1.11: British Invasion

- Page ID

- 168912

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Rolling Stones

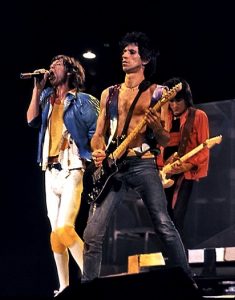

The Rolling Stones emerged at the same time as the Beatles, but epitomized the rebellious side of youth and were unconcerned with appealing to conventions. They played primarily rhythm and blues at the beginning of their career, but have since branched out. Still active today, they are one of the longest lived groups in popular music history.

Founded in 1962 by the original leader Brian Jones, the group took their name from the lyrics of Muddy Waters songs “Rollin’ Stone” and “Mannish Boy”. The members were Mick Jagger (Vocals, Harmonica), Keith Richard (Guitar), Brian Jones (Guitar), Bill Wyman (Bass), and Charlie Watts (Drums).

Most of their early hits were rock covers, including Chuck Berry’s “Come On”, the Beatles’ “I Wanna Be Your Man”, and Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away”. In addition to musical inspiration from American blues, the Stones covered soul and Motown songs, and Jagger’s dance moves were inspired by James Brown.

The Beatles came to America in 1964, and the Rolling Stones soon followed. They gained a reputation as bad boys, the opposite of the Beatles relatively safe image. The Stones’ manager, Andrew Oldham, was aware that groups able to write their own music tended to be more successful, and he encouraged them to write their own material. Jagger and Richards in particular became a strong songwriting team.

An early hit was “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction” (1965). Inspired by soul music, it was written by Jagger and Richards. Their original material indeed became more successful than their covers, and from this point on the Stones concentrated on writing. Listen below to ‘Satisfaction’ and in particular to the short guitar line that opens the song. This is an example of a Riff, a short, catchy musical item that is repeated throughout a song. Riffs have always been important in Rhythm and Blues, but British groups began to emphasize loud, distorted guitar riffs to help drive the music forward. In “Satisfaction”, Kieth Richards famously used a fuzz pedal to create a rich, lightly distorted tone to add a horn-like timbre to his guitar. Fuzz pedals were among the very first sound processing effects ever created for electric guitar, and are known for adding a “fuzzy” distorted tone very popular in rock and roll. Though the Stones were heavily indebted to blues, “Satisfaction” uses verse–chorus form. Examine the lyrics of the first few sections below and notice the refrain:

I can’t get me no satisfaction

And I try and I try and I try, t-t-t-t-try, try

I can’t get no

I can’t get me no

And a man comes on the radio

He’s tellin’ me more and more

About some useless information

Supposed to fire my imagination

I can’t get no

No, no, no

Hey, hey, hey

That’s what I say

I can’t get no satisfaction

I can’t get me no girly action

I can’t get no

I can’t get me no

And a man comes on to tell me

How white my shirts could be

But it can’t be a man ’cause he does not smoke

Same cigarettes as me

No, no, no

Hey, hey, hey

That’s what I say

Aftermath (1966) was their first album to feature all-original compositions. Also, the diverse musical talents of Brian Jones became evident. In addition to guitar, Jones contributed on instruments such as sitar, marimba, dulcimer, and many others. In 1967, they released Their Satanic Majesties Request which featured psychedelic artwork, exploratory experimental music, and drug influenced concepts. Seemingly at first an attempt to capitalize on the success of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, the album turned out to be much more experimental and strange than anything the Stones have done before or since. Many see the album as an interesting and unique point in the Stones’ career, but the band themselves don’t reflect as kindly on it. Around this time, the group was running into trouble with the law because of drug-related issues. In 1969, Brian Jones left the group and died in July of that year. He was replaced by guitarist Mick Taylor who stayed on until 1975.

In late 1969, the Stones decided to put on a free concert at Altamont speedway in California, modeled after Woodstock. The decision to use members of the Hell’s Angels (a biker gang…) as security instead of professionals turned the event into a disaster. Audience members were rowdy, with many under the influence of a variety of drugs; the ‘security’ themselves were drinking beer while working security. The audience members at the front were being pushed forward, many were beaten with pool cues, and one person was stabbed to death by the Hell’s Angels. Jagger attempted to control the audience, but the concert fell apart.

Their music began to branch further away from their rhythm and blues roots with the albums Let It Bleed (1969), Sticky Fingers (1971), and Exile on Main St. (1972). These albums are considered a classic period for the Stones as so many memorable songs came from them. This period saw the group incorporate country and folk influences, ballads, and a variety of instruments. “Wild Horses” from ), Sticky Fingers is one of the Stones most popular songs from this period (see Ch. 11 Listening Examples to listen)

By 1975, Mick Taylor left the group, partially out of frustration that the creative output of the group was so dominated by Jagger-Richards, and was replaced by Ron Wood who remains with the group today. The group continued to absorb outside influences, including disco with their 1978 album Some Girls. The band has continued to perform live and occasionally release albums, now into their 6th decade.

