11.6: South America c. 1500 - 1900

- Page ID

- 78210

South America c. 1500 – 1900

Spain and Portugal divided South America to exploit resources and convert souls.

Viceroyalty of Peru

The viceroyalty encompassed modern-day Peru as well as much of the rest of South America, the Portuguese controlled what is today Brazil.

1534–1820 C.E.

A beginner's guide

Introduction to the Viceroyalty of Peru

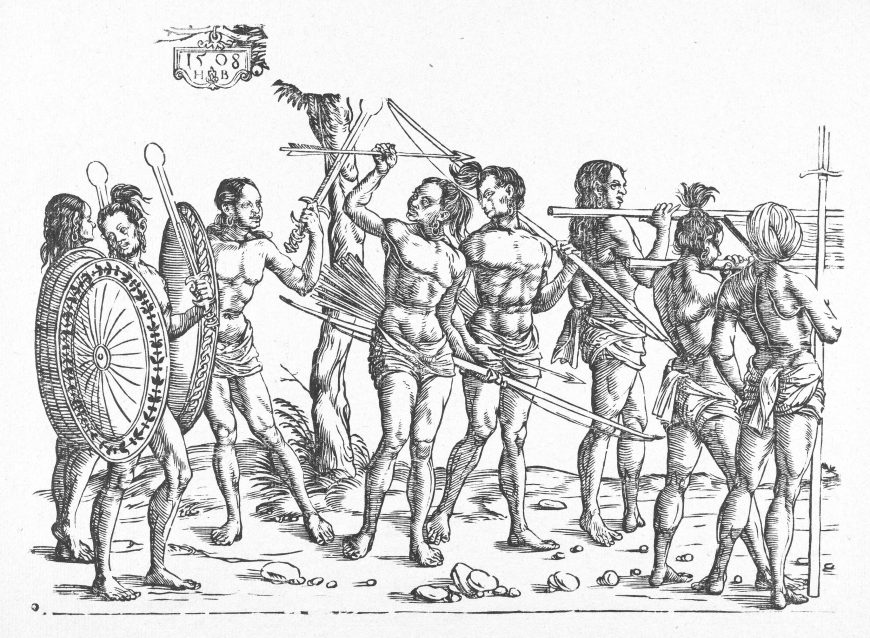

Francisco Pizarro and the conquest of Peru

In the early sixteenth century, the Inka Empire was in a state of turmoil due to a succession dispute between half-brothers Atahualpa and Huascar. They shared the same father, the penultimate Inka ruler Huayna Capac, who had died suddenly in 1527 without choosing an heir to the throne. Atahualpa, based in the northern Inka city of Quito, was in the process of consolidating the northern reaches of the empire in modern-day Ecuador and Colombia while Huascar commandeered Cuzco in the south. The half-brothers instigated a civil war that rocked the empire’s foundations to its core. Atahualpa and his powerful army ultimately managed to defeat Huascar and ascend to the throne.

It was at this very same time, however, that Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro arrived on South American soil. With news of white-skinned strangers arriving in the northern highland city of Cajamarca, Atahualpa traveled northward to greet the new arrivals in November of 1532. Atahualpa arrived in Cajamarca with a large retinue of attendants and soldiers. While the initial encounter between the Inka and the conquistador was an amicable one, tensions flared after the Spanish friar and translator Vicente de Valverde handed Atahualpa a breviary (liturgical book) to ascertain his receptiveness to Christianity, a religion about which the Inkas, of course, had no knowledge whatsoever.

