6.4: Types of Argument Approaches

- Page ID

- 170525

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)You will have exercises at the end of the chapter to apply these argument approaches in your writing.

Aristotelian / Classical Western Argument Approach

The source from which the Classical Western Argument approach is found from the Greek philosopher, Aristotle. Aristotle, an individual that condoned and supported slavery and basically placed restrictive value on certain individuals and groups within a given society, presented a structure on how to present an effective argument to Western Civilization that was adopted by and saturated into English departments everywhere; his method is the fundamental structure on how argument essays are taught in today’s schools, colleges and universities. The structure is simple:

A classical Western argument is used to persuade a group of people of the validity of an argument and/or reveal the truths that define or affect the argument. This is a basic type of persuasive argument and typically includes five different components: an introduction, narration, confirmation, refutation, and a conclusion.

Classical arguments are often used when an individual or group wants to be more aggressive or direct, or when someone wants to establish power with another individual or group. Many people who use the classical argument wrap up their conclusion by incorporating appeals to the audience's motivations, values and feelings to help them identify with the argument.

Let us take a look at what the structure looks like below: (Can the type be bigger?)

|

|

|

Toulmin Argument Approach

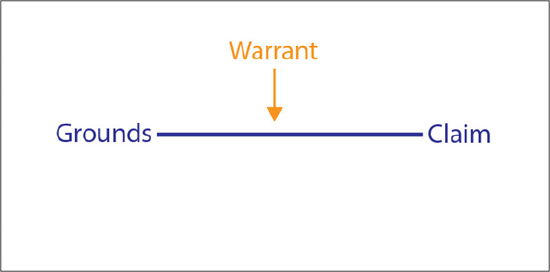

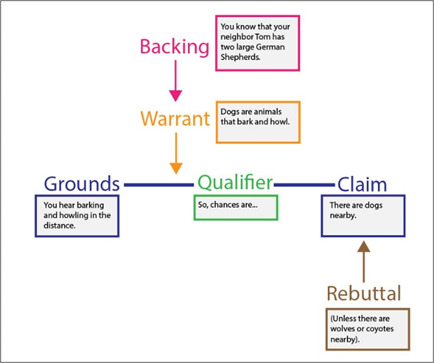

Developed by philosopher Stephen E. Toulmin, the Toulmin method is a style of argumentation that breaks arguments down into six component parts: claim, grounds, warrant, qualifier, rebuttal, and backing. In Toulmin’s method, every argument begins with three fundamental parts: the claim, the grounds, and the warrant.

A claim is the assertion that authors would like to prove to their audience. It is, in other words, the main argument.

The grounds of an argument are the evidence and facts that help support the claim.

Finally, the warrant, which is either implied or stated explicitly, is the assumption that links the grounds to the claim.

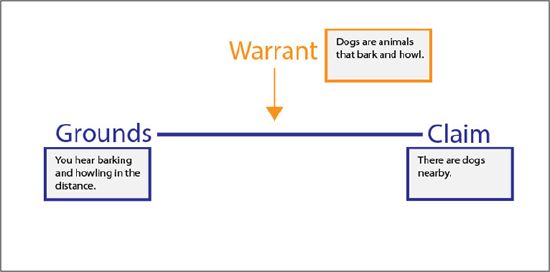

For example, if you argue that there are dogs nearby:

In this example, in order to assert the claim that a dog is nearby, we provide evidence and specific facts—or the grounds—by acknowledging that we hear barking and howling. Since we know that dogs bark and howl (i.e., since we have a warrant) we can assume that a dog is nearby.

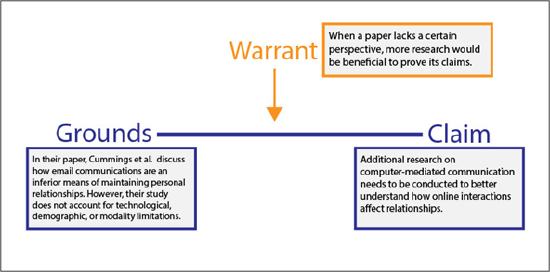

Now, let’s try a more academic approach. Let’s say that you are writing a paper on how more research needs to be done on the way that computer-mediated communication influences online and offline relationships.

