2.4: Mughal and Rajput (1530 – Late 18th century)

- Page ID

- 120736

Introduction

During the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, artwork in India was based on three different religious principles, Islamic, Hindu, and Buddhism, illustrating India's culture and beauty. The Mughal painting style started around 1530 when the Mughal emperor returned from exile in Persia to his home in India. While in Persia, he learned about miniature painting favored by the Persians. He brought two Persian artists back to India to create artwork for him, the beginning of a style that flourished under the reigns of several subsequent emperors. Mughal was the main style in India until the middle 1600s, and by the end of the seventeenth century was replaced by the Rajput style. In the late seventeenth century, the royal courts of Rajputana supported a distinct style; each court developed different styles based on common standards. Four primary schools supported the Rajput type, each one creating a distinctive substyle.

Since the Mughal painting was influenced by Persian art, the works were miniatures, painted on individual leaves that became a collection or set or made into a book, a common form in Islamic art. The Rajput painting also took the form of miniatures; however, they were not bound into a book; instead, each painting was wrapped, tied with a ribbon, and stored to be used on special occasions. Mughal painters themselves were followers, living in the courts, creating works based on the directions of the ruling class. Their work was sophisticated with specific methods of painting. Rajput artists generally were ordinary people, less educated. Their art was based on religious concepts and traditions of the community, not the courts.

Mughal Art

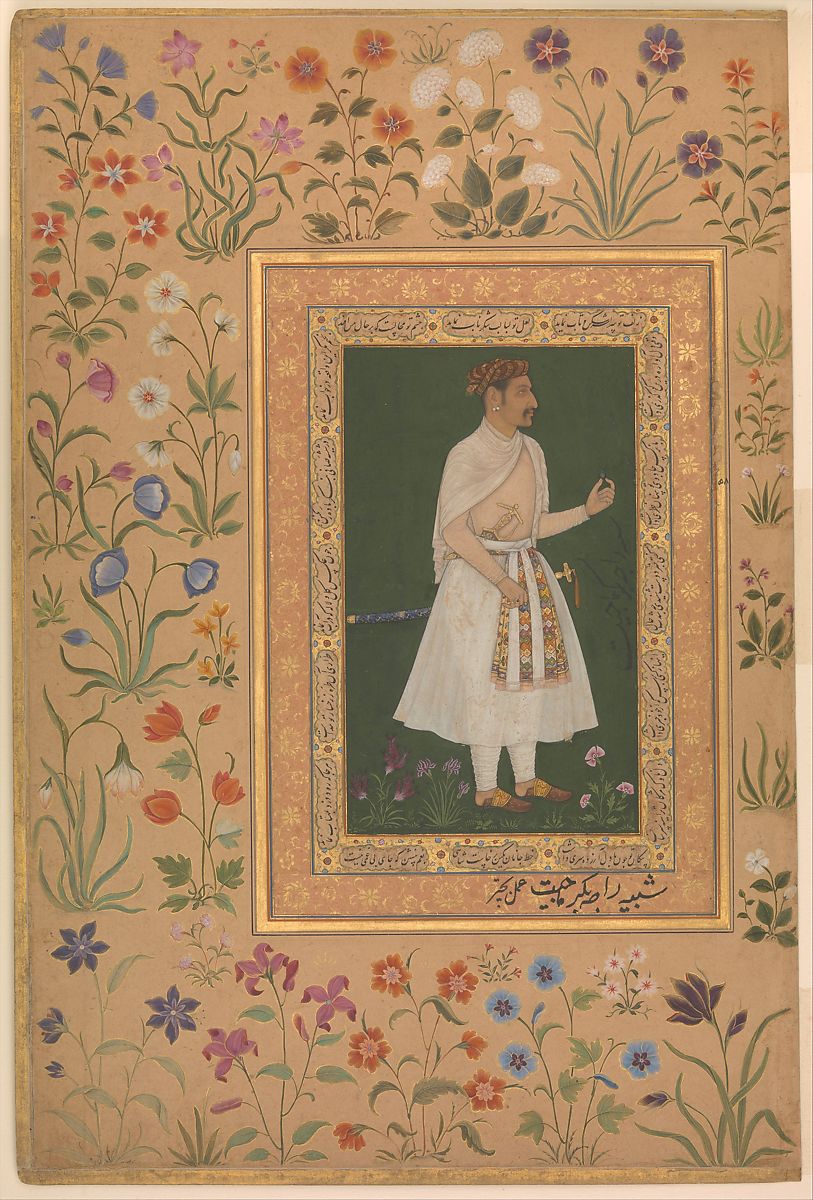

In 1605, when Jahangir became emperor, he continued supporting the arts; however, he brought his style and standards. He wanted each painter to create their works without collaboration and focus on animals, plants, and portraits. He commissioned several books to be written and illustrated, lavishly decorated with borders, stamped images, golden accents, and treated leather. The work of the individual artists became recognizable and the standard of the time. Generally, the artists lived in court and went sent out to illustrate the events of the court and the elite.

Mughal art did not portray the more erotic images found in previous Hindu works; instead, the small miniature art was focused on paintings of the noblemen dressed in specific clothing. The influence of Islam defined the art, and the small paintings did not include women. Colors were more muted and dominated by tones from nature. Calligraphy became part of the artwork with quotes from writers or the Quran. The borders became an important part of the images based on ornamentation styles found in Islamic artwork. The paintings were generally miniature, and gold was a critical color to help accent areas of the picture and elaborate knives and swords.

Ustad Mansur

Although he only lived a short time, Ustad Mansur (1590-1624) was a prominent painter of animals, birds, and plants. He was known to document and paint birds or animals not previously known to the local population, including the dodo and Siberian crane. He earned the title ustad (master), and the emperor Jahangir bestowed on this outstanding painter the title Nadir-al-‘Asr (unequaled of the age). The painting of birds (2.4.1) had the elusive dodo bird in the center of the picture, never before seen in realistic detail. The blue-crowned parrot in the upper left, the horned pheasant in the upper right, and the bar-headed goose in the bottom all display the different details captured by Mansur. They are all set against the pale, misty green and the cloudy sky, appearing as all the birds were in one place.

