3.4: Cubism (1907-1920)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174414

Introduction

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque created cubism a few years after the opening of the new century. They developed different ideas of how objects or figures were composed, becoming one of the most influential design concepts of the 1900s. Louis Vauxcelles, an art critic, wrote of Braque’s landscape painting as Cubism because the images were formed into geometric shapes or “bizarre cubiques.” The Cubist artists did not believe in the usual standards of how elements appeared in nature or concepts of proper perspective or foreshortening. Instead, they redefined the shapes and objects in their paintings into geometric forms, pulled them apart, and reformed them into overlapping and interwoven sections, allowing different perspectives of the three-dimensional parts of the object. The artists also accentuated the two-dimensional flatness of the surface, obscuring the concept of depth. Braque and Picasso exchanged the traditional perspective of an imaginary distance for a way to hold the eye on the flat surface and experience three-dimensionality differently.

Cubism was comprised of two individual stages; analytical Cubism, the early form of Cubism in muted tones of blacks, grays, or ochres preventing color from interfering with the fragmented objects. The form also had intersecting and overlapping lines and surfaces, with multiple ways to view the object through the assemblage of deconstructed and reassembled parts. The works from 1908-12 used a palette evoking a somber feeling. By 1912 and synthetic Cubism, the shapes were simpler, full of bright colors, and frequently collaged with other materials. The parts were reassembled on top of each other similar to magazine displays on racks with less focus on space and the ability to understand layers of shapes. Collaging and adding other resources like paper or newsprint was one of the more essential concepts of Cubism, ideas that permeated into future modern art. The concept of how to depict space and anything in the space was defined in the Renaissance period. It had been the guiding ideal for artists until the Cubists, who blended space and objects into multiple angles. This section includes:

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) was born in Spain; his father was an artist who recognized the ability to draw in his young son, teaching him to paint at the early age of seven. The family went to Barcelona, where Picasso studied at the art academy. After the academy, he moved to Paris and began to develop one of his many styles. From 1901-04, the first years formed his Blue Period, followed by a year of the Rose Period, when he explored color and its effects on emotions. Picasso believed a painter painted to release their spirits and visualizations, and color followed emotional changes. Then his work evolved into the development of Cubism, searching the interactions of color, lines, and planes. Picasso lived a long life, and his talent and abilities crossed through many different movements. In the late 1920s, he worked with some surrealists and became interested in sculpture in the early 1930s. Picasso was exceptionally prolific and inventive, experimenting with multiple materials and methods and influencing art in the modern world. Over his career, he created more than 20,000 paintings, prints, drawings, sculptures, ceramics, theater sets, and costume designs. [1]

Picasso went to Paris in 1900, where European art was centered, living with a roommate in poverty and occasionally burning a few paintings to stay warm. He sympathized with the people in poverty and how they struggled, and when one of his friends committed suicide, he became despondent, bringing all these feelings to his paintings and the blue period. As demonstrated in The Old Guitarist (5.4.1), he used heavy, dark lines to illustrate the figures or objects; the lines were filled with melancholy hues of light and dark blues. The older man has long arms and gangly legs, appearing near death with little movement, another hallmark of the blue period. The guitar was a standard Spanish instrument, one Picasso was familiar with, used in multiple pieces of his artwork. The dull brown tones of the guitar, the only color change in the painting, added a contrast to the image of the solitary old, blind man who was barely surviving. Some historians believe the painting demonstrated the struggles for survival artists encountered in their careers.

