9.2: Feminist Art (1970-2000)

- Page ID

- 209045

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Women Who Defined Feminist Art

The term feminism originated from the French word "feminisme" and refers to the ideology and social movements advocating for women's equality. It gained popularity in the early 20th century, moving from Europe to the United States, and becoming synonymous with the Women's Movement. The word is a combination of "femme" (meaning woman) and "isme" (meaning social movement), and implies social change for women, ultimately leading to their right to vote in 1920. The "women's movement," referred to in the United States, had a critical turning point in the 1960s when it expanded into women's liberation. This second wave of feminism was directly related to the "capitalist economies which had drawn millions of women into the paid labor force, and civil rights and anti-colonial movements had revived the politics of democratization."[1] The advent of the Feminist movement incited a wave of core female issues such as reproductive rights, equal rights, sexism, and gender roles through art activism. The 1970s consciousness raising challenged the status quo, demanding the art world to change the inequality of art.

Feminist art challenges the domination of male artists to gain recognition and equality for women artists. (MOMA)

During the 1970s and subsequent years, cultural norms dictated that women were primarily responsible for childcare and homemaking duties, while men were considered the family's sole breadwinners. This societal expectation led to the emergence of the women's liberation movement, which aimed to secure political and economic rights for women in the workforce. The movement also sought to promote equal opportunities and fair compensation for women and access to domestic assistance to help balance their responsibilities at home and work. The movement played a crucial role in challenging traditional gender roles and paved the way for greater gender equality in society. Along with the second wave of feminism, women in the public arena remained marginal, and in the New York Whitney Museum, only 5% of the artists were female.[2] Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro created the Womanhouse project at the California Institute of the Arts. The project consisted of 17 rooms of visual representations of gender-stereotyped relationships.

This video is about Womanhouse, a feminist art installation created in 1972.

Female artists, including feminists, have been delving into women's spaces through metaphors in their large installations. One notable example is Judy Chicago's "The Dinner Party," which features a triangular table adorned with genital imagery on ceramic plates, honoring renowned women from history. Over the past three decades, feminism has opened doors for female artists, regardless of whether they identify as feminists. The famous art historian Linda Nochlin published the influential "Why have there been no great female artists?"[3]

"The fault, dear brothers, lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education—education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals. The miracle is, in fact, that given the overwhelming odds against women or blacks, so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence in whose bailiwicks of white masculine prerogative like science, politics, or the arts."[4]

Over the next two decades, momentous social changes took place from the perspective of women's issues, leading to greater freedom and opportunity. The Sixties witnessed the impact of sex, drugs, rock, and roll, along with the approval of the first oral contraceptive. The Seventies marked the beginning of "women's lib," women's "consciousness-raising," "no-fault" divorce, and Title IX, which provided equal funding for women's sports. The Feminist Art Movement aimed to link the building blocks of contemporary art with women. As a result, the movement sparked change, transformed societal attitudes, and positively affected gender stereotypes in the arts arena. The feminist movement emerged from ideas in the United States and Europe, eventually gaining traction in other countries and leading to greater acceptance of female artists. Artists in this section:

- Judy Chicago (1939-)

- Barbara Kruger (1945-)

- Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019)

- Jenny Holzer (1950-)

- Faith Ringgold (1930-)

- Ana Mendieta (1948-1985)

- Lorna Simpson (1960-)

- Marlene Dumas (1953-)

- Joan Semmel (1932-)

- Miriam Schapiro (1923-2015)

- Alma López (1966-)

Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago, born in 1939 in Illinos, is an accomplished American feminist artist. Her renowned work, The Dinner Party, is a large collaborative art installation. After studying at UCLA Art School, Chicago became involved in politics and graduated with an MFA degree in 1964. She began teaching at Fresno State College, where she instructed women to express themselves through their art. This evolved into a Feminist Art Program, which was highly popular among women. Alongside Miriam Schapiro, Chicago also transformed an old house at the California Institute of the Arts into a Womanhouse project featuring various artistic representations of women's domestic work.

