5.3: American Colonial (1700-1800s)

- Page ID

- 134991

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

European laws were deeply ingrained in the American colonies, and a strict patriarchal system reigned supreme. Men believed they were superior to women, a long-standing doctrine that impacted every aspect of society, including political power, wealth, religious practices, concepts of morality, and child-rearing practices. Finally, in 1900, all states granted married women limited control over their finances. Women's groups tirelessly fought for political equality, leading to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which granted women the right to vote and paved the way for economic and social reforms.

Early colonists had little time for art, survival, and religion dominated the people's lives. As soon as the colonies stabilized and more settlers came, craftsmanship and artistry grew. Large, ornate churches and palaces did not exist; outsized marble sculptures were unimportant in the small, plainly painted churches. The new colonists turned their skills to smaller, portable endeavors; portrait painting, silversmithing, furniture making, and proper outlets for creative people. Hundreds of silversmiths flourished, turning valuable everyday items into elegant, hand-designed, and crafted works of art. Painting portraits became one of the first significant artist roles, a luxury item reflecting a person's economic or religious status. A person usually poses with a favorite possession, further developing their position in the community. As the interest in portraits grew, training for artists increased; no longer the purview of an iterant folk-art painter, the education and skills of artists flourished, and portraits became an influential art form for the new colonies.

Some early artists in the colonies were considered folk artists, commonly self-trained, acted as an apprentice, or had minimal instruction. Their art was used to decorate homes with single or family portraits characterized by a more straightforward, naive style and generally did not follow rules of proportion or perspective. Many folk artists had limited resources and were itinerant, traveling from place to place depending on the location of the individual who wanted a portrait. Artists include:

- Ruth Henshaw Bascom (1772-1848)

- Susanna Paine (1792-1862)

- Sarah Goodridge (1788-1853)

- Henrietta Johnston (ca 1674-1729)

- Mary Roberts (?-1761)

- Sarah Bushnell Perkins (1771-1831)

Ruth Henshaw Bascom

Born in Massachusetts, Ruth Henshaw Bascom (1772-1848) married a minister and spent her time traveling and supporting his religious endeavors, only starting her artwork later in life. She was an avid record keeper. Many of her diaries survived, giving historians a look at her life, the local community, the weather, information about the art supplies she purchased, and how much they cost. Very few notations about income were noted about specific artwork; however, her diaries indicate she created over 1400 pieces. She lived comfortably on the average income; however, art supplies would be costly, depending on the frame style and the glass, and she generally charged one to three dollars or bartered, a common practice. As she traveled, she painted and believed idleness was not a proper behavior and noted, "I sketched Miss H. Goulding and two images for little S. Booker and L. Jones – for want of other means to employ my leisure."[1]

Ruth Henshaw Bascom gained recognition for her exceptional talent in needlework, particularly in creating samplers. Samplers were a popular form of embroidery during the 18th and 19th centuries, serving as a way for young girls to practice and showcase their stitching skills. Bascom's samplers were meticulously crafted, featuring intricate patterns, alphabets, and decorative motifs. Her work often included biblical verses, commemorative elements, and personal details such as her name, age, and completion date. Her samplers are known for their fine needlework, vibrant colors, and attention to detail.

Bascom used pastels and crayons to create her profile images, generally life-sized from the bust upward for adults and the waist for children. In the image, Cynthia Allen (5.3.1) wore a typical hairstyle, a bun on the back of her head, and dangling curls in the front (frequently called spaniel curls). The sheer shawl on her shoulders was an ordinary fashion item. The image is a life-like yet exact copy of the people and a common technique for the itinerant artists of the time. Bascom's work exemplified the skills and artistry of early American needlework. Her samplers are highly collectible and appreciated for their historical and artistic value. They provide insights into the lives and accomplishments of young women during that era.

