3.4: Localizations

- Page ID

- 172103

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Mediated Selves Mixing Musics

We have seen throughout this book that through migration and media, people have moved musics and blended them into new combinations. Instances of border-crossing or musical borrowing are more norm than exception. The terms people use to discuss global movements of people and music, like deterritorialization (moving the music out of its place of origin) and localization (settling the music into a new location), can make this movement sound like an orderly process, like snipping out a patch of fabric and sewing it on somewhere else.

These terms also tend to leave the individual out of the frame, treating the movement of music as a by-product of global forces. The impersonal nature of these terms reflects the tendency, prevalent since World War II, to see the world as a “system” and to think about its workings using technological language. The idea of modernization—bringing all world systems into efficient alignment—predates this period, but the worldwide institutions that support modernization came into existence during the United Nations era. The engagement of international corporations in creating and maintaining “labor forces” that serve their purposes, the remaking of persons as “consumers,” and measurements of economic productivity all manifest this kind of thinking. Likewise, by conveying information to vast audiences, our communications systems incorporate individuals into larger wholes, whether those be nations, states, political parties, or other groups. This top-down, system-oriented view may suggest that technologies such as broadcasting, the digital music file, and the internet cause music to move along paths made by globalized states and corporations.1

The idea of a UN-style showcase of “cultures,” discussed in chapter 5, also manifests “world systems” thinking. It presents an orderly picture of the world in which each group of people is distinct, known, and valued. The United Page 203 →Nations has long encouraged the view that each country has “the right and the duty” to safeguard both tangible works of art and intangible cultural heritage—that is, “oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts.”2 As we saw with Mexico’s Ballet Folklórico in chapter 5, in the UN era states and peoples have made it standard practice to represent themselves by performing heritage. Furthermore, the United Nations has urged its member states to make laws that discourage alteration of musical traditions and to found institutes for their preservation. Nation-states have embraced this idea: many have honed their individual brands by packaging their heritage for consumption by others through media or tourism. Although the UN system promotes the “modernization” that would bring many nations into similar forms of governance, at the same time it also fosters this well-contained traditionalism.3

The idea of modernization is troubling, since it involves comparing all the world’s peoples to Europe or the United States and finding them lacking.4 Seeing the world as a system in this way can also lead us to think in rigid ways about groups of people. The philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah notes that early in the United Nations era, in 1954, a number of countries signed an agreement ensuring the protection of “cultural property” during wartime (the Hague Convention). Many works of art had been destroyed during World War II. The countries that signed the convention promised to try to preserve the arts rather than destroying them. The Hague Convention says that “each people makes its contribution to the cultures of the world.” Appiah observes:

That sounds like whenever someone makes a contribution, his or her “people” makes a contribution, too. And there’s something odd, to my mind, about thinking of Hindu temple sculpture or Michelangelo and Raphael’s frescos in the Vatican as the contribution of a people rather than the contribution of the individuals who made (and, if you like, paid for) them. . . . This is clearly the wrong way to think about the matter. The right way is to take not a national but a trans-national perspective—to ask what system of international rules about objects of this sort will respect the many legitimate human interests at stake.5

As Appiah sees it, we lose something important when we think of a work of art as belonging mainly or only to its country or people of origin. Often, especially in a mediated world, art has meaning not only for the group to which Page 204 →the art’s maker belongs but also for many people outside that group. Appiah believes that these art lovers, too, should be taken into consideration.

Appiah’s observation points to the complexity of individuals’ artistic practices and attachments in a mediated world. When individuals make music, they may or may not be thinking about representing their own groups, whether national, ethnic, or otherwise. As we have seen (chapter 6), musical allegiances may be inherited, but they can also be chosen. People have personal wishes for how music should sound; they connect to a variety of traditions; they respond to their local markets and the desires of audiences. It is tricky to understand what is going on here: to get a grip on worldwide phenomena, like colonialism or globalization, it is useful to see the big picture. At the same time, the only way to know what those phenomena mean is to see how they play out in the lives of individuals or neighborhoods.

This chapter introduces some diasporic Korean people whose individual musical choices reflect a variety of artistic allegiances. We will also meet musicians from South Africa, Morocco, and Egypt who have adopted hip-hop from afar. These people are globally connected, yet their music-making also offers us insight into their specific local and personal situations. In thinking about these individuals and their particular kinds of connectedness in a diasporic and mediated world, we will see that heritage and tradition become flexible concepts. Members of diasporas relate to their histories and their families’ historic places of origin in complicated ways. They may travel or learn a language to reconnect with their families’ places of origin, study genealogy, take up a musical practice that is also valued in the place of origin, change their inherited music to fit a new context, or seek to assimilate in their current homes. We will also see that, in a mediated world, individuals may, for their own reasons, become deeply attached to music originating elsewhere, and that attachment may itself generate further long-distance contacts through travel or media.

The anthropologist Nestór García Canclini can help us understand all this complex motion. He defines “hybridization” as a strategic process in which people choose to blend practices that used to be separate, generating something new. This process can include the adoption of an existing musical practice by new people or the purposeful blending of styles. According to Canclini the mixing of musics does not result from an impersonal global process but from individual and group creativity. People change their artistic practices, affiliating themselves with unfamiliar musical traditions or renovating heritage to tell a new story about the present day.6

Whether it happens by taking up a new kind of music or by making a Page 205 →mixture of musics, that change in practice is a form of appropriation—the “taking to oneself” of music that was not originally one’s own. In Canclini’s view, when individuals creatively reuse or adapt music, that process need not be regarded as theft. Rather, Canclini calls those reuses “strategies for entering and leaving modernity.” By modernity Canclini means the European vision of cosmopolitan modernity developed during the long era of colonialism, for that idea has had enormous influence in many places. Like the self-concept of the Europeans who visited the Paris Exposition in 1889, this vision of the modern may include an industrialized economy, the use of ever-advancing science and technology, a well-functioning administrative state, and styles of music that change rapidly in their movement toward the “new.” Whereas Europeans used this idea to separate themselves from peoples they deemed “primitive” (chapter 1), many non-Europeans also adopted the “modern” as a standard by which to measure their own lives and societies (chapter 5). Like the idea of race or the concept of authenticity, this idea of what is “modern” has no basis in fact: it is a story people have told to create, enforce, and explain social divisions among groups of people.

