2.3: Baroque (1600 – 1740)

- Page ID

- 120735

Introduction

After the Crusades, famines, and plagues of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance period brought new changes in the possibility of human invention and exploration. By the Baroque period, European societies were expanding, conquering other territories, and urbanizing their cities. The Italian towns acted more like states, led by wealthy merchant family associations and generally linked to the Papal establishment, both actively and lavishly funded artists with generous commissions. By the end of the 1500s, the revolt against the Catholic church's excesses and the upheaval from the success of Martin Luther establishing an alternative religious manifesto led to the Council of Trent by the Catholic church. The council defined new requirements, outlining forbidden books, building new churches, instituting austerity and piety within the church, and starting the Inquisition. The conflict between Protestant and Catholic factions led to turmoil and wars throughout Europe.

By the early 1600s, the Catholic church was reestablishing itself and wanted to rebuild Rome, its center, using pictorial and architectural visuals as grandeur pathways. Rome was built on the contours of Imperial Rome with haphazard expansion over the centuries. The pope wanted to change Rome and build new grand avenues, monuments, and churches. Throughout the 17rh century, new churches, fountains comparable to the Fountain of the Four Rivers, roads, paths became walks like the Spanish Steps, and remodeled buildings were part of the ambitious projects. Painters also brought a religious experience to their works; biblical stories brought alive, animated, and moving.

Baroque art reflected the social turmoil existing in Europe and the Catholic church's influence, stressing images of intense piety. Artists developed strong styles with dramatic colors, using the effects of light and theatrical physical poses. Baroque art is well-known for the artists who used the techniques of chiaroscuro and tenebrism, creating intense dark spaces punctuated by light features.

The Renaissance focused on classical symmetry, the central thrust of energy appearing in the center, a significant figure contrasted on the left and right. "The whole picture is so planned that the central figure has no counterpart but only favourable contrasts."[1] In Baroque art, contrast became radical; spatial symmetry is broken, becoming asymmetrical. The eye may start at the center and be compelled by the power of asymmetry, then forcefully moved to other sections of the overlapping, twisted figures. The faces of the figures displayed grandiose visions of rapture, bereavement, or mortality. Throughout the centuries, artists have used the concept of folded and draped material to create depth, light, and dark. "Yet the Baroque trait twists and turns its folds, pushing them to infinity, fold over fold, one upon the other. The Baroque folds unfurl all the way to infinity."[2]

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) was recognized as a prodigy when he was only eight years old and supported by his father, a sculptor. "Bernini's precocity earned him the favors of the mighty, who hailed him as 'the Michelangelo of his century."[3] He received many commissions early in his career from high-level church officials. Bernini was an avid Catholic, attending mass daily and believing, as described by the Council of Trent, that religious art should teach others and serve as publicity for the church; emotional and pious. His major patrons were the cardinals and popes, who commissioned Bernini to create fountains, tombs, sculptures, chapels, and his extensive work on Saint Peter's Basilica.

Historians believe the most remarkable example of Bernini's work is the Cornaro Chapel, commissioned by Cardinal Cornaro. Located in Rome at the Santa Maria della Vittoria church, the Ecstasy of St Teresa (2.3.1) was created for the transept in the small church. The scene was based on the ideals of Teresa of Avila, who entered the convent. She became known as a reformer, a mystic, and a woman of prayer and compassion. Bernini constructed the entire space as a complete theatrical installation, using the white marble of the centerpiece against the background of different colored marbles, a fresco on the ceiling, and recessed boxes on the sides holding the viewers. "The Cornaro chapel is, indeed, to be understood as a whole, not as merely its central focal point of the sculpture of Saint Teresa, but also taking into account the mural decorations, the illusionistic frescos on the value of the chapel, and the sculptural group of witnesses portraying some members of the Cornaro family. The whole combines different layers of reality and representation, which is overwhelming in its visual exuberance…"[4]

The sculpture of St. Teresa is positioned as the focal point. It represents a vision she described of an angel who descended holding a fiery arrow, piercing her heart with divine love. Bernini uses light from the top of the altar to shine on the cascading gilded rays on the sculpture's back and the elegantly folded and draped clothing creating deep surfaces and volume (2.3.2). The closeup of St. Teresa (2.3.2) displays the light and shadow Bernini achieved in the sculpted white marble. Bernini installed opera boxes containing marble members of the Cornaro family who are conversing or praying, seeming to be part of the theatrical scene before them.

Bernini installed opera boxes containing marble members of the Cornaro family who are conversing or praying, seeming to be part of the theatrical scene (2.3.3) before them.

The story of David in the bible was based on the concept if you believe you can achieve, the small David was hurling a rock and bringing oversized Goliath to the ground where David cut off his head. Made as a commission for Cardinal Borghese, Bernini's David (2.3.4) is the image of a person in motion, his body twisted, his face determined, the muscles in his legs taut. The statue is made from marble, a multi-dimensional work requesting the viewer to walk around and ensure all the action and movement in the figure is viewed. The deep draping of clothing, the stretched sinews of his muscles, or the position of the slingshot before release are dynamic. Bernini's son and his biographer both wrote about Bernini using the image of his face to create the face of David reporting when "Bernini was working on the self-image, Cardinal Maffeo Barberini…often came to the artist's studio and held the mirror for him. David's aquiline physiognomy and terrifying gaze correspond to Baldinucci's description of the artist."[5]

The Rape of Proserpina (2.3.5) demonstrates Bernini's ability to transform a block of Carrara marble into a dramatic scene about an unpleasant subject with unparalleled realism. The term rape meant kidnapping, the anguish on the woman's face evident. Abduction scenes were familiar in baroque art, and Bernini based his work on Proserpina, the daughter of Ceres and Jupiter, in a story by the Roman poet Ovid. Pluto. The god of the dead was enamored with the Proserpina and erupted from the earth in a chariot to abduct her. The bulging muscles of his legs and arms suggest the force he has to use to subdue Proserpina as she struggles, her body twisted in the visible battle, despair written on her face. The mastery of Bernini is dimensionally visible around the sculpture, the long curls of her hair, the dense curls of Pluto's beard, the detailed draping of the clothing, all developing deep shadows and light.

