18.7: The Aztecs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 264090

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Architecture of the Aztecs

Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital city from 1325–1521, is one of the most magnificent architectural accomplishments of the Aztec empire.

Learning Objectives

Describe the architecture of the Aztecs

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Founded in 1325, Tenochtitlan became the largest city in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica until it was captured by the Spanish in 1521.

- Built on a series of islets on the shores of Lake Texcoco, Tenochtitlan covered 3.1 to 5.2 square miles and was home to an estimated 212,500 people, which made it the 4th largest city in the world at the time.

- In the heart of the city were the massive Templo Mayor, a palace, two zoos, a botanical garden, a ceremonial center, and some 45 public buildings.

- When the Spanish conquered Tenochtitlan in 1521, Hernan Cortés ordered the destruction of the city and the rebuilding of the capital of New Spain atop its ruins. Today the ruins of Tenochtitlan are located in the central part of Mexico City.

Key Terms

- islet: A small island.

Aztec Architecture: An Overview

Aztec architecture refers to pre-Columbian architecture of the Aztec civilization, a civilization that dominated central Mexico in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. Their capital was Tenochtitlan on the shore of Lake Texcoco, the site of modern-day Mexico City. The architecture of the Aztecs was some of the finest in the world at the Aztecs’ height of power, and Tenochtitlan is perhaps the finest example of their advances.

History of Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan was the capital city of the expanding Aztec empire during the 15th century. Founded in 1325, it became the largest city in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica until it was captured by the Spanish in 1521. An ancient Aztec prophecy predicted that the wandering tribes would find the destined site for a great city. The Aztecs saw this vision on what was then a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco. Not to be deterred by the unfavorable terrain, they set about building their city, and a thriving culture soon developed. The small natural island was perpetually enlarged as Tenochtitlan grew to become the largest and most powerful city in Mesoamerica, with the Aztec civilization coming to dominate other tribes all around Mexico.

The power of Tenochtitlan was maintained by tributes paid by conquered lands and the capital grew in influence, size, and population. When Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519, he and his men were in awe at the sight of the splendid city. At this point it was the fourth largest city in the world—following Paris, Venice, and Constantinople—with an estimated population of 212,500 people (although some sources put the number as high as 350,000).

In 1521, the Spanish conquered Tenochtitlan, and Cortés directed the systematic destruction of the city and the rebuilding of the capital of New Spain atop its ruins. The resulting weight of the structures caused the ruins of Tenochtitlan to sink into the sediment of the lake. The location of the dismantled Temple Mayor was rediscovered only in the early 20th century.

The Architecture of the City

Tenochtitlan covered an estimated 3.1 to 5.2 square miles on the western side of the shallow Lake Texcoco. Built on a series of islets, the city plan was based on a symmetrical layout that was divided into four city sections, known as campans. Each campan was divided into 20 districts (calpullis), and each district was crossed by streets. The city was interlaced with canals used for transportation. At the heart of the city was the sacred precinct, home to about 45 public buildings, temples, and schools. Houses were made of wood and loam, and roofs were made of reed; pyramids, temples, and palaces were generally made of stone. The city center was also home to the ceremonial center, built inside of a 300-square meter walled square.

Surrounding the city and floating on the shallow flats of Lake Texcoco were enormous chinampas—long raised plant beds set upon the shallow lake bottom. Misnamed “floating gardens,” they were a very efficient agricultural system used to grow food for the city’s many residents. Two double aqueducts, each more than 2.5 miles long and made of terracotta, provided the city with fresh water for cleaning and washing.

Templo Mayor

Among the most famous of the buildings in the city center was the Templo Mayor, the twin pyramid dedicated to the Aztecs’ patron deities: Huitzilopochtli, god of war, and Tlaloc, god of rain and agriculture, each of which had a shrine at the top of the pyramid with separate staircases. The Great Temple measured approximately 328 ft by 262 ft at its base, dominating the Sacred Precinct. Construction of the first temple began sometime after 1325, and it was rebuilt six times. Mexican pyramids were typically expanded by building over prior ones, using the bulk of the former as a base for the latter, as later rulers sought to expand the temple to reflect the growing greatness of the city of Tenochtitlan.