Because the emperor favored Mansur, they frequently traveled together so Mansur could paint and document the wonders of the world the emperor saw. When the emperor discovered a new type of bird, he stated,

"I ordered them to catch two or three of these birds, that I might ascertain whether they were waterfowl and were web-footed or had open feet like land birds. They caught two . . . One died immediately, and the other lived for a day. Its feet were not webbed like a duck's. I ordered [nadir al-asr] Ustad Mansur to draw its likeness."[1]

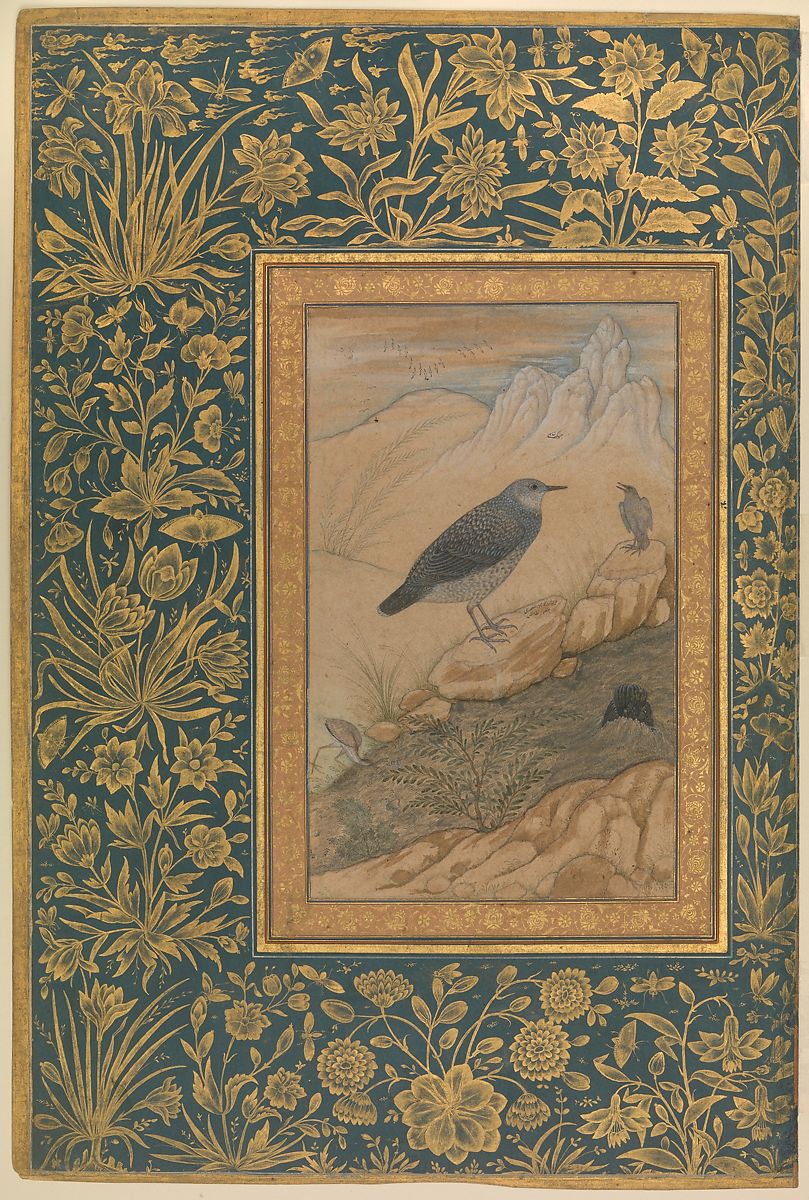

The small image of the Diving Dipper (2.4.2), painted with muted colors, appears to be standing in his natural environment. Mansur added realistic detail to the bird and created a masterful background with the mountains jutting behind the bird. Around the whole image is an example of the flower gilded frames the artists added to any image with gold paint to stand out from the dark blue.

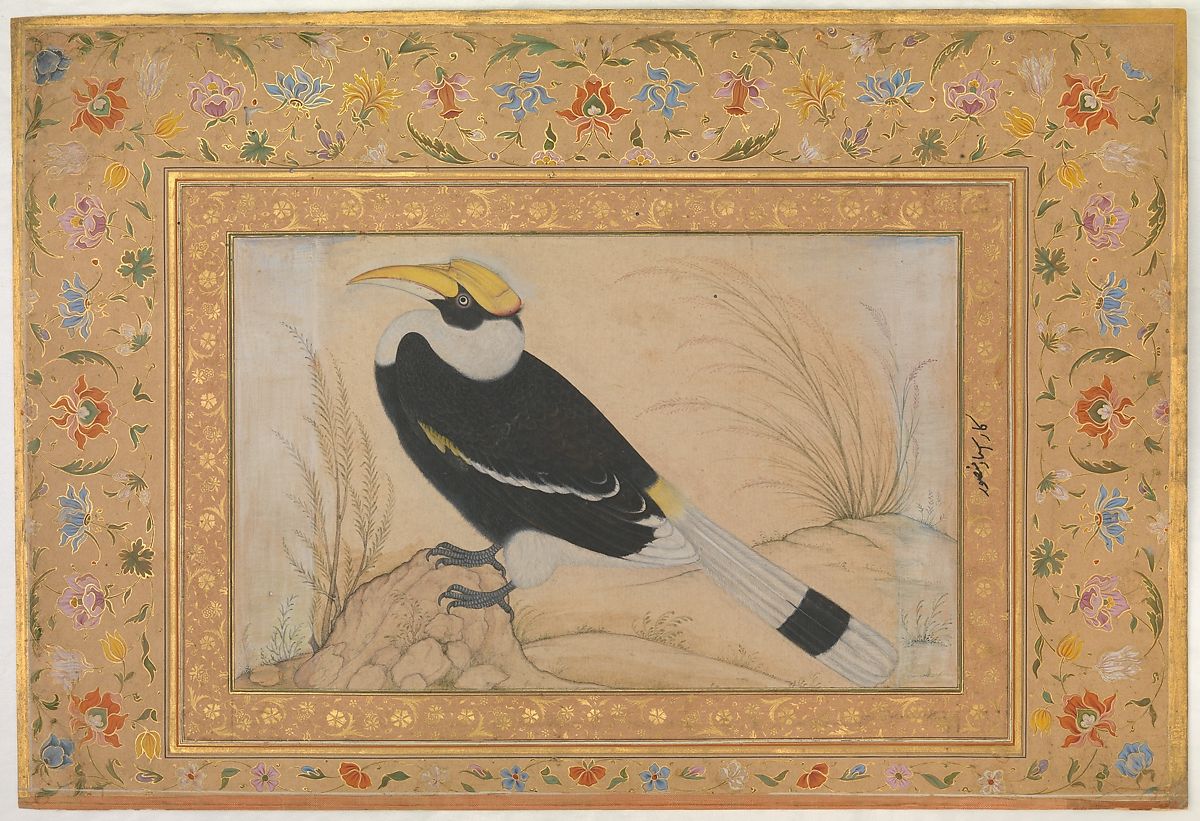

The Great Hornbill (2.4.3) was a large bird, 132 cm, with striking black and white feathers and a yellow bill. Although Mansur perched the bird on a rock, the forest was the usual habitat for hornbills. He probably did not see the bird in the natural setting; however, Mansur generally placed his birds in a neutral background.