Canclini sees that people in formerly colonized parts of the world routinely apply the categories of the modern (universal, global, changing) and the traditional (particular, local, unchanging—“the folk”). Yet in the postcolonial world people’s experiences are neither “all modern” or “all traditional”: most lives encompass some combination of the two. By adapting or adopting music, individuals can participate in what feels new, or what feels like heritage, or both. Through art artists define their own positions with respect to other art—which can mean choosing styles that represent a particular perspective as universal or local, modern or traditional.7 The many people who live in that “in between” or mixed state use music to define and express the complexity of their situations. More broadly, any time we see appropriation, we may want to ask, When this artist mixes musics, what kind of world is the artist entering (or creating), and what is she or he leaving behind? Appropriations and mixes are commonplace and not always abusive; these practices can embody a host of emotions and perspectives.

A Mediated Diaspora: Koreans and Korean Americans

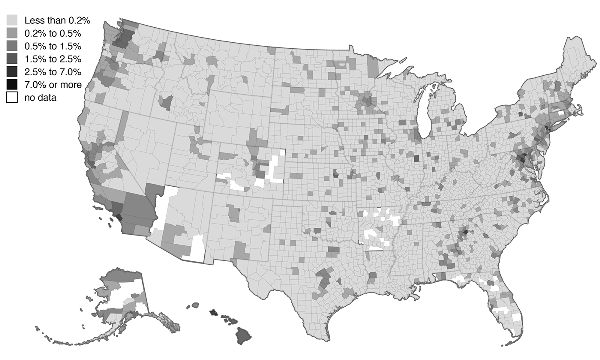

We can see some of that complexity in the musical lives of diasporic Koreans. According to the US 2010 census, 1.7 million people of Korean descent live in Page 206 →the United States; another 100,000 live in Canada (fig. 8.1).8 The migration of Koreans to the United States is closely tied to the history of military, political, and religious connections between the two countries. Protestant Christian missionaries from the United States began to arrive in Korea in 1884, introducing their church music along with their religion. Between 1901 and 1905 the missionaries encouraged emigration to the US. They recommended that sugar planters conscript Korean people and bring them to the US colony of Hawaii as low-wage laborers. Korean Christians also came to the mainland US in search of education. During the Japanese colonial occupation of Korea (1910–45) the occupiers took many Koreans by force or deception to work in Japan, especially during wartime (1939–45). Only a small number of Korean people came to the United States during this period. Between 1945 and the end of the Korean War (1953), the United States military occupied the southern part of Korea, the Soviet Union the northern part: these occupations established political and musical relationships that supported later travel and migration patterns.9

After the Korean War about 100,000 Korean women and children entered the country as family members of American soldiers. Afraid that South Korea would turn toward communism, the United States continued to provide aid for economic development, including bank loans and support for building a capitalist economy based on manufacturing. US officials also offered unofficial support for Christianity in South Korea, as they believed religion was a safeguard against the secularism of communism: today, about 30 percent of South Koreans practice Christianity. These business and religious relationships developed countless collaborative ties between US and Korean people, introducing a steady stream of international travel for university students, venture capitalists, managers, church pastors, and choral directors.10

In 1965 a new law, the Immigration and Nationality Act, changed how US government officials decided which immigrants to admit. Because racial discrimination had become an embarrassment for the United States in world public opinion, the act disallowed discrimination on the basis of race and national origin. Before 1965, US law purposefully gave white western and northern Europeans priority, but the new law used categories like professional training, close family relationships, and refugee status to establish immigration quotas. With this new protection in place many Koreans—especially doctors and others with in-demand skills—migrated to the United States in search of better opportunities.11 Still, some experienced a significant decline in wealth and social status on arrival in the United States.12

Page 207 →Today, some Korean Americans live in ethnic enclaves—that is, areas where a high concentration of Korean people live and work in close proximity, often doing business in the Korean language and retaining a strong ethnic identity that separates them from the surrounding community.13 Others have partly or fully assimilated, absorbing the language and practices of other US communities around them. One cannot assume that Asian Americans, or any other diasporic group, hold a primary allegiance to their Asian homelands; indeed, in the past this assumption has led to unjust persecution of loyal US citizens.14 There are probably as many approaches to being Korean American as there are Korean Americans: patriotism for the United States may be mixed with experiences of racial discrimination, nostalgia or curiosity about Korea, a variety of chosen and inherited musical preferences, and much more. While acknowledging the diversity of these experiences, we can observe some practices that are common among this diasporic population and shared with other diasporic groups as well.

Page 208 →Classical Circuits

The world of European-style concert music (or “classical” music) has long consisted of international circuits. We have seen that colonialism and modernization efforts took this music to new places. Since the 1700s, it has been possible for performers of concert music to make international reputations by traveling widely.15 After World War II these circuits became more geographically inclusive, and they have been shaped by political alliances. During the Cold War, Soviet Russia supplied North Korean, Chinese, and Eastern European orchestras with financial support, conductors, and soloists. The United States cultivated similar relationships with Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and Western Europe. And both the US and the USSR sought to build connections with nonaligned countries.16

According to the musicologist Hye-jung Park, European classical music was one way the United States strengthened its relationship with Korea. The US occupation government in South Korea sponsored a European-style orchestra. Korean educators and the US occupation government worked to include European-style concert music in new Korean school curricula. In fact, until recently, a Korean child could easily grow up with an extensive education in European concert music but no familiarity with Korean traditional music.17 Korean composers began to compose music to be performed by Western-style orchestras. In addition US officials offered individual Korean musicians grants that allowed them to visit the United States for training. Teachers and students remained in contact across the Pacific, reinforcing firm connections between Korean arts institutions and schools of music in the United States. For South Korean musicians, travel to famous music schools like the Juilliard School in New York became a mark of prestige. Grace Wang, an American studies scholar, writes that for many Asian and Asian American parents, participation in European classical music is a mark of inclusion in a prestigious and globally valued practice, as well as a sign of education and hard work.18

Even though Korea has excellent teachers of Western concert music, many young musicians have continued to travel to the United States. For decades the arrival of talented and meticulously trained musicians from Asia has aroused considerable media attention in the West. One of the earliest instances of international fame was the Chung family. Siblings Kyung Wha Chung, Myung Wha Chung, and Myung Whun Chung moved to New York with their parents in the 1960s to continue their musical training. They gained great fame, performing as a trio and as soloists. Kyung Wha Chung, who had Page 209 →already been famous as a child prodigy on the violin in Korea, studied at the Juilliard School from her early teens and at age 19 won a major international competition. In her early 20s she performed as a violin soloist with major orchestras in Europe and the United States. Her sister, the cellist Myung Wha Chung, developed an international career as a performer and teacher: she has taught at the Mannes College of Music in New York and the Korean National University of the Arts in Seoul.