The fourth temple was constructed between 1440 and 1481 during the reigns of Moctezuma I and Axayacatl. This stage is considered to have the richest of the architectural decorations, as well as sculptures. Its great platform was decorated with serpents and braziers, some of which are in the form of monkeys and some in the form of Tlaloc. At this time, the stairway to the shrine of Tlaloc was defined by a pair of undulating serpents, and in the middle of this shrine was a small altar defined by a pair of sculpted frogs. The circular monolith of Coyolxauhqui also dates from this time.

The seventh and last temple is what Hernán Cortés and his men saw when they arrived to Tenochtitlan in 1519. Very little of this layer remains because of the destruction the Spaniards wrought when they conquered the city: only a platform to the north and a section of paving in the courtyard on the south side can still be seen. The pyramid was composed of four sloped terraces with a passage between each level, topped by a great platform that measured approximately 262 by 328 feet. It had two stairways to access the two shrines on the top platform. The two temples were approximately 200 feet in height, and each had large braziers where the sacred fires continuously burned. The entrance of each temple had statues of robust and seated men, which supported the standard-bearers and banners of handmade bark paper. Each stairway was defined by balustrades flanking the stairs terminating in menacing serpent heads at the base; these stairways were used only by the priests and sacrificial victims. The entire building was originally covered with stucco and polychrome paint.

The deities were housed inside the temple, shielded from the outside by curtains. The idol of Huitzilopochtli was modeled from amaranth seeds held together with honey and human blood. Inside were bags containing jade, bones, and amulets to give life to the god. This figure was constructed annually, and it was richly dressed and fitted with a mask of gold for his festival held during the Aztec month of Panquetzaliztli. At the end of the festival, the image was broken apart and shared among the populace to be eaten.

The Palace of Moctezuma and Other Buildings

Other notable buildings in the city center included the temple of Quetzalcoatl; the tlachtli (ball game court) with the tzompantli or rack of skulls; the Sun Temple, which was dedicated to Tonatiuh; the Eagle’s House, which was associated with warriors and the ancient power of rulers; the platforms for the gladiatorial sacrifice; and some minor temples. Outside of the city center was the palace of Moctezuma with 100 rooms, each one with its own bath, which was used by the lords and ambassadors of allies and conquered people. The palace also had two houses or zoos, one for birds of prey and another for other birds, reptiles, and mammals. About 300 people were dedicated to the care of these animals. Also contained within the palace were a botanical garden and an aquarium, which had 10 ponds of salt water and 10 ponds of fresh water and contained both fish and aquatic birds.

Sculpture of the Aztecs

The Aztecs excelled in creating sculptures made of stone and other material, ranging from small works of art to monumental buildings.

Learning Objectives

Explain the symbolism of Aztec “skull art” and carved mirrors

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Aztec sculpture often represented gods and mythical creatures, and it was commonly expressed through ceramics, architecture, freestanding three-dimensional stone works, and relief work.

- The grand city of Tenochtitlan contained some of the finest examples of Aztec sculpture, from its temples and pyramids to its elaborate stone palaces.

- A great deal of Aztec sculpture incorporated the skull motif —what is today known in Mexico as “skull art.”

- Large carved obsidian mirrors were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from decorative to spiritual.The Aztec calendar stone is a large monolithic sculpture that was excavated in Mexico City in 1790 and is believed to have served multiple purposes.

Key Terms

- freestanding: Standing or set apart; not attached to anything.

- relief: A type of artwork in which shapes or figures protrude from a flat background.

- motif: A recurring or dominant element in a work of art.

- monolith: A large single block of stone, used in architecture and sculpture.

Overview: Aztec Sculpture

As with many Mesoamerican cultures, the Aztecs excelled in stone sculptures that ranged from small works of art to monumental buildings. Aztec sculpture often took the form of striking carvings of Aztec gods or mythical creatures, and it was expressed through ceramics, architecture, freestanding three-dimensional stone works, and relief work. The grand city of Tenochtitlan contained some of the finest examples of Aztec sculpture, from its temples and pyramids to its elaborate stone palaces.

Aztec Motifs

Skull Art

A great deal of Aztec sculpture incorporated the skull motif; today this is known in Mexico as “skull art.” In Aztec tradition, both death and life are worshiped together, and the skull—a symbol of death—was a promise of resurrection. The use of skulls and skeletons in Aztec art originated before the conquest, and the Aztecs often carved skulls into their stone sculptures, monoliths of lava, and masks of obsidian and jade.

