18.8: The Incas

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 264091

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Architecture of the Inca

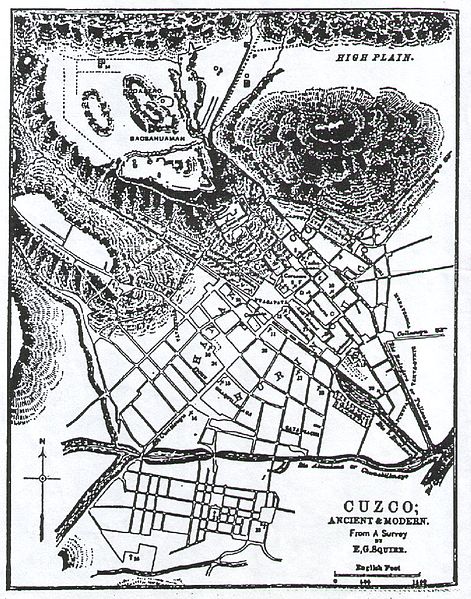

The Inca capital city of Cusco is one of the finest examples of both traditional Inca and colonial architecture.

Learning Objectives

Describe the important architectural sights of the Incan Empire

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Kingdom of Cuzco was a small city-state of the Inca empire that served as the preeminent center of politics and religion.

- In 1535, the Spanish explorer Pizarro sacked much of the Inca city and built a new city over pre-colonial foundations.

- Because of its antiquity and importance, the center of the city retains many buildings, plazas, and streets from both pre-colonial and colonial times. These include the Temple of the Sun, the Cathedral of Santo Domingo, and the Plaza de Armas.

- Inca architecture is widely known for its fine masonry, which features precisely cut and shaped stones closely fitted without mortar (“dry”).

- Machu Picchu is a 15th century Inca citadel situated on a mountain ridge near the city of Cusco; it is believed to have been built as an estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti (1438–1472).

Key Terms

- plateresque: Pertaining to an ornate style of architecture of 16th century Spain suggestive of silver plate.

- antiquity: Ancient times; former ages; times long since past.

Background: The Inca Empire

The Inca Empire was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century, and the administrative, political, and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. Its last stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572.

Incan architecture is the most significant pre-Columbian architecture in South America. The Incas inherited an architectural legacy from Tiwanaku, founded in the 2nd century BCE in present-day Bolivia. The capital of the Inca empire, Cusco, still contains many fine examples of Inca architecture, although many walls of Inca masonry have been incorporated into Spanish Colonial structures. The famous royal estate of Machu Picchu is a surviving example of Inca architecture; other significant sites include Saksaywaman and Ollantaytambo. The Incas also developed an extensive road system spanning most of the western length of the continent.

The City of Cusco

The Kingdom of Cusco was a small city-state in the Inca empire. Scholars have established that the Inca did not occupy the area—previously inhabited by the indigenous people of the Killke culture—until after 1200 CE, under the leadership of Manco Cápac. The Inca empire was divided into four suyus (regions) that met at the capital of Cuzco, which served as the preeminent center of politics and religion. The Inca created the city of Cuzco in the shape of a puma, a shape still visible in modern aerial photographs.

Pizarro, the Spanish explorer and conquistador, sacked much of the city in 1535 during the Spanish invasion and built a new city over pre-colonial foundations. Because of its antiquity and importance, the center of the city retains many buildings, plazas, and streets from both pre-colonial and colonial periods. Remains of the Palace of the Incas, the Temple of the Sun, and the Temple of the Virgins of the Sun still stand. In some cases, the Inca buildings and foundations have proved to be stronger than the foundations built in present-day Peru.

Characteristics of Inca Architecture

Inca architecture is widely known for its fine masonry, which features precisely cut and shaped stones closely fitted without mortar (“dry”). However, despite this fame, most Inca buildings were actually made out of fieldstones or semi-worked stone blocks and dirt set in mortar; adobe walls were also quite common, usually laid over stone foundations. The material used in Inca buildings depended on the region; for instance, in the coast they used large rectangular adobe blocks, while in the Andes they used local stones.

