7.2: Early Medieval Empires of India (550 CE – 1200 CE)

- Page ID

- 219993

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The golden age of ancient India, known as the early medieval period, commenced around 550 following the decline of the Gupta Empire. Several smaller empires, like the Pala Empire (7.2.1) and the Chola Empire (7.2.2) , emerged in the region throughout this era. These empires were governed by diverse dynasties and leaders who would often engage in conflicts with each other but also occasionally extend support to their neighboring territories.Historians believe there were twenty to forty commands during this time, each creating distinct events; for example, in the 6th century, the Rashtrakuta dynasty built the caves at Ellora. The Pala Empire had the last monarch to support Buddhism, and the Chola Empire in the southern region increased its influence in South Asia.

Each dynasty focused on different objectives, including geographical and religious concentrations. Other religions were generally tolerated, with Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism all existing simultaneously and thriving as their entities. The architecture driven by each religion was similar, and some rulers set standards for all to follow. Art was also based on religion and reflected in the temple buildings, carvings, and statues. Political ideology was not the primary force, and designs and standards were usually based on language, literature, and religious practices.

The idea of calling this period medieval is controversial. The concept is based on medieval times in Europe with plagues, wars, religious battles, and general darkness of spirit. In India, the period was one of progress, creative art, and poetic literature. The Early Medieval Period in India was a term to identify different dynasties and empires occurring simultaneously or in succession. So, the Early Medieval Period started after the Gupta Empire and the country was split into groups uninterested in unification. Unification developed larger territories in the Late Medieval Period, beginning the Mughal Empire in 1526.

Ellora Caves

The Ellora Caves extended the concept of carving rock caves into religious monasteries and temples. One of the largest cave installations in the world is in Maharashtra, and it supports three different religions. Caves 1 to 12 are Buddhist, 13 to 29 are Hindu, and caves 30 to 34 are Jain. The caves were constructed over a long period from 600 CE to 1000 CE. Cave 16 holds the Kailasha temple and is the largest single building in the world carved from rock. The temples, carvings, and sculptures were cut from the rock, along with numerous monasteries supporting the different religions. Over one hundred caves were carved out of the rock mountain. Historians believe people carved so many caves because the rock exfoliated in layers, and the rock was in response to cutting with a chisel. The site was located by multiple streams forming waterfalls and ponds and providing easy access to water. The caves were located by the trade routes and were places for pilgrims and travelers to stay. Wealthy patrons frequently funded construction for some parts of a cave, helping to create a contemplative environment.