Their brother, Myung Whun Chung, built an international career as a conductor, traveling to lead major orchestras in Europe, the United States, and Asia. He served as principal conductor of the Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra in Paris, and for ten years he was the music director of the Seoul Philharmonic. During his tenure in Seoul the German record company Deutsche Grammophon granted the orchestra a large recording contract. The Seoul Philharmonic was the first Asian orchestra to receive this much attention from a Western recording company. Chung’s response to the record deal was revealing: in an interview he said he hoped the deal would become a “footing for Seoul Philharmonic to become a world class orchestra.”19 Although Asian musicians have attained celebrity status throughout the international circuit, and Asian orchestras have performed very well for decades, a hierarchy persists. As the European tradition did not originate with Asian performers, people in the West have typically not regarded them as equal participants. The effort to “become” world-class has been part of Asian conversations about concert music for more than 60 years.20

Indeed, despite their conspicuous successes, many of these musicians have experienced discrimination. Some critics still make the racist charge that Asian performers may have technical merit but cannot understand or perform European music as a person of European descent can.21 Asian musicians’ adoption of European concert music seems to be one of Canclini’s strategies for “entering modernity,” but that entry is sometimes challenged. Blind auditions, in which judges hear musicians play but cannot see them, have increased access to orchestra jobs for members of racial minorities and women.22 Yet most performing opportunities cannot happen behind a screen. Although participants in classical music continue to view music as a meritocracy, slurs and stereotypes persist. Even in the age of globalization, music does not flow unhindered among peoples: race-based exclusion is one form of friction in the system.23

Despite the continuing bias against Asian musicians, Asia has become a vital site for the cultivation and preservation of the European concert music tradition. When an interviewer asked the Korean American violinist Sarah Page 210 →Chang about declining ticket sales for classical music in the United States, Chang responded, “I’m actually not too worried about this at all. Take my concerts in Hong Kong: they’re sold out.”24 The white American violinist Joshua Bell likewise reports tremendous audience enthusiasm in Asia for European-style concert music: “Whenever I play in Korea, I feel like I’m at a rock concert.”25 Some critics in the US and Europe who value European-style concert music have mourned the demographic shift of interest in it to Asia, seeing it as a marker of decline of education and “values” in the West. Some talk about the “death” or “decline” of classical music, even though the music is evidently flourishing.26 Like the racist critiques of Asian performers, this mourning invokes the idea of heritage. Does classical music belong to Europeans and their genetic heirs, exclusively? Or should this tradition be passed along to anyone who wants to invest the time and effort, just as any tradition can be handed down?

If these questions were really about the past, we might note that European concert music was never a unified tradition, ethnically or otherwise. But like other arguments about heritage these questions are not really about the past or about ascertainable historical facts. Rather, they reflect a use of the past by present-day people who are concerned about their place in the present-day world. To be sure, vestiges of the colonial past linger in the values of the present. As we saw in the cases of Japan and Turkey, in the 1800s and 1900s people outside Europe sought entry to the tradition because Europe seemed modern and powerful. Today, when people make the unfounded assertion that Asian musicians’ performances lack an undefined “special something” compared to white peers, they are protecting their exclusive connection to the prestigious music by policing others’ access to that music. When critics mourn the “death” of a music that is still living, they choose to ignore the contributions of Asian musicians and many others. The idea that concert music is a heritage that Europeans or European Americans can have, but Asians cannot quite fully possess, relies on the manufacture of an artificial difference between peoples.27

Participation in traditions is not inert or value-neutral. According to Canclini joining a tradition or combining traditions is a strategic act that places people into particular roles. A person can gain access to a tradition or be excluded from it; a person can take up a tradition or abandon it; a person can be made to feel superior or subordinate through their participation in a tradition. The very idea of prestige implies that only some people have access: and opening a tradition to anyone who wants it changes that social hierarchy, placing people into new and possibly uncomfortable roles. Thus, a discussion Page 211 →about heritage is one way that social differences can be maintained and conflicts can be played out: a place where the friction is visible.28

As Canclini has pointed out, though, attempts to draw firm boundaries separating “cultures” or groups are futile.29 Music undergoes “continuous processes of transculturation,” which the anthropologist Renato Rosaldo defines as “two-way borrowing and lending.”30 Seen from this perspective, the Asian adoption of Western music is a normal outcome of transnational interactions spanning more than 100 years. If people want to sustain the musical tradition, they might rejoice to see its worldwide adoption. But if they are invested in maintaining prestige or difference, they might instead continue to insist on using heritage or racial claims to draw boundaries. Because migration and media have deterritorialized and reterritorialized music, the relationships between the traditional and the modern, or between the central and the peripheral, are in flux.31 The transnational aspect of European classical music is no longer a footnote to its history: it is central to the tradition’s development in the 20th and 21st centuries. This destabilization of value and perspective, and the conflicts and frictions that come with it, are part of what people mean when they talk about globalization.

These conflicts and frictions also shape the work of composers of concert music. Hyo-Shin Na (1959–) is a Korean-born composer based in San Francisco, California. After studying piano and composition in Korea, she attended the Manhattan School of Music and the University of Colorado. She has traveled back to Korea repeatedly; there, she took up the study of Korean traditional music and East Asian music more generally. She maintains an active career in the San Francisco Bay area, and many organizations in that region have paid her commissions to compose pieces of music. She has won awards for her compositions on both sides of the Pacific.