The most common shape in Inca architecture was the rectangular building without any internal walls and roofed with wooden beams and thatch. There were several variations of this basic design, including gabled roofs, rooms with one or two of the long sides opened, and rooms that shared a long wall. Rectangular buildings were used for quite different functions in almost all Inca buildings, from humble houses to palaces and temples. Even so, there are some examples of curved walls on Inca buildings, mostly in regions outside the central area of the empire. Two-story buildings were infrequent; when they were built, the second floor was accessed from the outside via a stairway or high terrain rather than from the first floor. Wall apertures—including doors, niches, and windows—usually had a trapezoidal shape; they could be fitted with double or triple jambs as a form of ornamentation. Other kinds of decoration were scarce; some walls were painted or adorned with metal plaques, and in rare cases walls were sculpted with small animals or geometric patterns.

The most common composite form in Inca architecture was the kancha, a rectangular enclosure housing three or more rectangular buildings placed symmetrically around a central courtyard. Kancha units served widely different purposes as they formed the basis of simple dwellings as well as of temples and palaces; furthermore, several kancha could be grouped together to form blocks in Inca settlements. A testimony of the importance of these compounds in Inca architecture is that the central part of the Inca capital of Cusco consisted of large kancha, including Qurikancha and the Inca palaces. The best preserved examples of kancha are found at Ollantaytambo, an Inca settlement located along the Urubamba River.

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu is a 15th century Inca citadel situated on a mountain ridge 7,970 feet above sea level. It is located in the Cusco region above the Sacred Valley, which is 50 miles northwest of Cuzco. Most archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was built as an estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti (1438–1472). Often mistakenly referred to as the “Lost City of the Incas” (a title more accurately applied to Vilcabamba), it is the most familiar icon of Inca civilization. The Incas built the estate around 1450 but abandoned it a century later at the time of the Spanish Conquest. Although known locally, it was not known to the Spanish during the colonial period and remained unknown to the outside world until American historian Hiram Bingham brought it to international attention in 1911.

Machu Picchu was built in the classical Inca style, with polished dry-stone walls. Its three primary structures are the Inti Watana, the Temple of the Sun, and the Room of the Three Windows. Most of the outlying buildings have been reconstructed in order to give tourists a better idea of how they originally appeared.

The site is roughly divided into an urban sector and an agricultural sector, and into an upper town and a lower town. The temples are in the upper town, while the warehouses are in the lower. The architecture is adapted to the mountains: approximately 200 buildings are arranged on wide parallel terraces around an east-west central square, and the various compounds are long and narrow in order to exploit the terrain. Sophisticated channeling systems provided irrigation for the fields. Stone stairways set in the walls allowed access to the different levels across the site. The eastern section of the city is thought to have been residential, and the western section, separated by the square, is believed to have been for religious and ceremonial purposes. This western section contains the Torreón, a massive tower which may have been used as an observatory.

Spanish Architecture After the Conquest

After the conquest and the destruction of the city of Cusco, the Spanish built new structures over much of the Inca architecture. Some of the most noteworthy architectural sights in Cusco include the following:

- The Coricancha (“Golden Temple” or “Temple of the Sun,” named for the gold plates covering its walls) was the most important sanctuary dedicated to the Inti (the Sun God) during the Inca Empire. Over the foundation of the Coricancha, Spanish colonists built the Convent of Santo Domingo in the Renaissance style. The Convent exceeds the height of many other buildings in the city.

- The Barrio de San Blas neighborhood includes houses built over Incan foundations, along with the oldest parish church in Cuzco. The church, built in 1563, houses a carved wooden pulpit that is considered the epitome of colonial era woodwork in the city.

- The Convent and Church of la Mercad, founded in 1536, was a Spanish complex that was destroyed in an earthquake in 1650 and rebuilt in 1675. Modeling the Baroque Renaissance style, it contains choir stalls, paintings, and wood carvings from the colonial era.

- The Spanish Cathedral of Santo Domingo was built in phases between 1539 and 1664 on the foundations of the Inca Palace of Viracocha. The cathedral presents late-Gothic, Baroque, and Plateresque interiors. It also has a strong example of colonial goldwork and wood carving. It is well known for a Cusco School painting of the Last Supper depicting Jesus and the 12 apostles feasting on guinea pig, a traditional Andean delicacy.