Feminist artists began to explore women's spaces, using metaphors to create large installations like The Dinner Party (9.2.1). Chicago's installation depicted a large triangle table with genital imagery on the ceramic plates celebrating famous women in history. The project took five years due to the large size, 14.6 by 13.1 by 10.9 meters, with 39 different place settings. An embroidered table runner corresponds to the female figure plate and is set with silverware and a goblet. The inspiration for the Dinner Party was devised during a male-dominated dinner party Chicago attended. She felt women needed to be recognized at the table since they were mostly overlooked. The 39 plates represent historical or mythical female figures set like the Last Supper, with 13 people on each side of the triangle. Another notable 999 women's names are inscribed in gold on the exhibit floor. The meeting of 39 females was a powerful statement popular with the public; however, it was disparaged by critics who called it "vaginas on plates."

"The Dinner Party's positive celebration of female bodies and sexuality, its consciousness-raising about women's history and reclamation of women artists, and its subversion and revision of masculinist historical narratives, was an enormous popular success."[5]

This video takes you on a tour of Judy Chicago's seminal feminist piece from the 1970s, "The Dinner Party," in its permanent installation at The Brooklyn Museum. To check out a full video of Judy Chicago talking about the making of "The Dinner Party" and the specific imagery of each place setting.

Chicago's etched painting Fused Mary Queen of Scots (9.2.2) is a unique blend of fusing, etching, and kiln-fired spray paint that took over a year and a half to develop. Studying stained glass, she came across the Chinese art of painting on glass in sophisticated colors that replicated the porcelain look. The piece is a mix of yellow and blue radiating spiral lines surrounded by a light purple frame with handwritten words. Mary Queen of Scots was an ambitious woman who held the title of Queen of Scotland, which she acquired at six days old after her father died. She was found guilty of a plot to kill Queen Elizabeth and was beheaded shortly afterward, generating a divisive and highly romanticist historical character from the 16th century. The work brought ceramics forward from a craft to fine art using technical skills.

The Birth Project was a conglomerate of artwork designed by Chicago and completed by needleworkers artists around the United States, Canada, and other localized places worldwide. Needlework has always been considered women's work, a craft beneath most artists. Chicago led the collaborative project about women who created life and experienced childbirth from many points of view. The process of childbirth was not generally a subject brought up at parties or discussed at the dinner table, yet she brought up the issue upfront and personally.

Birth Tear Embroidery 3 (9.2.3) is a piece of artwork that is particularly striking. This work of art showcases a drawing of a woman in the midst of giving birth, initially created using a sharpie on a beautiful pink silk canvas. The artist has masterfully captured the pain and agony women often experience during childbirth, as evidenced by the color scheme utilized in the piece. The colors used in the artwork - red, purple, and blue - are meant to symbolize the stages of the tear that occurs during childbirth. The tear begins as a deep red color, then transitions to a more subdued purple hue before finally ending in a calm blue tone. Overall, this artwork is a powerful testament to women's incredible strength and resilience during the birthing process.

Barbara Kruger

Barbara Kruger (1945-) is an accomplished American feminist artist born in New Jersey, widely recognized for her captivating black and white photographs that are adorned with declarative captions in red and white. She holds the esteemed position of Distinguished Professor at the prestigious UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture, where she imparts her knowledge and experience to students. Kruger's work is particularly striking due to her impressive large-scale digital installations incorporating photography and collage, showcasing her mastery of art and technology. Her contributions have significantly impacted the art world, and her legacy inspires generations of aspiring artists."Overlaid with provocative graphics on authority, identity, and sexuality, her work confronts the power of mass media."[6]

The artwork titled, Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) (9.2.4) originally served as a poster for a pro-choice march held in Washington, D.C. back in 1989. It showcases the artist's perspective on gender inequality through black and white photographs of women from the 1950s, set against striking white text on red backgrounds. The image was created to bring attention to the ongoing debate surrounding reproductive rights, with the text boldly beginning with 'Your' to signify the solidarity of women across America in their fight for gender equality. Sadly, even in the 21st century, art from the 1970s continues to be a point of contention.

Over two decades, Kruger devoted her time and creative energy to designing and constructing installations that provided a fully immersive art experience for those who viewed them. One of her most notable installations, Belief+Doubt (9.2.5), boasts a visually striking black-and-white color scheme with well-placed pops of red to draw the eye. Through this particular piece, Kruger delved into the complex themes of democracy, money, power, and belief, utilizing text-printed vinyl to create an environment rich with words that viewers are compelled to read. Through her use of questioning, doubt is introduced into the experience, encouraging viewers to consider the underlying meaning behind her thought-provoking work. Kruger's expertise in design, specifically in the language of pop culture, heavily influenced her signature visual communication style throughout her career. She adeptly harnessed the persuasive power of pop culture images to convey her messages, utilizing short, impactful sentences to significant effect.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=657&height=491)