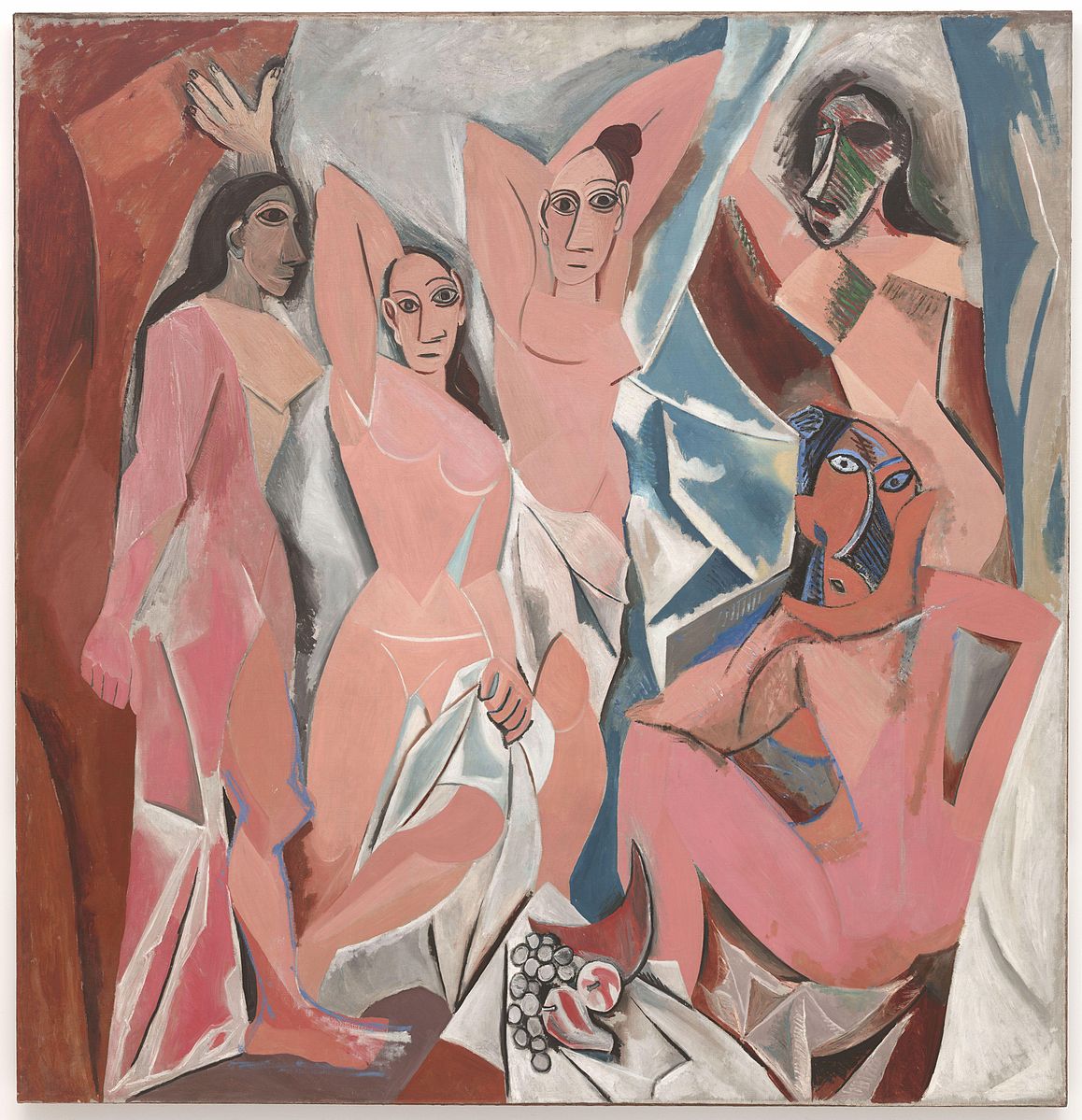

Picasso was also influenced by African art and the angular planes and contours of the statuary and masks he studied at the local ethnographic museums; the influence was reflected in his painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (5.4.2) with their angular proportions. In Barcelona, Avignon Street was then patronized by the prostitutes and their customers. The figures in the painting were larger than life-sized and posed in radical positions. The pink and peach-colored bodies were depicted with angular lines, cubic shapes, disassembled legs, and flat planes. Their faces were simplified, while the two at the far right wore faces based on African masks. The background of curtains resembles shattered glass with sharp angles enveloping the women. Critics, collectors, and friends were appalled by the painting; even his friend Georges Braque was dismayed, exclaiming, “Picasso must have drunk petroleum to spit fire onto the canvas.”[2]

Girl with a Mandolin (5.4.3) depicts a typical Picasso image with muted browns, blues, grays, overlapping strips, and superimposed translucent planes. He used rectangular, geometric shapes for the background and carried them into the girl’s face, neck, and shoulders, building flat planes. The guitar seems almost complete and ordinary except for the twisted form. The painting is an example of the early analytical form of Cubism Picasso and Braque first developed.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_100.3_x_73.6_cm%252C_Museum_of_Modern_Art_New_York..jpg?revision=1)

Woman in a Chemise in an Armchair (5.4.4) was painted with curvilinear lines and flat planes of color, forming a more erotic image, representing the newer concepts of synthetic Cubism. Picasso used different components to describe parts; the breast might be a pencil point, the fingers as tassels. The identities of the parts transformed into other biomorphic shapes, changing the concepts of Cubism as realism intersected with abstraction; the beginning concepts of Surrealism Picasso pursued later.

