3.2: Composing the Mediated Self

- Page ID

- 172101

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

The Canadian communications scholar Marshall McLuhan wrote in 1964 that because of media, “the globe is no more than a village.” He believed that the media were creating a worldwide sense of involvement in others’ lives, even over vast distances. Where people formerly might have associated only with people from their immediate communities, television brought into homes the images and voices of unfamiliar people, as well as their music and art. McLuhan called the media “extensions of man,” as if they wired our nervous systems to a network, making our eyes and ears reach further than they ever could before. Having to pay attention to all that input could overwhelm people, but it could also make them feel a new “interdependence with the rest of human society.” These extensions created an uncanny intimacy, even with faraway people: “Everybody in the world has to live in the utmost proximity created by our electric involvement in one another’s lives.” The “global village” is now a cliché, but McLuhan was one of the first to describe how communications media might be changing human social life.1

Would that process of becoming connected “make of the entire globe, and of the human family, a single consciousness?” McLuhan expected that peoples would become more similar as a result of this connectedness and especially that the less powerful would feel pressure to conform. Part of his concern was that the media was already an industry: having rented out our nerve endings to corporations, we are now subject to the input those corporations choose.2 Even as McLuhan thought about profound changes in African and Asian lives, he also believed that global connectedness was “de-Westernizing” people in Europe and North America.

This intuition corresponds to some of what we already know about how music moves. As we saw in chapter 4, the nature of sound recording and the distribution of those recordings changed a great deal during the 20th century. The Cold War years saw the development of new kinds of media, and individuals and nation-states created new reasons to move music across borders, both Page 152 →personal and political. If we take McLuhan’s ideas seriously, we must consider the possibility that this transformation also made a change in people themselves: in how they think and behave and in their preferences and opinions.

Writing in the 2000s, the anthropologist Thomas de Zengotita tested McLuhan’s theories by observing present-day behavior. De Zengotita’s theory of mediation suggests that people who live in a “mediated” way are indeed different from their “less mediated” forebears.3 Of course, experiences have been mediated by newspapers and books since the invention of printing with movable type (in China around the year 1040; in Europe in the 1420s). The history of mediation goes back much further if we count the circulation of ideas in oral or handwritten forms. Still, de Zengotita and McLuhan argue that with television and other 20th- and 21st-century mass media, we encounter a more complete transformation of what it means to be a person. Here are some of de Zengotita’s key ideas about how mediation affects our experiences.

Being the recipient of media changes people by sheer flattery. You are constantly addressed, your attention requested, your tastes complimented. Information you want is brought directly to you, hundreds or thousands of times a day, by advertising and other media. All this information seems to be addressed to you, personally. De Zengotita calls the result of this kind of mediation the flattered self. He claims that the flattered self has a kind of god’s-eye view—everything that person might wish is all available, all the time.4 When a person goes looking for some music (say, the examples of Chinese rock music discussed in this book) and for some reason cannot find that music quickly on the internet, it is easy to become annoyed and feel personally thwarted. We have developed expectations that we will be able to get whatever we’re looking for, with only modest effort. That effect is the god’s-eye view. Of course, not everything is equally accessible—it is the appearance and expectation of total accessibility that defines the worldview of the mediated person.

This appearance of accessibility is grounded in real experiences. We saw in chapter 4 that audio recordings helped make music more accessible: with the introduction of long-playing records in 1948 that trend continued to accelerate. Moreover, in the 1960s air travel became affordable for the first time. It became possible for ordinary people to go somewhere very far away just because it seemed interesting. This kind of travel differs radically from permanent, one-time migrations, in which people frequently have no choice about where to go or whom to interact with. Rather, with all this choice some individuals began to experience culture as a kind of buffet: a musician could sample the music of the world through recordings and travel, borrowing at will.

Page 153 →Another part of being a flattered self is thinking that one’s own opinion should be heard by the world. This effect manifests itself in social media, where people broadcast their opinions and activities publicly, and on television shows in which many people, no matter how badly they sing, have a chance to be heard and judged by millions of listeners. The people who feel directly spoken to by media, and those who always feel free to offer their opinions or judgments in return, are flattered selves. As we will see, many musicians of the generation that came of age between the 1940s and the 1960s believed they had something urgent to communicate through their music: they aimed not merely to entertain or engage their listeners but also to use music as a particular kind of expression that was both personal and political.5

According to de Zengotita, the fact that music or food can represent social class or ethnic origin is not unusual. The era of mediation brought a heightened awareness of that representation and frequent opportunities to represent themselves to the world in self-conscious and carefully chosen ways. Heritage, all that is passed down within a family or ethnic group through the generations, still plays a significant role for most people. But the mediated person need not continue in the musical tradition she has inherited. With the increased accessibility of music through a variety of media, and the dazzling array of options for representing oneself, the flattered self makes choices about how she wishes to make music and how she wants to be perceived.

In the discussion of African American traditions (chapter 3) we saw that some thinkers used the idea of authenticity to emphasize and reify heritage, drawing distinctions between groups of people. This concept of authenticity derived from the purposeful social distinction that separated “folk” from “modern” peoples and presumed a stable connection among people, their habits, and a particular place (“These are real Swedish meatballs”; “This is a genuine Appalachian folk song”). In the case of the African American concert spirituals in the Harlem Renaissance, intellectuals argued about whether concert spirituals were “authentic”—that is, whether a musical practice that showed signs of assimilation truly represented African American heritage or a watered-down, false version of that heritage. Once we are aware of choices and of mediation, the idea of authenticity may lose some of its force. Today, some people would take the perspective that both kinds of performance are valid options—that individuals may choose how to represent themselves through music. This is a highly mediated way of looking at the world. Others might defend the “realness” of boundaries and insist that we can tell true from false, authentic from inauthentic. I will return to these perspectives in my conclusion.6

Page 154 →The identification of styles, habits, or artifacts with a particular ethnic origin, social class, or political issue continues to operate very strongly for mediated people, in that people who feel invested in a certain ethnic group or political issue choose certain styles of music that they think represent them and their cause. But again, this is a choice of representation. The link between the music and other aspects of social identity is not automatic or given at birth, nor does it appear to be limited by geography, nationality, or similar factors. Each mediated individual gets to choose for themselves out of a whole world of available possibilities. Choices about how to present oneself have existed for a very long time, but the vast array of choices and the sense that one is continuously broadcasting those choices seem characteristic of our historical moment.