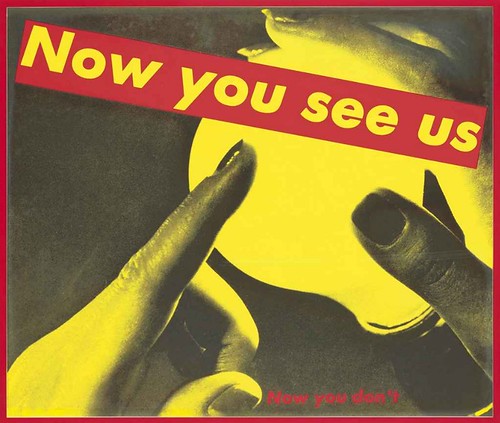

Kruger became famous for her aphoristic declarations of feminist principles, married with large photomontages. Untitled (Now You See Us) (x.x) is a change from black, white, and red art, including a deep lemon yellow instead of white. The yellow represents a lightbulb glowing bright yellow against a dark grey background. The direct yellow words are still against a red background in large font, while the second declaration is small, on the bottom, and red against a dark grey background.

Kruger, a renowned artist in the art world, has gained widespread recognition for her ability to express feminist ideals through her striking photomontages succinctly. In her piece titled Untitled (Now You See Us) (9.2.6), Kruger strays away from her usual color palette of black, white, and red, incorporating a vibrant lemon yellow hue instead of white. This particular shade of yellow symbolizes a glowing lightbulb illuminating against a somber grey backdrop, rendering the artwork's message even more powerful. The striking yellow words remain prominently displayed against a red background in a large font, drawing the viewer's attention to the powerful message being conveyed. The more minor, second declaration is situated at the bottom of the image, rendered in red against the same grey background, adding layer of depth and complexity to the artwork. Kruger's attention to detail and her ability to convey complex themes through her art has solidified her place as a respected voice in the art world.

Picturing Barbara Kruger is a five-minute portrait of this iconic artist. Narrated by Barbara Kruger with an original score by Nico Jaar featuring Kanye West’s "Blood On The Leaves," commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Carolee Schneemann

Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) was an American visual experimental artist who received an MFA from the University of Illinois. She began her career as an Abstract Expressionist painter but became disillusioned by the misogynistic heroism painters in New York City. Turning to creative performance art, Schneemann became involved with feminist art and exploring the female body. A stage backdrop, Four Fur Cutting Boards (9.2.7), is an extension into time and space as a moving sculpture that viewers can activate. The name of the artwork is from Schneemann's art studio, an old fur shop in Manhattan. The art is a conglomerate of oil paint, umbrellas, motors, lightbulbs, string lights, photographs, fabric, lace, hubcaps, printed papers, mirror, nylon stockings, nails, hinges, and staples on wood.[7] Schneemann painted her nude body and photographed herself interacting with the art becoming the subject and the object. Feminist art presents the female artist influenced by feminism—a double knowledge—of the female body.

As technology exploded, Schneemann experimented with laser printers creating painted prints of vulva images, part of the female genitalia. Vulva's Morphia (x.x) is a set of thirty-six pieces of art displayed in a clear plexiglass display. The in-your-face up-front rudeness of the imagery is balanced by a bitterly ironic text: "Vulva recognizes the symbols and names on graffiti under the railroad: slit, snatch, enchilada, beaver, muff, coozie, fish and finger pie . . . Vulva deciphers Lacan and Baudrillard and discovers she is only a sign, a signification of the void, of absence, of what is not male . . . (she is given a pen for taking notes)".[8]

A visual grid with text, Vulva's Morphia (9.2.8) are depictions of vulvas from an artist's point of view. The surrounding text is statements such as "Vulva decodes feminist constructivist semiotics and realizes she has no authentic feelings at all; even her erotic sensations are constructed by patriarchal projects, impositions, and conditioning." [9] Schneemann is taking back the female body and endorsing its powers without limits. For decades, she created art that challenged boundaries, attacked societal taboos, and kept it in our faces to ensure we do not forget.

“I lived what I call double knowledge: what I felt was true and could be a life experience, and then what the culture told me was absolutely not possible and had to be marginalized or denigrated.” She often used her own body in her work, both as a tool for extending the “action painting” of her predominantly male predecessors and as well as a way of, in her words, taking on “cultural taboos and repressive conventions” that existed in a sphere “starved in terms of sensuousness.”

Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer (1950-) is an American neo-conceptual artist known for her text installations. A Rhode Island School of Design graduate, she moved to New York City in the late 1970s to explore social and cultural theory. Holzer began her art career with Truisms, public works offering simple statements Holzer printed out on paper and wheat-pasted to buildings. The list of words came from her philosophy and literature classes; she condensed the entire text into a sentence. Moving from paper, Holzer turned to LED signs to flash her text on buildings or billboards. Stave (9.2.9) presents an LED sign in seven curved double-sided texts with red and blue diodes stating, "Would Like to Go Back Home." The delivery of words in large-scale installations earned her a spot in the famous Times Square Show.

A political activist, Holzer was looking to disrupt the passive information from sources that could be more damaging than helpful. In her Living Series, Protect Me From What I Want (9.2.10), are statements printed on stone, bronze, and aluminum plaques and placed on government buildings around New York City. These one-liner quotes were from a reading list while Holzer was a student. The short statements were about everyday necessities of life like breathing, sleeping, eating, and relationships. The messages represent the beginning of the information age and the jump start of social media.

During the early 1980s, Holzer created a body of work called Inflammatory Essays (9.2.11), consisting of posters influenced by political figures. Some of the excerpts read: "Rejoice! Our times are intolerable; Take courage, for the worst, is a harbinger of the best; Only dire circumstance can precipitate the overthrow of oppressors; The old & corrupt must be laid to waste before the just can triumph; Contradiction will be heightened; The reckoning will be hastened by the staging of seed disturbances, and The apocalypse will blossom."[10] The posters have been recreated on colored paper and attached to the walls in lines of color for impact.

Jenny Holzer's lithograph Inflammatory Essays on display at Tate Modern.

Faith Ringgold

Faith Ringgold (1930-2023) is an American artist born in Harlem during the Great Depression. Her parents were descendants of the Great Migration (the movement of six million African Americans from the rural South to the Northeast, Midwest, and west coast to escape the South's Jim Crow Laws). Ringgold's mother was a fashion designer, and her father was an avid storyteller. Ringgold inherited both qualities from her parents, who are the driving force in her artwork. She was also influenced by the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural art revival of African American dance, music, and politics in Harlem, a predominantly African American neighborhood.

Ringgold began her painting career after graduating from art school, inspired by Pop Art, African art, Cubism, and Impressionism. She explores self-portraits and addresses some of the concurrent Black Power movements in the 1960s. Early Works #25: Self Portrait (9.2.12) is an oil painting on canvas in a tight red circle outlined in white. Circles dominate the portrait behind Ringgold, the string of pearls, and the two circles on her chest. Her arms are folded across her waist, and she is wearing a multicolored blue dress with a very determined gaze on her face. Ringgold comments, "I was trying to find my voice, talking to myself through my art."[11] In the 1970s, Faith Ringgold collaborated with her mother, Willi Posey, a well-known tailor in Harlem, to make several textile works. Echoes of Harlem (9.2.13) was Ringgold's first quilt and her final collaborative project with her mother. The composition unifies four different fabrics in a regular rhythm and frames thirty faces, displaying a variety of individual expressions. Together, the faces represent the many life stories present in Harlem. In subsequent years Ringgold began constructing narrative quilts that portray different aspects of African American life in the United States.

Ringgold and other black women artists pursued a black cultural consciousness grounded in the reclamation of black historical memory and pan-African spirituality.[12] Framing the issues of black female identity, Ringgold created art inspired by trips to Africa, creating crafts stitching together unique storytelling quilts. One of Ringgold's most famous art pieces is Tar Beach (9.2.14 & 9.2.15), a painted scene on fabric and then quilted the work. The quilt depicts a scene of a family on the roof of their apartment building in Harlem overlooking the George Washington Bridge. The flat roofs on buildings were usually finished in black tar to seal them from the rain and snow. The scene is after dinner, the adults sit around a card table, and the children are lying on blankets wishing they could fly over the city. The story is based upon Ringgold's family memories where "flying among the stars on a hot summer night, Cassie becomes a heroic explorer overcoming obstacles,"[13] which expresses freedom and self-possession. Tar Beach (x.x) closeup depicts the attention to detail with the two children lying on the "tar beach" looking up at the sky.

