1.4: The African Diaspora in the United States

- Page ID

- 172096

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Appropriation and Assimilation

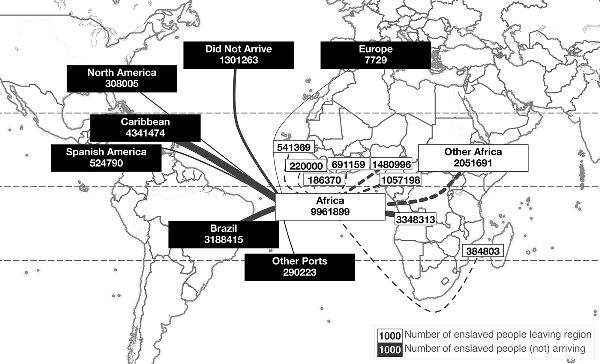

The music of the United States is the product of peoples in motion. From the beginning the colonies that would become the United States consisted of overlapping immigrant groups who moved into territories inhabited by Native American peoples. The earliest large groups of white colonists arrived from England, Scotland, and the Netherlands in 1607. African people arrived in North America more or less continuously between 1619 and the 1850s as a result of the slave trade, the largest forced migration in world history (fig. 3.1). Depending on their origins, resources, and the freedoms granted or denied them by law and custom, these groups lived under vastly unequal conditions. The forced labor of enslaved Africans became a mainstay of the economy in the colonies, and the social relations created by slavery shaped every aspect of US society, including music-making.1 The music African Americans created in the United States has played an extraordinary role in the musical life of the Americas and the world.

The practice of slavery in the colonies that would become the United States began as indentured servitude but evolved into a hereditary, permanent caste. Early in the 1600s, servitude was based not on skin color but on religion: people who had not been Christian before coming to America were judged to be slaves. Nonetheless, the practice of slavery hardened into a system based on race—the assignment of social distinction based on color or other elements of physical appearance, in this case white citizens’ unshakable conviction that brown-skinned people were inferior—and enforced by law. The concept of race has no basis in human biology, but as an imagined fact that has affected how people interact with one another, it has shaped ideas about music and the conditions in which music is performed.2

The history of African American music is difficult to reconstruct; almost none of this music was written down until the 1800s, so scholars have relied Page 69 →on eyewitness accounts, most of them by white observers. Nonetheless, the mixture of diasporas has made the United States what it is, so scholars have tried to learn all they can about how these musics came together. This chapter describes two musical products of African diaspora in the United States—the blues and spirituals—with an eye toward the ways in which the social circumstances shaped the development of African American traditions.

The Blues: Made in America

Scholars generally acknowledge that enslaved Africans brought their musical traditions to the United States. Historical records mention that some slave Page 70 →traders required Africans to bring their musical instruments with them. On slave ships traders used whips to force captives to sing and dance—a form of shipboard exercise that entertained the traders and “aired” the captives to prevent disease.3 Once in the United States, enslaved Africans continued to make music on African and European musical instruments. Many firsthand accounts from colonial America describe group dancing and singing on Sundays, as well as songs to accompany manual labor.4

After the Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, some slaveholders moved west and south, taking enslaved people with them to cotton plantations in Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Louisiana, and eventually Texas. Some of the musical instruments we associate with those parts of the rural southern United States closely resemble African traditional instruments. The banjo appears to be a version of the long-necked lutes played by itinerant minstrels in the West Sudanic Belt, the transitional savannah area between the Sahara Desert and Equatorial Africa that runs from Senegal and The Gambia through Mali, northern Ghana, Burkina Faso, and northern Nigeria. By contrast, one-stringed instruments, played with a slider against the string, are traditional in the music of central Africa: they are an antecedent of the slide guitar tradition in the southern United States. Another kind of one-stringed instrument is the “mouth bow,” which is plucked or strummed while held against the mouth. This instrument, played in the Appalachian and Ozark regions of the United States, is part of the musical traditions of Angola, Namibia, and southern East Africa.5 The presence of these instruments offers tangible evidence that Africans brought their own ways of music-making to the Americas.

Because slave owners bought and transported slaves at will, though, Africans typically could not stay together in family and community groups that maintained these traditions. The extent to which African ethnic groups were able to maintain contact among themselves in the Americas is debated by historians: there is some evidence that ethnic clusters persisted in some places, but most scholars describe the African experience in the Americas as one of profound dislocation for families and communities.6 Considering this disruption, some scholars have wondered about the possibility of survivals or retentions from African music—that is, whether some traits persisted from the traditional musics that Africans brought with them.7 In contrast, the music scholar Kofi Agawu argues that these terms imply too much passivity; rather, Africans and people of African descent actively guarded and preserved their musical heritage.8

Page 71 →What is certain is that Africans continued to develop and adapt their traditions in the Americas; they also initiated new musical traditions. The blues are an exemplary case. The blues are a tradition of solo singing, developed by African Americans in the United States in the mid- to late 1800s, that gives the effect of highly personal expression. Early blues often described hard work and sorrow, but they also treated broken relationships, money problems, and other topics—sometimes seriously and sometimes with a wry sense of humor. The lyrics are cast in the first person: “I’m leaving this morning with my clothes in my hand . . .”; “I didn’t think my baby would treat me this way. . . .” The first-person lyric does not mean the blues are autobiographical; rather, the singer creates a speaking persona and a vivid situation with which the listener can identify.9 Most melodic phrases start at a relatively high pitch and descend. In addition, the singer might use wavy or inexact intonation, producing an expressive and highly variable sound that may resemble a complaint, a wail, even a provocation. In early blues there might be just one accompanying instrument, often played by the singer: guitar, banjo, fiddle, mandolin, harmonica, or piano. As blues gained in popularity and record companies began issuing recordings, that simple accompaniment was often replaced with a small band.