Na has defined her Asian American identity with care. According to a recent liner note, Na has said, “I am no longer trying to write Korean music; nor am I trying not to write Korean music.”32 We can hear what Na means by listening to a piece entitled “Koto, Piano II,” composed in 2016. As the title implies, the music is a duet between a Japanese instrument, the koto, which is played by plucking and scraping the strings, and a European instrument, the piano, which strikes its internal strings with felt hammers. Each instrument offers a resonant quality, as the vibration of the strings takes a while to decay. Yet the different sound qualities of plucking and striking mean that this piece is never quite unified: the two instruments retain their identities as they coexist. For those who are familiar with Japanese music, or have heard it in films, Page 212 →the sound of the koto is strongly associated with Japan, and listeners may bring this association with them as they approach the piece.

This music, heard in example 8.1, encourages the two performers to listen very closely to each other and to play in close synchronization: for the first minute of the piece, they play nearly (but not quite) in unison. Next, they begin to play separately but echoing each other’s phrases, sometimes coming back together for a short while. At timepoint 1:34, and again at 2:47, they play a short refrain, a recurring section, in which their parts are not identical but fit together well. At timepoint 5:58 they play in unison again, then move apart once more as the piece comes to a close.

By the end of the piece the listener is accustomed to the interplay of sound qualities and may forget that the two instruments represent different musical traditions; the musicians perform as equals throughout the piece, and their play of sameness and difference seems to be amicable and cooperative.

Na’s paradox—not trying to write music marked as “Asian,” and not trying to not write such music—rings true for this work. The Asian instrument here (Japanese, not Korean) is integrated not as an exotic sound but simply as a way to make sound of equal importance to the chosen Western instrument, cooperating but not blending. The tuning of the koto means that its scale patterns will predominate, but the two instruments adapt to each other throughout. Like some of the examples of “next-generation mediated selves” we met in chapter 6, this music models a form of integration in which the origin of the instruments is less important than the sounds they make.

The transnational composer faces audience expectations that make all her compositional choices a little harder. If Hyo-Shin Na composes music that audiences find “stereotypically Korean,” she may run the risk of limiting her audience, being labeled as a specialty composer who only writes for Korean or Asian audiences. Yet the story line of “uncovering one’s heritage” or “returning to one’s roots” has become a powerful marketing tool that has demonstrated appeal for audiences—another use of the heritage idea in the present day. This story line takes the “difference” that many in US audiences still attribute to Asian people and converts it into an asset by marking this music as distinctive or authentic as compared to all other new compositions. Composing music Page 213 →that does not draw on the expected heritage could mean losing this useful branding device.33

Throughout her career Na’s strategy as a composer has been to create many kinds of music. The composition called Ten Thousand Ugly Ink Blots (example 8.2) bears no obvious markers of Asian identity. This piece, composed for a string quartet (two violins, viola, and cello), belongs to the genre called experimental music or New Music. (Though the genre is no longer new, its participants value modern novelty.) At the beginning of the piece the notes are separated from each other so that they sound like isolated points rather than a melody.

This strategy echoes modern Austrian music of the 1930s, such as Anton Webern’s String Quartet opus 28. Other pieces, like That Old Woman, rely more prominently on Asian musical instruments—used sometimes in traditional ways, sometimes unconventionally. Na has made herself hard to pigeonhole by offering many different approaches to music-making. She freely uses her own strategies for entering and leaving the Asian traditional music world and the New Music world. Sometimes she stands in the doorway between the two.

Na’s history is marked not only by assimilation of the musical practices of Euro-America but also by conscious and careful mixing of traditions, crafting a sensibility of multiple possible selves. This kind of cross-cultural thinking is not something that just happened to Na as a result of her migration; rather, it is a personal strategy for understanding and working with the challenges and opportunities that come with such a move.34

Traditional Music in the Global Flow

The ongoing relationship between some diasporic Koreans and the nation-state of South Korea has been cultivated by the South Korean government through music and heritage practices, with assistance from the US government and the United Nations. In the late 1940s the US occupation government in Korea sponsored a festival of Korean traditional music—that is, folk music. The festival helped reestablish a style of Korean percussion band music Page 214 →that had been suppressed during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Once called nongak—“farmer’s music”—the music is now more often called p’ungmul, reflecting the fact that it is no longer primarily a rural music.35 The devastation of the Korean War temporarily halted the music’s restoration, but after the war some Korean scholars and performers reinvigorated the tradition. They founded the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts to support research into old practices and courses in which people could learn to perform traditional music.36 As a revival of heritage, this new cultivation of p’ungmul did not precisely recreate what had come before; rather, it drew on the past in ways that made sense in the present. Whereas p’ungmul had once been an art practiced only by men, after 1958 the revival included all-female and mixed troupes. Since that time educational institutions have adopted p’ungmul into their curricula, protest movements have taken the music up as a populist symbol, tourist agencies have promoted it, and the South Korean government has supported its propagation through cultural institutions in Korea and abroad.37

P’ungmul originated as rural processional music involving drums, gongs, and wind instruments. The performers wear colorful costumes and festive hats, and they carry their instruments with them as they dance in circular, spiral, or zigzag patterns. The music is organized as a sequence of different rhythmic patterns, moving from slower patterns to faster ones. Both in Korea and in Korean American communities p’ungmul has been associated with festivals: the Lunar New Year, the May festival, the conclusion of the weeding of the rice in July, and the harvest in October.38

Between 1961 and 1979 the South Korean military government of Chung-Hee Park took stringent actions toward modernization of villages, abolishing a variety of village community rituals as “superstition.” At the same time, though, the state took steps to preserve “cultural heritage,” passing a Cultural Asset Preservation Law that supported further restoration of art forms the Japanese occupation had suppressed. These restoration efforts paralleled and were supported by the work of the United Nations. In 1972 UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) issued a Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Nation-states could apply to the UN for special status and funding that would aid the preservation of art forms that seemed in danger of dying out. UN recognition also brought the preserved art forms to the attention of tourists. Thus, the Korean government had an incentive to preserve at least some elements of older music.39

Page 215 →Official state recognition of “Important Intangible Cultural Assets” in Korea led to the institutionalization of p’ungmul and the sponsorship of national competitions that showcased it. P’ungmul performances became more standardized across the country. When a regional style gained national recognition, sometimes groups in other regions adopted that style, even though it did not originate in their region. By law, however, the government officially recognizes and cultivates five distinct regional styles of p’ungmul.40

One Korean p’ungmul group, called Rumbling Sound (Sori Ulrim), recorded this concert performance of p’ungmul in 2012 (example 8.3).41 This is a staged performance of p’ungmul: you can see the audience in the background, seated around the stage. The words on the backdrop say “Our Melody, Our Courtyard,” pointing to the traditional setting for p’ungmul: the wording is purposefully antiquated, directing the listener to notice the traditional nature of this performance.