Faith Ringgold is an artist whose remarkable contribution to feminist art is worth noting. In 1969, she joined the Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), a group that broke away from the male-dominated Art Workers' Coalition (AWC). Throughout her career, Ringgold was a professor in the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego, until her retirement in 2002. Her extensive publications testify to her noteworthy contributions to the art world.

Faith Ringgold on fighting to get women and African-American artists into museums and the power of art. Faith Ringgold is one of America's most gifted and generous visual storytellers. Ringgold is best known for the painted story quilts in which she draws on African American folklore tradition, often to dramatize—to humanize—institutional and national histories.

Ana Mendieta

Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) was a Cuban artist born in Havana in 1948. Her family left Cuba during the Cuban Revolution under Operation Peter Pan and moved to the United States. After completing her MFA at the University of Iowa, Mendieta relocated to New York City to pursue her art career. As a displaced Cuban, Mendieta's art focused on themes of feminism, identity, and belonging inspired by the avant-garde community. Her art often incorporated elements of nature, reflecting her spiritual and physical connection with the earth. Mendieta's work was instrumental in highlighting the ethnic and racial expressions of different cultures and giving voice to previously marginalized female artists of color as part of the feminist art movement.

"Through my earth/body sculptures, I become one with the earth…I become an extension of nature, and nature becomes an extension of my body. This obsessive act of reasserting my ties with the earth is really the reactivation of primeval beliefs…[in] an omnipresent female force, the after image of being encompassed within the womb, is a manifestation of my thirst for being".[14]

Mendieta was fascinated with nature and created her female silhouettes amidst earth, mud, sand, and grass in her Silueta Series (Silhouette). In Untitled (9.2.16), she sculpted a naked earth-body lying in rock outcrops covered with twigs, weeds, and flowers, symbolizing connection with the earth. The contrast between the granite-colored rock, light brown female body, and green grass with white colors highlights various feminist art issues. The presence of a nude woman can represent a mother figure, a young woman, or refer to a Mayan deity, lx Chel, a feminine life force throughout her work. Mendieta was a vital figure in the Body Art Movement and seamlessly integrated Land Art into her natural environment art process. Using found objects, she aimed to merge humanity into one whole world, blurring the boundaries between art movements.

After visiting Pre-Columbian archeology in Mesoamerican areas, Mendieta interpolated the female theme into tombs, earth, and rocks. She carved the figure into the dirt as it filled with blood, in Silueta Works in Mexico (9.2.17) displays. In the Mayan culture, blood was used as a source of nourishment for all the deities. The ephemeral artworks show how fragile the human body is when pitted against nature. The earth body sculptures are a powerful depiction of feminist art installations. It is regrettable for the art world as we lost Mendieta at an early age. It is unknown if she was pushed or jumped to her death from the 34th floor of her high-rise apartment, and her husband of 8 months was acquitted for any part he may have played in Mendieta's death.

"Ana Mendieta's art, even when she was alive, was the stuff of myth," wrote Nancy Spero summing up the feminist Cuban American artist whose late works are currently being shown at Galerie Lelong in Chelsea.

Lorna Simpson

Lorna Simpson (1960-) is an American photographer and multimedia artist from New York who attended the High School of Art in Brooklyn. Simpson traveled to Europe to hone her skills in photography, where she documented people and then graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in painting. Continuing her education, she received an MFA from the University of California at San Diego, emerging with a style called photo-text—photographs that included text—a pioneer of conceptual photography.

One of Simpson's most famous photo-text works is Five Day Forecast (9.2.18). The bold display of an African American woman has a cropped torso. She wore a white dress contrasting against the rich brown color of her arms folded across her chest. Words are displayed across the top and bottom of the pictures labeled Monday through Friday, and ten white words—misdescription, misinformation, misidentify, misdiagnose, misfunction, mistranscribe, misremember, misgauge, misconstrue, and mistranslate—on black rectangles across the bottom of the display. The word mis/miss is an exchange in the power of words and a shower of recriminations.[15]

Flipside (9.2.19) pairs the art of an African mask with the art of photography but from the backside of each style. The woman has a black dress and black hair against a black background. The mask is set against a black backdrop, hence the name Flipside. The curves in both photos relate to the popular hairstyle in the early 1960s, traditionally worn by African American women. The plaque below reads: The neighbors were suspicious of her hairstyle. The hair and the mask are seen as primitive cultural pieces of art confirming the identity of African Americans as the flipside of a 45-vinyl record, with the topside being the hit of the time and the flipside being the lesser quality.

