9: The Baroque in France and England in the 1600s

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Introduction

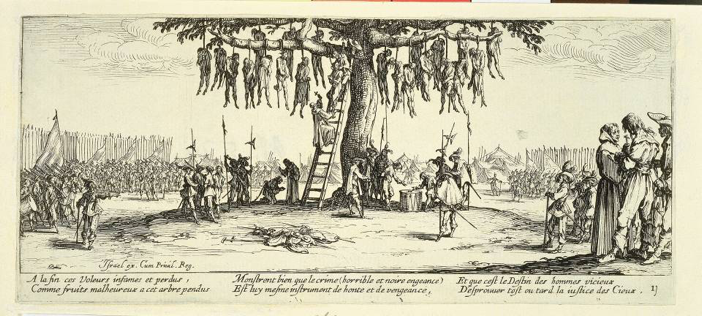

Wars and regional uprisings dominate the 1600s in France and England. Charles I is beheaded on charges of treason and France challenges England for world supremacy. Italy is still the area where art inspires, and artists come to study painting, sculpture, and architecture. The great works of the Italian Renaissance as well as the emerging themes of the Baroque such as dramatic lighting, theatricality, and movement are explored by a new generation of artists from north of the Alps. French artists travel to Rome and learn techniques they’ll bring back to Paris while regional artforms like miniatures will find a place in England. One individual, Louis XIV, will dominate the era and challenge Italy for the title of art center of Europe and the West. It is most fitting to begin the study of this region with a print from the Miseries of War by Jacques Callot. In a time of war, the most brutal and infamous of thieves and lawless criminals find justice in this engraving.

Hangman’s Tree, Jacques Callot 1633

https://collections.telfair.org/objects/7032/the-hangmans-tree

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459356

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/23112/the-hanging-plate-eleven-from-the-miseries-of-war

The Baroque in France

Joseph the Carpenter, Georges de La Tour 1642

Georges de La Tour paints an endearing image of Jesus with his father joseph, the carpenter. The lighting is pure Caravaggio, while the setting is Counter Reformation art meant to sentimentally tug at the viewer’s heart strings. The composition is focused on the dimly lit workspace of the carpenter and the helpfulness of the young Jesus who holds the illuminating torch, symbolizing his role of God on earth bringing light and salvation. At some point, de La Tour saw paintings or prints by Caravaggio and adopted this technique in his work. Not much is recorded or documented about de La Tour since he appears to have remained in his small community for most of his life.

https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1461.html

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436838

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103JY0

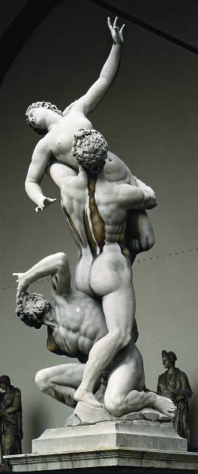

The Abduction of the Sabine Women, Nicolas Poussin 1633-1634

The Abduction of the Sabine Women, Nicolas Poussin 1630

The Abduction of the Sabine Women, by Nicolas Poussin demonstrates a new interest in classical themes. Poussin was a meticulous researcher of classical cultures, particularly Ancient Rome. He made small models of the architecture and drew sketches to work out the special aspects of his paintings. With The Abduction of the Sabine Women, we see him referencing the sculptural work of the Flemish sculptor who studied with Michelangelo and was active in Rome, Giovanni da Balogna (see above).

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pous/hd_pous.htm

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/nicolas-poussin

https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1798.html

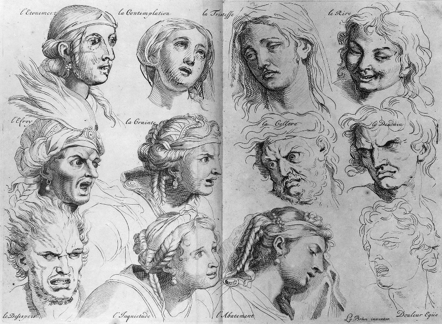

Charles Le Brun 1698

Charles Le Brun is instrumental in loving art and art education forward under the watchful stewardship of Louis XIV. His published works help establish a rigorous and academic approach to art education. Expressions and gestures of the head and face are featured in the drawings above. His work in two-dimensional art as well as architecture helped establish a consistent branding of images representing the French king’s court.

Portrait of Louis XIV, Hyacinthe Rigaud 1701

The portrait of Louis XIV counters the English portrait of Charles I, using the same posture and pose. Prior to his rise as king, Louis prided himself on his dancing and features his athletic legs prominently in this painting. With a diminutive height of just 5’ 4”, he used his own designed heeled shoes and tall wig to give the impression of one much taller in stature. The painting is impressive in size and detailed rendering of the sumptuous robes, massive sword, and classical setting with the ornate column in the background. Louis XIV uses artwork much as the Medici’s in the Renaissance to further his image and bolster his power and authority. This, of course, is nothing new and has been dome since antiquity through images of the pharaohs, Caesars, and other authoritarian rulers such as Darius and Xerxes in Persia. Make no mistake, Louis XIV is the consummate dictatorial ruler who controls everyone and everything around him. He controlled the publications and messaging in France through a micromanaging style and by coalescing his aristocratic court into one location outside of Paris at the Palace of Versailles. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/83/

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103RA8

https://smarthistory.org/rigaud-louis-xiv/

Versailles Louis Le Van and Jules Hardouin-Mansart 1669-1685

Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, Louis Le Van and Jules Hardouin-Mansart and Charles Le Brun 1678

Louis XIV has enormous wealth from the exploitation of far-flung colonies and through his war efforts. He uses this asset to prop up his own image and create his vision of a monarchy. Much of what he creates is flamboyant excess and opulence beyond comprehension. The cost of one mirror at that time was expensive, but to create an entire hall of mirrors is hard to fathom. This flamboyant style will usher in the final phase of the Baroque known as the Rococo.

East front of the Louvre, Paris, Louis Le Van Claude Perrault and Charles Le Brun 1667-1670

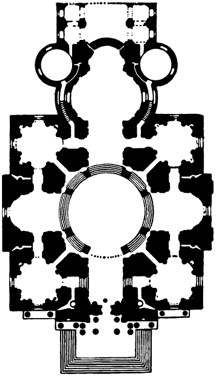

Church of the Invalides, Paris Jules Hardouin-Mansart 1677-1691

Bernini himself is brought to the court of Louis XIV to help design the façade of the Louvre. Unfortunately, his designs are not well received by the king and a committee of trusted artists and academics is formed. Perrault is likely the main influencer within the group, but Le Van and Le Brun have input into the design as well. The East façade of the Louvre uses the first floor as the visual foundation with the subsequent floors represented as a classical temple with triglyphs and metopes becoming the top stone barrier at the roof’s edge. Double, paired fluted Corinthian columns adorn the façade as well linking the design to Michelangelo, Borromini, and other architects.

https://smarthistory.org/louvre-colonnade/

https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/charles-perrault

https://www.unjourdeplusaparis.com/en/paris-culture/colonnade-perrault-louvre

The Baroque in England

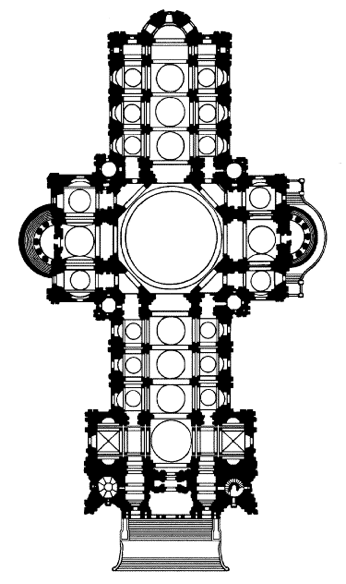

St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, Sir Christopher Wren 1675-1710

To prevent civil uprisings on the streets of Paris, Louis XIV must house the war wounded away from the city. He commissions Jules Hardouin-Mansart to design a hospital/church to serve this purpose. The Church of the Invalides is a square Baroque design with elements borrowed from the dome of Saint Peter’s, as well as the double temple front style of Borromini. The king can access the building through a private chapel with balcony where he can view the wounded below.

https://www.musee-armee.fr/en/your-visit/museum-spaces/dome-des-invalides-tomb-of-napoleon-i.html