11.5: John Newton - “Amazing Grace”

- Page ID

- 92075

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

So far, we have examined compositions for use in Christian worship that are fixed in terms of their musical details. Two recordings of Sleepers, Wake, for example, might differ slightly in terms of tempo or timbre, but they will sound essentially the same. They will certainly contain all of the same pitches and rhythms, and will be similar in length. These are all characteristics of the classical tradition, in which the composer exercises a great deal of control over the musical work.

Next, however, we will examine an example of Christian worship music that has changed dramatically as it has been adopted and adapted by different religious communities. In fact, the only element of “Amazing Grace” to remain consistent throughout its lifetime has been the words, although all of the versions under consideration here also use the same melody—that which will be familiar to those who know the hymn. This stylistic flexibility is typical of music in the vernacular tradition, which permits the reinterpretation and transformation of musical compositions by individual performers.

No-one has ever performed Sleepers, Wake without being aware that it was composed by J.S. Bach, but people sing “Amazing Grace” every day without knowing who penned the words or music. Indeed, those are not easy questions to answer—the text, although initially written by John Newton (1725-1807), was later expanded by an anonymous author, while people still debate the identity of the tune’s composer. People who know this hymn are more likely to identify it with one of its great interpreters, such as Aretha Franklin, whose version we will encounter below.

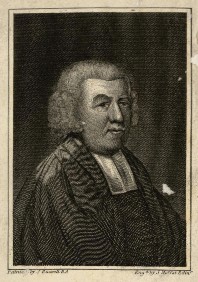

Newton’s Life

The story of “Amazing Grace” begins with John Newton, who wrote six verses— some familiar from modern usage, some not—in 1772. Newton was a clergyman in the Church of England. He served as curate in the village of Olney, where his parishioners were largely impoverished and uneducated. Newton gained a reputation for impassioned preaching that spoke to the personal moral struggles of his congregants. Unlike other preachers, Newton willingly shared sins from his own past—and those were certainly in no short supply.

Newton took to the sea as a ship’s apprentice at the age of eleven, but was pressed into service with the Royal Navy after refusing to obey his captain’s orders. After deserting the Navy to visit a young lady, Polly Catlett, he was traded to a slave ship, where he developed a reputation for writing obscene songs and using language that shocked even sailors. Newton had renounced his Christian faith early in his seagoing career, but in 1748 a near-death experience aboard the ship Greyhound inspired him to reconsider his beliefs. He was further encouraged by his love for Polly, whom he married in 1750. All the same, it was many years (and another brush with death) before Newton reformed in any meaningful way, and he continued to work in the slave trade well into the 1750s. Newton began studying theology in 1756 and was finally successful in securing ordination and his position at Olney in 1764.

At Olney, Newton began writing hymns for his congregation to sing together at weekly prayer meetings. Newton’s hymns used simple language that was easily intelligible to his parishioners, and many of his texts were written in the first person. They focused on the confession of sins and the joys of salvation. Although the quality of his verse was criticized by some, Newton’s hymns became quite popular. They first appeared in print as part of the 1779 collection Olney Hymns, which included “Amazing Grace”:

Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound) That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found, Was blind, but now I see.

‘Twas grace that taught my heart to fear, And grace my fears reliev’d;

How precious did that grace appear The hour I first believ’d!

Thro’ many dangers, toils, and snares, I have already come;

‘Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far, And grace will lead me home.

The Lord has promis’d good to me, His word my hope secures;

He will my shield and portion be As long as life endures.

Yes, when this flesh and heart shall fail, And mortal life shall cease;

I shall possess, within the veil, A life of joy and peace.

The earth shall soon dissolve like snow, The sun forbear to shine;

But God, who call’d me here below, Will be forever mine.

Although it is known that Newton’s congregation used his “Amazing Grace” text beginning in 1773, we have no idea what tune or tunes the text was sung to. It certainly was not the tune we know today. Newton was not a composer, but he always intended for his devotional poems to be sung. Like other hymn text authors, he crafted his verses using specific patterns of syllables and rhymes so that they could be sung to preexisting melodies. This system of interchangeable texts and tunes meant that any hymn text could be sung to a variety of tunes and any tune could be supplied with a variety of texts. Only over time have specific texts and tunes in the hymn tradition come to be paired off, such that churchgoers expect a text—“Amazing Grace,” for example—always to be sung to the same melody.

