3.3: Fauvism (1905-1910)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 174413

Introduction

During the early part of the twentieth century, Fauvism started in France, disregarding the methods of the Impressionists to bring vivid, bold colors from the tube to the canvas. They were introduced by Henri Matisse and Andre Derain when they were experimenting with color to create movement with colorful sensations. Some of the work was similar to the Expressionists; however, the Fauvists focused on the organization of the image while the Expressions concentrated on emotions. At their first exhibit at the Salon d'Automne in 1905, one critic declared, "A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public."[1] The artists' intense colors to portray emotions, and their aggressive brushstrokes with enthusiastic loose globs of paint, added a decorative effect to their work. They were interested in complementary colors and how they appeared side by side. Fauvism was frequently thought of as an extension of the previous Post-Impressionism. As a group, they had little else in common except color, each painting a different subject matter. Most of them moved on to other styles later in their life. The movement only lasted about ten years, and they held three exhibitions; however, the style was still represented in other works by the artists.

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was born in France to wealthy parents, studied law, and worked a few years in the courts. He decided to study art and went to Paris to learn from the masters he copied in the Louvre. After a friend introduced Matisse to the Impressionists' work, he became inspired by color and redefined how color could express emotions. Although the period of Fauvism was short, Matisse established his reputation as an artist of explosive and expressive color, at first condemned and later famous. When the Nazis invaded France, they started to attack the degenerate art as they did earlier in Germany. Matisse and other artists were allowed to exhibit as long as they attested to their 'Aryan' status; all Jewish artists were purged.

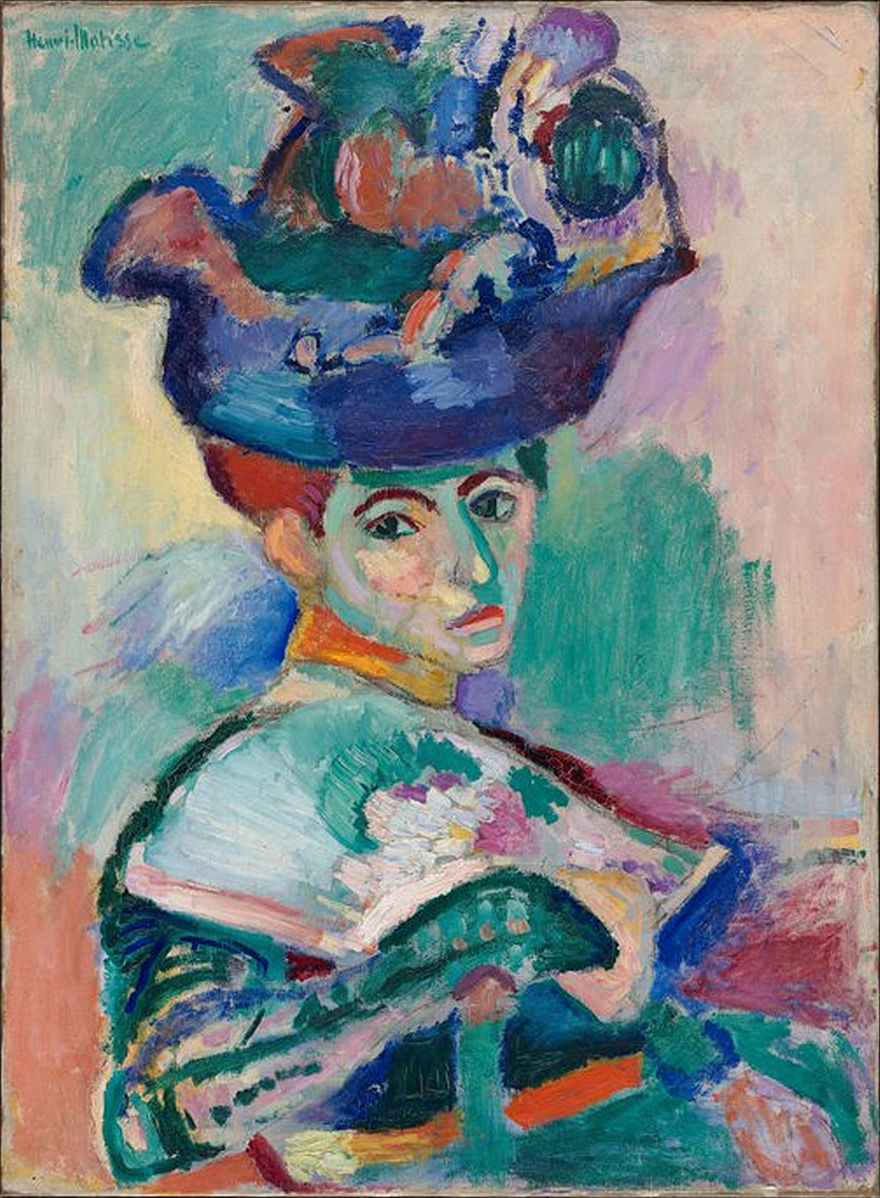

Woman with a Hat (5.3.1), a departure from his earlier more realistic style, Matisse was displayed at the first exhibition the group of Fauvist artists held. The painting caused great controversy and was said to be scandalous. Matisse used a looser brushstroke and colors considered unnatural; the painting was called unfinished. The wife of Matisse posed for the painting, holding a fan in her hand, her head turned in a pose used by the bourgeoisie, an oversized hat on her head. When Matisse was asked what kind of dress his wife was wearing, he replied, "Black, obviously."[2] Critics and viewers have always questioned the meaning of the colors. Do colors refer to anything, in reality, a tribute to the jarring effect of Matisse.

Matisse received a commission from a Russian industrialist for three oversized paintings to adorn the wall of a Moscow palace. He considered La Danse (first version) (5.3.2) an initial painting. The dancers are loosely drawn, seemingly unrestrained, perhaps expressing their joy. Matisse painted depth into the flat canvas, using the blue against the green; does the blue represent the sky, or are they, dancers, by a lake. The hands of the two dancers in front are parted; why did he leave the slight distance.

_by_Matisse.jpg?revision=1)

La Danse (second version) (5.3.3) looks quite different as he changed the colors and emotions. The figures are more defined, and muscular, presenting tension with the dancers. In the first version, the back figures seem to lightly touch the green and, in the second version, the rear figures compress the green, appearing to stomp instead of float, anger instead of joy. Both images relied on his use of color to display the movement and emotions of the dancers. These paintings depict his use of ambiguity and suggestions, undefined and open to the viewer.

Matisse frequently used his images of the dancers in other paintings when he painted his studio. In Still Life with Dance (5.3.4), the painting of La Danse is sitting on an easel in the background. He moved a table, turning it, so the corner created depth by jutting into the back of the painting. The table was set with random and loosely grouped still life items, including the ubiquitous sunflowers, and a tray of fruit with fruit also painted on the table. Matisse included the window for added depth as the painting is in front of the darkened window.

Nasturtiums with the Painting La Danse (5.3.5) presented another more intimate part of his studio. Only one side of the image of La Danse is seen; a vase of nasturtiums sits in front of the painting. The back leg of the tripod-shaped table appears to be part of the painting itself, the leg resting on the green, behind the purple stripe with the two front legs on the floor. The top part of the chair extends the purple line across the entire painting. In this painting, Matisse used the darker background and figures of the second dance painting.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_193_x_114_cm%252C_Pushkin_Museum.jpg?revision=1)

Émilie Charmy

Émilie Charmy (1878-1974) was born in France, becoming an orphan as a teenager. While living with relatives in Lyon, she was trained as a teacher, the acceptable occupation for a woman. However, she was obsessed with art, studied with other artists, and started painting to support herself, painting common views of women in domestic settings or still-life. These images sold well and left her unsatisfied.

In 1903, she moved to Paris, where she became part of the Fauve artists headed by Matisse. Like the others, she experimented with new methods of applying thick paint with crude, heavy brushstrokes. Although she was associated with the artists in exhibitions, her work was hung separately, receiving little attention as a female painter. Because of her bold use of color, one of the French novelists stated, "Émilie Charmy, it would appear, sees like a woman and paints like a man; from the one she takes grace and from the other strength, and this is what makes her such a strange and powerful painter who holds our attention." [3]

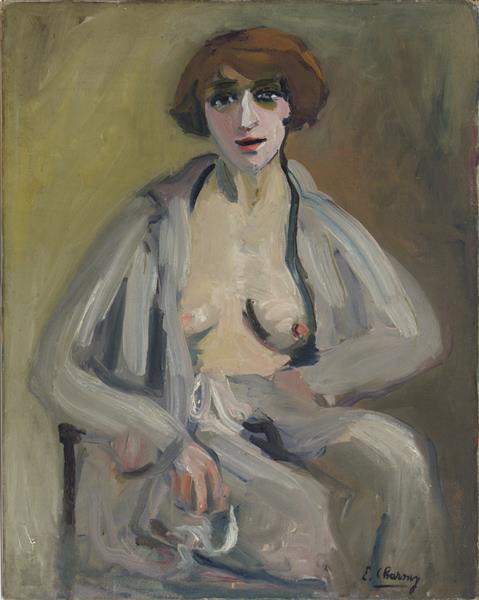

During this time, gender roles were well defined, and women did not paint from nude models, only encouraged to paint the traditional roles of women and children. However, Charmy did not follow the trend and instead used female models she posed in simple settings, applying her unique brushwork and color and sparking much controversy in her early shows. When she was unable to find a suitable model, she used it herself. Self-Portrait in an Open Dressing Gown (5.3.6) shows her sitting casually against the dark background. Her robe and skin are painted with muted colors applied with broad brushstrokes of thick paint.

Self-Portrait with an Album (5.3.7) is painted with a small palette of colors; however, the dark colors are contrasted; black against red with the bright, pale skin color. She presents two different looks in the paintings; one has a reticent look on her face, while the other displays more confidence. Charmy's thick, fast brushstrokes sometimes appear crude; however, her brushwork brings a unique visceral quality to her paintings.

Georges Rouault

Georges Rouault (1871-1958), born in Paris, was fortunate to have a mother who loved the arts and, despite her poverty, encouraged her soon to pursue art. At first, he was a stained-glass painter, and historians believe it formed his interest in using heavy black lines in his paintings. Rouault also studied art, meeting Matisse and the others whose friendships led to Fauvism. He focused his work on images based on people in the circus or prostitutes during this early time in his life. Many believed in moral criticism because of his devotion to religion. His later paintings were generally based on religious themes. Rouault used intense colors, predominantly blues in watercolor and gouache, adding scrawling lines throughout the images.

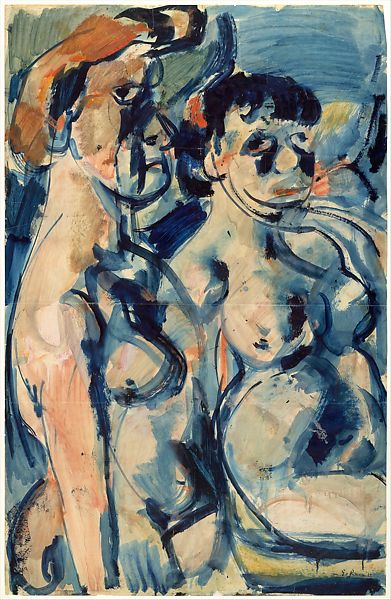

Two Nudes (5.3.8), images of two prostitutes, was a subject he used to depict the vices of society. The heavy dark outlines seeped through the paper, creating an image on both sides of the paper. He used diluted oils almost the consistency of watercolor, coloring the image on the other side, the figures in reverse, and signing both sides of the paper.

For Three Nudes (5.3.9), he used watercolor and oil on paper. The heavy lines break up the images painted in grays, unusual for Rouault, demonstrating his gestures and distorting space and shapes.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Three Nudes (1907, watercolor on oil on paper, mounted to canvas, 100 x 64.8) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Three Nudes (1907, watercolor on oil on paper, mounted to canvas, 100 x 64.8) Public DomainCircus Girl (5.3.10) reflected the small circuses that traveled throughout Europe at the time; the girl playing her part resigned to her role. Although Rouault uses blocks of color to express emotions, his palette was muted compared to the rest of the Fauvists. Dark, heavy lines form the woman's torso; the colors are a shadowy reminiscence from the inside of the church through the colors of the glass.

Andre Derain

Andre Derain (1880-1954) was born outside of Paris and studied art at an early age while also attending school to learn engineering. He met Matisse and painted with him in the small town of Collioure, displaying their work together in the Salon de'Automne. Derain went to England and painted several images of London using bold colors and unusual forms, all quite different from other paintings of London.