Listening Examples 11.1

The Rolling Stones:

- “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”

- “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” live

- “Sympathy for the Devil” live at the disastrous Altamont Festival

- “Wild Horses” is one of their most famous country-folk influenced ballads and comes from Sticky Fingers. The music opens with a rich texture featuring three different guitar parts before the drums, bass, and backing vocals join in at the B section (‘chorus’). The form follows an ABAB (verse-chorus) pattern with an instrumental middle C section featuring piano, no drums, and an understated electric guitar solo. This middle C guitar solo section returns immediately before the final B section.

- “Miss You” showcases the group incorporating elements of disco into their rhythm and blues. The disco influence lies mainly in the drums and bass, while the gritty blues sounds of the electric guitar and blues-style harmonica retain a strong link to their roots.

The British Invasion

In addition to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, there were many more bands that emerged from England to become popular abroad. Manchester, a neighboring city of Liverpool, was home to the groups the Hollies, named after Buddy Holly, and Herman’s Hermits, the most commercially successful Manchester group. The Hermits appealed to a younger audience than the Beatles with more of a pop music aesthetic. London group The Kinks also became popular with their hit “You Really Got Me” (1964). They experimented with new sounds such as “fuzz” tone by cutting their amplifier speakers.

Listening Examples 11.2

Herman’s Hermits: “I’m Into Something Good”

The Kinks: “You Really Got Me”

Finally, I demonstrate an approximation of the Kinks’ “Fuzztone” sound. I first play a chord with a completely clean guitar sound before kicking on the distorted sound and playing the riff to “You Really Got Me”. A more in-depth discussion of fuzz tone.

The Who

The Who formed in the early 1960’s, made up of Roger Daltrey (Vocals), Pete Townshend (Guitar), John Entwhistle (Bass), and Keith Moon (Drums).

The Who brought performance intensity to a new level, with Townshend strumming chords (sometimes using distortion or fuzz like many rock guitarists) with wild windmill arm movements, Daltrey swinging his microphone around, and Moon playing drums as violently as possible, while Entwhistle stood virtually motionless with a unique bass approach that was melodic, percussive, and and blindingly fast. They would often, in the early phase of their career, smash all their instruments as a climax to their performance.

In 1969, the “rock opera” Tommy was released as a double album. This expands the idea of the concept album to epic proportions, telling the story of a boy turned deaf, dumb and blind, but has a talent for playing pinball that “brings about a miraculous healing and return to the world of sight and sound.” Afterwards, they released other successful albums such as Who’s Next? (1971) and Who Are You? (1978) that incorporated many influences including classical minimalist music and synthesizers.

Drummer Keith Moon died in 1978, and John Entwhistle died in 2002, but the band continues to tour and record.

Listening Examples 11.3

The Who:

- “My Generation” live at Monterey Pop Festival (June 1967)

- An excerpt from a documentary that highlights The Who’s performance on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967 where The Who smashed their instruments and Keith Moon blew up his drum kit (literally).

- “Baba O’Reilly” (1971) from Who’s Next. The song incorporates fast polyrhythmic repeated figures in a synthesizer combined with The Who’s signature powerful riff-driven rock.

The British Blues Revival

The British Blues Revival of the 1960’s brought a number of talented musicians and bands into the spotlight. After Rock and Roll became popular in Britain and it began to be commercialized, some fans searched the roots of rock music and found the blues. Chris Barber was one of the early British musicians to form a band that incorporated blues into its music.

The blues covers played by British bands were not “cleaned up” the way they often were in America. Often, guitarists used bottleneck slides, string bending, and melodic phrasing similar to American blues performers. One feature that tends to distinguish British Blues vs Urban American blues is a heavier reliance on riffs, short, simple repeated ideas (a prime example is the riff from “Satisfaction” by The Rolling Stones, see Listening Examples 1.1) Another important leader in the revival was singer/harmonica player Cyril Davies whose band was a training ground for musicians such as Charlie Watts, Ginger Baker, Mick Jagger, and Jack Bruce.

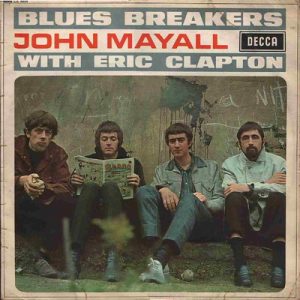

John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers

One of the most important blues revival groups was the one led by John Mayall (born 1933). This group served as another important jumping off point for many blues-rock musicians, one of the most notable being Eric Clapton. Mayall is often called the “Father of British Blues” because of his role in the British Blues Revival.

Mayall’s playing was true to blues tradition. Though many of the players who played in his band went on to have more commercial success, they were heavily influenced by their experience with Mayall. Some of the important musicians who played with the Blues Breakers include guitarists Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor, and Peter Green; bassists John McVie, and Jack Bruce; and drummers Aynsley Dunbar and Mick Fleetwood.

Perhaps the most famous album by John Mayall is Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton (1966, album cover above) which featured a young Eric Clapton providing groundbreaking electric guitar playing. Clapton’s style was heavily indebted to Urban Blues guitarists like B.B. King, but his sound was enhanced by a thick, throaty overdriven sound that proved influential on hard rock guitarists that followed, including Peter Green, Mick Taylor, Jimi Hendrix, and Jimmy Page. The opening song, “All Your Love” (Listening Examples 11.4), features a riff that drives much of the song. This is an example of the heavy use of guitar riffs in British Blues. Additionally, the song uses a traditional blues song form. Examine the lyrics below and see if you can tell what form it is.

All the loving is loving, all the kissin is kissing

All the loving is loving, all the kissin is kissing

Before I met you baby, never knew what I was missing

All your love, pretty baby, that I got in store for you

All your love, pretty baby, that I got in store for you

I love you pretty baby, well I say you love me too

All your loving, pretty baby, all your loving, pretty baby

All your loving, pretty baby, all your loving, pretty baby

Since I first met you baby, I never knew what I was missing

Hey, hey baby, hey, hey baby

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, baby, oh, oh, baby

Since I first met you baby, never knew what I was missing

The Yardbirds

The Yardbirds were an important group in the blues revival that achieved crossover success in the pop world. Formed in 1963, Eric Clapton replaced their original guitarist and the band was chosen by harpist Sonny Boy Williamson (No. 2) to be his backup band when he performed in England.

The Yardbirds covered many blues classics, but once the Beatles and others achieved pop success, the group decided to try the same. They scored a hit with “For Your Love” (1965), but Eric Clapton left the group, intent on playing the blues he loved. After Clapton left, rock guitar legends Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page filled the vacant lead guitar spot gaining their first widespread exposure. When Clapton left, he first joined the Blues Breakers, then left them to form his supergroup, Cream. Beck’s contributions to the group led to a more stylistically diverse approach, incorporating elements of psychedelic rock, Indian music, and jazz into the blues-based sound of the group. The song “Over Under Sideways Down” showcases an embellished lead guitar melody from Beck throughout.

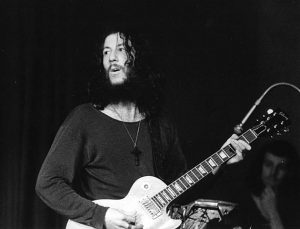

Cream

Cream was made up of Eric Clapton (Guitar, Vocals), Jack Bruce (Bass, Vocals), and Ginger Baker (Drums). Bruce and Clapton were alumni of John Mayall’s Blues Breakers. Clapton particularly liked their playing and put the band together himself, but Bruce and Baker had a previously volatile relationship and were reluctant to play together, though they eventually agreed. Their personal problems would eventually lead to a break only 2 years later.

Cream took the blues to a more intense volume, cranking the most powerful amplifiers to their limits, pointing the way towards harder rock styles. An example of Cream’s approach to the blues is evident in their version of Robert Johnson’s “Crossroad Blues” in which they take a traditional formal approach to the blues but stretch the piece out with improvisation for chorus after chorus. Their original songs showcase a number of influences and some reach far beyond their blues influence. Cream’s version of “Crossroads” also showcases the tendency for British Blues groups to use heavy, disorted riffs, as the song features a driving guitar riff right from the start. Notice the lyrical scheme of the first two sections below and compare to the Robert Johnson original:

Down to the crossroads, Fell down on my knees

Asked the Lord above for mercy, “Take me, if you please”

Down to the crossroads, Tried to flag a ride

Nobody seemed to know me, Everybody passed me by

Cream disbanded after little more than two years together, and Clapton went on to have a highly successful solo career.

Fleetwood Mac

Fleetwood Mac is known now primarily for the version that achieved commercial success in the 1970’s, but it in fact started out as a blues revival group led by guitarist/singer Peter Green.

Green got his start with the Blues Breakers, filling Clapton’s vacancy. There he met bassist Jon McVie and drummer Mick Fleetwood. Eventually, Green went out on his own with McVie and Fleetwood joining up. Joined by guitarist/singer Jeremy Spencer, and later guitarist/singer Danny Kirwan, the group played authentic blues classics and original compositions, some of which were in the blues tradition, and others that pointed in a new direction.

Fleetwood Mac had some successful hits, but Green was profoundly uncomfortable with fame and the amount of money they were making. In a fragile mental state made worse by excessive drug use, Green left the band. After a few years of shifting members, the group came back with a completely different sound and became hugely successful.

Listening Examples 11.4

John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers: “All Your Love”

The Yardbirds:“Louise” featuring Eric Clapton, “For Your Love” Live featuring Jeff Beck

Cream: Listen to the live recording of “Crossroads” , and compare it to the original Robert Johnson recording from the week 1 lecture. Notice how extensive improvisation for chorus after chorus takes an important role. Cream’s interpretation of the song has much in common with the urban blues of performers such as BB King, albeit with more intense volume and harder hitting drums. Now listen as I play through an entire section of “Crossroads” in the style of Cream. Try and follow/count the section in this new, distorted and rock-oriented style.

Fleetwood Mac:“The World Keeps Turning” is a blues original by Peter Green that evokes the early blues of Robert Johnson, featuring uneven bar and phrase lengths.