2.4: Arrival of Europeans in the Indian Ocean

- Page ID

- 154801

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Arrival of Europeans in the Indian Ocean

Hanging over this whole discussion of the 15th-century Indian Ocean was what would occur at the end of that century. In 1498, three Portuguese ships led by Vasco da Gama would arrive in the Indian Ocean. Eventually landing in Calicut (see Figure 2.4.1), Da Gama initially received the hospitality of the local ruler known as the Zamorin. The Portuguese had come a long way, but some of the first people they met in the city were Muslim merchants from the North African city of Tunis who, to the astonishment of Da Gama and his men, spoke to them in Castilian. It is a reminder that while this represented new terrain for European Christians, the availability of land/sea routes through the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf meant that Muslims from the Mediterranean had long had access to India. To the Portuguese, the city contained wealth beyond their greatest hopes. One chronicler observed that its markets contained:

…all the spices, drugs, nutmegs, and other things that can be desired, all kinds of precious stones, pearls and seed-pearls, musk, sanders, aguila, fine dishes of earthenware, lacquer, gilded coffers, and all the fine things of China, gold, amber, wax, ivory, fine and coarse cotton goods, both white and dyed of many colors, much raw and twisted silk, stuffs of silk and gold, cloth of gold, cloth of tissue, grain, scarlets, silk carpets, copper, quicksilver, vermilion, alum, coral, rose-water, and all kinds of conserves.

Eventually tensions would grow between the Portuguese and their hosts and after a three-month stay, Da Gama’s fleet of ships fled the city and began what would be a long tortuous journey home. Although a huge navigational success, in other ways this initial voyage represented an inauspicious start for the Portuguese. They experienced humiliations, were expelled from multiple cities, and ultimately showed themselves to be too uncouth, too violent, too prejudiced, and too poor to fit neatly into, what was for them, a more sophisticated trading context. For all the difficulties of that initial voyage, however, it was in the end wildly profitable. As a result, subsequent fleets would set out from Portugal beginning almost immediately upon Da Gama’s return. Rather than trying to fit themselves into a trading world that exposed their own limitations, on these later voyages, the Portuguese would instead lean into their advantages. One of these was the presence of cannons onboard their ships that could be used in both naval warfare and for the bombardment of coastal cities. However, just as significant as this technological and tactical innovation was the Portuguese introduction of what was essentially a state-based and militarized trade into a trading system that had been plenty competitive but rarely grounded in violence. On his 2nd voyage in 1503, Da Gama demonstrated the Portuguese willingness to perpetrate extreme violence in pursuit of their interests. While crossing the Arabian Sea, his fleet encountered a large Arab ship carrying nearly 400 Muslim pilgrims from Mecca back to Calicut. After a four-day pursuit, Da Gama finally caught up with the ship and to the horror of the scribe Tomé Lopes: “the Admiral ordered the ship burnt with the men who were on it, very cruelly and without the slightest pity.”

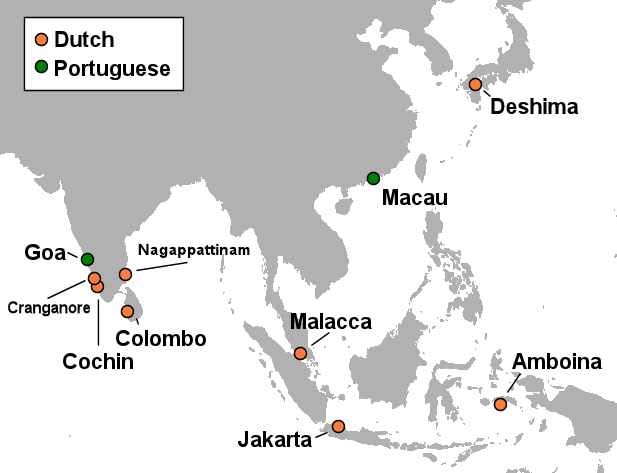

Through savvy politics, intimidation, and exemplary violence the Portuguese were able to seize several ports ranging from the Mozambique Channel in East Africa to Malacca at the opposite end of the Indian Ocean (see Figure 2.4.2). In addition, under an agreement with Ming China, they were allowed to establish a base on the island of Macao at the mouth of the Pearl River in southern China. We tend to identify these far-flung ports and bases as the Portuguese Empire, but the Portuguese themselves referred to their collection of territories in Asia as the estado da India. This empire was at the same time an impressive achievement for a kingdom of barely more than a million people while also being less than it seemed. Certainly, the Portuguese were able to create a key role for themselves in the Indian Ocean world and in doing so made Portugal a major world power. However, their empire as well as later European maritime powers like the Dutch and English offer a lesson about the difference between pretensions and reality.