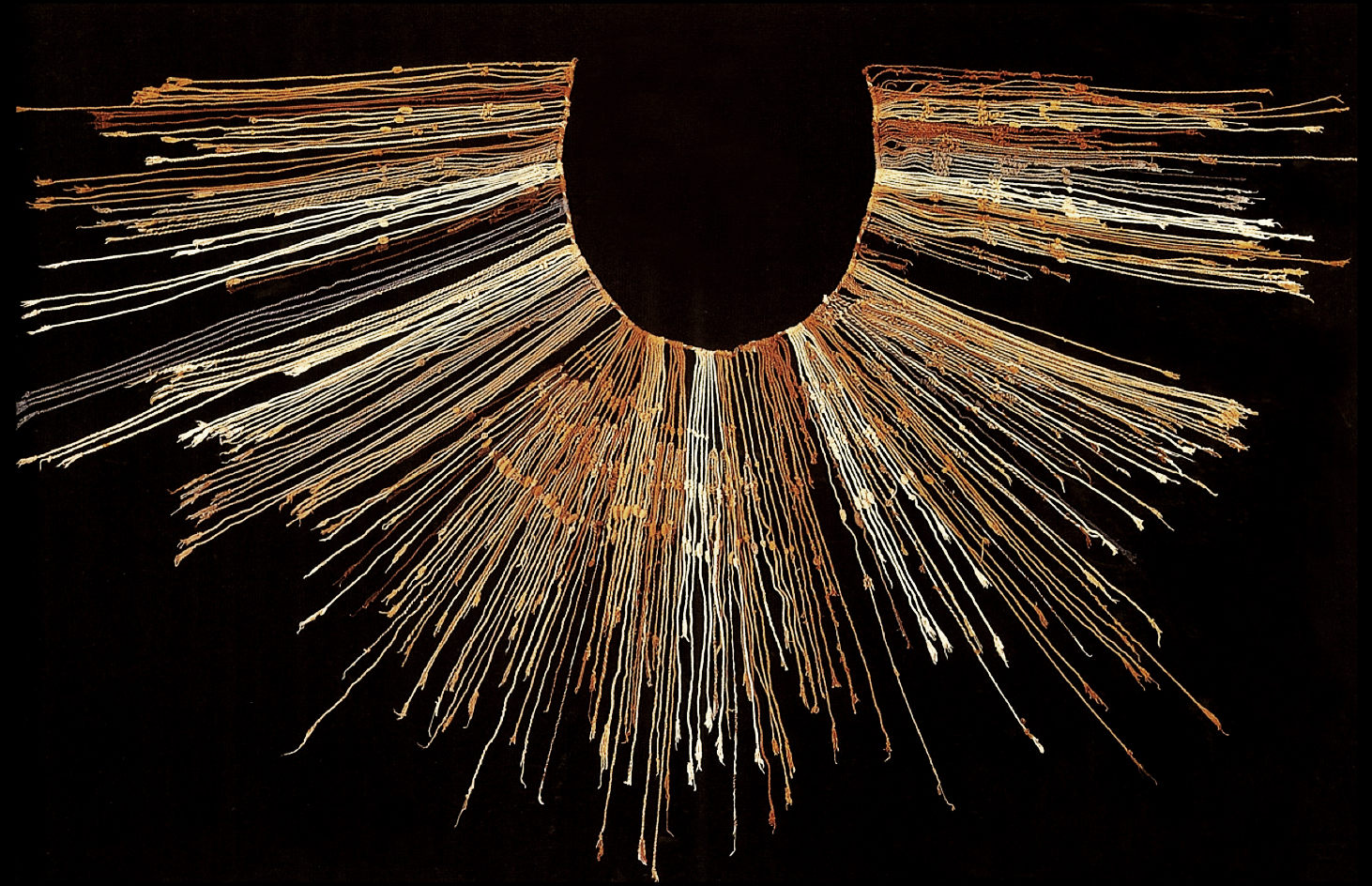

Since the quipu served as the primary system of communication in the Inka empire, Atahualpa had no concept of a “book” in the European sense of the term. According to the chroniclers of the Spanish conquest, Atahualpa threw the book to the ground. This perceived act of disrespect—of throwing the sacred book, and by extension, the word of God—to the ground provided the conquistadors with justification for ambushing the city and taking Atahualpa as their captive.

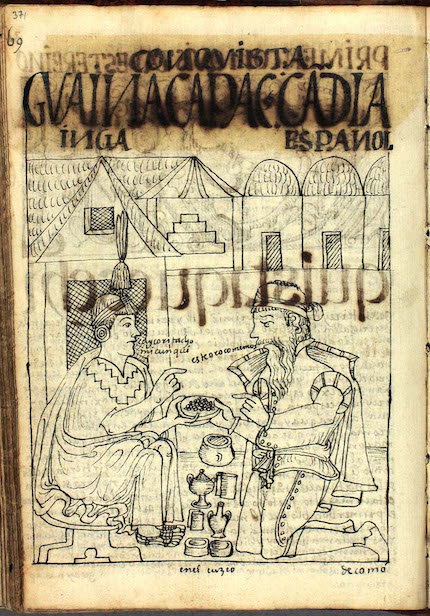

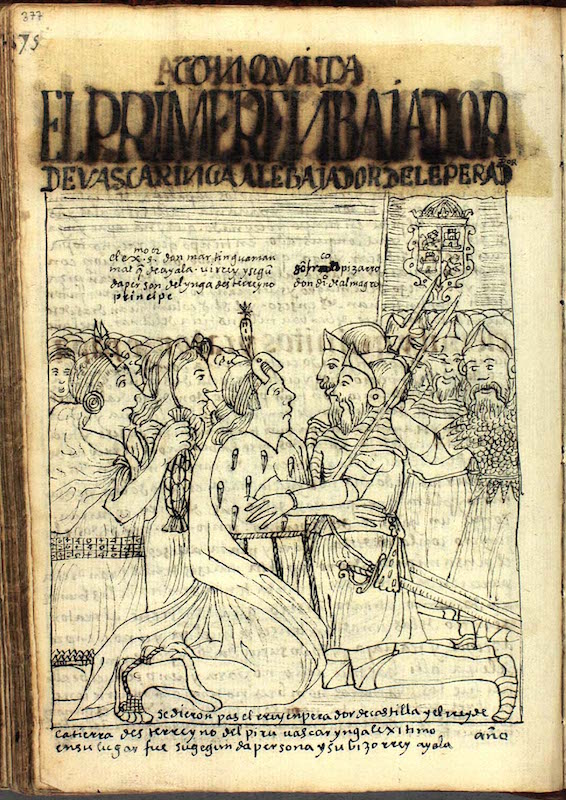

This pivotal moment in the Spanish conquest reveals the fundamental cross-cultural misunderstandings that took place during the early years of the Spanish invasion. While a number of translators facilitated dialogues between Spanish conquistadors and Quechua-speaking Inkas, their radically different world views and ways of life often defied simple linguistic translation. In his attempt to negotiate with Pizarro, Atahualpa promised to fill up a room measuring twenty-two feet long, seventeen feet wide, and eight feet high with gold and silver as ransom in exchange for his freedom. He agreed that the room would be filled entirely with gold, and then with silver twice over, all within the span of two months. The indigenous chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala (ca. 1535–after 1616) illustrated this scene in his El primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government), a 1,189-page manuscript written to King Philip III (1578–1621) in protest of Spanish colonial rule.

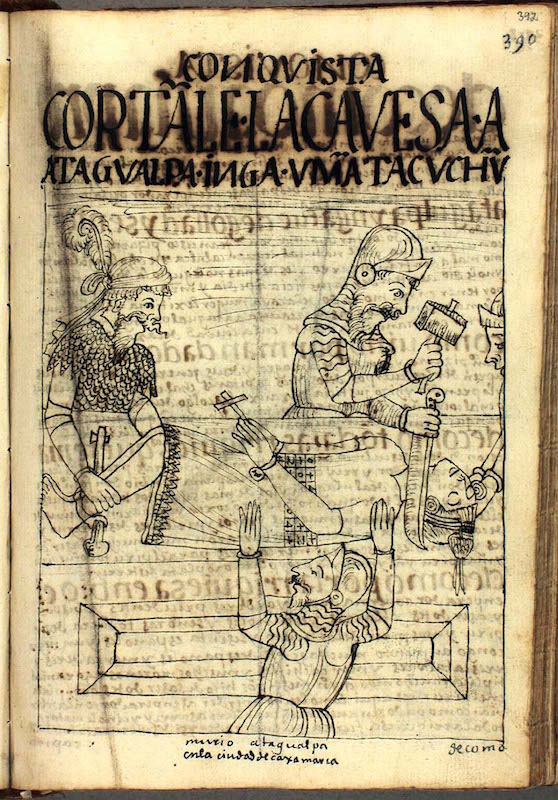

Despite Atahualpa’s miraculous success in coordinating donations of precious metals, he was publicly garroted (strangled) in 1533 on trumped up charges of idolatry and for the murder of Huascar. Pizarro’s army invaded the Inka capital of Cuzco on November 15, 1533, thus solidifying the Spanish triumph over the Inka empire. In some ways, the Spanish victory was inevitable. Inka stone and wooden weaponry were no match for Spanish metal armor, swords, and harquebuses (a type of proto-musket).

