1.2: Colonialism in Indonesia

- Page ID

- 172094

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Music Moving with an Occupying Force

Music has often circulated along the routes established by trade, warfare, or political alliances, for these activities move individuals and peoples, bringing them into contact with each other. This chapter describes how these relationships have shaped music-making in the tropical Southeast Asian islands we now know as Indonesia. These islands have long been connected to faraway places. In the sixth and seventh centuries CE seafaring traders linked the islands to China, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa. When the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived in the region in 1498, he saw great opportunities for profit in these active commercial networks. The Portuguese inserted themselves into these networks using military force. They terrorized the population of coastal trading towns, built fortified enclaves, and began trading from within those enclaves, using their cannons to protect their transactions and trading partners.

To make this system profitable, King Manuel I stationed administrators, traders, and soldiers in these enclaves to keep them under control. The Portuguese established trading colonies for exchange of goods and reprovisioning ships; plantation colonies, in which they used local or imported labor to gather natural resources for export; and colonial settlements, in which they brought sizable groups of Portuguese people to take territory and forcibly control the population that was already there.1 As I noted in the introduction, this practice of institutional control by one people over another people, their territory, and their resources is known as colonialism.

Some colonies maintained a strict separation between colonizers and colonized, but many produced blended societies that maintained customs from both groups. Often the colonists were men who would marry local women or use them as concubines.2 Thus, colonialism is one way in which populations Page 20 →from one place end up taking root in another place. Over its long history colonialism has reconfigured the world’s peoples and brought musics from afar into contact with one another.

Colonialism is a broad concept about human relationships, encompassing both forcible domination over a group of people and all the social consequences of that domination. Colonial relationships have also determined how the world’s peoples have been governed and how they see themselves as part of larger political groupings. The hierarchical combination of a ruling state and its ruled provincial territories is called an empire. The hypothetical ideal of a nation-state presumes a homogeneous population who are governed by more or less the same rules (with the notable exceptions of differentiation by gender and social class). By contrast, an empire is a state in which different populations are granted different rights and are subject to different laws.3 When the Portuguese established colonies, the people they subjugated abroad were treated differently from the people in Portugal. The colonizing forces enslaved the people in the colonies or otherwise put them to use according to profitability and convenience, maintaining control over them through violence.

The Portuguese were not the only Europeans working to establish an empire. The Netherlands, already a banking powerhouse, also sought entry into global trade routes. In 1602 powerful Dutch families formed the private Dutch East India Company, representing stockholders from six cities. The Dutch were at war with Spain and Portugal; this war was fought not only in Europe but also overseas, with the heavily armed Dutch East India and West India Companies standing in for the Dutch Republic in Asia and the Caribbean. The Dutch gained wealth and power by pillaging Portuguese ships and enclaves throughout South and Southeast Asia, coastal Africa, and South America. The Dutch East India Company established profitable trading bases along the coastlines of India, Asia, and southern Africa (fig. 1.1). At the end of the 1600s this private company effectively ruled over 50,000 civilians and 10,000 soldiers.4

Conflicts with the British Empire and the difficulty of managing employees at great distances led to the bankruptcy of the Dutch East India Company in 1798. After that, Java, Sumatra, and other territories held by the company became colonies of the Dutch nation-state, the Netherlands. Most of these islands remained under Dutch control (except for brief takeovers by French and British colonial forces) until the Japanese conquered them during World War II. Dutch people lived among the rest of the people on the islands, but they instituted different classes of citizenship, with separate laws applying to Page 21 →groups labeled as European, Indigenous, and Foreign Easterners (covering the large Chinese minority and other non-Indonesian Asian people).5

Page 22 →

The long-standing European presence in the islands that would become the state of Indonesia has had a formative influence on musical practices both on the islands and in Europe. This chapter describes musical relationships created by colonial relationships, drawing its key musical examples from Indonesia. In these case studies we will see how colonialism made permanent additions to Indonesian musical traditions. Musically, the influence went both ways: colonialism changed European culture, too.

Entertaining the Dutch: Gamelan and Tanjidor

As colonists who could take what they wanted by force of arms, administrative officials of the Dutch East India Company settled into comfortable lives near their trading base on the island of Java. In the 1700s many moved to the outlying areas of Batavia (now Jakarta) and formed little kingdoms of their own, with “splendid houses and delightful pleasure gardens”—many of them maintained by enslaved people.6 The colonial officials blended European habits, such as wearing top hats and keeping racehorses, with Javanese habits, such as going barefoot and segregating men from women in public ceremonies. Because most of the administrators’ families were Eurasian owing to intermarriage, and their household servants came from the island, the furnishings, food, and music in their homes were often a mixture of traditions.7

One such member of this elite social class, Augustijn Michiels, exemplifies the musical mixture as it was practiced at the end of the 1700s. He owned a city estate in Batavia and two properties out in the country, and they were filled with music. According to the historian Jean Taylor:

Michiels’s arrival on one of his estates was like the triumphant progress of royalty, with inhabitants of his lands playing the gamelan (an ensemble of Javanese musical instruments) in welcome and all the hamlet heads in procession. Michiels dressed in Indonesian costume and preferred to sit on a mat rather than a chair. His food was Indonesian and his day punctuated with the afternoon siesta. Female slaves waited at table, and his guests were entertained with music from his slave orchestras and by troupes of ronggeng (women dancers). At Citrap he also kept topeng (masked) dancers in his employ, and his Page 23 →retainers there numbered 117 house slaves and 48 free servants, in addition to the stable hands and outdoors staff.8

This description offers us a glimpse of the hierarchy of power operating in a colonial house, as well as a sense of the intermingling of people and sounds.

