In this section I will analyze a real-life argument—an excerpt from President Obama’s September 10, 2013 speech on Syria. I will use the concepts and techniques that have been introduced in this chapter to analyze and evaluate Obama’s argument. It is important to realize that regardless of one’s views— whether one agrees with Obama or not—one can still analyze the structure of the argument and even evaluate it by applying the informal test of validity to the reconstructed argument in standard form. I will present the excerpt of Obama’s speech and then set to work analyzing the argument it contains. In addition to creating the excerpt, the only addition I have made to the speech is numbering each paragraph with Roman numerals for ease of referring to specific places in my analysis of the argument.

I. My fellow Americans, tonight I want to talk to you about Syria, why it matters and where we go from here. Over the past two years, what began as a series of peaceful protests against the repressive regime of Bashar al-Assad has turned into a brutal civil war. Over a hundred thousand people have been killed. Millions have fled the country. In that time, America has worked with allies to provide humanitarian support, to help the moderate opposition and to shape a political settlement.

II. But I have resisted calls for military action because we cannot resolve someone else's civil war through force, particularly after a decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

III. The situation profoundly changed, though, on Aug. 21st, when Assad's government gassed to death over a thousand people, including hundreds of children. The images from this massacre are sickening, men, women, children lying in rows, killed by poison gas, others foaming at the mouth, gasping for breath, a father clutching his dead children, imploring them to get up and walk. On that terrible night, the world saw in gruesome detail the terrible nature of chemical weapons and why the overwhelming majority of humanity has declared them off limits, a crime against humanity and a violation of the laws of war.

IV. This was not always the case. In World War I, American GIs were among the many thousands killed by deadly gas in the trenches of Europe. In World War II, the Nazis used gas to inflict the horror of the Holocaust. Because these weapons can kill on a mass scale, with no distinction between soldier and infant, the civilized world has spent a century working to ban them. And in 1997, the United States Senate overwhelmingly approved an international agreement prohibiting the use of chemical weapons, now joined by 189 governments that represent 98 percent of humanity.

V. On Aug. 21st, these basic rules were violated, along with our sense of common humanity.

VI. No one disputes that chemical weapons were used in Syria. The world saw thousands of videos, cellphone pictures and social media accounts from the attack. And humanitarian organizations told stories of hospitals packed with people who had symptoms of poison gas.

VII. Moreover, we know the Assad regime was responsible. In the days leading up to Aug. 21st, we know that Assad's chemical weapons personnel prepared for an attack near an area where they mix sarin gas. They distributed gas masks to their troops. Then they fired rockets from a regime-controlled area into 11 neighborhoods that the regime has been trying to wipe clear of opposition forces.

VIII. Shortly after those rockets landed, the gas spread, and hospitals filled with the dying and the wounded. We know senior figures in Assad's military machine reviewed the results of the attack. And the regime increased their shelling of the same neighborhoods in the days that followed. We've also studied samples of blood and hair from people at the site that tested positive for sarin.

IX. When dictators commit atrocities, they depend upon the world to look the other way until those horrifying pictures fade from memory. But these things happened. The facts cannot be denied.

X. The question now is what the United States of America and the international community is prepared to do about it, because what happened to those people, to those children, is not only a violation of international law, it's also a danger to our security.

XI. Let me explain why. If we fail to act, the Assad regime will see no reason to stop using chemical weapons.

XII. As the ban against these weapons erodes, other tyrants will have no reason to think twice about acquiring poison gas and using them. Over time our troops would again face the prospect of chemical warfare on the battlefield, and it could be easier for terrorist organizations to obtain these weapons and to use them to attack civilians.

XIII. If fighting spills beyond Syria's borders, these weapons could threaten allies like Turkey, Jordan and Israel.

XIV. And a failure to stand against the use of chemical weapons would weaken prohibitions against other weapons of mass destruction and embolden Assad's ally, Iran, which must decide whether to ignore international law by building a nuclear weapon or to take a more peaceful path.