Govardhan

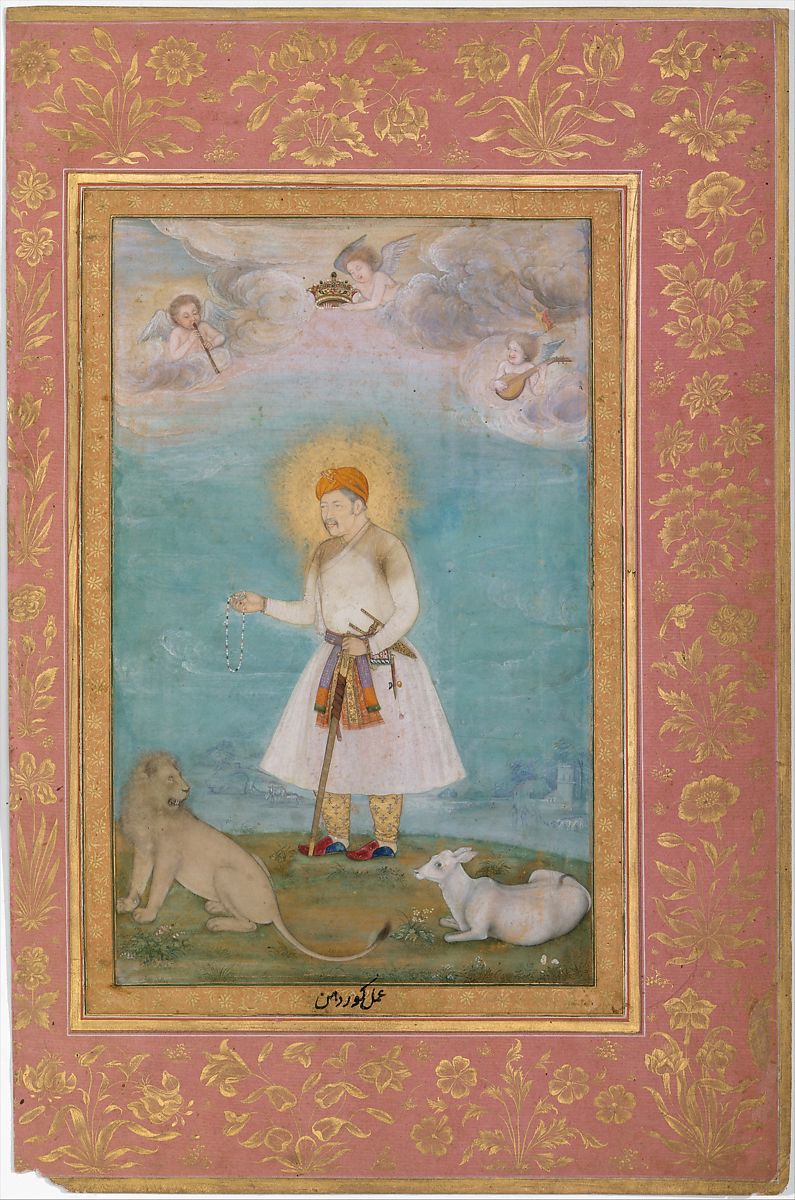

Govardhan (1596-1640) was the son of a painter, and he worked in the emperor's court. Govardhan used muted but rich colors in his work to depict different people performing daily activities. After Emperor Akbar died, Govardhan painted his image, Akbar with Lion and Calf (2.4.4), with the peaceful display of the lion and the calf, but is it peaceful? Images of the lion and calf are a common theme in early Hindu art and are frequently used by artists as symbols, and here the calf lies uneasily as the lion bares his teeth.

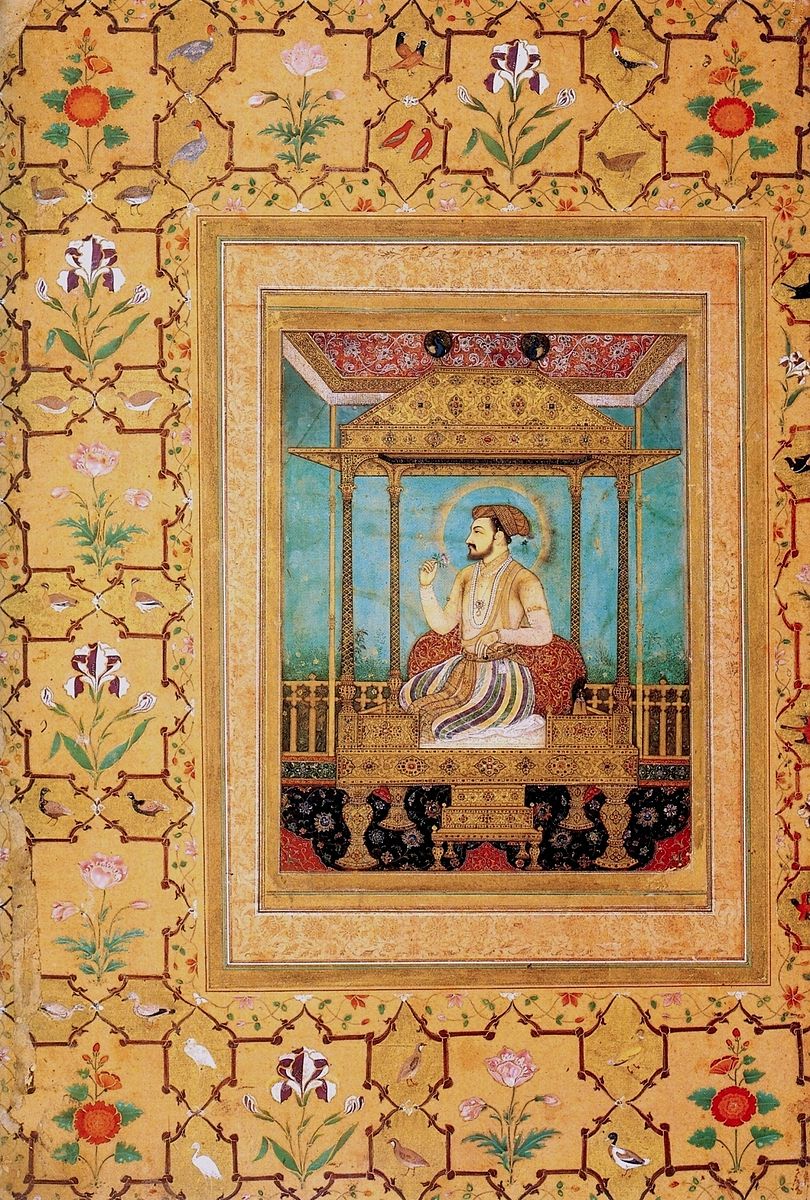

Shah Jahan on the Peacock Throne (2.4.5), made in the early 1600s, was the seat for Mughal emperors, a place for the emperor to sit high above the ground while close to the heavens. The throne was encrusted with jewels, pearls, and gold, and the detailed painting by Govardhan captures the shah sitting on a throne, a hint to the luxury of the real one. Govardhan liked to use a soft turquoise for the backgrounds and encircled the heads of the rulers with a yellow sphere. Both of the images have common detailed floral patterns on the borders.