Susanna Paine

A stunning portrait of Eliza, Sheldon Battey, and their beloved son Thomas Sheldon Battey (5.3.2) was masterfully crafted using oil paint on a smooth wooden background. The family is elegantly posed on a luxurious settee, with rich, dark red drapes providing the perfect backdrop for this exquisite masterpiece. Each family member's attire is carefully chosen to reflect Sheldon's thriving business career, adding a touch of sophistication to the scene. Paine demonstrated an incredible level of skill and attention to detail in capturing the essence of each member of the family. From the intricate details of Eliza's hat and collar to the delicate ruffles on young Thomas's collar, every aspect of the painting is rendered with a truly breathtaking realism level.

Sarah Goodridge

Sarah Goodridge (1788-1853) was raised on a farm with little opportunity for art supplies and learned to draw using sticks in the sand on the kitchen floor. Goodridge displayed a talent for art from a young age and began her artistic training in Boston. As a teenager, she moved to Boston, studied with a painter, opened her studio, and became one of the most productive miniatures painters. Goodridge developed a friendship with Gilbert Stuart and his daughter Jane, having him critique her work. Goodridge gained recognition for her skillful execution of miniature portraits, which were highly popular during the 18th and 19th centuries. Miniature portraits were small-scale, finely detailed paintings typically created as personal keepsakes or gifts. They were often worn as jewelry or displayed in small frames. Goodridge was so successful she frequently painted three portraits in a week of many Boston notables. Her preferred medium was watercolor painted on ivory.

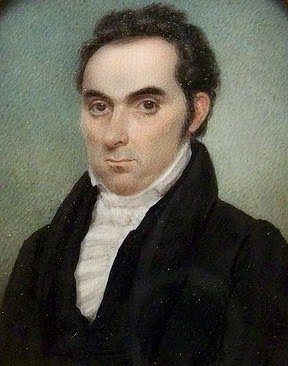

One of her favorite customers was Daniel Webster. Historians believe Webster, a politician, who was married and had children, carried on an affair with Goodridge for years. Over multiple years, she painted several portraits of him while they took on correspondence. However, when his wife died, he remarried a wealthy woman, remained a senator, and continued to visit Goodridge. The painting Daniel Webster (5.3.3) was one of the images she did of Webster, dressed in a typical black coat and ruffled shirt, but whose expressive eyes stare back at the painter as the rest of his face remains stoic.

Goodridge's portraits captured the likeness and personality of her subjects with great precision and delicacy. She painted notable individuals such as politicians, military officers, and prominent figures of her time. However, she became most renowned for her intimate self-portrait, "The Beauty Revealed." "The Beauty Revealed" (5.3.4) is a miniature portrait of Sarah Goodridge herself. The artwork depicts her partially exposed breast, delicately painted with exceptional detail. The painting caused controversy and fascination, challenging societal norms and expectations regarding portraying female nudity. Sarah Goodridge's work showcased her technical mastery and attention to detail. She was celebrated for her ability to capture both physical likeness and emotional depth in her portraits. Despite facing challenges as a female artist in the male-dominated art world of her time, she achieved recognition and success for her art.

_by_Sarah_Goodridge.jpg?revision=1)

Sarah Goodridge (February 5, 1788 – December 28, 1853; also referred to as Sarah Goodrich) was an American painter who specialized in portrait miniatures. She was the older sister of Elizabeth Goodridge, also an American miniaturist.

Henrietta Johnston

It is believed that Henrietta Johnston (ca 1674-1729), born around 1674, hailed from France. Her family eventually relocated to England before settling in the United States was thought to be from France, and her family migrated to England and then to the United States. Henrietta Johnston was a pioneering American portrait painter and one of the earliest professional female artists in the American colonies. Although her birth date and early life details are not well-documented, she was likely born around 1674. With her honed craft in pastels and her familiarity with English society through her husband's family, she gained recognition in England for her portraits. After relocating to South Carolina and marrying for the second time, she became the Southern colonies' first known female artist and portraitist. Her work typically depicts the person from the waist up, with males portrayed and females in chemise. Despite the limited opportunities for women artists of her time, Henrietta Johnston established herself as a successful and highly sought-after portraitist, particularly in Charleston in street clothing, South Carolina, where she resided and worked.