One form of music on Michiels’s estate was the gamelan—a set of percussion instruments, struck with hammers or beaters. A gamelan includes large and small bronze gongs and instruments with metal keys (shaped like the keys of a xylophone) that are struck with a hammer. Depending on the regional tradition, the gamelan may also include singing as well as a variety of nonbronze instruments, including drums, a bowed fiddle, flutes, zithers, and (wooden) xylophones. Although gamelan from Java are the best known in the West, ensembles of gongs and chiming instruments also exist on many of the surrounding islands: only recently did they all come to be called “gamelan.” Java’s kings employed servants as musicians at their royal courts and kept gamelan in permanent outdoor pavilions. Gamelan music has also been used to accompany ceremonial events in villages, both in religious ceremonies and for festive processionals, such as that of wedding guests.9 The performance of a gamelan often includes dance or shadow puppetry. The video in example 1.1 gives a sense of what these instruments look and sound like.

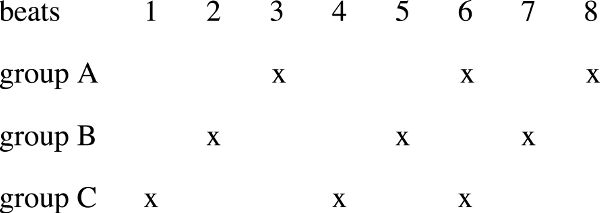

Gamelan music is organized in layers, which proceed with mathematical precision. The largest hanging gong plays the slowest part, entering to punctuate and define the progress of the music. Smaller gongs, set in cradles, play a melody in the low-pitch range, moving several times as fast as the largest gong. The xylophone-like instruments, which play higher pitches, sound embellishments twice or four times as fast as the middle-register gongs. A piece of gamelan music is organized in repeating cycles: the sounding of the largest gong announces the imminent arrival of the next cycle. The overall effect is one of interlocking strata that create a larger whole, as depicted in figure 1.2.

In example 1.2 you will hear the ensemble playing in unison (all together) with an emphatic flourish that gets the piece started. In example 1.3 we hear Page 24 →the layering effect. The music is punctuated at regular intervals by strikes on a large gong, which sounds a little “out of time” (audible in example 1.3 at timepoints 0:03 and 1:01).

The gong marks the last beat of a cycle and announces that a new cycle of music is about to begin. Throughout most of this piece of music, you hear a loud melody that moves very deliberately, at roughly one note every two seconds. You also hear softer notes moving four times as fast as that melody, and some higher, gentle notes move twice again as fast. Your attention probably drifts among these different levels. Javanese musicians would probably say that the real melody emerges from the whole effect, not from any one part.

In contrast, the slave orchestra that played European music on Michiels’s estate was a newly created colonial enterprise. Enslaved people in the Dutch colonies were entirely at the mercy of their masters. Most were enslaved for a lifetime, though some female slaves were able to access a measure of freedom by entering Christian marriages with colonists. High-status Europeans required enslaved musicians to play European music on European musical Page 25 →instruments as entertainment during dinners and leisure hours. They also played military music in public parades celebrating the colonial rulers. These small orchestras were highly valued, and slaves who could make music fetched a higher price than those who could not.10

The role of these orchestras changed over time. As the power of the Dutch East India Company waned near the end of the 1700s, some Dutch people wanted their blended Eurasian culture to look more like Europe’s, so they cultivated European music with renewed intensity.11 In the 1800s some Javanese held public concert series that included European folk, dance, and military music, as well as symphonies and other works from the European classical tradition. Franki S. Notosudirdjo is an ethnomusicologist who reports that “music was a profession in the colony.”12 A steady stream of imported music arrived from Europe, as well, including music teachers and visiting opera companies.13

The enslaved musicians probably participated in both the gamelan and the orchestra. (In 1833, when Michiels died, his family auctioned off 30 enslaved musicians and their instruments.) Notosudirdjo writes that the music the slave orchestras played was European dance music: “the pavane, quadrille, and later on in the 19th century, the waltz, mazurka, polonaise, and pas-de-quatre.”14 Some also played in the style of a military band for parades. These Western musical instruments and styles were part of regular life for European and Eurasian colonists and for Javanese slaves for a few hundred years. They became part of the social norms on the island. The experience of the slave orchestras is believed to be the origin of tanjidor, a kind of music that is traditionally made by Javanese people using Western instruments and Western musical forms.15

The basis for tanjidor is the European brass band, to which other instruments may be added. The slave orchestras were asked to play European music so that the Dutch colonists could dance. Compare examples 1.4 and 1.5. Example 1.4 is a waltz: a European dance popular in the 1800s, famous for its “oom-pah-pah,” 1-2-3 rhythm.

Example 1.5 is a sample of tanjidor, entitled “Was Pepeko”—the word Was means waltz, and this music retains the “oom-pah-pah” rhythm of its European model.

In this example you hear a clarinet, trombone, tenor or alto horn, helicon (a type of horn produced in 1800s Europe), snare drum without snares, and bass drum. The ensemble also includes Javanese percussion instruments: you hear gongs and kecrek (clashing metal strips mounted on a block and struck with beaters). This kind of music would have played a role as entertainment in a rich colonial house. It is suitable for dancing or just listening.