Buddhist Cave 10

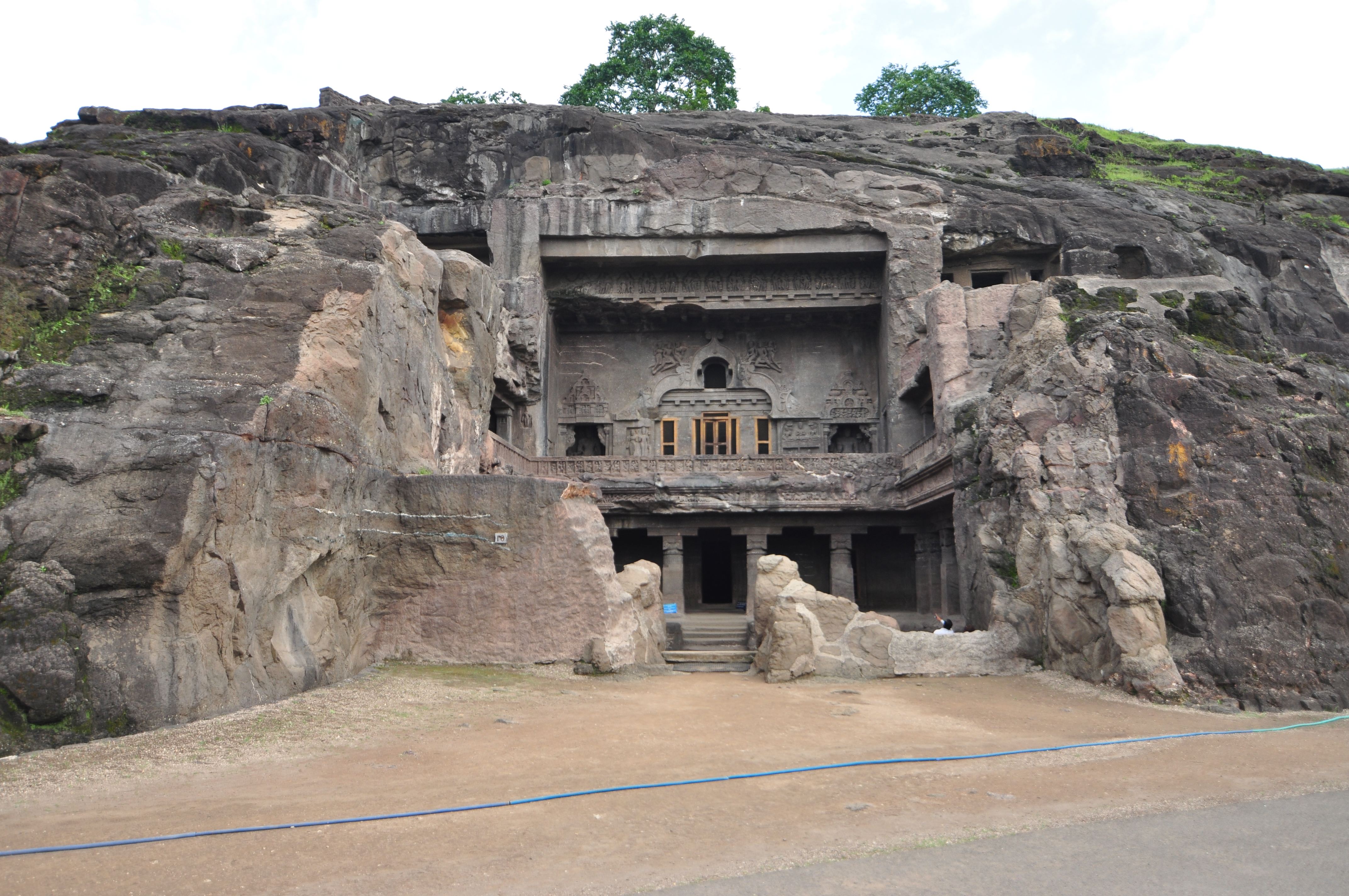

Of the twelve Buddhist caves, eleven were viharas or monasteries. Constructed between 630 CE and 730 CE, the facilities had multiple stories and included halls for prayer, living and sleeping areas, and kitchens for cooking. Sculptures were placed throughout the spaces. In Cave 10, the prayer hall (7.2.3), the entrance was multi-storied and elaborately carved with religious images, pillars, and balconies. Inside the prayer hall (7.2.4), the rock was carved to resemble a cathedral. The cave was called the "Carpenter's Cave" because the beams in the ceiling were finished to look like wooden beams. At the end of the hall was a stupa with an immense image of the Buddha carved on the front of the stupa. The Buddha is seated and appears to be preaching while Bodhisattvas flank him with a Bodhi tree behind him. Above the columns are relief carvings (7.2.5) representing male and female deities or entertainers, dancers, and musicians.