“Amazing Grace”5 in the Sacred Harp Tradition

|

“Amazing Grace” 5. Performance: Texas Sacred Harp Singers, Southwest Sacred Harp Singing Convention (2011) |

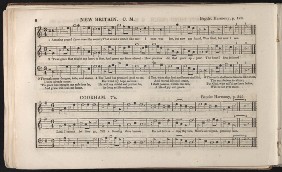

The pairing of “Amazing Grace” with its tune took place in 1835, when William Walker published a version in his hymnal Southern Harmony. The name of the tune was “New Britain” and it had already been in circulation for some time, although in the company of different texts. The authorship of “New Britain” is still contested. It was based in turn on two older melodies that first appeared in the 1829 hymnal Columbian Harmony. These tunes are unattributed, which indicates that they might be the work of hymnal compilers Charles H. Spilman and Benjamin Shaw. It is equally likely, however, that the tunes derive from folk tradition and might trace their origin to the British Isles. The “New Britain” tune also appears in an 1828 manuscript compiled by hymn composer Lucius Chapin, who has been proposed as yet another potential author. It is unlikely that a composer will ever be identified—if, indeed, “New Britain” was even the product of a single composer, which we have reason to doubt.

By the time William Walker published his version in 1835, the “Amazing Grace” text had already become very popular in the United States. It was widely used during the Second Great Awakening, which saw the staging of revivals across the country. These revivals featured charismatic preachers, who swayed crowds using emotionally charged speech punctuated with song. The verses of “Amazing Grace”—which embodied the personal, confessional approach to conversion favored by these preachers—were paired with simple refrains and sung to familiar tunes without the aid of hymnals.

Walker was not personally associated with the Second Great Awakening, but he made his living as a hymn publisher and singing teacher, and was therefore aware of trends in the world of Protestant worship music. Walker belonged to the American hymn tradition known as shape-note singing, which encompasses a unique form of notation, an approach to music education, and a compositional style.

The notation used in the shape-note tradition was first developed in late-18th century England for the purpose of simplifying the task of reading music. As its name suggests, shaped notation employs various shapes—each paired with a syllable—to represent the different pitches. In its original form, the system used only four shapes, even though a scale contains seven distinct pitches. The shapes were repeated in a way that maintained consistent patterns of intervals between shapes. If a singer could learn the intervallic distance between two shapes, they could easily sing music at sight. The syllables provide an additional tool for singers and also make it easy to teach the system. (The use of syllables to learn melodies actually dates back to ca. 1026, when the Italian monk Guido of Arezzo proposed a system that used six syllables—including the four later adapted by shape-note enthusiasts.)

Shaped notation was adopted in the United States as part of a movement to improve church music. During the second half of the 18th century, music lovers in New England began to lament the sorry state of American congregational singing. Churchgoers were largely illiterate, and they did not have access to hymnals or instruments. The most common method of hymn singing, known as lining out, required a songleader to call out a musical phrase, which the congregants would then repeat in unison. Activists wanted to restore four-part harmony to the worship service, but this would require music literacy and access to printed notation.

To fulfill both of these needs, entrepreneurs began to publish hymn books and offer singing schools. A singing master would travel around a region, spending two weeks at a time teaching anyone who was interested how to read using the shape- note system. Singing schools were usually hosted by a church, and classes would meet daily. These schools not only paved the way to better church music, but also provided much-needed entertainment to farming communities during the winter months and facilitated interactions between young men and women, who had few opportunities to encounter one another unchaperoned. The students would not only pay tuition to the singing master but would purchase hymn books—another important source of income.

The hymns composed in the American shape-note tradition were unique. Most of the composers—William Billings (1746-1800) and Daniel Read (1757-1836) were the most famous to emerge from the First New England School—were self- taught, and they gleefully rejected the conventions of European harmony and part writing. Their hymns contain unusual and harsh sounds (the result of breaking voice-leading rules), uneven phrases, and incomplete chordal harmonies (open fifths in place of triads). The shape-note composers also adhered to the ancient practice of putting the melody in the tenor part instead of the soprano—an approach, dating back to medieval church polyphony, that had already disappeared from European choral music.