Bichitr

Bichitr (1585-1660) was a long-lived and active painter in the courts of multiple emperors, focusing on portraits of the court and its activities and often thought to be the best of the court Mughal artists. His early work was done in the usual softer and muted colors of the period; however, he used a brighter color palette with hard lines in later works. After studying European art, like Govardhan, he frequently incorporated small cherubs in his career.

One of his early paintings, painted in a muted style, is a self-portrait (2.4.6). He was dressed in Hindu-designed clothing commonly found in earlier Hindu courts. The small image is surrounded by elaborate gilded framing with multiple flower designs.

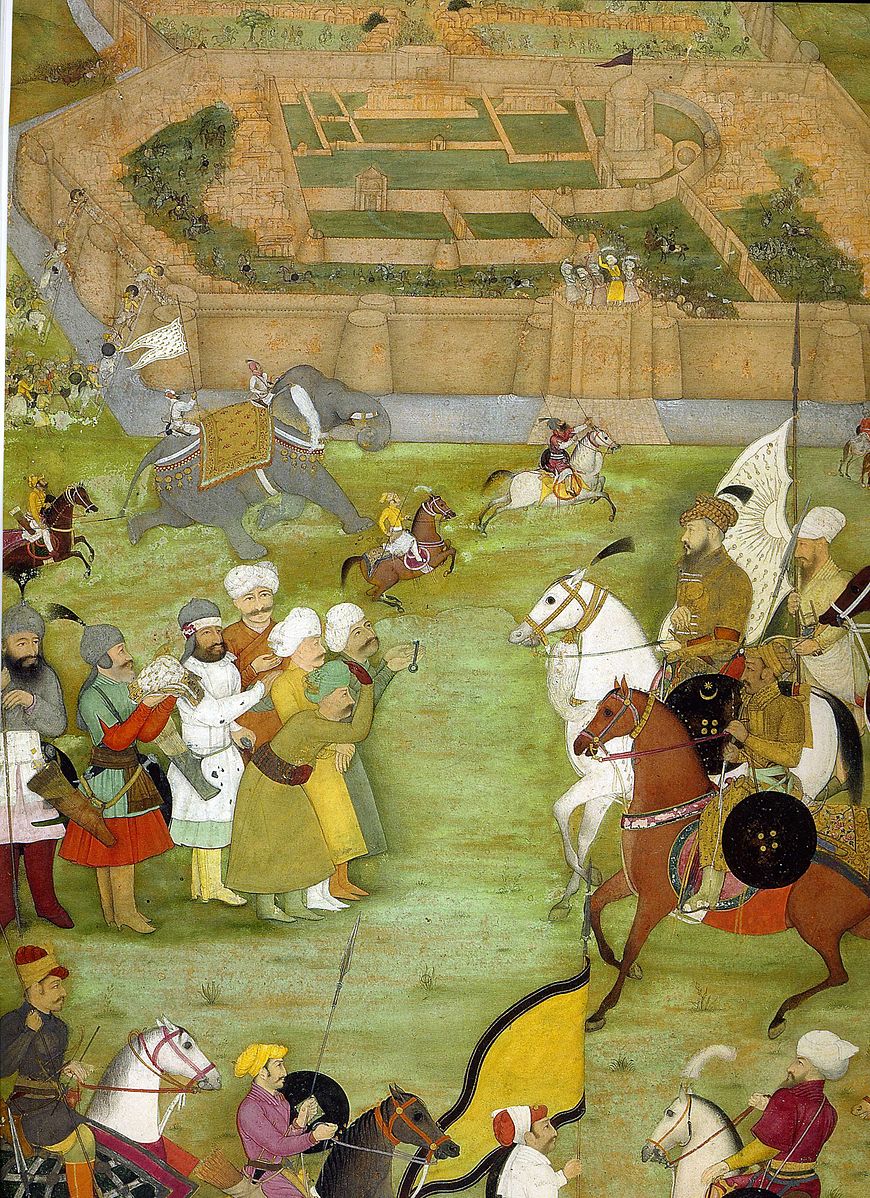

The Padshahnama

Shah Jahan is known for the Taj Mahal monument he had constructed in honor of his wife. He commissioned another major work, the history of his reign, written and illustrated with portraits of the court luminaries and scenes of their activities for ten years. Fourteen court artists worked on the forty-four illustrations considered by some historians as the best of the paintings from Mughal artwork. When the English invaded India, the manuscript and its paintings were taken as a gift to the king by Lord Teignmouth, who stated, "This is the most splendid Persian manuscript I ever saw. Many of the faces are very well painted, and some of them are portraits."[2]

When Shah-Jahan ascended to the throne after his father's death, Bichitr painted one of the ceremonies (2.4.7) for the Padshahnama when the shah's sons came to watch, and other nobles in attendance pledged their fidelity. The shah is centered at the top of the painting, and a lamb and two lions below him symbolize peace in his reign. The detail in the painting demonstrates the skill of Bichitr. All of the people are painted in profile, each dressed in specific clothing, unique patterns in the headdress, robes, and belts. Every space in the image is highly ornamented with designs of flowers, calligraphy, and gilded objects. The symmetry is evident in the balanced composition. The emperor is seated in the middle above the golden table wearing a blue gown.

Another illustration, Mughal Soldiers and Civilians (2.4.8), painter unknown, depicted the surrender of the Kandahar garrison to Shah Jahan and his soldiers. The shah, riding his white horse, was dressed in understated battle clothing. The image is flatter with less embellishment and gilding, a detailed scene with less decoration.