The first performers to enter after the banner play soe, small handheld gongs. Their part moves fast and articulates a rhythm based on fast groupings of three pulses. The players alternate between different patterns within that overall plan of pulses, so the crashing sound of the soe fills the air all the time (see fig. 8.2). The lead soe player directs the music-making of the entire p’ungmul group and decides when they should change to a different rhythmic pattern. Next in line we see two players carrying ching (larger gongs); their part simply marks the first beat of each cycle of pulses. The players who follow play the changgo—hourglass-shaped drums—with thin sticks. Then come the puk: circular, deeper-sounding drums that keep the beat. Several sogo players enter next. The sogo is a small, double-headed drum held by a handle; it contributes some sound to the pattern but largely serves as a dance prop. Difficult to see but easy to hear is the hojŏk, a cone-shaped wind instrument with a reedy tone. The hojŏk plays a nearly continuous and emphatic melody that lines up with the rhythmic pattern set out by the rest of the ensemble.42 The groupings of three pulses within each beat are especially effective, as they coincide with the circular swinging of the ribbons draped from the players’ hats. The overall effect, cheerful and celebratory, is suitable for a parade.

Once the entire group is onstage, at timepoint 0:54, the entire rhythmic Page 216 →pattern changes: the new pattern is based on groups of two rather than three. A p’ungmul performance typically consists of several sections lasting between one and 10 minutes, each with distinct music and dance. A piece structured in this way is flexible: sections of music can be extended as long as necessary, and new sections can be added as needed. This flexibility makes the music suitable for neighborhood performance: a piece of music may last as long as it takes to walk to the next destination. As the performance continues, the ensemble moves into different formations, and the dancers perform more athletic steps and leaps, as well as more intricate maneuvers with the ribbons.

In Seoul the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts is now part of the government’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism. This agency seeks to popularize p’ungmul within Korea, sponsoring a variety of performances and educational events. A revived form of p’ungmul is also practiced by urban clubs in Seoul.43 Since the 1970s, the Korean state has also fostered the practice of traditional Korean music in the United States.44 The Ministry of Culture and Tourism operates two cultural centers in the United States, one in New York City and one in Los Angeles; these cities feature large enclaves known as “Koreatowns.” These cultural centers mediate Korean music to people in the United States. With a primary aim of encouraging tourism among the general public, the Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles conveys a selection of “heritage” practices: traditional music, dress, martial arts, and cooking. Jiwon Ahn, a scholar of film, has called this selection a “standardized” and “touristy” image of Korea.45 At the same time, the center also offers programs that support the Korean American community, including concerts and exhibitions. Second- and third-generation Korean Americans learn the Korean language at the center, as do interested people who are not of Korean descent.

Page 217 →The practice of Korean music extends into the communities around the cultural centers. The ethnomusicologist Soojin Kim has described p’ungmul performances in New York and Los Angeles Koreatowns. Some of these performances purposefully preserve the ritual quality of village p’ungmul. Kim observes that collegiate p’ungmul groups in Southern California come together at the Lunar New Year and follow a tradition called chishinbalkki, which the Park regime marginalized in rural Korea. The group parades to local Korean-owned businesses (fig. 8.3). They perform p’ungmul at each shop they visit, and they give the shop owners a pokjori, made from two bamboo ladles, a symbol of luck to be hung on a wall. The performers also ask for donations to be used for projects benefiting the Korean community. Regardless of their ability to speak Korean, the students also learn to say New Year’s greetings in a traditional dialect so they can greet community members. These US college students offer a variety of reasons for their participation in the New Year’s ritual: community building, having fun in a group, supporting the Korean community, bringing good fortune to others, and experiencing or expressing a connection to Korean heritage.46

Other p’ungmul performances in the United States and Korea do not share this ritual function, although they may serve as entertainment, build community, or display elements of Korean heritage for non-Korean people. Every October in New York, a Korean newspaper sponsors an annual Korean parade and festival along Broadway, in which p’ungmul performers play. A similar parade takes place in Los Angeles: “a variety of Korean American associations, churches, community organizations, Korean bank branches, companies, and performing arts clubs have a procession through the street.”47 Kim has also documented a p’ungmul Christmas party in New Jersey and visits to schoolchildren that offer p’ungmul as an introduction to Korea.

In the village practice of the 1800s in Korea, p’ungmul was taught as oral tradition, passed down in memorized form from teacher to student. Today, it is much more commonly learned in classes and collegiate clubs or through textbooks and audiovisual media.48 P’ungmul cultivates tourism: many p’ungmul practitioners in the United States, especially American-born Korean people, travel to Korea to attend workshops and performances. It is also difficult to acquire Korean instruments in the United States; therefore, US performers have an incentive to go to Korea to select instruments. Korean p’ungmul experts also travel to give intensive workshops in the United States.49

As teachers of p’ungmul are comparatively few in the United States, the circulation of media provides essential support for Korean American p’ungmulPage 218 → performers. Korean media circulate through Korean ethnic enclaves in the United States: grocery stores in these enclaves sell compact discs and DVDs, and Korean Americans use the internet to watch Korean TV and movies. Some report a wish to maintain a connection, a feeling of “keeping up” with Korea as a homeland. Members of the Korean diaspora are numerous and form an important audience for media produced in Korea.50

