6.5: Kinetic Art (1950s – 1960s)

- Page ID

- 124391

Introduction

Op Art produced static images which gave the impression of movement. Kinetic art moved through mechanical methods and motors or viewer interaction, using natural air currents in space. The forerunner to kinetic art is found in the simplicity of Duchamp's bicycle in unplanned freewheeling motion. Kinetic art became well-known after World War II and an exhibition in 1955 in Paris entitled Le Mouvement. Mobiles, originated by Alexander Calder, was a typical style of kinetic art. They were suspended in the air and moved as air flowed. Mobiles were not solid structures; instead, they were made of pieces balanced by structural elements and brought a new perception of dimensional art beyond sculptures. Calder believed kinetic art strove to "lift the figures and scenery off the page and prove undeniably that art is not rigid."[1]

Kinetic art also examined the intersections between the mechanics of science and the beauty of art based on the ideas of three-dimensional sculptural movement. Most of the kinetic artists based their work on mechanized movements, using a machine to create motion. Jean Tinguely was one of the early artists who collected paraphernalia, which he attached into a whimsical object and set in motion with a motor. Artists used elements of Dadaism, reclaiming found objects to use in their sculptures and putting them in motion by mechanized means or air currents.

Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder (1898-1976) was born in Pennsylvania, his family well-known artists. His grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder, created the immense William Penn statue in Philadelphia, and his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, was a sculptor who produced multiple public sculptures. Calder's mother was a portrait artist. When his father was diagnosed with tuberculosis, the family moved to Arizona in 1905 and then to California. At the Calder home in Pasadena, the young Calder set up his first studio using wire to make doll jewelry for his sister. The family moved between New York and California, although Calder stayed in California to complete high school. Because his parents were opposed to him pursuing art, he majored in mechanical engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology, and in 1919, he became a hydraulic engineer after graduation. After visiting his sister in Washington, he was inspired by the mountains and returned to New York and study art. To expand his knowledge, he went to Paris to study, became part of the intellectual scene, and made friends with other artists, including Joan Miró and Marcel Duchamp. Initially, he created abstract paintings, soon learning he preferred sculpture and the dimensions over flat painting. After he met his future wife, they married in 1931 and lived in Connecticut with their two children. In 1963, he moved back to France, always inspired by the French countryside. He generally gave his works French names, irrespective of where they were installed.

Calder is known for his uniquely engineered constructions, probably the result of his engineering background. His original sculptures were small, moveable, balanced wood and wire characters. In the late 1930s, Calder began to create larger, abstract sculptures, some of their stationery and others moveable, initially powered by machines before moving to power by air currents. The stationary sculptures on the ground were labeled "stabiles" and those hanging with movement named "mobiles." Calder explained the difference in the terms as; "The mobile has actual movement in itself, while the stabile is back at the old painting idea of implied movement. You have to walk around a stabile or through it – a mobile dances in front of you."[2] In the 1960s, he made standing mobiles named "animobiles." When he went anywhere, Calder usually carried some type of wire and pliers, using the wire to "sketch" a form he noticed, much like drawing in air. He made his final sculptures from metal and wire; however, he had to use wood during World War II because the government used all the metal in the war effort. When asked what his favorite color was, he generally replied, red. Black and white were used for differentiation, red the focus. When Calder constructed his works, he always designed a process the sculpture could be shipped and reassembled. He packaged the work in flat packs and included detailed assembly information based on numbers and color codes.

As seen in Black Spray (6.5.1), Calder's small, hanging mobiles were designed to engage the viewer's senses. The thin black metal and wire pieces create changing shadows on the background, altering each element and its shadow as the air currents arbitrarily moved the pieces. As the metal pieces move, their relationships modify, demonstrating the laws of variation found in life.

In contrast to the thin, delicately balanced mobile is the immense sculpture of Flamingo (6.5.2). The 45.3 metric ton steel sculpture was painted in the color known as "Calder red." Calder wanted to differentiate the sculpture from the background of black and steel buildings. The sculpture is also constructed with broad curves in the juxtaposition of the square and rectangular windows and buildings. The arched forms generated a natural feeling, the curvature of structures so large viewers can walk through and under the form, sensing the scale of the artwork.

