2: Global Interactions - 1450-1650

- Page ID

- 147158

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Understand globalization as a process that intensified up to 1650 CE

- Examine diverse world regions of the world up to 1650 CE

- Identify the nature and intensity of cross-cultural interactions within and among world regions up to 1650 CE

- Recognize emerging global trends by 1650 CE

- How did early globalization affect the world between 1450 and 1650?

- Which elements of the world of 1450-1650 seem most familiar to you? Which seem most different?

Introduction

…the Europeans didn’t invent globalization. They changed and augmented what was already there. If globalization hadn’t yet begun, Europeans wouldn’t have been able to penetrate so many regions so quickly. – Valerie Hansen (Hansen, 5)

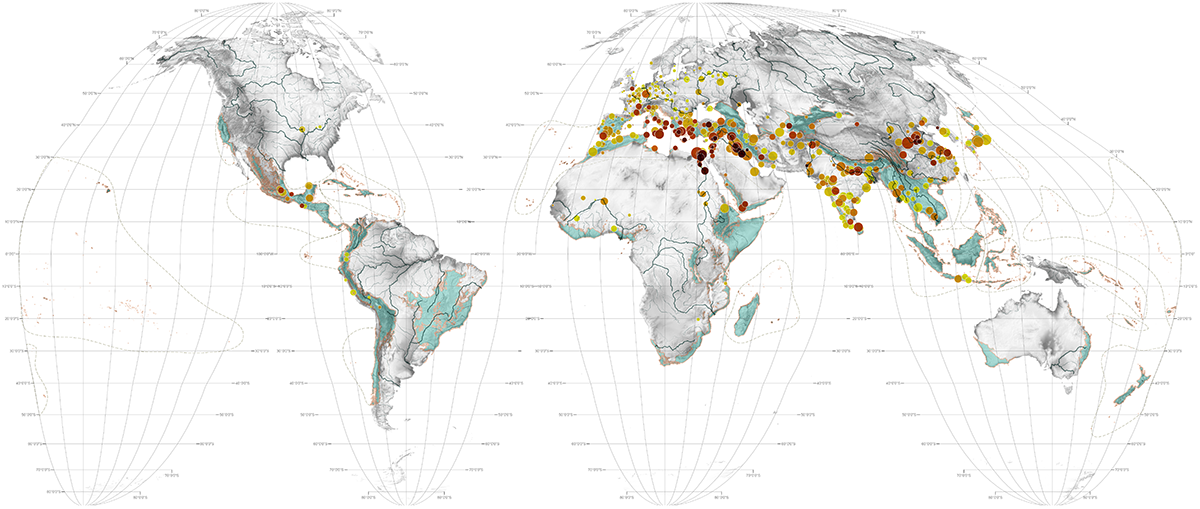

We begin our exploration of modern world history in the 15th century. From the perspective of those alive during that century there was little to suggest radical changes were brewing. From the privileged position of the present, however, we can see that a series of small and large events and processes, some connected and some not, would create cumulative effects that would help transform the human experience. It was a time in which a larger segment of the global population than ever was integrated into a still loose, but fairly robust system of interaction and exchange that stretched across large portions of Afro-Eurasia. Even within this connected world many, if not most, people could continue to live their lives unaware of or unaffected by the existence of this system. Yet, many others living in what the historian Janet Abu-Lughod has called “an archipelago of cities,” built livelihoods based on the existence of large-scale networks of interaction. These networks shifted more than goods around this world. Along with the textiles, spices, metals, animal products, and enslaved people also moved knowledge and information, techniques and technology, and styles and foodstuffs while also inspiring new desires and new ambitions. In cities like Timbuktu, Bruges, Alexandria, Jeddah, Aden, Calicut, Malindi, Malacca, Samarkand, or Hangzhou residents survived, and even thrived, by engaging with this system. Instead of a single world system, the world was a collection of individual systems that were indirectly linked together. The map shows the places where the systems overlapped, allowing for the spread of goods, people, technology, and ideas to spread among areas that did not directly interact (see map in Figure 2.1).

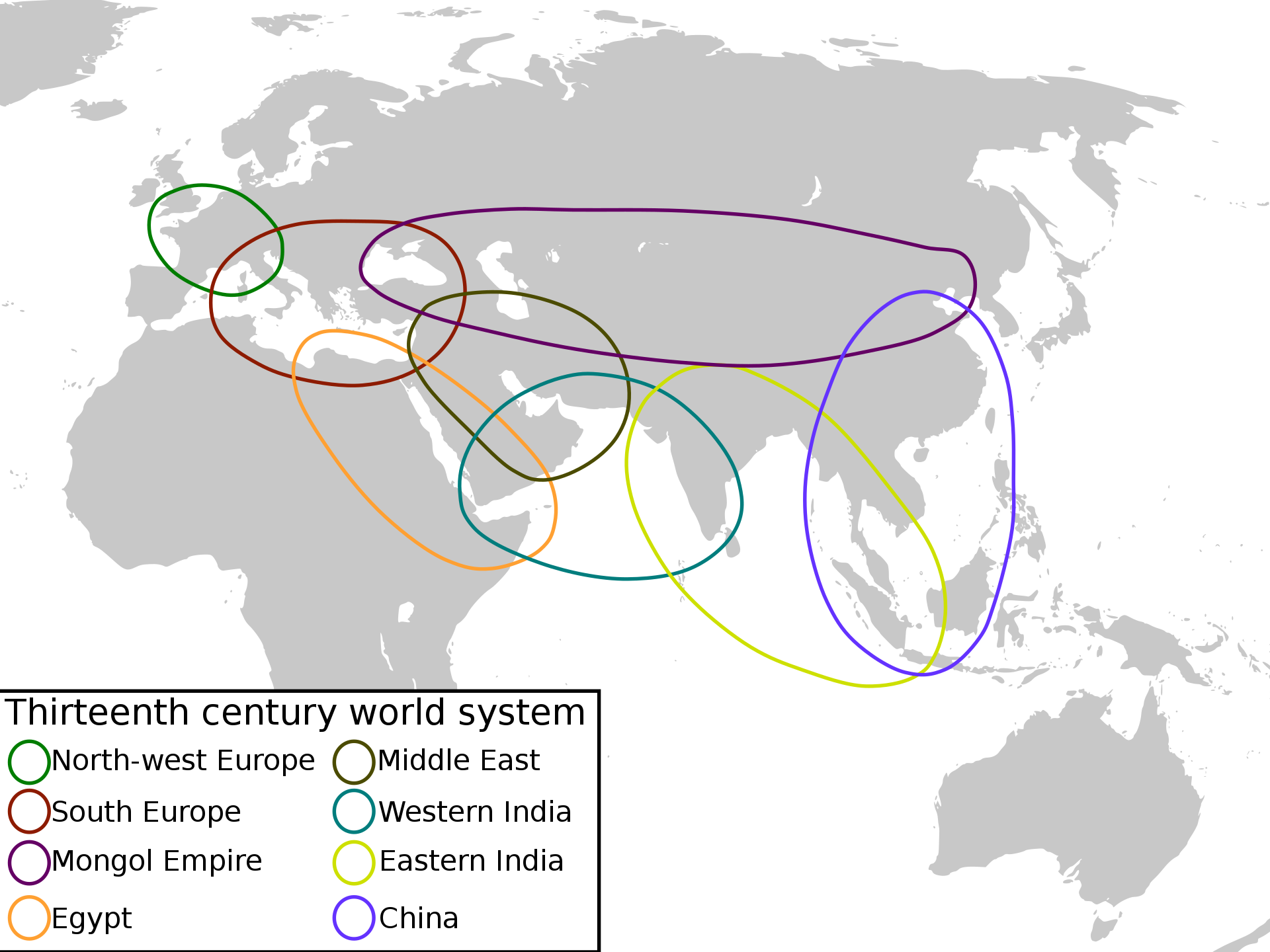

Figure 2.1 is a map of Afro-Eurasia that describes the system of world trade in the thirteenth century. Essentially there were three large transcontinental commercial circuits, namely European, Middle Eastern, and Asian. The European network linked the areas along the Atlantic Coast with many parts of the Mediterranean. The Middle Eastern network linked the areas between the eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. The Asian network connected the Indian subcontinent with China and SE Asia. These 3 large networks are subdivided into smaller regional networks. Thus a total of 8 regional networks are shown using ovals in the map. Over the next roughly two and a half centuries, the system would only grow, and its impact would intensify, such that by 1650 CE it had become truly global. With the development of new sea routes across the Atlantic, the Pacific, and between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, direct exchange was established among all the populated continents save Australia. As a result of these new connections, the list of global cities could be expanded to include emergent European colonial settlements in the Americas including Potosí, Acapulco, Bridgetown, and Boston; major ports in East, Southeast, and South Asia like Deshima, Macao, Batavia, and Surat; and new imperial capitals such as Lisbon, Madrid, Istanbul, Isfahan, and Agra (see Figure 2.2).

The process by which the world became tied together is complex. On the one hand, it was driven by imperial politics of conquest, domination, incorporation, accommodation, and exploitation. At the same time, it was also propelled by the efforts of smaller states which saw in the seas the potential to satisfy their ambitions for greater wealth and power. Lastly, an increasingly assertive merchant class – serving themselves, their family or clans, investors, or the state itself – helped tie together all these strands into a single system. In this chapter we will explore a world on the cusp of massive change; a world that was beginning to be defined by globalization.

Thumbnail: "Chinese woodblock print, representing Zheng He's ships," in the Public Domain.

- 2.1: Early Modern Globalization

- Early modern globalization was a complex process with a transformative impact on the world. In the Americas indigenous societies were defined by complexity and change rather than simplicity and timelessness.

- 2.2: State Building in West Africa

- West Africa was home to significant urban centers most of which were self-ruled city-states. The process of state-building began before the advent of Islam in the region, but the adoption of the Faith first among the merchants and then by the political elites was crucial in providing these states with a set of useful skills and connections with which to expand their power. Islam first arrived in the region with Muslim merchants who took part in the trans-Saharan trade.

- 2.3: Trade and Interaction in the Indian Ocean

- While the interactions between Europe and the Americas became most intensive after 1492, this section explores trade and cross-cultural interactions within the Indian Ocean World prior to the arrival of Europeans.

- 2.4: Arrival of Europeans in the Indian Ocean

- Modern world history must be able to acknowledge the growing reach and significance of Europeans in the centuries leading up to the modern age without using that growing prominence as a justification to erase or diminish non-European actors. This section examines change and continuity in the Indian Ocean after the first arrival of European ships in 1498.

- 2.5: China in the Gloal Economy

- The most famous period of the early Ming began with the 1403 decision of the Yongle Emperor to order the outfitting of an enormous fleet of ships to sail into the Indian Ocean. This chapter describes the rise of Ming China and their treasure fleets.

- 2.6: Silver and the Ming Dynasty

- The voyages of Zheng He had an unintended consequence whose impact would be global. This section emphasizes the role of internal changes in the Ming Dynasty in helping to create a silver-based global economy based.

- 2.7: Empires and Globalization

- The period from 1450-1700 saw the emergence of some of the most influential empires in human history. These empires helped establish identities, traditions, cultures, and connections that would live on well past their lifespans. This section looks at the effect of empires on the process of globalization by examining aspects of the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires.

- 2.8: Chapter Summary and Key Terms

- Globalization was intensifying as a result of increased trade, imperial expansion, and cross-oceanic travel and the result was a more integrated world in which more and more people had become tied together into a global web of interactions. At the same time, this was a world that was still very different than the one that would emerge with the coming of modernity.