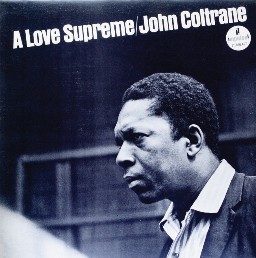

11.6: John Coltrane - A Love Supreme

- Page ID

- 92186

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

All of the compositions we have examined in this chapter were originally intended for practical use in a worship service. In our exploration of “Amazing Grace,” however, we encountered instances of performances—Aretha Franklin’s, for example—that brought the hymn into less formal realms. Franklin’s concerts probably provided a worship experience to some of those present, and her performance was an expression of deeply held belief. The essential purpose of the concerts, however, was to create a commercial recording, which is in turn available for consumption as entertainment.

With our final example, we will encounter a similar instance of personal belief influencing the commercial output of a performing artist. John Coltrane’s album A Love Supreme (recorded in 1964, released in 1965) was certainly never intended for use in a place of worship. All the same, it was clearly intended by the performer as an act of worship, although the specifics of Coltrane’s belief system—outlined below—continue to elude researchers.

John Coltrane (1926-1967) was one of the great jazz innovators of the 20th century. He began playing saxophone as a teenager in Philadelphia. Coltrane joined the Navy during World War II, where his talent was recognized and he received the rare honor of being permitted to play with the base swing band even though he had not enlisted as a musician. Upon leaving the military, he toured with various bands and began to meet and play with the jazz luminaries of the era. “Giant Steps” (1959) is perhaps Coltrane’s most famous composition—and performance.

Coltrane began his post-war career playing bebop, a high-intensity form of jazz in which virtuosic soloists exhibit their skills. Bebop is performed by jazz combos—small ensembles with a single performer per instrument. A combo will almost always include piano, bass, and drums, with the addition of one more players on a melody instrument (saxophone, trumpet, and trombone are the most common). In bebop, the combo will begin by playing a set melody, usually underlaid with complex harmonies. This composition is termed a head and is notated on a lead sheet. Then the members of the ensemble will take turns improvising solos over the chord progression. Coltrane composed and recorded perhaps the most difficult of all bebop heads, “Giant Steps,”8 in 1959 (released on the album Giant Steps in 1960).

Like many jazz musicians of the era, Coltrane struggled with drug and alcohol abuse, and he became a heroin addict. In 1957, however, Coltrane quit heroin cold turkey, locking himself in his Philadelphia home to battle withdrawal. He later described “a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life.” He indeed went on to produce his greatest work, and religious themes would increasingly dominate his music for the rest of his career. Coltrane’s most compelling spiritual statement, by all accounts, was his 1965 album A Love Supreme.

In the liner notes to A Love Supreme, Coltrane described his 1957 experience: “At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music. [. . .] This album is a humble offering to Him. An attempt to say “THANK YOU GOD” through our work, even as we do in our hearts and with our tongues.” There is no doubt that Coltrane intended his album as an expression of his profound spiritual thanksgiving to god—but it is not clear exactly who or what “god” was to Coltrane.

Both Coltrane’s maternal and paternal grandfathers were pastors in the African Methodist Episcopal church, and there is no doubt that his childhood experiences with Christian worship influenced both his beliefs and musical expression. However, Coltrane became increasingly interested in non-Christian spiritual beliefs in his adult years. His first wife, with whom he maintained a close friendship even after they divorced, was a Muslim convert. Later he took to studying Eastern religions, and he was known to pore over the religious texts of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism with equal fervor. In the liner notes to his 1965 album Meditations, Coltrane stated bluntly, “I believe in all religions.”

A Love Supreme is in four parts: “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm.” For this reason, the complete work is often described as a suite. The parts range from seven to eleven minutes in length, and were recorded in a single session on December 9, 1964. The performers, in addition to Coltrane, were McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass, and Elvin Jones on drums. This ensemble, known today as the “classic quartet,” recorded many of Coltrane’s greatest albums. Although A Love Supreme is generally regarded as a unique artistic work that cannot easily be categorized, it can also be understood as an example of modal jazz. In modal jazz, the traditional chords of bebop are replaced by harmonies built on modal scales—those other than major and minor. With the emphasis shifted away from harmony, performers focus more on melodic development, rhythmic intricacy, timbral variation, and emotional expression. Examples of modal jazz tend to be slower and more exploratory than bebop recordings. Throughout, A Love Supreme avoids explicit melodic statements or clear rhythmic frameworks. There is no “tune,” and the listener cannot easily find a downbeat or identify the meter. Instead, the recording gives the impression of transcending the confines of “jazz” and offering a window directly into the players’ souls.

“Acknowledgement”9 opens with the reverberation of a gong and cymbal rolls. Out of this wash of sound emerge Tyner’s piano chords and Coltrane’s improvisation on a four-note figure. Next we hear the primary theme of the album: a four-note, repeated motif played by Garrison on the bass. When Coltrane enters again, it is with the same four notes we heard him play at the opening of the track. He slowly adds notes and builds in energy, eventually using the technique of overblowing to create squawking notes in the high range of the instrument. We hear the same rhythmic patterns again and again throughout his solo. Finally, Coltrane plays the four-note motif from the bass again and again, in dozens of different keys. The track concludes with members of the combo singing the motif on the text “a love supreme” before Garrison plays a closing bass solo. By singing, the performers reveal what had hitherto been a secret meaning behind the motif that dominates the composition.

|

“Acknowledgment” from A Love Supreme. 9. Composer: John Coltrane Performance: The John Coltrane Quartet (1964) |

The final part, “Psalm,”10 also has a secret text. This time, the text is a poem of praise authored by Coltrane and included in the album’s liner notes. It uses phraseology and language that is familiar from Christian worship, but at no point does it explicitly indicate that Coltrane is worshipping the Christian god. Similarly, the title “Psalm”—a reference to the Psalms of Christian and Jewish tradition— clearly refers to something other than a literal Biblical Psalm. Although there is no sung text in the recording, the listener can easily follow the words as Coltrane plays, since his phrasing closely matches that of the poem.

|

“Psalm” from A Love Supreme. 10. Composer: John Coltrane Performance: The John Coltrane Quartet (1964) |