In the global circulation of p’ungmul we can see how individual desires and institutional supports make possible a transnationally connected form of diaspora for Koreans and Korean Americans. Through media and travel, participants on both sides of the Pacific Ocean take part in this musical tradition. That the chosen music is village (folk) music is not coincidental. The efforts of the Korean government and the United Nations have encouraged individuals to connect to village music as heritage—a reuse of the past that is meaningful to them in the present day. In p’ungmul Korean Americans can participate in an imagined heritage by entering into a folk practice or, in Canclini’s terms, “leaving modernity.” At the same time, the transformation of p’ungmul and related genres into an international business supported by the South Korean Page 219 →nation-state suggests that the music has become a way of entering the showcase of global modernity envisioned by the United Nations.51

Hip-Hop as a “World Music”

The emergence of rap music as a global form has similar strategic qualities. Beginning in the 1970s, African American and Latinx youth in New York developed an expressive style of spoken-word music—rap—that articulated their experiences in a compelling way. The rap artist, or MC, often speaks from a first-person perspective. Sometimes the MC’s words make stories of hardship, conflict, or violence feel genuine and immediate, while also insisting that the speaker has the strength and resourcefulness to survive and even flourish; sometimes rap music is celebratory. In the words of political scientist Lakeyta Bonnette, “Rap music continues the cultural tradition of using the power of the spoken word to discuss political and social issues, advance attitudes, raise consciousness, and assert a political voice.”52 Rap is part of a larger set of practices called hip-hop that set these musicians apart: hip-hop artists choose particular styles of gesture and dance, typically wear baggy clothes and backward caps, practice turntablism, and may even incorporate graffiti into their routines, using spray paint to write on neighborhood walls. All these elements identify hip-hop participants as outsiders to a white mainstream society in the United States. This music offers a strong sense of voice: telling a variety of stories from a clearly defined and purposefully local point of view.53

Queen Latifah’s “Just Another Day,” from her 1993 album Black Reign, exemplifies that sense of voice. The song describes specific problems in troubled neighborhoods in New York—citing the neighborhoods by address so that the listener recognizes the singer’s precise place.54 Ironic quotation from the children’s show Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood (“Well, it’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood, a beautiful day in the neighborhood”) contrasts painfully with mention of a child killed by a stray bullet. Latifah celebrates the neighborhood with a sense of ownership and claims it as beautiful despite its perils. Latifah’s narration also asserts mastery over the situation: “I come with the real life perspective and rule / Me and my peoples from around the way remain cool” (example 8.4). Coupled with Latifah’s strong stage presence, the song conveys a sense of survival in the face of difficulty and seems to speak from the local (the neighborhood) toward the rest of the world through audio and video mediation.

Once rap gained a foothold in the national and international media, African Americans were able to convey powerful words about their experiences to people unfamiliar with their neighborhoods. Rap also became a means to demand political recognition and change. Through art, rap has often corrected the misunderstanding and misrecognition of African Americans and constructed a better representation of their lives. This representation is not just a matter of image: it has real consequences. States and other legal entities choose how they recognize groups by counting them in the census, granting or withholding rights, and deciding whom to police. By making their voices audible and by claiming a social perspective not acknowledged by powerful authorities, rap artists sought not assimilation but recognition.55 Bonnette has pointed out that although urban youth do not have access to the means of political change, music allows them to enter public space as entertainers and then use that media presence as a springboard to political participation.56

African American music became a transnational project with the support of Cold War networks of power. From the 1940s to the 1980s the government of the Soviet Union engaged in intensive propaganda campaigns that publicized the continuing violence against black people in the United States. Worldwide, newspapers published frightful photographs of abuse and described continuing violent conflicts about school desegregation.57 To combat this publicity, the US government sent books, pamphlets, and films about prominent African Americans all over the world. One pamphlet described black Americans’ “constant progress towards full enjoyment of the rights and privileges of free men.”58 Many people abroad took an interest in this drama and felt an imagined connection to African Americans. Pan-African activists cultivated this empathy, encouraging the travel of African American intellectuals to Africa. Both the US and Soviet governments sponsored international travel by African artists and political leaders to their respective countries, as well. In the 1960s postcolonial activists all over the world linked the struggle for African American civil rights to their own struggles for equal rights and self-determination.59

With this engagement as a backdrop, it is not surprising that the emergence of hip-hop in the 1970s sparked a global movement that continues to the present day. The sociologist Sujatha Fernandes has pointed out that Page 221 →although pan-Africanism has motivated some people outside the United States to adopt hip-hop, others find a connection in the genre’s tradition of commenting on urban conditions, especially poverty.60 The performance of this music involves highly animated speech, so it is no surprise that groups whose speech has been marginalized have seized on rap as a way to give voice to their perspectives. As in the tradition of rap in the United States, MCs from other parts of the world offer commentary on particulars of their situations, stating what needs to change.61 Here I take up just a few examples, with an eye toward examining the nature and purposes of this appropriation.

Yugen Blakrok is an MC from South Africa whose work is densely woven and poetic. Blakrok frequently makes reference to images from Afro-futurism, an artistic movement that blends pan-African themes with themes from science fiction, presenting images of alternative future worlds as a means of criticizing the existing world.62 The song “DarkStar,” on Blakrok’s album Return of the Astro-Goth, flits between very brief criticism of social problems and images of flight and cosmic wisdom:

At night-time while the homeless lie awake in insomniac states

I’ve spat on God’s face for the lives he wouldn’t take

Saw we’re suffering for suffering’s sake

Birdbrains stuck wingless in a cage

Hallucinating warped perverted images in the shape of the snake

I have read between the lines of historic fallacies

And now disappear in mists with no chances of you finding me

Turn the pages and learn the end of each age is

Preceded by the most inspired works of the sages

One day I’ll lace a verse in 365 takes

Then launch my sound body into space

Where my food for the soul will be served on a cosmic plate

And occupy minds through invisible sound-waves.63

Blakrok cites Queen Latifah, Public Enemy, and other US musicians of the 1990s as her biggest influences, and her lyrics invoke the socially critical tradition and content of US rap music.64 In particular, the words of “DarkStar” complain of homelessness, entrapment, the “mark of the slave,” and police violence: how “cops know the flows blow holes through bulletproof vests.”