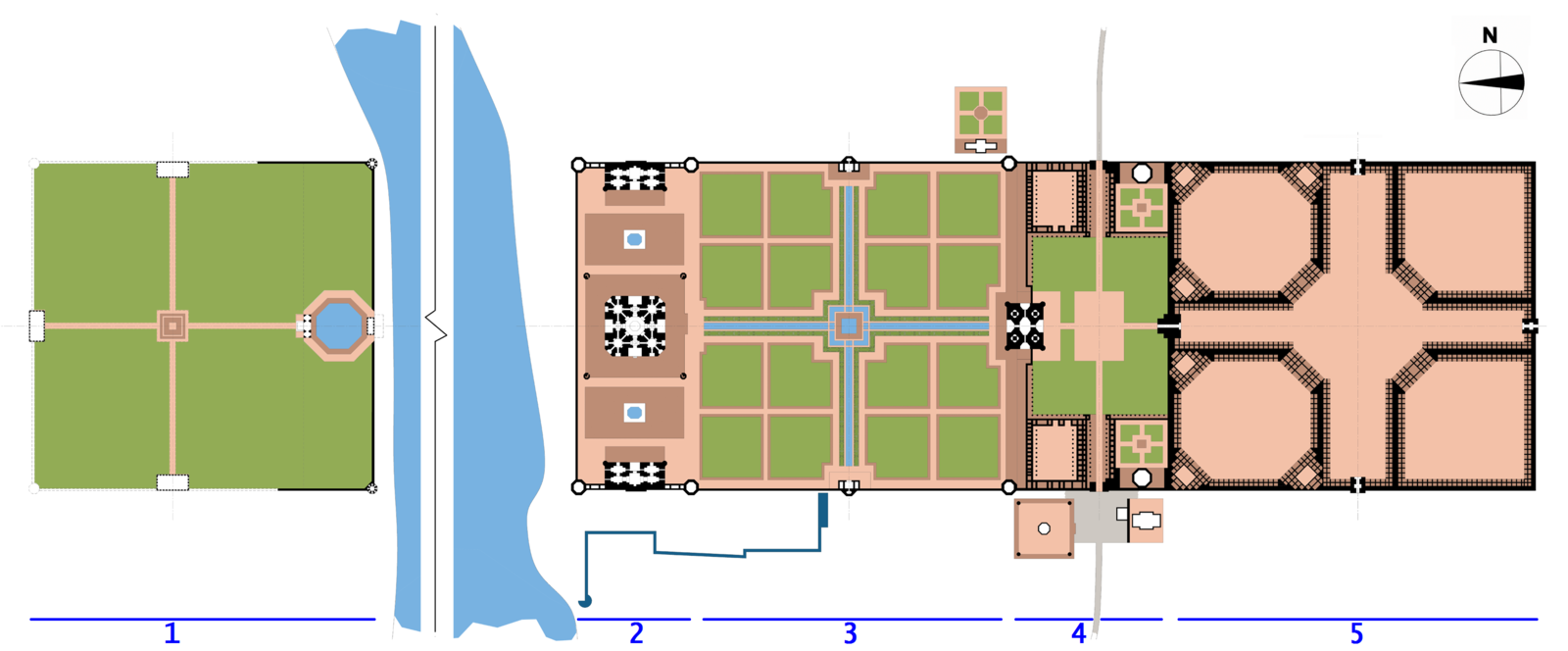

Taj Mahal

Shah Jahan was a big supporter of the arts, his most notable achievement was the Taj Mahal (2.4.9), the tomb he commissioned after the death of his wife, an undertaking ongoing for sixteen years. The tomb in Agra is by a river with elegant gardens and reflecting pools, considered the finest architectural accomplishment in the Indo-Islamic region. The structure presents a perfect architectural symmetry of domes, towers, and arches, all created from the brilliance of the white marble and the exquisite workmanship. The placement of the garden and pools leading to the tomb adds to the spectacular perspective of the building. The four minarets give the complex additional dimension.

The Taj Mahal complex (2.4.10) was divided into five sections. The moonlight garden (1) lay to the north of the Yamuna River, and the riverfront terrace (2) facing the river contained the mausoleum, mosque, and jawab, a building to mirror the mosque and create symmetry. In the center is the Charbagh garden (3), where the pavilions were located, adjoining the jilauikhana (4), a place to accommodate the tomb attendants and two other tombs. The jilauikhana meant 'in front of the house,' or a large courtyard transitioning between the street and royal buildings.

The Taj Ganji (5) along the back of the complex, originally a bazaar and place for the caravans to stop. The central gate is sited between the jilaukhana and the garden. Levels gradually descend in steps from the Taj Ganji towards the river. Contemporary descriptions of the complex list the elements in order from the river terrace toward the Taj Ganji.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Taj Mahal Site Plan, Public Domain

The interior of the tomb is shaped like an octagon with openings on every side. On the ground floor are the cenotaphs (2.4.11) of the tombs for both the shah and his wife (the actual tombs are in the basement) located in the center of the octagon encircled by octagonal lattice screens (2.4.12) made of elaborately carved marble. The screens are inlaid with a pattern representing flowers, all made from precious stones. Each leave and petal was carefully matched for the correct hues and perfectly placed in the marble. The marble was precisely cut and fitted in the style parchin kari, a form of decorative art in the region. The walls were adorned with lapidary inlay as well as panels of calligraphy.