De Zengotita points out that deciding whether mediation is good or bad is extremely difficult, because the exact same forces contribute to both the good and the bad aspects. The same global, multinational record companies that enable greater access to diverse cultures may also be accused of causing market pressures that crush the initiatives of small record labels in low-income countries. The borrowing of music may create a meaningful positive relationship, or feel like theft, or both at the same time.7

De Zengotita is well aware of the fundamental inequity in the world situation that allows some of us to be flattered, mediated selves, while some of us have little or no access to such options and choices. In his terms you have to live in the “real” world all the time if you have no access to the options and choices presented by the “mediated” world. Some people do not have financial resources that enable choice. Some people live under political or military duress and are forced to do things a certain way. Some people are just not tied into the global economy through media, and they might not have access to options. Because the rest of the situation of mediation is ethically murky—it is often hard to decide what is better or worse—the inequity of access seems to be the main aspect of mediation that can be criticized in ethical terms.8

The examples considered in this chapter connect de Zengotita’s and McLuhan’s theories of mediation with the politics of musical style established during the Cold War. The political pressures that people experienced during that period and the new availability of music through various media combined to shape musicians’ choices. Through recordings and travel US musicians working in the 1960s and thereafter had access to a wide variety of music (providing them with a god’s-eye view of world music). They could choose among a vast Page 155 →array of musical styles, and appropriate one or several of those styles. Crucially, they based their choices on social, political, and ethical considerations—some to assert a sense of connection, some to highlight their personal criticism of the world around them. In all these ways these musicians seem to be the first generation of music-makers to carry the new “mediated” attitude that de Zengotita describes. We will also encounter some US musicians—most of them younger—who, in their own ways, absorbed and extended the lessons of the “mediated generation.”9

Paul Simon: Musical Appropriation and the Mediated Self

First, we should establish how the mediated self thinks about and appropriates music. The making of Paul Simon’s album Graceland offers useful insight. Simon (1941–) made the album with extensive cooperation from the South African musical group Ladysmith Black Mambazo, whom he first heard on a cassette tape around 1984. It was inconvenient that the musicians were South African: the United Nations (UN) had placed that country under international sanctions because of the South African government’s segregation of people by racial categories (apartheid), its massacres of black Africans and other people of color, and its arbitrary detentions of protesters.10

The United States abstained from the UN’s resolution until 1986, so, as a US citizen, Simon could legally travel to South Africa.11 At the same time, many other countries had suspended musicians’ travel to South Africa. Simon went, but his breaking of the UN boycott drew heated criticism. In response to these accusations Simon said that he was supporting black South Africans, paying them triple what they would receive in the United States, and giving them an international outlet and visibility. The UN Anti-Apartheid Committee looked into the case and decided that Simon did not violate the spirit of the boycott since he had not supported the South African government in any direct way.

Simon had a point. Because Graceland was such a huge hit, it transformed the careers of the African musicians involved. The South African group Ladysmith Black Mambazo had been recording since the 1960s and had been on the radio in Africa. After they recorded with Simon, they became international celebrities. The group’s bass player, Bakithi Kumalo (1956–), defended Simon’s relationship with the African musicians:

Page 156 →Bakithi has little patience with critics who brand Simon a cultural plunderer or musical imperialist. “Well, I’ve been asked this question many times, even by my own people. To be honest, I don’t see anything wrong.” He says thoughtfully, “I tell people, ‘Listen, this is my life. I’m a musician. Whoever calls me and says, hey, let’s play South African music’—why not? Because that pays my bills, you know, that takes care of me! . . . I don’t see any problem with Paul learning and getting involved with South African music. If he didn’t do it, I don’t think anybody else would!”12

Even many years later, everyone involved with the recording remains sensitive about the ethical issues that the project raised.

Simon was also an attentive listener. The ethnomusicologist Louise Meintjes has pointed out that Graceland skillfully includes characteristic elements of South African music. The distinctive sound of mbube, choral singing that juxtaposes a chorus of low voices against a high lead singer, is evident throughout much of the album. Example 6.1, “Wimoweh,” sung by Solomon Linda’s Original Evening Birds in 1939, exemplifies the characteristic texture of mbube.

Simon’s song “Homeless,” in example 6.2, offers a similar sound: low voices singing in harmony and a high voice soaring above.

Simon’s album also draws on the South African genre of mbaqanga, or township jive. (The q in mbaqanga is pronounced as a tongue-click.) According to Meintjes this music recalls mbaqanga both in the choice of instruments—especially the electric bass—and the way the instruments engage in interplay with the voices.13 The song “Akabongi” (example 6.3), sung by the Soul Brothers in 1983, illustrates some key features of mbaqanga.

Page 157 →

The solo guitar is prominent at the beginning of the song, with a playful little “warming up” tune. Once the drums come in and the groove starts, we hear the bass guitar as a driving force. Voices singing in harmony alternate with a small group of backup instruments. Simon’s song “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” features similar strategies. Although the song begins with a slow introduction in the style of mbube, about a minute into the song (at the start of example 6.4) we hear a brief guitar solo, much like the one that started the Soul Brothers’ song.

Almost immediately the groove starts, with a prominent part for the bass guitar. Unlike the Soul Brothers, Simon sings the verses alone, but like them, he includes interludes by a small group of backup instruments (example 6.5). Later in the song, we hear a chorus, singing in harmony on the syllables “ta na na na” in a way that recalls mbaqanga.

Simon has emphasized in liner notes and interviews that the musicians worked collaboratively to create Graceland. Still, a video about the making of the album includes a revealing moment. Seated at the mixing board, Simon shows how he created a demo recording of the song “Homeless,” overdubbing his own voice several times to create the harmony he had in mind for the chorus of the song. “It’s all me,” he says (fig. 6.1).14 The video goes on to describe how Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo changed the harmony together, but the concept of the song was evidently Simon’s.

At another moment in the video Simon demonstrates how the characteristic sound of the album was created through mixing, blending his own ideas with the sounds composed by the South African musicians. Discussing the song “Boy in the Bubble,” Simon explains that, to his ears, the drum at the start of the song sounds “so African.” But he then demonstrates at the mixing board how he altered the soundscape to conform to his own idea of what “Africa” sounds like. He recorded the characteristic sounds of the accordion Page 158 →and the prominent bass guitar line but added synthesizer, bells, more drums, and multiple tracks of his own voice in the background. Again, it’s “all him.”15

At the mixing board we could say that Simon is a flattered self with a god’s-eye view of all the available sounds. He can make each one louder or softer; he gets to choose the final mix. He occupies a highly empowered position. That power comes both from the technology—he is the one who has access to the mixing board—and from his position in the web of social relationships. He pays the other musicians, so he gains the right to manipulate their sounds as “raw material” and make choices about the final product.

