4.2: Abstract Expresssionism (Late 1940s-1960s)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174426

Introduction

In New York City during the late 1940s, the beginnings of a new style of art emerged, radical new directions in art. The artists associated with the Abstract Expressionists were not all similar in look as they all developed the concept of spontaneity and improvision. Their work was dynamic and gestural, highly abstracted. The artists were influenced by earlier movements of Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism, as those movements changed the concepts of art. The crisis and chaos of World War II exposed the brutality and irrationality of humankind, and the young artists wanted to bring their expressions and feelings into new art. Many European artists migrated to the United States during and after the war, bringing additional possibilities and influence. The artist wanted their direct feelings and gestures to be part of the process of their work, not a method to reproduce an object, instead of the canvas as part of the event of painting. The new movement also shifted the art world's focus from Europe to New York after the war and a new generation of artists. In the new world of Abstract Expressionism, artists flocked to Lower Manhattan in New York, interacting on the streets, cafes, and jazz clubs. They even had their own Eighth Street Club, where they met to trade ideas. Most Abstract Expressionist artists lived in New York during this period as the style spread throughout the country.

Some referred to the new movement as action painting. Artists worked on enormous canvases not attached to an easel. In 1962, Clement Greenberg said, "If the label 'Abstract Expressionism' means anything, it means painterliness; loose, rapid handling, or the look of it; masses that blotted and fused instead of shapes that stayed distinct; large and conspicuous rhythms; broken color, uneven saturations or densities of paint, exhibited brush, knife, or finger marks."[1] The figure's role in action painting was perceived as the destruction of the figure, the image secondary. The application methods became part of the new styles ranging from dripping and pouring paint onto the canvas to painting figurative imagery. Abstract Expressionism supported the concepts of non-representational art, mingled colors, and shapes formed through emotion. The artists used rapid brushstrokes, dripped, poured, threw, or splattered paint on large canvases in seemingly random order, the whole canvas of equal importance.

Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell (1925-1992) was born in Chicago, Illinois, and attended classes at the Chicago Art Institute as a child and teenager. She earned a BFA and MFA before she moved for a short stay in New York City. After the war, Mitchell went to Paris on a travel fellowship and met an American publisher she subsequently married before returning to New York. In the 1950s, Mitchell was part of the artists who spent time in bars and clubs, discussing art as part of the Abstract Expressionist movement. She became friends with many artists, participated in shows, visited each other's studios, and participated in the New York art scene. Mitchell's first solo exhibition was in 1952, a time she also divorced her husband. During this period, women artists remained marginalized; however, Mitchell was one of the few women in the group in weekly meetings on East Eighth Street to discuss art.

Mitchell's work always remained abstract, usually on large, expansive panels. Landscapes were her primary source of inspiration. Throughout the 1950s, she established her style using counterweighted lines and layers of color, forming emotions into her work. She used white backgrounds on her canvas and applied bright chunky colors. Art historian Linda Nochlin stated, the "meaning and emotional intensity [of Mitchell's pictures] are produced structurally, as it were, by a whole series of oppositions; dense versus transparent strokes; gridded structure versus more chaotic, ad hoc construction; weight on the bottom of the canvas weight at the top; light verse dark; choppy versus continuous strokes; harmonious and clashing juxtapositions of hue—all are potent signs of meaning and feeling."[2]

In the 1960s, her father died, and her mother was diagnosed with cancer; Mitchell's work was based on a somber palette. She also started to hang multiple canvases by each other and painted her images across the panels. Mitchell moved to a small town in France near Monet's home, leaving her friends and the art community in New York. Throughout her career, Mitchell worked with pastels and oils and was also a printmaker and book illustrator.