Buddhist Caves 11 and 12

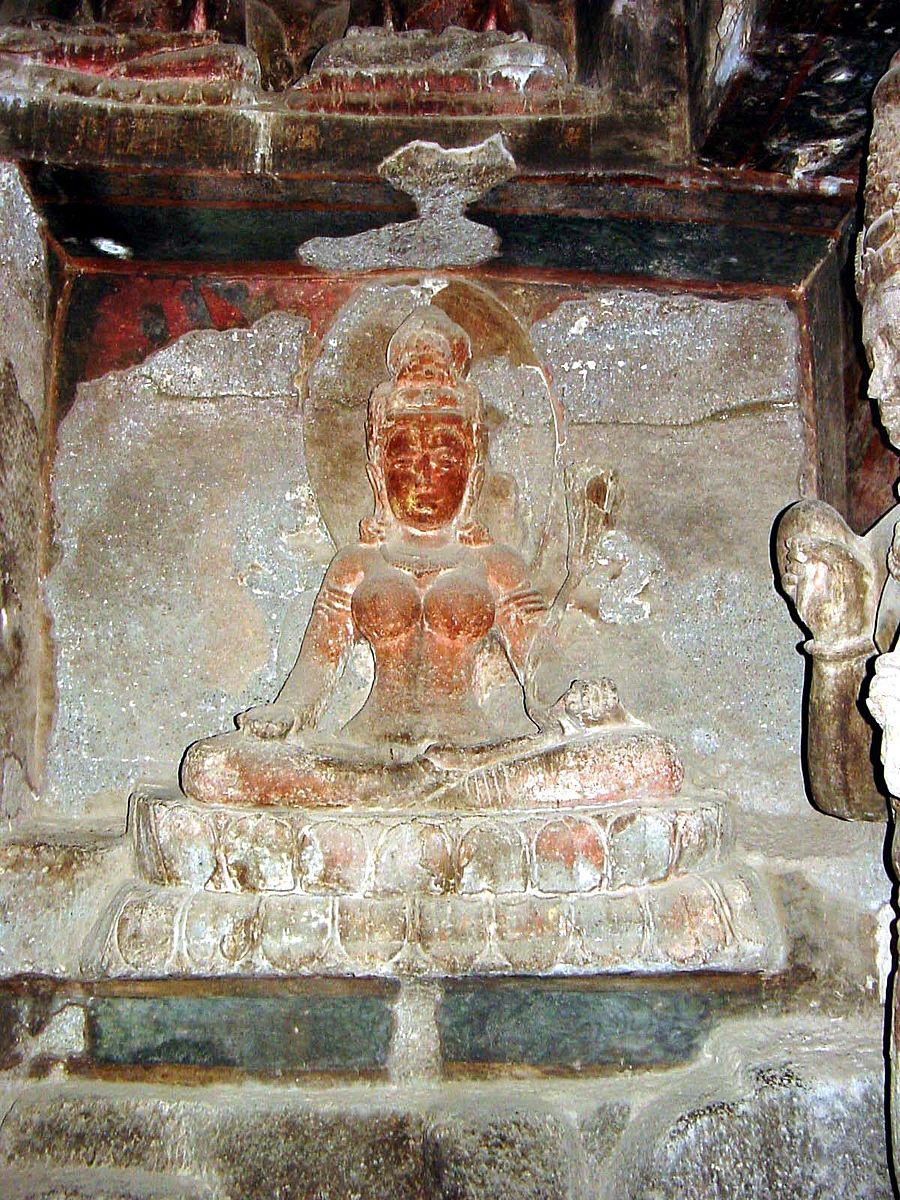

Caves 11 and 12 are the two biggest Buddhist monasteries. The three-storied caves look alike, although Cave 11 (7.2.6) is open on one side to the outside. Cave 12 has an immense rock wall blocking almost all of the exterior. The two monastery caves had large halls for working or meditation and many cells for sleeping or quiet contemplation. The viharas had multiple sculptures of Buddha and images of numerous goddesses. In Cave 12, the goddess (7.2.7) and the surrounding area were painted; only traces remain now. Goddess iconography was typical in this period, and many of the goddesses in the Buddhist caves may have been influenced by synergy with the other religions.

Hindu Cave 16

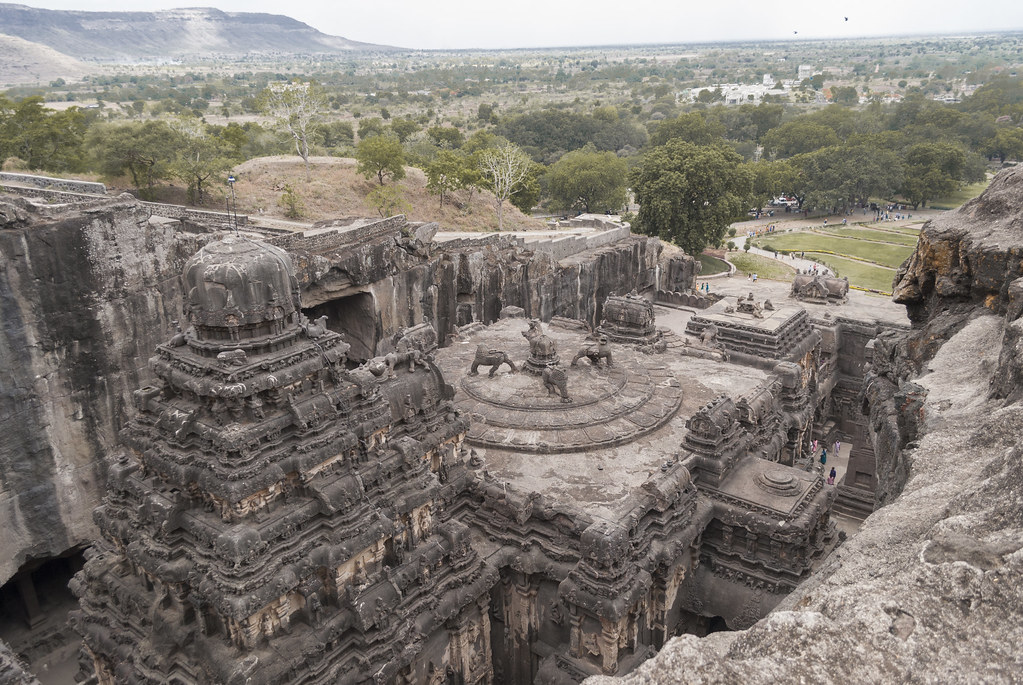

When the Hindu caves were carved in the 6th to 8th centuries, Cave 16 was the last to be constructed and was the most extensive cave. The cave is considered one of the most spectacular caving in the world of a religious facility because of its scale, complexity, construction, and sculptures. The multitude of freestanding sculptures is vast; life-sized elephants, lions, and enormous pillars are in the courtyard. The other caves on the site were caved inside the basalt rock; however, Cave 16 was carved inside, and the external sections were also carved to create the standing Kailasa Temple (7.2.8). The temple was made from top to bottom instead of the usual bottom to top. It was easier to carve from the top and let the chunks of rock roll downhill instead of moving the rock from inside. However, where the tons of stone went is unknown as there aren't any rock piles in the area. The temple is 91.4 meters long and 53.3 meters wide, and this massive structure was built with only hammers and chisels.

The roof view (7.2.9) shows the unique temple and other facility parts, demonstrating how the monolithic stone was laboriously carved to create the complex building. The cave's opening had two levels and walkways (7.2.10) with live-sized elephants lining the entry. The elephants were cut directly from the existing rock and remain unmovable as part of the natural stone.