The poetic form of the blues is a three-line verse: the first two lines have the same words, and then the third line is a conclusion with new words:

Lord, I’m a hard workin’ woman, and I work hard all the time

Lord, I’m a hard workin’ woman, and I work hard all the time

But it seem like my baby, Lord, he is dissatisfied.10

This verse form maps onto a musical structure, the “12-bar blues”: each line consists of four bars (units), each of which comprises four beats (time-units felt as pulses). This form can be repeated, bent, broken, or ignored as the musician wishes. The tempo is slow, and the rhythm has a characteristic “swing,” giving the listener the sense that there is an underlying pattern of long and short notes on each beat. The overall texture is not complicated. Often the instrument drops out, or simply keeps the beat while the singer sings one phrase, and then comes in with more interesting material after that phrase. This kind of musical back-and-forth is known as a pattern of call and response.11 Mississippi Matilda Powell’s “Hard Workin’ Woman” (example 3.1) is a blues composition that exemplifies all these features.

Gerhard Kubik is an ethnographer—that is, he seeks to record and analyze the practices of particular groups of people. For many years he has tried to understand the connection between African music and the African American blues tradition in the southern United States. Kubik traveled through Africa and made numerous field recordings; he then compared specific elements of those field recordings to the earliest existing recordings of the blues. Kubik was careful to note that there are limitations in this method: by comparing recordings made decades apart and continents away, one cannot determine a “family tree” for the blues. Music was not routinely recorded until the 20th century, so there is no way for us to hear precisely how the blues tradition developed during its early years. And certainly the recordings Kubik made in the 1960s cannot be “ancestors” of blues recordings from the 1920s! Rather, Kubik tried to identify characteristic elements of musical traditions—traits that might be preserved over time—that would suggest a kinship between those traditions. Like a family resemblance to a distant cousin, these traits hint at a relationship; but as we will see, there is also much in the blues that reflects their distinctly American origins.

Kubik’s research suggests that musical traits from two different parts of Africa contributed to the blues. One is an ancient lamenting song style from West Africa that was associated with work rhythms, which Kubik calls the “ancient Nigritic” style. These songs would be accompanied by the repetitive motions and sounds of manual labor, like the sound of the stones used for grinding grain. Kubik recorded example 3.2, sung by a person he identified only as “a Tikar woman,” in 1964 in central Cameroon.

The grinding tool that accompanies the song produces a “swinging” rhythm. The singer’s melody begins high and descends with each phrase, and the phrases are of roughly equal length. The words of this song, like those of typical early blues, are a lament and a work song: “If you don’t work you cannot Page 73 →eat. I am crying about my fate and my life.”12 Kubik identifies these features as survivals within the blues style. He compares the example from the Tikar woman in Cameroon with the blues singing of Mississippi Matilda Powell (example 3.1). Powell’s thin, breathy vocal quality also resembles that of the Tikar woman.

The other style Kubik identifies as a possible cousin of the blues is an Arabic-Islamic song style that developed among the people of the West Sudanic Belt, particularly the Hausa people of Nigeria and Niger. Unlike the ancient Nigritic style, the Arabic-Islamic song style was urban and cosmopolitan: it flourished around major cities and courts. This kind of music was made by a single person, accompanying himself on an instrument. As the singer was an entertainer who would move from place to place, this tradition consisted of solo songs that were not connected to community music-making. An example offered by Kubik is the song “Gogé,” performed by Adamou Meigogué Garoua, recorded in northern Cameroon in 1964 (example 3.3).

The distinctively raspy vocal style of this example sounds vehement and sometimes exclamatory, the words declaimed theatrically. Most of the phrases descend in pitch, and the singer’s voice often slides between pitches or moves quickly among ornamental notes. The combination of voice with instrument is also distinctive: during the sung phrase the fiddle is silent, but between phrases the fiddle comments with melodies of its own in a call-and-response pattern. We also hear in this song the characteristic “blue” notes (bent or pitch-altered notes) associated with blues.

Kubik compares Garoua’s song with a blues by Big Joe Williams, “Stack O’Dollars” (example 3.4), recorded in 1935 in Chicago.

As in the Garoua example, Williams uses his voice to make many different qualities of sound. Sometimes he speaks in a raspy voice; sometimes his melodyPage 74 → reaches up to become a wail. Throughout, he bends notes, glides between notes, and adds ornaments. The call and response between the singer and instruments is present here, too. For these reasons Kubik identifies a link between these elements of the Arabic-Islamic song style and the African American blues.

In short, Kubik finds it likely that musical traits from different groups of people, and different parts of Africa, contributed to the blues tradition in the United States. But the Arabic-Islamic and ancient Nigritic song styles were not like stable “ingredients” that simply mixed together to form the blues, nor were they handed down only among people who belonged to the ethnic groups from which these styles came. That is, blues were not a “heritage” music in this genealogical sense. During the slave trade, family and ethnic groups suffered disruption and dislocation. The migration of slave owners and the sale of enslaved people to distant regions meant that members of different African ethnic groups were mixed together and dispersed widely among European American communities. The blues were not cultivated only among West Sudanic or West African ethnic groups in the United States. So how did these elements of song traditions take root, or become localized, in their new environment?