Does this borrowing differ from Liszt’s adoption of the Romungro style (chapter 2)? In that case Liszt tried to adopt or imitate the essential features of Romani music in order to make his own music seem livelier and full of passion. He found their lifestyle and their music exotic (charming because unfamiliar). So far, the cases seem similar: Simon, too, was charmed by the sound of South African music, which was novel to him, and he wanted to incorporate that sound into his own music. Yet Simon’s technology of imitation is quite different. He has a mixing board: he can take ownership of other peoples’ sounds and blend them with his own. In some ways the resulting imitation is seamless: it is difficult to tell whose ideas are whose.

The ethnomusicologist Veit Erlmann has complained about this aspect of Simon’s music. He called the “seamless” quality an offensive form of cultural appropriation. In Erlmann’s view Simon created an inauthentic facsimile of African music, as if Simon had a hand puppet of Ladysmith Black Mambazo and was telling it what to say and how to be “African.” Erlmann saw this projectPage 159 → as selfish: Simon was the center of his own universe, and he took for his own purposes everything that could be foreign, absorbing it all into his own music. In other words Erlmann saw Simon’s flattered self as a serious problem: Simon was so invested in his god’s-eye view that he failed to understand the other musicians’ perspectives.16

But the musicians involved in making Graceland have stated in no uncertain terms that they were delighted to work with Simon, that they found the process worthwhile, and that they appreciated the musical and economic opportunities the collaboration brought them. Though Louise Meintjes rightly pointed out that the songwriting contributions of South African musicians are credited inconsistently and sometimes downplayed on the album, guitarist Ray Phiri insisted that “there was no abuse.”17 The positive and negative elements of this collaboration are difficult to untangle.

The question of borrowing between the United States and other countries calls to mind all the questions of inequality raised in studies of colonialism and globalization. Economic barriers make it difficult for even well-intentioned individuals to meet on equal terms. McLuhan wrote that the existence of any kind of frontier between unequal societies stimulates frantic activity on the part of the “less developed” side, creating in them the desire to catch up or modernize.18 Yet as we saw in chapter 5, during the Cold War the need for alliances also prompted frantic activity on the part of superpower nation-states as they attempted to win over nonaligned peoples throughout the world. Simon’s interest in traveling to collaborate with South African musicians echoes this push to make connections; it also reflects the interest of Ladysmith Black Mambazo in “catching up” by gaining access to international audiences. Economic and political boundaries generate excitement in part because the stimulus for connection creates multifaceted meanings on all sides.

The Paul Simon case shows that mediation not only connects people but also reinforces the noticeable inequality between those who can mediate their experiences at the mixing board and those whose music is appropriated as raw material. We might recall here the discussion of cultural appropriation in chapter 3, which highlighted unequal credit and earnings. Simon’s music and the concerns that come with it are characteristic of the 1980s, when world beat (sometimes called world music) became a category for record sales. The Graceland album’s great success was not an isolated incident: the phenomenon of Western musicians promoting or appropriating music from elsewhere was common (as we saw in chapter 4).19

This question of creative control shapes how we interpret what is going on. Page 160 →McLuhan saw the mediated self from the receiving end: the mediated person is part of the “masses” who effectively rent out their nerves and senses to the media industry but may not make their own art. For people who have access to and control over the distribution technology, though, the mediation process looks vastly different. Think again about Paul Simon at the mixing board: recording technology makes us aware of other people’s music (in his case South African music) in a way that may encompass ownership (of a recording), desire to participate (through travel), collaborative interaction (making a recording together), and creative control (at the mixing board). All these activities offer plenty of space for musical inventiveness. That empowered sense of creativity is characteristic of the mediated self.

A Mediated Generation: Representing Oneself through Chosen Styles

Many members of the generation that came of age in the 1950s and 1960s believed that the Euro-American (or “Western”) tradition of concert music—often called “classical” music—was too rigid: they chose to blend a variety of ideas and sounds from outside that tradition into their music. The music of Terry Riley (1935–) offers another case of purposeful borrowing; unlike Simon’s, Riley’s borrowing involves an imitation of style rather than a direct incorporation of sounds. Riley is from California, a virtuoso pianist and composer. In his youth he was influenced by serial music (like Pierre Boulez’s Structures Ia, discussed in chapter 5), but he then turned away from that technique. Far from wanting to separate his music from the conventional meanings of daily life, Riley wanted to transform life through music. He has referred to his own music as “psychedelic cosmic opera,” an “expansive experience.”20

From 1970 on, Riley immersed himself in the study of North Indian (Hindustani) classical music.21 Music from this tradition typically unfolds as a long, gradual process, starting at a low pitch and moving slowly, then increasing in intensity and speed and encompassing higher pitches in the musical scale. This process may last several hours: the listener’s satisfaction comes from paying attention to the music’s revelations over time.

North Indian music typically includes a drone: a note that is held steady over a relatively long time. In example 6.6 we hear a drone starting at the very beginning of the track.

Playing above that drone, we hear instruments called shahnai (a double-reed instrument, like an oboe). These instruments are frequently played in pairs: the melodies of the two intertwine with or echo each other more and more as the piece goes on. Soon a pair of drums, called tabla, joins in, increasing the energy and giving the music a more steady rhythmic pulse. If you listen for a while, you will notice the melody getting more expansive and the energy and complexity of the music increasing over time.

In 1976 Riley composed a piece that imitates this kind of music, entitled “Across the Lake of the Ancient World.” A drone is present in some parts of this piece (we hear the opening in example 6.7) but not as consistently as it would be in North Indian music; sometimes it goes away for a while, then returns.

Instead of using reed instruments (the shahnai), Riley chose a Yamaha electric organ, which has a similar reedy tone. But Riley’s most essential borrowing for this piece is the Hindustani practice of increasing complexity and rhythmic interest as the music goes on through time. Riley crafted a gradual introduction of material that offers a satisfying sense of expansion. As “Across the Lake of the Ancient World” goes along, the music becomes more rhythmically active, and the melodic lines become more intertwined with one another, much like the trajectory of Riley’s Hindustani models. Example 6.8 includes a short selection from the middle of the piece, a pause, and then a selection closer to the end.

