9.4: Whence Came the Samurai?

- Page ID

- 135141

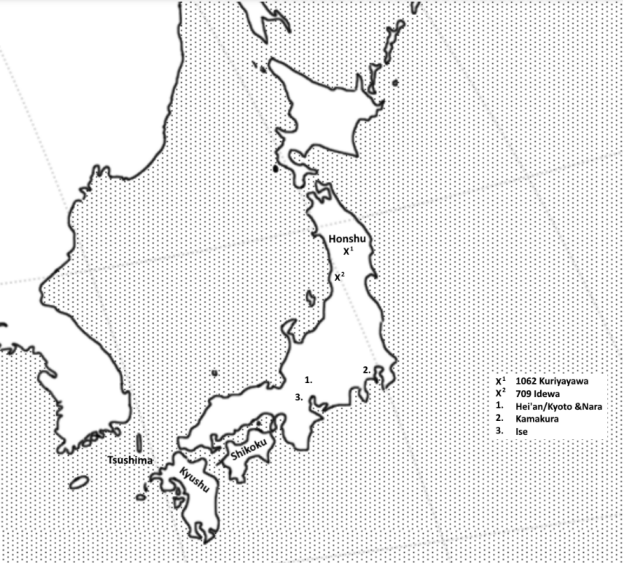

In the classical Hei’an world, warriors had no place among the elite. Where did the samurai come from? There is still a lot of scholarly debate about that. Court aristocrats and bureaucrats had employed professional fighters successfully throughout the Hei’an period, once the conscript army set up by the Taika Reforms as part of bureaucratic government had failed. Commanders had employed experienced fighting men on the northeastern frontier, and rulers had used career soldiers for routine patrol, criminal investigations, pursuit and arrest of criminals, and suppression of banditry. In and around the capital, a special police agency oversaw such organized state violence. Aristocrats had hired experienced military men to guard shōen property, punish enemies, and keep the peace. The abbots of Buddhist temples, too, developed their own guards of armed monks to protect their lands and rights.

For many generations, the court elite kept these warrior forces under control with a mixture of bribery, divided control, and ideology. Most obviously, it was not in warriors’ interests to undermine the system that employed them. Any individual soldier who seemed dangerous could lose his pay, his promotions, and his rewards. No-one could build up a resource base large enough to challenge the whole system, because of the balance of weakness.

But more importantly, the senior commanders of these soldiers identified with the royal house and the aristocracy. They accepted the values of the court aristocracy, because many of them were related to it: they were junior branches of the royal household. When a line was six generations removed from the imperial main line, its members were re-classified as autonomous families of modest court rank. They took the surnames Minamoto and Taira, and were given posts both at court and away in the provinces. They still thought of themselves as aristocrats, their identity relied on the system continuing as it did. They did not make trouble for the senior branches of their families, still less for the emperor. They accepted the court nobility’s claims of superiority, and thought of themselves as inferior because they were fighting men. They worked for the imperial bureaucratic order, not against it, even as their actual power within the system grew and grew.

Warriors emerge clearly into the historical record when for the first time, in the early twelfth century, the retired monarch hired Minamoto men as a personal bodyguard. As with all Hei’an honors, this one became a target of struggle – everyone wanted it – and when tired of the Minamoto quarrelling, the retired emperor selected Taira no Kiyomori instead, a man who had proven his valor in fighting pirates. Now armed men were in the capital, and by 1156, they were drawn into factional struggles over the throne.

From 1180-1185, Taira and Minamoto fought one another (not necessarily along family lines) in the Genpei War, until Minamoto no Yoshitsune defeated – and wiped out -- the Taira. Minamoto no Yoritomo, meanwhile, had built up a base at Kamakura, east of Kyoto. In return for his competent service and a guarantee of income, the emperor recognized his right to govern all military personnel on his behalf – a kind of regency and division of power that was new, but not really strange since Hei’an authority had been divided in so many ways for so long. The Kamakura “tent office” (bakufu) continued the Hei’an warrior mission of protecting the emperor and the aristocracy. They did not do much fighting at all.