9.5: Warriors or Lawyers?

- Page ID

- 135182

Rather, the main activity of this Kamakura “warrior government” – which we might liken to the hegemon of the Spring and Autumn period – was to create and manage a vigorous legal system. As historian Jeffrey Mass explains,

Throughout the Kamakura period the central concern of the Bakufu was to balance the interests of the traditional aristocracy in Kyoto with the interests of the rising class of warriors in the provinces. The judicial system that resulted became the foundation upon which the Bakufu established its ascendency.

When the Genpei War ended, Yoritomo needed to do three things: stop the fighting throughout the islands, reward his followers even as he reigned them in, and figure out a working relationship with the bureaucracy in the capital. He came up with two lasting solutions.

First, Yoritomo created a dyarchy, or “bipolar administration.” The court continued to manage the lands and taxpayers that fell under the centralized ritsuryo system; and the court and its members also continued to manage the lands and people of the estate system, that is, the rice rights owed to courtiers and temples. But in order to guarantee those rights, Kamakura put military men in charge of estates as stewards (jitō). Its main business became managing those stewards, its vassals, and resolving disputes that involved them. So, the second major innovation was a “vigorous judicial system.”6

Initially, while Kamakura controlled most of the Kantō plain, the imperial court still controlled the Kinai and other parts of Japan. But in 1221, the emperor Go-Toba tried to overturn the power of Kamakura. He was soundly beaten, and the shogunate (bakufu) was strengthened, so that the Kamakura vassals who had supported the bakufu were posted as stewards all over. They were selected as a reward for supporting the shogunate. Their job was to keep the peace, collect taxes, and serve in the army as needed. They checked military rivals and assured sufficient peace that temples, shrines, and aristocrats who cooperated could continue to collect income from their estates. The Kamakura stewards carried out police and judicial functions on the estates, collected the rents, and forwarded them to the owners of the various shiki rights. In return, they were granted shiki themselves as payment.

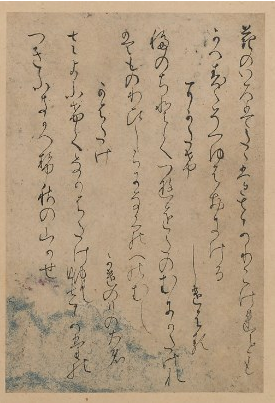

A further complication is that after Yoritomo died, the shoguns themselves became puppets managed by the Hōjō regents. These were Yoritomo’s widow Masako and her family, who held key posts in Kamakura. Since the emperor was still theoretically the top authority, this means that power was doubly removed from authority. And, there is yet a further complication. When we read the Kamakura lawsuits, they deal only with the rights to various kinds of product. The Hei’an-based administration dealt with a few murder and rape cases according to the central law code, but basically, regulations were set and justice was carried out at a very local level. Holding the right/obligation to manage disputes was in fact another kind of shiki right, and those rights could be divided for any given plot of land. Cultivators, a steward, and patrons at the capital could all hold rights in the same shōen estate (though not always) and cultivators also hold their own cultivation-shiki. In this network of various rights and obligations pertaining to one estate, the laws are issued by the holder of the highest (in terms of social status) shiki, often religious institutions or sometimes the imperial figures. So, a temple or imperial patron or even the village itself might issue regulations or send out agents to catch a thief. If there was also a steward, adjudication occurred at the bakufu level.7 Kamakura never created uniform laws. Rather, it tried to uphold the customary practices, rights, and relationships of each area.

Kamakura presents the paradox of a warrior government that mainly operated through a legal system. Not only that, but Yoritomo, his heirs and the Hōjō regents, never tried to expand their jurisdiction or their power. Quite the contrary: in the early years a few disputes involving only shōen were brought to Kamakura, but the bakufu court would not hear them – it heard only cases that involved its own vassals serving as stewards, or their police force. Its reputation as a fair court was so good that estate proprietors who should have appealed to Kyoto sometimes forced their suits on the bakufu courts. Not only did Kamakura not try to extend its power into the areas traditionally managed by the court, but it also minimized its interference in relations among its own vassals, encouraging them to work disputes out for themselves. Jeffrey Mass puzzles over the great inconveniences caused by the fact that the Kamakura government, when it appointed a steward, gave him the document proving his rights over the land, but did not keep a copy. Why would a government that works by examining pieces of paper and issuing paper decisions not keep copies of its own documents? But since Mass shows very clearly the reluctance of Kamakura to increase its jurisdiction, I think that refusing to keep the kind of paper record characteristic of a centralized, bureaucratic government makes perfect sense. Qin had undermined its popular support by trying to make reality match the paperwork. Kamakura judged cases only based on what the disputants brought forward.

Kamakura would not take complaints directed against it by its own vassals; nor would it take action against anyone of its own accord; it would only adjudicate disputes between stewards and other vassals, or between landholders of other kinds and stewards, or complaints brought by commoners against stewards. Further, if litigants called to Kamakura for a lawsuit did not come, the only response of the warrior government was to call them again, and again. The military governor who served the subpoena was responsible for bringing the defendant to court, but often this simply did not happen, and the worst punishment a steward faced for avoiding court was losing his job. In one case, this step – a judgement against a person who was not present – was taken only after seven repeated subpoenas. They never sent armed men to bring people in. This warrior government was very reluctant to use force.

Proud of their military accomplishments, the Kamakura samurai saw themselves as preserving peace and stability in balance with the larger, very old, and divine rulership of the royal family and courtiers. Mass points out the contrast with feudal Europe. There, although lords and vassals indeed took disputes to one court or another, the oaths and words of witnesses outweighed documentation, and only a royal edict had the final word. “Resort to the battlefield was never far from the minds of litigants.” By contrast, Mass writes, the Kamakura bakufu “had all but outlawed war.” If legal settlement was violated a second time, the two parties in the dispute return to the Kamakura court. They did not fight it out with their swords and bows.

For 150 years after the Taira uprising, many factors – revulsion against the violence it had brought; a sense of the benefits of the complex, divided property arrangements of Hei’an; respect for the court with its emperor descended from the Sun Goddess Amaterasu; transfer of this deference to the Kamakura lords; and a preference for peaceful arrangements for sharing the fruits of land and labor – all meant that a warrior government ruled mainly through careful legal processes based on documentary evidence.