Although tanjidor originated with slave orchestras, it became a musical tradition in Indonesia, extending after slavery ended in the 1800s. In the early 1900s bands of tanjidor musicians would play for tips at weddings and celebrations of the Chinese and European new years.16 The tradition was interrupted by both World War II and government policy, but it is still played by Indonesian people in rural areas. Tanjidor ensembles do not play only European music; they also borrow music from the gamelan repertoire, from Chinese music, and from Indonesian popular songs.17

Example 1.6 is an example of tanjidor from the north coast of Java. This audio example has some gamelan-like qualities: once it gets going, it includes layered levels of rhythmic patterns that interlock in systematic, hierarchical ways. Typical of tanjidor, it is played on a mix of Western instruments with some Javanese instruments. You hear an oboe-like instrument, a bass drum and snare drum (played without snares, and with hands instead of sticks), a trombone, and some percussion instruments from the gamelan.

But apart from the instruments on which this music is played, the music itself sounds nothing like any European model. This is an example of localization; that is, a musical practice from elsewhere has been altered to fit local conditions and become part of local traditions.

In the case of tanjidor we see that colonialism had a marked effect on how and for whom music was made. The Dutch used ruthless military force to rule over people on the island of Java. But they also used the force of custom to Page 27 →create and maintain social divisions between ruler and ruled, between Dutch and Javanese.18 Music played for the rulers’ pleasure was one such custom. First under the Javanese kings and then under the Dutch colonial administrators, music was used to delineate a separation between master (who could demand music) and servant (who must play the music the master chooses). Creating and enforcing that separation transformed existing musical practices and introduced new ones. One cannot really say that tanjidor is European music, for it was first made in Indonesia. This musical style has existed there for a long time, but it is not indigenous music. Yet tanjidor is a traditional music: Indonesian people hand it down because they value it. This music emerged from contact between peoples and their traditions and from the unequal power relationship built by colonialism.

Java on Display: The Universal Exposition in Paris

The establishment of long-distance connections through colonialism also moved music out of its places of origin. As a result of the colonial relationship between the Dutch and the Javanese, gamelan music from the Indonesian islands became known in Europe. In 1889 the city of Paris hosted a six-month extravaganza called the Universal Exposition. Nation-states and private enterprises sent exhibits of their achievements in arts and letters, as well as examples of their latest technical innovations, which were displayed in a vast Gallery of Machines. The United States was represented by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, featuring the sharpshooter Annie Oakley; the show dramatized the conflict between white colonists and Native Americans.19 The Eiffel Tower provided an impressive front door for the Exposition, and live demonstrations of the telephone and the Edison gramophone drew crowds.20 New train lines were built to carry people swiftly into the city.21 The Exposition attracted about 30 million visitors over its six-month run.

The Exposition included a large section called the “Colonial Exposition,” which included displays of homes from different parts of the world, constructed as living museum dioramas. Within these displays visitors could see hundreds of imported indigenous people who were supposed to represent the daily activities of colonized peoples, including handicrafts and music-making. The organizers of the Exposition treated the people who were on display as specimens, exemplars of their kind, rather than as individual people. A visitor exclaimed, “It was possible to see there twelve types of Africans, besides Javanese,Page 28 → Tonkinese, Chinese, Japanese, and other oriental peoples, living in native houses, wearing native costumes, eating native food, practicing native arts and rites on the Esplanade des Invalides side by side with the latest inventions and with the whole civilized world as spectators.”22 The Javanese village display attracted four to five thousand visitors a day on weekdays and nearly 10,000 on Sundays.23 Like animals in a zoo, the people on display were given a predetermined diet and were observed closely by anthropologists.

Indeed, the idea of anthropology—studying the customs of a group of people—stemmed from the need to regulate and control colonial populations.24 Just as the exhibits of modern technology allowed visitors to think of themselves as modern citizens, the exhibits at the Exposition allowed visitors to imagine a whole world, divided into civilized and primitive peoples, with the visitors on the civilized side and the colonized peoples on the primitive side.25 The souvenir plate in figure 1.3 reveals this division: it depicts the Javanese dancers but also calls their hairstyle “bizarre” and mocks them by comparing them to “primitive firefighters.” Visitors to the exhibition did not define “modern” as an absolute quality; rather, they based their judgment of who was modern on comparisons with other peoples, who might be characterized as primitive, indigenous, or folk. Europeans could call themselves modern to draw attention to the difference between themselves and others. At the same time, they did not think of the “modern” as specific to their value system; they believed that it was a universal quality, a norm that everyone around the world should aspire to.26

Whereas European music was presented in scheduled concerts in concert halls during the Exposition, music from Europe’s colonies was offered within the diorama displays at the Colonial Exposition. These performances were framed as a way of bringing the experience of the world directly to Paris: if Europeans did not want the inconvenience of traveling, they could see the genuine inhabitants and customs of other lands at the Exposition. The press framed these exhibit-performances as an educational event, but their primary attraction lay in the vivid experience that stimulated Europeans’ imaginations with thoughts about faraway places.27

It appears that viewers and listeners at the Javanese pavilion heard some Sundanese (from west Java) and some Javanese music. But they did not receive explanations about what they were seeing and hearing in these performances. Indeed, it is likely that they could not hear everything: the exhibits were not fully separate, so the sounds from different exhibits and the crowds blended together. It may have been hard for witnesses to even identify what they heard Page 29 →as music, let alone listen to it with full attention. Nonetheless, many visitors were captivated by the musical performances: by hearing what they perceived to be primitive music, they could better understand themselves as “modern” people.

French people had already been exposed to ideas about Asian music, but those ideas had been presented to them through their own music. In the late 19th century French composers of concert (or “classical”) music were interested in faraway places; they wrote operas and songs about those places. But most French citizens would not have had the chance to travel abroad, nor would they have heard Asian music as it was performed by Asian people. The Dutch had sent a gamelan to Paris as a present several years before, but no one knew how to play it, so it remained a museum piece. The Exposition was thus a rare opportunity to witness this music in person.28

The musicologist Sindhumathi Revuluri has described how some French listeners tried to write down the sounds of the gamelan for later study or performance. They found the rhythms difficult to capture, both because they were novel and because they fit so poorly into European understandings of Page 30 →music.29 One scholar, Julien Tiersot, met privately with the Javanese musicians to have them play the music again more slowly, so he could hear it better. He wrote down excerpts in the European system of symbols used for classical music (music notation), along with a great deal of verbal description of the performances. Of course, the European system for capturing music on paper could not capture many elements of the gamelan performance. These instruments were not tuned to the notes of a Western musical scale, so presenting them in Western notation was inaccurate. Louis Bénédictus went still further, altering the Javanese music to fit French concepts. In a publication entitled “Bizarre Musics at the Exposition” he remade the gamelan music into pieces that could be played on the piano.30 These pieces reduced the complexity of the gamelan to what could be played by one person and eliminated the special resonant sound of the metallic gamelan instruments. Bénédictus also changed the melodies so that they would reflect a French idea of tunefulness. Yet, as Revuluri has pointed out, they are not typical French piano pieces of their time. Bénédictus’s versions did capture some of the rhythmic density, percussive textures, and sudden shifts in timing that seemed special about the gamelan.31

The Exposition reflected an attitude typical of its time: a fascination with the “other” people of the East. Fascination with the unfamiliar is known as exoticism: this fascination is fueled by the knowledge that the observer has more power than the observed “other.” The particular kind of exoticism that focuses on an imaginary East is called orientalism.32 Some French listeners were charmed and enraptured by the gamelan music in this way. One eyewitness, Émile Monod, wrote that “like the crystalline sounds of faraway bells, the plaintive peace of this languid tonality seems to express vague pains and cradles us deliciously.”33 He found the gamelan charming precisely because it was different, and he used orientalist stereotypes of the unknown East (“languid,” “vague”) as well as sensuous language (“pains,” “cradles us”) to express that attraction.

Some people heard the gamelan as evidence that people in the colonies were indeed primitive, as compared to the modern people of Europe. Monod reported: “The Javanese gamelan, the Arabian oboes, the Annamite [Vietnamese] violins, etc. are of great interest from the point of view of the history of music; the interest is less from the point of view of production for these instruments have not changed for centuries. Conversely, European music has progressed constantly.”34 The French musician Claude Debussy (1862–1918) admired the gamelan for the new and complex sounds it offered. Reversing Page 31 →Monod’s claim, Debussy wrote that “if we listen without European prejudice to the charm of their percussion we must confess that our percussion is like primitive noises at a country fair.”35 Where the critic was eager to use the music as an occasion to point out the superiority of the French, Debussy rejoiced in new sounds from afar. Both the disdain and the fascination are elements of orientalism.

What Debussy loved about this music was not necessarily the same thing individual Javanese might have loved about it; he was interested in new musical ideas from the Western perspective, and the Javanese system offered a way of making music outside of the Western tradition of harmony. Oddly, gamelan music also appealed to Debussy’s French national pride. This was not because the Javanese had anything to do with the French. Rather, because so much of traditional classical music was German in origin and was dominated by German composers and techniques, some French musicians of Debussy’s generation were looking for nontraditional, non-Germanic ways of organizing their music. As far as Debussy was concerned, music that presented a new alternative was welcome.

During and after the Universal Exposition, the arts became a means to express an awareness of colonized peoples and the social inequality of colonial relationships.36 Debussy experimented with using the sounds of Javanese gamelan in his own compositions. Listen again to some of example 1.3, recalling its different layers of rhythmic activity, some moving slowly, some moving twice or four times as fast. Then compare example 1.3 to example 1.7. Example 1.7 is a piano piece called “Pagodas,” completed in 1903. The texture of this piano music at timepoint 0:52 closely imitates that of Javanese gamelan music, with different, pulsating layers of activity.37 By the end of the piece (timepoint 4:34) Debussy has introduced a very fast layer of ornaments above the slower activity.

Debussy imitated the gamelan in other ways, too. Sometimes the performers of a gamelan play in unison to create a dramatic effect. You can hear an example of this effect in example 1.2 at timepoint 0:13. Debussy used this effect in “Pagodas” (example 1.7) at timepoint 2:23, among other places. Especially at the climax of Debussy’s piece (starting timepoint 4:02), low notes on the piano imitate the strokes of the largest gong.

Page 32 →As Revuluri explained, Debussy’s imitation was far from exact: it is like a reminiscence of what he heard at the Exposition, translated into a French musical style and transposed to a Western musical instrument. A gamelan and a piano are tuned differently. Debussy often uses groups of six rather than four fast notes, creating an imprecise wash of sound. Most important, his piece is not organized in cycles. Instead, it follows a classic European form: it begins by introducing musical ideas, moves away from them in the middle, then returns to those ideas at the end. Nevertheless, the overall effect is an unmistakable imitation of the gamelan sound.

Ultimately, Debussy became dissatisfied with the fashion of borrowing ideas from afar. He wrote that Western versions of folk music “seemed sadly constricted: the additions of all those weighty counterpoints had divorced the folk tunes from their rural origins.”38 Here Debussy fell back on a particular idea of indigenous authenticity—the belief that the music had been played in a certain way since the dawn of time and should not be altered.39 Of course, no music is eternally the same. In this particular case individual Javanese composers had been adding to the gamelan tradition, creating individualized and identifiable works with titles, for at least a hundred years. The music scholar Richard Mueller has connected Debussy’s statement to the composer’s frustration in revising his Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra. Debussy found that despite his efforts, he could not reconcile the subtly changing texture of gamelan music with European music in a way that satisfied him.40

Debussy’s desire to leave the Javanese music untouched, in its supposedly natural state, was a romantic idea. This kind of thinking is like that of the anthropologists who treated the Javanese on exhibit as if they were specimens from another time, not another place. Thinking about groups of people as distinct unto themselves and totally separate in a way that nothing can overcome is characteristic of colonialism, which maintains rigid social divisions between groups to preserve a power structure. At the same time, though, Debussy felt an urge to experiment with these sounds himself, to make something new out of them, in part precisely because of the feeling of utter difference, utter novelty. Debussy was motivated by attraction to the music but also by the exoticism (and the racism that often comes with the exoticism) that was characteristic of his time. Debussy was not the only one who felt this fascination. Some European musicians even traveled to Java to hear gamelan music.41

What are we to make of Debussy’s appropriation of the sound of gamelan music? It is not exactly theft, for the gamelan musicians lost neither the ability to play their music nor income as a result of Debussy’s composing “Pagodas.” Page 33 →From a musician’s perspective, the reuse is also not that unusual: musicians have a tendency to remember and imitate sounds they like, playing with them and incorporating them into their own music. Still, borrowing across colonial lines with an attitude of exoticism seems troubling, as it delineates a difference of power, with a wealthier and more powerful European person drawing on music made by less powerful people of color.

The literary scholar Homi Bhabha, who has spent his career studying the phenomenon of colonialism, calls situations like this colonial mimicry. According to Bhabha the colonizer makes an imitation of the Other that reforms it but keeps it recognizable, creating “a difference that is almost the same, but not quite.”42 In this context appropriating the music of a people can be a way to show power over them. But to create an imitation, the colonizer must engage with the colonized people, studying their ways, and this engagement threatens the wholeness of the colonizer’s culture by introducing foreign elements into it.43 Colonial mimicry creates new, blended artifacts and practices and shows how, once an empire is established, colonizers and colonized peoples are locked together in an uncomfortable but unavoidable relationship.

Indeed, even after Debussy stopped imitating gamelan music, some of its effects lingered in his music. Debussy had used six notes in the place of four to represent the quickest rhythmic level of the gamelan sound. He found that he liked that effect. He used it again in other pieces of music, and it was eventually absorbed into the French style of Debussy’s time. As Revuluri has explained, this effect, which began as an imitation of a French idea of Asian music, was no longer audibly Asian.44 Yet there it remained, a trace of the colonial relationship that was dramatized for Europeans at the Exposition.

Music and the Tourist Trade: Balinese Kecak

Another effect of colonialism is that it changes the marketplace for music in the colonized location, bringing in audiences from afar who make demands on performers. Even after colonies become independent (decolonization), tourism along trade routes established by colonists has delivered visitors; as audiences they, too, affect the musical scene. An excellent example of these effects is a practice called kecak (ke-chock), cultivated by amateur and professional musicians in Bali, a small Indonesian island east of Java. Kecak is a form of dance and drama accompanied by a special kind of vocal chanting on the syllable -cak (chock), performed by a male chorus.

Page 34 →At the time when kecak originated, this kind of chanting was performed in two different situations: a traditional sacred trance chant called sanghyang dedari, which was not performed as a drama, and a secular (nonreligious) form that is highly theatrical. In the sanghyang dedari ritual the “cak” chanting is used to accompany the dancers who enter an altered mental state; there is also a female chorus. In secular kecak the chanting of the male chorus is a form of entertainment that adds excitement to a drama (the female chorus is omitted). Balinese performers view these as separate kinds of performance: one is a religious rite, whereas the other is an artistic spectacle performed for tourists. According to I Wayan Dibia, a practitioner of kecak, both the sacred and secular versions are still performed, though the secular one is now much better known.45

In the secular form of kecak, heard in example 1.8, the male chorus, dressed in checkered sarongs over short trousers, sits on the ground in concentric circles. The chorus, which is responsible for the “cak” chant, takes on various roles to support the drama: sometimes they portray a monkey army or an ogre, at other times the wind or a garden. Sometimes the chorus sings in unison; at other times the chorus uses short syllables in interlocking rhythms that create a sound of busy complexity.

I Wayan Dibia has described the chant as a “voice orchestra,” presenting through vocal means the melodic phrases and rhythmic patterns that reflect those of the traditional Balinese orchestra (gamelan). Figure 1.4 shows one possible rhythmic pattern for the chanting. Performing ensembles can choose from among several different rhythmic patterns of this interlocking kind.46

A chorus leader chooses the tempo for the performance and cues the chanters to perform loudly or softly. A beat keeper imitates gong sounds with his voice, sometimes joined by members of the chorus. A narrator tells the story. Occasionally, we also hear solo singers, and sometimes the whole chorus sings a melody together. In kecak solo dancers perform intricate gestures that distantly recall the formal dance traditions of Balinese royal courts. Meanwhile, the gestures of the chanting chorus are informal: they sit cross-legged, stand, wave their arms, or bow in a praying gesture as the story requires.47

In a later excerpt from the same kecak performance (example 1.9) we meet Page 35 →Sita, the wife of Rama, who is the noble incarnation of the god Vishnu. Sita has been abducted. Near the start of the excerpt Trijata enters: she is the niece of the evil demon king Rahwana, but she has become Sita’s friend during her captivity. Sita and Trijata dance in an elegant and courtly manner, which befits their elevated social status. This scene includes a mournful song about Sita’s fate as a prisoner; sometimes we also hear narration through the spoken word. You can see the solo singer sitting among the chorus members, facing the camera. The chant is a nearly constant presence, sometimes loud and sometimes soft.

Partway through the performance, the warrior monkey Hanuman enters: he has been sent by Rama to contact Sita. At first she rejects him, but when he shows her Rama’s ring, she knows why he has been sent. In return she gives him a flower to take back to Rama.48 Especially noticeable in example 1.10 is the interaction between the performers and the tourists who have come to view the kecak performance. Although Sita and Trijata do not acknowledge the tourists, Hanuman makes a great stir by engaging the tourists, sitting with them, posing for pictures, and even checking tourists’ hair for bugs, as a monkey might. The tourists respond with typical tourist behavior, laughing and chatting. One even steps out into the performance space to take a photo of Hanuman with evident delight.

Page 36 →

The secular form of kecak has its origin in the 1930s. The German musician and artist Walter Spies, who had lived in Bali since 1927, was visiting a Balinese historic site. Spies was serving as the choreographer for a film entitled The Island of Demons, and he wanted a dramatic musical performance that would be exciting for the film. Spies suggested that the kecak sacred chant be combined with a dramatic performance of scenes from the Ramayana epic, an ancient Hindu poem, and he worked with the Balinese dancer I Wayan Limbak to realize his vision.49 According to Limbak, who played a role in Spies’s film, “The final form of the kecak was the result of a collaboration between Spies and village elders, with Spies determining the theme of the dance and its timing.”50 The film contained an exorcism scene, which represented the sacred sanghyang dedari ritual in abbreviated form, without the trance element. This was the first time the ritual was presented in a nonreligious context, though in recent years musicians have permitted tourist access to the sacred form.51 Although Spies seems to have played a significant role in the founding of this performing tradition, he insisted that the secular kecak was a Balinese creation.52

Indeed, Balinese people made this kind of performance into a tradition of their own. The Ramayana epic was already a thousand-year tradition in Bali, familiar to performers and audiences on an island where Hindus form the majority of the population.53 The importance of this Hindu drama had been reinforced by the Dutch administration, which promoted Hinduism in the 1920s as a way to contain Islam in the Indonesian islands.54 The musician I Gusti Lanang Oka and the businessman I Nengah Mudarya brought Spies and Limbak’s version of kecak to the village of Bona, refined its formal structure, and established “The Abduction of Sita” as a favorite scene.

Kecak also benefited from the Dutch policy of “Balinization”—that is, preservation of Bali in what the Dutch thought of as a pristine state. The Dutch colonized Bali much later than Java; beginning in the 1840s and continuing until 1908, they conducted military campaigns against the Balinese kingdoms that resulted in the violent deaths of many Balinese. That the European press covered this violence embarrassed the Dutch, who wanted to be regarded as benevolent colonizers. To repair their reputation, in the 1920s the Dutch forbade modernization in Bali and encouraged the restoration of the arts as they had been practiced in the destroyed kingdoms. This effort produced a self-consciousness among Balinese people about their own artistic life and how they wanted it to be understood by others. Outsiders typically viewed Bali’s arts and rituals as untouched by the West, but in fact these traditions had Page 37 →been revived and altered under Dutch influence.55 Spies’s activities were part of a growing tourist industry that supported and encouraged these revived rituals.

In the 1930s Bali was promoted to tourists as “the last paradise”: artists in the village of Bona continued performing kecak to entertain tourists arriving on Dutch steamships. Yet there is no record of Balinese people attending these performances, which appear to have been made exclusively for tourists. After the 1960s, kecak troupes were established all over Bali, especially in the south. The movement of large numbers of tourists supported the development of this long-standing institution of Balinese music. Today there are about 20 troupes that regularly perform kecak.56

Kecak is community-based music: people from a particular village work together to sustain a schedule of regular paid performances. Rather than using the income for personal needs, most of the money goes to community goals such as securing a water supply or restoring a temple. To fulfill this function, kecak is still performed for tourists. The people who organize kecak performances are in close contact with hotels, restaurants, and tourist agencies. Some troupes have permanent contracts with hotels.57

Over its 90-year history kecak has been subject to larger political and economic forces. During the Second World War Japan occupied most of the islands in the region, and many residents of the islands suffered war crimes. After declaring independence in 1945, Indonesians experienced years of violence and political instability as nationalists in favor of independence clashed with those who remained loyal to the Dutch. Under the “Old Order” Sukarno regime (1945–67) conflicts between Muslims and other religious groups overlapped with conflicts between communism and capitalism and between democracy and authoritarianism. From 1965 to 1967 the Indonesian Army and its vigilantes, supported by the US government, killed between a half million and one million people, many of them ethnic Chinese or actual and alleged members of the Communist Party. Under these conditions tourism declined sharply. Furthermore, Balinese nationalists hated the idea of foreign entities using their island as a museum, so they dismantled the Balinese tourism industry.58 Under the authoritarian but stable Suharto regime (the “New Order,” 1967–98), though, tourism was actively encouraged again, in part because Indonesia needed the income. In 1969 a new international airport opened at Denpasar, making Indonesia easier to reach.59

With this new wave of tourism came increased attention to the possibilities for revitalizing and promoting many kinds of Indonesian music, including Page 38 →kecak. Most notable is the effort to standardize kecak performance.60 In early kecak, performances presented fragments of the Ramayana epic; they did not attempt to tell the story in full, and even major characters could be omitted. They could also perform stories from other sources. Since the 1970s, though, kecak includes only certain standardized scenes from the Ramayana, and the selected story is presented in a more complete form. In kecak of the 1930s the chorus wore everyday clothes. Their costume has become more uniform over the years, with checkered sarong and red sash, as well as white dots on temples and forehead. Differences among kecak performances have become less a question of a director’s artistic vision and more a question of whether well-trained soloists are available for key roles.61

Today, that process of standardization persists. If one troupe makes an innovation, it spreads quickly and becomes standard. Indeed, this standardization is enforced by the marketplace. The ethnomusicologist Kendra Stepputat has pointed out that most tourists arrive at kecak performances on the recommendation of other travelers, guides, printed guidebooks, or hotel employees. Kecak troupes pay guides and tourist agencies to bring people to their performances, and they rely on these channels of communication. The tourism industry has real power over the content of kecak: tourist agencies or guides can and do refuse to send tourists to performances that do not adapt.

Of course, foreign tourists typically have no idea of these market pressures. They know that kecak is unique to Bali and that it is a “must-see” cultural attraction. Under the influence of their tour guides tourists overwhelmingly experience kecak as “authentic,” meaning that they perceive it as part of the long-standing heritage of people on the island, a tradition practiced by the entire population, handed down from generation to generation from time immemorial. There is no way for them to see that kecak is produced for their benefit and has always been made for tourists, not for Balinese people.62 In the case of kecak the invented tradition elicits from outsiders that feeling of experiencing authenticity.

This situation is not as unusual as it might seem. Eric Hobsbawm has pointed out that many traditions are “invented”: that is, they are constructed for the needs of the present, but they are made to seem valid by the use of symbols, rituals, and ideas from the past. The invented tradition is in large part a matter of representation. Appropriating older symbols helps to create the sense that the new practice is “authentic” or legitimate; it can help people feel part of a group; and it can help convince people of a new idea by couching it in familiar, traditional terms. According to Hobsbawm, traditions are Page 39 →invented more frequently in times of rapid change, and they frequently remind individuals of their citizenship, providing “flags, images, ceremonies, and music” that help them feel part of a nation.63

It is often not obvious that a tradition has been “invented.” In the case of kecak the invented tradition is designed to seem ancient. It tells a story known to be more than a thousand years old, and the style of presentation retains the resonance of ritual even though its religious elements have been removed. The solo dancers’ costumes look as though they belong to a courtly culture from another time. Even in the 1930s, the staging cultivated a sense of mystery. A visitor named Bruce Lockhart recorded in his diary that to enter the performance, one had to descend into a dark temple courtyard, lit only by torches. A Balinese performer gave Lockhart the impression that every male from the neighboring village was part of the presentation and that this performance was a regular social ritual in the villages.64 That the chorus wears relatively little clothing and chants rapidly on a single syllable conforms very well to visitors’ own stereotypes of indigenous peoples. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, an expert on the presentation and performance of heritage, proposes that this kind of performance is a form of virtual reality: it lets tourists see what they want to see by creating it for them.65

All of these strategies have worked for the marketing of kecak. According to Stepputat a narrator on the National Geographic Channel described kecak in these terms in 1996: “On the island of Bali, man becomes the animal of its origins—this is the famous monkey dance called the kecak. Over a hundred men portray an army of chattering apes from the Hindu epic poem Ramayana. There is no orchestra, only the primeval sounds of the chorus.”66 This perception of the kecak and the people who perform it as “primitive” forms a relationship between the tourist and the performer, between the Balinese and the visitor. Appealing as it is, kecak allows visitors to understand themselves as “modern” people in contrast to the presentation they see—even though the performers are their contemporaries. (This situation might remind us of the Universal Exposition of the 1880s.) Playing to other people’s insulting stereotypes is a tactic known as strategic essentialism: this tactic has allowed Balinese communities to access tourist dollars for their own purposes. As tourism constitutes some 30 percent of the Balinese economy, the cultivation of these stereotypes has proven to be a resource for postcolonial Indonesians.

Of course, kecak is a traditional music: it is taught by one performer to another, enabling group cohesion and earning money for community projects. Saying that kecak is an invented tradition does not make it less valid or Page 40 →meaningful than any other tradition. Rather, it is a way to point to the purposefulness by which kecak has been created and sustained. A tradition need not stretch back to the dawn of time to be real, and sometimes people craft their traditions to seem older than they are. Kecak would not fulfill its social purpose if tourists did not believe it was an old tradition. Giving that ancient impression is itself part of the tradition, as true of kecak in the 1930s as it is today.

Kecak serves as a reminder that what we can know from watching a performance is only part of what is really going on. Historians of the arts read many kinds of contextual clues: letters and photographs, interviews with musicians and bystanders, and observations about social relationships and the flow of money. No matter where a person stands in the scene—as a bystander, as a tourist, as someone who talks to the performers, as a viewer of YouTube—she or he will have access to only a partial perspective. What looks like an ancient practice to the outsider may merely be staged for the outsider’s benefit.

This question of perspective is especially important for understanding the legacy of colonialism. Early in the 20th century, more than 500 million people lived under colonial rule. Over the course of the 1900s, many of these colonies declared independence and became sovereign nations, a process known as decolonization. But long-established colonial relationships could not be erased overnight. Our present-day world bears the scars of these relationships.

Indonesian Music in the World

Given that the Indonesian islands have been so intimately connected with other places for so long, it is not surprising that some of their music has become important abroad. The ethnomusicologist Maria Mendonça has identified active gamelan groups in many places. We might expect to find these groups in the Netherlands, given the former colonial relationship, and in Singapore, Taiwan, and Japan, given trade routes. But gamelan ensembles also exist in the United States, Great Britain, the Czech Republic, Poland, Australia, and New Zealand. Mendonça explains that most of these groups have flourished not because of Indonesians migrating to these places but because people with no heritage ties to Indonesia experience an affinity for this music.67 Gamelan has been deterritorialized—unlinked from the place where it originated.

Since Debussy’s encounter with gamelan in Paris, gamelan has become not just a one-time encounter with an exotic curiosity but also a part of educationalPage 41 → and musical institutions. In England and Wales gamelan was included in the National School Curriculum for Music. Educators have been attracted to the sense of working together that is required to play interlocking parts. One teacher noted that gamelan is a lesson in civics: “you have to be responsible to everyone else in the group, no matter which part you play.”68 On the most practical level, a gamelan can be large enough to accommodate a whole class of schoolchildren, and the level of difficulty of different parts varies, so different musical abilities can be accommodated within the group. Because few Indonesian people live in Britain, gamelan seems egalitarian: it does not belong to some members of the group more than others. For some of the same reasons gamelan has become a beloved institution at many North American colleges and universities.69

Why has gamelan become a worldwide phenomenon, while other kinds of Indonesian music have not? This situation is a good example of Anna Tsing’s idea of “friction”: some kinds of music move easily and gain a foothold in new places, and others do not.70 In the case of gamelan the musical values of European and Euro-American listeners have garnered this music institutional support. Gamelan has been treated as a “classical” (or court) music by scholars; indeed, it has been researched since the 1920s, sometimes with the financial support of the Dutch government. As a court music with a long history, gamelan could be taken seriously in the West as a tradition analogous to European classical music. After Old Order Indonesia successfully exhibited gamelan at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, the Indonesian government sold 10 sets of gamelan instruments to colleges and universities in the United States. Though the sale was inspired by a need for hard currency, this gesture also supported the propagation of gamelan in academic institutions outside Indonesia.71

According to Sumarsam, a Javanese American ethnomusicologist, “the colonial legacy has brought about a complex society in which individuals’ and institutions’ viewpoints cannot be sorted in terms of a simple inside-outside dichotomy.”72 The various efforts that colonial and postcolonial governments made to establish, reestablish, or publicize musical traditions gave gamelan support within Indonesia but also made gamelan seem to outsiders like a tradition of central importance. The outsiders’ positive view then encouraged Indonesians to maintain that tradition. For instance, echoing the Exposition of 1889, the New Order regime continued to support gamelan as an emblem of Indonesia, sending Javanese and Balinese gamelan and dance to represent Indonesia at the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka.73 This action aimed to satisfyPage 42 → world opinion with a music that had proven recognition and appeal, as cultivated during the colonial period. In contrast, contemporary Indonesian popular music—much more popular than gamelan with listeners in today’s Indonesia—has struggled since the 1970s under changing regulations about what kinds of music and dance could be broadcast over government-controlled radio and television. As Indonesian government officials believed this less dignified music was unfit to represent Indonesia, it found little support for international visibility.74

In the widespread adoption of gamelan the institutional legacy of colonialism is still present. East Asian, European, and North American institutions have demonstrated a preference for a “classical” or courtly music over a popular one, for an established tradition over newer ones, and for music that seems like ritual over transparently commercial music. These preferences accord with the priorities imposed by Europeans and carried on by the postcolonial governments of Indonesia. Musicians’ choices to innovate or to preserve tradition and listeners’ choices about which music to prefer reflect contemporary circumstances, but they are rooted in many layers of practices and values from the past. These layers include what the music means and has meant to generations of people of many ethnicities, as well as the ways in which colonizers and colonized people have interacted to shape and reshape the tradition over time.75

The situation of gamelan in today’s world reveals that colonial relationships do not end when the colony becomes independent. The administration of any colony alters social and political norms, moving people around geographically and creating unequal power relations among them. After a colony breaks off the political relationship with a colonizer, the social and economic relationships created by colonialism often remain active. Even as they change, these relationships provide a network of connecting threads, shaping the pathways along which music moves.