In this case, to assert the claim that additional research needs to be made on how online communication affects relationships, the author shows how the original article needs to account for technological, demographic, and modality limitations in the study. Since we know that when a study lacks a perspective, it would be beneficial to do more research (i.e., we have a warrant), it would be safe to assume that more research should be conducted (i.e. the claim).

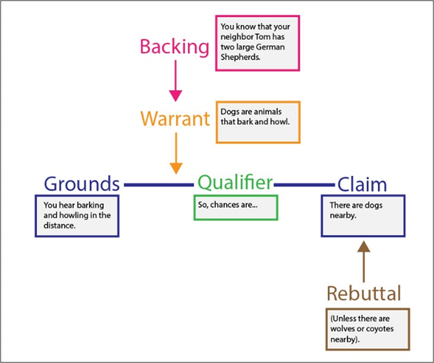

The other three elements—backing, qualifier, and rebuttal—are not fundamental to a Toulmin argument, but may be added as necessary. Using these elements wisely can help writers construct full, nuanced arguments.

Backing refers to any additional support of the warrant. In many cases, the warrant is implied, and therefore the backing provides support for the warrant by giving a specific example that justifies the warrant.

The qualifier shows that a claim may not be true in all circumstances. Words like “presumably,” “some,” and “many” help your audience understand that you know there are instances where your claim may not be correct.

The rebuttal is an acknowledgement of another valid view of the situation.

Including a qualifier or a rebuttal in an argument helps build your ethos, or credibility. When you acknowledge that your view isn’t always true or when you provide multiple views of a situation, you build an image of a careful, unbiased thinker, rather than of someone blindly pushing for a single interpretation of the situation.

Let us take a look at an example:

We can also add these components to our academic paper example:

Note that, in addition to Stephen Toulmin’s Uses of Argument, students and instructors may find it useful to consult the article “Using Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation” by Joan Karbach for more information (owl.purdue.edu).

The Rogerian Argument Approach

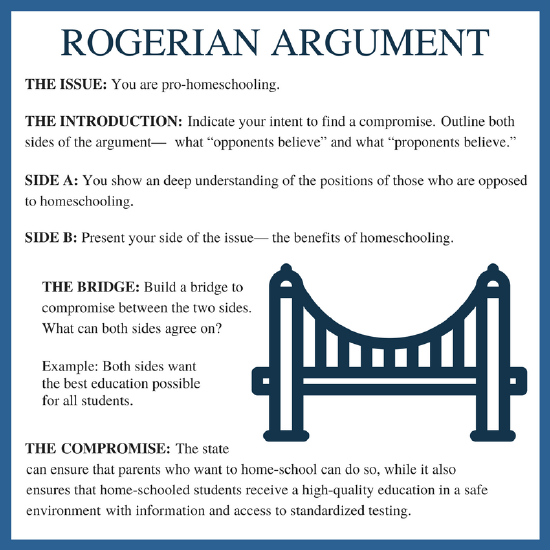

A Rogerian argument is an argument used to determine the best possible solution to a particular issue based on the interests and needs of all parties involved. This type of argument is used to help those with opposing viewpoints reach a common ground by allowing them to look at a situation from a different perspective. In a Rogerian argument, both parties acknowledge the opposition and build trust by identifying each other’s merit.

Let us take a look at how the Rogerian argument is structured:

Rhetorical Structure: The Rogerian Argument

The Rogerian argument is a rhetorical form that includes both sides of a debate, representing the opposition’s opinion while systematically refuting their claims. Therefore, this rhetorical structure is best used for topics that are controversial, entrenched, or emotional, since it is difficult to persuade an opinionated audience if they don’t feel their voice has been heard.

Image by viva.pressbooks.pub

Image by viva.pressbooks.pub

The Aristotelian/Classical Western Argument Approach Image https://luthersem.libguides.com/ld.p...nt_id=34720376

The Rogerian Argument Approach Image https://viva.pressbooks.pub/letsgetw...rian-argument/

The Toulmin Argument Approach Image https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_w...05Toulmin5.jpg