In Kubik’s view the prominence of certain traits in blues is not explained by who brought these traits to the United States (heritage). Rather, these traits became widespread because they were useful and attractive to black people in the particular environment of the South in the 1800s; that is, this music spread as a tradition, passed from person to person.13 Musicians can learn both songs and techniques fairly quickly: when they hear something they like, they may imitate it and adopt it as their own. Kubik thinks there was a kind of selection process; for example, musical traditions involving drums were frequently suppressed by slave owners, so traditions without drums flourished. That blues could be performed by one person with any instrument that came to hand made it an inexpensive and mobile musical form that was hard to take away. Unlike louder forms of group singing and dancing, the blues were less likely to attract unwanted attention in an oppressive and controlled environment. Blues singers could use the themes of suffering, overwork, and loneliness derived from the ancient Nigritic style to describe their experiences and to speak for their communities. Furthermore, the 1890s saw the rise of Jim Crow laws, which limited economic and social opportunities for African Americans; but because slaveholders had exploited black people for entertainment as well as work, white Americans remained willing to accept African Americans as entertainers.14 In all these ways the blues had expressive and practical advantages.

Page 75 →Appropriation, Authenticity, and the Blues

The blues are much more than the sum of these African traits. Many aspects of the American context, including various audiences and commercial markets for the blues, were vital in shaping the history and content of this music. When black blues musicians traveled to perform in tent shows and vaudeville theaters (1890s–1920s), they found an audience of mixed ethnicities with an appetite for popular song. Soon white singers picked up this style of singing and the three-line form of the blues song. Composers of popular songs, many of them Jewish American, wrote blues and published them as sheet music (1910s). Many of these popular songs—some labeled as “blues,” some just incorporating aspects of the blues—were issued on commercial recordings (1920s).

In the 1930s and 1940s, folklorists—some sponsored by the US government—went looking for southern folklore and “rediscovered” the rural blues, which by then seemed utterly different from the widely known commercial forms of blues. Elvis Presley (1950s) and the popular singers of the British Invasion (1960s) not only took African American blues singers as their models but also recorded their songs, often without attributing them to the original songwriters.15 By the late 1960s the blues were recognized around the world as distinctively belonging to the United States. They were used in US public relations abroad and widely imitated.16 We have already seen in chapter 2 an instance in which the musical practice of a minority group becomes a symbol and a point of pride for the nation at large. (Recall that the “Hungarian” music for which Hungary is most famous is Romani music.) To extend Kubik’s line of thinking: the blues spread among people of many ethnicities because the style and themes of this music appealed to many musicians and audiences.

Yet, in the face of persistent social and economic inequality, one might wonder whether this kind of appropriation can happen on fair terms. Appropriation means taking something as one’s own. Musical “taking” is, of course, a special case: if someone adopts a musical style or idea, the person from whom it was adopted can still play the music that has been taken. For this reason musical appropriation is sometimes called borrowing, which has a less negative connotation. A more neutral-sounding term for the spreading of music is diffusion—an intermingling of substances resulting from the random motion and circulation of molecules, as in chemistry. As the metaphor of diffusion involves no human actors at all, just the movement of music from one group to another, this idea seems to attribute the movement of music to a Page 76 →natural process—like talking about globalization as a “flow” without saying who caused that flow. But appropriation is a purposeful choice, and a personal one: as we saw in the case of Liszt (chapter 2), the act of taking music as one’s own reflects the taker’s values and biases.

If we want to think about it in neutrally descriptive terms, we might say that the circulation of ideas is merely what has happened, and still happens, in the ebb and flow of music-making. Musicians have long taken sounds and ideas from others, repurposing or altering music to suit their own purposes. But appropriation can also mean theft. Cultural appropriation occurs when a member of a group that holds power takes intellectual property, artifacts, knowledge, or forms of expression from a group of people who have less power.17 Most definitions of cultural appropriation assume that “cultural” groups and their musical practices have clear and firm boundaries. They do not: music may be made differently even by members of the same group, and group allegiances are often hard to define. But people use the idea of cultural appropriation to address a real problem: if the powerful take music from the less powerful, what are the consequences? To put it bluntly: is this appropriation more like a complimentary form of imitation or more like a colonial extraction of resources?

One form of harm that can come about through cultural appropriation is that powerful people profit more from the music than do the less powerful people who made the music first. In the early days of the blues African American performers did earn money through in-person performance and recordings. Still, their earnings were modest. Recording and publishing companies often cheated musicians who lacked access to expert advice about contract and copyright law. Many media outlets preferred to play recordings by white musicians, further limiting black musicians’ opportunities to profit.18 During and after the 1960s, rock bands such as the Rolling Stones, Cream, and the Allman Brothers certainly reaped far greater monetary rewards from the blues than did the African American blues musicians whose songs they played. At the same time, the blues revival that spread the blues among Americans of other ethnicities increased professional opportunities for African Americans. Some musicians of this generation, such as B. B. King and Buddy Guy, attained considerable wealth and prestige, as well as a place in the spotlight. As the black blues musician Muddy Waters reportedly said of the Rolling Stones, “They stole my music but they gave me my name.”19

Cultural appropriation can also make practitioners of the appropriated music feel that they have been misrepresented. The revivalists’ attraction to the Page 77 →blues was based in part on insulting exoticist stereotypes about African Americans and their lives.20 In a 1998 history Leon Litwack wrote that “the men and women who played and sang the blues were mostly poor, propertyless, disreputable itinerants, many of them illiterate, many of them loners, many of them living on the edge.”21 This account describes African Americans as hapless, mysterious, and utterly different from other Americans who might encounter their music. These stereotypes emerge from long-standing categories of racist thinking that have been difficult to unseat. Historically, the advocates of segregation had justified their position by claiming that African Americans were weak, dependent, and incapable of progress, effectively relegating them to the enforced boundaries that slavery had created. These habits of thought persisted even as many white Americans embraced the blues, and they remain a key part of the image of the blues.