XV. This is not a world we should accept. This is what's at stake. And that is why, after careful deliberation, I determined that it is in the national security interests of the United States to respond to the Assad regime's use of chemical weapons through a targeted military strike. The purpose of this strike would be to deter Assad from using chemical weapons, to degrade his regime's ability to use them and to make clear to the world that we will not tolerate their use. That's my judgment as commander in chief.

The first question to ask yourself is: What is the main point or conclusion of this speech? What conclusion is Obama trying to argue for? This is no simple question and in fact requires a good level of reading comprehension in order to answer it correctly. One of the things to look for is conclusion or premise indicators (section 1.2). There are numerous conclusion indicators in the speech, which is why you cannot simply mindlessly look for them and then assume the first one you find is the conclusion. Rather, you must rely on your comprehension of the speech to truly find the main conclusion. If you carefully read the speech, it is clear that Obama is trying to convince the American public of the necessity of taking military action against the Assad regime in Syria. So the conclusion is going to have to have something to do with that. One clear statement of what looks like a main conclusion comes in paragraph 15 where Obama says:

And that is why, after careful deliberation, I determined that it is in the national security interests of the United States to respond to the Assad regime's use of chemical weapons through a targeted military strike.

The phrase, “that is why,” is a conclusion indicator which introduces the main conclusion. Here is my paraphrase of that conclusion:

Main conclusion: It is in the national security interests of the United States to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons with military force.

Before Obama argues for this main conclusion, however, he gives an argument for the claim that Assad did use chemical weapons on his own civilians. This is what is happening in paragraphs 1-9 of the speech. The reasons he gives for how we know that Assad used chemical weapons include:

- images of the destruction of women and children (paragraph VI)

- humanitarian organizations’ stories of hospitals full of civilians suffering from symptoms of exposure to chemical weapons (paragraph VI)

- knowledge that Assad’s chemical weapons experts were at a site where sarin gas is mixed just a few days before the attack (paragraph VII)

- the fact that Assad distributed gas masks to his troops (paragraph VII)

- the fact that Assad’s forces fired rockets into neighborhoods where there were opposition forces (paragraph VII)

- senior military officers in Assad’s regime reviewed results of the attack(paragraph VIII)

- the fact that sarin was found in blood and hair samples from people at the site of the attack (paragraph VIII)

These premises do indeed provide support for the conclusion that Assad used chemical weapons on civilians, but it is probably best to see this argument as a strong inductive argument, rather than a deductive argument. The evidence strongly supports, but does not compel, the conclusion that Assad was responsible. For example, even if all these facts were true, it could be that some other entity was trying to set Assad up. Thus, this first subargument should be taken as a strong inductive argument (assuming the premises are true, of course), since the truth of the premises would increase the probability that the conclusion is true, but not make the conclusion absolutely certain.

Although Obama does give an argument for the claim that Assad carried out chemical weapon attacks on civilians, that is simply an assumption of the main argument. Moreover, although the conclusion of the main argument is the one I have indicated above, I think there is another, intermediate conclusion that Obama argues for more directly and that is that if we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, then our own national security will be put at risk. We can clearly see this conclusion stated in paragraph 10. Moreover, the very next phrase in paragraph 11 is a premise indicator, “let me explain why.” Obama goes on to offer reasons for why failing to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons would be a danger to our national security. Thus, the conclusion Obama argues more directly for is:

Intermediate conclusion: A failure to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons is a threat to our national security.