In the sculpture Five Empties (6.5.3), Calder named the work after the five voids found in the structure's base, anchored to the ground to form his two different structures; the mobile and the stabile. The two arms provide the pivot for movement as the petals or shapes catch the wind blowing against the colorful, thin, flat surfaces, rotating the arms and petals. When a viewer is standing in the empty spaces, the petals are not visible, seemingly separate pieces, while the petals are seen from afar. Calder made the construction visible in the sculpture with the bolts, rivets, and welding marks, adding texture and interest. The matte paint on the petals contrasts with the shiny arms and branches, compelling the viewer to look at each piece and appreciate its construction. Depending on the speed of the wind, the artwork can look like gentle flowers dancing in the breeze or frantic whirling forms.

The Four Elements (6.5.4) is located in Stockholm and stands 9.1 meters high. Created in 1961 for an exhibition, the work was composed of four separate sculptures, each one containing a motor for movement. Made from metal sheets, the sculptures were painted in distinctive bright colors, defining the different shapes to represent air, water, earth, and fire. However, he did not specify which shape represents a specific element the viewer can choose. Each of the different structures rotates as they move, bringing the four different elements to life. The four parts have a dissimilar focus; the surface and light reflection result from the shapes and colors—the volume of an element changes as it moves through space, bringing the viewer different sides and angles.

_at_Moderna_Museet_in_Stockholm.jpg?revision=1) Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): The Four Elements (1961, sheet metal and paint, 914.4 cm) by Frankie Fouganthin, CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): The Four Elements (1961, sheet metal and paint, 914.4 cm) by Frankie Fouganthin, CC BY-SA 4.0Jean Tinguely

Jean Tinguely (1925-1991) was born in Switzerland and lived in Basel as a child, his father a shopkeeper and his mother a maid. At first, he worked as an apprentice decorator where one of the other decorators encouraged him to attend the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel. He learned about Marcel Duchamp, Dadaism, and Constructivism as well as meeting his first wife. He worked as a decorator and started his early wire sculptures. In 1952, they moved to Paris, becoming part of the artist community pursuing unusual pioneering concepts. He was preoccupied with the movement, capabilities, and noises of machines. In 1955, he participated in the exhibition, 'Le Mouvement,' the first significant demonstration of kinetic art and his sculptural machines defined as 'Méta-Matic.' His concepts satirize automation and manufactured material goods. During the Peinnale de Paris at a museum in Paris, Tinguely displayed a machine, run by a gasoline engine as it moved about, created drawing, sprayed a lily-of-the-valley scent into the air, and inflated a balloon. The machine at the museum marked the sudden rise in his career. During the 1950s, he created multiple machines demonstrating the destructiveness of modern mass production. One machine buried the audience in the paper. Another kinetic work had parts and pieces of a machine spewing out loud, cacophonous noises, and a different display even self-destructed.

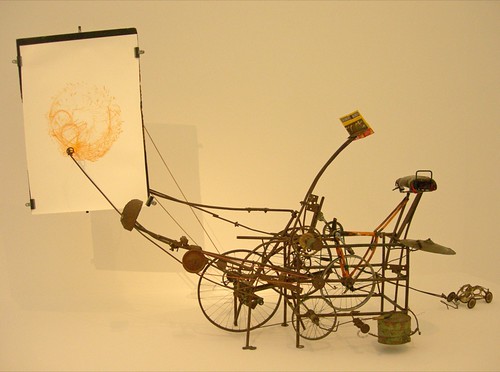

In the 1960s, Tinguely changed direction and began to create machines with an emphasis on movements. Cyclograveur (6.5.5) used a bicycle as the primary base and added parts from cars, other bicycles, baby carriages, and even a seat from a motorcycle. He connected the gears and wheels and installed the drawing board located beyond the pedals. A viewer mounted the bicycle seat and pushed the pedals to make the sculpture move, causing the rod to draw on the board. He also added mallets, a drum, and a cymbal to generate clunking, rickety noises, adding to the user's adventure. Tinguely created his works to criticize society's mechanization. A review in the newspaper Volkskrant stated, "the grotesque and utterly useless, but diligently moving constructions, which you bump into here, are trying to be a witty provocation—certainly a challenge to the mechanization of all that is human."[3] He frequently painted his sculptures black bringing a homogeny to the parts.

Requiem pour une feuille morte (6.5.6) was composed of multiple components and pieces mounted on a frame along the wall. He carved each circle from wood and painted the wheels and metal parts black. Then he mounted them along eight different sections for easy assembly. The circular forms are interconnected with wires, and the motion is controlled by a tiny piece of metal painted white.

Tinguely found a large number of wooden models assigned to be burned. He rescued the models to construct the immense structure Méta-Harmonie IV (6.5.7) using the wooden parts, other old wheels, multiple types of small objects he found, percussion instruments, and even a cowbell. He did not use any working drawings; he only constructed a base and added parts. Tinguely made the movements slower and the sounds more muted, punctuated by sharp, quick sounds. He also used the natural color of any of the objects spreading the different colors throughout the structures. Tinguely said, "My contraptions do not make music, my contraptions use sounds and I play with those sounds. I sometimes build sound-mixing machines to mix sounds and then let the sounds go, give them their freedom."[4] Tinguely's large and small rattling machines were revolutionary, bringing not only people into his art but giving them a concert of creaks, thumps, bangs, and clangs. His active art amazed children and adults alike.

Jesús Rafael Soto

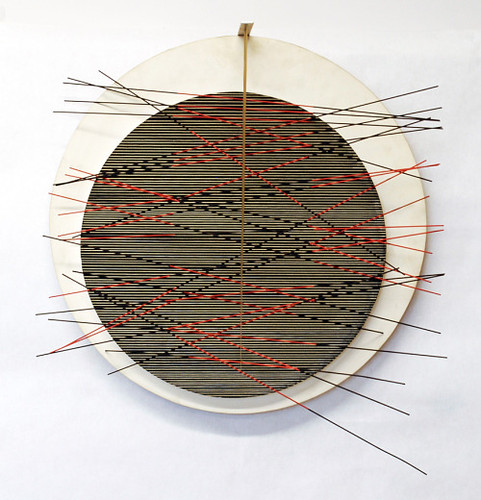

Jesús Rafael Soto (1923-2005) was born in Venezuela. As the eldest child, he had to help support his family by painting posters for cinemas, learning to draw portraits along the way. Soto gained the support of a local bishop who helped him obtain a scholarship to the Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Artes Aplicadas. He was able to complete classes in art and art history. In 1950, Soto moved to Paris, experimenting with Cubism and Constructivists and Op Art. Eventually, he became part of the new three-dimensional movement, associating with Jean Tinguely and Victor Vasarely. As spectators moved in front of optical paintings to view movement, Soto wanted the viewer to participate in his work. He created artwork responsive to external changes and reactions in space. Soto started with geometric forms and linear constructions based on more industrial materials of steel, paint, nylon, or synthetics. He wanted to give the viewer an experience founded on the interactions of solid forms and the spaces surrounding the shapes, blurring the differences of certainty and illusion. Circle with Red and Black (6.5.8) is an illusion using thin black lines painted on the wooden background with red and black rods traversing the circle at multiple angles. As the rods disrupt the horizontal lines on the circle, the relationships and balance of the colors change and appear to move.

La Esfera (6.5.9) was formed on a base of white metal to create a frame attached to the cement base. Soto used 1,800 slender, hollow aluminum poles suspended by stainless steel rods only a few millimeters thick. The orange color of the poles gave the sculpture the effect of a large sphere or sun suspended in air, shimmering and changing colors based on sunlight or wind. The sculpture is one of the famous sights in modern-day Caracas.

The Penetrable (6.5.10) was one of Soto's signature series and defined as his most aspirational work. He did not want it to sit in a museum, seen by viewers passing by and untouched.

Instead, he wanted people to touch and walk through the sculpture and physically become part of the artwork (6.5.11). Soto used thousands of yellow polyvinylchloride (PVC) tubes and hung them with wire from the white steel frame. As the viewers traverse through the sculptural tubes, they become part of the artwork. As Soto stated, "My concept of space is very different from that of the Renaissance, where man was in front of space, he was the viewer, the judge of that space...[With] the Penetrable, I reveal that man...is part of space. And this is the sensation of those who enter them, and the feeling of joy and elation that you witness is similar to getting in the water and being completely liberated from gravity."[5] The work appears as a geometric structure. However, it does not have a solid surface. The entire sculpture can be altered by natural elements of the wind and rain or by the viewers themselves. It is a continually changing artwork, inviting to the audience as part of the art.

