11.4: Johann Sebastian Bach - Fugue in G minor and Sleepers, Wake

- Page ID

- 92074

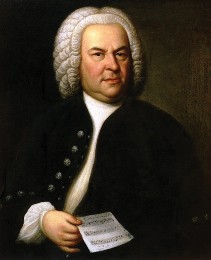

About 150 years later, another composer of church music was also guided by the needs and preferences of his faith community. The church music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685- 1750) is quite different from that of Palestrina, however, both because musical tastes had changed in the intervening years and because Bach worked not for the Catholic but for the Lutheran Church. We will take a look at two of his most famous creations: a piece of music for the organ and a composition for choir and orchestra.

Bach’s Legacy

Today, the music of J.S. Bach is performed more frequently than that of almost any other composer from the European tradition. Ensembles all over the world are dedicated to his music, while countless books have detailed his life and works. He is esteemed by many as the greatest composer of all time (although, as will be discussed in the final chapter of this book, it is nearly impossible to define “greatness” in music).

All of this would have very much surprised the composer himself. During his lifetime, Bach was not particularly famous or respected, and he struggled constantly with difficult working conditions and low pay. He was better known as an organist than as a composer: While Bach was respected as a virtuoso performer, his compositions were considered old-fashioned and stuffy. Only a handful of his works—mostly for keyboard—were published before his death, and he had no reason to expect future generations to take any interest in his music.

Bach’s fortunes shifted in the early 19th century, when German musicians began to revive and popularize his music. The most significant such event took place in 1829 when the composer Felix Mendelssohn staged a performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in Berlin. Like Sleepers, Wake (German: Wachet auf), which we will examine, the St. Matthew Passion was a work for choir and orchestra intended for use in a Lutheran church service. Bach never imagined that any of his church music would be performed in concert halls or consumed as either art or entertainment. He sought only to support the work of the church. Since the time of Mendelssohn, however, Bach’s choral compositions have been a staple of the concert repertoire, and today’s listener can access thousands of recordings.

A brief examination of Bach’s life and career will serve to contextualize his work as a composer. Bach was born into a large family of German musicians that extended back for many generations. His father, grandfather, great-grandfather, uncles, and other male ancestors were all performers and in most cases composers, while his sons were all to become composers as well. From the time of his birth, therefore, there was no doubt about Bach’s future career. Musicians of his time and place generally found employment with either a court or a city, in which capacity they would produce new compositions, oversee performances, and participate in those performances as instrumentalists or singers.

Bach’s Career

Bach never lived outside the region of Thuringia, which today is located in central Germany, and he never travelled beyond the borders of the modern German nation. Following an education in Eisenach, he took a series of five professional posts. First he served as a church organist in the cities of Arnstadt (1703-1707) and Mühlhausen (1707-1708). His next position was at the ducal court in Weimar (1708-1717), where he played the organ and served as music director. After this he became music director at the court of Prince Leopold in Köthen (1717-1723). Finally, Bach took the position of music director at the St. Thomas Church in the city of Leipzig, where he remained until his death.

Famously, Bach was not the city council’s first choice for the job. They initially offered the post to a composer—Georg Philipp Telemann—whose music is only seldom performed today, but who at the time was considered to be more fashionable. Bach was in turn loathe to accept the job, which was less prestigious than the post he held in Köthen. He made the move to Leipzig, however, out of concern for his family. Bach, who was married twice, had a total of twenty children, ten of whom survived into adulthood. Leipzig had excellent schools, and he knew that his sons would have better prospects in that city. Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena, was herself a highly-skilled musician. She provided her husband with invaluable assistance, copying out parts by hand each week so that the church musicians could perform his music during the Sunday service.

In Leipzig, Bach was required to perform a variety of tasks on behalf of the municipal government. He was principally responsible for music at the St. Thomas Church, but also oversaw music at the city’s other three churches. As music director, Bach produced instrumental and vocal compositions for use in the church, hired musicians, ran rehearsals, and played the organ. He also taught music and Latin at the St. Thomas School, which was attached to the church. Finally, he was obliged to produce music for civic occasions, including commemorations of important events and celebrations of esteemed visitors.