The cave is filled with relief carvings (7.2.11) flanking the walkways and Entrance with figures dedicated to Shiva. In this carving, the multi-armed Ravana is shaking Mount Kailash with Shiva seated above and only using the pressure of his toe to trample Ravana. The Ramayana panel (7.2.12) is composed of seven rocks with different scenes depicting mythological stories. It starts with Rama's departure from Ayodhya and ends with the army of monkeys building a bridge. "Through the techniques of enlarging and foreshortening, of deep and shallow incisions, the major and minor characters are brought alive."[1] The Ramayana panel was located in a corner on the ground floor.

Jain Cave 32

In the 9th century, the Jain caves were the last set to be constructed. Cave 32 had two stories and was entered into a large court through an ornately carved entryway opening (7.2.13). An enormous elephant (7.2.14) guards the doorway on one side and a monolithic pedestal on the other. The entryway is crowned by four images at each corner facing the cardinal directions. Inside are multiple shrines, many of which are dedicated to Mahavira. The pillars are also decorated with elaborate stone carvings. The bottom story in the cave was unfinished, and most of the work was seen on the second floor, also the place of worship. Located in the back of the shrine is the immense carving of Siddhaika Yakshini (goddess of fertility) (7.2.15). She is seated on a lion in the shade of a mango tree, accompanied by her attendants. The other carving depicts Matanga Yaksha (god of prosperity) (7.2.16) sitting on an elephant and underneath a banyan tree. There were forty-eight Yakshas and Yakshinis, all very similar as they were the instructors for the Tirthankara.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=836&height=627)

.jpg?revision=1)

These 34 monasteries and temples, extending over more than 2 km, were dug side by side in the wall of a high basalt cliff, not far from Aurangabad, in Maharashtra. Ellora, with its uninterrupted sequence of monuments dating from A.D. 600 to 1000, brings the civilization of ancient India to life. Not only is the Ellora complex a unique artistic creation and a technological exploit but, with its sanctuaries devoted to Buddhism and Hinduism.

Additional text/introduction.