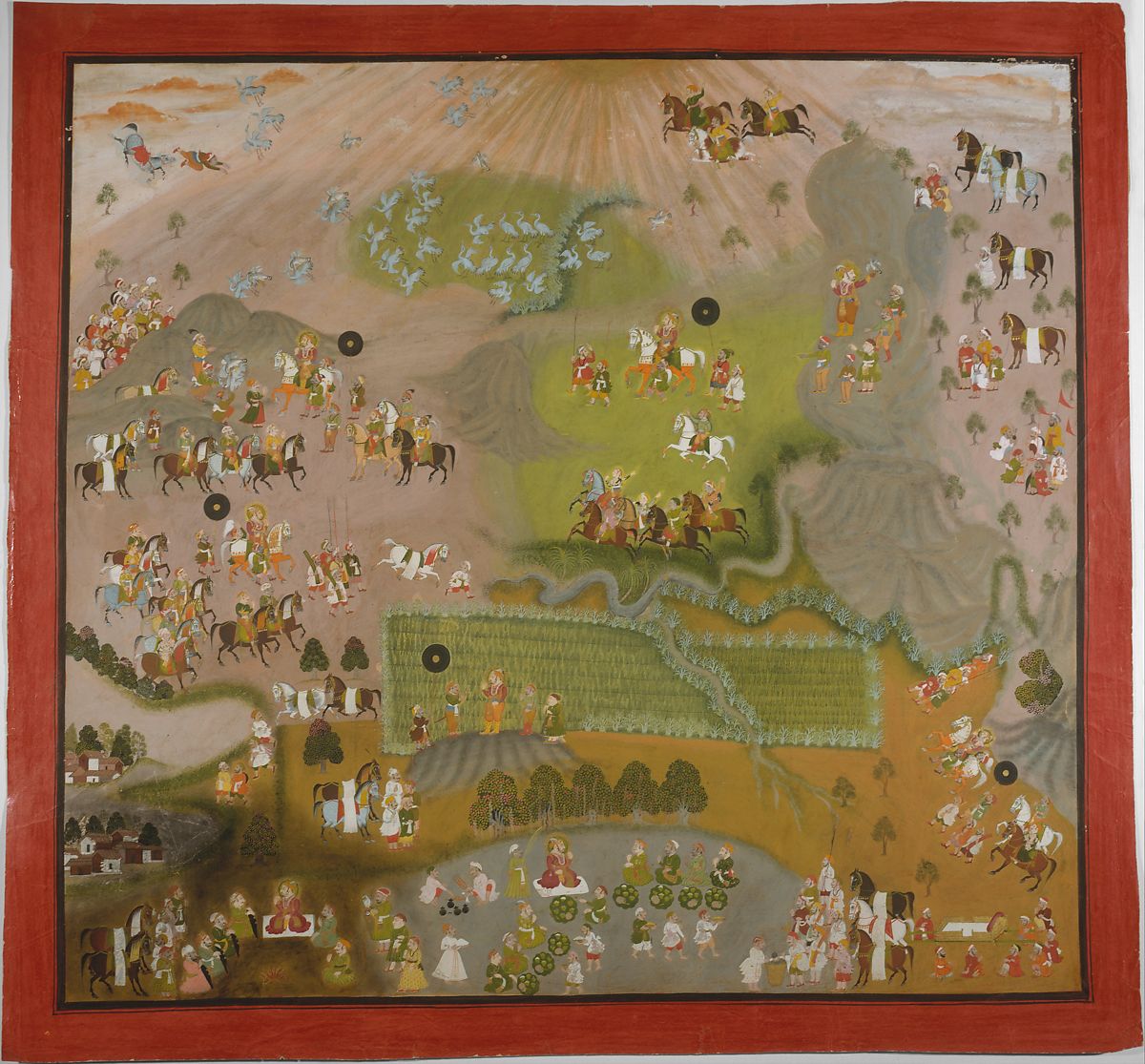

Rajput Art

As the Mughal still controlled many of the states, their art style was still found in Rajput paintings; however, the themes changed from the Mughal court images to depictions of epic events, landscapes, love, and the particular fondness for Lord Krishna and his activities. During this period, multiple schools and sub-schools were formed, each with different styles that reflected the events of the areas where they were located. The distinctive schools were associated with local rulers who influenced the artists; the many schools and sub-schools reflected the continual change of rulers. In each school, new techniques were developed with a wide variety of themes. With the absence of war, gardens, landscapes, poetry, music, and more peaceful scenes replaced artwork of military might.

Sensuality was an important part of Rajput art as depicted in mainly female figures. Clothing on women was transparent using sheer colorful fabrics, loosely draped with exposed midriffs. Their long limbs and doll-like features helped support the concepts of love, poetry, heroes, and heroines. Gold, reds, saffron, and purples brought energy and movement to the stories of the painters.

The Mewar school was conservative in style, painting with common motifs and bright colors and a flattened and monochromatic appearance of the scene. The royal hunting party (2.4.13) has an aerial and somewhat surreal view of the topography. Hills, valleys, streams, and the sun form the panoramic landscape with little dimension, and figures spread across different parts of the extensive site.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Maharana Jagat Singh Hawks for Cranes (1744, watercolor, ink, gold on paper, 68.3 x 75.5 cm) Public Domain

Marwar school artists focused on the themes of the nobles. The figures frequently were mechanical appearing and generally in profile. The two women (2.4.14) are conversing with another woman; all dressed in orange and red shades commonly used in Marwar paintings. The painting reflects the simple composition generally found in the different Marwar schools.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Ladies in a Pavillion (1640-1650, ink, watercolor on paper, 24.8 x 20.3 cm) Public Domain

Different styles were depicted in the Hadoti school, and generally, the themes were based on court scenes and the lives of the nobles. The colors were bright, and the figures looked natural in appearance. The raja (2.4.15) is sitting outside on the floral carpet while smoking his hookah. The saturated colors of the Rajput style are evident in the lower half of the painting, while the paler green of the background is similar to the color used in the Mughal style.

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): A Raja Smoking a Hookah (1690-1710, ink, watercolor, gold on paper, 15.9 x 11 cm) Public Domain

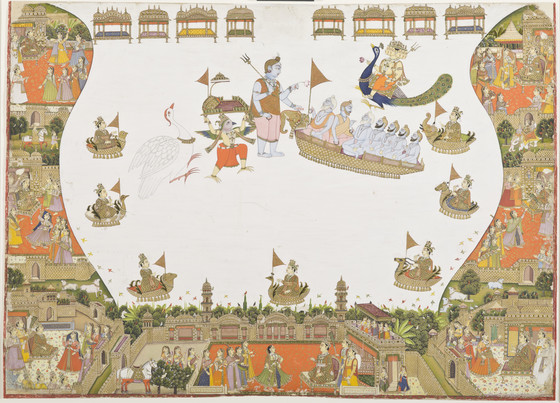

The different styles in the Dhundar schools all reflected the Mughal influence of color. Popular themes were religious, many following Krishna's life. The Perennial Performance in Paradise (2.4.16) is heavily painted with gold and the more muted colors of the Mughal yet reflects the Rajput interest with a broader subject matter and style of dress, landscape, and motifs.

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\): Perennial Performance in Paradise (watercolor and gold on paper, 57.15 x 79.69 cm) Public Domain

Krishna and Radha

Unlike Mughal paintings that depicted the elite, Rajput paintings were frequently about love, poetry, and music, particularly with images of Krishna and Radha. "What Chinese art achieved for landscape is here accomplished for human love… The lovers are always Radha and Krishna, typifying the eternal motif of man and woman and revealing, in everyday events, their heavenly image."[3] Their position and status were enhanced with the use of specific colors, dresses and jewelry. Krishna was usually dressed in yellow garments representing the passion of love. His skin was colored blue-gray, reflecting his journey from the sky, often holding a pink flower from the lotus plant in his hand to symbolize love.

Radha usually is portrayed in bright clothing and jewelry of pearls and emeralds. The sensuality of women was demonstrated with transparent fabrics for their gowns and headpieces. They wore long, flowing skirts of multiple colors leaving the midriffs uncovered. Pinks, reds, oranges, and purples were the favored colors, all ornamented with gold to produce a shimmering effect.