Bach frequently complained about his immense workload and limited resources. He felt that the city did not provide adequate funds with which to hire the musicians that he needed, and he often had to limit his instrumentation due to budgetary concerns. Although today one can hear Bach’s music rendered by the best choirs and orchestras in the world, Bach himself was seldom able to arrange for high-quality performances of his music. He relied primarily on students from the St. Thomas School and from the nearby Leipzig University.

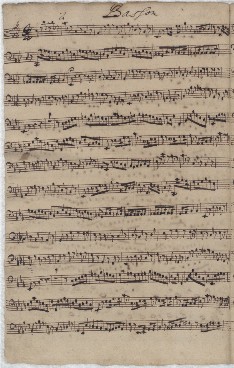

We will examine two pieces of church music from two different parts of his career. Bach’s Fugue in G minor dates from his early years as a church organist in Arnstadt. Like most of Bach’s music, it has survived only as a handwritten manuscript. The same it true of Sleepers, Wake, which was created in 1731 for use at the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig.

Fugue in G minor

Bach wrote hundreds of fugues, most of which had nothing to do with his work as a church musician. The term fugue refers to a compositional technique that can be applied across genres. Bach wrote most of his fugues for keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord, which resembles a small piano in appearance but creates sound using quite a different process: When the player depresses a key, it causes a string to be plucked with a quill or piece of hard leather. Most famously, Bach twice wrote keyboard fugues in every major and minor key. His two collections, known as The Well-Tempered Clavier Book I (1722) and Book II (1742), were intended to demonstrate a new method for tuning the harpsichord. Bach also wrote fugues for solo string instruments, orchestra, and choir. One of Bach’s final works, entitled The Art of Fugue, was left incomplete at his death but nonetheless demonstrated his ultimate mastery of the technique.

Fugal technique was widely employed in the 18th century. It is simple in principle, but very challenging to execute. Whether a fugue is written for instrumentalists or singers, we always speak of its “voices” and use the typical choral designations: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Most fugues have four voices, although Bach wrote for as few as two and as many as six.

Every fugue begins with a solo melody in one of the voices. This melody is called the subject. The composer will introduce the subject in each of the voices in turn until all have entered the texture. This section of the fugue is called the exposition. For the remainder of the fugue, sections that do not contain the subject, which are known as episodes, will alternate with statements of the subject, which constitute the development. The subject will appear in many different keys and sometimes in different forms (for example, the melody might be turned upside down) until finally it is heard one last time in the original key and the fugue concludes. A fugue might have many episodes or none at all, and there is no predetermined length or precise form.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Exposition |

The subject is heard first in the soprano voice, then alto, then tenor, then bass |

|

0’51” |

Episode |

All of the episodes consist largely of sequences |

|

0’58” |

Subject |

After a false entrance in the tenor, the subject is heard in the soprano |

|

1’11” |

Episode |

|

|

1’17” |

Subject |

Heard in the alto |

|

1’28” |

Episode |

|

|

1’36” |

Subject |

Heard in the bass |

|

1’47” |

Episode |

|

|

1’59” |

Subject |

Heard in the soprano |

|

2’10” |

Episode |

This is the most diverse and lengthy episode |

|

2’31” |

Subject |

Heard in the bass; the tempo slows before the final cadence |

Fugue

Episode(s)

Bridging material for return to Subjects

Exposition

• Subject introduced

• Subject answered (in different keys)

• Countersubjects accompany subjects

Optional: Coda (at the end)

Development

• Subject presented in different keys

• Possible transformations of the subject (inversions, etc.)

Final

Episode(s)

Bridging material for return to Subjects

• Subject and countersubject in the original key

Fugues are difficult to write because the composer must follow complex rules concerning the relationships between the voices. These rules concern the distances between simultaneous pitches, the directions in which voices move, the special treatment of notes that do not belong to chords, and the keys in which the subject must appear. Because the subject itself can never be altered, the composer must employ all of their skill to avoid breaking rules. (These rules are not arbitrary, but rather emerged over decades of practice and guide the composer in creating a fugue that sounds good.) Bach seems to have enjoyed the challenge of fugue writing, and he often created subjects that were especially difficult to work with.

