1.12: American Folk Music

- Page ID

- 168914

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)1960s and American Folk Music

The 1960’s were a time of turmoil in the U.S, and folk music served as an important voice against racism, the Vietnam War, and spread through many college campuses. Lyrics became the most important element of the art form, with many folk singers of the 1960s singing out against the Vietnam War, segregation, and other political/social issues. American folk music wasn’t notated; rather, it was passed down through an oral tradition until audio recording began. Each song would differ depending on the performer. It came from a variety of old world sources depending on where in Europe settlers of a given region had come from.

Musicologists Charles Seeger, John Lomax, and Alan Lomax were responsible for researching, analyzing, notating, and recording a large amount of American folk music. This preserved many folk songs that could have been lost otherwise, and the music was collected for the Library of Congress.

American folk is primarily vocal music and the instruments are usually used to accompany the vocals, though instruments like fiddle and recorder supplied melody. Folk musicians tended to avoid using electric instruments for the most part even after they became standard in popular music. Acoustic instruments are very important to the rural tradition of folk music.

Pete Seeger

Pete Seeger – (1919 – 2014) Pioneering American folk singer and the son of Charles Seeger, American composer and musicologist. He played guitar and banjo, and, incorporating his father’s scholarly work, began playing American folk music, bringing it to the attention of many in the 1940’s. He remained a vital and active performer into his early 90’s.

He began performing many of the songs his father documented as well as writing his own songs. Seeger formed the Almanac Singers in 1941. This group, which included Woody Guthrie, took traditional folk music and incorporated texts that spoke of the social and political concerns of the time, such as civil rights, labor unions, and the need to end war.

He formed the Weavers in 1948, whose harmonized vocals and energetic performance style became popular with Americans. They continued incorporating lyrics of social concerns, and their left wing tendencies in songs such as “I Don’t Want Your Millions Mister” (found in Ch. 12 Listening Examples) caused them to lose some of their audience in the early 1950’s when they were investigated by the House of Un-American Activities committee. While the songs were lyrically controversial, formally they were traditional and conservative “I Don’t Want Your Millions Mister” features two A sections repeated throughout the entire song. It alternates a chorus/refrain ‘A’ with the whole group harmonizing and singing the same lyrics in each iteration, and a verse ‘A’ with Pete Seeger singing solo, with different lyrics each iteration. The reason I call both sections ‘A’ is because the music itself (chords and vocal melodies) are virtually identical between the sections.

After the Weavers disbanded, Seeger continued with a solo career until his death in 2014, all the while supporting various social causes.

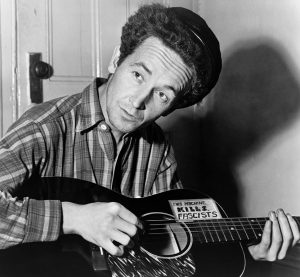

Woody Guthrie

Woody Guthrie – (1912–1967) Had spent many years traveling and performing before joining the Almanacs with Pete Seeger. Inspired by American folk and blues singers such as Leadbelly, he sang of modern concerns by putting new text to traditional melodies as well as composing his own folk-styled compositions.

Alan Lomax saw Guthrie as an important folk artist and recorded a collection of his songs for the Library of Congress. He was a folk singer for modern times; Guthrie sang war songs in support of WWII, painting “This machine kills fascists” on his guitar. Some of his original songs have become classics, including “This Land Is Your Land” and “So Long, it’s Been Good to Know You”.

Below are lyrics from the first three sections of “This Land is Your Land”. Notice the arrangement of the lyrics; each section ends with the same line, “This land was made for you and me.” The form is a common one in folk and can be described as repeated A sections with a refrain at the end of each section.

From the California, to the New York Island

From the Redwood Forest, to the Gulf stream waters

This land was made for you and me

I saw above me that endless skyway

Saw below me the golden valley

This land was made for you and me

To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts

All around me a voice was sounding

This land was made for you and me

Guthrie was diagnosed with a degenerative disease of the nervous system, and was unable to perform from the mid 1950’s, but his influence on American folk music (Bob Dylan was a Guthrie devotee) was profound.