After World War I, Picasso married his first wife, who was a ballerina. During this period, he helped design costumes and sets for the theatre, elements frequently appearing in future paintings. Three Musicians (5.4.5) was one of his last painted in synthetic Cubism, a large image of three musicians. He used bright colors in flat abstracted geometric shapes almost resembling pieces of cut paper. Each person was depicted as a typical entertainment character, Pierrot, in blue and white clothing, while Harlequin wears diamond-shaped orange and yellow. The dissembled faces appear as mas; their feet and hands vary in shape and size.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_204.5_x_188.3_cm%252C_Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art.jpg?revision=1)

Georges Braque

Georges Braque (1882-1963) was born in France and followed his father and grandfather as house painters. He continued to formally study painting, eventually working with the Fauvists and even exhibited with them. By 1908, he became interested in geometry and the idea of simultaneous perspective. Braque studied light and perspective and how to reduce them to geometrical forms by fragmenting the objects. In 1909, he began to work with Picasso to form their concepts of faceted patterns with monochromatic colors, the beginning of analytic Cubism. They continued to work together until 1914 and World War I when Braque joined the French Army. After he was wounded in the war, he continued to work and develop his styles of painting, sculptures, book illustrations, and lithographs.

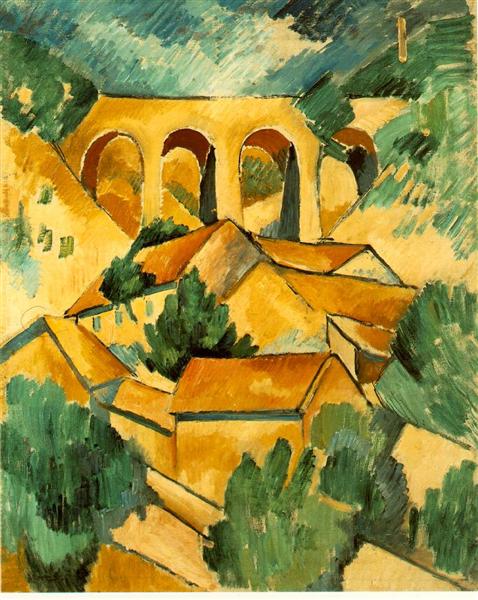

Braque painted The Viaduct at L’Estaque (5.4.6) when he was inspired by an exhibition of a painting from Cezanne of the region, a common location for Impressionist painters. Braque created the image of the viaduct and small town at the beginning of his Cubist work; the parts of the painting are beginning to be disassembled into shapes yet still retain the basic format. The buildings are simplified, fragmented, and flattened, eliminating the concept of depth and changing the rules of perspective into reconstructed forms. Braque exclaimed, “The hard-and-fast rules of perspective…were a ghastly mistake which…has taken four centuries to redress.”[3]

Violin and Candlestick (5.4.7) demonstrate Braque’s experiments to flatten space with a palette of browns and grays and narrow spacing. He used shading to give the perception that geometric shapes appear to overlay each other. He also incorporated curved lines in pure straight-lined geometrics. Cubists recurrently used musical instruments as part of their compositions, especially stringed instruments like guitars, violins, and clarinets. Braque was an accomplished musician and used instruments in much of his work. He placed the instruments through the center, highlighted by heavy dark lines and shadows, flattening the objects into multiple surfaces and different viewable planes. It appears the violin has been smashed into pieces while still intact, the pieces painted as the main violin.

Woman with a Guitar (5.4.8) was a later painting and based more on the synthetic style of Cubism. The image is abstracted and fractured, yet the basic form of the female’s eye and mouth are visible along with the trapezoid form of the guitar. He balances the image with dark shapes possibly identified as shoulders, framing the subject. Braque used color and shading to denote each element and shape to create harmony and move the viewer around the work with little difference between the subject and the background. The woman has multiple interpretations; she appears to look at the guitar and to the right. The muted color brings a somber mood, not any indication of frivolity, and heightens the concept of what the woman is thinking. The text was also a common component in a painting by both Braque and Picasso; sometimes, the words were part of the meaning of a painting and, at other times, superficially meaningless.