Ladybug (6.2.1) appears spontaneous; however, Mitchell judiciously planned her application of paint. Using broad brushstrokes, she built layers of different hues of colors letting the excess paint dribble down the canvas. Colors are overlapped, some of the layers built up, others formed spots. When she created this painting, Mitchell carefully applied the paint, respecting the relationship between each color and how much paint was part of the brushstroke. Like her contemporaries, she did not approach the work as a compositional image; instead, each stroke became part of the overall image.

My Landscape II (6.2.2) appears as a wide window opened to the exceptionally colored garden. When Mitchell created this image, she lived in France, and the house had a view of the river and the immediate surrounding landscape. The bright blues anchor the paintings as longer green lines appear as vines and leaves. She covered the canvas with complex brushstrokes and colorful places of raspberry and yellow spaces.

In the polyptych Quartet II for Betsy Jolas (6.2.3), Mitchell created a feeling of the expansive fields. White, greens, violet, and blues are applied with thick brushstrokes of paint interspersed with running drips. In some areas, the sky appears to be shining through; other regions are covered with dense vegetation. Her limited color palette enhances the feeling of an overgrown garden.

Janet Sobel

Janet Sobel (1893 – 1968) was born in Ukraine as Jennie Olechovsky. After her father was killed in the Russian pogrom, Sobel moved with her mother and siblings to New York City. When Sobel was sixteen, she married and had five children. She didn't start to paint until 1939; her son bought her art supplies and helped her develop her skills. Sobel frequently used music for her inspiration, filling the canvas as she worked. During World War II, she was horrified by stories of the Holocaust, reviving the trauma of her youth and the pogroms again Russian Jews before she came to the United States. Sobel's work is often considered the forerunner of Abstract Expressionism and significantly influenced Jackson Pollock and his drip painting method and overall coverage. Sobel was initially successful in an early 1945 exhibition. However, her career waned when a few critics called her work too primitive and deemed her a housewife who painted. Critics at the time were very powerful and could make or break a career.

Sobel invented her painting process and poured paint on a canvas, tipping the canvas, so the paint ran in different directions, also blowing wet lacquer. Sobel used the enamel paint her husband used to make costume jewelry. The enamel paint was fast drying and displayed a jewel-like finish. The canvas in Milky Way (6.2.4) was covered from edge to edge as she also incorporated drips as spalts and lines from her brush. At first glance, it appears Sobel used a limited palette; however, close observation reveals a broad spectrum of colors; lilacs, red, orange, yellow, blue, gray, and brown. Some of the paint was applied with a glass pipette, blowing lines as she moved. Areas of the painting appear cloudy yet tied together by tapering lines. Her work was ignored for decades until the late 1990s, when this painting was included in a show of women artists.

Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock (1929-1956), the youngest of five boys, was born in Wyoming. When Pollock was ten months old, his mother took the boys to California, where they stayed. He was not successful in high school; instead, he traveled with his father, a surveyor. Pollock was inspired by the murals of the Mexican muralists, especially José Orozco. By 1930, he went to New York City with one of his brothers and studied with another Mexican muralist, David Siqueiros. During the 1930s, he worked on murals for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). At a workshop, Pollock learned experimental techniques to use liquid paint, inspiring him to develop his well-known drip method. He also attended a Picasso exhibition in 1939 at the museum, appreciating the power of expressive European modernism. During World War II, Pollock had successful exhibitions, much of his work influenced by Picasso and Surrealism. He married Lee Krasner in 1945, an artist who also influenced Pollock's career. Pollock and Krasner moved to Long Island, and Pollock used the barn as his studio while Krasner painted in a bedroom in the house. He grappled with alcoholism most of the time, enhancing his volatile behavior. In 1956, as he drove along a winding road while drunk, he crashed into a tree, killing himself at the early age of forty-four.

After the war, Pollock's work in the late 1940s revolutionized the potential of the new styles to follow. He did not follow conventional standards or use an easel. He laid large canvases on the floor and started dripping and splattering paint around all sides of the canvas as he walked around the canvas. He used resin-based paints, old, stiff brushes, sticks, or syringes to throw down the paint. He did not want to illustrate objects in the natural world; he wanted to create a non-representational impact and be part of the ritual of painting. Pollock avoided any specific points of emphasis, only forming unique patterns as the paint was applied. He stated, "The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through."[3] Pollock's emergence as a significant artist of the period was created when art critic, Clement Greenberg, decreed Pollock as the mastermind of the new American art. The pronouncement from this influential art critic shifted the ideals of the art world and ensured Pollock's success.

Pollock traveled through the western states with his surveyor father and witnessed multiple Native American rituals, including the sand painters who created their work as a spiritual event. Pollock said he did not follow the sand painter's process; he believed the concepts were in his subconscious. Guardians of the Secret (6.2.5) reflect Pollock's synthesis of mythology and ceremonial practices. The abstracted figures on the sides face the symbolic and heraldic forms between them. This painting was part of his first exhibition, created before his more well-known drip method.

The Key (6.2.6) was part of Pollock's Accabonac Creek series, named after a small stream. The painting maintains some of his early interest in Surrealism. He laid the canvas on the floor and painted from every side as he walked around the canvas expressing his interest in spontaneous painting, unplanned and generated from his subconscious and the actions of the paint. Pollock completed this painting the year before he started his drip methods.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The Key (1946, oil on linen, 149.8 x 208.3 cm) by Ed Bierman, CC BY 2.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The Key (1946, oil on linen, 149.8 x 208.3 cm) by Ed Bierman, CC BY 2.0One: Number 31 (6.2.7) is one of Pollock's most significant paintings and is considered his masterpiece based on the innovative drip technique. He worked on the methods for three years before he started this painting. Pollock laid the enormous canvas on the floor to work and dropped, dripped, or dribbled paint onto the canvas, sometimes even throwing paint directly from the can. He even punched holes in paint cans letting the paint run out. Some of the paint splashed outward, forming pools of color and splashing droplets. He used somber colors on the off-white background. The long, looping cords of different colors move around the canvas, animating the painting, forming thick and thin lines. Pollock said, "On the floor, I am more at ease, I feel nearer, more a part of the painting since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting."[4]

Lee Krasner

Lee Krasner (1908-1984) was born in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents were Jewish immigrants who came from Ukraine to escape the Russo-Japanese war. After high school, Krasner always wanted to be an artist and went to a technical art school, learning to copy the old masters and produce anatomically correct images. Unfortunately, few paintings are left from her early career because a fire destroyed her work. The Museum of Modern Art opened in 1929, and during the 1930s, Krasner attended classes in modern art ideas, leading her to question her work and modernize her style. She worked for the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (WPA), painting murals. By 1940, Krasner joined the abstract artists' group, meeting many new artists, including the beginnings of her relationship with Jackson Pollock. Krasner's work became very abstract, part of her continual reinvention as she worked with paint, charcoal, and collages. She frequently cut up her work to use in other collages or even destroyed her work if she was not satisfied. Today, very little of her work survives. In 1945, Krasner married Jackson Pollock, a tempestuous relationship (Pollock was considered an alcoholic). When they moved to Long Island to escape the city influences, Krasner worked on collages, even using parts of Pollock's discarded work. Unfortunately, in 1956, Pollock died in a car crash. Krasner moved out of her small bedroom studio to the big studio Pollock used in the barn, where she started working on her more expansive canvases. Her work was not well-known, and she had few opportunities until the death of Pollock.

After Krasner moved into Pollock's grand studio in the barn, she used huge pieces of canvas for her work. She created Polar Stampede (6.2.8) at night when she had insomnia. Many historians believe this was her release from Pollock's control after his death. Because she painted at night in dim light, she did not see the colors very well, and instead of her usual vibrant colors, she used browns, grays, and whites. Although the painting might be reminiscent of Pollock's style, she exhibited control that Pollock lacked.