Listening Examples 12.1

Pete Seeger and the Almanac Singers: Pay attention to the lyrics in “I Don’t Want Your Millions Mister”, which take a left-leaning, somewhat anti-capitalist view point. Songs such as this did not help their popularity in the climate of 1950s United States, but they did appeal to a growing segment of the country’s youth who would have a greater role into the 1960s.

Woody Guthrie: Guthrie wrote “This Land in Your Land” (1940) as an honest and inclusive patriotic song and was supposedly written as a reaction upon hearing a recording of “God Bless America”. Notice how the song uses the same section of music repeatedly. This includes the same melody and accompaniment, but the lyrics change with each section. Another example of his work is “Greenback Dollar”. Finally listen as he sings “Tear the Fascist Down”. Lyrically, the song is actually pro-war (unusual in folk music!) protesting American non-involvement at a time in World War II when Germany appeared to be taking control of the entire European continent.

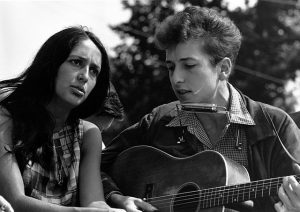

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (Born Robert Zimmerman in 1941) Was a follower of Woody Guthrie and went on to become a leading figure for the youth culture of the 1960’s. Dylan’s impact was enormous and changed the course of popular music around the world. As a young man he visited Guthrie in the hospital, learning from him and playing music in coffee houses in New York. Here he attracted a following and was noticed by Columbia Records where he was given a contract. His first album, Bob Dylan, was released in March 1962 and consisted mainly of traditional folk songs, arrangements by Dylan, and only two original compositions.

With his 2nd album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) he used primarily original material including traditional folk melodies with new text added. In these songs Dylan sang of relevant issues affecting the people of the time of which there were many; the Cold War and all the paranoia associated with it, segregation and other racial inequalities, gender inequality, the emerging Vietnam war, and the emerging cultural revolution in the United States. These topics are sometimes discussed outright in the lyrics, other times they are presented in a poetic fashion with metaphor and surreal imagery. This level of lyrical depth had rarely been seen in popular music, the precedents being singers like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

The opening track on the album, “Blowin’ in the Wind”, became a popular anti-war statement of peace and equality, especially after it was recorded by Peter, Paul, and Mary, another popular folk group. Lyrically, the song uses creative imagery in the form of questions to evoke it’s statement. The questions form the verse (A) and are different each iteration. The refrain shows up the same each time as the ambiguous “answer”. The form features multiple verses with these short refrains at the end each time. As with any interpretation of lyrics/poetry, it is always good to remind the readers that an analysis is subjective. Below are the complete lyrics including verses and refrains of “Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan. (Music can be found in Ch. 12 Listening Examples)

Before you call him a man?

How many seas must a white dove sail

Before she sleeps in the sand?

Yes, and how many times must the cannonballs fly

Before they’re forever banned?

The answer is blowin’ in the wind

Before it is washed to the sea?

And how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

The answer is blowin’ in the wind

Before he can see the sky?

And how many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry?

Yes, and how many deaths will it take ’til he knows

That too many people have died?

The answer is blowin’ in the wind

.

The first question seems to deal with maturity, growth, age, perhaps the reluctance of the older generations and those in power at the time to take the contrasting (and sometimes radical) views of the younger generations of the 1960s seriously. It could also be interpreted as a question on civil rights, in other words how long will it take for people to treat each other as equals, regardless of their race, nationality, etc. The second question contains the image of the white dove, traditionally associated with peace. This question could be asking how long can the idea of peace exist in the hearts and minds across the oceans of world before it finally becomes accepted and practiced by all. The third question makes it obvious that Dylan is questioning human nature, and asking how long will it take until humanity can grow beyond violence, greed, and perpetual conflict. The ambiguity of the refrain that “The answer is blowin’ in the wind” is an honest answer from Dylan. He admits he doesn’t know the answers to the questions, but realizes the importance of posing the questions in the first place to get people thinking about the answer.