Naum Gabo

Naum Gabo (1890-1977) was born in Russia, his father was an engineer. Gabo studied at Munich University as a medical and science student, where he discovered abstract art through classes in art history. Gabo moved to Paris to live with his brother, who was an artist. After World War I, he moved back to Moscow, making early constructions from cardboard and wood. He experimented with kinetic artwork based on geometric forms; unfortunately, most of his early work was destroyed. In 1928, in Germany, Gabo taught at the Bauhaus until he fled to London to escape the ascent of the Nazis. After the war, he, his wife, and his daughter emigrated to America and lived in Connecticut. Gabo's work was imaginative and creative based, using his scientific background to construct his innovative sculptures. The sculptures were constructed of multiple materials, including plastics, different metals, large rocks, plexiglass, even fishing lines, and motors to provide movement.

Originally, Gabo constructed a maquette he wanted to create into a full-scale fountain, Revolving Torison (6.5.12). A director from the Tate Gallery presented the concept to a benefactor who consented to fund the project. Gabo designed to fountain to be made from stainless steel. The outer diagonal edges included a series of jets spraying water as the sculpture rotated every ten minutes. The water jets change during the rotation from minimal to maximum spray. At first, Gabo constructed tiny models of monumental sculptures in motion he wanted to create. He also wanted to incorporate materials from the modern era and change the concept of space as spherical instead of angular. He used the idea of spheres and created multiple sculptures with different materials.

One Spheric Theme (6.5.13) was constructed of stainless steel, and the sculpture appears to be continuously curved lines. The sculpture was built with two circles attached with springs to develop depth and the concept of weightlessness.

Constructed Head No. 2 (6.5.14) was based on Gabo's concept of form in space instead of the usual sculptural idea of mass. He used different planes to create the same volume in space as it would in a solid mass, making multiple figures or heads in this way instead of solid mass. Although the forms were fragmented into different planes and parts, he still manipulated the space to create an expressive face. Gabo used galvanized iron, forming them into planes. The figure appears to be looking downwards, the head slouched forward with its hands clasped, almost prayerlike. Based on the light and movement of the viewer, the head changes its emotional perception.

Yaacov Agam

Yaacov Agam (1928-) was born in Rishon LeZion, now a city in Israel, then part of the Mandate Palestine. His father was an Orthodox rabbi, and Agam was educated in the mysticism of the Kabbala, concepts that remained with him throughout his lifetime and influenced his art. Agam was educated at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design and then moved to Switzerland. In 1951, he settled in France and lives still lives there, a place he married and had three children. Agam loved to experiment and is one of the pioneering artists of kinetic art. He believed all things in conventional art were visible, and he preferred to create the invisible, or experiences one has not yet understood. He stated, "I am not an abstract artist… Abstract art shows a situation on a canvas. I show a state of being which does not exist, the imperceptible absence of an image."[6] Agam's work ranged from immense installations to smaller individual works, all based on the concept of engaging the viewer in the aesthetic experience. The artwork changes depending on where the viewer stands, visual revelations of the three-dimensional installations or agamographs – a series of seemingly static images which transform at different angles. Agam used rainbow colors in their pure form, color establishing the complexity of his work. His work was kinetic, abstract, and frequently included colors, light, and sound, creating an unusual sensory experience. He said of his work, "My intention was to create a work of art which would transcend the visible, which cannot be perceived except in stages, with the understanding that it is a partial revelation and not the perpetuation of the existing."[7]

Eighteen Levels (6.5.16) was constructed on the concept of repetition of a fundamental geometric form, or as Theo Van Doesburg termed it, 'elementarist' forms. In this structure, the straight-line stainless-steel poles rise in progression as the lines are modified on both their axis or an appearing off-center axis, shifting and changing. From one position, the poles appear static; however, the simplest movement by the viewer completely changes the positioning of the poles. Agam used an unpretentious geometric shape of a line to maximize the diversity of change and movement.

The Fire and Water (6.5.17) fountain was one of his later sculptures representing unexpected movement by incorporating fire, water, color, and metal, all moving in different patterns. Agam used the colors of the rainbow based on the spiritual belief heaven was represented in the rainbow and was the covenant in God. The sculpture changed if the viewer stood in one position or moved around the fountain as water might be jetted to the left or right, spraying upright or tumbling down. At the same time, fire shot upwards in a huge burst or a soft glow as the layers of the structure moved in different directions, continually changing the colors. Agam believed he brought an added dimension to his work beyond the ordinary three dimensions based on the interrelationships of many movements and transformations occurring simultaneously.