Although a fugue is not necessarily an example of church music, Bach composed

organ fugues for use in Lutheran church services. We will examine a fairly simple fugue that he composed in his capacity as church organist for the city of Arnstadt. He would have played his Fugue in G minor at the beginning or end of services, but also on organ recitals that were intended not for worship but for the enjoyment of the audience. While this piece of music sets a mood that is appropriately serious for worship, its complexities also reward careful listening.

In Arnstadt, Bach played on an organ that had just been installed by the builder Johann Friederich Wender. All organs work by blowing air through pipes, which might be made out of wood or metal, be of various shapes, or contain reeds. These variations allow organs to produce many different sounds. Most organs have multiple keyboards, each of which can be linked to one or more sets of pipes. In this way, the performer can quickly change from one sound quality to another by moving between keyboards. Sets of pipes are activated or deactivated by adjusting wooden rods known as stops. Organs also have an additional keyboard, termed the pedalboard, that is operated using the feet. The pedalboard is typically linked to pipes that sound in the lowest register.

Despite its complexity, the organ is actually one of the oldest instruments found in Europe. Organs were first developed in ancient Greece over two thousand years ago. Although early organs were small and portable instruments, they began to grow in the 14th century when the first permanent organ was installed in a church. By the 19th century organs had become enormous instruments capable of producing a great range of volumes and timbres. Bach’s organ in Arnstadt is still played today. Like other Baroque organs, it is fairly small, although still capable of producing a wide variety of sounds. It has two keyboards and a pedalboard, which together give the player access to twenty-one sets of pipes. Baroque organs are not capable of gradual changes in dynamic. The performer can suddenly alternate between loud and soft by changing keyboards, but all notes played using a given set of pipes are the same volume. Fugues, therefore, are most often performed without any dynamic changes.

Bach’s Fugue in G minor (often called the “Little” Fugue in G minor, to distinguish it from others in the same key) has a five-measure subject. The subject begins with long note values, but gradually incorporates shorter and shorter note values as it proceeds. This creates an impression of increased activity, even though the tempo does not accelerate. The fugue has four voices, which enter from highest to lowest in the order soprano-alto-tenor-bass. The texture quickly becomes dense, and—after the opening measures—at least one voice is moving rapidly at all times. Although the fugue is short, therefore, one needs to listen to it several time to hear everything that is going on. It can be challenging to pick out the subject, even once it has become familiar.

Bach was noted for the density and complexity of his music. Indeed, that was the characteristic that earned him scorn in his own time—just as it earned him respect a century after his death. He also preferred to establish and then maintain a single mood with each piece of music. As such, there is little expressive variation within the Fugue in G minor. Once the engine starts, it runs steadily and unerringly until the final cadence.

Sleepers, Wake

During the early years of his employment in Leipzig, J.S. Bach dedicated most of his energy to the creation of Lutheran church cantatas. This was a big job because the churches there required a new cantata every week. The Lutheran liturgical calendar is organized into a year-long cycle of Biblical readings, and the cantata corresponded with the topic of the readings and the sermon. For this reason, Bach needed to produce an appropriate cantata for every Sunday morning Mass and for special services, making for a total of sixty cantatas a year.

After his first year on the job, Bach could have begun to reuse old cantatas—but instead he completed a whole second cycle and most of three additional cycles. Bach had also written church cantatas at several of his previous jobs. However, none of his church cantatas were ever published. As a result, about two hundred are extant today, while hundreds more might have been lost.

A cantata is a multi-part work for voice(s) and instrumental accompaniment. Bach’s Lutheran church cantatas are multi-movement works for choir, soloists, and orchestra. Bach always used texts in German, the language of his congregation. He did not write the texts himself, however, but rather selected them from among the works of various theological poets. Each cantata is thirty to forty minutes long and usually contains four to seven movements. Some of the movements use the entire choir, while others feature solo singers, often paired with solo instruments.

Bach’s cantatas constituted the musical focus for worship at St. Thomas and other churches in Leipzig. Although forty minutes of choral music might seem excessive, the services themselves lasted four hours. The centerpiece was a one- hour sermon, which was preceded by opening prayers, hymns, readings, and the performance of the cantata. Communion followed the sermon.