As would be true in the Indian tradition, this music has improvisatory elements: the listener has a sense that every performance is unique, not repeatable.22

Page 162 →Riley, who was not born into the North Indian musical tradition, chose this musical practice specifically as an alternative to the Euro-American classical tradition. His attraction to Hindustani music was founded in part on ideas about how society should be different: when he rejected the serialism of the 1950s, Riley sought an alternative to Western music that would provide a sense of countercultural mysticism. The musical process that gradually unfolds engages the listener in a process of transformation—even an expansion of consciousness—that seemed utterly different from what Western concert music could offer. Riley’s choice represented a commitment to transformative listening of this kind. To Riley, and to his listeners, this choice also made a statement: non-Western ways of being might affect us in ways that our own Western practices and values cannot. Riley did not assimilate into Hindustani ways of life; rather, his musical borrowing exemplifies admiration for Hindustani music, as well as a desire to replicate its effects, both musically and spiritually.

Like Riley, Lou Harrison (1917–2003) sought alternatives to his Western training. Harrison studied composition with Henry Cowell, who was important both for his radical socialist politics and his interest in all kinds of music. Harrison lived in San Francisco, California, for much of his life. There, on the Pacific Rim, Asian influences were much more prevalent than elsewhere in the United States. San Francisco has a large Chinese community, and Harrison encouraged his students to hear Chinese opera there. Along with Cowell, Harrison was a very early advocate of pacifism and multiculturalism (even in the 1930s, before multiculturalism had been named). Harrison spent time in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in the early 1960s; he also studied with Indonesian musicians in the 1970s and visited Indonesia in the 1980s.23 These were not fleeting interests but long-standing and serious ones. With his partner, William Colvig, Harrison constructed two sets of gamelan instruments, now located at San José State University and Mills College.

Harrison idealized what he called “Pacifica” (Asian/Californian culture) as opposed to “Atlantica” (East Coast/European culture). He persistently referred to Europe as “Northwest Asia,” trying to marginalize Europe’s importance in favor of other places. Harrison consciously intended to disrupt or overturn the established hierarchy that gave special status to European music: he wanted to create a level playing field where all music could be equally valued and used by whoever wanted to use it.24 Harrison presented a musical model of Pacifica by adopting many features of Asian music in his own compositions. Even before his first trip to Asia, he began borrowing ideas from Asian music, adding the pentatonic (five-note) musical scale and bell-like sounds to his compositions. Page 163 →Spending several months in Korea and 20 days in Taiwan, he learned to play several instruments: the Korean p’iri and the Chinese guan (both wind instruments with a reedy sound) and the Chinese sheng (mouth organ), zheng (a stringed instrument, like a lute), and dizi (flute).25

Among his many musical influences Harrison deliberately included Chinese traditional music. In the Cold War United States this was a pointed political gesture. With communist China considered a major threat to American security and proxy wars with the Chinese taking place in Korea and Vietnam, to claim Chinese culture as a peaceful alternative to US-style politics was profoundly countercultural. Harrison’s composition Pacifika Rondo (1963) made such a claim: this multimovement piece protested against American military action and the atom bomb, imitating musical styles from all around the Pacific basin as a sign of solidarity with Asian peoples. Harrison used the serial technique and an imitation of a military band to represent the harshness of the US nuclear attack on Hiroshima, Japan. With musical styles standing in for peoples and their actions, this choice seemed like a claim of allegiance to Asian values and a condemnation of Western values.26

In Harrison’s “Music for Violin and Various Instruments” (composed in 1967, revised in 1969) he combined the Western violin with an ensemble of instruments from other parts of the world: a reed organ (based on the Chinese sheng), percussion, psaltery (a harp-like instrument based on the Chinese zheng), and four mbiras (thumb pianos), an instrument developed by the Shona people of Zimbabwe. Rather than just borrowing the instruments, Harrison often built his own copies of them. Remaking the instruments allowed Harrison to tune them according to his personal musical preferences; the retuning also allowed instruments from a variety of origins to sound good together.

In the third movement of “Music for Violin and Various Instruments” (example 6.9) we hear the mbiras (thumb pianos) prominently. The first mbira player plays many of the same notes as the violin, while also tapping on the instrument with his fingers and stomping on the floor: these techniques make the piece sound a little less like concert music and more like folk music. The tune is vaguely Asian in style; it uses a pentatonic scale, which has often been used in Western music to mark “Asian-ness.”27 The entire movement consists of variations on a short phrase. In some variations arching extensions of the phrase grow more intricate and ornamental; in others lively syncopation is added, making the music more dance-like. The movement has a clear overall structure that includes repeated sections; this is a feature retained from Western classical music.

Harrison’s blending of elements makes this music a representative of no one tradition: it is an effort to combine beautiful sounds from different traditions, making what Harrison called “planetary music.”28

Harrison has been criticized for borrowing only the distinctive sounds from non-Western musics: he typically did not borrow overall organizational plans. Even the sounds were altered in the process of borrowing, as Harrison rebuilt the instruments. Harrison did not seek to transform his listeners’ consciousness by asking them to hear music in unaccustomed ways, as Riley did. Rather, Harrison organized sounds within the musical structures typical of Western art music and within the social structure of the Western concert setting.29 Much like Claude Debussy, Harrison expected his listeners to rejoice in the new sounds and in the sense of affiliation with foreign peoples those sounds brought with them. By borrowing sounds, Harrison was not trying to recreate other kinds of music faithfully; indeed, his music includes elements that would not otherwise have been heard side by side. Yet the way he used these sounds from afar purposefully evokes a sense of “foreignness,” reminding the listener that other worlds and ways of being are possible.

We might think of Harrison’s strategy as trying to use positive elements of exoticism without the negative ones. The historian Christina Klein has described Americans’ fascination with Asia in the 1950s and 1960s. US involvement in Asia during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War ensured that the idea of Asia was ever-present for Americans, not only in the news but also in popular culture. Musicals such as The King and I and South Pacific presented stereotypical clashes of Asian and Western characters who seemed irredeemably different from one another.30 But Americans who wanted to criticize US military actions in Asia found in Asian music an appealing resource for expressing solidarity with Asian people. By adopting elements of Asian musics as their own, Riley and Harrison made personal statements reflecting this political commitment.

In the music of Olly Wilson (1937–2018) we can hear a complex working-out of self-definition with respect to multiple musical traditions. Wilson, a scholar and a composer, held a PhD in music composition. He spent a year in West Africa in the early 1970s, and he wrote articles analyzing similarities Page 165 →between the music of West Africa and that of African Americans. As an African American who belonged to the generation after the Harlem Renaissance, Wilson chose to connect to the African American tradition and to consider what about his American life has any connection with Africa. Like many members of his generation Wilson was particularly inspired by pan-Africanism—the idea that Africans and members of the African diaspora share a common heritage.