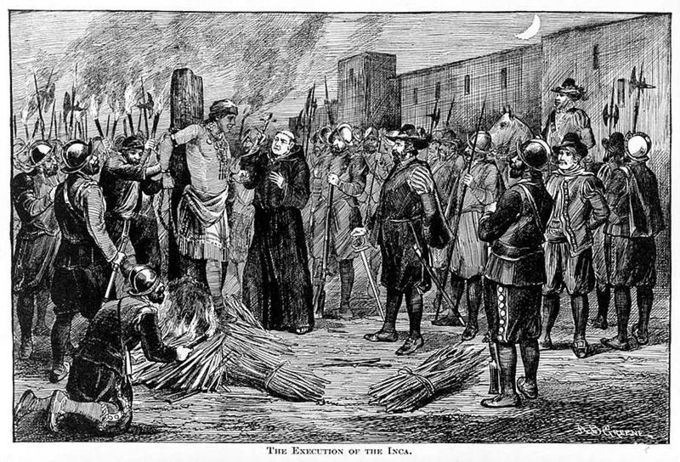

- The Plaza de Armas, known as the “Square of the Warrior” in the Inca era, has been the scene of several important events in the history of this city, such as Pizarro’s proclamation of conquest over the city and the scene of the death of Túpac Amaru II, the indigenous leader of the resistance. The Spanish built stone arcades around the plaza that endure to this day.

- La Iglesia de la Compaña de Jesus was built by the Jesuits over the foundations of the palace of the Inca ruler Huayna Capac. It is considered one of the best examples of the colonial baroque style in the Americas. Its façade is carved in stone, and its main altar is made of carved wood covered with gold leaf.

Textiles of the Inca

The Incas were highly regarded for their textiles, which were influenced by the artistic works of the pre-Inca Chimú culture.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the importance of the Incan weaving tradition and its relation to earlier Chimú culture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Inca textiles were widely manufactured for practical use, trade, tax collection, and decorative fashion.

- Textiles were widely prized within the empire—in part because they were somewhat easily transported—and were widely manufactured for tax collection and trade purposes. Cloth and textiles were divided by class, with llama wool used in more common clothing and the finer cloths of alpaca or vicuña wool reserved for royal and religious use. Specific designs and ornaments marked a person’s status and nobility.

- The weaving tradition was very important to Incas in the creation of elaborate woven headdresses.

- Wealthy Inca men wore large gold and silver pendants hung on their chests, disks attached to their hair and shoes, and bands around their arms and wrists. Inca women adorned themselves with a metal fastening for their cloak called a tupu.

Key Terms

- cochineal: A vivid red dye made from the bodies of cochineal insects.

- tunic: A garment worn over the torso, with or without sleeves, and of various lengths reaching from the hips to the ankles.

- vicuña: A relative of the llama that lives in the high alpine areas of the Andes.

Background: Chimú Textiles

The Incas were highly regarded for their textiles, influenced by the artistic works of the pre-Inca Chimú culture. The Chimú, who arose about 900 CE, were conquered in a campaign led by the Inca ruler Tupac Inca Yupanqui around 1470 AD.

The Chimú embellished their fabrics with brocades, embroidery, fabric doubles, and painted fabrics. Textiles were sometimes adorned with feathers, gold, or silver plates. Colored dyes were created from plants containing tannin, mole, or walnut; these dyes also came from animals like the cochineal and minerals like clay, ferruginosa, and mordant aluminum. Garments were made of the wool of four animals: the guanaco, llama, alpaca, and vicuña. The people also used varieties of cotton that grew naturally in seven different colors. Clothing consisted of the Chimú loincloth, sleeveless shirts, small ponchos, and tunics.

Textiles in the Inca Empire

Textiles were widely prized within the Inca empire—in part because they were somewhat easily transported—and were widely manufactured for tax collection and trade purposes. Cloth and textiles were divided among the classes in the Inca empire. Awaska was used for common clothing and traditional household use and was usually made from llama wool. Qunpi, a finer cloth, was divided into two classes: it would either be made of alpaca wool and collected as tribute for use by royalty, or it would be woven from vicuña wool and used for royal and religious purposes. The finest textiles were reserved for the rulers as markers of their status. For example, Inca officials wore stylized tunics decorated with certain motifs, and soldiers of the Inca army had specific uniforms.