Occasionally Johnston went to New York, and there she completed the portrait of Anna Cuyler (Mrs. Anthony) Van Schaick (5.3.4), the daughter of the mayor of Albany. The image was typical of Johnston; the facial appearance of Anna is vague, perhaps nostalgic, her face and hair unadorned and straightforward. The chemise may have been made of good material; however, it also seems plain, unlike those with elegant lace and satin. Johnston's portraits were a true reflection of her expertise in capturing the essence of her subjects' personalities and physical features. Her portfolio boasted portrayals of distinguished characters such as political leaders, planters, and other prominent members of the colonial South Carolina society. Her portraits typically featured detailed renderings of clothing, accessories, and background elements that provided insight into the status and lifestyle of the sitters. Unfortunately, only a few of Henrietta Johnston's works have survived, making it challenging to assess her artistic style and contributions fully. Henrietta Johnston's career was cut short by her untimely death in 1729. Still, her pioneering role as a professional female artist in the American colonies paved the way for future generations of women artists. Her work is a testament to the talent and determination of women who defied societal expectations and made significant contributions to the arts.

_Van_Schaick.jpg?revision=1)

Mary Roberts

Mary Roberts (died 1761) was a highly esteemed painter from South Carolina who made significant contributions to the field of painting. While her birthdate remains a mystery, she is widely recognized as the first female painter in the region. Her remarkable accomplishments also made her the first woman in the colonies to use watercolor on ivory for her miniatures, setting a standard for future artists. Despite the challenges she faced as a woman, Mary Roberts persevered and became the sole breadwinner for her family after her husband's untimely death. Only three of her miniatures remain, believed to have been painted around the 1740s based on the intricate clothing and wigs depicted. Mary Roberts' legacy as a trailblazing female artist continues to inspire and captivate art enthusiasts worldwide.

In 2006, an intriguing discovery was uncovered at an estate in England. A collection of five miniature ivory pieces were found and later identified as the work of Mary Roberts. One of these miniatures stood out in particular, a small yet stunning gold-cased piece featuring Henrietta Middleton (5.3.6) as the subject. The watercolor painting of the young girl donning a delicate lace dress is exceptional, showcasing remarkable detail in her large blue eyes and intricately patterned lace. Furthermore, Thomas Middleton (5.3.7), believed to be Henrietta's cousin, is also portrayed in a similar white top and adult-style hair. While Mary Roberts' repertoire may be limited in quantity, her contributions to the world of art undoubtedly hold immeasurable value and should be preserved and cherished for generations to come.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=530&height=711)

Sarah Bushnell Perkins

Sarah Bushnell Perkins (1771-1831) was an exceptionally skilled artist who received her top-notch education at her father's academy, where she polished her artistic talents to perfection. Perkins persevered and excelled in her craft despite the challenges of losing her mother at an early age and becoming the caretaker and primary provider for her younger siblings after her father's passing. Her exceptional works were initially attributed to Beardsley Limner, but in 1984, they were finally acknowledged as her own, proving her indisputable talent. Perkins specialized in painting portraits of her family members and employed advanced contrast and modeling techniques that outclassed her peers. One of her most remarkable pieces, Colonial Dame (5.3.8), showcases her absolute mastery in using a muted color scheme and limited palette and her ability to create unconventional poses and direct eye contact with the viewer. Perkins' artistry is genuinely remarkable and continues to impress and inspire.

[1] Lois S. Avigad (Fall 1987). Ruth Henshaw Bascom: A Youthful Viewpoint. The Clarion 12:41. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/american_folk_art_..._4_fall1987/40

[2] Laura R. Prieto (2001). At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America. Harvard University Press. p. 20. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=0b...page&q&f=false