Not since Monet has anyone made London seem so fresh and yet remain quintessentially English. Some of his views of the Thames use the Pointillist technique of multiple dots, although by this time, because the dots have become much larger, it is rather more simply the separation of colours called Divisionism and it is peculiarly effective in conveying the fragmentation of colour in moving water in sunlight.[4]

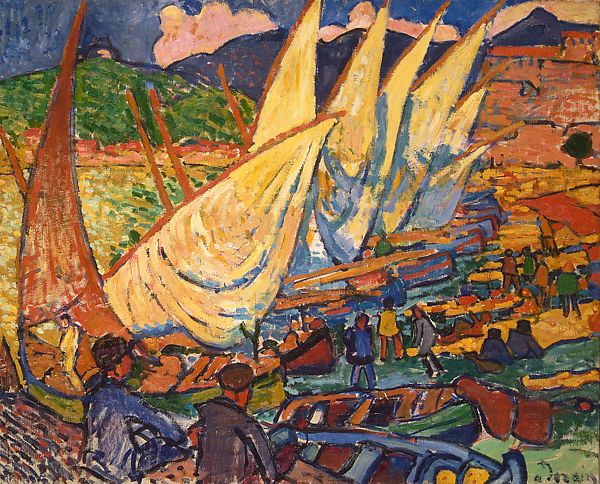

Derain was only twenty-five when he went to Collioure with Matisse to paint the local scenes. Fishing Boats (5.3.11) demonstrates how Derain used diagonals to create perspective. The tilted and overlapping sails billow along the curved shore, the two men seated in front watching the activities of the busy figures. He used heavy lines, especially in the foreground, and filled the painting with bold colors.

When Derain went to London in 1906, he filled sketchbooks with scenes and images of the London streets, creating the paintings when he returned to his studio in Paris. Regent Street, London (5.3.12) displays bold colors in some areas and a more subdued palette of blues in the background. He drew heavy lines delineating the figures and animals, seemingly jamming the streets with movement from a vibrant city with a large population of almost 400,000 people.

Maurice de Vlaminck

Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) was born in Paris; his parents were both musicians. He studied art as a teen, then served in the military, and when he was coming home on the train, met Andre Derain, a fellow painter he remained friends with for life. Vlaminck, Derain, and Matisse started the group and exhibits of the Fauvists. Most of his paintings were landscapes, the places he saw in France, at first using the bright colors and ideas of the Fauvists, later adopting a more muted palette.

Vlaminck shared a studio with Derain in the small village of Chatou by the Seine River, a place he found many images to paint. The Seine by the Chatou (5.3.13) is painted from a small island looking back at the mainland. Vlaminck admired van Gogh and used a similar brushstroke to apply the paint from the tubes, daub it onto the canvas and swirl the brush through the bright, primary colors. He bent the tree trunks, curving in contrast to the straight mast of the boat.

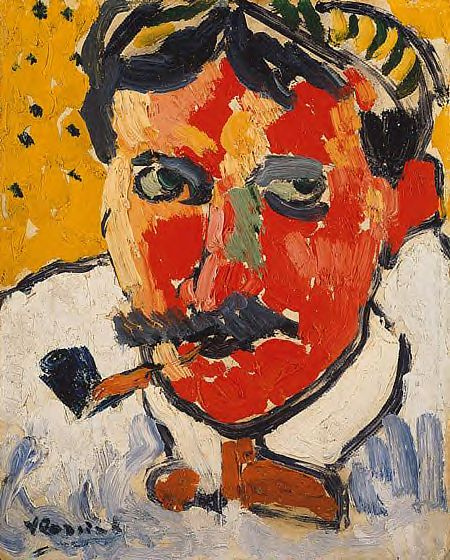

Vlaminck painted his associate Andre Derain (5.3.14) almost life-sized in an unusually close view. The head is outlined in dark, weighty lines. He used extreme versions of the primary colors on the face, primarily red with yellow shading and blue eyelids, and the green blotch on his nose. The mustache is asymmetrical and twists out past the face onto the shirt. The head seems to float in the middle of the painting as the white shirt is higher in the back.

Nadežda Petrovic

Nadežda Petrovic (1873-1915) was born in Serbia and graduated from the women's school of education. She taught art there and at the university in Belgrade before going to Germany for further study. Petrovic was successful and exhibited her work in multiple European shows. While she worked as an artist and art teacher, she also volunteered for different human rights organizations. During the Balkan Wars in 1912, Petrovic worked as a nurse and was awarded for her courage by the Serbian government. However, while Petrovic worked in the field, she became ill with both typhus and cholera, surviving both diseases. After the war, Petrovic continued painting until the Austria-Hungary war in 1914. Again, she went to volunteer as a nurse. Unfortunately, this time she died of typhoid fever in the Serbian hospital where she cared for wounded soldiers.