Pizarro and his army also capitalized on the deep political fractures within the Inka empire caused by the succession battle and received ample support from Atahualpa’s detractors. Nevertheless, Inka resistance delayed the full consolidation of Spanish colonial rule in the Andes until the execution of Tupac Amaru, the last ruler of the Neo-Inka state, a semi-autonomous faction that ruled from 1535 until 1572 in the secluded tropical outpost of Vilcabamba.

The effects of the Spanish conquest

The Spanish conquest of the Inka Empire brought about fundamental changes to the Andean social, political, and cultural landscape. The dismantling of Tawantinsuyu (the Quechua term for the Inka Empire) resulted in the irrevocable loss of Inka self-governance and the implantation of Spanish colonial rule. Spaniards quickly established themselves throughout the newly conquered region, often in pre-Hispanic urban centers. The former subjects of the Inka empire were forcibly resettled into indigenous settlements known as reducciones, while Spaniards settled in cities throughout Andean South America inhabited primarily by Spanish and criollo (Latin American-born Spaniards) residents. High tribute quotas were imposed on indigenous peoples that required participation in laborious public works projects and the mining of precious metals on a rotational basis. Inka religion became the target of Spanish missionaries, who associated it with idolatry and devil-worship based on a profound misunderstanding of Inka religious practice.

Spanish colonial rule, which lasted from 1534 into the 1820s exerted a profound and destructive impact on the lives of Peru’s indigenous inhabitants. However, the conquest and colonization of the Andes did not result in the complete eradication of indigenous peoples or indigenous practices. The visual arts of the colonial Andes stand as a testament to the resilience of native peoples in the post-conquest world. Native Andeans continued to express themselves artistically alongside and in collaboration with Spanish, mestizo, criollo, Asian, and African-descended peoples. Pre-Columbian artistic traditions cultivated over the course of several millennia entered into dynamic contact with imported European models to produce stunning and culturally complex works of art.

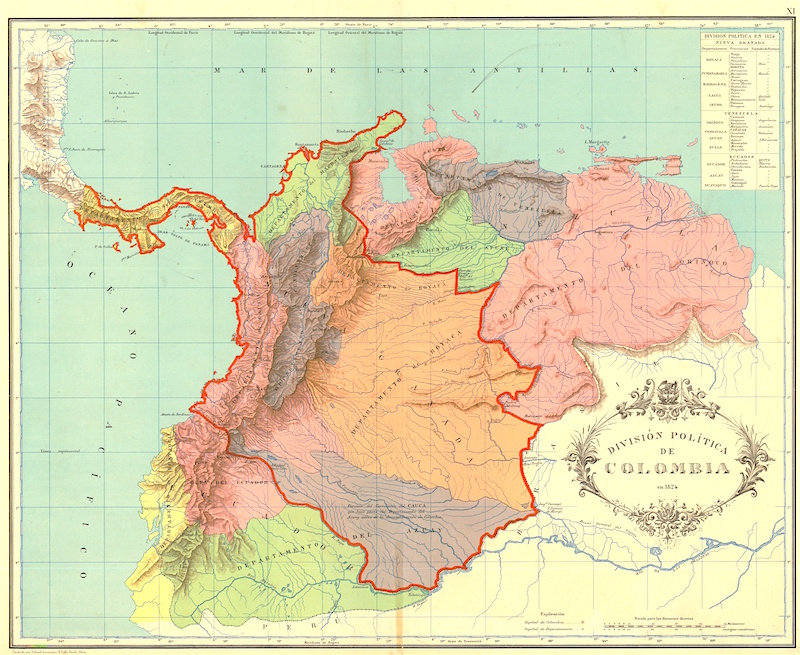

Establishment of the Viceroyalty of Peru and its artistic centers

The Viceroyalty of Peru was established in 1542 and encompassed part or all of modern-day Venezuela, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina, and even some of Brazil, making it the largest viceroyalty in the Spanish Americas. By the eighteenth century, however, the Peruvian viceroyalty dramatically reduced in size with the establishment of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717 and the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata in 1776.

At its height, the Viceroyalty of Peru was a burgeoning administrative district and hotbed of artistic activity. The coastal city of Lima, founded in 1535 by Pizarro, was assigned the capital of the viceroyalty for its accessibility and proximity to crucial trade routes—Cuzco’s high altitude and relative isolation was deemed an obstacle to Spanish political and economic interests. Artistic centers emerged throughout the viceroyalty’s major cities, including Lima, Cuzco, and Arequipa in present-day Peru, Quito in present-day Ecuador, and La Paz and Potosí in present-day Bolivia. The new artistic and architectural traditions that emerged under Spanish rule played a critical role in ensuring that the viceroyalty’s inhabitants were devout Catholics and loyal subjects of the Spanish crown.

At the same time that the visual arts reflected Spanish colonial interests, however, they also held the power to challenge and subvert them. The visual traditions borne out of colonialism are often layered with multiple registers of meaning that transmitted different messages depending on the cultural identity of the viewer. The arts of colonial Peru are neither fully pre-Columbian nor fully European, but a dynamic combination of both.

Additional resources

Kenneth Andrien, Andean Worlds: Indigenous History, Culture, and Consciousness under Spanish Rule, 1532–1825 (Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 2001).

“South America, 1600–1800 A.D.” on the Met Museum Timeline

María Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, History of the Inca Realm (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and the Moon (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2012)

Kris Lane, “Conquest of Peru” (Oxford Bibliographies, 2011)

Portrait Painting in the Viceroyalty of Peru

Portraiture functioned as an important artistic genre for wealthy elites to assert power and legitimacy in the Viceroyalty of Peru. From an art historical perspective, portraits also transmit a wealth of information about prevailing trends in clothing, jewelry, and other accessories with which the sitters are represented.