Khajuraho Group of Monuments

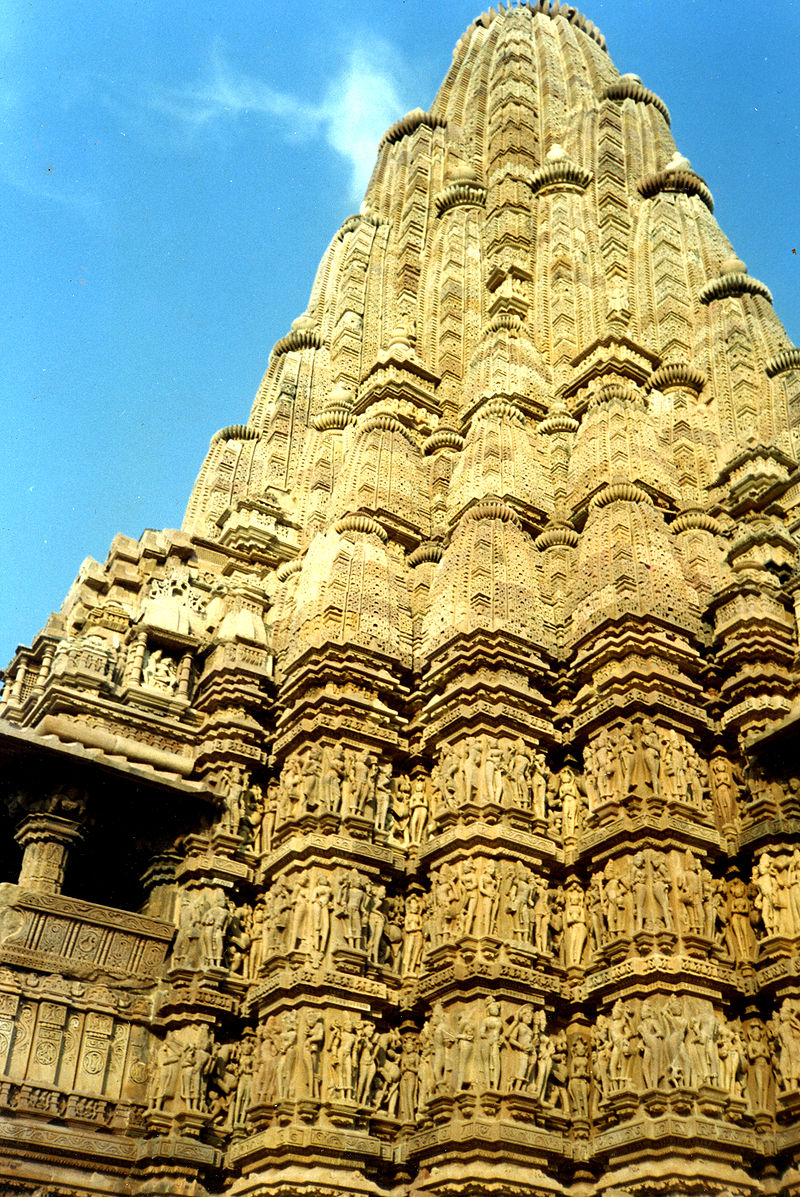

The Khajuraho Group of Monuments were constructed in the latter part of the period from the 9th to the 11thcenturies during the Chandela Empire. Different rulers in the empire built their monuments as each ruler added to the location. Historians believe eighty temples were constructed; however, only twenty-five remain. Each temple followed a similar template with a slab base, walls and appropriate windows, extravagant sculptures, and unusual conical roofs. Most of the temples were constructed with sandstone brick on a granite base. The stones were held together with mortise and tenon joints and depended on gravity to keep everything in place. They did not use mortar to hold the bricks together. The geographic region had an outstanding sandstone quality, allowing artists to sculpt fine details into the stone. Each temple had ornamented walls, columns, ceilings, and sculptures of people and animals. The temples were standardized inside also, with a porch at the Entrance, a hallway lined with pillars, and a small gathering chamber terminating in the garha-griha (the room for an image). A passageway for walking was also standard. Water was considered sacred for drinking and bathing, and lakes were incorporated into the area in specific places.