Petrovic painted portraits; however, her primary focus was landscaped, particularly those representing the history and views of Serbia. She used strong, bold brushstrokes in thick layers of paint on the canvas creating vortexes of color. Red was generally the focal color with purple and black shadows. Resnick (5.3.15) was a local village she portrayed through its winding road starting at the edge of the painting, trees, and wooden fences adjoining the road. Some of the paint was applied with thick, pasty strokes, and others by colors of thin glazes. Petrovic used a varied palette to express the character and feeling of her village and the rhythm of the road.

Ksenija Atanasijevic (5.3.16) was one of the first females to become a professor at Belgrade University and the first to receive a Ph.D. in Philosophy. She became a noted Serbian philosopher and a friend of Petrovic, who painted her portrait. Petrovic used her unique brushstrokes, vertical gray in the background and diagonal lines in the sky and foreground snow. Atanasijevic, who was sixteen, is wearing an oversized black hat she recently purchased in Paris. Her black clothing and determined look foretell the successful future of the young woman.

Kees van Dongen

Kees van Dongen (1877-1968) was born in the Netherlands, studying art at the Academy of Arts in Rotterdam. He left for Paris in 1899, where he married and had two children. As a poor artist with a vegetarian wife, the family usually survived on spinach. Gertrude Stein wrote, "Van Dongen frequently escaped from the spinach to a joint in Montmartre where the girls paid for his dinner and his drinks."[5] He became friends with the other artists who had studios in Montmartre, including Matisse and Derain, exhibiting his work at the 1905 Salon d'Automne show, displaying their bright use of color. He had an endless supply of models from the cabaret dancers and performers who modeled during the day, flamboyant figures for his improvised, almost garish use of color. After World War I, he was a popular artist and in-demand to paint portraits of the elite class. He specialized in painting women with an elongated and slimmer shape, enlarged jewelry, and oversized expressive eyes.

The nudes van Dongen painted in Paris as part of the Fauve exhibition were rated as scandalous by the critics who were also attracted to their melancholy beauty, causing conflicting reviews. The Femme au Grand Chapeau (5.3.17), a woman who wore little more than the elegant, theatrical-like hat, was based on the model Fernand Olivier who was also Picasso's model and mistress. Van Dongen was fascinated by the bright colors of the Fauvists and the flamboyant lifestyle of Parisian dancers and performers. In the painting, he used greens and yellows to create almost florescent skin tones highlighted by his signature oversized eyes and lips, giving her an appearance of defiance.

In the cabarets in Paris, wrestling exhibitions based on rigged matches attracted viewers to the cabarets. Although wrestling was the sport of the "strong man," the concept became outmoded when the sport turned into a spectacle. Without the need for strength, women's wrestling and carefully orchestrated matches became popular. Women and men equally displayed notions of physicality. However, "through the neutralization of gender, a woman could challenge a man as 'an equal' and experience a certain leeway in the exhibition of her body, almost to the point of eroticism."[6] Van Dongen had a studio in Montmartre near Picasso and frequently used Picasso's mistress and a model. When he saw the five females in Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, he painted twice as many in his painting Tabarin Wrestlers 5.3.18). Van Dongen portrayed the strength of the female wrestlers overlaid with eroticism; they appear nude yet dressed in skin tone body suits based on the straps on the top of the suit. He used the same hues throughout the painting, changing from light to dark to create depth.

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_105.5_x_164_cm%252C_Nouveau_Muse%25CC%2581e_National_de_Monaco.jpg?revision=1)

Europe was now industrialized, populations were expanding, and a rising nationalism was permeating throughout the region, challenging the old-world standards and intellectual beliefs. The changes also crossed into the world of art as artists began to experiment with color and line, altering the view and ideals of the human figure, and squeezing the paint from tubes onto their brushes. The color was based on the artist's feelings, not remarkably realistic; expression was applied with spacious brushstrokes.

[1] Chilvers, I., (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, p. 250.

[2] Retrieved from https://www.lrb.co.uk/v30/n16/tj-clark/madame-matisses-hat

[3] Perry, G. (1995). Women Artists and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Manchester University Press, p. 100. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89milie_Charmy

[4] Rosenthal, T., Reviewing Derain’s London paintings on show at the Courtauld Gallery, The Independent, 4 December 2005. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9_Derain

[5] Stein, G. (1990). Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein, Vintage, p. 26.

[6] Horton, A. (2018). Identity in Professional Wrestling: Essays on Nationality, Race and Gender, McFarland, p. 208.