Portraits as visual documents

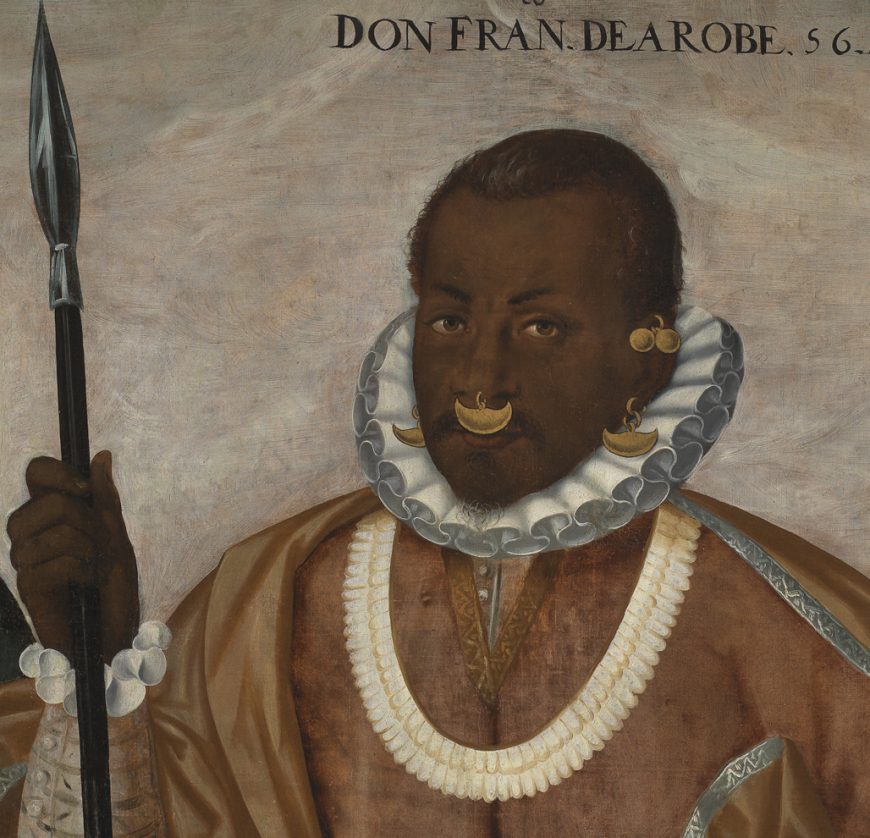

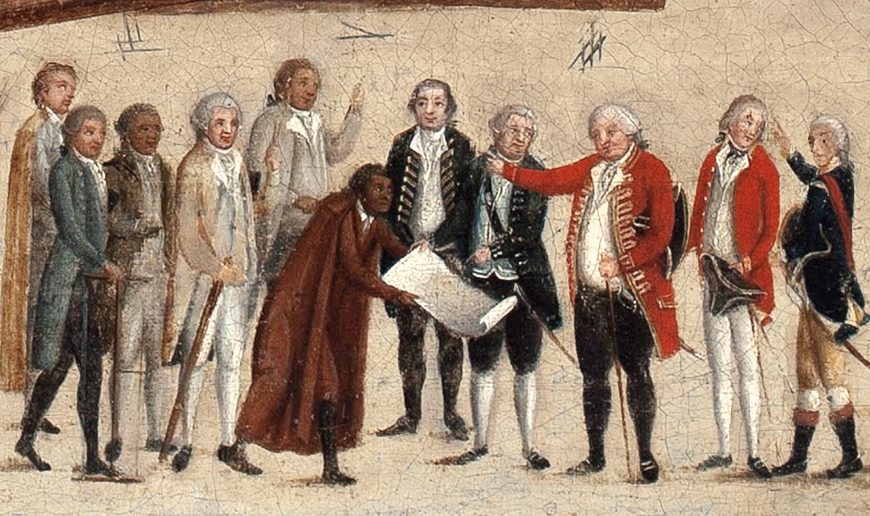

Any discussion of colonial Andean portraiture must begin with Andrés Sanchez Gallque’s Three Mulatto Gentlemen of Esmeraldas from 1599, as it is the first signed and dated canvas in South America. The indigenous Quito artist depicts three men of indigenous and African descent. Don Francisco, at center, is flanked by his sons Don Pedro on his left and Don Domingo on his right.

All three of the men wear clothing associated with varying cultural affiliations. The stiff ruff collars and sleeves (called lechuguillos, or “little lettuces”) pay homage to Spanish and Flemish styles.

All three wear Andean uncus, or tunics, but the lustrous sheen of the fabrics suggests that they were fashioned from imported silk. Their necklaces derive from shells found along the coast of Ecuador, while the elaborate gold earrings and nose rings were likely fashioned out of gold extracted from mines in Colombia.

These men, in effect, embody a global material aesthetic made possible by the Spanish colonial enterprise. Taking up nearly the entirety of the picture plane, these men appear almost larger than life. Their open stance and steel-tipped spears further communicate a sense of power and authority.

A consideration of the historical context under which this portrait was produced, however, tells a different story. Don Francisco was the cacique (local indigenous ruler) of Esmeraldas, which had previously been an independent Afro-indigenous community on the north coast of Ecuador. In 1597, he submitted to Spanish authorities and the area became incorporated into the colonial bureaucracy. The judge responsible for this transfer of power, Juan de Berrio, commissioned this portrait as a gift to the Spanish King Philip III to commemorate his subjugation of the region. The portrait reveals the tensions of power at play in the realm of visual representation; Don Francisco and his sons assert the same kind of colonial authority to which they are also subjected. This image also demonstrates the power of portraits to act not only as depictions of an individual’s likeness, but as a visual “document” employed to commemorate political deeds.

Commemorative Portraits

Portraiture also became a tool for promoting alliances between members of the Spanish and indigenous elite. Marriage of Martín de Loyola with the Ñusta Beatriz and of Don Juan de Borja with Doña Lorenza Ñusta de Loyola, an anonymous canvas dating to c. 1680 that hangs in La Compañía Jesuit church in Cuzco, commemorates two marriages between Inka-descended women and prominent members of the Jesuit order.