The Weaving Tradition

The weaving tradition was very important to Incas in the creation of beautiful and elaborate woven headdresses. Royalty was clearly distinguished through decorative dress. Inca emperors, for example, wore woven hats trimmed with gold and wool tassels or topped with plumes or showy feathers. Incas also created elaborate feather decorations for men, such as headbands made into crowns of feathers, collars, and chest coverings. Wealthy Inca men wore large gold and silver pendants hung on their chests, disks attached to their hair and shoes, and bands around their arms and wrists. Inca women adorned themselves with a metal fastening for their cloak called a tupu; the head of the tupu was decorated with paint or silver, gold, or copper bells.

Metalwork of the Inca

The Inca were well-known for their use of gold, silver, copper, bronze, and other metals for tools, weapons, and decorative ornaments.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the Incan use of copper, bronze, silver, gold, and other metals

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Drawing much of their metalworking style from Chimú art, the Incas used metals for utilitarian purposes as well as ornaments and decorations.

- Copper and bronze were used for basic farming tools or weapons, while gold and silver were reserved for ornaments and decorations in temples and palaces of Inca royalty.

- Gold was especially revered for its sun-like reflective quality; the Inca people’s reverence of gold has much to do with their worship of the sun and the sun god, Inti.

- Even though the Inca Empire contained many precious metals, the Incas did not value their metal as much as fine cloth.

Key Terms

- Chimú: A culture centered on Chimor, with the capital city of Chan Chan (in the Moche Valley of present-day Trujillo, Peru), which arose about 900 CE and was conquered by the Inca around 1470 CE.

- metallurgist: A person who works in metal.

- Inca: A member of the group of Quechuan peoples of highland Peru who established an empire from northern Ecuador to central Chile before the Spanish conquest.

Background

The Inca were well known for their use of gold, silver, copper, bronze, and other metals. Drawing much of their inspiration and style in metalworking from Chimú art, the Incas used metals for utilitarian purposes as well as ornaments and decorations. Although the Inca Empire contained a lot of precious metals, however, the Incas did not value their metal as much as fine cloth.

Many metalworkers were taken back to the capital city of Cusco after the fall of Chimú to continue their metalworking for the emperor because of their expertise. As part of a tax obligation to the commoners, mining was required in all the provinces, and copper, tin, gold, and silver were all obtained from mines or washed from the river gravels.

Tools and Weapons

Copper and bronze were used for basic farming tools or weapons, such as sharp sticks for digging, club-heads, knives with curved blades, axes, chisels, needles, and pins. The Incas had no iron or steel, so their armor and weaponry consisted of helmets, spears, and battle-axes made of copper, bronze, and wood. Metal tools and weapons were forged by Inca metallurgists and then spread throughout the empire.

Ornaments and Decorations in Metalwork

The Inca people’s reverence of gold, in particular, had much to do with their worship of the sun and the sun god Inti. Gold’s sun-like reflective quality made the precious metal even more highly regarded. Gold and silver were used for ornaments and decorations and reserved for the highest classes of Inca society, including priests, lords, and the Sapa Inca, or emperor. Gold and silver were common themes throughout the palaces of Inca emperors as well, and the temples of the Incas were strewn with sacred and highly precious metal objects. Thrones were ornately decorated with metals, and royalty dined on golden-plated dishes inlaid with decorative designs. Headdresses, crowns, ceremonial knives, cups, and ceremonial clothing were often inlaid with gold or silver.

The Spanish Conquest and Its Effects on Incan Art

After the fall of the Inca Empire, many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed or irrevocably changed by Spanish conquerors.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the effects of the Spanish Conquest on the art and culture of the Inca

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Following the Spanish Conquest, the Inca population suffered a dramatic and quick decline, largely due to illness and disease. Many of those remaining were enslaved.

- Many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed as cities and towns were pillaged, resulting in the loss of vast amounts of traditional artwork, craft, and architecture.

- The introduction of Christianity greatly impacted the art of the region, which began to reflect Christian themes alongside and in place of traditional Inca designs.