To a greater or lesser extent, the goal of these empires was to establish a monopoly on the most valuable goods that circulated in the Eastern seas. That could literally mean controlling the world’s supply of nutmeg -- which at the height of its value in the mid-17th century was worth more per ounce than gold in European markets -- as the Dutch attempted, or, like the Portuguese, simply controlling the sea lanes upon which those goods were carried. However, it turned out that the seas were too large for the Portuguese to fully patrol and nutmeg seeds too small for the Dutch to keep them from being smuggled to areas outside of their control. Thus, for all the power and wealth such empires were able to accumulate they were not able to fundamentally change the nature of trade in the Indian Ocean.

In political terms, the Portuguese found that claiming territory was easier than holding onto it. By the latter 16th century, they had been expelled from many of their early holdings by resurgent Asian states or, at least, made to feel much more vulnerable in others. In one example from 1587, a Portuguese captain named Jeronimo de Quadros felt the need to petition the King of Portugal in hopes of receiving aid for his tiny Persian Gulf outpost called Comorao (see source below). De Quadros reported that it was only due to his efforts that, “the fort …had not fallen, despite daily attacks, [only] because of the defense by the petitioner, at great risk of personal loss.” In addition to paying and feeding the soldiers and mercenaries who defended the fort out of his own pocket, he also had to provide “bows, strings, opium, and other necessary costs,” not to mention the frequent need to maintain the mud walls of Comorao which melted away when the summer monsoon brought rain up from the Arabian Sea. No record of a reply to this petition exists and while Jeronimo’s fate is unknown, Comorao certainly succumbed to the power of the Safavid Empire before the century was out. (See primary source 2.4.1)

An even greater example of the reassertion of power by Asian states can be found in Japan. From the 1530’s the Portuguese had run a highly profitable arbitrage business carrying silver from Japan, where it was produced and therefore cheap, to Ming China, where it was in high demand and thus expensive. Among other things, the great profits from this trade would help finance the Portuguese missionary efforts that always accompanied their commercial activities. While there were early hopes that Catholic missionaries would find success in India or China, Japan turned out to be the one region where significant numbers of conversions occurred. In fact, by the late 16th century missionary efforts had been rewarded with the conversion of hundreds of thousands of Japanese Christians. However, as the Japanese islands became increasingly unified over that century, the new leadership came to see Christianization as a threat to its ambitions. As early as 1587, the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi promulgated an edict declaring that “Japan is the country of gods, but has been receiving false teachings from Christian countries. This cannot be tolerated any further.” Over the next half century, the issue of Japanese Christians and European missionaries would continue to vex the state until finally in 1635 the Portuguese would be formally expelled from Japan, any missionaries who attempted to remain would be executed, and Japanese Christians would be forced to renounce their faith or suffer the consequences. Many Catholic missionaries were martyred as a result of this policy and over the next few years Japanese Christianity would be driven completely underground. Still desiring foreign trade, however, the recently established Tokugawa Shogunate permitted Dutch merchants to trade at the single port of Deshima based on the understanding that they would not make any attempt to propagate their Faith among the Japanese. As this example demonstrates, far from being dominant, Europeans often found it necessary to bow to the whims of their hosts if they wished to continue their activities across Asia.

European expectations in the Indian Ocean also clashed with reality in more intimate settings. Until the 19th century, very few European women traveled to Asia. That meant that if the male migrants, most of whom stayed for many years if not their entire lives, wanted to marry they would have to find a wife from among the local population. Such marriages seemed to be mutually advantageous. For Europeans, the chance to access the connections, local knowledge, and capital of their wife’s family would provide them an opportunity to make the kind of private fortune that their relatively meager salaries could never provide. For the local family, having a European ally was a great way to protect their trading interests. Despite the theoretical benefits of such couplings, European men were often left frustrated by their wife’s refusal to conform to European standards of behavior. Unlike in Europe, in Southeast Asia, it was very common for women to be lead actors in long-distance trade. Indeed, daughters in merchant families were educated to calculate and make profits. More generally, women were accustomed to a level of autonomy that seemed shocking to their European husbands. The letters that Dutchmen sent home frequently expressed frustration over how hard it was to “tame” their wives. Their lack of commitment to monogamy was the most scandalous aspect of this, but for men who assumed that if their wives were rich then they would be too, they were similarly shocked at how little access they had to that wealth. These were savvy businesswomen who never assumed that marriage meant that they should sacrifice their economic autonomy. They, rather than their husbands, would continue to control their wealth and property. The Dutch ultimately waged a centuries-long and only partially successful war aimed at taming these unruly women. There is evidence that later generations began to conform more closely to European sexual mores, but despite the imposition of a more intrusive and all-encompassing capitalist world system dominated by European companies and their Chinese and Indian merchant allies – virtually all of whom were male – women continued to play a substantial, if shrinking, role in Indian Ocean trade well into the 20th century.