.jpg?revision=1)

One of the most compelling and dramatic parts of the sculpture (2.3.6) is the ability of Bernini to turn the hard, cold marble into the portrayal of soft skin as the powerful hand of Pluto grabs the thigh of the Proserpina, his fingers sinking into her skin.

Although Cardinal Borghese commissioned the sculpture of Apollo and Daphne (2.3.7), the theme was based on mythological stories instead of Catholic biblical scenes. The statue demonstrates Bernini's astonishing ability to create a life-like image from marble. The beautiful Daphne was the daughter of a river god who was denied by Cupid the ability to love men. Apollo was struck by Cupid's love arrow and overwhelmed by the beauty of Daphne, falling in love with her; however, she was not capable of love for him.

As Apollo pursues her, he is finally able to touch her, and at that point, she turns into a tree. Bernini captures the exact moment when Apollo lays his hand on her torso. She begins the transformation into a tree, reflecting Bernini's ability to represent Apollo's adoration and the rejection by Daphne. The images still appear to be moving, the arms and legs in motion. Their bodies are twisting in action, the sensuous placement of his hand. Her leg is beginning to turn into a tree trunk as her fingers become branches—all of the story seemingly captured in marble in one instant in time.

_(cropped).jpg?revision=1)

Saint Peter's Basilica, the heart of the Catholic church, was constructed during the Renaissance. The original beginnings of the church were built in the 4th century by Constantine the Great. Today the church is still known for pilgrimages and services by the pope. The vast interior of the basilica, constructed in a cruciform with an elongated nave, is dominated by the dome. One writer said, "Only gradually does it dawn upon us – as we watch people draw near to this or that monument, strangely they appear to shrink; they are, of course, dwarfed by the scale of everything in the building. This in its turn overwhelms us."[6]

From 1626, the pope designated Bernini as one of the foremost artists, a position he maintained for over fifty years and acknowledged as one of the greatest architects of the Baroque period. One of his early works was for the Baldacchino (2.3.8), a structure from the Middle Ages used to protect objects, a word derived from 'Baldacco,' a center in Baghdad for precious fabrics. Standing 28.74 meters high (about the height of a four-story building) and made of bronze, the Baldacchino formed a free-standing space around the altar and under the massive dome, a visual focus and a bridge between the scale of the basilica and humans.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): San Pietro, Baldacchino (1623-1634, bronze, 28.74 m) CC BY-SA 2.5

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): San Pietro, Baldacchino (1623-1634, bronze, 28.74 m) CC BY-SA 2.5 The four soaring helical columns were made of bronze, twisting as they rose, enhanced with leaves and bees curving to the top where a life-sized angel completed each column. The angels support the cap of an orb and cross, heightened with burnished gold (2.3.9). The draped canopy is also made from bronze and embellished with olive branches, images of people, bees, roses, and other vegetation, representing symbols of religion.

In the immense open space in front of Saint Peter's Basilica, Pope Alexander VII envisioned a spacious piazza, demonstrating the power and inspiration of the church. It was based on a design "so that the greatest number of people could see the Pope give his blessing, either from the middle of the façade of the church or from a window in the Vatican Palace."[7] The pope hired Bernini, who had been working on the inside of the basilica, to construct the grand piazza, eventually measuring 320 meters by 240 meters. For some events, the piazza held almost 300,000 people. A spiraling Egyptian obelisk was already positioned in the space, marking the center. Bernini surrounded the space with massive Doric columns (2.3.10) standing four deep and arranged in a trapezoidal shape instead of the usual round or square formation. Each column stood twenty meters high and 1.5 meters across.

To avoid the extensive space appearing as an overwhelming expanse of cobblestones (2.3.11), the cobblestones were arranged in a circular pattern, the obelisk marking noon. Although the entry roads have changed over the centuries, the major road presents a grand entrance into the plaza. At the time of Bernini, the streets were narrow and dark before viewing the magnificent piazza. Bernini wanted the pilgrims to reflect on the darkness of death before entering the open space of the piazza. He placed statues on top of the columns, symbols of those in heaven. Bernini and his assistants and students designed and constructed the 140 sculptures on top of the columns. Each marble statue was based on different martyrs, biblical characters, previous popes, or religious figures.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was born in the town of Caravaggio in northern Italy. At 21, he moved to Rome, the artistic center of Italy abounding with architectural marvels and paintings. His talent was recognized by Cardinal del Monte, who supported Caravaggio, introducing him to others and the opportunity for new commissions. His work was considered inventive, and compelling, and his audacious innovation in using light dramatically changed art history. Caravaggio's success propelled him to become one of the top-ranked painters early in his life, only to fall and become an outcast because of his unusual lifestyle and sometimes violent behavior resulting in multiple arrests, including murder. He used biblical and mythological stories of the past, painting them in the modern style of his time. Caravaggio focused on the poverty and spirituality of the biblical images, painting them in tattered clothing, an unkempt look against a background of other people dressed in contemporary clothing.