"Lorna Simpson’s work has not only challenged stereotypes of African Americans but created a visionary space for the contemplation of humanity itself and what it means to be American, given the complicated cultural inheritances we've been given." —LeRonn Brooks, associate curator at the Getty Research Institute. Lorna Simpson has been a pioneering artist for 30 years. She is a leading voice in a generation of American artists questioning constructed historical narratives and the performative crafting of identity.

Marlene Dumas

Marlene Dumas (1953-) was born in Cape Town, South Africa, spending her childhood by a river in Western Cape. Dumas attended the University of Cape Town to study art before moving to the Netherlands and transferring to the University of Amsterdam. She majored in psychology instead of art, planning to become an art therapist. Dumas still lives in the Netherlands and is one of the country's most prolific artists. During her life in South Africa, she identified as a white woman of Afrikaans descent and saw firsthand how Apartheid separated white from black people.

Dumas said she does not paint people; instead, she creates an emotional state focusing on race, violence, sex, death, the contrast of guilt or innocence, and even tenderness or shame. She frequently took photographs of friends and used them as reference material along with photos in magazines. Dumas did not paint using live models, only reference material. Her subjects were political, famous, or erotic, primarily controversial. Albino (9.2.20) is one of Dumas' psychologically charged paintings with a grey-pink-blue face. The small red-brown eyes are set on each side of a large wide nose with full lips and a small chin. The large forehead is enveloped in white light with a widow's peak at the hairline and painted with spontaneous brushwork.

By choosing a subject whose very existence complicates the notion of racial categorization and by rendering his skin tone and hair color in a sickly green hue, Dumas insisted on destabilizing the division between black and white.[16]

Self Portrait at Noon (9.2.21) is a portrait of the painter with her well-known curly long hair. The ghostly look of silver and black is thematic in most of her work. The sickly green reappears on the body in coordination with small beady eyes set apart over a small nose and little lips showing just a hint of teeth. The black shirt offsets the light colors, contrasting an otherwise monotone painting.

An interesting set of four paintings was created in the early 1990s called the Four Virgins (9.2.22 & 9.2.23). The miniature figurative portraits are made from gouache and India ink and are unrecognized anonymous women. The name designates the virginal women, yet Dumas allows viewers to experience and make up their minds. Each portrait is similar in color and painting style, making the group a set of black and white with blue highlights, which sets off each painting.

After the Four Virgins, Dumas painted a child with green hair, brooding dark eyes, with red and blue colored hands called Painter (9.2.24). Her daughter was finger painting one day with paint all over her hands and an inspiration for the concept in the painting. The baby-like body with bluish skin tones reveals the combination of abstract painterly qualities of drawing and watercolor. The figure is incomplete, a concept Dumas used to remove any real context and inaugurate a more allegorical idea.

Movie stars, terrorists, babies, and strippers – actor and art collector Russell Tovey picks some of his favorite works from Tate Modern's introspective and intoxicating survey of Marlene Dumas' career.

Joan Semmel

Joan Semmel (1932-) is an American feminist art painter, teacher, and writer well-known for her large-scale portraits. Born in New York, she earned a BFA from the Pratt Institute. Semmel spent the next decade in Spain "gradually developing broad gestural and spatially referenced painting to compositions of a somewhat surreal figure/ground composition…(her) highly saturated brilliant color separated (her) paintings from the leading Spanish artists whose work was darker, grayer and Goyaesque".[17] After returning to the States, she earned an MFA from Pratt Institute and started her unique figurative style of erotic themes.

Once back in New York, Semmel joined the feminist movement and devoted herself to gender equality. Semmel paints her nudes from the perspective of a woman's point of view; they undermine the male stare and reclaim female subjectivity. Nudity in art has ebbed and flowed through thousands of years and across the globe. The tradition of nudity was broken with the fading of neoclassicism art in the 19th century, and "any artist in our culture to present herself to the public nakedly is a deliberate and studied act."[18] Using herself as a model, Semmel photographs the scene she wants to paint and abstracts the images with lines and color. In Self-Made (9.2.25), Semmel combined her feminist art ideas with sexual liberation and painted nude forms in sexual poses. The combination of two female forms in a sexual encounter is rendered with one figure in bright colors foreshortened against another in more skin tones of color.