In 1976 Wilson composed a piece called Sometimes for a singer and tape: the tape contains electronic noises and voices. This piece is based on the concert spiritual “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child,” which we heard in example 3.9. In Sometimes Wilson manipulates the spiritual in various ways. Sometimes we hear fragments of its tune, sometimes entire recognizable phrases; these phrases are sung by the vocalist or appear on the tape as echoes. Meanwhile, the inclusion of noises and distorted sounds on the tape creates a neutral, severe landscape, much like the strange sounds heard in old science fiction movies (example 6.10, timepoint 1:40–3:24).

In some parts of Sometimes (like example 6.10 at timepoint 5:10–6:55) the music sounds like multiple voices speaking or singing at once, which is analogous to the traditional congregational singing of spirituals. The voices on the tape, however, also sound ghostly, distant and disembodied, and the singer’s part disintegrates into howls and other nonverbal sounds. The words “I feel like a motherless child” are reflected in the anguished distortions of the singing voice and the sense that the voice is alone in a hostile environment. By referring to the spiritual and being performed in this particular way, Sometimes calls forth the traumatic history of African Americans in the United States.

In another passage (example 6.10, timepoint 11:20–12:58) the word mother is broken up into syllables and played with, more for the sound and rhythm of the syllables than for their meaning. This musical strategy resembles the jazz tradition of “scat,” where the singer plays with sound and meaning. But, again, it is also a way to make the spiritual a less coherent song, for at this point the spiritual has been torn to shreds.

Wilson was educated in the serial tradition and in what is broadly called New Music—the extension of the Euro-American “classical” tradition into Page 166 →experimental or tradition-breaking practices. (Boulez’s music, discussed in chapter 5, belongs to this genre.) While some practitioners of New Music attempted to deny “meaning” in music, preferring to think of music as abstract sound, Wilson deliberately used the academic language of electronic music to create meaning: “I attempted to recreate within my own musical language not only the profound expression of human hopelessness and desolation that characterizes the traditional spiritual, but also simultaneously on another level, a reaction to that desolation that transcends hopelessness.”31

There is an interesting irony about Wilson’s choice of musical styles. Wilson was trained in the modern postwar musical style represented by tape manipulation—it was his tradition by virtue of his education—yet he also recognized that style as potentially alienating to listeners. So he juxtaposed that style against the voice that sings the spiritual—which was also his tradition, by heritage and by choice—and makes the spiritual sound like the only human voice within an alien landscape. In thinking about his place between the two traditions, Wilson often quoted the African American sociologist W. E. B. DuBois: “One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”32 Although Wilson acknowledged the descriptive value of DuBois’s idea of doubleness, he also said that musical practices constantly adapt or blend to accommodate new situations: “As an individual living at the end of the twentieth century, I have inherited a rich legacy of musical practices from throughout the world, and I have reveled in all of it.”33

Even though Sometimes is concert music in the Euro-American tradition, it also draws on aspects of African and African American music that Wilson defined in his research. Apart from making direct reference to the spiritual, it also embodies what Wilson called a heterogeneous sound ideal; that is, it includes many dissimilar textures, voice qualities, and layers of sound. Wilson identified this heterogeneity as a key feature of African diasporic musics.34 Whereas this sound ideal is most characteristically heard in the nonblending sounds of Duke Ellington’s jazz orchestra or the varying vocal tones of a blues singer, the use of voice and electronic sounds is an extreme version of the same principle. Setting many different sound qualities into contrast with each other helps bring out the human drama of the spiritual in a new way. The combination of styles Wilson uses is profoundly personal, reflecting his own array of social and musical commitments.

In sum, the first-generation mediated musicians discussed thus far—Simon,Page 167 → Riley, Harrison, and Wilson—exemplify de Zengotita’s vision of what it means to live in a mediated age. It is easy to see that they worked from a god’s-eye view: they took advantage of their access to an enormous variety of music not only through historical and present-day sound recordings but also through travel. They could reach outside the limits of their education or upbringing to ally themselves with many kinds of music. As Harrison put it, “I always used just what I wanted when I wanted it or needed it.”35

Second, these musicians made self-conscious musical choices based on political values or social affiliations. By choosing a tradition to use, they also adopted at least some of that tradition’s connotations and used those connotations as a form of branding. Wilson made a personal statement from an African American perspective that also used the resources of concert music. Harrison and Riley were trying to introduce Eastern practices as an alternative to Euro-American culture. Riley also wanted to encourage alternative listening practices. Trained to extend the classical music tradition, they tried to modify the system of musical values they had inherited by adding new sounds from other traditions. The sense of difference that they hoped to create depended on the music’s political and social connotations, as well as on the novelty of the sounds themselves.

Third, these first-generation musicians believed that their musical choices made meaningful public statements. We see them as individuals communicating with the world or commenting on it; they had a sense that their own opinions were important and worth conveying to the world. They were willing to bend or break the conventions and boundaries of their inherited musical traditions to serve their individual tastes and convey their political messages. This sense of self-importance seems to parallel what de Zengotita calls the flattered self, the self of the mediated era that always wants to tell the world what it thinks.

Introducing elements from outside the concert music tradition allowed these composers to present novelties to their audiences. For those who were associated with New Music, novelty was essential; for Simon, too, it served as a selling point. Nonetheless, as much as these composers were motivated by an element of self-interest—taking whatever one wants—they also pushed North American listeners to broaden their definition of “respectable” music. Music’s meaning reflects social conventions: that is, a community’s shared expectations of what constitutes good music. By identifying themselves with musics of Asians, Africans, and African Americans, Riley, Harrison, Wilson, and Simon asked listeners who were used to Euro-AmericanPage 168 → concert music to take these musics seriously—presenting them not as lesser “others” to Western concert music but as peer musics worthy of interest.36 This worldview resembled the United Nations’ vision of a community of nations in dialogue with one another—except that the UN’s vision did not include the mixing of the traditions.