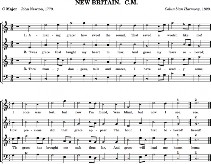

The singing school movement was launched in New England, but by the early 19th century had come to be regarded as outdated. The North, after all, aspired to a cosmopolitan identity and was embarrassed by the primitive efforts of its shape- note composers. The movement, however, found a new home in the South, where rural singing masters flourished up until the Civil War. It was there that the most influential hymn books were published. William Walker’s Southern Harmony was among these, but without question the most important shape-note hymnal was The Sacred Harp (1844), published in Georgia by Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha J. King. Unlike other such hymnals, The Sacred Harp has remained popular into the present day, and enthusiasts around the world regularly gather to sing from its pages. As such, the tradition of shape-note singing is today most commonly referred to as Sacred Harp singing.

Participants in modern Sacred Harp sings adhere to a number of practices that originated in the singing school movement. To begin with, their purpose is not worship but music marking. Many Sacred Harp enthusiasts also profess Christian beliefs, and sings often begin and end with prayer, but Sacred Harp thrives because participants are committed to the music.

At a typical sing, participants sit in a formation known as a “hollow square,” with singers—seated according to vocal part—facing a central open space. Although the vocal parts are gendered in typical choirs, this is not the case in Sacred Harp: Women will frequently sing the tenor part up an octave, while men will sing the soprano part down an octave. There is no conductor. Instead, participants will take turns selecting hymns, which each will direct from the central position. The person who chooses the hymn will specify which verses are to be sung, and someone will provide the starting pitches for each part. Then the group will sing through the hymn once on the syllables before turning to the text.

The vocal style associated with Sacred Harp singing is also unusual. Participants do not tend to approach their task with nuance. Instead, each sings as loudly and exuberantly as they can, often accenting the rhythms with physical movement (something that is expressly prohibited in choral singing). The tempos are steady. Finally, there is never instrumental accompaniment.

“Amazing Grace,” paired with the tune “New Britain,” appears in both Southern Harmony and The Sacred Harp. The Southern Harmony version contains only three voice parts (soprano, tenor, and bass), but editions of The Sacred Harp eventually added an alto part. (Experienced singers might notice that the soprano part is very high. This notation, however, is not meant to be taken literally, and most groups will sing the hymn in a lower key.) The familiar melody is in the tenor in both versions, while the other parts provide harmony above and below. As a result, a performance of this version of the hymn strikes most listeners as familiar, but somehow strange.

Our rendition of “Amazing Grace” was recorded at the Southwest Sacred Harp Singing Convention in McMahan, TX, in 2011. After an initial pass using the syllables, the participants sing the first four verses of Newton’s text.

“Amazing Grace” in the Southern Gospel Tradition6

Soon after the 1844 publication of The Sacred Harp, a rift emerged in the Southern hymn publishing community. In 1846, Jesse Aiken published The Christian Minstrel, which introduced a new shape-note system using seven shapes. This development seemed natural enough. As one advocate for the new system put it, “Would any parent having seven children, ever think of calling them by four names?” Aiken’s hymnal provoked a virulent debate. While some publishers refused to adopt the new system, others were won over. William Walker himself switched to seven-shape notation with his 1866 hymnal Christian Harmony. Eventually, the seven-shape system emerged victorious.

|

6. “Amazing Grace”Performance: The Inspirations (1976) |

Other changes came upon the hymn publishing industry as well. By the late 19th century, the stark harmonies of The Sacred Harp had largely been eschewed in favor of more pleasing harmonies derived from popular music. Hymn composers moved away from the minor mode—which dominates the pages of The Sacred Harp—and began to write in a more cheerful vein. Composers also abandoned the archaic practice of placing the melody in the tenor voice, instead putting it in the soprano and supporting it with accompaniment in the lower parts. Finally, piano accompaniment was introduced in the early 20th century as churches gained access to instruments.

All of these characteristics describe the Southern gospel tradition, which continues to flourish. Southern gospel music is driven by hymn composers and publishers, who supply a steady diet of new hymns. These are sung at conventions, which attract vast numbers of singers eager to test their reading ability on unfamiliar music. At the same time, Southern gospel devotees enjoy singing old favorites, such as “Amazing Grace.” Although Southern gospel music does not belong to a single Christian denomination, it is closely associated with evangelical branches such as the Southern Baptist Convention.