Carved Mirrors

A unique and versatile form of sculpture was the carved mirror. Obsidian mirrors in pre-Columbian times were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from decorative to spiritual. During the late Post-classic period (c.1200–1521), these mirrors, symbolizing rulership and power, were used in rituals to spiritually access the Aztec underworld and communicate with the realm of the dead. Aztec mirrors were originally held in wooden frames and were decorated with perishable ornaments, such as feathers. During the Spanish conquest, Hernán Cortés was known to have sent obsidian mirrors back to the royal court in Spain, where they became widely collected among the European aristocracy.

Calendar Stone

One of the most well-known Aztec sculptures is the Calendar Stone. Also known as the Mexican Sun Stone, Stone of the Sun, or Stone of the Five Eras, it is a large monolithic sculpture that was excavated in the Zócalo, Mexico City’s main square, on December 17, 1790. The stone is 11.75 feet in diameter and 3.22 feet thick, and it weighs about 24 tons; on its surface are intricate carvings and sculpted motifs that refer to central components of the Mexica cosmogony. While the exact purpose of the stone is unclear, archaeologists and historians theorize that there could have been many functions to the stone, from spacial and time-related to political and spiritual.

Featherwork of the Aztecs

Featherwork, or the working of feathers into clothing and artifacts, was an especially elaborate practice among the Aztecs.

Learning Objectives

Identify the ways in which feathers were incorporated into Aztec artifacts

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Endowed with sacred meaning, feathers were associated with the Aztec patron deity Huitzilopochtli and the mythical god of featherworkers, Coyotlinahual.

- Feathers were incorporated into many aspects of life, including traditional clothing, armor for warfare, elaborate headdresses, and beautiful works of art.

- One of the most famous featherwork artifacts is the elaborate feather headdress thought to be worn by Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor at the time of the Spanish conquest.

- As Christianity spread through Mexico with the arrival of the Spanish, the use of feathers was adopted by Christians in the creation of religious objects.

Key Terms

- evangelization: The act of preaching the gospel or converting to Christianity.

- patron: An influential, wealthy person who supports an artist, craftsman, scholar, or aristocrat.

- quetzal: A strikingly colored bird with very long tail feathers, found in Guatemala and Costa Rica.

Aztec Featherwork

Featherwork is the working of feathers into a cultural artifact, which was an especially elaborate art form among the Aztecs. Endowed with sacred meaning, feathers were associated with the Aztec patron deity Huitzilopochtli and the mythical god of featherworkers, Coyotlinahual. Feathers were incorporated into many aspects of life, including traditional clothing, armor for warfare, elaborate headdresses, and beautiful works of art. Artisans specializing in featherwork often worked full-time to produce fine luxury goods for noble patrons during the height of the Aztec empire.

Symbol of Status

Perhaps the most well-known example of Aztec featherwork is the feather headdress, such as the one thought to be worn by Moctezuma II. As the Aztec emperor at the time of the Spanish conquest, his headdress was made of quetzal and other feathers and mounted in a base of gold and precious stone.

Aztec warriors, or cuāuhocēlōtl, were distinguished in bravery and skill by their helmets and uniforms. In particular, the Eagle Aztec warriors wore feathered helmets to mark their ability. Ornamental shields, or māhuizzoh chimalli, were often decorated with motifs made in featherwork.

Clothing

The huipil is the most common traditional garment worn today by indigenous women from central Mexico to Central America. It is the only garment in Mexico that uses the pre-Hispanic art of featherwork, and the most complicated designs are generally known only to a few older master weavers. Designs are embedded into the fabric of the huipil, along with decorative elements such as embroidery, ribbon, feathers, lace, wax, and even gold thread. After the Aztec Empire was invaded and conquered by the Spanish, the huipil evolved to incorporate elements from Europe and even Asia.

Effects of Evangelization

In the early years of evangelization, the Aztec’s use of feathers was adopted by Christians in the creation of religious objects, including feather paintings with Christian subjects. The sacredness of feathers, which for the Aztecs stemmed back long before the conquest, became associated with Christian forms of veneration. They were used to adorn triumphal arches, the bases of crosses, and the litters and canopies in which the host was carried during the Corpus Christi festival.

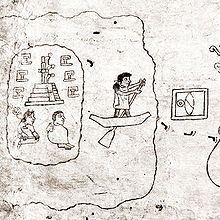

Codices of the Aztecs

Aztec codices, or pictorial manuscripts, are among the best primary sources of information on Aztec culture.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast pre-colonial and colonial Aztec codices

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Serving as calendars, ritual texts, almanacs, maps, and historical manuscripts of the Aztec people, codices spanned from before the Spanish conquest throughout the colonial era.