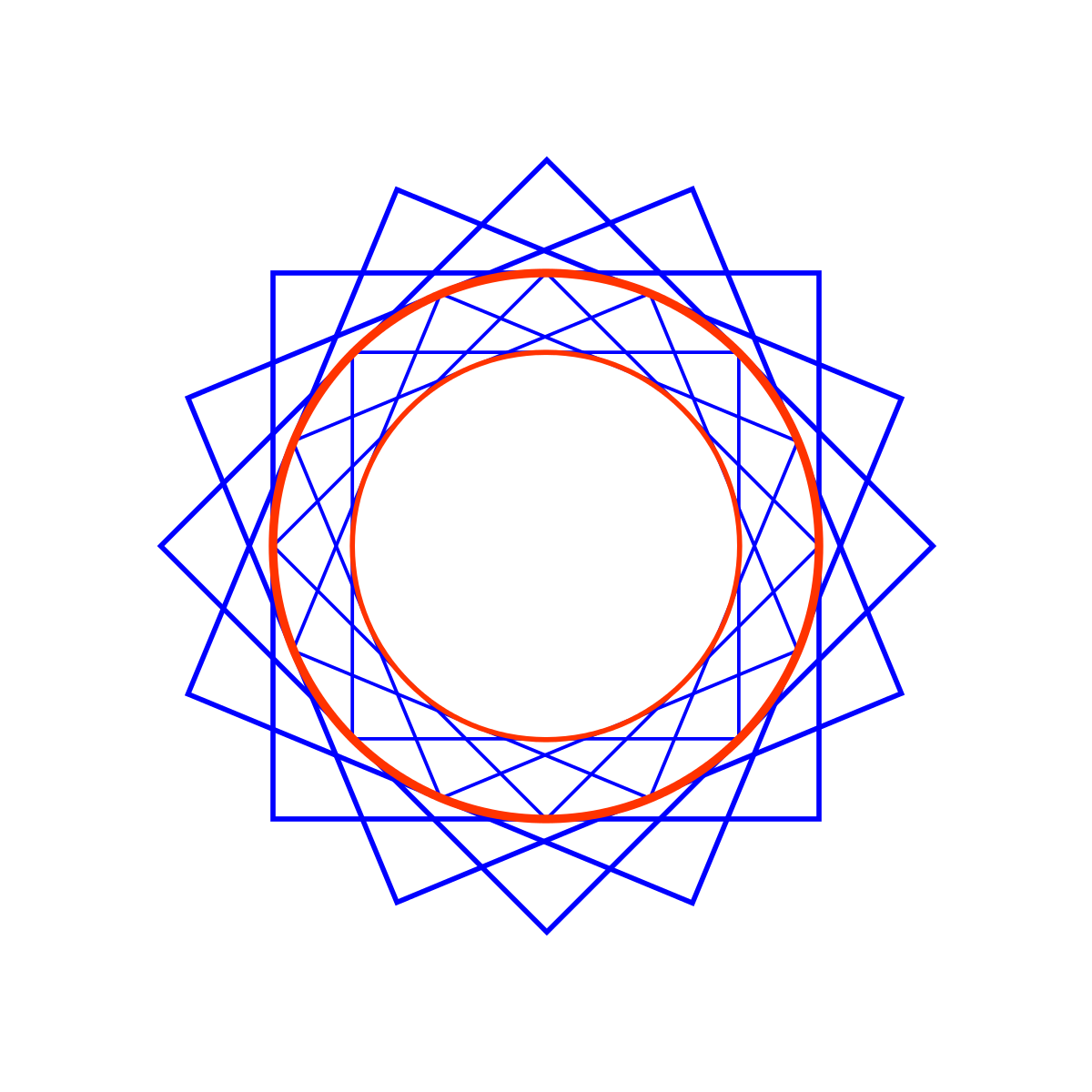

The design principle for the Hindu temples was the same, and they used circles and squares to build the vertical spires. The ratios were taken from the concept of a perfect circle and a perfect square fitted inside each other (7.2.17). Sanskrit writings identify the concepts as Vastu sastras (the science of dwelling). The design was "a kind of rotating geometry that had appeared in middle India by the seventh century and was realized with great subtlety…in the mid-eighth."[2] Under the spire (7.2.18) on the inside, the structure was constructed with squares and circles, demonstrating the symmetrical layout. A view of four temples and their spires (7.2.19) shows how the concentric shapes spiral, and the roof is built upwards in a perfectly proportioned form of harmonic ratios, demonstrating their balance, symmetry, and form.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=923&height=692)

Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (7.2.20) is the complex's biggest, most elaborate, and best-preserved temple. The temple is dedicated to Shiva to celebrate a victory. As the tallest temple at thirty-one meters high, the temple sits high up on the plinth made from granite with steep steps. The sandstone blocks are stacked in a rotating form without mortar. The temple has multiple roofs, with one section of eighty-four small towers (7.2.21) reaching upwards. The temple's interior has heavily carved walls and columns with ornate figures representing life's activities. The scene may represent dancers (7.2.22), a battle scene, people working with animals, mythical presentations, and even erotic figures (7.2.23) as part of everyday life. Some historians believe over 870 sculptures or scenes are found in the Kandarya Mahadeva Temple.

Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\): Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (China Crisis, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\): Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (China Crisis, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Dedicated to Shiva, the Vishvanatha Temple (7.2.24) is another immense temple placed high on a platform. Stairs from the base to the porch have sculptures of lions and elephants, seeming to watch the faithful climb the stairs. The highest peak of the temple is directly over the shrine at the end of the passageway. Visitors stand in the light from the doorway before going along the hall into the darkened shrine, simulating the journey from the outside world to the spiritual. Like the others, the temple was made from sandstone in the post and lintel system. Lintels were used as support for the doorways. On the exterior (7.2.25) of the building are bands of carvings and sculptures of citizens, deities, animals, plants, or mythical creatures, all based on the activities people do in their lives.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=933&height=700)

Mahavira founded Jainism in the 6th century. As a contemporary of Buddha, he opposed the caste system, as did Buddha. He also opposed the Hindu beliefs and the Brahmins supporting the caste system. Non-violence was a basic foundation of the religion. Built between 950 and 970, the Parshvanatha Temple (7.2.26) is the central Jain temple. Like the others, the temple has stairs leading to the entrance porch, which opens into a small reception hall, followed by the largest hall, before reaching the shrine at the rear of the temple. The lintel, sides, and Entrance to one of the shrines (7.2.27) are extensively carved with people and elegant designs. On the outer walls (7.2.28), multiple bands of the temple are filled with elaborately carved images encircling the entire temple. The relief images on the outside depict ordinary people, Hindu gods, and celestial beings. An example of the sculpture is the image of a common woman (7.2.29) carefully applying her eye makeup, an ordinary event before going out.

_(8638423582).jpg?revision=1)

_(8638393390).jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=947&height=707)

_(8637289891).jpg?revision=1)

Built in the medieval century by the Chandela Dynasty, the UNESCO site of ‘Khajuraho Group of Monuments’ is famous for its Nagara-Style architecture and graceful sculptures of nayikas and deities. Know more about the rich past of these well-preserved ancient temples with this video!

Nalanda University

Nalanda University was considered the world's first residential university and an international institution initially established when the Gupta Empire constructed the first monastery. Scholars taught different philosophies, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, grammar, and even alchemy, as known at the time. Nalanda was also a center for Buddhist scholarship. The Gupta rulers at the time were Hindu; however, they supported the growing Buddhist intellectual pursuits. The university was significantly expanded during the Pala Dynasty and continued expansion until the 1190s when invaders destroyed it.

By the 10th century, over 10,000 students had come from India, Japan, China, Korea, and other Asian locations. A student needed to be fluent in Sanskrit, the language used in education, and admission was by oral exams. Beliefs or nationality were not barriers; however, only 30% of the Indian applicants and 20% of the foreign applicants passed the rigorous exam. Most of the education was based on Buddhist beliefs, Hindu philosophy, science, literature, arts, and medicine.[3] The university lasted almost eight hundred years from its construction in 427 CE. Nalanda predates the earliest European university by 500 years. Teachers and scholars came from across Asia, and the university is believed to have 2,000 teachers and 10,000 students.[4] Lecture halls held over three hundred students (7.2.30).