In the early 20th century, Southern gospel publishers began sponsoring professional quartets to sing their music. These quartets—which were at first all- male—toured the singing conventions, where they would perform the latest hymns from a particular publisher. They also participated in revivals, gave concerts, sang on the radio, and released commercial recordings. It might be argued that Southern gospel transformed from a participatory musical tradition to a performative one, for today many people think of Southern gospel primarily as a commercial music genre. At the same time, collective singing of Southern gospel music continues to take place in churches and at singing conventions.

Our example was recorded by the Inspirations in 1976. The Inspirations follow solidly in the model established in the early 20th century by publishers’ quartets. The group was formed in 1964 when Martin Cook, a high school chemistry teacher in Bryson City, NC, began singing gospel music with four of his students. A couple years later they founded a gospel music festival, Singing in the Smokies, and by 1969 the Inspirations were a full-time professional group. A string of number-one gospel hits in the early 1970s cemented their reputation.

The Inspirations’ recording of “Amazing Grace” was created during a live performance in Warner Robbins, GA. This is important, both because the sounds of the audience contribute to the effectiveness of the recording and because the release of live albums is a meaningful practice in the gospel tradition. After all, this music is intended to have a profound and personal impact on the listener. The Inspirations describe themselves as “an enthusiastic, sincere, clean-cut group of fundamental conservative Christian gentlemen with a desire and an objective to witness to a needful and sinful world through the medium of Gospel Music.” They make music not to entertain an audience but to save it.

The first verse is sung by lead tenor Archie Watkins. As is typical of the genre, he sings the melody in the highest part of his range. This means that the top notes sound almost like cries. We can hear that he is straining to reach them—an effort that is emotionally compelling and communicates the sincerity of the message. This type of singing has roots in the tradition of secular Appalachian music- making, and can be heard in banjo songs and bluegrass. Watkins does not sing with a steady pulse, as we heard in the Sacred Harp rendition, but takes his time to express each individual word.

For the second verse, the ensemble enters to supply a wordless harmony, switching to text only for the final two words. The third verse is sung on text by the entire ensemble, although Watkins high melody still stands out from the texture. We also hear the low bass singing of Mike Holcomb—another characteristic feature of the Southern gospel music.

The third verse sung by the Inspirations, however, is not the third verse of Newton’s text:

When we’ve been there ten thousand years, Bright shining as the sun,

We’ve no less days to sing God’s praise, Than when we first begun.

In fact, this verse wasn’t written by Newton at all. It was first published in the 1790 Virginian hymnal A Collection of Sacred Ballads, in which it was incorporated into the much older hymn “Jerusalem, My Happy Home.” (In The Sacred Harp, the verse appears as part of “Jerusalem, My Happy Home” and “Ninety-Fifth Psalm,” but is not included in “Amazing Grace.”) The first person to associate this verse with “Amazing Grace” was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In Stowe’s narrative, Uncle Tom sings three verses of “Amazing Grace”—two of Newton’s verses and the new one—to mark his moment of greatest spiritual need.

It is typical for favorite verses to appear in more than one hymn. This is the result of oral tradition. A certain verse—memorable for its imagery or message— sticks in a singer’s head. They then add the verse to another hymn, one that has a tune with the same pattern of strong and weak beats. It is believed that Stowe was drawing from African American oral tradition in particular when she included this verse in “Amazing Grace.” However, it was not included in a hymnal until the 1910 Coronation Hymns.

“Amazing Grace” in the Black Gospel Tradition7

Black gospel is not unrelated to Southern gospel. The two traditions share a great deal in common and have always influenced one another. In the period during which these traditions developed, however, American society was highly segregated—by Jim Crow laws in the South and by less visible means in the North. It is unsurprising, therefore, that a unique tradition of music, based in part on African American musical tradition, should have arisen among black worshippers.

|

7. “Amazing Grace” Performance: Aretha Franklin (1972) |

The style of music making that would come to be known as black gospel emerged first in the Holiness churches of the early 20th century. These congregations traced their roots to the revival meetings of the Second Great Awakening, in which many African Americans had participated. They favored a highly expressive and emotional form of worship, in which individual congregants might be moved to speak or sing.

