2.8: Confucius

- Page ID

- 135206

Into this world was born the first of the philosophers. Confucius or Kong Qiu (551-479 BC) was born in tiny Zhulou, a few miles south of Qufu, the capital of the domain of Lu. Lu already controlled Zhulou by that time, but for another thousand years, until the sixth century AD, sources call it a non-Zhou, “barbarian” (Yi 夷) culture.14 Confucius had to learn Zhou ritual as an outsider, but when he did, he loved it, and lamented its decay. He thought that elite families should follow the old rules about who could properly make offerings to which spirits and how, as well as the old aristocratic etiquette of daily interactions. After all, ritual expressed the divinely-appointed human hierarchy of the Zhou system! (We have seen already that ritual changed over time.) But as Confucius aged, he made a different argument: that rituals had to be based in sincere human emotion. This focus on sincerity meant both that some change in ritual was acceptable, and that rituals expressed and shaped human emotion, rather than being primarily ways to manipulate the spirit world. A man who strove for both sincerity and correctness in ritual would cultivate his own moral nature and thus his spiritual power. (Confucius says very little about women and had no female students.)

The life of Confucius has been imagined in many ways. Sima Qian’s Shiji has the first biography, presenting a man who made his difficult life harder by being a know-it-all who fairly consistently alienated people in power. According to Sima, Confucius was the illegitimate child of an elderly lower-level official in Lu, who learned who his father was only when his mother died. He spared no expense to bury his mother with his father, asserting his claim to be a low ranking aristocrat – a shi 士 – as his father had been. He managed to learn a lot about ritual, gathered some students, and got hired by one of the so-called “Three Families,” ministerial families just about to usurp the power of the Duke of Lu, inventorying grain in the granary of the Ji clan and then managing their sheep and cows. For long years he travelled around to the neighboring states, seeking influence with both legitimate and illegitimate rulers –over the objections of his disciples to the latter. He was fired as often as he was hired.

Confucius’s success in office came sometimes came from knowing all kinds of odd facts about the past; sometimes from his knowledge of ritual, still important to Zhou aristocrats (or they would not have bothered to abuse it); sometimes from hard-headed diplomacy; and sometimes from policies that benefitted the economy and brought order. At the age of 56, he became a local ‘justice of the peace’ in his home state, executed one of the usurpers, and began to turn Lu into an honest and thriving community. He was foiled on the brink of success by the rich and powerful neighboring state of Qi, which sent gifts of eighty beautiful girls and one hundred beautiful horses to the Duke of Lu. The gifts successfully distracted the entire court with sex and hunting, and Confucius quit in disgust. He retired for eight years to edit the Five Classics – says Sima Qian. In old age, Confucius acquired a little humility, learning to consult with his disciples and listen to others. He learned to care less about what others thought of him and to be at ease in just doing and teaching what he thought was right.15

Sima’s Confucius was not an extraordinary person who perfectly embodied learning and morality from day one. He was a flawed mortal of relatively lowly status (like Sima Qian himself) who made plenty of mistakes of judgment and even of ethics, but who learned from his mistakes and from other people. He slowly cut and polished his own character, and taught others.

The Hundred Schools

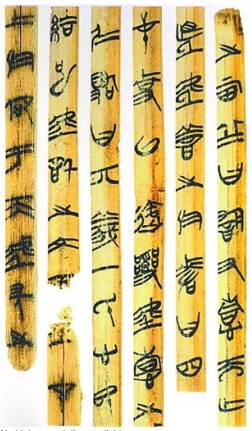

Confucius and his disciples opened the door to theorizing in rational and ethical terms about governing and individual roles. Until about the time of Confucius, very few people even among aristocrats – mainly the scribal clans – were literate, and “texts” were transmitted orally. That is why the Analects record pieces of conversations, not extended considerations of complex philosophical questions. After the Analects, some schools produced longer essays. As they parlayed the new ease of writing into longer and more complex arguments, all later thinkers had to agree or disagree with Confucius (or both); they could not just ignore Confucian thought.

The “Hundred Schools” – meaning “schools of thought” or communities of like-minded thinkers – center on various “masters.” Conventionally, we talk as if the different schools of thought were born dogmatically divided. But in the ancient intellectual world, as people freely debated a wide variety of questions, all schools drew on old texts, like the speeches of the early Zhou rulers and other texts that were being (at the same time) gathered into the Classics, and on stories of sage-kings and other mythical and historical figures. If one debater came up with a pithy anecdote, someone else would borrow it, perhaps to make a different point. The thinkers also shared knowledge of ritual and present-day politics, and their debates both drew on the distant past (real, imagined, or falsified) and were directed at current power struggles and conditions. We have only a fraction of what they wrote down, although new texts are being excavated, and still less of what they said.

We conventionally attribute the writings of the Hundred Schools to single teachers or authors, like Confucius, Mencius, and Laozi. But like the Classics, they were composed or compiled by numerous people. As one historian explains, “It has long been recognized the most of the received classical texts from ancient China are composite texts that were built up in layers over decades or centuries, passing through the hands of numerous copyists, compilers, and editors, some of whom also fulfilled the role of pseudo-authors.”16 Each began as a collection of sayings or conversations or thoughts, put together by a group of people discussing and debating. Then someone who wanted to finalize the text and close the conversation, would invent an author (perhaps using the real name of a teacher), and tell of his death or departure. But often that did not succeed in finalizing the text, because the community was still thinking and talking. More stories would arise about the author, and they, along with more sayings and thoughts, might be incorporated into later versions of the text. This means that the author and the text were co-created by a community of thinkers, even if there was an actual teacher or author who started things off. Rather than the intentions of one person, the text reflects the shared understanding (including disagreements) of the group of like-minded people talking to (and about) each other, over time.17 It is conventional to treat each text as written by or about one central figure.