In Another Storm (6.2.9), Krasner used the brush to scrape across the canvas, letting the paint bleed into the canvas. She also allowed the unpainted sections of the canvas to show, not compelled to cover every spot. She masterfully used a palette spectrum from orange to purple, highlighted by browns. Her work did not drip from the brush; the paint was purposefully applied.

Elaine de Kooning

Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) was born in New York, the oldest of four children. Early in her life, her mother supported de Kooning's artistic talents by teaching her to draw images she viewed at museum visits. Unfortunately, her mother was sent to a psychiatric facility when de Kooning was still a child. After high school, de Kooning studied art at different places where one of her teachers introduced her to Willem de Kooning at a time, he was thirty-four, and she was twenty. He taught her art and was a harsh critic, even demolishing some of her drawings. Frequently, he set up a simple still life for her to draw, studied her sketch, and then tore it up. They married in 1943 and shared a loft and studio space while they carried on affairs outside of the marriage. Willem de Kooning even had a daughter with another woman. Both of de Kooning's battled with alcoholism and separated in 1957. Elaine de Kooning stayed in New York City, living in poverty. They were separated for almost twenty years and reunited in 1976. She was considered an accomplished artist and belonged to the Eighth Street Club, a rare ability for a woman. She was serious about her work but continued to promote her husband's work first; she believed he was a genius. As women continued to be marginalized during the Abstract Expressionism movement, de Kooning signed her works with her initials, letting her husband use the de Kooning name. She also taught art at different schools and wrote articles for art magazines.

De Kooning used various styles in her art ranging from abstract to figurative and creating a diverse body of work. She believed static styles could imprison one's creativity, and she cared more about the character of her work. De Kooning did not create a pure abstraction; instead, she integrated abstraction with figuration, reinventing the idea of the portrait. She masterfully added slashes of bright color across and outside the lines. De Kooning painted portraits of everyone she met, posing the person in a position to define their characteristics.

De Kooning's most well-known portrait was her commission for President John F. Kennedy. She went to Palm Beach, where the president was staying in 1962, to sketch him in different positions. She used various mediums, pen, pencil, and ink, with charcoal her favorite because it was the fastest. De Kooning was significantly moved by Kennedy and his energy. He also did not sit still and was encircled by activity, a challenge for her because the light and pose were constantly changing. Over two months, she created twenty-three paintings and stacks of drawings, each one different. De Kooning stated she loved "the feeling of the outdoors he radiated" and noted that "on the patio . . . where we often sat . . . he was enveloped by the green of the leaves and the golden light of the sun."[5] This version of John F. Kennedy (6.2.10) is a view of Kennedy seated at a desk with a book in front of him. The colors are contrasting, the yellow paint forming different views over the painting. Kennedy's eyes appear tired, a reflection of the stress of his job. He seems to sit awkwardly in the chair, perhaps trying to adjust the position of his chronic back pain.

Although de Kooning did not have much money, she did visit France and was inspired when she visited Lascaux caves. She created a series of paintings based on views of the cave walls and the animals drawn thousands of years earlier, including deer and bison. In Les Eyzies (6.2.11), she applied forms of red with broad, dense strokes, streaks of blue and purple washing over the outlines of the primitive animals. De Kooning was fascinated by the different scales the original artists used and how some forms were primitive and detailed.

Willem de Kooning

Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), born in the Netherlands, lived back and forth with his divorced parents, leaving school when he was twelve. He worked as an apprentice for other artists while taking classes at the local technical school. In 1926, de Kooning hid as a stowaway on a ship, embarking on the United States. At first, he worked as a house painter, painting on canvas when he had time. De Kooning became part of the modernist set of artists in New York. He started working for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) mural projects; however, he resigned because he was not an American citizen. When he met his wife, Elaine, she was fourteen years younger than him. They married in 1943; de Kooning was working on his original series of portraits. Their marriage was continually affected by affairs (claiming they had an open marriage), arguments, separations, and alcoholism. During the late 1940s, he became part of the New York school group including Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline and their movement of Abstract Expressionism. De Kooning's work moved from figurative to abstraction, a style he continued to use.