During the 1920s, musicians in Holiness churches began to incorporate popular influences into worship. These included styles of piano playing derived from ragtime, percussion and brass instruments associated with jazz, and blues- inspired vocals. Although some churchgoers were skeptical about the inclusion of secular sounds in worship, the music gained popularity with the success of early recordings by artists like Arizona Dranes, a blind pianist and singer who belonged to the Church of God in Christ.

In the 1930s, male quartets—much like those in the Southern gospel tradition— and choirs came to the fore as black gospel gained followers. Although the style borrowed from popular music, it maintained strict separation from the commercial world, and gospel singers who made secular recordings were often shunned by the church community. At the same time, black gospel exercised enormous influence on the development of popular music. This influence is especially evident in the singing styles that emerged in rhythm ‘n’ blues and, later, soul. It is no wonder that many successful gospel artists were attracted by the possibility of mainstream popular success.

Aretha Franklin (1942-2018) was among the most prominent of these crossover singers, although anxieties about secular music had largely subsided by the time her career took off. Franklin was the daughter of a Baptist minister, C.L. Franklin, and she first sang in the church. Her father was something of a celebrity, and Franklin got to know many of the great gospel singers while she was still a child. At the age of 12, she began accompanying her father on preaching tours, for which she would provide stirring music. At 18, however, she decided to leave gospel behind for a career in popular music. With her father’s support, she moved to New York City and signed with Columbia Records.

Franklin did not flourish at Columbia, and it was not until she moved to Atlantic Records in 1967 that her career took off. Her version of “Respect,” which topped the R&B and pop charts that year, was just the first in a chain of hit singles and albums. At the height of her success, however, Franklin returned to her roots and recorded a gospel album, the 1972 Amazing Grace. It was to be the top-selling album of her entire career.

Amazing Grace was recorded live over the course of two evening concerts at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles. Franklin was backed up by the Southern California Community Choir and the prominent gospel singer Reverend James Cleveland. The title track, “Amazing Grace,” is the longest on the double album, clocking in at nearly eleven minutes. (Our version, taken from the master recording, is over sixteen minutes long.) The selection was featured near the end of the first evening’s concert, and was without doubt the high point of the show.

As with the Inspirations’ recording discussed above, the fact that Franklin’s “Amazing Grace” was recorded live is important. The sounds of the audience help us to visualize the church setting and remind us that this is worship music. We don’t just hear the song—we also hear people being moved and transformed by the song. The shouts and applause of the listeners are integral to the performance. The audience noise also helps us to understand the motivations of the singer. Aretha is not just performing a song: She is expressing her deeply held beliefs in an intensely personal way. Finally, we can hear how the audience shapes the performance. As they respond to Franklin’s singing, they also inspire her to new heights of expression.

Franklin’s singing style is emblematic of the black gospel tradition. She in fact only sings two verses of the hymn: the first and third. However, she weaves them into an epic drama, full of twists and turns. Every vowel of the text is drawn out in a long melisma containing many notes, and there is never a sense of pulse. Although the first verse is elongated and intense, we soon find out that Franklin was only getting started. The emotional energy builds with the third verse, in which Franklin brightens her timbre as she moves to the top of her range. She also adds a great deal of new text, which gives the impression of having been improvised on the spot. With these added words, she personalizes the message and seems to confess her own sins. She speaks directly to the people in the room through music. In the final line of the verse, however, Franklin abandons the texts and insteads hums an additional iteration of the melody. By doing so, she draws down the emotional energy for the purpose of producing an even more dramatic final conclusion. Upon returning to the text of verse three, Franklin inaugurates a series of call and response passages between herself and the choir/audience. Again, the verse fails to conclude, and the choir enters with the third-line text. It seems almost as if they are trying to provide Franklin with the strength to finish the hymn. When Franklin returns with the first line of the verse, she builds her singing into shouts and cries before finally arriving “home.”

These three renditions of “Amazing Grace” are remarkably different. Variations in performing forces—choir vs male quartet vs solo female vocalist with piano accompaniment—do not even begin to explain the variations in aesthetic and emotional impact. Instead, we have to examine the vocal styles that are characteristic of each performing tradition—styles that in turn make sense only in the context of worship practices that are each unique to a time and place. In the end, we see how a hymn written centuries ago by a reformed slave trader can embody and express the spiritual values of diverse individuals and sects.