2: International Style

- Page ID

- 219604

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)International Style

Overview:

The Gothic Style of art and architecture spread across Europe replacing the Romanesque style. The greatest achievements of this era are what have been termed a white garment of churches spread across medieval Europe. Foremost amongst these structures are the great Gothic cathedrals, particularly those built in France. Another area of art that flourished in the late Gothic era is sculpture, particularly the works of artists working for the duke of Burgundy in Dijon. Sculptors Claus Sluter, from the Netherlands, is one of these artists. His work is of exceptional quality and far exceeds the earlier sculptural work of the European Medieval sculptors. His sculptures are mainly functional works such as The Moses Well. With this work, he creates the first genuine portrait since antiquity. It also would have been painted with polychromy making it even more realistic in appearance.

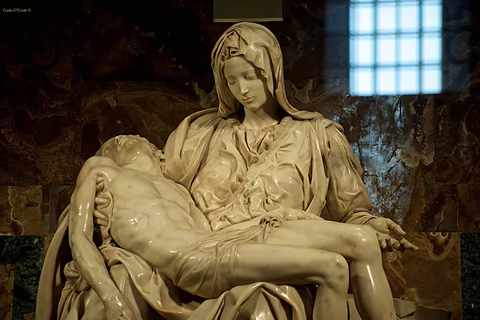

Another sculpture of significance is the Roettgen Pietà from the early 1300s. This sorrowful image is meant to be experienced on a personal level enhancing Christian prayer and devotion. The term for these highly emotional works is Adachtsbild. Works like this will become instrumental in the development of related Renaissance sculpture such as the famous Pietà by Michelangelo.

Two sculptors who help bring in the Gothic Style from the north into Italy are the Giovanni and Nicola Pisano. Giovanni sculpts a Nativity in the years 1259-1260. It is more typical of the Gothic sculpture appearing on the walls of Gothic cathedrals. The sculptural work with packed space becomes integrated into the architectural design. The work of Giovanni’s son Nicola, shows a movement away from the traditional Gothic style with a disembodiment of the figural elements. There is a tangible three-dimensional space around the forms to assist in the visual storytelling and to better delineate the drapery and details of the figures. Nicola’s Nativity from 1302-1310 is a great example of this movement towards classicism.

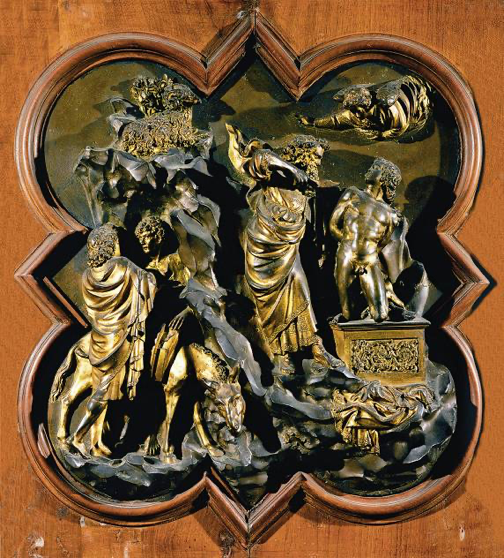

The culmination of this Gothic classicism is found in the sculptural works of Lorenzo Ghiberti in what is termed the International Style Securing the commission of the bronze baptistry doors of Florence Cathedral, after winning over a very competitive submission by Filippo Brunelleschi, Ghiberti spent 27 years completing this masterpiece. A masterpiece that in many ways, helps usher in the Florentine (Italian) Renaissance.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Christian Europe struggled to survive with a turning point around the year 1,000 CE. For the next 400 years, Christian Europe continued to grow and by the time of the Italian Renaissance in the year 1400 CE, the pieces were in place for something monumental. All of the ingredients were there for a revolution – money, ambition, talent, and enough political stability to sustain and propel the intellectual and artistic movements forward.

The art and architecture of this era are in part the result of an intellectual movement termed Humanism. It is a move towards the study of the Humanities in the intellectual centers of Europe, particularly France. The writings of the Italian poet Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), known as Petrarch, helped revive many of the classics and restore them to the original Latin and Greek forms. He emphasized the humane letters (study of Humanities) rather than the divine letters of Christendom. To study outside the boundaries of Christian theology was often a dangerous proposition, particularly if the local clergy and politicians were not supportive. The Pope was still the ultimate authority and considered infallible to the Roman Catholic populace. Under the Pope, the Cardinals would have considerable say in the teachings and studies taking place in the Italian city-states, including Florence. Petrarch went against this powerful religious and political force to conclude that the age of faith exhibited during the Middle Ages was in fact a time of darkness and that the Greco-Roman pagans were in fact the more enlightened civilization. This was again a dangerous path that could lead to death by execution, but one that will come to epitomize the direction of the liberal city-state of Florence and its cultural leaders. We will find echoes of Petrarch’s humanism in the search for ancient knowledge by those who rise to Florentine power in the 1400s, particularly the Medici family and those artists working under their patronage. This movement is at the core of the rebirth of scientific and artistic inquiry and study – the Renaissance (literally meaning rebirth).