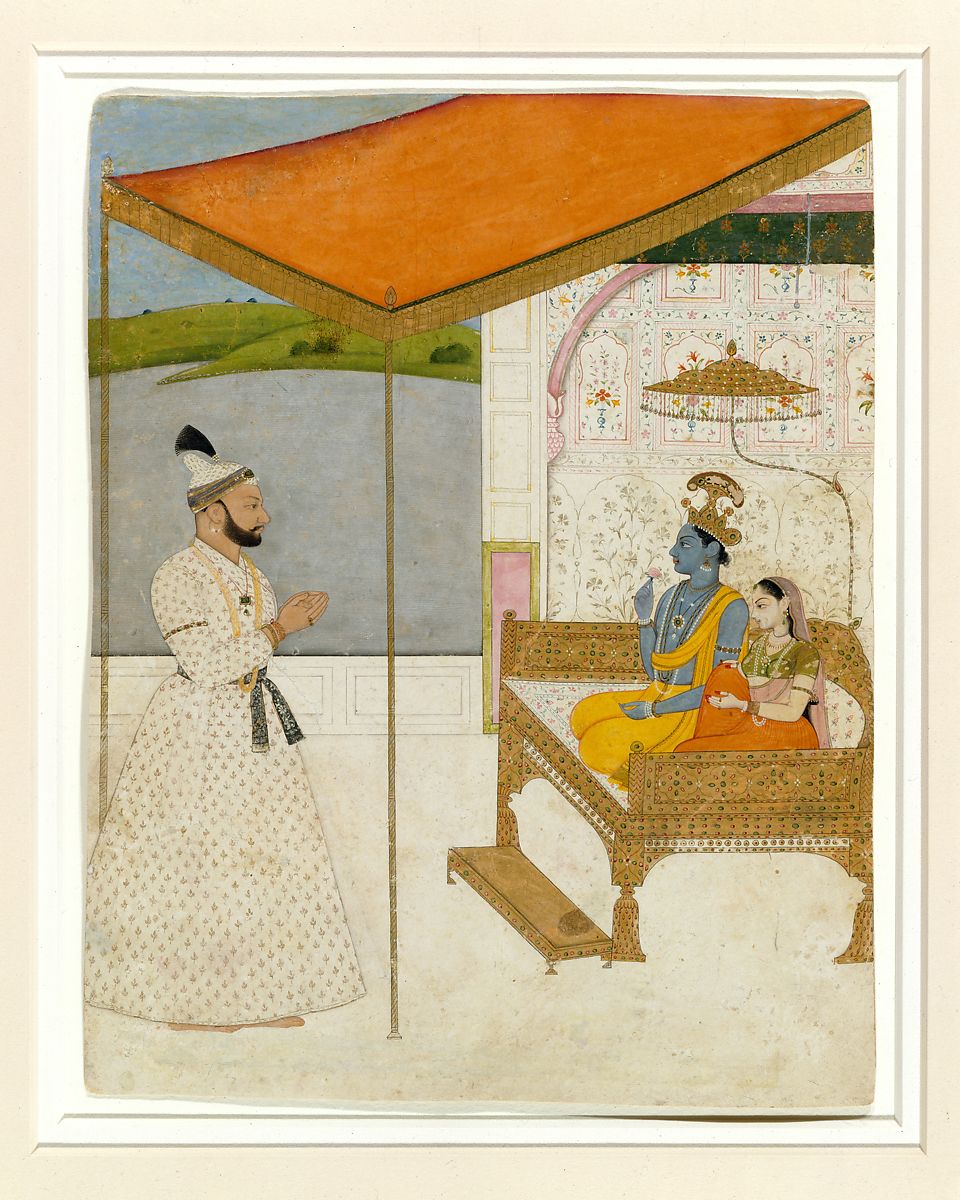

The painter Nainsukh created Raja Balwant Singh's Vision of Krishna and Radha (2.4.17), the raja looking at Krishna, hoping to receive his blessing. A bright orange canopy on the raja's terrace helps frame the images of Krishna and Radha, who are sitting on the golden throne. Unlike many other paintings, Nainsukh did not add all the background details usually found in the Rajput art; instead, he focused the scene on the meaning of the simpler spaces. Krishna and Radha are portrayed in their standard colors, dominating the right side of the image while the raja wears white and blends in with the rest of the background.