The cartouche at the lower left, a common feature in colonial paintings, provides a biographical sketch of the figures depicted in the scene. The two central figures wearing black cloaks are St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, and St. Francis Borgia, who holds a human skull. On the left, Martín de Loyola, nephew of St. Ignatius, is shown marrying Beatriz Coya, a direct descendant of the Inka ruler Huayna Capac. To the right, Count Juan Enríquez de Borja y Almanza, grandson of St. Francis Borgia, marries the daughter of Martín de Loyola and Ñusta Beatriz.

The painting is not a realistic portrayal of reality, given the nearly forty-year gulf that separates the two marriages. Moreover, the former marriage occurred in Cuzco’s central plaza while the latter was performed in Madrid. Both locales are depicted in the respective backgrounds of the wedded couples. Instead, it is a commemorative portrait intended to demonstrate the seamless mixture of Spanish and Inka elite blood into perpetuity.

The power of history in the eighteenth century: Inka portraits

Portraits depicting the lineage of Inka and Spanish kings served as another means for solidifying links between the Inka and Spanish aristocracy. Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru (c. 1725) depicts portraits of Inka kings from Sinchi Roca to Atahualpa, followed by portraits of Spanish monarchs from King Charles V to Ferdinand VI. At the top left and right are portraits of Manco Capac and Mama Huaco, the mythical founders of the Inka empire. Textual glosses identify and describe the deeds of each king. A portrait of Christ at the top center holding an olive branch, sword, and cross creates a compositional triangulation that places him at the apex of a hierarchy of rulership. Paradoxically, the Inka kings are positioned closest to Jesus rather than their Spanish successors.

The organization of the image creates a productive tension between two types of visual readings: viewing the image as composed of a tripartite spatial scheme with Christ and the Inkas occupying the “celestial” plane; or viewing it in conjunction with linear time, from left to right and top to bottom, implying a narrative of progress culminating in Spanish power.

Other aspects of the image show more definitive assertions of colonial power. The figure of the Inka king Atahualpa, located in the second-to-last cell in the middle row, looks directly at the Spanish King Charles V, pointing his lowered staff toward the Spanish king as a gesture of submission. Charles V points his finger to an illuminated cross, suspended in air to symbolize the entry of Catholicism to Peruvian lands. Atahualpa’s offering gesture served to normalize the conquest as a natural transfer of power.

These eighteenth-century lineage portraits attest to a renewed interest in the Inka past at a time when privileges granted to indigenous elites began to be curtailed under the Spanish Bourbon monarchy (1700–1808). Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru asserts the primacy of the Spanish monarchy while also attesting to Inka cooperation in the creation of a Christian colony. Loyalty served as a crucial tool of political diplomacy in Spanish-Inka negotiations.

Elite criollo portraits

Elite criollos (people born in the Americas, but of Spanish lineage) also commissioned large-scale portraits for display within private residences. Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar (c. 1780), attributed to the artist Pedro José Diaz, depicts a wealthy member of Lima society who rose to local fame due to her involvement in a marital scandal. Belsunse y Salasar was unhappily married to an older man and decided to request a one-year grace period before consummating the marriage. She spent the subsequent year as a nun in a local convent where she stayed until he died. Upon his death, she resumed her life in Lima society and married one of his younger relatives, Agustín de Landaburru y Rivera.

This portrait was painted after her return from the convent and displays a confident woman expressed through her three-quarter pose and direct eye contact with the viewer. Her finely detailed blue silk dress with lace sleeves reflects popular European fashions of the eighteenth century. The arched doorway looks out onto a tree-lined walkway with a fountain at the center, representing a park that she and her second husband donated to the city of Lima around 1755. This strategic inclusion in the portrait served as a means to highlight her social largesse and civic engagement. She delicately holds a fan in the right hand to connote modesty. The array of silver objects and jewelry in the portrait emphasize Belsunse y Salasar’s access to luxury goods, which she touches or wears as a means of embodying and even “performing” wealth. Unlike Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru, which communicated power through recourse to history, Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar remains firmly rooted in the present.

Identity and rebellion

Indeed, it was members of the criollo elite like Doña Mariana whose sights were fixed on the prospect of a future sovereign nation state — independent of Spain. At precisely the same moment when her portrait was painted in Lima, the southern Andean regions of Cuzco and La Paz were embroiled in bitter political conflict. The indigenous-led Tupac Katari Rebellion (1777–1780) in Alto Peru (present-day Bolivia) and Tupac Amaru Rebellion (1780–1783) sought to overthrow Spanish colonial rule and institute an indigenous power structure that drew inspiration from the Inka empire. The political conflict emerged largely as the result of increased economic burdens on indigenous peasant communities in the eighteenth century. These violent insurrections pitted natives against Spaniards, mestizos against criollos, and even native Andeans against each other, who were divided between Loyalist and Rebel factions.

The aftermath of the Tupac Amaru rebellion incurred around 100,000 deaths, the vast majority of whom were indigenous. These anticolonial rebellions exerted a cataclysmic impact on the colonial power structure, but they did not directly lead to independence. The movements for South American independence in the 1820s were largely dominated by criollos who resented their secondary status to peninsulares (Spaniards born on the Spanish peninsula) under the new Bourbon dynasty. The establishment of Latin American nations in the nineteenth century led to the development of new artistic genres, art academies, and arenas for the display of artworks. Nevertheless, colonial art left a longstanding legacy on the modern and contemporary arts of the Andes. Many of the portraits of South America’s liberators, for example, retain the same preference for flatness and poses found in eighteenth-century colonial portraits.

Additional resources:

Susan Verdi Webster, Lettered Artists and the Languages of Empire: Painters and the Profession in Early Colonial Quito (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017)

Thomas Cummins, “Three Gentlemen from Esmeraldas: A Portrait Fit For a King,” in Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, ed. Agnes Lugo-Ortiz et al., 118-45. (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 126-38.

Learn more about the Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar

16th century

Introduction to religious art and architecture in early colonial Peru

Signaling Spanish dominance in Cuzco, Peru

The transmission of Christianity to the Andes was both an ideological and artistic endeavor. Early missionaries needed to construct new spaces of worship and create images illustrating the tenets of the faith to recent converts.

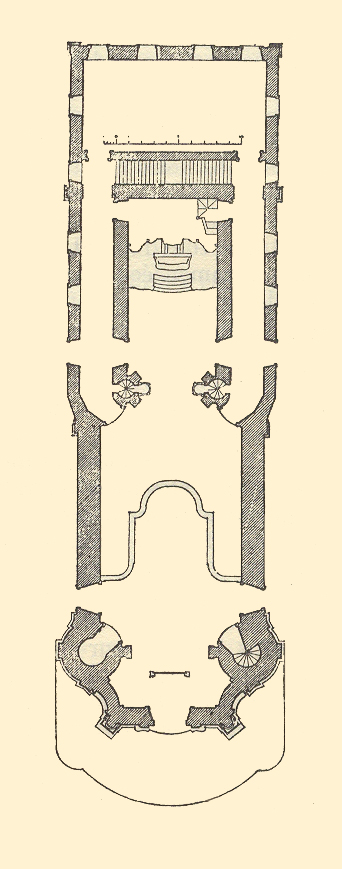

The Convent of Santo Domingo in Cuzco (also spelled Cusco) offers an early glimpse into the evangelizing zeal of Peru’s mendicant orders’ project to create Christian structures atop the ruins of this recently conquered pre-Columbian city.

The church was founded by the Dominican order in 1534 and built directly on the remains of the Coricancha (also spelled Qorikancha, meaning “golden enclosure”), Cuzco’s most important Inka (also spelled Inca) religious temple. The remains of the Inka temple form a curved foundation for the church. A small chapel rests on top of the curved wall at the back of the main church.

The placement of a Spanish Christian structure atop a decapitated Inka temple is a symbolic act of power and subjugation. The church serves as a material manifestation of the “triumph” of Christianity over paganism, hovering over the ruins of a conquered civilization. On the other hand, the Convent of Santo Domingo pays homage to both Spanish and Inka traditions. The church has an austere fortress-like façade with a three-arched entryway supported by Solomonic columns. Above that, the shuttered balcony is reminiscent of Hispano-Islamic (often termed mudéjar) architectural antecedents. Four of the original rooms of the Coricancha became incorporated into the cloister of the Church, giving both the exterior and interior a culturally mixed architectural signature. The finely cut masonry and trapezoidal windows of the original Inka structure became juxtaposed with the convent’s Baroque architectural flourishes modeled on European churches.

The Coricancha’s former function as an Inka religious temple dedicated to the sun does not necessarily disappear with the arrival of Christianity, but rather becomes intertwined with Christian notions of divinity. By choosing the most sacred site of the former empire as a site for conversion and worship, the Dominican missionaries recognized the transcendent power the Coricancha once held, and reoriented it toward a new dogmatic enterprise.

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century chronicles of the conquest of Peru are rife with references to the unparalleled quality of Inka stonework; the Spaniards marveled at the ability of Inka stonemasons to produce mortarless structures whose stones were so closely aligned that one could not even fit a knife through their seams.

What at first sight may seem like an architectural incongruity, the interplay of Inka and Spanish stonework demonstrates the continued importance of Inka art forms in the colonial period as well as the intercultural exchanges that occurred in the making of colonial Cuzco.

Missionary spaces in the Collao region

The missionary activities of the Dominican order extended far into southern Peru in the Lake Titicaca region. Clustered in this region of southern Peru, the missions of Juli, Pomata, and Chucuito share a number of similar features.

These mission churches formed a critical component of indigenous towns known as reducciones or pueblos de indios, which were instituted by the controversial Viceroy Francisco de Toledo during his appointment from 1569–1581. Reducciones were intended to isolate indigenous communities from their ancestral lands and shrines as a means of exerting political control and facilitating their conversion to Christianity.

The Church of La Asunción in the town of Chucuito, for example (in the Collao region of southern Peru) forms part of a large collection of Dominican mission complexes dedicated to the evangelization of native Andeans. The expansive adobe church emulates the large-scale mission churches of New Spain, also known as conventos. Like its colonial Mexican counterparts, the Church of La Asunción features a large atrium surrounded by a colonnade. The extensive outdoor space would have accommodated large congregations and also resonated with pre-Columbian Andean traditions of outdoor worship.

A restrained classicizing Renaissance-style carved stone façade frames the entry portal, flanked by pilasters and columns and topped with a pediment. Two carved niches on each side of the doorway may have originally contained sculptures of saints. The decorative relief carving along the arch and pediment provided an opportunity for Chucuito stonemasons to showcase their skills.

Early religious painting

Early painting of colonial Peru also served the didactic purpose of instructing indigenous people in the tenets of Catholicism through the language of images. European iconography traveled to the Andes through robust transatlantic trade networks that brought prints, pigments, paintings, brushes, and other art-related materials from Italy and Flanders by way of Seville, Spain.

European artists also traveled to South America to help meet the growing demand for religious images. One such artist was the Italian émigré Bernardo Bitti. Bitti, a member of the Jesuit order, trained in Rome, where he spent the early part of his artistic career. He subsequently spent time in Seville before arriving in Lima in 1575. He worked throughout the Viceroyalty of Peru, completing artistic commissions in Cuzco, Arequipa, La Paz, Potosí, and Chuquisaca.

One of his best-known paintings, entitled The Resurrection of Christ and dating to 1603, hangs in the Capilla San Ignacio in Arequipa’s La Compañía church. Christ’s serpentine, elongated figure pays homage to Italian Mannerist painters such as Jacopo Pontormo and Correggio.

A number of Bitti’s disciples emulated his characteristic muted color palette consisting of pastel pinks and blues and crisply folded drapery, extending Bitti’s artistic influence far into the seventeenth century. Bitti’s uncluttered compositions transmitted Biblical themes in a direct and engaging manner.

Additional resources

SAFE (Saving Antiquities for Everyone), Cultural heritage at risk: Peru

Introduction to Andean Cultures

The lofty ambitions of the Inca, National Geographic

The Inca road, Smithsonian Magazine

Early Viceregal Architecture and Art in Colombia

In 1499, Alonso de Ojeda became the first Spaniard to step on what is today Colombian (as well as Venezuelan) soil. Often credited with circulating the myth of El Dorado, Ojeda’s expedition prompted that of later conquistadors, among them Jiménez de Quesada and Sebastián de Benalcázar. In 1525, the Caribbean coastal city of Santa Marta was established as the first Spanish settlement in Colombia, however it was the cities of Bogotá, Cartagena de Indias (commonly known as Cartagena), Tunja, and Popayán that would eventually rise to prominence.

Popayán, for instance, was a highly profitable city as a result of its reliance on mining and slavery, which ensured substantial wealth for the city, and thus permitted the commissioning of impressive religious monuments. Before Bogotá was proclaimed the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Granada (the name given to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in northern South America) in 1717, the city was home to the President of the Audiencia of Santa Fé, whose job was to oversee the Colombian provinces and report to the Viceroy in Lima.

An early colonial church in Bogotá

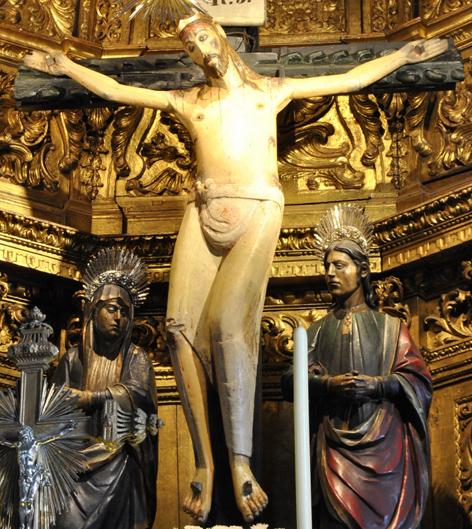

In Bogotá, the oldest surviving colonial church (1556) bears a modest façade in comparison to what is found inside. Featuring one bell tower and a single nave interior, the Church of San Francisco features an elaborate retablo (altarpiece) that invades the entire area of the apse (the semi-circular at one end of the church).

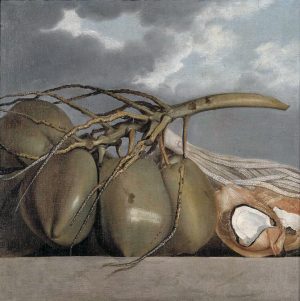

The retablo is gilded, and adorned with biblical sculptures (such as St. John writing the Apocalypse), spiral fluted columns, and indigenous plants like coconut and chontaduro palm trees (chontaduro is the fruit of a palm tree that is native to the Pacific rim of Colombia). Not only does this demonstrate that the convergence of local and foreign iconography (symbolism) was a widespread practice in the colonies, but also that it was a trademark of early colonial churches, when the process of evangelization was in its early stages.

The Fortified City of Cartagena

Cartagena, founded in 1533, is located on the Caribbean coastline of Colombia. The city played an influential role in the dissemination of enslaved Africans throughout the viceroyalty. Due to its strategic position, Cartagena was not only an important trading post, but also a prime target for invaders, explaining the overwhelming presence of fortresses throughout the city. Starting in 1610, it also served as the seat of the Spanish Inquisition (founded in 1478 by Ferdinand and Isabel — King and Queen of Spain — to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms), which established only three Holy Offices in Latin America, one of which was Cartagena.

The city of Cartagena served as an important entry point into the Viceroyalty. Much like Veracruz, Cartagena was — and still is — an active port city. Enslaved people, gold, and silver were stored, exchanged, and shipped from Cartagena, which became wealthy and powerful during the colonial era. As a result, Cartagena, like other port cities in the Caribbean, such as La Habana and San Juan, was surrounded by thick and crenellated walls, hence its Spanish name as “la ciudad amurallada” (“the walled city”). This colonial city, contained within more than six miles of fortified walls, is unique in Latin America.

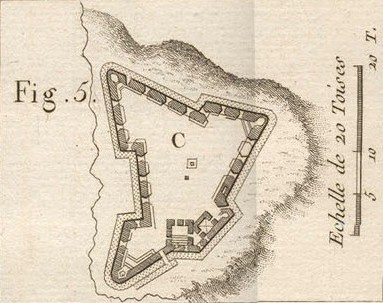

The Fortress of San Felipe, begun in 1630, was Cartagena’s main defense against French, Dutch, and English explorers, among them Sir Francis Drake, whose invasion of Cartagena in 1586 was known as the Caribbean Raid. These attacks continued into the eighteenth century, prompting various enlargements and renovations to the fortress. Located on a hilltop, the fortress provides a strategic view of both the city and port. Its thick walls (with foundations as thick as 65 feet), triangular design, and exterior ramp system make the fortress impenetrable, while a complex maze of underground tunnels connects this stronghold with the walled city.

Early religious architecture in Tunja

Tunja, founded by Jiménez de Quesada in 1539, and Popayán, founded by Benalcázar in 1537, are also located in vastly different regions of Colombia. Through the efforts of important art patrons (such as Juan de Vargas, Gonzalo Suárez Rendón, and Juan de Castellanos), Tunja emerged as an intellectual and humanist center.

In Tunja, the Church of Santa Clara was the first convent of colonial Colombia. Its interior features, like at the Church of San Francisco in Bogotá, includes indigenous iconography. The golden sun, located prominently above the apse, held special significance for the Chibcha, who considered it their principal god, as well as life giving force.

Surrounding the golden sun, and throughout the interior of the church, bodiless angels appear to float aimlessly. With their heads located at center and surrounded by six wings, these seraphim recall the golden sun.

The fact that these solar symbols were made explicit both on the walls of the church, as well as on liturgical pieces, demonstrates the importance of hybrid iconography in the evangelization process, while their repetition might suggest insistency and forcefulness.

The House of the Scribe in Tunja

Iconography also played an important role in domestic architecture, particularly that of the renowned scribe Juan de Vargas. Commonly known as the House of the Scribe, it served as the home of the Vargas family, who arrived to New Granada in 1564. Under the patronage of Vargas, as well as that of the Spanish priest Juan de Castellanos and the founder of Tunja, Gonzalo Suárez Rendón, a humanist tradition began to brew in Tunja.