%252C_oil_and_charcoal_on_canvas%252C_130_%25C3%2597_73_cm%252C_Muse%25CC%2581e_National_d'Art_Moderne%252C_Centre_Pompidou.jpg?revision=1)

Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger (1881-1955) was born in France and, as a teenager, became an apprentice to an architect before starting as a draftsman and attending classes at an art academy. Early, he was influenced by Impressionism, followed by viewing the work of Cézanne. When he moved to Paris, he worked with other Cubist artists to develop a slightly different style the critics termed “Tubism.” Most of his geometric forms were based on cylindrical forms instead of rectangles, trapezoids, or squares. The abstracted forms usually contained primary colors; red, blue, yellow, black, gray, and white. During his life, he also developed artwork based on other movements with projects including ceramic sculptures, set and costume designs, and paintings.

Nude Model in the Studio (5.4.9) was completed while Picasso and Braque fully embraced analytic Cubism. Léger splintered the planes of his image to create three-dimensional objects with a more delineated form of larger parts, broad curving lines, and color. The curved and overlapped planes bring a rhythm to the painting and the concept of volume in the space. The standing female nude is positioned in a three-quarter profile, the right arm raised behind her head. He believed the human figure should be expressionless, unsentimental in his work.

%252C_oil_on_burlap%252C_128.6_x_95.9_cm%252C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Museum%252C_New_York%252C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim.jpg?revision=1)

Contrast of Forms (5.4.10) is a set Léger completed using cylindrical and cubic sections to form the planes with alternating places of voids and shapes while highlighting the interaction of light and shadows. He used color to enhance the format and dimension of the images and present the illusion of a three-dimension on two-dimensional canvas. White is applied roughly, and some of the canvas shows, aiding in the feel of dimension.

Juan Gris

Juan Gris (1887-1927) was born in Spain, where he studied art before moving to Paris. He married, and had one child and a secondary companion. At first, he worked as a satirical cartoonist before painting seriously, then exhibited with the other Cubist painters. At first, Gris painted in the analytical style before embracing the synthetic style of Cubism. He used heavy shapes with shading between the angles, obscuring the division between the subject and background with overlapping planes. For the Ballet Russes, he designed costumes and sets while continuing to paint. Unfortunately, he suffered from cardiac complications and died at the early age of forty.

The Harlequin was a familiar character in Italian comedies from the sixteenth century. He also wore the recognizable checkered costume as a character who established his talent as a charlatan. The Harlequin was a favorite form for the Cubist artists to include in their paintings, a theme especially favored by Gris, who incorporated the subject in almost forty of his paintings. In Harlequin with a Guitar (5.4.11), Gris used contrasting colors to define different elements, highlighted by patches and lines of black. The face is reduced and identified with small shapes as light appears to reflect off the illuminated areas.

Still, Life with Checkered Tablecloth (5.4.12) is almost a still life for men as the small table covered with the checkered cloth is brimming with a beer bottle, wine glasses, coffee cups, and wine bottles. The large fruit bowl holding grapes is viewed from above and on the side. The painting also portrays the paper ready for reading and the ubiquitous guitar. However, Gris added another image and dimension to the painting not as obvious; a bull’s head. Gris was from Spain, and the bull was an important cultural symbol. The nose of the bull is near the bottom and formed by the coffee cup, the one eye is a black and white circle on the left side, the bottle of beer is the ear, and the side of the guitar creates the horn. “The letters “EAU” on the wine label, which ostensibly stands for “bEAUjolais” can just as easily represent “taurEAU” (bull).”[4]

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_116.5_x_89.3_cm.jpg?revision=1)

Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) was born in Ukraine and sent to live with wealthy relatives in St. Petersburg, Russia, who traveled with her throughout Europe. In school, she was classically trained before moving to Paris. Her early work in France was influenced by the Post-Impressionists and the Fauvists and their uses of color. In 1908, she married an art gallery owner who helped her exhibit work and enters the art world while he could access her dowry and have a perfect cover for his homosexuality. At the gallery, she met Robert Delaunay, divorced her husband, and married Delaunay in 1910. She said, “In Robert Delaunay, I found a poet. A poet who wrote not with words but with colours.”[5] After their son was born, she transitioned from the concepts of perspective and the natural appearance to experimenting with Cubism and the intersection of color. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were influenced by Michel Eugéne Chevreuil’s concepts and his law of simultaneously contrasting colors. Both Delaunays, working with the theory, started painting with the overlapping planes and lines of Cubism combined through the concentration and vibrancy of color. A friend of the Delaunays described Cubism as Orphism, a more lyrical abstraction with bright and pure colors.

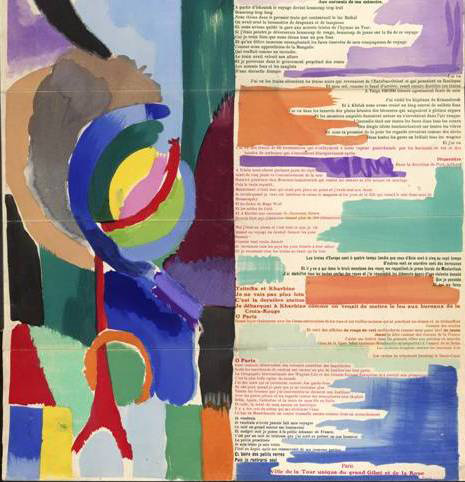

One of Delaunay’s first major projects was the illustration of the poem of Blaise Cendrars, who wrote Prose of the Trans-Siberian and Little Jehanne of France. The book was two meters long and formed into an accordion-pleated book. Delaunay combined her design with the text, as seen in the last section (5.4.13). The book and her illustrations were well received and helped establish her talents. After the Russian Revolution, she lost financial support from her family in Russia. She started designing costumes and sets for the theatre as well as a successful clothing business. Later in her life, she continued designing textiles, jewelry, clothing, and tableware until she died in 1979 at 94.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Transsiberien (1913, illustrated book with watercolor applied through pochoir and relief print on paper, 200 x 35.6 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Transsiberien (1913, illustrated book with watercolor applied through pochoir and relief print on paper, 200 x 35.6 cm) Public DomainPrismes Electriques (5.4.14) attract variations of light with color as the primary theme. The energy of the circular patterns moves throughout the painting as light is diffracted, bringing movement to the circles. The overlapping circles form curved spaces of primary colors and neighboring secondary colors. The rest of the painting has multiple geometric rectangular and oval planes. She was supposedly influenced by the glow of the electric streetlights and used Chevreuil’s concept of color to produce light; she combined lighter and darker colors to create a similar pattern.

Robert Delaunay

Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) was born in France and raised by his aunt and uncle. Because he wanted to be an artist, his uncle sent him to an art school in Paris and at 19 had accumulated enough work to exhibit in the Salon des Indépendants in 1904. He formed a close friendship with Jean Metzinger, and they both experimented with Cubism techniques. After he married his wife, Sonia, they worked together and developed Orphism using bright colors and shapes. He believed painting was a visual art based on how the eye perceives color and light plus their contrasting harmonies. In 1912, at the height of Cubism, Delaunay was accused of only making decorative paintings because of his use of color. After the war, he continued to work abstractly and did some Surrealism work.

One of his early series of works was the Windows series, abstract formats with overlapping planes of color. He visited the cathedrals and based the series on the observation of stained-glass windows defined by how the light shines through with patches of color and divergent hues. He wrote, “Direct observation of the luminous essence of nature is for me indispensable.”[6] Simultaneous Windows on the City Windows on the City (5.4.15) was part of the series with corresponding blocks of light and dark color, the colors slightly muted. He made the window illusion with the rectangular black line, the light, and colors escaping around the window and into space.

%252C_40_x_46_cm%252C_Kunsthalle_Hamburg.jpg?revision=1)

Hommage to Biériot (5.4.16) was dedicated to Louis Biériot, the first person to successfully fly an airplane between England and continental Europe. The disassembled images on the painting portray the helicopter, and the human with the Eiffel Tower was added to honor Bériot as a French man. Delanuany’s use of Orphism is apparent in the use of primary colors, the bright red punches of color, and the seemingly joyous spirit of the concentric disks spanning in waves across the painting.

Jean Metzinger

Jean Metzinger (1883-1956) was descended from a well-known French military family. Although his mother wanted him to become a doctor, he studied art, exhibiting at the early Salon shows with the Fauvists and then the Cubists. Metzinger originally painted in the style of the Impressionists and Pointillism with significant mosaic-like brush marks, focusing on the use and juxtaposition of colors. He frequently painted with Robert Delaunay, experimenting with new styles, especially fracturing the human form to create compound views of the same image. By 1910, he began to paint in the Analytical Cubism style, working with Delaunay, Léger, and Laurencin. In 1911, they all hung their work together in Room 41 of the Salon des Indépendants; the exhibit was deemed scandalous. Metzinger is credited with writing the first major dissertation on the new art form, Du “Cubisme,” presenting information about Cubism, understanding the works and why they are created in the specific dimensions. The publication was very successful, and Metzinger was credited as one of the leading artists of the new concepts. Apollinaire, a poet of the time who viewed Metzinger’s work, wrote, “Graphically and compositionally, his works have all the discretion of contrasting luminosity, and a style which places them apart from, and perhaps well above, most works produced by the painters of his day.”[7]