The cantata had a very specific purpose: It reflected on the Biblical readings for the day, interpreted their meaning for the congregation, and prepared listeners to understand and appreciate the sermon. As stated above, Bach in no way regarded his cantatas as entertainment—or even, strictly speaking, art. He was deeply committed to his Lutheran faith and he understood his role in the service to be essentially spiritual. His cantatas shaped churchgoers’ understanding of their relationship with God.

We will see Bach’s approach to cantata composition in Sleepers, Wake. Although many of Bach’s cantatas are difficult to date, we know that this one was first performed on November 25, 1731. The occasion was the 27th Sunday after Trinity—a day that occurs only in years during which Easter falls very early, for in regular years the liturgical season of Advent will have already commenced. This explains why Bach had to write this cantata several years after having completed his annual cycles, for the 27th Sunday after Trinity had not occurred since 1704. Sleepers, Wake was performed only once in Bach’s lifetime, at Leipzig’s St. Nicholas Church. The Epistle reading for the 27th Sunday after Trinity is 1 Thessalonians 5: 1-11, while the Gospel reading is Matthew 25: 1-13. Both exhort Christians to be prepared for the return of Christ. In Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians, he warns that the Lord will come “like a thief in the night,” without any warning. Matthew records the parable of the wise and foolish virgins. All had gathered together to await the coming of the bridegroom (an allegory for Christ), but the foolish virgins had failed to bring extra oil for their lamps. While they were away buying oil, the bridegroom arrived and the wedding feast commenced. The wise virgins, who were prepared for the arrival, were welcomed into the hall, but the foolish virgins were shut out in the darkness. The message is clear: Christians must be prepared for Christ’s coming. If they are not, they will be excluded from heaven and denied eternal life.

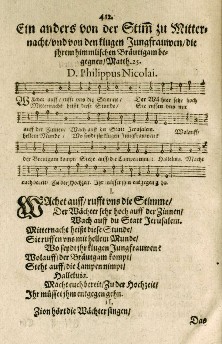

Bach’s cantata reflects on this parable using a variety of musical and dramatic techniques. He began by selecting an appropriate Lutheran chorale on which to base his cantata. Chorales are unison hymns sung by the congregation, and they were first developed by Martin Luther himself in the early years of the church. One of Luther’s objections to Catholic worship was that the music was performed in Latin by professional choirs. He preferred participatory music in the language of the congregants. To develop a repertoire of chorales, he wrote new tunes, adapted Gregorian chants, and even borrowed popular melodies. Luther saw no problem with using secular music for worship. As he supposedly put it, “Why should the devil have all the good tunes?”

Because Sleepers, Wake is based on a Lutheran chorale, it is a special type of cantata known as a chorale cantata. Bach primarily wrote chorale cantatas while in Leipzig, and he developed a unique approach to their construction, of which Sleepers, Wake is a fine example. The cantata contains seven movements, three of which—the first, fourth, and seventh— include text and music from a 1599 chorale of the same name. Bach selected this chorale because it, too, comments on the parable of the wise and foolish virgins, thereby offering another layer of interpretation. Everyone in the congregation at St. Thomas would have known the chorale well and would have instantly recognized the words and music. Because the chorale is in A A B form, each of the movements based on it is in that same form.

I. Wake up, the voice calls us

Bach spreads his references to the chorale throughout the cantata, and he integrates it with his own music differently on each occasion. In the first movement, we hear the choir sing the first verse of the chorale text:

Wake up, the voice calls us

of the watchmen high up on the battlements, wake up, you city of Jerusalem!

This hour is called midnight;

they call us with a clear voice:

where are you, wise virgins? Get up, the bridegroom comes;

Stand up, take your lamps! Hallelujah! Alleluia!

Make yourselves ready for the wedding,

you must go to meet him!

Translation by Francis Browne

We also hear the chorale melody, but it is buried in a dense texture of newly- composed music. While Bach’s congregation would have recognized the chorale, many modern listeners have a hard time even picking the melody out.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Ritornello |

The violins and oboes exchange melodic material in a call-and-response texture |

|

0’28” |

A “Wake up, the voice calls us...” |

The sopranos sing the chorale melody while the altos, tenors, and basses sing newly-composed material |

|

1’32” |

Ritornello A |

This ritornello is identical to that which opened the movement |

|

2’00” |

“This hour is called midnight...” |

The A music repeats with a new texts |

| 2’10” | Episode | This is the most diverse and lengthy episode |

| 2’31” | Subject Heard in the bass; the tempo slows before the final cadence | |

|

3’04” |

Ritornello |

This ritornello sounds different because it moves through several key areas |

| 3’24” | B | “Get up, the We hear exclamations of “get up” and “stand bridegroom up” from the choir comes...” |

| 3’57” | “Alleluia!” This passage is especially ornate; the chorale melody does not enter until near the end | |

| 4’42” | “Make yourselves The texture returns to normal ready...” | |

| 5’32” | Ritornello | We hear the complete ritornello one last time |

The first movement starts with orchestral music, the uneven dotted rhythms of which suggest a wedding march. Dotted rhythms were also associated with royalty in this era—another appropriate connotation for music about Christ’s coming. This opening passage is in fact a ritornello. In this movement Bach combines ritornello form, in which an orchestral melody returns throughout a piece of music, with the A A B form of the chorale. The resulting form is: rit A rit A rit B rit. The orchestra also provides short interjections between the verses within each section. Although a congregation might sing the first verse of the chorale in less than two minutes, the first movement of the cantata takes nearly four times as long to perform. This is due to the slowed-down chorale melody and frequent orchestral interruptions. As a result, however, the congregation has an opportunity to meditate on the text, the meaning of which is reinforced by Bach’s musical setting.

The first movement is texturally very dense. There are active parts for strings, winds, and voices, and it is seldom possible to identify a single, dominant melody. The opening ritornello contains three distinct layers. Underpinning everything is the basso continuo, a feature of almost all music composed in the Baroque era (1600-1750). Basso continuo is always performed by some combination of low- pitched instruments and instruments that can play chords. In this case, we hear cello, bassoon, organ, and harpsichord. While Baroque bass lines can be simple, Bach’s seldom are. This one contains a variety of interesting rhythmic and melodic elements, thereby attracting an unusual amount of the listener’s attention. Above that, the violins and oboe trade melodic motifs back and forth in a six-part texture. When the singers enter, the orchestra begins by repeating the musical material from the ritornello. The already-dense texture suddenly becomes much more complex. First we hear the sopranos with the familiar chorale melody. While the sopranos sing in slow, even note values, the altos, tenors, and basses sing quickly. These other voices occasionally integrate text painting as well, such as with their ascending cries on the text “wake up”. Also notable is the passage on the text “Alleluia,” which features excitable melismas in the altos, tenors, and basses.

|

ritornello orchestra |

A from chorale |

ritornello orchestra |

A from chorale |

ritornello orchestra |

B from chorale |

ritornello orchestra |

|

lines 1-3 of text with accompaniment |

lines 4-6 of text with accompaniment |

lines 7-12 of text with accompaniment |

IV. Zion hears the watchmen sing

The chorale disappears until the fourth movement,2 when we hear the second verse sung by the tenor section:

Zion hears the watchmen sing, her heart leaps for joy,

she awakes and gets up in haste.

Her friend comes from heaven in his splendour, strong in mercy, mighty in truth.

Her light becomes bright, her star rises.

Now come, you worthy crown, Lord Jesus, God’s son!

Hosanna!

We all follow

to the hall of joy

and share in the Lord’s supper.

Translation by Francis Browne.

|

IV. “Zion hears the watchmen sing” from Sleepers, Wake 2. Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach Performance: American Bach Soloists (2007) |

This movement is much simpler than the first movement. In place of the orchestral ritornello, with its call-and-response texture, we have a unison ritornello melody from the violins and violas. The chorale melody, instead of being buried in a complex texture, is clearly presented without competition from other vocal parts. All the same, this movement is by no means simple. The two melodies—one in the strings, one in the tenors—weave around one another in unpredictable and extraordinary ways. While their phrases never start or end together, the parts always complement one another.

VII. May gloria be sung to you

We finally hear a straightforward presentation of the chorale in the seventh movement,3 in which the entire choir—and perhaps the congregation as well—sing the third verse in four-part harmony:

May gloria be sung to you

with the tongues of men and angels, with harps and with cymbals.

The gates are made of twelve pearls, in your city we are companions

of the angels on high around your throne. No eye has ever perceived,

no ear has ever heard such joy.