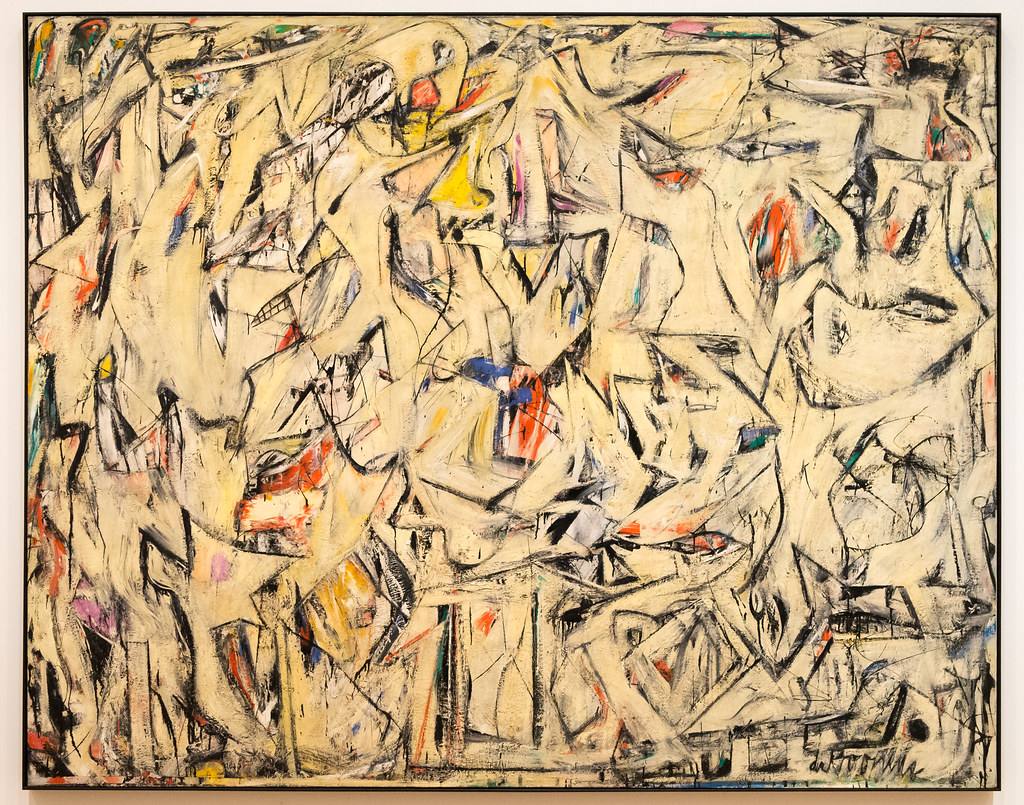

At first, de Kooning based his abstracted work on black and white images, frequently incorporating abstracted female figures in his work. His images of the female were considered his most controversial. De Kooning worked on both paper and canvas, most of his original black and white work on paper. He used multiple types of media; enamel, pastels, oils, applied with broad brushstrokes in layers he sanded, scraped, and drew. He developed curved and straight lines that floated, intersected, and stopped, resembling ethereal-like ribbons as he alternated between vivid colors against areas with quiet tones.

Excavation (6.2.12) was one of de Kooning's largest paintings at the time. He used dark lines to define anatomical parts of birds, fish, and humans, details appearing to move or dance across the canvas. The original image had a white background; age has yellowed the color. The punctuating colors were bright and moved through the canvas; however, the yellowed background now mutes the colors. He created the image by building the surface, scraping it, and adding more layers.

A Tree in Naples (6.2.13) was part of his abstracted landscapes. De Kooning applied the paint with thick, broad brushstrokes with colors found in nature. He said his landscape paintings were inspired by the vistas he saw on open roads.