The various schools of thought share the idea that a loyal minister is one who keeps reminding his lord of his flaws, preferring honesty that supports the long-term well-being of the state to flattery that supports the current lord’s ego.18 Confucius’s disciple Mencius, in particular, comes across as unafraid to speak truth to power. Mencius also argued against another thinker, Mozi (c. 480-390), who explicitly opposed Confucians in several ways. First, Confucius had urged the nobles not to skimp on the rituals appropriate to their station, to carry them out fully; but he also criticized those who demanded too much grain from their subjects. Mozi pointed out that all the money spent on ritual came from the working people, so that these two aims were contrary. Funeral rituals and other kinds of ceremonies were just a waste, he thought; they should be cut back or ended. Second, the Confucians saw familial love as the foundation of morality. It was natural and right that a son should love his parents more than someone else’s parents, and by nourishing that feeling through ritual he could extend his concern to other people’s parents. Mozi saw family love as selfish: we should love everyone alike, not favoring our own children or parents. Finally, Confucius focused on the ethical development of the individual, and so each of his 70 or so disciples carried on his teachings in different veins, thinking for themselves. Mozi, on the other hand, did not value individuals. What mattered was the material good of society: peace, high population, plenty to eat.

Mozi was so committed to his message that he once walked for ten days and nights to stop a war, binding up his sore feet with strips torn from his robe as he walked. He demanded the same level of commitment from his followers. They all had to subscribe to the exact same doctrine, and follow the orders of a leader who assigned them to work for certain lords when the opportunity arose (often they specialized in defensive warfare). The leader taxed their official salaries and disciplined them to stick to the party line, even by death. Perhaps this is why Mozi’s movement ultimately failed: smart people rarely like being bossed around. But Mozi’s ideas were influential: for instance, it was he who made the strongest argument for meritocracy: that that the most qualified man should be put in office.

Daoists opposed ritual on other grounds, but also opposed elevating worthy men to office. At least, those are the surface messages of the texts Dao De Jing, and Zhuangzi. The Dao De Jing (Classic of the Way and Power) is associated with a possibly mythical figure named Lao Dao and called Laozi, “Master Lao,” or “Old Master.” It contains many layers of material: poetry and prose, proverbs and rhymes. On the surface, its message seems political, or perhaps anti-political and pro-nature, but it is also an esoteric spiritual teaching about meditation and other practices. In the Warring States period, Daoist adepts pursued longevity and special powers like flight, whether into realms of alternative consciousness or real realms beyond the human. The Zhuangzi is more discursive, telling stories and making arguments.

Confucians, Daoists, and Mohists all opposed offensive war, the basic condition of their time. Even a thinker/school closely associated with war, Sunzi, argued that warfare was so destructive that it was best to gain one’s end more cheaply if possible. But victory required knowing everything about a situation: the terrain, logistics, the weather, the capacities of troops and spies, but also how to manage psychological things like fear, punishment, and morale. The Sunzi makes great reading (find it on ctext.org) and was appreciated by military commanders at least since Cao Cao, who wrote its first surviving commentary as he gathered together the threads of leadership after the fall of Han in AD 202. Many of the Legalists, on the other hand, promoted warfare, but they enthusiastically echoed Sunzi’s drive for information.

Legalism arose as a practical result of interstate competition. Guanzi, for instance, wrote about what kinds of information should be collected on working households to make the most of their labor. He included the directive to “Inquire about the men and women who possess skills: how many can be usefully employed to make sturdy equipment? How many unmarried women remain at home engaged in domestic labor?”19 A book attributed to Qin advisor Lü Buwei recommended that state track “slaves, clothing, maps, bows, chariots, carts, boats, oxen, palaces, wine, wells, mortars (for grinding), physicians, and shamans,” as well as omens.20

Legalism gathered theoretical strength in essays written by Xunzi (3rd century BC). A disciple of Confucius, Xunzi was criticized or neglected by later Confucians. He argued that rituals were not timeless expressions of the ways of heaven and earth; rather, they were manmade and purposely deployed by rulers. If rituals could be deployed for government, rather than valued for themselves, then other means of managing people could also be justified: laws and punishments. Laws and punishments were not new; what was new was the idea that they were the best, or only, way to create social order. Xunzi’s student Han Feizi (d. 233 BC), who worked for Qin, wrote that the idea of governing by virtue and ritual was nonsense as the chaos of the times showed. The only way to keeps people in line is firm, unavoidable punishment for breaking the law. And the law is established not by precedent, like ritual; nor by agreement among high-ranking men; but only by a supreme ruler, set above all others. Punishment for breaking the law should be as certain as it is that molten gold will burn your hand.

The next chapter will show how Legalism contributed to bringing down the system that Confucius cherished, and recombining all the feudal domains into a new mode: the empire.