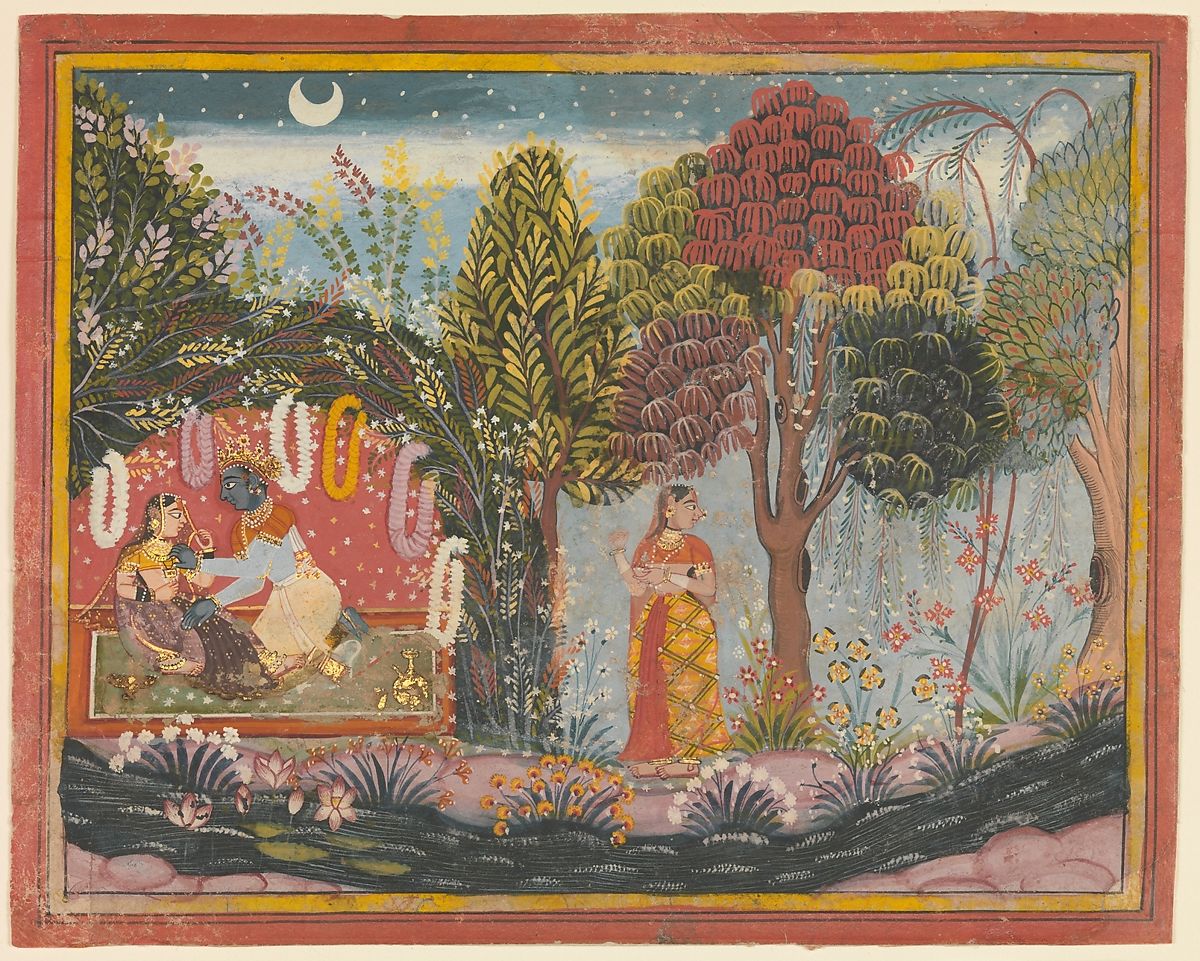

The image, Krishna and Radha in a Bower (2.4.18), is a page from the poetry of Gita Govinda, a visual form to illustrate the words describing the passion of Krishna and Radha, who are hidden deep in the bower. A companion of Radha stands guard under trees. Color is liberally used throughout the painting, yet the images of Krishna and Radha painted in their standard colors stand out against the bright orange background and green rug inside the bower. Under the trees, the gray background gives the feeling of a foggy, more secretive area.

Crying sounds of cuckoos, mating on mango shoots

Shaken as bees seek honey scents of opening buds…

By tasting the mood of lovers' union[4]

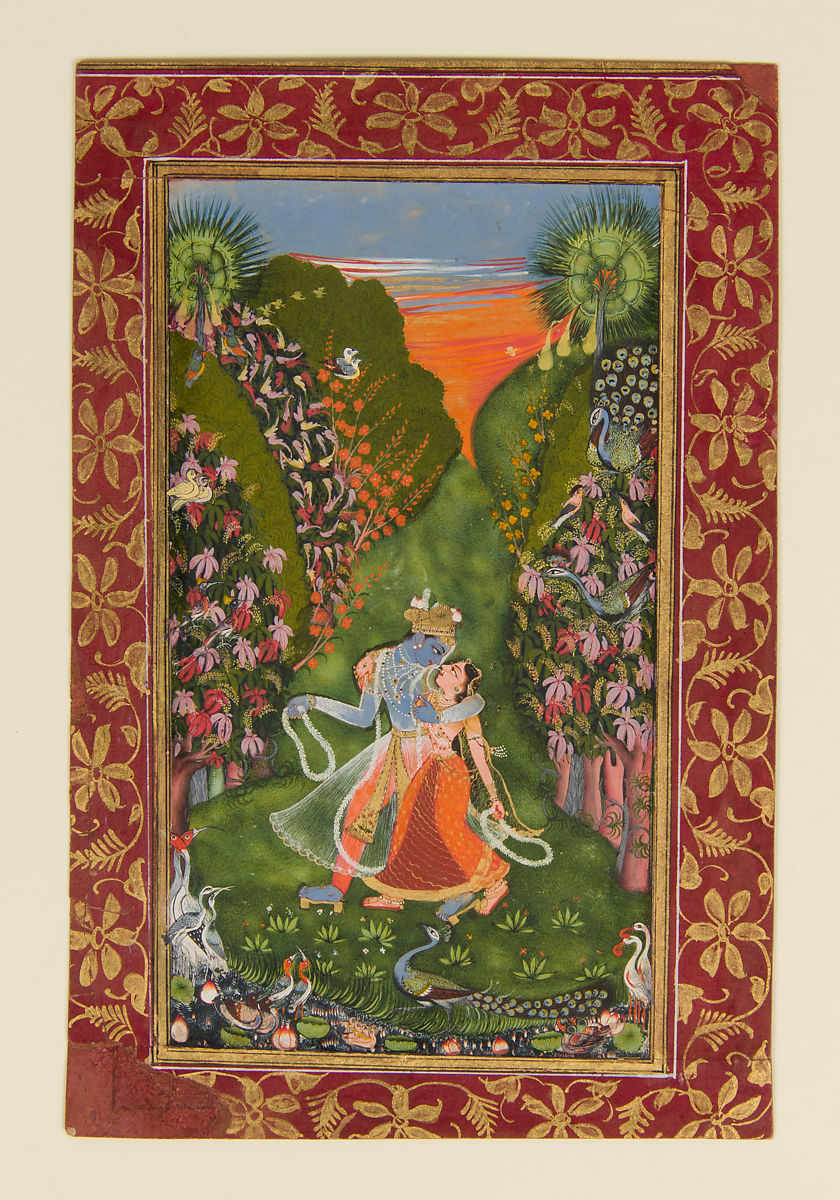

Radha and Krishna Walk in a Flowering Grove (2.4.19), alone during their walk, looking at each other. Illustrating a page from the Gita Govinda, love is found with the birds and trees and the intimate positioning of their bodies. This quintessential Indian idea—that nature echoes human passion—is beautifully manifested in this work by a master who has successfully translated emotion into a visual delight.[5] Krishna and Radha are centered in this painting, created in traditional colors. The orange of her dress compliments the orange of the sunset, giving movement along with the birds and flowering trees.

The emperors of the Mughal Empire were strong supporters of the arts and individual artists, encouraging them to study plants, animals, or people carefully. The court singly supported artists; individuals signed their names and multiple masters, and their styles are recognizable today.

[1]https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451263?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=ustad+mansur&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2

[2] Retrieved from https://www.rct.uk/collection/1005025/the-padshahnama. 1 January 2019.

[3] Agrawala, V. S., (2016). The Heritage of Indian Art A Pictorial Presentation, Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting.

[4] Gita Govinda (canto 3, verse 36). Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rajp/hd_rajp.htm. 16 January 2019

[5] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/65594?searchField=All&sortBy=relevance&ft=krishna+and+radha&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=15. 16 January 2019