So, if that is the conclusion that Obama argues for most directly, what are the premises that support it? Obama gives several in paragraphs 11-14:

A. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, then Assad’s regime will continue using them with impunity. (paragraph 11)

B. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, this will effectively erode the ban on them. (implicit in paragraph 12)

C. If the ban on chemical weapons erodes, then other tyrants will be more likely to attain and use them. (paragraph 12)

D. If other tyrants attain and use chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield (paragraph 12)

E. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons and if fighting spills beyond Syrian borders, our allies could face these chemical weapons. (paragraph 13)

F. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, it will weaken prohibitions on other weapons of mass destruction. (paragraph 14)

G. If prohibitions on other weapons of mass destruction are weakened, this will embolden Assad’s ally, Iran, to develop a nuclear program. (paragraph 14)

I have tried to make explicit each step of the reasoning, much of which Obama makes explicit himself (e.g., premises A-D). The main threats to national security that failing to respond to Assad would engender, according to Obama, are that U.S. troops and U.S. allies could be put in danger of facing chemical weapons and that Iran would be emboldened to develop a nuclear program. There is a missing premise that is being relied upon for these premises to validly imply the conclusion. Here is a hint as to what that missing premise is: Are all of these things truly a threat to national security? For example, how is Iran having a nuclear program a threat to our national security? It seems there must be an implicit premise—not yet stated—that is to the effect that all of these things are threats to national security. Here is one way of construing that missing premise:

Missing premise 1: An increased likelihood of U.S. troops or allies facing chemical weapons on the battlefield or Iran becoming emboldened to develop a nuclear program are all threats to U.S. national security interests.

We can also make explicit within the standard form argument other intermediate conclusions that follow from the stated premises. Although we don’t have to do this, it can be a helpful thing to do when an argument contains multiple premises. For example, we could explicitly state the conclusion that follows from the four conditional statements that are the first four premises:

1. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, then Assad’s regime will continue using them with impunity.

2. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, this will effectively erode the ban on them.

3. If the ban on chemical weapons erodes, then other tyrants will be more likely to attain and use them.

4. If other tyrants attain and use chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield.

5. Therefore, if we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield. (from 1-4)

Premise 5 is an intermediate conclusion that makes explicit what follows from premises 1-4 (which I have represented using parentheses after that intermediate conclusion). We can do the same thing with the inference that follows from premises, 1, 7, and 8 (i.e., line 9). If we add in our missing premises then we have a reconstructed argument for what I earlier called the “intermediate conclusion” (i.e., the one that Obama most directly argues for):

1. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, then Assad’s regime will continue using them with impunity.

2. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, this will effectively erode the ban on them.

3. If the ban on chemical weapons erodes, then other tyrants will be more likely to attain and use them.

4. If other tyrants attain and use chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield.

5. Therefore, if we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield. (from 1-4)

6. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons and if fighting spills beyond Syrian borders, our allies could face these chemical weapons.

7. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, it will weaken prohibitions on other weapons of mass destruction.

8. If prohibitions on other weapons of mass destruction are weakened, this will embolden Assad’s ally, Iran, to develop a nuclear program.

9. Therefore, if we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, this will embolden Assad’s ally, Iran, to develop a nuclear program. (from 1, 7-8)

10. An increased likelihood of U.S. troops or allies facing chemical weapons on the battlefield or Iran becoming emboldened to develop a nuclear program are threats to U.S. national security interests.

11. Therefore, a failure to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons is a threat to our national security. (from 5, 6, 9, 10)

As always, in this standard form argument I’ve listed in parentheses after the relevant statements which statements those statements follow from. The only thing now missing is how we get from this intermediate conclusion to what I earlier called the main conclusion. The main conclusion (i.e., that it is in national

security interests to respond to Assad with military force) might be thought to follow directly. But it doesn’t. It seems that Obama is relying on yet another unstated assumption. Consider: even if it is true that we should respond to a threat to our national security, it doesn’t follow that we should respond with military force. For example, maybe we could respond with certain kinds of economic sanctions that would force the country to submit to our will. Furthermore, maybe there are some security threats such that responding to them with military force would only create further, and worse, security threats. Presumably we wouldn’t want our response to a security threat to create even bigger security threats. For these reasons, we can see that Obama’s argument, if it is to be valid, also relies on missing premises such as these:

Missing premise 2: The only way that the United States can adequately respond to the security threat that Assad poses is by military force.