The university was constructed on thirty acres, including viharas for student living facilities and education, multiple temples, stupas, and unique meditation sites. The university also included three libraries. International students visited the library to study authenticated copies of Buddhism's sacred books. One visiting scholar, I-tsing, reportedly stayed at Nalanda for ten years to copy four hundred Sanskrit texts.[5]

"The library contained nine million handwritten palm-leaf manuscripts and was the richest repository of Buddhist wisdom in the world, and one of its three library buildings was described by Tibetan Buddhist scholar Taranatha as a nine-story building "soaring into the clouds." Only a handful of those palm-leaf volumes and painted wooden folios survived the fire – carried away by fleeing monks."[6] Unfortunately, the university was destroyed by invading Turko-Afghan armies led by Basktiyar Khilji, whose mission was to extinguish all Buddhist knowledge.

The marauders set fire to the buildings in the 1190s and burned all the contents of the library and the rest of the school. The fire was so big and covered so much territory it supposedly took three months to burn the entire campus. Fortunately, information and books were recorded by scholars from other countries who preserved much of the valuable knowledge. Tibet's spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, said, "… the source of all the [Buddhist] knowledge we have has come from Nalanda."[7] Education in great universities shifted after the destruction of Nalanda and moved to Western countries. "Only Al Azhar in Cairo (972 CE), Bologna in Italy (1088 CE), and Oxford in the United Kingdom (1167 CE) had been founded before the destruction of Nalanda."[8]

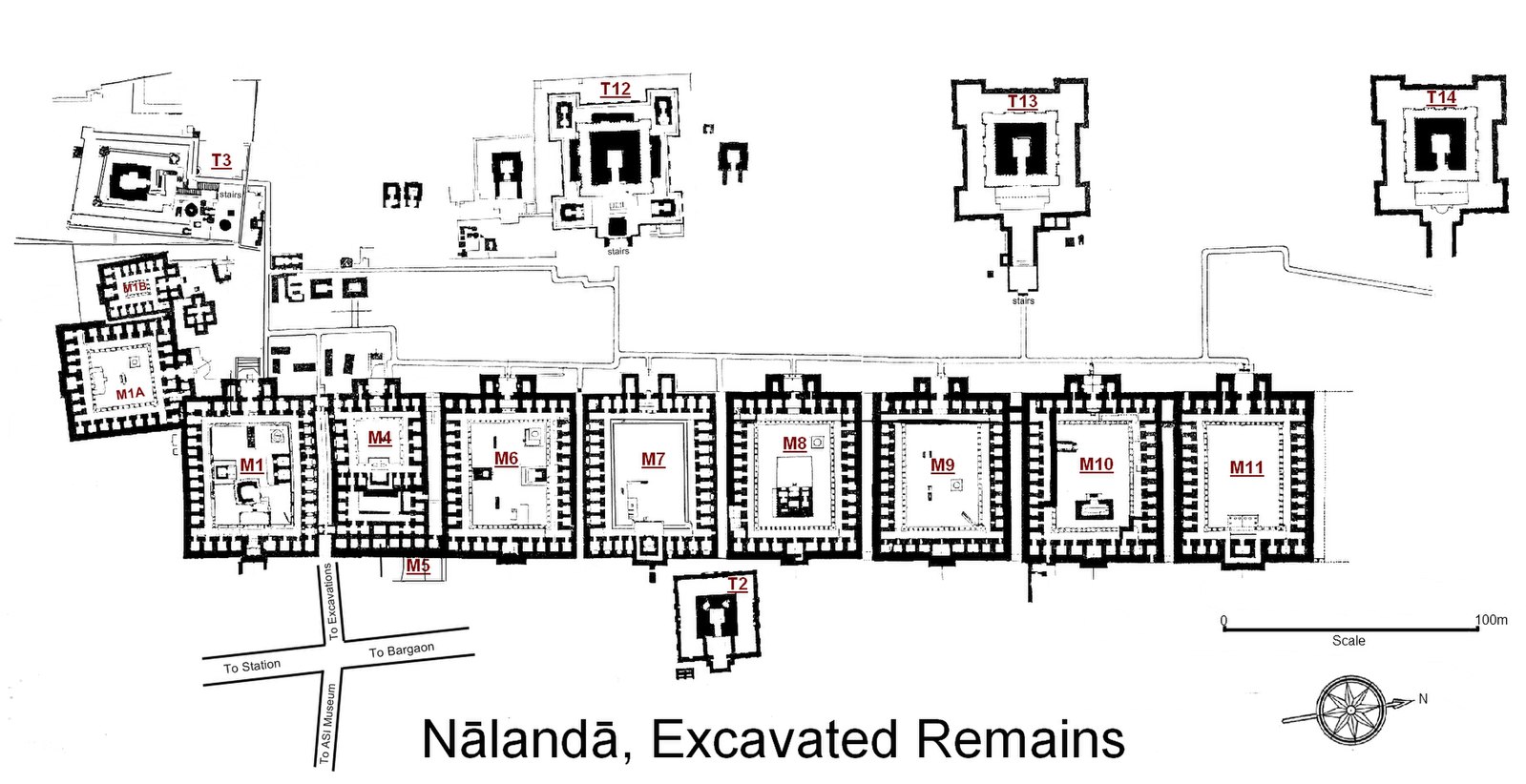

The university was constructed with red bricks and laid out on a grid, and the map (7.2.31) depicts the layout of the part of the university. One monastery (7.2.32) where the monks lived had a sunken courtyard surrounded by the monks' cells. In one corner of the courtyard was a well to supply water and the stepped platform in the center. The courtyard was used for student gatherings, meditation, and discussions. Heat was piped into the monks' rooms, and hot water was available. One of the monks' centers is listed on the map as M4.

The temple buildings were separate and constructed individually. The Stupa of Sariputta (7.2.33) or T3 on the map was believed to contain the relics of Sariputta, who was one of the prominent disciples of Buddha. The temple was originally a small structure with multiple additions, ending with seven levels and intricate stucco images of different figures. Around the temple are various stupas with inscribed bricks detailing sacred Buddhist texts. Continuing excavations have found six temples and eleven monasteries. The entire building site was constructed from decorative red brick.

%252C_Nalanda_14.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=965&height=644)

Established more than 500 years before Oxford University, at its peak Nalanda hosted over 10,000 students from around the globe. It is considered by historians to be one of the great centres of learning of the ancient world. The university was destroyed towards the end of the 12th Century AD. Its legendary library burned to the ground and much of its ancient knowledge was lost. Now, 800 years later, the university is being revived for the modern age.

Vikramshila University

Vikramshila University was constructed during the 8th century Pala empire when the king expanded Nalanda University and built the new university. As a supporter of Buddhism, the king wanted another university as a center of learning and wanted this university to be a focus of Tantric Buddhism. India had a network of monasteries that communicated with each other as scholars moved from place to place to study. Thousands of students at the university studied logic, philosophy, and theology taught by educators from across Asia. The university was destroyed by the same invaders in the 1190s who destroyed Nalanda and the other universities.

Vikramshila University covers 100 acres, although archaeologists still work to evacuate parts of the site. The massive stupa (7.2.33) was the focal point in the center of the site. The original bricks for the stupa were not fired correctly, and today, they are difficult to carefully excavate as the bricks are so fragile and crumble easily. The stupa was terraced and stood about fifteen meters above ground. The stupa had four rooms filled with images of the Buddha. The openings to the rooms had stairs and were sited towards the four cardinal directions.

The stupa sat in the middle of the surrounding monastery, constructed in a large square holding fifty-two cells on each side to provide residences for over 200 monks. A vast area (7.2.34) across from the stupa was walled in and filled with small stupas and broad pathways. Students walked in the area, meditated, and communicated with each other. On the walls of the terraces were decorations made from terracotta plaques (7.2.35), demonstrating the high skill of terracotta artists. The plaques portrayed different deities, scenes of Buddha, and images of people engaged in hunting or social activities. The tradition of making terracotta plaques started in the early periods and continues today. The plaque was fired at a high temperature and frequently covered with sand to cool down, achieving a bright red color. If the vents to the kiln were tightly covered, the terracotta was darker or black, and the vents were slightly open for the red color.

Bronze Statues

Bronze was a common material for artists throughout India and was used for centuries. Some statues were created with a formal frontal view, others captured an image in static motion, and some views were fluid with the illusion of movements. Statuary became an everyday object, from small objects in a house to oversized sculptures for religious rituals. Most sculptures and small statues were made as icons for Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism and used in religious devotions. Production was widespread throughout the regions from 600-1200 CE, with the styles varying from region to region. Universities like Nalanda had a school for bronze-casting. Those statues made during the Chola period are considered some of the best bronze sculptures made. Artists usually used the lost-wax method to make the statues.

The Hindu god Shiva (7.2.36) is depicted as the divine cosmic dance in the form known as Nataraja. His pose and dance moves are found in Hindu writings and are typical sculptural images in Indian culture. Shiva is balanced on his right leg on top of the demon of ignorance. His left leg is poised in a raised position to kick away the veil of illusion. He has four arms; the upper right holds a musical instrument, the upper left carries a flame, and the main left hand is held in the dola hasta position. His hair flies on each side to touch the jvala mala or garland of flames surrounding the figure.[9]

[1] Bose, M. ed., (2004). The Ramayana Revisited, Oxford University Press, p. 341.

[2] Meister, M. W., Mountain Temples and Temple-Mountains: Masrur, The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 65/1, Mar. 2006. P 39.

[3] Weeraratne, D. A., The Six Buddhist Universities of Ancient India, Buddha Sasana.

[5] Anis Khurshid (1972) Growth of libraries in India, International Library Review, 4:1, 21-65, DOI: 10.1016/0020-7837(72)90048-9

[6] Nalanda: The university that changed the world

[7] Mishra, A. Revived Nalanda University Will Balance Local and Global Research, University World News, February 16, 2013, No. 259.