Two Nudes, Two Women (5.4.17) was part of Metzinger’s association with the Analytic Cubism style. Instead of positioning the two nudes in the foreground as the traditional practice, he integrated them with the background of trees and rocks. The models are visible from multiple viewpoints, shattered into angles and shapes, bringing different spatial projections. The interlocking of spaces and shapes of the figures and background create a total environment, a three-dimensional perspective on a two-dimensional canvas. Although Metzinger muted his colors, he did include other colors in his palette, unlike Braque and Picasso. This painting was part of the Salon des Indépendants, the scandalous show, and the rise of Cubism.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_92_x_66_cm%252C_Gothenburg_Museum_of_Art%252C_Sweden.jpg?revision=1)

L’Oiseau Bleu (The Blue Bird) (5.4.18) is one of Metzinger’s most well-known works and part of his association with Braque and Picasso and the Cubist movement. The painting depicts three nude women surrounded by a variety of other elements. In the center, one figure is holding a bluebird, the reclining woman on the left is seated by a red bird and a fruit bowl, and the figure on the right is holding a yellow fan. Other birds, a steamship, and a small boat float through the scene. The striped canopy representing a Parisian cafe is left intact, not fractured. Unlike the other Cubism artists, Metzinger used a very colorful palette; however, he muted the colors similar to the other artists.

_oil_on_canvas%252C_230_x_196_cm%252C_Muse%25CC%2581e_d'Art_Moderne_de_la_Ville_de_Paris..jpg?revision=1)

Marie Laurencin

Marie Laurencin (1883-1956) was born in Paris and originally studied ceramics before changing to oil painting. She was romantically linked to poet Guillaume Apollinaire, associated with Metzinger, Braque and Delaunay and exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in concert with the Cubists. She married a German, causing her to lose her French citizenship, a woman had to take her husband’s citizenship. During World War I, the two had to flee to Germany; however, she divorced him and returned to Paris after the war. Upon returning, she adopted her new style, painting the thin, willowy, otherworldly female figures with simplified volumes and curvilinear in muted pastel colors focusing on grays and pinks. She also painted portraits, and defined theatre and ballet sets, watercolors, and prints.

Jeune Femmes (Young Girls) (5.4.19) was one of Laurencin’s first paintings exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911. Her curvilinear lines simplified the geometric shapes, giving the painting graceful lines. She used the darker, muted tones found in early Cubism painting with a small amount of color.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_115_x_146_cm%252C_Moderna_Museet%252C_Stockholm.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=1045&height=806)

Le Bal Elegant, La Danse a la Campagne ( Elegant Ball, Dance in the Country) (5.4.20) was painted a few years later, and Laurencin used her traditional lighter and more feminine palette with muted pinks and grays. The shapes are also more fragmented, following the style of Braque and Picasso. The figures have soft edges as the background shapes and lines became straighter and more fractured.

Les Désguisés (5.4.21) depicts two figures dressed in elegant apparel who appear almost ghostly. The stylized images are rendered in muted colors; the wistful duo adorned with flowing headdresses. She also added a bird on the head of the seated woman and a bouquet. Laurencin painted the images after she returned to Paris from Germany, as new avant-garde ideas were beginning. She still used flat planes of pastel colors giving the painting a look similar to the earlier Cubist works.

Most historians believe Cubism, in a short time, was the one movement to create and produce an entirely new style and form of art, transforming and influencing the future direction of new movements. The artists were dissatisfied to follow the orthodox rules of painting in the three-dimensional ideals; instead, they wanted to include multiple sensations, a total image on a flat surface. The creative and innovative artists of the movement also continued to experiment and develop new directions.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/pablo-picasso-les-demoiselles-davignon-paris-june-july-1907/

[2] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/pablo-picasso-les-demoiselles-davignon-paris-june-july-1907/

[3] Retrieved from http://www.georgesbraque.net/viaduct-at-l-estaque/

[4] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/646469

[5] Baron, S., Damase, J. (1995). Sonia Delaunay: The Life of an Artist, Harry N. Abrams, p. 20.

[6] Retrieved from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/simultanism

[7] Apollinaire, G. (1913). The Cubist Painters, translated, with commentary by Peter Read, University of California Press, 2004, p.43.