Instead of seeing the blues as an art form requiring expertise, some observers have viewed the blues as the natural product of African Americans’ mysterious lifestyle. Eric Clapton, the lead guitarist of Cream, noted that it had taken him “a great deal of studying and discipline” to learn the blues, whereas “for a black guy from Mississippi, it seems to be what they do when they open their mouth—without even thinking.”22 The stereotype operating here makes a hard distinction between folkloric music (handed down by tradition, eternally the same) and commercial music (sold in a marketplace, constantly changing). As we saw in chapter 1, the idea of the “modern” had been used to draw distinctions between non-Europeans and Europeans, and between the savage and the civilized.23 Clapton’s statement set his own creativity apart from that of African Americans, failing to acknowledge the individual creative effort of black blues artists.

Some people have argued that cultural appropriation is harmful because they want to preserve the authentic musical practice—for instance, recovering the blues as they were long ago rather than allowing for changes in the tradition. Authenticity is perceived closeness to an original source; judgments of authenticity are made with the aim of recovering that real or imaginary original. People who seek authentic blues take pleasure in a folk experience they have imagined for themselves as rural, untouched by commerce, and laden with suffering: they hope to find a true point of origin where the music first sprang into existence. Yet this argument is based less on historical facts than on present-day values, which emphasize distinctions between folk and commercial music and between origins and current uses. Authenticity is not a property of the blues; rather, it is a story that people tell about the music and Page 78 →its makers, a story that emphasizes heritage and the difference between “them” and “us.”24

In seeking authenticity, people often treat “cultures” as clearly delimited from each other, and they look for a source that is identifiably from only one group, not mixed or “hybrid.” The problem with this kind of thinking is that reality is more complicated. As best we can know it from the limited documentation that survives, the history of the blues does not support a clear distinction between folk and commercial music. Far from untouched by commerce, African American artists took advantage of opportunities to make money through music. Oral histories of the rural blues suggest that some blues musicians traveled from place to place to earn a living as entertainers, acquiring new material and making innovations in their performances along the way.25 The blues became known to the wider public in the 1900s and 1910s, as African American musicians performed the blues and other music professionally in theaters and circus sideshows. Blues musicians heard, and sometimes imitated, the vaudeville performances.26 When the blues were “discovered” by record companies—and of course one can hardly call it a discovery, as the music was already flourishing—African American performers willingly recorded their music for commercial markets.27 These recordings, in turn, fostered a new generation of blues musicians in the South, who learned to play from the recordings instead of from local musicians.28 In one way or another most musicians tailor their music to the demands of audiences, and African American musicians are no exception.29 Here we see a limitation of Kubik’s theory or of any theory that tries to define a thing by going back to its origins. Some elements of African music came together in the blues, but the context of traveling shows and commercialism in the United States was also an essential factor in the music’s development.

The mistaken focus on authenticity at the expense of other musical values reifies music—that is, makes it into an object rather than an activity. When blues became not just a manner of performance, but also a folk artifact to be recorded for posterity or a musical form to be copied, it became more like an object to its borrowers, losing the flexibility of live performance and changeable tradition.30 Once that happens, there is a risk that all performances will be measured against that “original” version. Holding the original as the highest standard disincentivizes creative development of the tradition.

Focusing on authenticity can also assign to music-makers a rigid set of group characteristics that differentiate them from other groups. The belief that all members of a certain group have particular inherent attributes is called Page 79 →essentialism: it is a way of making stereotypes seem truthful by saying they are a permanent part of the people they represent. The blues were especially attractive to white musicians in the 1960s who wanted to seem oppositional to the social status quo. But by emphasizing the authenticity of the tradition, they relegated African Americans to being part of history rather than part of the present day, as Clapton did. They essentialized African Americans as the unchanging folk source of the music and named themselves as the innovators.

Claims about authenticity are not only produced by white people who want to reify the blues. They have also been used by people who want to protect African American ownership of the blues tradition. This line of thinking has sometimes been called strategic essentialism: a disempowered people’s temporary use of stereotypes about themselves to promote their own interests—in this case, to guard a valued heritage against a specific act of appropriation.31 In the early 1960s, a volatile period in the civil rights movement, the critic Amiri Baraka wrote a searing critique titled “The Great Music Robbery” in which he addressed white appropriations of African American music. He objected because white musicians were earning so much profit and praise for playing black music but also because the blues represented specific African American experiences. Baraka went so far as to call the idea of a white blues singer a “violent contradiction of terms”: not because the blues were a genetic inheritance of black people but because the common experience of discrimination, reflected in the blues, bound black people together as a group.32 The absorption of black music into American music, explained Baraka, changed the meaning of black music and even felt like erasure of black people and their experiences. “There can be no inclusion as ‘Americans’ without full equality, and no legitimate disappearance of black music into the covering sobriquet ‘American,’ without consistent recognition of the history, tradition, and current needs of the black majority, its culture, and its creations.”33

At the same time, though, saying that black people are fundamentally different from other Americans reinforces that social separateness and the stereotypes that support it. The music scholar Ronald Radano has argued that Baraka’s criticism essentializes African Americans by assuming they all share similar origins and experiences. Telling the story of black music as if it were entirely separate from white music not only misrepresents history but also reinforces a false belief in fundamental racial differences—and this belief can then be used to justify continuing discrimination.34 Baraka did recognize the danger of essentialism: in a different essay he emphasized that committed musicians of any color could learn the “attitudes that produced the music as a Page 80 →profound expression of human feelings.”35 This statement means that African American music is an open tradition in which people of various ethnic origins might learn to participate, if they are willing to try to understand black musicians’ perspectives and experiences.