The Calling of Saint Matthew (2.3.12) and the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew (2.3.13) are two of Caravaggio's early paintings commissioned for Contarelli Chapel in the church San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. In 1600, both paintings illustrated biblical stories of St. Matthew and established Caravaggio as a master painter. He used light to create the sense of stopped action, with deeply shadowed non-reflective spaces and bright reflective areas illuminated by an unknown light source. The Saint Matthew paintings highly influenced younger artists, and many of them became Carvaggistis, taking the concepts to other countries. One influential art historian declared, "With the exception of Michelangelo, no other Italian painter exercised so great an influence."[8]

.jpg?revision=1)

In The Calling of Saint Matthew, Levi (2.3.13), the tax collector, is seated around the table and his aides as they count the money received from the day's work. Light suddenly illuminates their faces from the open door as Christ, pointing at Levi, and Saint Peter walks into the room; everyone froze in action. The dramatic diagonal of the line along the wall moves the viewer from the set of figures in contemporary clothing to the two shoeless figures in cloaks as the pointed arm of Christ moves the viewer back to the group. The window is covered, providing no direct light; Caravaggio uses the light from the door to reflect on the faces and lighter parts of their clothing, submerging much of the room in dark shadows. He also used red to highlight each person in strong opposition to the light and dark colors.

The biblical stories of St. Matthew end in the painting The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew. When the king of Ethiopia wanted to marry his niece, Saint Matthew would not allow the marriage. The king ordered Matthew killed. The scene is set against the dark interior by the baptismal pool with waiting converts assembled around the pool. The executioner stands in the middle, Matthew lying on the ground, his hand raised as though asking the executioner to stop. The angel hangs over the two men, reaching a palm branch to Matthew while the other figures appear to try escaping. Light seems to be coming from the side and scattered across the painting, emphasizing the jumble of bodies struggling to move away from the scene. The triangle of the executioner's left arm, Matthew's right arm, and the angel's arm form the triangular positions of light and depth. The figure far in the background is a self-portrait of Caravaggio as though watching the spectacle unfold.

Caravaggio based his painting of Narcissus (2.3.14) on Ovid's story in Metamorphosis, the young man who became enamored with his reflection, eventually dying from the desire for himself. Caravaggio used his image of the adolescent boy, well-dressed in stylish clothing, and bent over the pond to adore his likeness. The painting represents Caravaggio's regular use of chiaroscuro, the light source shining on the boy's selective parts, emphasizing tenebrism. The bottom half of the painting is bathed in darkness, the boy's reflection barely visible in the depth of the water; the dark, gloomy background surrounding the boy adds to the melancholy, hopeless feeling of the painting.

_edited.jpg?revision=1) Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Narcissus at the Source (1594-1596, oil on canvas, 110 x 92 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Narcissus at the Source (1594-1596, oil on canvas, 110 x 92 cm) Public Domain

The pope's treasurer-general commissioned the Crucifixion of Saint Peter for a reconstructed church in Rome as a companion piece on the altar of The Conversion of Saint Paul. Both Peter and Paul were considered the foundation disciples of the Catholic church and strongly connected to Rome and the papacy. The two paintings were positioned as devotional works surrounding one of the Virgin Mary. The first versions of the paintings were rejected, and Caravaggio painted the second versions. Although there is some confusion about what happened to each painting, most historians believe these two are the originals.

In The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (2.3.15), Caravaggio used the deep darkness of tenebrism to enunciate St. Peter as he is being crucified upside down, insisting on the unusual position, so he did not imitate the crucifixion of Jesus. Caravaggio places the others trying to lift the cross, their faces hidden, perhaps guilty about what they are about to do. Movement and drama are achieved using strong diagonal lines, the position of the cross, St. Peter, and one person in juxtaposition to the man under the cross as the other one forcefully pulled the rope. The colors are muted, the unknown light shining directly on St. Peter, displaying the anguish on his turned face away from the viewers, his hands bleeding, his body twisting. Caravaggio was a master of point-in-time images. The cross is partially up in the air, the others pushing and pulling, the movement apparent, yet in a few more minutes, St. Peter will be hanging upside down on the cross, dying.

.jpg?revision=1)

The Conversion of Saint Paul (2.3.16) illustrates Saul of Tarsus (renamed Paul) as a soldier on his way to destroy a Christian group. The painting is about a moment in time when Saul is blinded by light while hearing a voice. The other soldiers appear to be frightened by the light as they all turn in different directions reflecting the turmoil erupting in the scene. Caravaggio uses small reflective patches of light on other parts of the painting, defining the soldiers, giving them volume while the darkness pushes them into the background. Saul's horse in the middle of the scene is uncontrolled, and, in many paintings, it would be the focal point; here, the dark shadowy horse is recessed as the groom tries to control it. The blinding light shines solidly on Saul as he lies on the ground, his clothing beside him, his red robe helping define the body.

.jpg?revision=1)

Supper at Emmaus (2.3.17) is an example of Caravaggio's unique style; a theatrical display of a moment in time, a frozen, intense light counter-positioned to dark shadows. Ancient biblical figures are converted into familiar living humans with modern clothes, scrubby hair, or well-worn features. The painting portrays a biblical scene when Christ appears as an ordinary man to the followers. Only at the moment when he raises his hand to bless the bread do they recognize him. The standing innkeeper is not a believer and doesn't show any emotion as the two disciples instantly react; one man pushes back his chair as the other stretches out his arms in disbelief. None of the figures are idealized; dirt shows on their hands, some of the clothing is tattered, all exhibit the look of ordinary people. All of the food in the still life has religious symbolism supporting the values of the church.

Diego Velázquez

Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), born in Seville, Spain, studied art at an early age as an apprentice from a teacher who valued a broad education, including the classics and trends in literature and art. Velázquez's early works were based on bodegones; still life was based on activities in the kitchen or tavern. He used everyday people in ordinary clothing representing images based on religious stories, bringing him recognition for his ability to depict realistic scenes. His reputation in Seville earned an invitation to the court in Madrid as a painter of the royal family, remaining in the king's service for the rest of his life.

Although he mainly resided in Madrid, he did travel to Italy to study. On his second journey, he was the only painter who gained permission to paint the image of Pope Innocent X. One observer wrote, "Velázquez had come to Italy not to learn but to teach, for his Innocent X was the amazement of Rome. Every artist copied it and looked upon it as a miracle."[9] Most of his work was produced for the king and hung in royal houses, not accessible to ordinary people until after Napoleon's wars in 1814. His paintings were disseminated throughout Europe, creating an enormous impact on the art scene. His work did not have much influence during the Baroque period; a time focused on religious works as the primary theme. Velázquez did not paint many dramatic religious images; he spent the majority of his time on portraits or subtle yet complex allusions, as seen in Las Meninas.

His style of painting was almost photorealistic with accurate detail and distinctions while using loose brushstrokes. He was a master of the technique of chiaroscuro, bringing darkness or shadows and using light to emphasize critical perspectives and contrast areas. He frequently used multiple focal points, slashing diagonals, and different planes to move the viewer through the painting. One writer wrote, "Velázquez displaces the principal focal point of the picture, the king and queen, at whom everyone looks, but whose physical presence is dimly reflected in the mirror. In Las Meninas, the artist has created matchless optical effects, which only he could see, let alone render."[10]

In the painting Las Meninas (2.3.18), Velázquez depicts himself as an artist standing by the large canvas, yet he is not looking at the canvas or any potential subjects in the room. In the foreground, the immense dog lies by the dainty little person and the dwarf, forming one group. Another unit is the three females; the light focused on the golden-haired child in the center, a woman holding a tray, and one leaning inward. Deep in the shadows on the right side emerges a nun and a male who appeared to be having a conversation. On the back wall, the door to the room is open, and a man is silhouetted in the bright light from the open space. Next to him, another man and woman are reflected in the mirror. "What all these figures have in common is that they are all members of the royal household. In taking his place among them in the picture, Velázquez indicates that he too belongs to this exalted circle."[11]

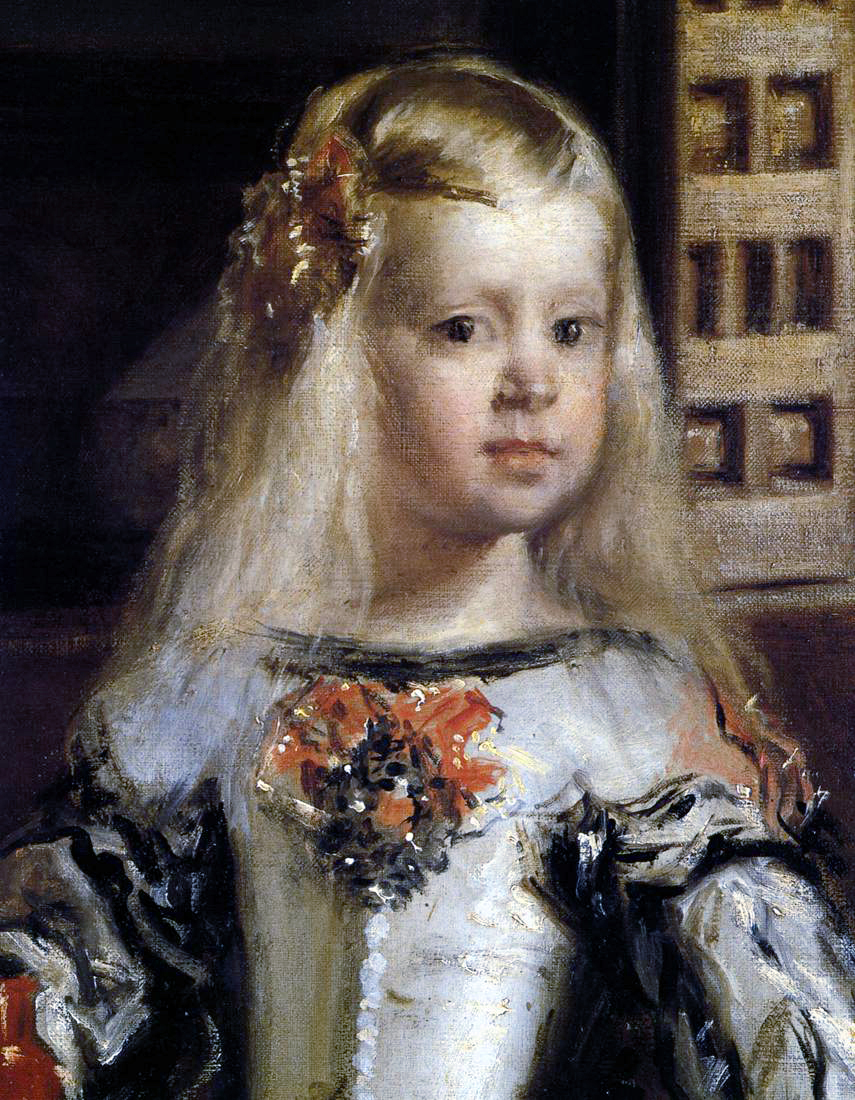

Las Meninas passes beyond the concept of paintings to resemble a person into ideas of illusionism with multiple meanings in one painting. The Infanta (2.3.19) stands in the middle of the painting; is she the focus?

The chamberlain José Nieto (2.3.20) stands in the open doorway, each foot on a different step. Was he entering the room or leaving?

The faces of Philip IV and his wife are reflected in the mirror (2.3.21). What is the perspective from where they are standing? What is missing from the painting?

And on one side (2.3.22), the artist himself stands in front of the immense canvas he is painting while the images he is supposedly painting are beside or behind him. Velázquez also used multiple light sources in the painting, adding various activities and illusions to the painting.

The Triumph of Bacchus (2.3.23) depicts Bacchus, the god of wine, and the allegory of releasing man from the pain of daily life, attending a drunken party. The scene is divided; Bacchus is topless, his pale skin highly illuminated in the painting, his robes loosely laying across his lap and legs. His face is idealized, not the look of the ordinary man, the nude satyr, and Bacchus depicting the world of mythical images. The other men live in the present; everyday and weathered clothing of the poor people liberated by wine from the day's suffering, demonstrating the artist's fondness to mix fables with the commonplace. Bacchus is crowning the kneeling man in the center as the seemingly intoxicated person in the background stares oddly out at the viewer, not part of the conversation. A bottle and pitcher sit at the feet of Bacchus, a still life similar to those earlier bodegon paintings of Velázquez.

.jpg?revision=1)

Velázquez painted Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan (2.3.24) after his trip to Italy. Critics view it as "one of his most successful compositions with regard to the unified, natural interaction of the figures."[12] The god Apollo, wearing the laurel crown, came to the foundry of Vulcan, the god of fire, informing Vulcan his wife Venus was having an affair with Mars, who was the god of war. Apollo appears as a god, wearing an orange toga, his head illuminated in light. Vulcan and his workers look like village blacksmiths, and all are positioned to reveal their muscular definitions. During his trip to Italy, Velázquez was influenced by Michelangelo's strong figures, and he incorporated the concepts into the workmen. As Apollo speaks, Velázquez demonstrates his ability to portray human emotion as the men react to the astonishing accusation. Vulcan stares at Apollo; one workman has his mouth open in disbelief, all of their bodies stopped, hearing this impossible message interrupting their work.

.jpg?revision=1)

During his second visit to Italy, Velázquez painted portraits of people in the pope's court. Though initially mistrustful about Velázquez's ability to create a proper persona, the pope allowed Innocent X's (2.3.25) image to be painted. One historian considered it "the masterpiece of all portraits" and said that "once seen, it is impossible to forget it.".[13] The pope is dressed in his white linen vestments, a sharp contrast with his red mozzetta, a summer version in red satin. The painting continually contrasts multiple variations of red and white, elegant and shiny, lacey and textured. The gold gild of the chair provided a frame for the ruddy face of Pope Innocent X, who is looking out at the viewer, a skeptical gaze on his face. Red can be a complex color to use, and painting with multiple shades and tones of red and avoiding vulgarity or garish conflicts is difficult. However, Velázquez turned distinctive reds with silk, velvet, and linen textures into rich, vibrant, refined paintings.

Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) was born in Rome, now recognized as the most influential female artist from the Baroque period and one of the most expressive artists of the era. Although few women were allowed to become professional artists at the time, her father recognized her abilities and taught her the skills of a painter. "By 1612, when she was not yet nineteen years old, her father could boast of her exemplary talents, claiming that in the profession of painting, which she practiced for three years, she had no peer."[14] Her father's painting based had been influenced by the style of Caravaggio, and Gentileschi also learned to work with deep dark colors and illuminated highlights. As her capabilities grew, her father hired the well-known painter Agostino Tassi to further her education. Unfortunately, she was raped by Tassi, who eventually was brought to trial on the charges, an emotionally difficult trial for Gentileschi. During the trial, they used thumbscrews on her to assure she was telling the truth. After a lengthy trial, Tassi was sentenced to eight months in jail. Many historians believe the rape and trial heavily influenced Gentileschi and how she painted.

Her father arranged her marriage a month after the trial. Gentileschi and her husband moved to Florence, where she became a successful painter, the first female allowed into the Accademia Delle Arti del Disegno. Instead of focusing on still life or portrait painting, she based most of her work on biblical or historical concepts. After success in Florence, Gentileschi moved back to Rome, successfully painting portraits yet not receiving any profitable commissions based on altarpieces. She also spent time in England, working with other artists who recognized her talents. Critics throughout modern times have written about the incredible talent of Gentileschi; how her female subjects were powerful, rebellious, not timid or weak, her brushwork to be strong and bold, not hesitant, an artist who fought the prejudices against women with determination and courage. She excelled in the use of tenebrism, contrasting the dark recesses and light areas.

Susanna and the Elders (2.3.26) was painted in 1610 when Gentileschi was sixteen, a subject painted by other male painters as a classical myth with elaborate settings, attempting to seduce a young girl. However, she treated the subject matter differently, the older men as voyeurs, the horizontal stone wall as the only barrier to a possible sexual assault, the visceral emotions evident. She painted the girl anatomically correctly with "unflattering details of a woman's body: pendant breast, groin wrinkle, crow's foot wrinkles on her neck and at the top of her right arm, and awkwardly positioned legs."[15] The scene is stark with only the blue sky and bench as background, the two men hovering over the wall, the fear apparent on her face as she tried to escape. The painting waS completed before her rape by Tassi, however, some historians believe Gentileschi may have been harassed earlier. The painting reflects her distress; however, no evidence exists about her feelings at the time.

%252C_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg?revision=1)

When women seldom held outside, paid jobs, Gentileschi painted herself in Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (2.3.27), portraying herself as a vigorous and muscular woman, a powerful person, holding a brush instead of a sword; presenting herself as the metaphor of painting. Yet, she still displayed principles of the female persona, including the draped golden necklace, unruly locks of hair symbolizing divine frenzy of an artistic temperament, and drappo congiante, garments with changing colors alluding to the painter's skills.[16] She had been invited to the British court by Charles I and painted her self-portrait there. Her arm creates a strong diagonal line in the composition, the fore-shortened arm bringing a three-dimensional feeling. She appears to be looking at the unknown light source illuminating her face instead of the canvas she is painting. The texture of her silky dress, disheveled hair, shiny necklace, and smudged hands demonstrates her ability to bring realism to the work.

_-_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg?revision=1)

In her Self-Portrait as a Lute Player (2.3.28), Gentileschi pictures herself similarly to her other portrait. Lute players were familiar characters found in Baroque paintings. It is believed the painting was a commission for Cosimo II de Medici when she was in Florence. Her clothing reflects the trends of the area with the turban, gold embroidery, and sumptuous fabric. Her face is illuminated on one side, enhancing her determined look of strength and capability.

Judith and Her Maidservant (2.3.29) demonstrate the influence of Caravaggio's techniques of tenebrism. This painting is a sequel to her work illustrating the moment Judith slays Holofernes. In this work, the maidservant is taking the severed head of Holofernes, wrapping it in a bag as Judith, with a knife in her hand, keeps watch, perhaps hearing a noise as they both appear to hesitate. Gentileschi dramatically uses chiaroscuro techniques, the glow from a candle lighting both women's faces and the front of Judith's golden dress. The deep, dark background of the crimson curtain formed the stage to bring the figures to life in the forefront. The high contrast of the tenebrism from the limited light against the darkness creates drama and tension.

Peter Paul Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) was born in Germany and moved to the Netherlands as a child, where he began training as an artist. He went to Italy to study the Renaissance artist and then to Spain, where his early works incorporated classical techniques. In 1608, as his mother was dying, Rubens returned to Antwerp, where he remained and was appointed a court painter. He was very successful as an artist, had a large studio, taught students, and had many assistants helping complete his extensive portfolio of commissions, unusual and exceptionally large images. Rubens was also a diplomat and represented Isabella for the Spanish Netherlands, traveling to France and England to negotiate. Because Rubens was an artist with a friendly personality, he traveled without suspicion and carried diplomatic secrets to the different countries. He was described as "having a tall stature, a stately bearing, with a regularly shaped face, rosy cheeks, chestnut brown hair, sparkling eyes but with passion restrained, a laughing air, gentle and courteous."[17]

Rubens was a prolific artist completing over 1400 paintings. His work was in the Flemish Baroque style, generally based on religious figures in large altarpieces or diplomatic figures connected to mythical gods and goddesses. Rubens was probably most known for his voluptuous nude female figures. The women were frequently middle-aged, buxom with generous curves. Although his work is part of the Baroque style, he did not focus on Caravaggio's single light source and deep darkness. He painted figures in multiple positions with numerous diagonal lines, each figure anatomically correct, either nude or wearing intricate, textured clothing. He used the juxtaposition of strong lights across the scene against darkness, adding to the drama.

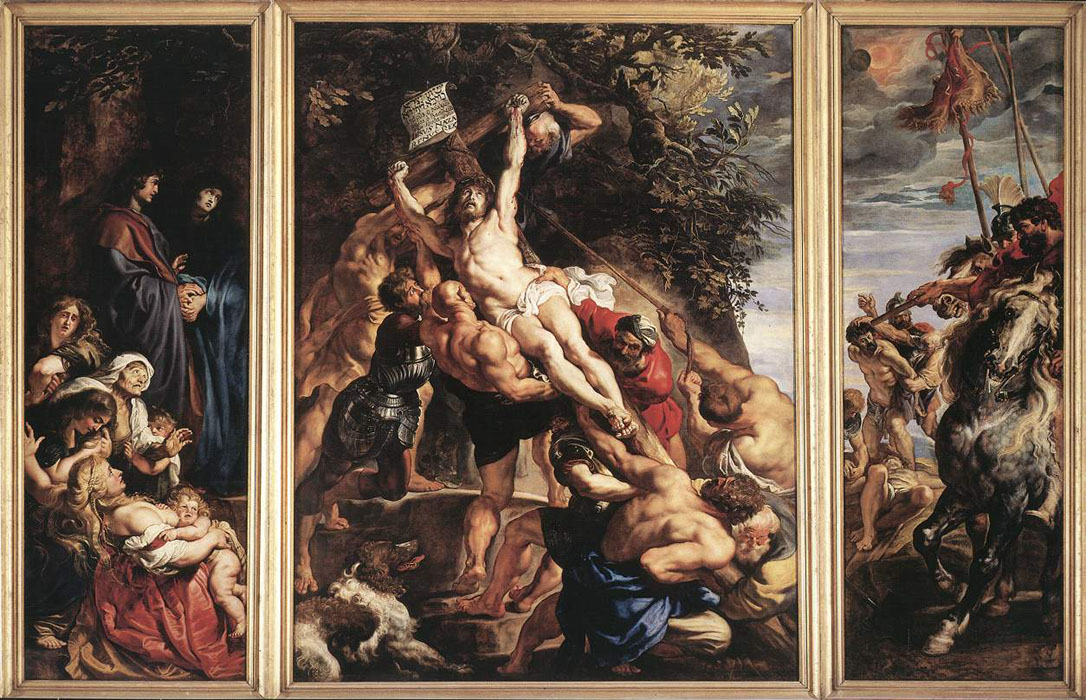

Elevation of the Cross (2.3.30) was a commission as an altarpiece for St. Walpurgis. Unlike the usual triptych with the Madonna and child portrayed on the center panel, Rubens changed the center to depict the crucifixion. The strain on the men is evident in their muscular bodies as they struggle with the weight; the diagonal position of the cross and foreshortening of the body of Christ demonstrate movement and tension. Mary and St. John watch with the other mourners in the left panel. On the right panel, a Roman soldier astride his horse waits with the two thieves who will also be crucified. Rubens used a brilliant light shining on the figure of Christ to create the focal point on the triptych. The figure is raised higher than the center point bringing the viewer to look toward the heavens. The bodies of the people are each formed into different positions, demonstrating Ruben's knowledge of anatomy. Rubens used some of his assistants to help complete the immense work. First, he made a modello, a small oil sketch as a model. With live, prepositioned models, he fashioned drawings of each figure used as the basis for the large triptych. When the assistants completed the essential work, Rubens completed the work.

In The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (2.3.31), Rubens disguises a brutal scene with an idealized exemplification. The painting illustrates the story of twins Castor and Pollux, who abducted the two daughters of the king of Leucippus, Phoebe and Hilaeira. The painting was considered innovative, a combination of Renaissance, Baroque and Flemish styles. The balanced composition begins at the bottom. Both the captor and captive have their feet side by side, the painting flowing upward through the struggling voluptuous figures of the two women, their bodies moving in different diagonals. The pale, light skin of the captives is in strong contrast to the darker hirsute men. The horses contrast with each other, facing opposite directions, the dark horse under control as the gray horse rears up, out of control. Even the violence of the abduction is juxtaposed against the soft blue sky and rolling countryside. Rubens used vigorous brushstrokes to apply the concentrated colors of the draped clothing.

Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\): The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (1617-1618, oil on canvas, 224 x 210.5 cm) Public Domain

Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\): The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (1617-1618, oil on canvas, 224 x 210.5 cm) Public Domain

Maria de Medici was the daughter of Francis de Medici of Tuscany, who lived from 1575 to 1642. Her first marriage in 1600 to King Henry IV by proxy was an elegant affair complete with entertainment and sumptuous dining. Maria was bringing Medici wealth to shore up the French government, and "her dowry amounted to 600,000 gold scudos, sufficient to wipe out more than half of France's national debt, with the promise of 20,000 more a year thereafter."[18] She was the second wife of Henry, with whom she had five children during a tumultuous marriage and continual fights the many mistresses of Henry. Their oldest son was Louis XIII, and in 1610 when Henry was assassinated, Marie became the Regent Queen of France, ruling until her son was of age. Her relationship with her son was turbulent, and she had to flee the country until she was finally reconciled late in her life.

She wanted to build a new palace, vast and spectacular. Peter Paul Rubens received the commission to create twenty-four paintings to embellish the walls. The works were based on her life cycle from birth to when she reconciled with her son. Rubens started the project in 1622, creating twenty-one paintings about Marie and her life and three of Marie and her parents. The contractual agreement specified that Rubens had to paint each figure, a daunting task since each painting included multiple people; he assumed he used assistants to work on the basic structures and details. Portraits of the Marie de Medici cycle (2.3.32) now hang in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The stories in each painting were divided into childhood, life as a queen, and when she was the regent. Rubens added images of allegorical and mythological figures to fill the painting with additional interest and meaning. "Exploiting to the utmost the allusive and malleable potential of pictorial allegory, the artist appears to have used his large and eclectic group of figures to stage several levels of meaning at once, from the factual to the fantastic."[19]

When the ruler of a country was seeking a new bride, he frequently had an artist paint the person's image to decide if the woman was suitable in looks. Henry IV gets his first view of a potential wife in the painting, The Presentation of Marie de Medici's Portrait to Henry IV (2.3.33). Rubens surrounds the portrait with the gods of myth looking down as though to demonstrate their approval. The symbol of France stands behind Henry to support his choice, a classical image; draped green fabric, Roman boots, and exposed breasts.

In Arrival for Disembarkation of Marie de Medici at Marseilles (2.3.34), Rubens took a dull concept and made it glamorous. Marie is walking down the gangplank held by gods of the sea to meet the representation of France, who is wearing the blue cape and the fleur-de-lis, a heavenly golden angel blowing the trumpet. Rubens brings the beauty of heaven and earth, realism and allegory into view. On these and the other paintings in the set, Rubens uses strong diagonals to position the figures, some in elegant textual clothing and others the voluptuous figures of Rubens style. Red prevails throughout the paintings as accent areas, bare skin provides illumination, gold displays the ornamentation, and the dark recesses bring deep contrast.

The Consequences of War (2.3.35) was representative of Ruben's thoughts of the Thirty Years War that raged across Europe from 1618 to 1648, a conflict between Catholics and Protestants and their supporting governments clashing for political power. The war caused much devastation, famine, and disease. The painting is considered one of the finest Rubens examples of his Flemish Baroque style, a combination of transformed Baroque and Renaissance elements. He included his unique style of the female form as well as well-formed and muscular men. Mars, the god of war, in the center with his helmet and red cape. Venus, the goddess of love, tries to constrain Mars, her face pleading with him to stop, small cupids assisting her. On the ground lay papers and books, the arts destroyed by the ravages of war. Rubens uses multiple diagonal positions by the figures to bring movement and conflict to the painting, focusing on how color is applied with light and darker shadows.

Nicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) was born in France, trained there, and lived in Paris before moving to Rome, where he spent most of his time. Early in life, he studied ancient writers and artists, developing paintings reflecting their influence. Most of his early work was based on commissions for private clients, not immense altarpieces. At age thirty, he moved to Rome, then still regarded as the artistic center in Europe. The wealthy patrons' demand for smaller paintings to hang in private homes created a favorable business environment for artists. Poussin struggled at first and was seriously ill from syphilis. After he recovered, he received a commission from the Vatican, and the work established his standing as a significant artist. Afterward, he no longer accepted commissions for monumental paintings and concentrated on requests to paint and create in his style based on allegorical and religious images.

In his letters, Poussin wrote he liked to pursue art similar to the way Greeks wrote music, in singular modes with individual moods based on diverse contexts. He wanted his paintings to be designed and implemented based on the subject, an intellectual balance alongside the poetry of meaning, or as historians have written, the 'Theory of the Modes,' a painting had an underlying text, a literary source as a base for an artistic muse. "His erudition is more textual than pictorial; surveying the literature, one gets the distinct impression that he is studied more in the library than the museum."[20] In 1641 he was persuaded to return to France, painted several large commissions, was asked to adorn the ceilings of the Grand Gallery in the Louvre, design tapestries, and paint allegorical works for the cardinal. Poussin became decidedly hopeless; too many commissions, criticisms from multiple sources, and continual palace intrigues, and he returned to Rome in 1642. In Rome, most of his religious supporters were gone, and he turned to wealthy patrons who were more flexible as he combined the stories of mythology and literature with landscapes and classical architecture.

Poussin painted Et in Arcadia Ego (2.3.36) in 1637-38, and idealized scene, each shepherd, carefully positioned around a tomb. The term is translated as "Even in Arcadia, there am I," Arcadia the utopian land and the I as death. Arcadia was located in a mountainous area of Greece and was idealized as a paradise by the poet Virgil. Poussin contrasted the concept of an idyllic setting with the idea of death as visualized in the tomb. One shepherd is tracing the letters on the tomb, stating that death is even found in blissful Arcadia. A well-dressed female stands and seems to know about the engraving, possibly she represents an allegorical figure. Poussin minimized movement in his figures; each figure seemingly posed in position, a more classical style. The sky reflects his classic blue color as storm clouds move across, punctuated by the dark, vertical trees.

.jpg?revision=1)

Poussin choreographed his landscapes very carefully, balancing each element against another, whether a large boulder positioned by a stream or the verticality of a tree. He precisely painted the leaves and bark of trees or shrubs. In the background, he used the specific blue of a bright sky with clouds in the background or an ominously dark sky. Landscape with Saint John on Patmos (2.3.37) depicts St. John living on the Greek island where he was writing, seated in the old ruins. The setting is idealized; an obelisk and temple remains, centered in the background, with column fragments perfectly positioned in the foreground. Poussin used his trademark blue color for the sky, the sun reflecting on the gray clouds and intensely dark contrasting trees. Everything is harmoniously positioned in the painting; a new world generated from the ruins of the past.

The Baroque style swept through Europe, influencing art, music, and literature; elaborate and dramatic. The Baroque period began in Rome and spread throughout other European countries. Paintings brought drama, deep contrasts of light and dark, spiritual and mythological; sculptures were dynamic, twisted, elaborate, grand, sumptuous, and expansive architecture. The ideals were to impact and inspire the viewer, bringing renewed religious vigor through excessive boundaries of art and architecture.

[1] Brown, M. (1982). The Classic Is the Baroque: On the Principle of Wölfflin's Art History. Critical Inquiry, 9(2), 379-404. Retrieved April 3, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1343327

[2] Coppens, J. (2012). Folding Mutants or Crumbling Hybrids?: Of Looking Baroque in Contemporary Theatre and Performance. In Vanderbeeken R., Stalpaert C., Depestel D., & Debackere B. (Eds.), Bastard or Playmate?: Adapting Theatre, Mutating Media and Contemporary Performing Arts (pp. 90-101). Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wp64r.9

[3] Posèq, A. (1990). BERNINI'S SELF-PORTRAITS AS DAVID. Source: Notes in the History of Art, 9(4), 14-22. Retrieved April 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23202667

[4] Coppens, J. (2012). Folding Mutants or Crumbling Hybrids?: Of Looking Baroque in Contemporary Theatre and Performance. In Vanderbeeken R., Stalpaert C., Depestel D., & Debackere B. (Eds.), Bastard or Playmate?: Adapting Theatre, Mutating Media and Contemporary Performing Arts (pp. 90-101). Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wp64r.9

[5] Posèq, A. (1990). BERNINI'S SELF-PORTRAITS AS DAVID. Source: Notes in the History of Art, 9(4), 14-22. Retrieved April 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23202667

[6] Masson, G. (2001). The Companion Guide to Rome. Companion Guides. Pp 615-616. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Peter%27s_Basilica

[7] Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Peter%27s_Square. March, 2020.

[8] Ward, T. (2016). The Guardian of Mercy: How an Extraordinary Painting by Caravaggio Changed an Ordinary Life Today. Skyhorse.

[9] Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/vela/hd_vela.htm (10 April 2020).

[10] Brown, J. (1982). Velázquez and the Evolution of High Baroque Painting in Madrid. Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, 41(2), 4-11. doi:10.2307/3774662

[11] Kahr, M. (1975). Velázquez and Las Meninas. The Art Bulletin,57(2), 225-246. doi:10.2307/3049372

[12] Retrieved from https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/vulcans-forge/84a0240d-b41a-404d-8433-6e4e2efd21ab%20(13

(13 April 2020)

[13] Retrieved from https://www.doriapamphilj.it/portfolio/velazquez/ (14 April 2020).

[14] Garrard, M. (1989). Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art. Princeton University Press, p. 13.

[15] Slap, J. (1985). Artemisia Gentileschi: Further Notes. American Imago, 42(3), 335-342. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/26304021

[16] Garrard, M. (1980). Artemisia Gentileschi's Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting. The Art Bulletin, 62(1), 97-112. doi:10.2307/3049963

[17] Retrieved from https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/peter-paul-rubens (16 April 2020)

[18] Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/30/arts/marie-frances-florentine-queen.html

[19] Cohen, S. (2003). Rubens's France: Gender and Personification in the Marie de Médicis Cycle. The Art Bulletin, 85(3), 490-522. doi:10.2307/3177384

[20] Neer, R. (2006). Poussin and the Ethics of Imitation. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 51/52, 297-344. Retrieved April 20, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25609498

[21] Mann, J. (1997). CARAVAGGIO AND ARTEMISIA: TESTING THE LIMITS OF CARAVAGGISM. Studies in Iconography, 18, 161-185. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23924073