Therefore we are joyful, hurray, hurray!

for ever in sweet rejoicing.

Translation by Francis Browne

|

VII. “May gloria be sung to you” from Sleepers, Wake. 3. Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach Performance: American Bach Soloists (2007) |

Although Bach borrowed chorale melodies from the Lutheran tradition, he always created his own harmonizations. In practice, this means that the soprano part is borrowed, but the alto, tenor, and bass parts are original. Bach has the orchestral musicians double the vocal parts, playing the same melodies that are being sung. This makes the ensemble sound exceptionally full and rich without distracting from the chorale melody: a fitting culmination to the cantata.

II. He comes

Although there are four movements that do not contain the chorale melody or text, we will look at only two of them. The text was supplied by an unknown poet. It includes many references to the Song of Solomon—a passage of Biblical love poetry that was understood by Bach and his contemporaries to be a metaphor for the love between Jesus and the faithful soul. To set this expressive new text, Bach used musical forms from the opera stage: recitative and aria. Bach never wrote an opera and did not think highly of the form, but he often adapted operatic conventions for his own purposes.

The second movement4 of Sleepers, Wake is a recitative for solo tenor:

He comes, he comes, the bridegroom comes!

You daughters of Zion, come out,

he hastens his departure from on high to your mother’s house.

The bridegroom comes, who like a roedeer and a young stag

leaps on the hills

and brings to you the wedding feast.

Wake up, rouse yourselves to welcome the bridegroom!

There, see, he comes this way.

Translation by Francis Browne.

|

II. “He comes” from Sleepers, Wake4. Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach Performance: American Bach Soloists (2007) |

He announces the coming of the bridegroom with a series of exuberant melodic leaps, accompanied only by basso continuo. This movement contains no repetition and has no particular form. In fact, the singing—as is always the case with recitative—is not particularly melodic at all. Instead, its purpose is to declaim the text with the utmost expressive force.

III. When are you coming, my salvation?

The recitative serves to introduce the third movement, which is a duet for soprano and bass. Just as recitative developed within the operatic tradition, this is clearly an operatic duet—specifically, the type of duet sung by two characters who are in love. The soprano and bass call back and forth to one another, expressing their mutual desire. Bach’s lovers, however, are a Soul (soprano) and Jesus (bass), and they offer a dramatic enactment of the desire that all Christians are meant to feel for their savior.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Ritornello A |

This ritornello features a virtuosic violin obbligato |

|

0’26” |

“When are you coming. . .” |

The soprano and bass exchange lines while the solo violin line weaves about them |

|

1’46” |

Ritornello |

This ritornello is similar to that which opened the movement, but it is in a different key |

|

1’59” |

B “Open the hall. . .” |

This passage has the same texture as A, but the music and text are different |

|

2’32” |

Ritornello |

This passage is not closely related to the opening ritornello |

|

2’46” |

B’ |

This passage is similar to B, but it is in a different key |

|

3’18” |

Ritornello A’ |

This ritornello is very brief, for it is interrupted by the return of the A text |

|

3’25” |

“When are you coming. . .” |

This passage echoes A, but is not musically identical |

|

4’25” |

Ritornello |

The closing ritornello is identical to that which opened the movement |

Because the third movement is based in operatic conventions, it has the da capo form of an opera aria. “Da capo” literally means “from the head,” and it serves as an instruction to the performers to repeat the first of two parts, resulting in an A B A form. (The second A is not written out.) Bach accompanies his aria with basso continuo and an obbligato (or “obligatory”) instrumental solo. He intended the obbligato part in the fourth movement to be performed on the violino piccolo, a type of small violin that is tuned higher than a modern instrument. However, it can also be performed on a standard violin. The instrumental soloist provides ritornellos before, between, and after each of the sung sections, but also supplies a virtuosic accompaniment to the vocal soloists. The resulting music is beautiful and expressive—even if the text is a bit corny:

Soul: When are you coming, my salvation? Jesus: I come, your portion.

Soul: I wait with burning oil. Jesus: Open the hall

Soul: I open the hall

Both: to the heavenly feast. Soul: Come, Jesus!

Jesus: Come, lovely soul!

Translation by Francis Browne.