Amid the larger dramas of the Cold War and the civil rights movement, these composers’ musical statements also seemed political. By rejecting or modifying elements of their training in elite forms of Western music, they declined an alliance with the United States as a superpower, allying themselves instead with peoples who were marginalized, some of whom called themselves nonaligned or even enemies of the United States. Musical borrowing and mixing sometimes served as a way for musicians to define a sense of individuality and commitment in relation to a social context where musical style was already political. Given the available definitions of what a musician should be and do, these musicians rejected those definitions and created new ones that fit the stories they wanted to tell about themselves and their world. This, too, is a mediated selfhood—not necessarily a bad one. Being able to define oneself musically offered musicians meaningful opportunities for social and political participation.37

Next-Generation Mediated Selves: Benary, Srinivasan, Bryan

Musicians who came along after Riley, Harrison, and Wilson have mixed musics more and more flexibly, often blurring the boundaries so much that the listener can no longer distinguish what has been blended with what. Barbara Benary (1946–2019), a generation younger than Harrison, developed a particular fascination for the gamelan. A composer, performer, and ethnomusicologist, she studied gamelan as a college student; she then spent time studying violin in Madras, India. On her return to New York she played the violin with the Philip Glass Ensemble, which was experimenting with music based on repetition. As a young professor at Rutgers University she taught traditional gamelan performance to her students; at the same time, she was a member of the experimental music scene in New York, playing with a group called “New Music New York.”

Benary also founded a gamelan in New York, called Gamelan Son of Lion. (The name Benary means “Son of Lion” in Hebrew, so the gamelan was marked as her own; indeed, she built and tuned it herself, with Harrison’s Page 169 →work as inspiration.) She left Rutgers in 1980 and moved to New York, composing and working with the gamelan full time. In her compositions Benary aimed for a loose mingling of musics in which neither is required to accommodate the other or, in Benary’s own words, “a marriage in which neither partner is asked to convert.”38

Gamelan Son of Lion does not perform traditional gamelan repertory from Indonesia; rather, the ensemble has served as a workshop for performances of newly composed music. Whereas in Harrison’s music it seems critical that the listener recognize the “foreign” sources, in much of Benary’s music the Asian origin of the instruments seems almost incidental. This approach was controversial within Benary’s circle of musician friends: some disapproved of using the traditional instruments of the gamelan “as a set of sound producing objects” without pointing to the Indonesian tradition.39

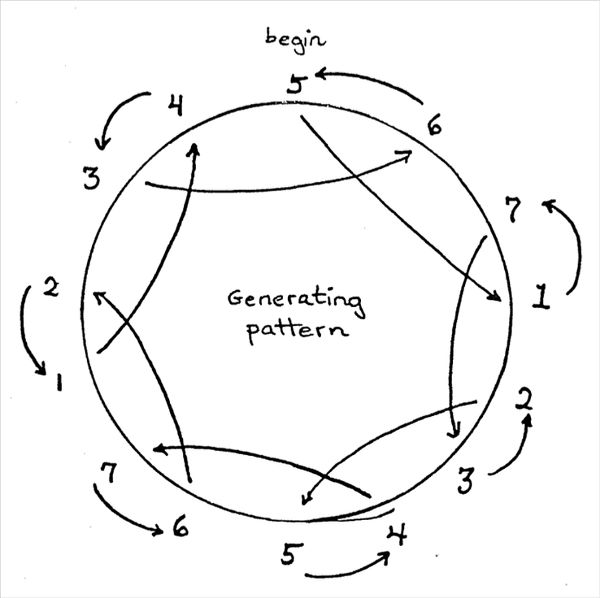

A piece called Braid, which Benary composed in the 1970s, is organized around the repetition of a fixed series of notes that covers all the available notes in the gamelan’s scale (called pelog). In that regard the concept is like that of the serial music of the 1950s, mentioned in chapter 5.40 Benary designed the series like this: from the starting point go three notes up the scale, then one note lower; following this cycle, the player ends up back at the starting point (fig. 6.2). Players move through the piece by repeating the first two notes of the pattern over and over, then (whenever they like) dropping the first note and repeating the second and third notes over and over, and so on. The three parts are offset from each other in time, so they sound “interlocking”—but the organization of the piece has otherwise nothing to do with the organization of gamelan music. As we hear in example 6.11, the overall effect is repetitious but luminous, as the chiming sound of the instruments is attractive and resonant.

Braid rewards attentive listening: as we get used to the repetition of pitches, the introduction of each unfamiliar note offers a small but refreshing change. Like Riley’s, this music is based on incremental, gradual changes, which are intended to draw the listener into a state of contemplative attention—a strategy sometimes called minimalism.

This appropriation of gamelan music conveys a different sentiment than Page 170 →did Riley’s or Harrison’s adoptions of Asian music. Riley and Harrison wanted their listeners to recognize the source of their borrowings: in order for the political meanings they associated with their music to be effective, the listener had to at least get as far as the generalization “that sounds Asian.” In contrast, unless the listener happens to be familiar with the Indonesian tuning of the scale or the chiming sound of the gamelan, Benary’s music makes no reference to any specific place or people.

Rather, Braid more closely resembles other minimalist pieces that were based on “found sounds,” snippets of spoken-word audio that would be looped into repetitive blurs.41 The composer Steve Reich’s 1966 tape piece Come Out exemplifies this technique. In it the voice of Daniel Hamm, a black man arrested for a murder he did not commit, describes the bruises he sustained when he was beaten during his arrest. His words are grim: he says he had to “open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them” that he was really injured. Yet Reich (1936–) treats the words as musical sound rather than as a meaningful statement. The words “come out to show them” repeat until they lose their verbal sense; then the tape loop is played against itself but offset in time (example 6.12). Later, Reich manipulates the loop further, creating peculiar blurring effects.

In these pieces both Benary and Reich acted as mediated selves: what they took as “found sound” was someone else’s art or someone else’s voice. Indeed, the voice (or in Benary’s case the instrumental sound quality) retains some of its recognizable qualities even as it has been metamorphosed. As the music theorist Sumanth Gopinath has pointed out, Reich’s use of Hamm’s recognizably black voice points to many possible meanings: the struggle for civil rights, the violence done to persons (as violence is done to the voice on the tape), and the imprisonment of African Americans.42 Although the vestiges of Indonesian music that remain in Benary’s Braid—the sound quality of the gamelan and the tuning—point to a vague “elsewhere,” the piece itself seems quite abstract.

Like Riley’s, Benary’s demand that the listener pay close attention to small changes points to a way of life that contrasted with US life in the 1960s (or today). Most of the composers who made minimalist music had some attachment to music from other parts of the world. At the same time, Benary’s use of gamelan seems to bear much less predetermined meaning than do Harrison’s, Riley’s, or Reich’s borrowings: there are fewer cues that point the listener to interpret the music in a particular way. Although the listener who has prior knowledge of gamelan may associate Benary’s Braid with Indonesian music, those without such knowledge seem more likely to accept the piece as “found sounds.”