"Reclaiming the female body for women, Semmel asserted women's rights to create and control their representation and aesthetic pleasure."[19]

Another of Semmel's paintings is Touch (9.2.26), from the female's perspective in the frame. Foreshortened, it is a moment of touch between two people. The erotically charged image subverts the usual position of a full-body female nude lying on a bed and provides the audience with a direct vision of the artist. The warm color tones of the two bodies contrast with the cool colors of the pillow and wall behind the couple. Semmel has continued to paint nudes into the 21st century, although her art is from the perspective of a reflection in the mirror. The paintings reflect an aging woman in a metaphysical state of exploration.

This program explores the work of an artist who was instrumental in turning paintings of women's bodies into painting about women's lives. A feminist and chronicler of the female body and sexuality, Semmel makes lush and painterly canvases rarely seen in the art world of the nineties. Seen on this program is an exhibition of her latest canvases that depict the aging female body as seen in the spas and athletic clubs of present day New York.

Miriam Schapiro

Miriam Schapiro (1923-2015) was a Canadian feminist artist who used a variety of mediums, such as paint, print, and metal, to create her art. After graduating from the State University of Iowa with a Ph.D., she moved to New York City to study with the Abstract Expressionists of New York. She has been coined 'the leader of the feminist art movement' and began her abstract expressionist art career after the birth of her first son. In 1967 she moved to California, becoming the first artist who used a computer to create art. Schapiro collaborated with Judy Chicago opening the first feminist art program and the California Institute of the Arts and the Womanhouse, an installation about women and the female experience. Schapiro started experimenting and expanding the materials she used in her art and included items that marginalized domestic craft. The assemblage Barcelona Fan (9.2.27) emphasizes Schapiro's interest in fabric and the art of sewing, creating a brilliant color fan using tactile materials.

The open fan is constructed with alternating rows of red and white and small additions of green and blue in this bigger-than-life fan.

"I wanted to validate the traditional activities of women, to connect myself to the unknown women artists…who had done the invisible 'women's work' of civilization. I wanted to acknowledge them, to honor them."[20]

In the mid-1980s, Schapiro deviated from her natural materials and created a large-scale sculpture called Anna and David (9.2.28) on Wilson Boulevard in Arlington, Virginia. The sculpture was based on a painting called Pas de Deux which is over 3.5 meters high and weighs half a metric ton. The brightly painted aluminum is a whimsical pair of dancers that conveys movement in animated poses with unabashed pleasure. The primary colors are vibrant in hues giving the sculpture an animated quality. Schapiro's career spanned over four decades, creating art in abstract expressionism, minimalism, computer art, and feminist art. One type of art she created was fabric collages or, as Schapiro calls it, 'femmages'—a combination of fabric and textiles—depicting women's work.

An interview with the artist Miriam Schapiro.

[1] Freedman, E. (2001). No turning back: The history of feminism and the future of women. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. (p. 5).

[2] Freedman, E. (2001). No turning back: The history of feminism and the future of women. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. (p. 319).

[3] Nochlin, L. (2015). Female artists. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

[4] Nochlin, L. (2015). Female artists. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

[5] Doss. E. (2002). Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford. (p. 184).

[6]Retrieved from: https://www.riseart.com/guide/2418/g...t-art-movement

[7] Retrieved from: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/196031

[8] Clark, R. (2001). Carolee Schneemann’s rage against the male. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artandde....artsfeatures1

[9] Ibid.

[10] McKenzie, L. (2018). "Jenny Holzer, the feminist artist behind Lorde's Grammys gown message, isn't a stranger to the fashion world." Los Angeles Times. (10)

[11] Retrieved from: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/211047

[12] Doss. E. (2002). Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford. (p. 198).

[13] Retrieved from https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/86892

[14] Ramos, E. Carmen (2014). Our America. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

[15] Taylor, R. (2010). Lorna Simpson exhibition catalog at the Tate. Retreived from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/simpson-five-day-forecast-t13335

[16] Retrieved from: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/160222/albino

[17] Semmel, J. (2015). Joan Semmel: Across Five Decades. Alexander Gray Assoc., LLC.

[18] Semmel, J., Modersohn-Becker, P., Antin, E., & Withers, J. (1983). Musing about the Muse. Feminist Studies, 9(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177681

[19] Doss. E. (2002). Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford. (p. 184).

[20] Doss. E. (2002). Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford. (p. 187).