Thus, the objections to cultural appropriation boil down to economic exploitation and disrespectful representation.36 One could try to respond by discouraging appropriation. Yet people who use the charge of cultural appropriation as an effort to prevent traditions from mixing can also cause harm, perpetuating essentialist stereotypes. Thinking of the blues as an unchanging essence encourages white audiences to ignore African Americans’ further development of that tradition—or of other traditions. Worse, thinking of African Americans as people who only produce blues or spirituals unjustly limits their artistic freedom. In the words of the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, “talk of authenticity now just amounts to telling other people what they ought to value in their own traditions.”37 Musical appropriation across lines of social power seems generally to have this ambivalent quality: it can cause real harm to real people, yet trying to prevent appropriation can also cause trouble by encouraging inflexible and stereotypical thinking about groups and differences. This dilemma is built into life in the United States because of the violent and unequal circumstances by which the nation developed. The particulars of any musical borrowing among peoples in the United States may reinforce that violence, or work against it, or try to find a way past it; but it is always there to be grappled with.38

The Spiritual: Mutual Influence and Assimilation

Both European Americans and African Americans have nurtured traditions of religious singing, or “spiritual song.” Whereas some of the African American music used for entertainment developed separately from European American traditions, religion offered a point of contact between black people and white. During the 1600s and 1700s some groups made efforts to convert enslaved people to Christianity. In the North enslaved people were often considered part of the household, and they were encouraged to sing psalms and hymns as part of prayer services. Missionaries visiting the South pressed for conversion, but slaveholders decided whether and what to teach the enslaved people under their control. Generally, African Americans in the South received less religious Page 81 →instruction than their northern counterparts, in part because of a fear that literacy would empower them. The 1700s saw the rise of African American churches in both South and North. In the North these churches grew and developed their own collections of hymns, but southern whites feared that black churches were aiding in the organization of slave rebellion, so they disbanded them.39 Some scholars have speculated that pervasive segregation by race in the southern United States helped to preserve African American musical practices.

From the 1720s through the 1800s people in the United States participated in several waves of religious fervor, commonly known as the Great Awakening. During the Second Great Awakening (1800–1840s) itinerant evangelical preachers defied conservative Protestant slaveholders by hosting camp meetings, lively outdoor worship experiences that might last a week, attended by thousands of people. These evangelical meetings encouraged excited and emotional expressions of faith instead of rehearsing old-fashioned, carefully written sermons; this value harmonized with already existing African American musical practices. Camp meetings were interracial events, typically attended by black and white alike, even by enslaved people, and they were sometimes led by African American preachers. The degree of social mixing across racial lines would vary from place to place, and sometimes African Americans had to stand or sit separately from white participants. Nonetheless, the religious practice of the camp meeting offered an opportunity for European Americans and African Americans to find common ground in the language and practice of Christianity and taught some European Americans to regard African Americans as real people with souls and spiritual lives.40

Singing of religious songs played a prominent role in these Christian camp meetings. Observers recorded that African American attendees contributed “boisterous” singing at the meetings and often stayed up all night singing hymns after other attendees had gone to bed.41 A Methodist preacher, John F. Watson, was concerned because the style of this worship differed substantially from white Protestants’ musical renditions and did not meet their standards of respectfulness: “In the blacks’ quarter, the coloured people get together, and sing for hours together, short scraps of disjointed affirmations, pledges, or prayers, lengthened out with long repetition choruses. These are all sung in the merry chorus-manner of the southern harvest field, or husking-frolic method, of the slave blacks. . . . With every word so sung, they have a sinking of one or other leg of the body alternately; producing an audible sound of the feet at Page 82 →every step. . . . What in the name of religion, can countenance or tolerate such gross perversions of true religion!”42 Watson complained that African Americans were using words and music that were not officially sanctioned by any religious denomination. Another frequent complaint was that African Americans performed worship music with energetic dancing. African Americans differentiated the kind of body movement they would perform at a “shout” (worship) from the kind of movement they would consider dancing, but to white outsiders their bodily engagement in worship seemed disrespectful. Even as white listeners marveled at a kind of singing that was strange to their ears, coming together to sing helped African Americans identify themselves as a community, both within and out of earshot of European Americans.

Watson’s description of “short scraps” helps us understand how African Americans’ Christian camp meeting music worked. Though many had become familiar with the words and music of European American Christian hymnbooks, this music was used from memory and only in part. The worship leader would often sing a line, either from a hymn or improvised on the spot, and have the congregation repeat it, alternating the call of the leader with the response of the congregation. A similar practice, called lining-out, had been used in the British Isles before it was exported to the colonies. At the same time, this practice of alternating lines was also consistent with the call-and-response form that African Americans used in work songs. In the British practice lining-out tended to stick closely to the words in a hymnbook: it was a way of teaching illiterate congregants biblical stories by rote. In contrast, African Americans freely combined lines of Christian hymns with improvised words of praise. The leader could move from one idea to another, and the congregation would follow.43 An observer in the 1880s wrote: “When the minister gave out his own version of the Psalm, the choir commenced singing so rapidly that the original tune absolutely ceased to exist—in fact, the fine old psalm tune became thoroughly transformed into a kind of negro melody; and so sudden was the transformation, by accelerating the time, for a moment, I fancied that not only the choir but the little congregation intended to get up a dance as part of the service.”44 Frequently, African Americans added memorized choruses from other hymns that were well known among the congregation as the spirit moved the leader, even if this resulted in mixing of the original hymn texts or entirely new statements of faith.

Scholars typically refer to this genre of African American singing as the folk spiritual. The audio recordings we have of folk spirituals were made long after the 19th-century camp meetings. Researchers have read eyewitness Page 83 →accounts, listened to the later recordings, and made their best guesses about how African American spirituals might have sounded in that time. The written historical sources can be compared to living people’s knowledge of the spiritual. As the singer and scholar Bernice Johnson Reagon has said of her childhood during and after the Second World War, “As I grew up in a rural African American community in Southwest Georgia, the songs were everywhere.”45

African American folk spirituals were sung in groups, generally with no instrumental accompaniment. The words of these songs focus on themes from the Bible, with particular attention to stories of liberation. These included Daniel’s deliverance from the lion’s den; the journey of the Hebrew people from their captivity in Egypt to freedom; and the figure of Jesus as a liberator from sin. Frequent allusions to being a people chosen by God assert a sense of self-worth and confidence in a better future.46 Though the spirituals have sometimes been called “sorrow songs,” they express a variety of emotions, from longing to rejoicing.

In example 3.5 the Blue Spring Missionary Baptist Association of southwest Georgia blends improvised preaching and improvised singing.47

The congregation in this recording sings ecstatically in answer to the preacher’s message. The leader speaks or sings a phrase, and the congregation speaks or sings in return. Not all of the singers in this congregation are “in sync.” Some start just a little before others as they decide in the moment what to sing together by listening carefully to each other. The ethnomusicologist Charles Keil has argued that this slightly “out of time” feeling gives this music its dynamic and engaging qualities.48 Each singer has a great deal of freedom to sing the music in her or his own way: some offer embellishments around the main pitch or create harmonies.

The United Southern Prayer Band of Baltimore’s rendition of “Give Me Jesus” (example 3.6) is congregational spiritual singing in the African American tradition. Like the preceding example, this music was recorded in the Page 84 →1980s, but it includes many of the features scholars believe were part of the tradition from long ago.

It is a joyful and participatory style of singing. One has the sense that the congregation is spontaneously moved to involvement by lifting their voices, stomping their feet, and clapping their hands. That the song is repetitive means that everyone can participate, whether or not they knew the song beforehand; this kind of repetition was characteristic of camp-meeting songs.49

We might compare this rendition of “Give Me Jesus” to a recording of a white congregation in Kentucky singing the hymn “Guide Me O Thou Great Jehovah” (example 3.7). This recording illustrates the practice of lining out a hymn: the leader sings each line of the hymn, and the congregation answers in a call-and-response pattern. In this and other ways this singing is very like the above examples from African American congregations.

We hear a deep engagement in worship and repetition that allows for broad participation, as well as a heterophonic singing style in which participants are free to add ornaments or harmonize. Note, though, that we hear no foot-stomping or hand-clapping; this performance is more restrained physically.

Scholars have historically had difficulty sorting out how the mutual resemblance between white and black spiritual song styles developed. Beginning in the 1930s, some suggested that African Americans took British American tunes for lining-out and “Africanized” them—much in the same way that Romungro musicians took Hungarian folk melodies and approached them in their own special style.50 This theory pained African Americans: in Reagon’s words, “Leading scholars claiming an objective, scientific method of research and Page 85 →analysis studied our work and ways of living and declared us incapable of original creativity.”51 But there is growing agreement among scholars today that most of the tunes did not come from British traditions: African Americans used ideas from Christianity but made their own songs about those ideas and performed them in their own ways.

It is reasonable to believe that the spiritual is a truly American creation and that contact between black Americans and white Americans shaped the music of both populations.52 The melodies and the freely improvised and recombined words we hear in this kind of spiritual singing are consistent with what we know about older African American practices. African Americans incorporated Christian religious ideas and found lining-out compatible with their own call-and-response singing. As testified to by Watson’s complaints, this practice seems to have had a meaningful influence on white singing, especially in the southern United States, through camp meetings.

The Spiritual and Assimilation

The folk spiritual is still a living tradition. Yet, like most living traditions, it has engendered offshoots and been borrowed and transformed in a variety of ways: these transformations are also part of the continuing story of how music moves. In the Civil War era spirituals were used by abolitionists as propaganda for their cause: these songs showcased the suffering of African Americans under slavery. On one hand, musically minded white listeners could find common ground with black singers in appreciation of the spiritual. On the other hand, the danger of essentialism arises here again: images of suffering African Americans were sometimes used to affirm white superiority and racism.53 This misperception was also a highly conspicuous element of the popular entertainment called minstrelsy. Featuring skits and musical numbers, minstrel shows depicted black people as comical, pathetic, the butt of every joke. African American intellectuals objected to this kind of portrayal and looked for ways to counteract it. They aimed to present African Americans in a manner that would gain respect among European Americans, especially among the educated Protestants of the North who might be sympathetic to the cause of free African Americans.

As the ethnomusicologist Sandra Graham has described it in her book, Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry, the African AmericanPage 86 → colleges founded after the Civil War (now usually known as “historically black colleges and universities,” or HBCUs) worked hard to change public perceptions of black people. Music was one tool for change. H. H. Wright, dean of the Fisk Freed Colored School (now Fisk University) in Nashville, Tennessee, recalled that “there was a strong sentiment among the colored people to get as far away as possible from all those customs which reminded them of slavery.” Wright reported that the students “would sing only ‘white’ songs.”54 Ella Sheppard (1851–1914), assistant director and founding member of the choir at Fisk, explained that “the slave songs were never used by us then in public. They were associated with slavery and the dark past, and represented the things to be forgotten. Then, too, they were sacred to our parents, who used them in their religious worship.”55 But with the encouragement of their music teacher, the white missionary George White, the Fisk choir began to sing a few spirituals on campus alongside their repertoire of hymns, popular parlor songs such as “Home Sweet Home,” and a few selections of European classical music.