The composer Asha Srinivasan (1980–) also works with blended traditions in a New Music context. Srinivasan comes from a family of musicians and immigrated to the United States from India as a child. In her childhood Srinivasan learned about Carnatic (South Indian) musical traditions, but her interests drew her to the Western music available through US public schools. Through undergraduate and graduate study in the United States, she has acquired expertise in a variety of Western musics, including composition for electronic instruments. As an adult she has chosen to explore Indian music again by studying it on her own. In a video posted online, she refers to herself and her music as “hybrid”: she freely blends elements of various traditions together.43

Srinivasan’s Janani exemplifies that mixture. The 2009 version of Janani, which means life-giver or mother, is composed for a piano and four saxophones.Page 172 → In Carnatic music a raga (or mode) consists of a particular collection of musical notes, associated with certain characteristic ornaments and bent notes, that provides a basis for improvisation. Srinivasan explains that the piece makes use of two ragas: one that shares her mother’s name, Lalitha (example 6.13), and another that is her mother’s favorite, Ahiri (example 6.14).

Link: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9853855.cmp.99

Example 6.14. Raga Ahiri, audio examples at the website Raga Surabhi.

When Janani begins, we hear a drone played on the piano, but the sound is not made by pressing the keys: the player reaches inside the piano to pluck the strings repeatedly, occasionally sweeping a fingernail across them to create a dense resonance (example 6.15). The sound quality of the plucked piano strings resembles that of a tambura, an instrument that exists in Carnatic and Hindustani traditions, whose strings sound a drone (example 6.16).

The saxophones enter with a narrow range of notes near the drone note, then gradually expand, presenting more and more of the raga at a flexible, unhurried pace. This strategy is very like the introduction to a performance of Carnatic music. Beginning at timepoint 2:35 in Janani (example 6.15), the pace becomes steady: the introduction of a regular pulse corresponds to the next phase one would expect if this were an Indian piece. The music builds to a point of maximum intensity, only to pause suddenly at 4:30. The rest of the piece moves at a brisk pace while exploring the Ahiri raga. From 4:52 most of the ensemble keeps the rhythm while the soprano sax wails above them: a similar texture is heard in both North and South Indian music, usually as a reed instrument accompanied by drumming.44 Although the overall progressionPage 173 → of a slow and free section, followed by the introduction of a steady pulse and the gradual intensification of energy, resembles Carnatic music, the time-scale of the piece does not: at about seven minutes, Janani proceeds much more concisely through the sequence.

Even as it relies on Indian models for its form and choice of notes, this music also resonates with both jazz and New Music. The choice of instrumental sounds plays a key role here. The technique of plucking and sweeping the piano’s strings, which in Janani sounds like a tambura, originated with Henry Cowell, who composed experimental piano pieces in the 1920s (example 6.17).

The choice of saxophones for this piece is compelling, too. Depending on what previous experience the listener brings, this sound can mean different things. For a listener familiar with South Indian music, the sound of the saxophone resembles that of the nagaswaram—a larger version of the shahnai we heard earlier in this chapter. Music for this instrument is often lively and loud, and two or more can be played together, as in example 6.18.

For listeners who are unfamiliar with the Indian referent, the high wailing of the saxophone and the many expressively bent notes in Janani may recall how saxophones have been used in jazz. For example, Johnny Hodges’s solo “I Got It Bad,” recorded with Duke Ellington and his orchestra in 1958 (example 6.19), makes full use of the instrument’s expressive qualities, with a great deal of glissando (sliding between notes).

Page 174 →

Srinivasan has notated the glissando effect in the performers’ instructions for Janani, and she instructs the player to emphasize them, making them “long and deliberate.”

Another characteristic effect is the way the saxophone section of a big band often plays together with precision. We hear such an effect in example 6.20, “Three and One” performed by the Thad Jones and Mel Lewis Orchestra. The players play as one, in close harmony: even the fast notes and bent notes stay in sync with each other.

This “tight” style of playing remained an important element in virtuosic jazz as well as in New Music. In the late 1960s and 1970s the saxophonist Anthony Braxton began performing what he called “creative music,” which appealed to people from concert music and jazz circles who were looking for edgy modern music. That sense of being up-to-date and novel was a key element of New Music just as it was for avant-garde jazz musicians: Braxton worked between these musical communities, connecting them. Braxton’s style featured a great deal of fast unison playing—for instance, in his Composition 40M (example 6.21).45

The tight precision we hear among the lower saxophone parts in Janani at timepoint 6:07 resembles this virtuosic manner of performance and connects Janani to the traditions of New Music as well as jazz.

A fan of Euro-American concert music might bring still other reference points to their hearing of Janani. At timepoint 2:35, the moment at which the pace becomes quicker and the beat more regular, the lowest-pitched saxophone sets up a busy pattern. Starting at timepoint 2:51, the higher-pitched saxophones play a new melody high above. This moment feels like a new beginning—it might remind a concert music fan of Darius Milhaud’s Creation of the World, a European ballet from the 1920s that begins with a prominent saxophone solo over repetitive patterns (example 6.22).

Srinivasan may not have intended all these resonances between Janani and other musics: different listeners will bring different kinds of knowledge to the piece and make different associations. One of the things that makes Srinivasan’s music remarkable is its place at the nexus of many kinds of music. Listeners may enjoy the music whether they hear any, all, or none of these resonances, for Janani is exciting to listen to, with pacing that draws the listener in and an energetic conclusion. In a note accompanying the piece on her website, Srinivasan identifies the ragas and their connection with her mother but does not emphasize all the ways in which Janani draws on Indian music.46 Unlike Riley or Harrison, Srinivasan does not require her listener to consider the particular sources or referents of her music, nor does she rely on a particular interpretation of what “India” might mean. Rather, her music stands open for listeners to make meaning of it themselves.

Courtney Bryan is a composer and pianist whose expertise includes concert music and jazz. Bryan composed Yet Unheard, with words by Sharan Strange, for a memorial concert. Its first performance took place in 2016, on the first anniversary of the black activist Sandra Bland’s death in police custody in July of 2015. Unlike Olly Wilson’s Sometimes, in which New Music and African American traditions contrast with each other, Bryan’s piece absorbs a variety of elements into a more seamless personal style.

Yet Unheard (example 6.23) begins with tones that are dissonant (sounding harsh together) and slide downward (timepoint 0:27).