Dylan released The Times They Are A-Changin’ in 1964 which contained more songs of a socially conscious nature. The title track (music can be found in Ch. 12 Listening Examples) captures the mood of the times, one of changing social attitudes and frustration at the inequities in American society. In the song Dylan sings of this change in mood, urging people to evolve and grow. Each of the five verses end with the same short refrain “For the times they are a-changin’. The first two verses are as follows:

Come gather ’round people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You’ll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin’

And you better start swimmin’

Or you’ll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin’

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won’t come again

And don’t speak too soon

For the wheel’s still in spin

And there’s no tellin’ who

That it’s namin’

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin’

Also in 1964, Dylan released the album Another Side of Bob Dylan. As the title suggests, the album marks a shift from the protest songs of his previous work to a more personal realm in which poetics, metaphor, and surreal imagery begin to play a bigger role. The music reflects some of the personal shifts in Dylan’s life including his first use of psychedelic drugs and his growing knowledge and appreciation for poetry, literature, and music outside of the folk genre including the Beatles. The song “It Ain’t Me Babe” is an example of Dylan’s shift to personal topics. In the song he sings to a woman explaining he is not nor can he ever be the type of man she’s looking for. The lyrics are alternately cold and compassionate; Dylan is apologetic but he’s not trying to pretend to be a better person than he really is. Again, the music features multiple verses with a refrain at the end. (see Ch. 12 Listening Examples)

The first verse:

Go ‘way from my window

Leave at your own chosen speed

I’m not the one you want, babe

I’m not the one you need

You say you’re lookin’ for someone

Who’s never weak but always strong

To protect you an’ defend you

Whether you are right or wrong

Someone to open each and every door

But it ain’t me, babe

No, no, no, it ain’t me, babe

It ain’t me you’re lookin’ for, babe

In 1965 he shocked and angered his folk base by turning to more rock oriented sounds on his live appearances and albums. The album Bringing It All Back Home (1965) showcased this new sound. This move helped create a new genre called “Folk Rock”. The first side of the album featured an electric band backing Dylan while the second side featured his normal acoustic sound. Lyrically, the music continues in the direction of personal and abstract poetics. The opening track “Subteranean Homesick Blues” features an electric band, strange and and abstract lyrics, and a vague reference to the blues in the chords of the song. The lyrics are abstract, but there are references to relevant contemporary subject matter such as recreational drugs as well as the emergence of the emerging counter culture in America and it’s clash with mainstream society.

The first verse:

Johnny’s in the basement

Mixing up the medicine

I’m on the pavement

Thinking about the government

The man in the trench coat

Badge out, laid off

Says he’s got a bad cough

Wants to get it paid off

Look out kid

It’s somethin’ you did

God knows when

But you’re doin’ it again

You better duck down the alley way

Lookin’ for a new friend

The man in the coon-skin cap

By the big pen

Wants eleven dollar bills

You only got ten

(see Ch. 12 Listening Examples)

Also in 1965 Dylan released Highway 61 Revisited, one of his most highly regarded albums. Throughout, Dylan’s lyrics continue the personal and abstract poetic tone from previous albums, but also begin to take on a more cynical and angry tone. This likely has to do with some of the criticisms thrown at him from the press and critics as well as “fans” who were angered by Dylan’s move to electric music. The first song off the album is one of Dylan’s most well known and influential, called “Like a Rolling Stone”. The song actually proved to be a hit single for Dylan, proving he was still popular and respected even though he was being criticized by a small but vocal minority. “Like a Rolling Stone” features an angry lyric about a woman who was at one time a person of means and money, and looked down upon the poor and non-conformists, and is then thrust into the very life she looked down on, confronted with the realities and difficulties faced by those she didn’t understand before. The song is in Verse-Chorus form and the lyrics of the first verse and chorus are as follows:

Verse 1:

Once upon a time you dressed so fine

You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you?

People’d call, say, “Beware doll, you’re bound to fall.” You thought they were all kiddin’ you

You used to laugh about Everybody that was hangin’ out Now you don’t talk so loud Now you don’t seem so proud About having to be scrounging for your next meal

Chorus/Refrain: How does it feel? How does it feel? To be without a home Like a complete unknown Like a rolling stone?

Verse 2: Ahh you’ve gone to the finest schools, alright Miss Lonely

But you know you only used to get juiced in it. Nobody’s ever taught you how to live out on the street, And now you’re gonna have to get used to it. You say you never compromise, With the mystery tramp, but now you realize

He’s not selling any alibis, As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes, And say do you want to make a deal?

Chorus/Refrain: How does it feel? How does it feel? To be without a home Like a complete unknown Like a rolling stone?

(see Ch. 12 Listening Examples)

Notice how in songs such as “Blowin in the Wind” and “The Times They are A-Changin” the refrain is a short, single line that is musically “attached” to the main A section (verse). The difference in “Like a Rolling Stone” is that the chorus/refrain is longer and musically distinct from the verse. It feels like a new, independent section of music. This is why we call it verse-chorus form in this case.

In 1965, Dylan went on tour with a band performing music in the electric format. Throughout the tour, Dylan and co. encountered hostile audiences who for some reason felt that Dylan was insulting them by presenting the electric sound. This was a particular problem on the tour of England where some bootleg recordings showcase an audible conflict between Dylan and audience members.

In 1966, Dylan released Blonde on Blonde, a double album (2 records) frequently lauded as one of the best albums in popular music history. The album continues the inclusion of rock-oriented sounds via an electric backing band as well as Dylan’s continued lyrical growth. The album was recorded in both New York City and Nashville, and the Nashville sessions featured expert studio musicians normally associated with country music, adding a sense of authentic Americana to the album. One of the most well known and critically acclaimed songs from the album is “Just Like a Woman”. Though accused of misogyny at times, the song is part of Dylan’s growing cynicism and distance from people in general. The song features Verse-Chorus form, and also features a bridge (a third, contrasting section of music).

In 1967, Dylan took an extended break from touring, retreating to Woodstock New York to relax and write new material. During this time he was involved in a motorcycle accident which contributed to the extended nature of the break, though some believe the stress of fame and the rigors of his 1965-66 tours pushed him away from the spotlight. While recovering from a motorcycle accident, Dylan’s backup band decided to try touring on their own, calling themselves The Band and became an creative and influential group on their own. When he returned to the studio Dylan began to return to his acoustic folk roots and also began working in a country music style, releasing the albums John Wesley Harding (1967) and Nashville Skyline (1969) the latter which featured a new sound; a change in his vocal tone, dispensing with the gritty speech-singing style for a more pure, country-based sound. Lyrically, the songs on Nashville Skyline offer a more simple, approachable lyric style than some of his previous work.

Throughout the 1970s Dylan resumed touring, including appearances with Joan Baez, The Band, and George Harrison. He continued producing work in folk and country genres, having a hit in 1973 with “Knocking on Heaven’s Door”. In the late 1970’s Dylan became a born-again Christian, and his music began reflecting that. Lyrically, one can find frequent biblical references among his poetic tendencies. The song “Every Grain of Sand” (see Ch. 12 Listening Examples) from Shot of Love (1981) is one of his most beautiful songs, musically and poetically. While certainly related to his particular conversion to Christianity, the lyrics can be interpreted universally.

In the 1980s, Dylan joined The Traveling Wilburys along with George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty. Also around this time, he began a heavy touring schedule that has continued uninterrupted to this day. Dylan continues to release a steady stream of albums of high quality, though always unpredictable. He released the highly acclaimed album Tempest in 2012, consisting almost entirely of original songs, while his latest releases Shadows in the Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016) and Triplicate (2017) consist of cover versions of traditional pop songs.

