1.1: Defining Popular Music and Stephen Foster

- Page ID

- 168896

“Popular Music” can be defined as music that has a broad appeal to popular tastes; in other words a large portion of the population appreciate and enjoy it.

Popular Music encompasses an incredibly wide range of styles, some of which are seemingly unrelated. For example, Punk, Country, and Disco all fall under this umbrella term for their wide appeal. These styles can be traced back to earlier styles.

Certain musical characteristics are often times identifiable in the many styles of popular music.

- Vocals are often present and at the forefront of the musical texture.

- Along with vocals, lyrics (the words set to the music), are also at the forefront of the musical texture.

- Usually, each individual song is relatively brief.

- Many popular songs follow certain formal characteristics.

- The music is very often structured in 4-beat patterns.

Origins of Music

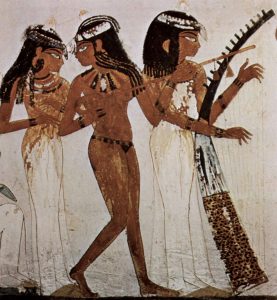

Humans have been making music for thousands of years as evidenced by the Divje Babe flute pictured here and the above painting of three musicians from the Tomb of Nakht, Thebes ca. 1422-1411 BCE. Of course, this is long before audio recording and musical notation were available. The earliest music notation was first developed around 2000 BC, but didn’t start approaching it’s modern form until the middle ages in Europe.

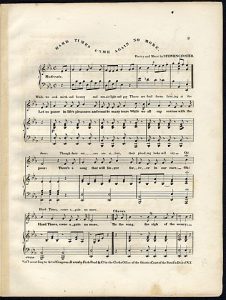

Once music was able to be notated and mass produced, popular music began to develop on the scale we know it today. With more families buying pianos, there was higher demand for sheet music of popular songs. Still, most popular songs were passed down from person to person rather than documented in notation. Once audio recording technology was developed in the 19th century, a wide variety of popular music became easily available.

To the right is an image of the Divje Babe flute, discovered in Slovenia in 1995 and it represents how deeply music falls into the timeline of human history. The flute is carved from a cave bear femur and at approximately 43,000 years old represents an example of a relatively sophisticated musical instrument. Such instruments were most certainly predated by percussion and especially by the human voice, both of which, as musical instruments, undoubtedly go back even further into human history.

Quick Music Fundamentals Terms List

Melody: A series of pitches that unfold over a period of time. A melody is like a sentence with a beginning, middle, end, high point, low point, contour, and structure. Often, these elements are linked in some way to the words Think of a song everyone knows, like “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star”. Sing it to yourself and notice the form of the melody. First we sing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, How I Wonder What You Are” then we sing “Up Above the World So High, Like a Diamond in the Sky” and then finally “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, How I Wonder What You Are”. Notice the first and third sentences are not only the same words, but the same melody. The second line is contrasting not only in the words but in the melody.

Rhythm: Divisions of music into patterns over time. Rhythm is what gives music it’s dance-ability. Rhythm is made up of a series of accents or pulses called beats. Think of a clock for example; it beats 60 times per minute (each second is a beat in this case), and each beat is even. This is an example of tempo, also known as the speed of the music. Meter is the term for how many pulses or beats make up a phrase of the music. For example, the majority of popular music uses a meter with 4-beat patterns. Other patterns such as 3-beat patterns are often used as well.

Chords: A series of pitches sounding at the same time, most often used to accompany melodies. Can be played with different rhythmic patterns. A chord is simply a way of arranging a series of pitches to provide a background over which a melody can have context. Most often, the chords themselves will contain notes from the melody.

Listening Examples 1.1

A brief demonstration of the concepts of melody, chords, and rhythm demonstrated using “Twinkle Twinkle”. Seemingly childish, but it’s a tune most of us know by heart! I first play the melody alone to give you a sense of the contour/structure, then I apply the chord changes to accompany the melody which gives it a sense of completeness. All the while, the entire tune uses a 4-beat pattern. Try counting 1-2-3-4 on each melody note to get a sense of the 4-beat pattern.

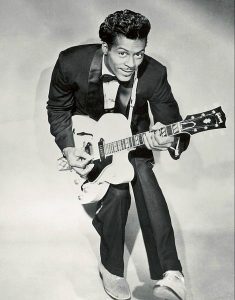

Early American Popular Music: Stephen Foster

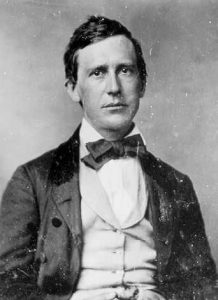

Stephen Foster is often called the “Father of American Music”. Widely considered the first great American songwriter, Foster’s music became well-known and loved by the American public in his brief lifetime. Many of his songs, of which he wrote around 200, have an enduring legacy and timelessness, allowing them to maintain relevancy to the present day. In fact, Foster helped popularize Verse-Chorus song form in American popular song 1., one of the most enduring and popular song forms of all time. The blending of timeless lyrics, enduring song forms, and elements of varied musical styles like opera and parlor songs, has allowed the power of Foster’s artistry to maintain popularity over 150 years after his death. While the details of much of his life are scant, his brother Morrison Foster wrote much about his brother and it’s through the help of these writings from which we can piece together the details of Stephen Foster’s life.

Born in Pennsylvania on the Fourth of July 1826, Foster was the youngest of nine siblings. His family was musical, but Stephen himself was largely self-taught. His brother Morrison Foster wrote, “He had but few teachers. Not only was musical instruction chiefly for females, but by the time Stephen was old enough to profit from lessons, his parents could ill afford them” (Emerson, 1997, p. 325). In childhood and as a young man, Foster learned to play many different instruments including flute, guitar, and piano. His brother Morrison wrote that as early as two years of age, Stephen would lay his sister Ann Eliza’s guitar on the floor “and pick out harmonies from it’s strings. He called it his ‘itty pisano’ (little piano)” (Emerson, 1997, p. 51). By the age of 9, Stephen was already pulled into the world of musical performance. While he didn’t perform regularly as an adult, he was considered a talented and engaging performer as a child. He performed “crude comic songs written in blackface dialect” (Emerson, 1997, p. 55). Blackface dialect is a lyrical style representing a blatant caricature of 19th century African Americans. With its inherent racist content, blackface is not a genre that has aged well, but at the time it was quite simply “in fashion” for songwriters. As we’ll see, Stephen Foster would write songs of his own using blackface dialect such as “Uncle Ned”.

In 19th century America, musical pursuits were generally regard as the province of women and children. As a teenager, Stephen seemed to lack an interest in anything except music, but was able to find male figures that gave him confidence to pursue his own musical path: Henry Kleber, a German immigrant and classically-trained music teacher and Dan Rice, a minstrel performer (Emerson, 1997, p. 100). By his twenties, Foster was struggling to find direction. Dropping out of college after one week and seemingly disinterested in standard career paths suggested to him by his brother Morrison, he worked menial warehouse jobs while writing songs of his own and, starting in 1844, publishing them (Emerson 1997). By this time, he had become too shy to perform publicly and composition became his primary artistic outlet. He spent time in Cincinnati in 1846 working as a bookkeeper. While there he had a chance to hear and absorb the music of African-Americans as the city was in Ohio, a state free of slavery. Musical and cultural exposure such as this played a role in the development of Foster’s songwriting in songs such as “Old Folks At Home”. Foster is alleged to have written the popular song after hearing enslaved boat workers singing a similar melody and words in New Orleans (Emerson, 1997, p. 121). He continued writing, publishing and organizing performances of his songs into the following year.

On September 11, 1847 Foster debuted his song “Oh! Susanna,” a song that would cement Foster as a household name. The song fit the mold for popular songs of the day with its seemingly silly lyrics in the blackface dialect. The lyrics are more complex, however. A mixture of light-heartedness, blatant racism, and a dreadful anxiety about technology and what it meant for the future, “Oh! Susanna” seemed to appeal to all sorts of listeners and improvised lyrics to the tune were developed to fit the lives of different people. For example, during the Gold Rush to California in 1848, the following verse was routinely sung to the tune of “Oh! Susanna” by travelers:

“Oh California! Thou Land of glittering dreams,

Where the yellow dust and diamond, boys,

Are found in all thy streams”

“Oh Susanna” was published in 1848 and was soon followed by approximately 30 di fferent arrangements by 16 different publishers, hinting at it’s popularity. It’s unclear if Foster was making any money at all from sales of the sheet music of “Oh! Susanna”. In fact, his brother Morrison wrote that Stephen gave “Oh! Susanna” to W.C. Peters for free, and the publisher subsequently made $10,000 off the song. Beyond the problems of making money, Foster was definitely making a name for himself.

Listening Examples 1.2

Eventually Foster fell in love with Jane McDowell, forever immortalized in his song “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair”. The couple married in 1850 and had one daughter. Stephen began developing a problem with alcohol during the course of the marriage, and the family shared a rented house with Stephen’s parents and adult siblings. These factors certainly caused strain and ultimately resulted in a separation between Stephen and Jane after a decade of marriage. Meanwhile, Foster’s music continued to be performed and published. He was using blackface dialect less and less, though leaving blackface behind meant he was going broke. Ken Emerson, author of the definitive book on Foster “Doo-dah!” (1997), examined Foster’s business ledger books of 1857, noting that the average annual return in royalties for a non-blackface song was $31.00, while the average return for a blackface song was $319.44, more than ten times that amount (Emerson p. 174).

By the following decade, Foster was again struggling to make enough money, and his songs became generally more lachrymose. His life ended in poverty at age 37, a result of an accidental wound. He had 38 cents in his pocket. This sad end stands in stark contrast to the fact that his music has ensured his artistic legacy, lasting over 150 years at this point, will continue to endure for some time to come.

Foster’s use of Verse-Chorus form is one feature that helps his music endure. Verse-Chorus is today the most common structure of popular songs. There are earlier examples of said form, such as the Scottish traditional tune “The Bonnie Banks of Loch Lomond” first published in 1841 and written by an unknown composer, but Foster’s regular use of the form and his subsequent influence on other composers helped the form endure. In song’s such as “Oh Susanna!” the chorus is simple and easy to remember.

Left is the sheet music from Foster’s song “Hard Times Come Again No More.”