- Pre-colonial codices were largely pictorial in nature, while colonial codices contain Classical Nahuatl, Spanish, and even Latin.

- Few pre-colonial codices have survived, and codices created after the Spanish conquest were heavily influenced and even censored by the Spanish.

- The Florentine Codex, perhaps the most useful source of information on pre-colonial Aztec life, was created alongside a heavily censored version out of fear of Spanish authorities.

Key Terms

- codex: An early manuscript book bound in the modern manner, by joining pages, as opposed to a rolled scroll.

- pictorial: Described or otherwise represented by illustration rather than words.

Overview: Aztec Codices

The Aztec codices are manuscripts that were written and painted by tlacuilos (codex creators). One of the best primary sources of information on Aztec culture, they served as calendars, ritual texts, almanacs, maps, and historical manuscripts of the Aztec people, spanning from before the Spanish conquest through the colonial era. Pre-colonial codices differ from colonial codices in that they are largely pictorial and not meant to symbolize spoken or written narratives. The colonial-era codices not only contain Aztec pictograms, but also Classical Nahuatl (in the Latin alphabet), Spanish, and occasionally Latin.

Scholars now have access to a body of around 500 colonial-era codices, as well as a limited number of pre-colonial codices, though there are very few surviving codices from the pre-colonial era. While the tradition of codex-painting endured over the transition to colonial culture, codex production declined under the control of Spanish authorities, suggesting Spanish influence or even censorship in codex production.

Well-known Codices

Codex Borbonicus

The Codex Borbonicus is a codex written by Aztec priests around the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Like all pre-colonial codices, it was originally entirely pictorial in nature, although some Spanish descriptions were later added. It is a single 46.5-foot long sheet of paper made from amatl (fig bark); although there were originally 40 accordion-folded pages, the first two and the last two pages are missing.

Codex Borbonicus can be divided into three sections. The first section is one of the most intricate surviving divinatory calendars (or tonalamatl), and most of the page is taken up with a painting of the ruling deity or deities. With the symbols of the calendar, divided into 13-day periods, Aztec priests were able to create horoscopes and divine the future. The second section documents the Mesoamerican 52-year cycle, showing in order the dates of the first days of each of these 52 solar years. The third section is focused on rituals and ceremonies, particularly those that end the 52-year cycle, when the “new fire” must be lit.

The Boturini Codex

The Boturini Codex was painted by an unknown Aztec author some time between 1530 and 1541, roughly a decade after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. It tells the story of the legendary Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. Rather than employing separate pages, the author used one long, folded sheet of amatl.

The Florentine Codex

The Florentine Codex is perhaps the most useful source of information on Aztec life in the years before the Spanish conquest, even though the complete copy of the codex was not published until 1979. Prior to this, only a censored Spanish translation had been available. The codex is a set of 12 books created under the supervision of Bernardino de Sahagún between approximately 1540 and 1585. De Sahagún worked with the surviving Aztec wise men and taught tlacuilos to write the original Nahuatl accounts using the Latin alphabet. Because of fear of the Spanish authorities, he maintained the anonymity of his informants and wrote a heavily censored version in Spanish.

Codex Osuna

The Codex Osuna is a set of seven separate documents created in early 1565 to present evidence against the government of Viceroy Luis de Velasco during the 1563–66 inquiry by Jerónimo de Valderrama. In this codex, indigenous leaders claim non-payment for various goods and for various services performed by their people, including construction and domestic help.

The Aubin Codex

The Aubin Codex is a pictorial history of the Aztecs from their departure from Aztlán through the Spanish conquest to the early Spanish colonial period, ending in 1607. Consisting of 81 leaves, it was most likely started in 1576. It is also known as the “Manuscrito de 1576” (The Manuscript of 1576). Among other topics, the Aubin Codex has a native description of the massacre at the temple in Tenochtitlan in 1520.

Codex Magliabechiano

The Codex Magliabechiano, named after 17th century manuscript collector Antonio Magliabechi, was created during the mid-16th century. Primarily a religious document, it depicts the 20 day-names of the tonalpohualli, the 18 monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, and various deities, indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs.

Other Codices

- The Codex Mendoza was composed around 1541. It is divided into three sections: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquest, a list of the tribute paid by each tributary province, and a general description of daily Aztec life.

- The Codex Cozcatzin, dated 1572, lists historical and genealogical information focused on Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan. The final page consists of astronomical descriptions in Spanish.

- The Codex Ixtlilxochitl is an early 17th century codex fragment detailing, among other subjects, a calendar of the annual festivals and rituals celebrated by the Aztec teocalli during the Mexican year. Each of the 18 months is represented by a god or historical character.

- The Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis (“Little Book of the Medicinal Herbs of the Indians”) is an herbal manuscript describing the medicinal properties of various plants used by the Aztecs. The Libellus is also known as the Badianus Manuscript, the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, or the Codex Barberini.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History/Pre-Columbian. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/US_History/Pre-Columbian. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tenochtitlan | LACMA. Provided by: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Located at: www.lacma.org/tenochtitlan. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tenochtitlan. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tenochtitlan. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Jack Maxfield, America: A.D. 1401 to 1500. September 17, 2013. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/content/m17798/latest/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- The History of the Native Peoples of the Americas/Mesoamerican Cultures/Aztecs. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/The_History_of_the_Native_Peoples_of_the_Americas/Mesoamerican_Cultures/Aztecs. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- islet. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/islet. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Templo Mayor. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Templo_Mayor. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Templo_Mayor#/media/File:ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Templo Mayor 2007. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Templo_Mayor_2007.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mirrors in Mesoamerican culture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mirrors_in_Mesoamerican_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sculpture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sculpture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mexican art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Skull art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Skull_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec calendar stone. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_calendar_stone. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- relief. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/relief. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- freestanding. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/freestanding. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- motif. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/motif. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- monolith. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/monolith. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Templo_Mayor#/media/File:ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Templo Mayor 2007. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Templo_Mayor_2007.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec mirror, Museo de Amu00e9rica, Madrid. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_mirror,_Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica,_Madrid.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne%2C_sog._Aztekenkalender%2C_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_calendar_stone#/media/File:1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne,_sog._Aztekenkalender,_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Aztec statue of Coatlicue, the earth goddess. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_statue_of_Coatlicue,_the_earth_goddess.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Xiuhcoatl. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiuhcoatl. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//art-history/definition/evangelization. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancient Styles in the New Era | LACMA. Provided by: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Located at: www.lacma.org/ancient-styles. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Coyotlinahual. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Coyotlinahual. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Huipil. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Huipil. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Featherwork. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Featherwork. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Montezuma's headdress. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Montezuma's_headdress. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec warfare. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_warfare. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- patron. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/patron. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- quetzal. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/quetzal. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Templo_Mayor#/media/File:ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Templo Mayor 2007. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Templo_Mayor_2007.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec mirror, Museo de Amu00e9rica, Madrid. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_mirror,_Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica,_Madrid.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne%2C_sog._Aztekenkalender%2C_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_calendar_stone#/media/File:1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne,_sog._Aztekenkalender,_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Aztec statue of Coatlicue, the earth goddess. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_statue_of_Coatlicue,_the_earth_goddess.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Xiuhcoatl. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiuhcoatl. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Aztecheaddress. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztecheaddress.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Codex Feju00e9rvu00e1ry-Mayer. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Fej%C3%A9rv%C3%A1ry-Mayer. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The History of the Native Peoples of the Americas/Mesoamerican Cultures/Aztecs. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/The_History_of_the_Native_Peoples_of_the_Americas/Mesoamerican_Cultures/Aztecs. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Telleriano-Remensis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec codices. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_codices. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nahuatl/Pronunciation. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Nahuatl/Pronunciation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- pictorial. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pictorial. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- codex. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/codex. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Codex Corbonicus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Borbonicus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Templo_Mayor#/media/File:ScaleModelTemploMayor.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Templo Mayor 2007. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Templo_Mayor_2007.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aztec mirror, Museo de Amu00e9rica, Madrid. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_mirror,_Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica,_Madrid.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne%2C_sog._Aztekenkalender%2C_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_calendar_stone#/media/File:1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne,_sog._Aztekenkalender,_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Aztec statue of Coatlicue, the earth goddess. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_statue_of_Coatlicue,_the_earth_goddess.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Xiuhcoatl. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiuhcoatl. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Aztecheaddress. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aztecheaddress.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 614px-Codex_Borbonicus_(p._13) (1) 2.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Codex_Borbonicus_(p._13).jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Aztec codices. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_codices. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright