mounir Fatmi

Mounir Fatmi (1970-) was born in Morocco (8.3.44) nearby the established Casabarata flea market. His mother sold children's clothing at the market, and Fatmi spent his time going through the streets and observing the myriad of objects and building architecture in the area. Morocco is a country inhabited by humans over 90,000 years ago. In 788 CE, the first Moroccan country was established and ruled over the centuries by independent dynasties. Morocco is strategically located along the trade routes and has always had a diverse population. The Europeans did not control the country until 1912, when Spain and France divided control of the region. In 1956, Morocco became independent under the mix of a king and elected government and has been relatively stable since then. Fatmi went to the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome to study art. When he returned to Morocco, he rekindled his interest in historical and religious concepts and how they were defiled and disassembled by over consumerism. He became one of the Arab artists who explored the intersection of conceptual art and cultural identity.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

Maximum Sensation (8.3.45) are skateboards covered with prayer rugs. The original intention of the rug changed to use as the cover for the skateboard, both familiar items now repurposed. The rugs have complex patterns and colorful designs. The skateboard is counter-cultural to the seriousness of using a prayer rug for worship. A person preparing to pray removes their shoes before stepping on the prayer rug while the skateboarder wears dirty shoes to step on the rug-covered board. The sacred loses its purpose and design. Reviewer Blaire Dessent stated, "In the case of Maximum Sensation, it's a reminder that cultural codes have shifted. Identity cannot be defined by only one construct. Stereotypes need to be checked and assumptions reconsidered."[12]

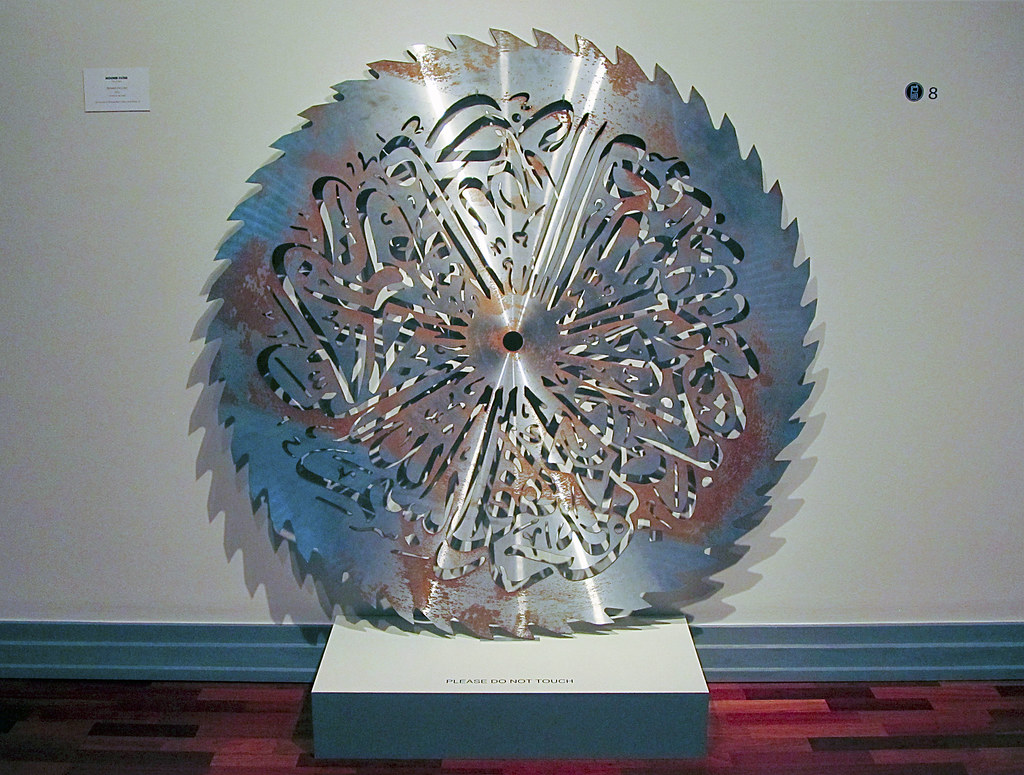

When Fatmi works with his multiple disciplines, including video, painting, and sculptures, he uses an ordinary object to intersect and conflict with religion, politics, and ancient history. Between the Lines (8.3.46) is made with a standard saw blade surrounded by menacing looking and dangerous sharp teeth. Inscribed on the blade are Islamic poems based on messages of peace. Fatmi changed the text from religious doctrine to an artistic and decorative carving on the hard steel blade. The delicate, curving lines of the inscribed text also change the cold steel blade into a lace-like object. The text and the blade lost their original meaning and feeling and became different configurations and connotations

Athi-Patra Ruga

Athi-Patra Ruga (1984-) was born in South Africa (8.3.47) and studied at the Gordon Flack Davison Design Academy. Apartheid was still part of the country when Ruga was a child, and the dystopia and structures of gender and race restrictions, and bias, became part of his artwork. He used fashion and body positions in unusual urban settings, a clash of the definition of social normalcy and individual choices. Ruga incorporates videos, photographs, colorful tapestries, and clothing to create alternative identities and criticize the prevailing political and social status quo. He places the characters in a utopian universe as he critiques current systems and presents a potential humanist view in the future. Ruga is not afraid of tackling the challenging issues of sexuality, queerness, AIDS, or personal identity.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350)

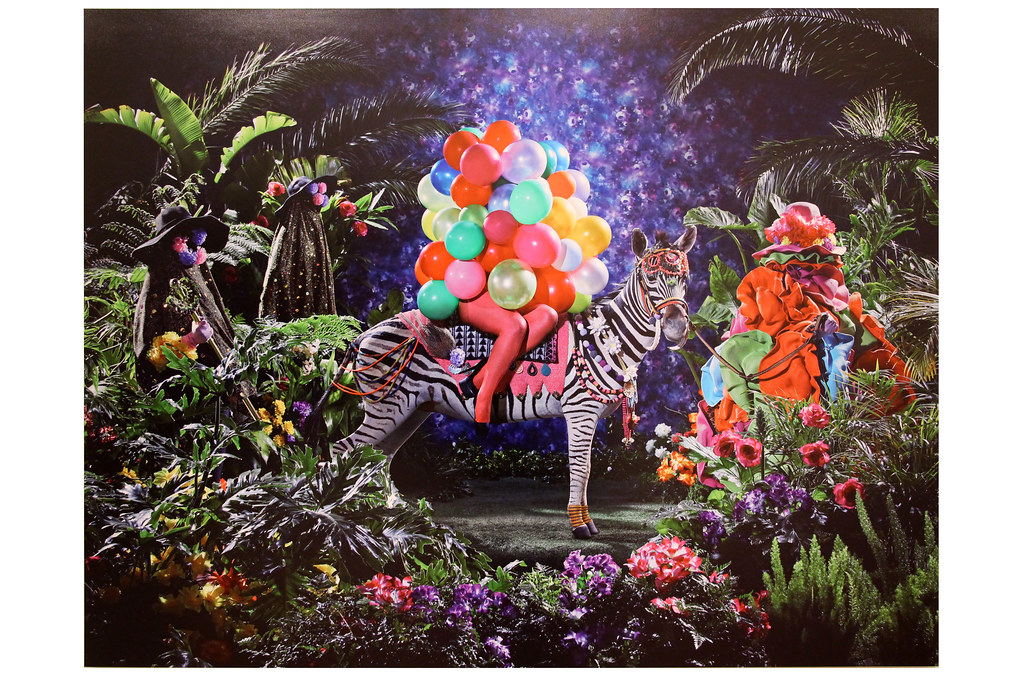

In his first main solo UK exhibition, Ruga brought different series together for his surreal collection of unusual characters. He uses many of his artistic methods; drawings, sculpture, and photography, along with the colorful petit point tapestry. The entire exhibit immerses the viewer in an allegorical world free from political, social, and cultural systems. The Knight of the Long Knives I (8.3.48) is part of Ruga's series Future White Women of Azania, a story based on the black queer women found in South Africa. On the left side are two abo dade (sisters), women able to have a baby by thinking about it. The rider is the future white woman sitting astride the zebra; the filled balloons, the sound of latex, and the popping of the balloons are all part of the cleansing of prejudices. The zebra is decorated like animals used in processions. The background in the image is filled with plastic flowers and cheap fabric mimicking an English garden. The colorful, bucolic scene belies the meaning of the Knight of the Long Knives, as the knights were the beginning of Hitler's Gestapo in the 1930s, a group Ruga compared to those supporting South Africa's genocidal laws.

At the End of the Rainbow We Look Back (8.3.49) is based on movements done by the Paris Folies Bergerac dancers. Ruga used his own body for the pose. The figure is life-sized and includes an extra breast. The entire sculpture is covered with crystals, pearls, gold, and an assortment of artificial flowers. He placed the statue on a round mirrored surface with additional lights encircling the figure, enhancing the figure's reflective quality. Ruga liked to use pageantry, humor, color, and fashion in the fight against racism, homophobia, and misogyny.

Jems Robert Koko Bi

Jems Robert Koko Bi (1966-) was born in the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire (8.3.50) and, as a student, attended the University of Abidjan in the Ivory Coast. He studied Spanish history for two years before switching to art. Jems Robert Koko Bi then graduated from the Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf in Germany. Historically, the Ivory Coast has been part of multiple kingdoms and empires until 1843, when it became a protectorate of France and an official colony in 1893. They achieved independence in 1960 and had a series of different presidents and constitutions. After two separate civil wars, the country is relatively stable. Jems Robert Koko Bi is a sculptor and performer and a significant artist in the Ivory Coast. He works in wood to create shapes appearing both abstract yet figurative. His primary technique is to use a knife or chainsaw for larger pieces and even fire to achieve the shape and color of a block of wood. The fight for power, the results of slavery, and the migrations of people are recurring themes used in his work.

.svg.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=350) Figure \(\PageIndex{50}\): Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{50}\): Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, CC BY-SA 3.0Jems Robert Koko Bi lives and works in the Ivory Coast and Germany. Because he works with old wood, he keeps piles of different timber pieces stacked around his workshop. He never cuts down a tree; instead, he searches for old, dead trees. Using machines and chain saws in his workshop gives the workshop has the smell of sawdust and gasoline. As he works on the wood, it becomes transformed into an image, the dead tree gaining another life and generating a new story. Jems Robert Koko Bi feels he integrates part of himself into the wood and the strife-ridden history of Africa. He explained how wood "frees the spirit, makes it possible to play with multiple forms that highlight both plenitude and emptiness, the positive and the negative, contrasts which, in turn, give rise to countless new potential avenues for thought."[13]

The giant head, Mandela, 2700 Pieces of Life's History (8.3.51) was made from pieces of dead spruce trees cut into pieces and fit together in the sculpture. He burned some of the pieces of the wood before adding them. Mandela spent 27 years in prison, and the statue has 2,700 pieces of wood in the work. Mandela was arrested for multiple reasons, including treason, illegally leaving the country, and sabotage. After his trials, he was sentenced to life in prison. When apartheid was dismantled, Mandela was released from prison and established a multiracial government. Eventually, he was elected president of South Africa. The sculpture symbolized the fight for freedom.

Exodus (8.3.52) is a display of legs spread across the site. Jems Robert Koko Bi was interested in the history and migration of people and believed they were grounded by their feet. Their experiences were kinetic, the feelings of touch and motion on the land they walked. Culture in Africa is connected to the earth; people walked and moved and sang and danced as part of important cultural activities and experiences. The sculpture allows the viewer to determine the actions of the legs; are they running, walking, escaping, what are the people's emotions; excitement, fear, or other?

By the 1980s, when most countries were independent of foreign government controls, new political changes also released artists from constrictive rules of Western art. With modern media and travel, artists have embraced globalization. New and contemporary art styles continue to be developed across African countries.

[1] Retrieved from https://newafricanmagazine.com/19828/

[2] Retrieved from https://www.artsindustry.co.uk/featu...don-for-africa

[3] Donvé, L. (2006). Willie Bester: Art as a Weapon, Awareness Publishing Group, p. 34.

[4] Retrieved from https://www.theartblog.org/2007/08/r...-some-details/

[5] Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world...76a_story.html

[6] Retrieved from https://www.artsy.net/artwork/cheri-...r-i-like-color

[7] Retrieved from https://www.stephenfriedman.com/exhi...-the-rise-and/

[8] Collier, G. (ed.), Delrez, M. (ed.), Fuchs, A. (ed.) (2012). Engaging with Literature of Commitment. Volume 1: Africa in the World (Cross/Cultures – Readings in the Post/Colonial Literatures and Cultures in English, Rodopi, p. 242.

[9] Retrieved from https://www.kinfolk.com/aida-muluneh/

[10] Retrieved from https://africa.si.edu/collections/ob...13776220&idx=0

[11] Retrieved from https://www.thedonumestate.com/art/artists/20

[12] Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/openc...objects/197366

[13] Retrieved from https://africanartagenda.tumblr.com/...te-divoire/amp