Listening Examples 12.2

- “Blowin’ in the Wind”, “Blowin’ in the Wind” live, lyrics

- “The Times They Are A-Changin”, “The Times They Are A-Changin” live, lyrics

- “Like a Rollin’ Stone”, “Like a Rollin’ Stone” live in England 1966

- “I Shall Be Released’ w/ The Band, “I Shall be Released” live from The Last Waltz, lyrics

- “Every Grain of Sand”, Lyrics to “Every Grain of Sand

Folk Rock

The Byrds

The Byrds were a rock group that formed in 1964 and adopted a folk repertoire. The combination of rock instruments and folk songs helped start the genre known as “folk-rock”. They created a highly distinctive sound with their complex, closely harmonized vocals and singer-guitarist Roger McGuinn’s use of the 12-string electric guitar. The group was heavily indebted to folk artists like Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger; 1/4 of the 12 songs on their debut were written by Bob Dylan and the album title was Mr. Tambourine Man, after the Bob Dylan song. The Byrds’ cover version of the song “Mr. Tambourine Man” was a hit for the group and featured some changes to the original version (see Ch. 12.3 Listening Examples). The song was expedited: the Dylan version was 5-6 minutes long, while the Byrds’ version was a radio-friendly 2:29, leaving out much of the lyrical content of the original. It was also a slower tempo and made use of the Rickenbacker 12-string electric guitar mentioned earlier, an instrument George Harrison of the Beatles had helped to popularize. The acoustic 12-string guitar was a popular folk instrument, and the electric 12-string was a way to retain a thoroughly “Folk” sound in electric music.

“Turn Turn Turn!” from their second album of the same name became one of the Byrds’ most well known recordings (see Ch. 12.3 Listening Examples). The song was written by Pete Seeger originally and feature words from the Bible (Ecclesiastes). Seeger used the biblical words to relate to the modern world as a plea for peace. The Byrds transformed the song from an acoustic folk song into a twangy anthem of beautifully harmonized group vocals and chimey electric 12 string guitars. The song uses mixed meter, where multiple bar lengths are used. Most of the song uses 4 beat bars (as in 12- bar blues for example), but a 6 beat bar is used as well. Try counting the beats for the first vocal section: “To everything turn, turn, turn” should come out to 10 beats (one 4-beat bar and one 6-beat bar). This seems complex, but it fits the phrase of the vocal melody perfectly and in fact a mix of 4 and 6 beat bars was used by the Carter Family in the song “You Are My Flower” from 1927, so it is actually a relatively common feature in folk music.

The group later experimented with innovative psychedelic rock on songs such as “8 Miles High” from their third album 5th Dimension (1966) (see Ch. 12.3 Listening Examples). This song is often mentioned as being one of the earliest examples of psychedelic rock. The music is influenced by the drones and melodic tendencies of classical Indian music by artists such as Ravi Shankar and experimental jazz artists like American saxophonist John Coltrane. In 1968 the group began experimenting with country music. (see ch. 14)

Other Developments in Folk

Some folk musicians such as Tom Paxton, Barry McGuire, and Phil Ochs continued developing socially conscious lyrics in the Woody Guthrie tradition. They sang in protest of war and the glorification that society put on it, and of a need for peace and unification.

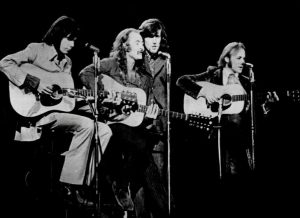

The supergroup Crosby, Stills and Nash became popular with many hit songs and an utterly unique vocal harmony style. The group was formed by David Crosby (of The Byrds) Steven Stills (of Buffalo Springfield) and Graham Nash (of The Hollies). Their style can be described as folk-rock in that they would mix purely acoustic sounds with full band electric ensembles. They were occasionally joined by Neil Young at which times they would be known as Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young.

CSNY sang a mixture of protest songs and personal songs. Each member brought a unique songwriting style and vocal style to their sound. One of their best known songs, “Ohio” (1970) was written by Neil Young and is a powerful commentary on the killing of four students by national guardsmen during a protest on an Ohio college campus. “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes”, written by Steven Stills, is a song that displays the groups signature vocal harmonies (see Ch. 12 Listening Examples). The song defies our standard pop song forms by going through a number of different, contrasting sections, culminating in the upbeat and very catchy final section. “Guinnevere”, written by David Crosby, is a hauntingly beautiful love song that is remarkably progressive in its use of alternate guitar tunings and chords, as well as the complex mixtures of rhythms and melodic patterns. The opening guitar pattern features a rhythmic pattern of 3+3+2 or 1-2-3 1-2-3 1-2. “Teach Your Children”, written by Graham Nash, is one of the group’s most enduring compositions. Featuring the groups classic vocal harmonies, a wonderful melody that is simple and memorable, and pedal steel lines by none other than Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead (see Ch. 13), the song is best known for it’s universal message to “Teach your children well”.

Singer/Songwriter James Taylor sings of personal struggles, relationships, and other topics of personal nature (which was to become more common after the 1960’s), and has a characteristically gentle singing style and intricate guitar style. In 1970 he had a hit with the song “Fire and Rain” (Ch. 12 Listening Examples).

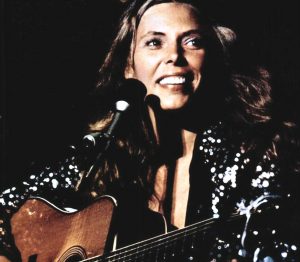

Joni Mitchell

Singer/Songwriter Joni Mitchell has had one of the most creative and diverse careers in American folk music. She sings with a very unique voice that changes timbre in different registers, and incorporates pop, jazz, and other influences into the folk style. Her band members change from time to time, and can be comprised of folk musicians, rock musicians, jazz musicians, or just Mitchell herself on guitar or piano. Mitchell also experiments with new tunings on her guitar, creating brand new sonorities to accompany her voice. Lyrically, Mitchell’s songs generally feature a highly personal perspective.

Mitchell was born in Canada but moved to the United States to pursue a career in music. Her unique voice and prolific, innovative songwriting helped her release a steady stream of albums. Ladies of the Canyon (1970) featured one of Mitchell’s most enduring songs, “Big Yellow Taxi” which featured socially conscious lyrics (somewhat uncommon for Mitchell) on the topic of the environment. Blue (released in 1971) is one of her best loved albums, exploring themes on the complexities and difficulties of love. Mitchell’s lyrics are painfully personal, giving the listener a sense of reading a diary meant for the writer’s eyes/ears only. The song “Little Green” is a song about a child given up for adoption; Mitchell is writing from personal experience as she gave up her daughter many years before (they would later reconnect). Without a band or electric instruments, these emotions are laid naked in the raw context of such spare instrumentation. Conversely, at certain times Mitchell creates beautifully lush and dense textures on piano and guitar to accompany her voice, such as the piano playing on the song “Blue”.

On the album Court and Spark (1974) Mitchell began an association with jazz that endured through the rest of the 1970s, blossoming an experimental style in which the guitar was tuned in brand new ways, new chords were used, and unusual or abstract lyrics were employed. On the song “Don’t Interupt the Sorrow” from The Hissing of Summer Lawns (1975) utilizes these unusual characteristics: Abstract lyrics, open tuned guitar, and unusual chords. The song also showcases an expanded instrumentation featuring a plethora of percussion instruments and electric rock instruments.

Listening Examples 12.3

The Byrds:

- “Turn Turn Turn”

- “Mr. Tambourine Man” Now, listen to Bob Dylan’s version in contrast to the Byrd’s.

- “Eight Miles high”

Crosby Stills and Nash:

- “Ohio”

- “Judy Blue Eyes” – Notice the dense and complex vocal harmonies

- “Guinnevere” – Unconventional chords and a 3+3+2 rhythmic scheme

- “Teach Your Children”

James Taylor: “Fire and Rain”

Joni Mitchell:

I compare standard guitar tuning vs. a tuning used by Joni Mitchell on the song “Coyote” (from Hejira, released 1976) followed by the opening chords from “Coyote”. Standard guitar tuning is structured in a way that many chords in many keys can be played relatively easily. The tuning used by Mitchell (which I’m calling an “open C” tuning) is tuned to a particular chord, and even though it is not as versatile as standard tuning, it opens up possibilities for new chords that are impossible to play in standard tuning. It is a similar tuning as that used on “Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow”, different by a couple of notes.