All of this is another reminder that modern world history must be able to acknowledge the growing reach and significance of Europeans in the centuries leading up to the modern age without using that growing prominence as a justification to erase or diminish non-European actors. There would come a time when the global power of a few major states in Europe and North America would become virtually uncontested, but that time had not yet arrived by the 17th century.

A declaration follows by the scribe Nuno Martins that on 8 April 1587, in the city of Ormuz, in his lodgings, a petition was presented by Jeronimo de Quadros, captain of the bandel and fortress of Comorao, with a subscription [despacho] of the Senhor Captain Joao Gomes da Silva, as follows:

In the petition, Jeronimo de Quadros stated that Joao de Quadros, his father, was appointed to the captaincy of the fort and bandel of Comorao by the King in acknowledgment of his services, which extended over eight or nine years prior to his death; he died leaving many debts which his estate was insufficient to pay; Jeronimo succeeded him in the captaincy, in which he had now served for seven years, and in the first three years the Estudo da India was at war with the King of Lar, who had captured the forts of Tazerque, Xamell and Maurequim, with all their lands and appurtenances and those of the bandel of Comorao. The fort of Comorao had not fallen, despite daily attacks, because of the defence by the petitioner, at great risk of personal loss. The petitioner asked for evidence on these points to be taken from certain witnesses and in particular for the following questions to be put to them:

Whether as a result of the capture of his lands by the captain of the King of Lar he had lost revenues and received no revenues from previously productive properties, and from his own resources maintained the soldiers he had in the fort; and he had for a long time kept a garrison of 45 men, whereas the crown only paid him an allowance for 25; and during the three years of war he had, at his own expense, maintained 50 native troops without receiving any revenues from the bandel. Whether for most of the time, until the present, there had been a state of war with the King of Lar and on many occasions the latter's captain, Reis Cambar, had raided as far as the fort of Comorao which had often been relieved by troops from Ormuz, whom Jeronimo had fed at his own expense, spending much of his wealth. Whether as a result of the wars the bandel of Comorao and its lands were depopulated and wasted and that the revenues would not subsequently attain half their former levels, even in peace. Whether as a result of the wars that had occurred in one way or another, it was necessary, for the defence of the fort, to maintain at least 25 soldiers in it, which the petitioner did at his own expense and whether he undertook many repairs to the fort at his own expense. Whether for these reasons the petitioner was very poor and in debt, through having spent all he had in maintaining the fort. Whether he had at all times to guard the fort 15 Portuguese soldiers whom he fed at all times and who were paid [by the crown] only for garrison duty in Ormuz. Whether to defend the surrounding lands he had normally 30 native soldiers [solldados mouros] and sometimes 45 whose [wage] he paid, and when they went to accompany the cafellas [a caravan] or in pursuit of bandits and raiders, he provided their maintenance, bows, strings, [opium] and other necessary costs. Whether, because the fort was of mud, it required continued upkeep and whether one of the outworks [baluartes] needed to be rebuilt every year at the petitioner's expense, without any help. Whether it was necessary for him to send tribute or presents [saguates] to neighbouring native chiefs [mouros vezinhos] so that they should refrain from raiding, which he did at his own expense, and without which they would conduct raids openly.

The petition closed with the request that evidence on these points be taken and recorded in a carta testemunhavel.

Discussion Questions:

- What types of challenges did De Quadros face at Comorao?

- What do these challenges reveal about the nature of Portuguese imperialism in the Indian Ocean?

- What advantages allowed the Portuguese to establish themselves in the Indian Ocean?

- To what extent did the arrival of Europeans represent a major change to the Indian Ocean?