The problems Blakrok describes are not localized: they could be the problems of any city. Blakrok’s appropriation of rap alters the sense of the “local” Page 222 →that was so present in New York hip-hop of the 1980s and 1990s; instead of arguing that the speaker is surviving despite the rigors of a particular neighborhood, the speaker in Blakrok’s song engages in fantastic escapist thoughts—“food for the soul . . . served on a cosmic plate”—that contrast with the social problems she names. The mix of social critique and self-assertion is present here, as it was in Queen Latifah’s rap, but the balance and subject matter have tipped toward a fantastical escape into outer space, in keeping with Afro-futurism.

Blakrok’s style of rapping is remarkable for its rhythmic flexibility. Part of the appeal of the genre is that the rapper’s words pull away from the beat for a while, coming between beats rather than on them, until at last a key word lands on a strong beat. Sometimes Blakrok raps for long stretches before her words coordinate with the underlying pulse. This effect gives her music a breathless and floating feeling that matches the imagery in the song’s music video, in which Blakrok’s face floats through outer space in an old-fashioned television set (example 8.5).

Also remarkable are the aspects of rap that Blakrok adopts selectively. Some women MCs choose suggestive costumes to resemble the female dancers in US rap videos. Blakrok is more likely to be seen in a hoodie sweatshirt and baggy pants, clothing associated with a male MC in the United States. Sometimes she uses costume and special effects to create an otherworldly persona (as in her “House of Ravens” video; see fig. 8.4). One of the standard stories people tell about globalization is that American corporations are wiping out differences, making all the available music more alike. But the sound of Blakrok’s rapping is distinctively her own, as is the visual style of her videos. Blakrok’s performance presents an Afro-futurist vision of modern Africa: she adopts the subject matter of hip-hop selectively to suit her own purposes.65 Hip-hop is not the same all over the world, but individual musicians find power in drawing on the idea of a worldwide community of musicians in solidarity—an imagined community spanning several continents.66 And as Okon Hwang has pointed out in another context, people are not required to Page 223 →regard any repertory as the possession of a particular group or nation. Individuals who appropriate music from elsewhere typically perceive their musical choices as personal, not group, expression.67

In the Arab world MCs have experienced a broad range of responses to their work—from enthusiastic public acceptance to state suppression and exile. At the northwestern edge of Africa, Morocco is a kingdom with a history of authoritarian repression. The monarchy limits free speech, and although citizens may criticize other parts of the government, they may not criticize the king.68 Yet the music of Youssra Oakuf, who raps under the name Soultana, is infused with social critique. As a Muslim teenager who began to get involved in hip-hop in the early 2000s, Soultana risked her reputation by attending the clubs that host hip-hop performances.69 Some Moroccan music fans remain unwilling to accept female rappers, and Soultana’s willingness to speak openly about poverty and prostitution has also troubled her listeners. Nonetheless, Soultana has been prominent on the Casablanca rap scene for more than a decade.

In a rap called “The Voice of Women” from 2010 (example 8.6) Soultana condemned poverty and the harassment of women on the street. The lyrics accuse Muslim men of hypocrisy, saying that they pretend to be devout but also use women as prostitutes and shame them:

You looked at her like she was a cheap thing.

She saw in your face what she wanted to be.

You looked at her, a look of humiliation.

She’s selling her body because you are the buyer.

And when she’s walking by, you act all Muslim.70

Page 224 →Soultana links her motive for getting into hip-hop to the status of women in Morocco: “All I was searching for was not fame or money or something like that—I was searching for respect from people.”71

Soultana delivers “The Voice of Women” in an emphatic and clearly spoken style, making every syllable audible. According to the ethnomusicologist Kendra Salois, this clarity is important, for Soultana’s success has depended on her ability to draw in listeners who are not used to contemporary rap or its fast pace. This mode of delivery is a form of teaching and community building: Soultana frequently explains aspects of the hip-hop tradition or the meanings of specific songs before she performs them and even checks with the audience to make sure they have understood. Addressing her fans, she has said that “the culture of hip-hop is in our blood”—helping the audience to feel part of the transnational tradition of socially conscious hip-hop.72

Much like African American rappers, Soultana uses rap as a means for Moroccans to talk about important issues: poverty, harassment, gender discrimination. Yet there are limits to this criticism: Moroccan MCs may make remarks about “the government,” but they dare not attribute social problems to the king’s poor leadership. Whether or not they disagree with the present ruler, to voice such criticism would be a punishable offense.73 Instead, when talking to the audience from the stage, Soultana and other Moroccan rappers couch their social criticism within the language of personal responsibility. This language is rooted in the Muslim traditions of virtue and citizenship, and MCs make reference to these principles when talking to audiences. As a political strategy, assigning personal responsibility for social problems means that the MCs’ criticism of the status quo does not challenge the state’s leadership. Rather, Salois writes, the focus is “transforming Moroccans into a certain kind of citizen.”74

Since 2010, Western interest in MCs from the Arab world has been fueled in part by a region-wide conversation about personal and artistic freedoms. From late 2010 to mid-2012 popular demonstrations and uprisings took place throughout much of North Africa and the Middle East. Known as the Arab Spring, these demonstrations reflected a variety of forms of discontent. Protesters spoke out against political corruption, income inequality, and resentmentPage 225 → against rule by dictators or monarchs. Many of the demonstrators also demanded more democratic forms of government. The protests sparked a civil war in Syria, and rulers of several countries were forced from power. Even so, only in Tunisia did the demonstrations result in a substantive change in government.

These dramatic circumstances focused Western attention on dissenters. When the Egyptian rapper Mayam Mahmoud appeared on the TV show Arabs Got Talent in 2013, her head covered with a hijab (head scarf), her performance set off a flurry of media interest in Western countries (example 8.7).

Mahmoud’s lyrics, which come from the tradition of Arabic spoken-word poetry as well as from rap, call for women’s freedom. In the song “It’s My Right” Mahmoud’s refrain addresses the men in the audience, assigning them the responsibility for respecting the freedom of women: “Even before it’s my right, my freedom is your duty.” Mahmoud goes still further, outlining the freedoms she claims for women:

I have the right to complete my education until I’m fully satisfied.