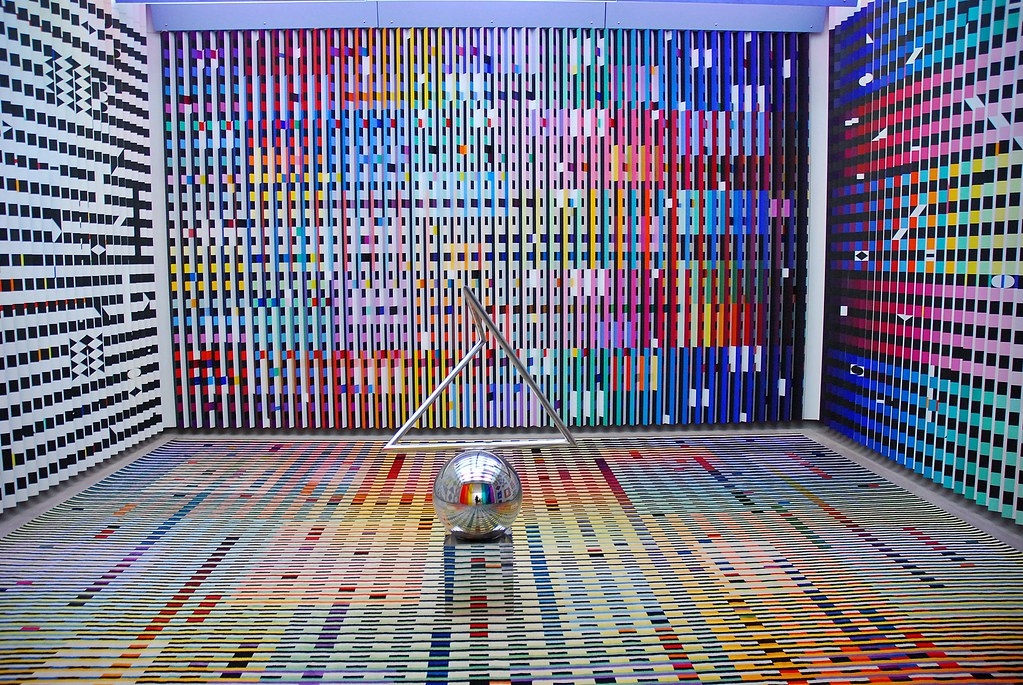

The room at the Elysée Palace in Paris (6.5.18) was commissioned from Agam as the elaborate ground floor of the presidential palace and later moved to the museum. The carpet in the room had 180 colors and a multitude of glass panels in the ceilings and walls. In the middle of the room stood the shiny chrome ball (6.5.19), reflecting the constantly changing colors and patterns of the room depending on the viewer's location. Three walls had lenticular painted slats, while one wall had multi-colored glass doors transporting the light. The viewer was inside the artwork, each viewer creating a different experience at every angle, an infinite number of possibilities. Agam brought his religious beliefs into much of his work, and he thought the room represented the infinity of God, and the elements in the room were abstracted into a unified space.

The kinetic artists brought unique ideas of integrating the concept and capabilities of technology into art, replacing the static forms with dynamic constructions. Kinetic art was a lively movement, thriving for over a decade. Although the unique junk-art style of Tinguely and the mobile art pioneered by Calder eventually faded, the concepts of mobility and integration of technology remain in art today.

[1] Retrieved from https://themadmuseum.co.uk/history-of-kinetic-art/ (17 December 2020)

[2] Retrieved from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/alexander-calder-848/who-is-alexander-calder (30 December 2020)

[3] Retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/sequitur/2016/04/29/schoenberger-tinguely/ (4 January 2021)

[4] Retrieved from https://www.tinguely.ch/en/tinguely/tinguely-biographie.html (4 January 2021)

[5] Retrieved from https://unframed.lacma.org/2020/05/26/lacma-acquires-blue-penetrable-kinetic-artist-jes%C3%BAs-rafael-soto (5 January 2021)

[6] Retrieved from

[7] Retrieved from https://www.lifa-research.org/en/artists/agam/