Missing premise 3: It is in the national security interests of the United States to respond adequately to any national security threat.

These are big assumptions and they may very well turn out to be mistaken. Nevertheless, it is important to see that the main conclusion Obama argues for depends on these missing premises—premises that he never explicitly states in his argument. So here is the final, reconstructed argument in standard form. I have italicized each missing premise or intermediate conclusion that I have added but that wasn’t explicitly stated in Obama’s argument.

1. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, then Assad’s regime will continue using them with impunity.

2. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, this will effectively erode the ban on them.

3. If the ban on chemical weapons erodes, then other tyrants will be more likely to attain and use them.

4. If other tyrants attain and use chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield.

5. Therefore, if we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, U.S. troops will be more likely to face chemical weapons on the battlefield. (from 1-4)

6. If we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons and if fighting spills beyond Syrian borders, our allies could face these chemical weapons.

7. If Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons with impunity, it will weaken prohibitions on other weapons of mass destruction.

8. If prohibitions on other weapons of mass destruction are weakened, this will embolden Assad’s ally, Iran, to develop a nuclear program.

9. Therefore, if we don’t respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, this will embolden Assad’s ally, Iran, to develop a nuclear program. (from 1, 7-8)

10. An increased likelihood of U.S. troops or allies facing chemical weapons on the battlefield or Iran becoming emboldened to develop a nuclear program are threats to U.S. national security interests.

11. Therefore, a failure to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons is a threat to our national security. (from 5, 6, 9, 10)

12. The only way that the United States can adequately respond to the security threat that Assad poses is by military force.

13. It is in the national security interests of the United States to respond adequately to any national security threat.

14. Therefore, it is in the national security interests of the United States to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons with military force. (from 11-13)

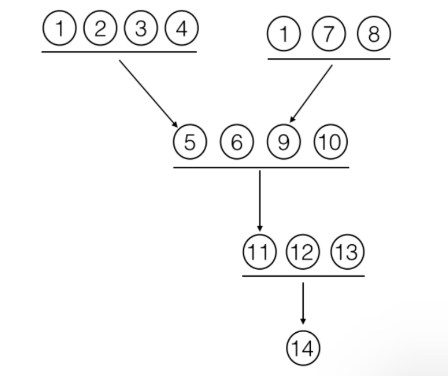

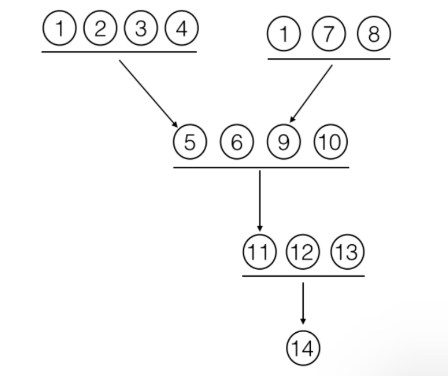

In addition to showing the structure of the argument by use of parentheses which show which statements follow from which, we can also diagram the arguments spatially as we did in section 1.4 like this:

This is just another way of representing what I have already represented in the standard form argument, using parentheses to describe the structure. As is perhaps even clearer in the spatial representation of the argument’s structure, this argument is complex in that it has numerous subarguments. So while statement 11 is a premise of the main argument for the main conclusion (statement 14), statement 11 is also itself a conclusion of a subargument whose premises are statements 5, 6, 9, and 10. And although statement 9 is a premise in that argument, it itself is a conclusion of yet another subargument whose premises are statements 1, 7 and 8. Almost any interesting argument will be complex in this way, with further subarguments in support of the premises of the main argument. This chapter has provided you the tools to be able to reconstruct arguments like these. As we have seen, there is much to consider in reconstructing a complex argument. As with any skill, a true mastery of it requires lots of practice. In many ways, this is a skill that is more like an art than a science. The next chapter will introduce you to some basic formal logic, which is perhaps more like a science than an art.