That the Fisk choir sang primarily “white songs” is an example of assimilation: people within a minority or less powerful group changing their behavior to be more like a dominant group. We might think of assimilation as a companion concept to appropriation: it emerges from contact between groups who have unequal authority. By singing music associated with white people, the Fisk students sought to distance themselves from perceptions about black people as slaves. Many white people associated cultivated choral music with social privilege and respect: the Fisk students surely hoped that this kind of singing would mark them as educated people who belonged in polite society.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers made their first concert tour under the direction of George White in 1871 to raise funds for a building project at Fisk. They sang in churches and theaters alike, and their program consisted of the “white songs” they had customarily performed. In 1872 they added a few spirituals to their repertoire, and these quickly became so popular that they came to dominate the Jubilee Singers’ concert programs. Yet the spirituals were not sung as they had been in worship. The melodies were made regular in a way that conformed to the musical tastes of middle- and upper-class white people. Some songs were sung as solos or in unison, but some were set in four-part harmony, a technique borrowed from European music. In this style individual singers had fewer opportunities to improvise: one description of the Jubilee Singers praised their “precise unison.” Yet they did preserve some of the rhythmic features of the spiritual, such as accented notes placed off the beat, that white Page 87 →listeners found surprising.56 These assimilated versions of folk spirituals are called concert spirituals.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers were recorded early in the twentieth century; they probably sounded different then than in the 1870s, but this recording of “Deep River” still offers us some insight (example 3.8).

In this example we hear four-part harmony and a very smooth style of vocal delivery. There is no spontaneity or call and response in this music, as one might hear in the folk spiritual. Instead, “Deep River” is presented in a choral style that reflects the European ideals of precision and harmony.

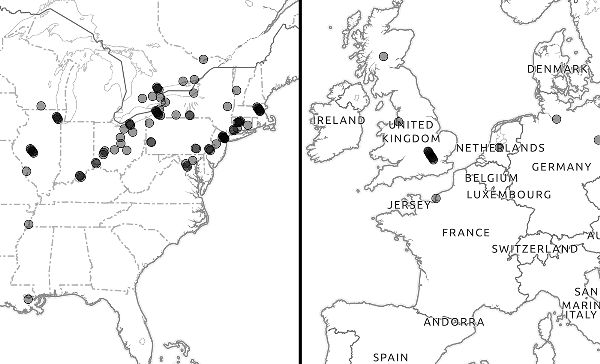

Over the course of six and a half years the Jubilee Singers raised $150,000 for Fisk, a staggering sum. (The map in fig. 3.2 shows many of their tour stops.) On the heels of this success the Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School (now Hampton University) and the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers (now Tuskegee University) soon founded their own groups of Jubilee Singers, aided by published sheet music of the Fisk group’s songs. The printed versions further altered the songs: they were written down according to norms of Western classical notation, in major and minor keys, even though in performance these melodies did not entirely conform to those keys.57

Graham has called the concert spiritual an act of “translation”: an intentional transformation that made the spiritual understandable and valuable to white audiences.58 White audiences could imagine that they were hearing the reality of the plantation, and the spirituals excited a sense of exoticism. One observer cited the choir’s “wild, delicious” sound; another delighted in the “strange and weird” music that recalled the harsh conditions under which African Americans survived.59 At the same time, the sound and the social aspiration of the concert spiritual were shaped by the institutions of higher education that sponsored them. The idea that African Americans needed to accommodate themselves to white norms in order to win respect reflected a sad reality of the day; this, more than anything else, shaped the sound of the concert spiritual. These performances succeeded in winning a great deal of praise and money from white listeners, though this affirmation was accompanied by a sense of exotic difference.60

In the early 1900s the spiritual became an increasingly popular source for Page 88 →choral pieces and songs to be presented in the format associated with a classical music concert. Harry T. Burleigh was part of the generation of African Americans born after Emancipation. A composer and singer, he studied at the National Conservatory of Music in New York. He composed many of his own songs in the art music tradition, but his arrangements of spirituals circulated more widely, and he was a key figure in developing interest in the concert spiritual among classically trained musicians. During the Harlem Renaissance (ca. 1917–35) artists such as Langston Hughes, Jessie Fauset, Duke Ellington, Roland Hayes, Paul Robeson, William Grant Still, Augusta Savage, and Hall Johnson focused on the creation of a positive African American identity through the arts.61 Part of their purpose was to find a less folksy, more modern expression of identity that they hoped would engender respect for black people among their white peers. Literacy had long been withheld from black people, so they wrote. Acknowledgment of their music as art had been withheld, so they composed.62

The Harlem Renaissance brought the concert spiritual, sometimes also called the “neospiritual,” into the spotlight again. Musicians began performing Page 89 →concert spirituals as solo songs with piano accompaniment. The tradition of performing spirituals in this way comes from the classical music genre of the art song—a formal and prestigious kind of classical performance. Songs of this type were popular in the United States in the 1800s because they could easily be performed in middle-class homes.

A strong proponent of the concert spiritual was Paul Robeson. He performed spirituals in concert alongside other music representing the peoples of the world, with the purpose of claiming equal respect for all. The arrangement of “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” for voice and piano we hear in example 3.9 was made by Lawrence Brown. Brown regularized the melody into orderly phrases with an unobtrusive accompaniment of simple chords. Robeson adopted some elements of dialect—singing, for example, “chile” for “child”—which was a characteristic marker of the concert spiritual at this time. Still, he projected his voice in the manner expected in classical music performance. This kind of performance contradicted the ideas about African Americans that were expressed in minstrel shows: the concert spiritual presented African American music as equal to, and similar to, European classical music.

The concert spiritual was controversial, even among African Americans who were committed to improving their social status through the arts. Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960), an anthropologist, folklorist, and writer who took part in the Harlem Renaissance, believed that only the spontaneous folk spirituals were authentic. She saw the concert spiritual as artificial, restrictive, and not really African American any more: “These neo-spirituals are the outgrowth of glee clubs. Fisk University boasts perhaps the oldest and certainly the most famous of these. They have spread their interpretation over America and Europe. . . . There has not been one genuine spiritual presented. To begin with, Negro spirituals are not solo or quartette material. The jagged harmony is what makes it, and it ceases to be what it was when this is absent. Neither can any group be trained to reproduce it. Its truth dies under training like flowers under hot water.”63 Intellectuals like Hurston questioned the practice of assimilation. They valued new economic and educational opportunities, but they were also looking for the best ways to preserve their traditions. Hurston felt strongly that Page 90 →the concert spiritual was a kind of domestication, making the spiritual easier for white people to understand while removing some of its essential features. This kind of adaptation changes the appropriated music into something new; and if the original music is beloved, this transformation can cause distress for those who love it. The problem of authenticity arises here again: some African Americans wondered if keeping a strict separation from European traditions was the best way to keep valued parts of their tradition alive.

The concert spiritual has crossed racial and national lines. Today, many church, community, and college choirs of varying ethnicities sing concert spirituals all over the world. Sometimes they imitate African American vernacular English, but often the language has been transformed into a more standard version of American English. Most characteristic of today’s concert spiritual, regardless of the racial identity of the singers, is a crisp precision of delivery.64 In this recording of “Wade in the Water,” sung by the Howard University Choir (example 3.10), you hear a meticulous choral sound: as in European classical choral music, a conductor coordinates the performance.

This music also lacks the spontaneity of the folk spiritual tradition. Any bodily motion (swaying, clapping) is either organized (everyone doing it together) or suppressed altogether. In these ways the concert spiritual has been distanced from African American folk approaches to performance. Even so, this concert spiritual retains from the African American tradition imagery of enslavement, escape through the water, and difficult journeying.

As a living musical tradition the spiritual has proved to be a music of extraordinary versatility, inspiring musicians of many traditions. It has also continued to be a valuable tool for those who choose to assimilate. The first female African American composer to win recognition in the classical music world, Florence Price (1887–1953), was conservatory-trained and framed her work within the Euro-American concert music (“classical”) tradition. She composed symphonies and other works for large ensemble, some piano music, and many songs. Her Black Fantasy (Fantasie nègre, example 3.11), composed for solo piano in 1929, is an arrangement of the spiritual “Sinner, Please Don’t Let This Harvest Pass.”

But at first it is not recognizable as such. We hear a stormy and passionate introduction that uses techniques borrowed from the European classical composers Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. (Recalling that Liszt appropriated others’ music, we might notice that all music is subject to reuse and further appropriation.) Only after that introduction is the spiritual melody heard (timepoint 0:58), but it is still decorated by the techniques Chopin used to ornament a songlike melody. This music is difficult to play: it reflects the virtuosic tradition of 19th-century piano music.

Through Black Fantasy and other works, Price sought to bridge the gap between African American traditions and the European American classical tradition. The difficulty of the work and its resemblance to classical piano works made a bid for respect and inclusion in that tradition, even as the spiritual melody offered content new to that tradition. In Price’s day most white Americans still had not thought of African American music as an art form but only as a kind of folk practice that did not require training, effort, or creativity. Price’s music demolishes that distinction, bringing ideas from African American music into the classical music tradition and insisting that this, too, is art.65

Troubled Water (1967), a piano piece composed by Margaret Bonds (1913–1972), continued the tradition of using spirituals to bridge traditions. Bonds’s music blurs the lines among different genres of music more completely, accompanying the spiritual melody with elements from classical music and jazz. Troubled Water (example 3.12) is a concert piece for piano, based on the spiritual “Wade in the Water.”

The piece has three main sections and a coda (a brief ending section). It begins with an ostinato (a repeated pattern) in the bass, a feature that frequently appeared in jazz piano performances of that era. The ostinato continues throughout the first and third sections of the piece, underneath a statement of the “Wade in the Water” melody that is harmonized in jazz style. When we hear the melody again in the contrasting middle section of the piece (from timepointPage 92 → 1:37 to 2:49), the accompaniment makes reference to classical piano works that represent water through rippling cascades of notes—especially Claude Debussy’s “Reflections in the Water” from Images. The third section of Bonds’s piece returns to the ostinato, and it is like the first section, though it also reintroduces some of the rippling water ideas near the end of the section. Troubled Water closes with a forceful statement of the spiritual melody.

In our day the blending of traditions is commonplace and usually intentional: the composer makes choices about how to express herself not only on the basis of tradition (what has been handed down to her by teachers or kin) but also by how she wants to be perceived and what she wants to represent. As Margaret Bonds and Florence Price sought entry into the classical music world, they could have chosen to assimilate completely, abandoning the musical markers associated with African American music. Instead, African American music became a resource for them and a point of pride that distinguished their music from others’. This piano music reflects the paradoxical views of the Harlem Renaissance: though black artists might choose to assimilate to improve their standing in a white-dominated country, they also continued to respect and cultivate the traditions associated with black Americans.

The relationships created by the scattering of people through diaspora are multifaceted and durable, involving many kinds of interaction and mutual influence. As individual American musicians make their particular musical choices, they act within or against racial identities defined by America’s colonial and diasporic history. Although the concept of race has no basis in science, race has often been treated as a social fact that defines or limits artistic heritage and community membership. Nevertheless, it is easy to see that in the United States musical traditions have become intertwined, with borrowings in many directions. In the experiences of the African American and Romani diasporas we can see many instances of the troubled and violent relations between diasporic minorities and their majority neighbors. At the same time, we can recognize the musical relationships created by diaspora as complex and significant forces that have shaped the development of music in countless ways. Once we have observed how these relationships work, we might use words like heritage and tradition with caution, for music is not only “handed down” within a family or other group, but also “handed around” through appropriation, assimilation, and other borrowing practices. These practices are not an exception: they are a typical part of how music moves.