De Kooning frequently returned to the female figure as the subject for his paintings. He generally reviewed a figure and made multiple initial studies before he started painting. Many people saw his work as misogynistic, violent, and objectifying women, and others felt the images were dated, a style from the past. De Kooning himself said, "Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented…beauty becomes petulant to me. I like the grotesque. It's more joyous."[6] In Two Women with Still Life (6.2.14), he used light and dark pastels equally instead of employing the usual technique of using the darker colors first and then adding the lighter colors. The two women stand side by side, the still life elements challenging to discern. During a 1953 exhibition, the work was considered unbelievable because of the clashing, garish colors and frantic lines.

Franz Kline

Franz Kline (1910-1962) was born in the coal-mining region of Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, his father committed suicide when Kline was only seven. He went to a high school for fatherless boys before he studied art at Boston University. He went to London for further art education and met his wife. They returned to the United States, living in New York City. Kline's training was based on illustration, and he worked on several commissions for murals. However, he continued to develop a more simplified style influenced by the New York City art scene. By the 1940s, he began to use his signature lines, probably based on suggestions by Willem de Kooning about abstraction. By the end of the 1940s, Kline's work was all non-representational with dynamic lines. At first, he worked only in black and white for almost a decade. By the 1950s, he started experimenting with color in addition to black and white. Kline liked to use solid and gestural lines of black paint against the white background, adding splatters of black to enhance the broad black lines. Unfortunately, he died of heart failure at the summit of his career.

Mahoning (6.2.15) is an extra-large painting with broad, bold black brushstrokes against the contrasting white background. He liked to use house paint because the viscosity was less dense, and the paint could be applied quickly and ran faster. Kline's brushwork is ragged, a result of broad movements by the artist. He glued small sheets of paper on the background before adding paint. The diagonals in the painting escape off the edge of the canvas. Like many of his others, the painting was named after a town in Pennsylvania's coal regions. Perhaps he used black as a reminder of the coal color of his youth.

Blueberry Eyes (6.2.16) is based on dynamic red, black, and green applications. The bold strokes were painted on top of the blue background. Kline said he was inspired to use blue because it was the color of eye shadow his friend wore after she returned from Paris. He brought tension between the color and the brushstrokes of black, color trying to overcome the black.

Helen Frankenthaler

Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) was born in New York City. Her father was a judge for the New York State Supreme Court, and Frankenthaler grew up with a privileged background. She and her sisters were properly prepared for advanced education and professional careers. She frequently studied under well-known artists and graduated in 1949 from Bennington College. She married artist Robert Motherwell in 1958 and divorced him in 1971. Frankenthaler started exhibiting her work in 1951 and by 1959 regularly exhibited in international events and solo shows in many museums and galleries. Frankenthaler was well-known for her paintings; however, she also produced welded-steel sculptures, created illustrations for printing and books, designed costumes for England's Royal Ballet, and taught at different universities.

In 1952, Frankenthaler started her innovative soak and stain method of painting. Using an unprimed canvas stretched on the studio floor, she poured thinned oil paint on the canvas. The paint was so thin, it soaked into the canvas, staining the absorbent canvas. She worked on all sides of the canvas, the thin color oozing across the surface to create a translucent look. As the great swaths of color bled across the canvas, her work almost had a landscape feeling. She believed in the fluidity of paint, not using the motion of a painter as some of the others believed. However, Frankenthaler didn't care about a literal interpretation of her work; she only wanted to create a beautiful picture. Mountains and Sea were three by two meters, and her first large-scale painting using this technique, a method widely acclaimed by her peers. By the early 1960s, Frankenthaler created images with a single stain tone and used acrylic for deeply colored works.

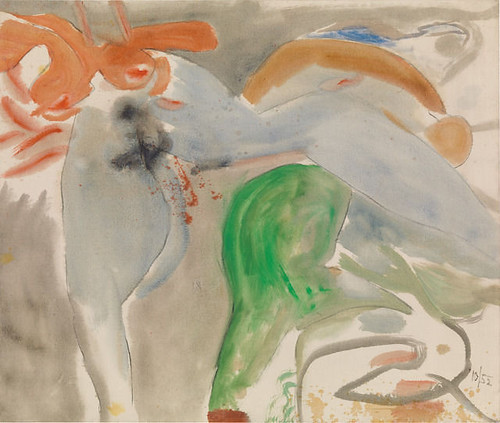

The Scene with a Nude (6.2.17) depicts Frankenthaler's use of the very thin paint flowing in its path on the canvas in the spaces she applied each color. She frequently left sections of the painting without paint, letting the blank canvas as part of the image. The watery gray torso in the upper left corner flows into splayed legs projecting off the sides of the canvas, a hidden eroticism.

Hommage a Chardin (6.2.18) was created with her classic soak-stain method. The saturated color sections contrast to the untreated canvas. The neutral color of grays and browns developed deep color versus the lighter, less intense orange. The scene might be a landscape, fields of different natural plants interspersed with roads, or as Frankenthaler always said, just a beautiful picture.

Frankenthaler went to Arizona and experienced the colors of the desert southwest. In her painting Desert Pass (6.2.19), she denied it was based on her visit to the desert but agrees one's inner psychic musings of physical experiences are reflected in one's artwork. The colors in the painting are very reflective of the colors of the desert, different browns, and yellows in the flat sand through the hills. The sparse green of desert plants is seen in the minimal use of green.

Robert Motherwell

Robert Motherwell (1915-1991) was born in Washington and moved to California, his father the president of a major bank. Motherwell was asthmatic and in poor health in his childhood. His ability as an artist was observable as a child, and he received a fellowship to Otis Art Institute when he was eleven. He graduated from Stanford University with a degree in Philosophy instead of art and was influenced by many modern writers. His father wanted him to go to Harvard and get a Ph.D. for future economic security and was willing to pay Motherwell to attend. So, he went to Harvard and studied before going to New York and Columbia University, where he was encouraged to study art. On a trip to Mexico, he met his future wife and decided to become an artist. Motherwell's group of friends were surrealist artists, and they taught him the concepts of automatism, drawing from the unconscious. By the 1950s, he divorced his first wife and remarried, only to divorce a second time in 1955.

In New York, he was one of the younger artists in the abstract group, which included Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. Motherwell was considered the most articulate and known for works expressing political or philosophical concepts. He believed art was a type of 'mysticism' based on one's imagination to find the unexpressed. Motherwell explained, "The game is not what things 'look like.' The game is organizing, as accurately and with as deep discrimination as one can, states of feeling;…become questions of light, color, weight, solidity, airiness, lyricism, somberness, heaviness, strength, whatever…" [7] Motherwell experimented with paint, brushstrokes, or collages of torn paper. He wanted to express a new art form with multiple materials and concepts and experimented throughout his lifetime.

Motherwell liked to use the concepts of human suffering, loss, and struggles in his work, demonstrating the spiritual journey of life. In Wall Painting III (6.2.20), the six-pointed abstracted Star of David becomes figure-like in counterpoint to the more organic figure on the right. Both figures appear to be moving to unheard muses. Motherwell was not especially religious; however, he used the contrasts of light and dark, stylized and organic, to define the human experience. The painting was made for a synagogue, and the work suggested the Jews' passage as they moved from the blackness of the Holocaust to the freedom of life.

Motherwell created over one hundred paintings he termed funeral songs after three years of the Spanish Civil War. He returned each time to the recurring concept of a black oval he repeated with different sizes and distortions. He placed the contrasting black shapes against a white background. Motherwell often said his image resembled a dead bull's testicles after a bullfight. He stated, "the pictures are also general metaphors of the contrast between life and death, and their interrelation."[8] Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 57 (6.2.21) is one of the paintings in the series and maintains the theme of a horizontal canvas and strong vertical lines. He added ovoid forms in relation to the lines, keeping the strong contrast, colors of life and death.