This kind of sound has traditionally been used by concert music composers to signal lament. As more instruments enter, they play in imitation: groups play similar parts but begin at different times so that they overlap (from timepoint 0:52). When the harp and flute come in (timepoint 1:19), they play melodies that wind around on an upward path. Bryan’s overlapping patterns of sliding string sounds recall a piece of European New Music from the 1960s, Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima—another work laden with grief and horror (example 6.24, especially the passage after timepoint 2:27).

Link: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9853855.cmp.110 (listen at timepoint 1:47 to 3:32)

At the same time, Bryan’s use of imitation and dissonance brings to mind the very beginning of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, an oratorio that dramatizes the story of the death of Jesus as told in the Gospel of Matthew. Bach’s melodies, too, share the winding quality of Bryan’s harp and flute lines: they turn back on themselves, as if they are knotted up (the Bach is example 6.25). In both cases the introduction acts as a framing device, setting the stage for the particulars of the drama.

The words of Yet Unheard also allude to Bach’s Passion. Bryan’s chorus begins with “Mother, call out to your daughter” (example 6.23, timepoint 1:40) much as Bach’s chorus starts with “Come, daughters, help me lament” (example 6.25, timepoint 2:02). In both pieces the chorus acts as narrator and commentator, and solo voices act as particular characters (fig. 6.3). The stories of Bach’s and Bryan’s oratorios resonate but differ in important ways. Bryan’s music, like Bach’s, portrays the death of an innocent. Bach’s oratorio ends with a choral lament after the crucifixion of Jesus: the Christian Passion story ends in darkness, before the Easter resurrection. But in the introduction to Yet Unheard the chorus urges us to “push back hatred’s stone” and hear Bland’s voice—a reference to the Easter narrative, when Jesus’s friends push back the stone and find he is no longer in the tomb. Like Jesus, Bland spent “three days in a cell”: this comparison offers a possibility of resurrection through memory that is not possible in actuality. Through this mixture of imagery Bland seems to be at once dead and resurrected—simultaneously mourned and present in spirit.

Indeed, we hear her presence. At timepoint 2:53 of Yet Unheard (example 6.23) a solo singer enters, singing words written from the perspective of Bland herself, recalling the day she died. In Bach’s oratorio Jesus, the central character, hardly speaks at all, but the words presented from Bland’s perspective take a central place in Bryan’s narrative. The soloist’s voice edges painfully upward, Page 177 →accompanied by mysterious flute trills that yield to a military-sounding trumpet when she asks: “And my power, robust, unbidden, was it too much on display? Did that drive his anger to kill me that day?” The frequent presence of the jangling, metallic triangle contributes to a sense of emergency in this music.

Immediately thereafter, on the words “Didn’t he kill me that day,” the singer adds one phrase that sounds like it is built on a blues scale; it descends into the lowest notes she can produce (timepoint 4:36). Hints of blues appear again at “Tried to kill my dignity too” (timepoint 5:52) and in the choir’s response on the words “black people” (timepoint 7:02). These references are fleeting, and they quickly surrender to the overall tense sound of the work. Perhaps the suppression of the blues references reflects the choir’s message at that point: “We’ve forgotten how to imagine black life. . . . Our imagination has only allowed for us to understand black people as a dying people.” Only at the end of the piece (after timepoint 14:06) do we hear a last bit of blues when the singer, as Bland, wails above the choir and orchestra, “Won’t you sing my name,” an outpouring that descends along a blues scale as it disappears again into the abyss of the singer’s lowest tones.

The music Bryan has created in Yet Unheard draws on multiple sources—oratorio, New Music, blues—to achieve its effects. Yet the experience of the Page 178 →music does not suggest quotation or mashup but an unrelenting outpouring of grief. That is not to say that there is no trace of Bryan’s African American heritage here; indeed, the work as a whole is framed as an outcry specifically from the African American community, echoing the hashtag #sayhername that Black Lives Matter activists used to protest police brutality. As a 21st-century composer, Bryan chooses various musical styles for her compositions; she is free to move among the traditions as she wishes and to integrate them as she pleases.

The “first-generation” mediated composers described in this chapter appropriated music for various reasons: one reason was to signal a political allegiance. In the music of the three “next-generation” composers discussed here—Benary, Srinivasan, and Bryan—the overt signaling of difference has become more subtle. These composers still choose musical styles based on what each style means to them and what it can convey to listeners. But they draw less attention to the markers that proclaim appropriation—allowing different musics to meld together into something new. The emphasis here seems to be on a smoother integration of different materials, creating something that may not immediately reveal itself as “mixed.” Bryan aptly characterizes herself as a “composer and pianist beyond category.”47 No preexisting genre label is sufficient to describe her creative contributions.

Globalized Generations

As we saw in the early chapters of this book, musical borrowing, assimilation, or appropriation across lines of power have had stakes both political and personal. In cases where the socially empowered borrow music from the less powerful, appropriation has often felt like disrespect or theft. Those effects persist in the mediated era, yet the wholesale appropriation of styles has also become commonplace and a matter of individual choice. As a large and growing archive of recorded music is available for reuse, and travel and circulation of media have made it possible to know more kinds of music, composers have begun to treat it all as available for their use. Sometimes an element of exoticism plays a role in the selection of music to borrow, but often, as we have seen, the purposeful choice of a style has also served as a form of personal expression, a means of representing oneself and one’s allegiances in a particular way.

In chapter 8 we will return to the idea of appropriation for the purpose of making blended music. The Argentinian anthropologist Néstor García CancliniPage 179 → describes appropriation of this kind as a creative act of the individual, and he asks us to examine closely the strategic nature of appropriation. What is the borrower trying to accomplish through musical appropriation? Is the composer gaining entry to places or ideas that would otherwise be forbidden? Is the composer developing a personal identity that is meaningful and distinct from peers’ identities? Does the appropriation make this composer seem more modern or more traditional?

We know that musicians habitually pick up new and fascinating sounds, possess them, and sometimes weave them into their own music-making. For the first mediated generation described in this chapter, borrowing was often a refashioning of identity: rejecting some part of their prior education, composers appropriated music to flag their opinions and affiliations clearly. The next-generation composers discussed above proceeded in various ways. In the tradition of New Music, Benary’s appropriation was absorbed into an abstract musical process, losing its Indonesian associations. Srinivasan and Bryan, like Wilson before them, participate in more than one “home” tradition. Unlike Benary, Bryan and Srinivasan do not conceal their source music, but they do minimize the contrast between traditions, creating a thorough blend. As composers who move between New Music and other traditions, they might use this blending as a means for moving back and forth—or for resolutely standing in the doorway, giving up neither identity in favor of the other.