- Pizarro, the Spanish explorer and conquistador who was responsible for destroying much of the city of Cusco in 1535, built a new European- style city over pre-colonial foundations.The Spanish also brought with them new techniques such as oil painting on canvas, which fused with the artistic traditions of the region. This cultural melding could be seen in the works of the Cusco, Quito, and Chilote Schools.

Key Terms

- irrevocably: Beyond recall; in a manner precluding repeal.

Overview: The Spanish Conquest and the Fall of the Inca

The Spanish Conquest of the Inca Empire was catastrophic to the Inca people and culture. The Inca population suffered a dramatic and quick decline following contact with the Europeans. This decline was largely due to illness and disease such as smallpox, which is thought to have been introduced by colonists and conquistadors. It is estimated that parts of the empire, notably the Central Andes, suffered a population decline amounting to a staggering 93% of the pre-Columbian population by 1591.

As an effect of this conquest, many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed or irrevocably changed. In addition to disease and population decline, a large portion of the Inca population—including artisans and crafts people—was enslaved and forced to work in the gold and silver mines. Cities and towns were pillaged, along with a vast amount of traditional artwork, craft, and architecture, and new buildings and cities were built by the Spanish on top of Inca foundations.

The Role of Christianity

Beginning at the time of conquest, art of the central Andes region began to change as new techniques were introduced by the Spanish invaders, such as oil paintings on canvas. The spread of Christianity had a great influence on both the Inca people and their artwork as well. As Pizarro and the Spanish colonized the continent and brought it under their control, they forcefully converted many to Christianity, and it wasn’t long before the entire region was under Christian influence. As a result, early art from the colonial period began to show influences of both Christianity and Inca religious themes, and traditional Inca styles of artwork were adopted and altered by the Spanish to incorporate Christian themes.

Spanish Architecture

Pizarro, the Spanish explorer and conquistador who was responsible for destroying much of the city of Cusco in 1535, built a new European-style city over pre-colonial foundations. For instance, the Convent of Santo Domingo was built over the Coricancha (“Golden Temple” or “Temple of the Sun,” named for the gold plates covering its walls), which had been the most important sanctuary dedicated to the Inti (the Sun God) during the Inca Empire. The Convent was built in the Renaissance style and exceeds the height of many other buildings in the city.

The Convent and Church of la Mercad were similarly modeled on the Baroque Renaissance style, containing choir stalls, paintings, and wood carvings from the colonial era. The Cathedral of Santo Domingo was built on the foundations of the Inca Palace of Viracocha and presents late-Gothic, Baroque, and Plateresque interiors; it also has a strong example of colonial goldwork and wood carving. La Iglesia de la Compaña de Jesus was later constructed by the Jesuits over the foundations of the palace of the Inca ruler Huayna Capac, and is considered one of the best examples of the colonial baroque style in the Americas. Its façade is carved in stone, and its main altar is made of carved wood covered with gold leaf.

European Style Art

The majority of artistic efforts after the initial conquest were directed at evangelism; a number of schools of painting emerged that exemplify this. Indigenous artists were taught European techniques but retained styles that were representative of their local sensibilities. During the 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Baroque aesthetic was transplanted to central and South America and became especially influential, developing its own variations in different regions.

The Cusco School

The Cusco School was a Roman Catholic art movement that began in Cusco, Peru during the early colonial period. Initially developed by the Spanish to train local artists in the European tradition for the purpose of proselytizing, the style soon spread through Latin America to places as distant as the Andes, as well as to the places in present-day Bolivia and Ecuador. Cusco is considered to be the first location where the Spanish systematically taught European artistic techniques such as oil painting and perspective to Indigenous people in the Americas. Bishop Manuel de Lollinedo y Angulo, a collector of European art, was a major patron of the Cusco School and acted as a patron to such prominent artists as Basilio Santa Cruz Puma Callao, Antonio Sinchi Roca Inka, and Marcos Rivera. Cusco painting is characterized by exclusively religious subject matter; warped perspective; frequent use of the colors red, yellow, and earth tones; and an abundance of gold leaf. Artists often adapted the subject matter of paintings to include native flora and fauna. Most of the paintings were completed anonymously, a result of pre-Columbian traditions that viewed art as a communal undertaking.

The Quito School

The Quito School (Escuela Quitena) developed in the territory of the Royal Audience of Quito during the colonial period. The artistic production of this period was an important means of income for the area at the time. The Quito School was founded in 1552 by the Franciscan priest Jodoco Ricke, who transformed a seminary into an art school to train the first artists. The work of this period represents a long process of mixed-heritage blending of indigenous people and Europeans, both culturally and genetically.

Quito School artworks are known for their combination of European and Indigenous stylistic features, including Baroque, Flemish, Rococo, and Neoclassical elements. The technique of encarnado, or the simulation of the color of human flesh, was used on sculptures to make them appear more realistic. Another unique characteristic of the style was the application of aguada, or watercolor paint, on top of gold leaf or silver paint, giving it a unique metallic sheen. The racial blending of the time is reflected aesthetically in Quito School artworks in figures with mixed European and Indigenous traits, both in features and clothing. Artists included local plants and animals instead of traditional European foliage, and scenes were located in the Andean countryside and cities.

The Chilote School

The Chilote School of religious imagery is another artistic manifestation developed during the colonial period by Jesuit missionaries with the purpose of evangelizing. The works of this style or movement reflect the aesthetics of blending typical of other schools in the Americas from this era. Examples of this style include the combination of European, Latin American, and Indigenous features, as well as local flora, fauna, and landscape.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- plateresque. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/plateresque. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cusco. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cusco. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Inca Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cusco. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cusco. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kingdom of Cuzco. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Cuzco. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Prehistoric art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- antiquity. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/antiquity. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Machu Picchu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Machu_Picchu. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuscoinfobox. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuscoinfobox.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 450px-80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Machu_Picchu#/media/File:80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuzco1860. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuzco1860.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Aztec clothing. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_clothing. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Inca society. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_society. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Prehistoric art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chimu00fa culture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chim%C3%BA_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chimu00fa culture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chim%C3%BA_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- cochineal. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cochineal. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- tunic. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tunic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- vicuna. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/vicuna. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuscoinfobox. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuscoinfobox.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 450px-80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Machu_Picchu#/media/File:80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuzco1860. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuzco1860.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tupa-inca-tunic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tupa-inca-tunic.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Inca Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Inca society. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_society. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Inca society. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_society. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Inca. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Inca. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- metallurgist. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/metallurgist. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuscoinfobox. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuscoinfobox.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 450px-80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Machu_Picchu#/media/File:80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuzco1860. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuzco1860.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tupa-inca-tunic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tupa-inca-tunic.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Andean Bronze Age Bottle. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Andean_Bronze_Age_Bottle.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lombards Museum 198. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lombards_Museum_198.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Amerindian Civilizations: Civilizations in America: Pre-Columbian Era. Provided by: Saylor. Located at: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/HIST221-1.3.1-Amerindian-Civilizations-FINAL.pdf. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Inca Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inca_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_conquest_of_the_Inca_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Prehistoric art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- irrevocably. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/irrevocably. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spanish Art in the Americas. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: www.boundless.com/users/307859/textbooks/painting-1-8adf00aa-c11d-45a0-864a-1de2e11ad1f5/europe-and-america-in-the-1700s-and-early-1800s-11/spainish-art-111/spanish-art-in-the-americas-459-5782/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Architecture of the Inca. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: www.boundless.com/art-history/textbooks/boundless-art-history-textbook/the-americas-after-1300-ce-31/the-incas-193/architecture-of-the-inca-699-7703/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuscoinfobox. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuscoinfobox.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 450px-80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Machu_Picchu#/media/File:80_-_Machu_Picchu_-_Juin_2009_-_edit.2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuzco1860. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cuzco1860.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tupa-inca-tunic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tupa-inca-tunic.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Andean Bronze Age Bottle. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Andean_Bronze_Age_Bottle.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lombards Museum 198. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lombards_Museum_198.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- quenha-do-s-c3-a9culo-xvii.%402x.jpeg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: figures.boundless-cdn.com/16046/full/quenha-do-s-c3-a9culo-xvii.%402x.jpeg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The execution of Inca. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_execution_of_Inca.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- e-la-sangre-paso-encarnado.%402x.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cristo_de_la_Sangre_Paso_Encarnado.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright