9.4: Modern Sculpture (1970 – 2000)

- Page ID

- 209047

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction

By the 1960s, the concept of sculptures was changed, and the trend towards abstract and figurative firmly in place as traditional ideas were rejected. New materials were available, and sculptors began experimenting with them, bringing more sophistication to create and manufacture sculptures and huge images. Sculptors no longer created a single figure out of marble or bronze; using multiple materials involved additional people beyond the artist. Projects, particularly outdoors, became collaborative efforts with landscape designers and site architects. Site-specific and environmental works on a grand scale were pioneered during this period. The landscape was the basis of sculpture for some artists, and works were integrated into existing environments.

During the modern sculpture period, the decision regarding the materials used by artists was of utmost importance, as it relied upon the technology available at the time and the environment where their work was to be displayed. Sculptors who employed metal in their creations necessitated a significant amount of space and advanced technology to cast or weld their pieces. Those who worked extensively in factories required trucks and oversized cranes to transport and install their art. In contrast, some artists opted to source materials from the natural environment, which they then used to create their work. Others combined natural elements with artificial materials to produce stunning, unique pieces. Some artwork was intended to be permanently installed, while others were created to be temporary and responsive to natural forces. Artists in this section:

- Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012)

- Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017)

- Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010)

- Viola Frey (1933-2004)

- Liliane Lijn's (1939-)

- Lynda Benglis (1941-)

Elizabeth Catlett

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) was born in Washington, D.C., and lived there as a child. Her grandparents were formerly enslaved people and often told Catlett stories about Africa and the hardships of slavery. She graduated from Howard University with outstanding grades; however, Howard was not her first choice. Her original admission into the Carnegie Institute of Technology was overturned when the university discovered Catlett was black. Although she was always interested in art, the concept of a black woman as an artist was unacceptable, and Catlett majored in education. She admired the work of Grant Wood and decided to attend the University of Iowa's graduate program, where Wood was a teacher. She was accepted into the university but could not reside in the dormitories and had to rent a room in town. Catlett earned a Master of Fine Arts at the university. She spent time in Mexico studying sculpture and was active in social politics. Because of Catlett's activism, she was barred from returning to the United States; instead, she became a citizen of Mexico.

Throughout her career, Catlett consistently worked making prints while shifting to her central art of sculptures. She used multiple types of material for her sculptures in various sizes and themes, famous to ordinary people. Her major works were about black women whom she depicts as strong and caring with their torsos slanted forward to demonstrate attitude. Pensive Figure (9.4.1) portrays a sculpture of an abstracted woman sitting thoughtfully, gazing into the distance. Viewers might feel they had to walk quietly while looking at the bronze statue, unwilling to interrupt the woman's thoughts. Her clothing style is unknown until the bottom half of the figure, and it appears she wears a dress based on the line above her crossed legs. El Abrazo (The Embrace) (9.4.2) demonstrates Catlett's exceptional use of wood. The work is carved from a single piece of wood, and she used the grain of the mahogany to accentuate the entwined bodies. The pair's faces look outward at the viewer, not at each other. Their direct gaze lets the viewer share their humanity. Catlett stated, "I still work figuratively, trying to express emotion through abstract form, color, line, and space…Even in more abstract sculpture, I attempt to get a reaction, possibly by a strong upward gesture or a close tight feeling between two figures."[1]

2017 Art on Campus - "Totem" by Elizabeth Catlett

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017) was born in Poland; her mother descended from the previous Polish nobility. The family had fled an earlier Russian invasion of the Polish countryside, and they moved to the city. Abakanowicz was only nine when the Nazis invaded Poland. During the war and occupation years, the family lived outside Warsaw and was part of the resistance. After the war, the Soviet Union controlled Poland, and the Soviets defined art as Socialist Realism, the only acceptable art for artists. Anything modern or style influenced by Western art was outlawed, and the government completely censored art. Abakanowicz attended different art schools and was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1950-54. The laws of Socialist Realism forced strict rules for the students to follow, and realist portrayals of traditional 19th-century images became the only thing taught at the university. Abakanowicz believed the Academy was rigid and challenging to learn and said, "I liked to draw, seeking the form by placing lines, one next to the other. The professor would come with an eraser in his hand and rub out every unnecessary line on my drawing, leaving a thin, dry contour. I hated him for it."[2] Abakanowicz did take many textile design classes; the methods she learned later influenced her work.

When Abakanowicz started working as an artist in Poland, the Soviet-controlled country was relatively poor, and artists had little access to materials. She gathered any pieces of materials she found and kept them stored under the bed for possible use. Embryology (9.4.3) was made from rough-hewn fabrics she stuffed. She created a series of different installations using fabric because she liked the concept of no tool between her hands and the material. Her hands were the energy creating the sculpture. The objects in this installation are strewn with no order creating a disturbing scene, appearing as bodies of some sort. Each element seems heavy, like a dead weight from afar. Closer inspection reveals fabric with seams and stuffing, soft to the touch. Because of the brutality of the war and the harshness of Soviet control, many wondered if the stacked figures were a sign of Auschwitz. The human figure was an essential part of Abakanowicz's work, whether overt or implied. Throughout her sculptures, she used different materials in a diversity of forms. However, she always returned to the concept of the fragility of humans. Space of Human Growth (9.4.4) covers 2,012 square meters. The oversized concrete shapes are undefined; the meaning is left to the viewer. Abakanowicz always abstracted her forms, living things, ambiguous and open to the viewer's interpretation. Installed in a park in Lithuania were the objects, unopened blossoms, parts of the human body, or maybe even haystacks, open for viewer interpretation.

Bronze Crowd (9.4.5) is a set of bronze abstracted figures standing emotionless. Abakanowicz based her work on references to the turmoil of her past, war, and brutal Soviet occupation. She said, "It happened to me to live in times which were extraordinary by their various forms of collective hate and collective adulation. Marches and parades worshipped leaders, great and good, who soon became mass murderers. I was obsessed with the image of the crowd, manipulated like a brainless organism and acting like a brainless organism. I suspected that under the human skull, instincts and emotions overpower the intellect without us being aware of it."[3] The statues in this installation are devoid of any hint of feeling or thought, just the lineup of humans dutifully standing in a row. Even their clothing is wrapped tightly around their bodies, removing all freedom of movement as the leaders control them. The control of art education by the academy Abakanowicz attended is evident in her artwork as she consistently moves beyond the insistence of realism into the consistency of abstraction. Ten Seated Figures (9.4.6) appear the same, all sitting in a row, legs down, backs straight. A closer look reveals the individuality of each one as the protective patina is applied differently, and the surfaces are wrinkled and textured. The figures are headless; perhaps they do not need brains to think when leaders rigidly control them.

Find out how an artist affected by World War II created work encouraging us to stand up for others. Magdalena Abakanowicz, Bronze Crowd, 1990-91.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) was born in Paris, France. Her parents originally had a gallery selling antique tapestries. When Bourgeois was still small, her parent started repairing antique rugs, filling in tattered areas. Bourgeois received a good education in design and color. In 1930, she went to the Sorbonne to major in mathematics. However, when her mother died while Bourgeois was in school, Bourgeois switched to studying art. After graduating from Sorbonne, she also studied art at some Academies. When she married, they moved to New York City. In the 1940s, she made sculptures from wood and other materials like plaster and latex. During the 1950s and 1960s, Bourgeois was severely depressed and spent significant time in psychoanalysis. By the 1970s and 1980s, she started working in bronze and making large-scale works.

Louise Bourgeois, a renowned artist, is widely recognized for her sculpture Maman (9.4.7), which is a larger-than-life bronze creature that creates a sense of terror in one's imagination. The sculpture features a spider that holds her eggs in a sac section of her body, and she stands tall with overly long, spindly legs. The sculpture is elevated above a platform, and observers can walk underneath the legs and gaze up at the meshed sac holding the marble eggs. Bourgeois, who had experienced emotional abuse as a child from her father, found solace in her mother's support. She viewed the spider as a patient, methodical, and valuable creature that reminded her of her mother. Bourgeois created numerous spider sculptures of varying sizes, including The Nest (9.4.8), which features five different spiders standing atop one another. Each spider boasts its unique body structure and long knobby legs, which adds to the intricate details of the artwork. The spider sculptures by Bourgeois showcase her fascination with the arachnid's form and its symbolic representation of a mother's patience and care.

Located in a sculpture park in Oslo, Norway, "Eyes" (9.4.9) showcases two giant granite orbs overlooking the water. The distinctly tiny pupils give the impression of a gaze toward the scenery. While some visitors perceive the sculptures as massive eyes, others interpret them as a pair of breasts. The artist, Bourgeois, deliberately placed the structures on a small hill, inviting viewers to form their interpretations. Are they intended to represent eyes, or do they reflect an objectification of the female form from a male perspective? Eye Benches IV (9.4.10) are located in a park in New Orleans. These unique benches are bronze and feature eye-shaped designs with actual lights placed at the center. Sadly, Hurricane Katrina destroyed the square where the benches were installed initially. However, they were later reinstalled after the square was rebuilt. Bourgeois created several eye benches styles using bronze and granite materials. As people walk by, these eye benches sit in their designated spots, with their gaze fixed on the passersby while attracting viewers to look back at them.

Selvaag Art Collection - Louise Bourgeois

Viola Frey

Viola Frey (1933-2004) was born in California and received her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the California College of Arts and Crafts. Other students included Richard Diebenkorn, Manuel Neri, ad Nathan Oliveira, all active in the Bay Area Figurative movement. Frey went to New York to study at the Clay Art Center, where artists can investigate using ceramics beyond the usual constraints. She returned to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1960 and became one of the most respected ceramic artists. Her ceramics were based on enormous figures made from clay and painted with bright colors. Some figures were almost 3.5 meters high; their immensity required her to create the entire sculpture starting at ground level and building up the figure. After completing the details, the figure was cut apart to be fired and reassembled like a jigsaw puzzle. Frey frequently portrayed the men in suits and ties and her female figures either nude or in patterned 1950s-styled dresses. Although her specialty was immense ceramic figures, Frey also created paintings, drawings, photography, and work in glass. Her favorite art forms were miniature figurines she collected at flea markets. Frey took many of the smaller pieces and created assemblages of the parts. From the assembled components, she made molds to cast her sculptures made from amalgamated pieces,

Man Kicking the World (9.4.11) is dressed in a conventional suit of blues. Frey used red on his tie and face to dominate the otherwise bland person. He is looking at the world with his foot, ready to push the big world, only sensing some hesitancy about what might happen. She generally had men wear blue suits, portraying them as respectable and a symbol of power. The men were often seated or perhaps falling to demonstrate their vulnerabilities. As seen in Homage, Frey did a small number of nude men and depicted them as vulnerable figures (9.4.12). She started the series in the 1980s when the Aids epidemic was rampant, and her assistant lost his life to Aids. Frey commented on her nude males, "I think I saw them as figures of vulnerability. How vulnerable people are—especially the men, who were on such a crest in the sixties. Come crashing down to all of this. It doesn't seem quite right."[4] Frey treated the surface differently by covering the body in gashing white and orange intersected by yellows and blues. Her unusual use of color demonstrated her deep feelings about the subject.

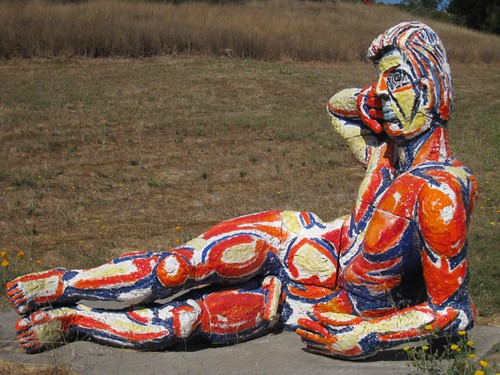

The artwork Woman with Elbow on Raised Knee (9.4.13) is a striking depiction of a woman exuding confidence and relaxation in her posture. The artist, Frey, was known for her tendency to portray women in a manner that exudes control and alertness towards their surroundings. In this particular piece, she utilized the color blue to define the shadow and the connections, adding a unique and intriguing touch to the artwork. Despite the woman's nudity, we cannot help but notice her well-groomed appearance, red nail polish, and lipstick perfectly in place, and neatly combed hair. It is clear that Frey aimed to convey an average look and feel for both men and women, regardless of their size or position, making this artwork a testament to her artistic vision and prowess.

Remembering sculptor Viola Frey and her dedication to creating monumental ceramic figures.

Liliane Lijns

Liliane Lijn's (1939-) mother came to New York City from Belgium, and Lijn was born four months later. They were European Jews who were escaping the beginning of the wars. When she was fourteen and Europe recovered from the war, the family moved to Switzerland. Lijn studied archaeology and art history in Paris, hanging out in cafes and discussing poetry when she started to draw. She was always interested in different materials and experimented with plastics and how they reflected light or moved. Her first idea was the Poem Machine, where she combined her love of poetry and experimental sculptures—the words in the sculpture (9.4.14) spin, blurring, and vibrating. Lijn believed the power of words was diminished, and she wanted to change the visual expression of poetry into sound. She wanted people to see the sound. While she was in Paris, Lijn also noted the lack of women artists and started making forms resembling the power of females. Much of her early work was based on kinetic art, and she wanted to do more than make something move as she was very interested in the combination of art and science.

Armoured Head (9.4.15) is a small sculpture Lijn made with wire mesh formed to surround a sphere. The wire becomes looser as it progresses upward, leaving a large opening at the top. In the center, the sphere is zinc-blown glass with vertical lines. She made a series of different glass heads using the blow torch to create wounds on the head. Blowing glass was natural for Lijn as she used the scientific tools on her sculptures to display pain and suffering. Part of her investigation of glass was how light and the color spectrum reflected and changed the glass. Extrapolation (9.4.16) was a sculpture Lijn created based on the concepts of a book and the layers of pages in a book, a continuation of her interest in words. Spaces held apart the sculpture's layers of plates to allow light to flow through and a feeling of openness. When the light shines on the panels (9.4.17), they reflect the sky, appearing as one piece.

Meet Liliane Lijn, the American artist who pioneered the use of technology to make moving art.

Lynda Benglis

Lynda Benglis (1941-) was from Louisiana, a descendant of immigrants from Greece, and frequently went to visit Greece during her childhood. Benglis received her BFA at Newcomb College in Louisiana and studied art at Tulane University. In 1964, she moved to New York and worked with some of the significant artists during the period. In New York, she trained as an Abstract Expressionist. Benglis also studied at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, where she met Gordon Hart. In a short marriage, she married Hart so he could avoid the military draft. She lived in multiple places, including Greece, India, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Benglis started experimenting with more fluid substances and how a compliant material created its form. She called her new work 'pours.' After viewing Jackson Pollock's dripping method, Benglis poured liquid rubber onto the floor, the swirls of color appearing in motion and creating floor paintings. Benglis experimented with latex or melted beeswax onto boards. Later, she built up layers of fabric on the armature and poured the colored, melted material to create abstract sculptures. Benglis said, "I wasn't breaking away from painting but trying to redefine what it was."[5]

Benglis started to make the prehistoric-looking creatures of North South East West (9.4.18) by forming wireframes over a large pot and covering the frame with polyurethane foam. She had to manipulate the layers multiple times. Benglis wanted to enhance the statues and studied the methods used by foundries to cast bronze works. The four pieces were identical until Benglis experimented and added bronze elements into her coatings. East maintained its original size. The other three had layers of bronze, making what Benglis called a "collaged" bronze. The Graces (9.4.19) differs from the dark, brooding North, South East West. Benglis used wire mesh and cotton for the primary forms and poured polyurethane foam over the cylindrically shaped structures. Knots tied into the fabric form a result looking like crystals. The sculptures are named after Greek mythology, reflecting Benglis' ancestral country. Their crystalline shapes resemble something found under the sea, the translucent pink color otherworldly. The shapes spiral and shift as Benglis uses her ideas of material fluidity.

SCI-Arc faculty member Kavior Moon discusses the linkages between form, process, and materials in Lynda Benglis' latest self-titled exhibition of recent works at Blum & Poe Gallery.

[1] Retrieved from https://catalogue.swanngalleries.com...3&refNo=593423

[2] Inglot, J. (2004). The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments, and Myths, University of California Press, p. 28.

[3] Retrieved from https://www.nashersculpturecenter.or...artist/id/3831

[4] Retrieved from https://www.bonhams.com/auction/2610...omage-1985-87/

[5] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/artists/471