I have the right to show myself to the world. I don’t want to disappear.

I have the right to choose my own partner and not my family’s choice

to share the road with me and to help me complete my journey.

I have the right to have my brother respect me and not attack me.

Don’t tell me, “Freedom’s in other countries” or tell me to hush.75

Like Soultana, Mahmoud denounces a great deal of behavior in the everyday context in which she lives, but she is not calling for revolution: she does not claim opposition to society as a whole or to the religious principles by which her society is led. These performances do not criticize Islam; rather, they are based on core Islamic principles.76

By choosing rap as a mode of expression, musicians from the Islamic world become entangled in the international media. Salois observes that Western journalists often ask Muslim hip-hop artists to repudiate Islamic fundamentalism or overemphasize the extent to which they are breaking norms in their countries. To those who are both devout in their faith and calling for particularPage 226 → kinds of change, questions about these topics can seem like a trap: “if a Muslim artist reaches a certain level of visibility, eventually she will be asked to choose a side in a discourse whose terms she can’t control.”77 These artists recognize that they may be misrepresented in stereotypical terms as religious extremists or radical pro-Western reformers—portrayals that do not match the complexity of their daily reality.

Both state policies and global music companies may restrict what speech makes it out into the wider world. As Salois points out, musicians find themselves in a double bind. Although what they want to say may or may not conform to the expectations of the state and the marketplace, in order to have their voices promoted enough to be heard, they must conform to those expectations, at least to some extent.78 The nature of those constraints differs from place to place: they may include censorship of public or mediated performances, limits on what media can circulate in the artist’s environment, and access to sponsorship that would bring the artist into broader public awareness. As the ethnomusicologist Ali Colleen Neff has described it, female rappers in the West African nation-state of Senegal face “an exploitative tourism industry, corruption in the national government, self-serving world music promoters, parasitic European corporate interest in the Senegalese telecommunications, power, and banking industries, [and] persistent prohibitions on women’s divorce and inheritance rights.”79 All artists experience some constraints, and for many the constraints are severe enough to threaten their ability to be heard.

Many MCs from lower-income countries affiliate with foreign music companies to achieve wider publicity and distribution. For example, Yugen Blakrok is represented by the German record label Iapetus. Rap artists outside the United States can gain some attention by their presence on “top 10 artists from [any country] you should hear” lists on the internet, many of which are paid advertisements published by third-party promoters. The marketing of rap music from outside the United States to North Americans resembles the “world beat” phenomenon, which demonstrated a mixture of genuine musical interest and the pursuit of ever more novelties to sell in the marketplace.

If the musicians attract enough attention, recording companies may sponsor professionally made video biographies—short videos that allow the musicians to introduce themselves. Like the performances of national folk-dance troupes, these videos have a fairly standard format. The artist speaks in brief interview segments about personal history and local circumstances. That footage is interspersed with performance video, which often appears to be filmed Page 227 →in the artist’s neighborhood of origin, aiming to demonstrate some special qualities of that scene. This sense of being local is tactical: as the literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt points out, art that seems to be original or rooted in place may attract special attention because it seems authentic.80 At the same time, these videos explain the artist’s personality in a way that engages Western audiences. In a promotional video that explains her music to an English-speaking audience, for example, Soultana explained: “Hip hop taught me how to be strong, how to face men”—emphasizing the feminist aspect of her Moroccan rap that may appeal to women in the West.81 To make a connection, statements like these may gloss over the strategic differences between Soultana’s self-presentation and that of Western artists.

Thus, many musicians adapt their music and their self-presentation to make their music marketable. Is this adaptation a threat to other musical practices? Possibly so, for as musicians accommodate themselves to the demands of the marketplace, they may choose some traditions and abandon others. As Appiah has pointed out, though, each musician should have the right to decide what kind of music to make: “telling other people what they ought to value in their own traditions” is neither productive nor appropriate.82 Canclini also notes that global corporations can coerce or limit artists because they cater so much to the desires of people in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Cooperation with music distributors may also place artists into exploitative financial relationships.83 Artists may or may not resent these trade-offs. Abdoulaye Niang, who has worked for the United Nations Economic Commission in West Africa, has explained that the Senegalese MCs he knows want to represent their “specific cultural and social aspirations” while participating in larger systems.84 Yet the initiative to decide on the pros and cons of participation must remain with the individual musician. Indeed, the power to mix musics also means the power to decide how one is represented to the world. According to Canclini, blending traditions can free musicians from feeling obligated to represent a single traditional identity, allowing them to express new or mixed identities that better reflect the particulars of their situations.85

Examining these extensions of the rap tradition, we might ask with Canclini: what world are these artists entering (or creating), and what are they leaving behind? The adoption of rap by people outside the United States allows them to enter a global music marketplace, as well as regional and international conversations about social concerns. This borrowing grows not from a desire to take others’ music but rather from a sense of affinity and shared experience. At the same time, many MCs from outside North America do not Page 228 →talk about their musical style as borrowed: they recognize the roots of rap in the United States, but they understand their music as their own creation. Like the later generation of mediated selves discussed in chapter 6, the MCs discussed here have a great variety of musical styles and techniques at their disposal; their art feels like an integrated and novel whole, not like a mere borrowing or copy. The Moroccan and Egyptian rappers discussed here have not left their own sense of self behind; rather, they have made music to represent themselves, defining their own places in the world.86

The anthropologists John Kelly and Martha Kaplan have argued that people need representation in two senses: metaphorical representation, having the feeling of being heard, seen, or recognized; and literal representation, as in a democracy that grants and protects their rights.87 Artists who create blended musics engage in metaphorical representation, ensuring that they can be recognized as they wish. If we look only from the perspective of the “world system” or the other large-scale systems in which artists live, we might not recognize the individuality of their contributions or the meaningfulness of their music to them personally: their mixing of musics may look like the product of global forces. If we listen closely to the artists, however, we can hear them; they exert individual creativity to shape the music around them, and they purposefully add their voices to a broader conversation about how the world should be.