Grace Hartigan

Grace Hartigan (1922 – 2008) was born in New Jersey, where she married as a teenager. She and her husband planned to move to Alaska; however, they only went as far as California, where Hartigan had a baby and experimented with painting. Her husband was drafted in 1942, and Hartigan moved to New Jersey to learn drafting at an engineering school. She also worked in an airplane factory to support her son, studying art when she had spare time. At one time, Hartigan told an interviewer about painting, "It chose me. I didn't have any talent. I just had genius."[9] She moved to New York City and became part of the downtown scene, one of the artists who all mingled, went to clubs, and influenced the new movement of Abstract Expressionism. Hartigan was significantly influenced by Jackson Pollock's approach and how he immersed himself in his work. At first, she exhibited her work using the name 'George Hartigan", believing a woman's work would not be taken seriously. Hartigan frequently dressed as a man and developed an extensive set of curse words she liberally used. As Hartigan became successful, she used her first name and was noted as one of the upcoming women painters. She also developed different styles, some abstract, some more figurative. Hartigan did not create any specific and identifiable style because she wanted to be free to paint what she wanted. Over time, she married four times, finally moving to Maryland, where she taught at the university.

Essex and Hester (6.2.22) are covered in a dark mottled red with heavy black lines, some colored in with paint. The red background has multiple layers of colors underneath to bring out the intense red color we see today. The black lazy winding lines are drawn in each of the four quadrants and contain specific primary colors. The green slightly above the midline is a complementary color of red, giving it a vibration feeling. The blue color on the lower left is a mixture of cobalt blue and white, giving it a dimensional quality. The other two colors, purple and orange, are secondary colors also mixed with white, loosely applied on top of the red, which peeks through the paint.

When Hartigan was teaching at a college in Baltimore, she noticed how many of the male students were fascinated with motorcycles. She painted Modern Cycle (6.2.23) to reflect the interest of students around her. The motorcycle was portrayed as parts, handlebars, a gas tank, headlights, part of the engine, a woman's legs, the logo. Hartigan even hung a poster of Brando on his motorcycle as an homage to the subject. The painting has exceptionally strong colors, colors found on a motorcycle. Gray-silver, red, and yellows are colors found on a motorcycle, and she used them or designated each part. Hartigan used red sparingly, moving the viewers around the painting. She considered this one of her favorite paintings.

The group of artists who became the Abstract Expressionists came to New York City with the dream of changing the definition of American painting. They wanted to paint something beyond a recognizable image; art based on the truth of one's feelings. Before, Paris was the center of the art world, and this movement brought the center to New York, changing ideals from Surrealism and Cubism to abstract definitions. De Kooning always felt Picasso, and his influence was the competition to beat, and the group in New York achieved the historic change after World War II. Abstract Expressionist artists created a new style; their images were loose and fueled by emotion as color moved around the canvas. The paint was applied with broad, dramatic brushstrokes and thrown, dripped, or poured, covering the whole canvas with movement and action.

[1] Marter, J. Ed. (2016). Women of Abstract Expressionism, Yale University Press, p.17.

[2] Livingston, J. (2002). The Paintings of Joan Mitchell, University of California Press, p. 55.

[3] Retrieved from https://www.jackson-pollock.org/

[4] Retrieved from https://www.jackson-pollock.org/one-number31.jsp

[5] Ward, D. C. (2018). America’s Presidents: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Books, p. 35.

[6] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79810

[7] Retrieved from https://learn.ncartmuseum.org/artist...rt-motherwell/

[8] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79007

[9] Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/blog/eye-level/2008/23/1051/states-grace-remembering-grace-hartigan-1922-2008;