Similar to what had occurred in Renaissance Europe, the teachings of the Church were combined with the ideas of classical philosophy, creating a culture that was as much intellectual as it was religious. This was reflected not only in the private libraries of Vargas and Castellanos, which contained books, prints, and manuals (many of them from Europe), but also in their art collection. At the home of Juan de Vargas for instance, an extensive mural program features a unique conflation of Roman mythology, Christian iconography, and European painting.

The mural features an iconography unlike any other in New Granada, and less common across the American continent at the time. It includes depictions of the Roman Goddess of Wisdom, Minerva, and the Goddess of Hunt, Diana, combined with religious symbols such as the Latin cross.

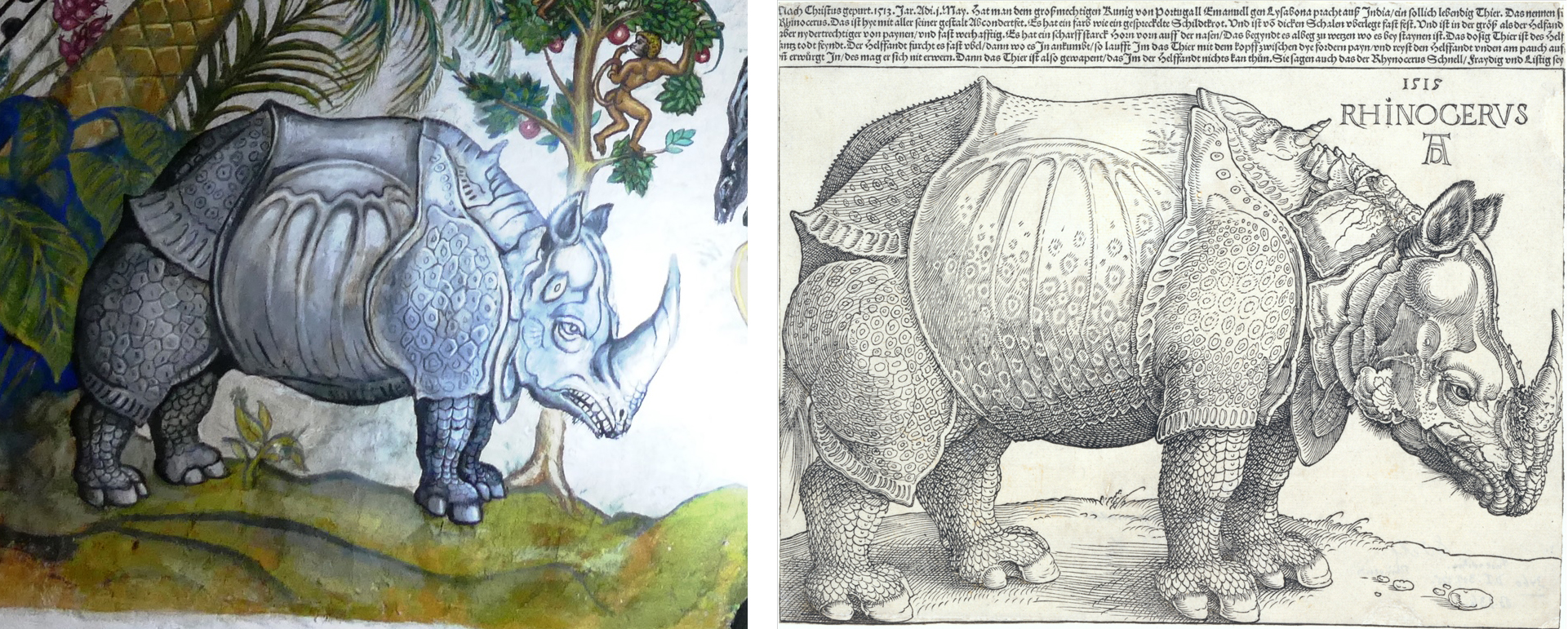

Even more interesting is the fact that these recognizable icons are set in a landscape of exotic flora and fauna, including a rhinoceros, which is not indigenous to Colombia. It is believed to have been copied from either an Albrecht Dürer print or from a copy of Dürer’s print by the Spanish engraver Juan de Arfe, published in De Varia Commensuración para la Escultura y Architectura (1587).

The end result is an eclectic combination of mythological and religious narratives set against a landscape of exotic figures, animals, and plants — revealing the cultural convergence that characterized the art of Spanish America.

Textiles in the Colonial Andes

As in the sacred temples of the Christians, and in the Apostolic Palace of the Pope of Rome, the royal or imperial palaces [of the Inkas] were commonly whitewashed with gesso or lime, and during solemn festivals they were accustomed to adorning them with beautiful and rich tapestries, and for those of the greatest solemnity they would add brocades and fabrics of gold.Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Historia general y natural de las Indias (General and Natural History of the Indies), 1492–1549

This statement, made by the Spanish naturalist and historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, describes the public use of textiles among the Inka in his Historia general y natural de las Indias (General and Natural History of the Indies), written between 1492–1549. Textiles were important in Inka culture, with the highest quality examples worth more than gold or any other luxury item.

Textiles remained important items after the Spanish conquest in the Viceroyalty of Peru. In general, non-religious art enjoyed widespread consumption among the Viceroyalty of Peru’s diverse populace. Clothing, tapestries, drinking cups, and portraits helped express social identities as well as the negotiation of cultural boundaries. Many pre-Columbian artistic traditions continued into the colonial period and became invigorated with new materials and systems of manufacture. This was certainly true of textiles.

Unkus

Although indigenous men were expected to adopt European-style dress, specialized weavers continued to produce uncus, or tunics, for special ceremonial occasions. A man’s tunic (above) dating to the seventeenth century features a colonial reinterpretation of a pre-Columbian weaving tradition. The tunic contains a band of tocapu along the bottom edge, which may symbolize the wearer’s geographical or ethnic affiliation.

Some of the colonial tocapu seem to lack any specific meanings and appear somewhat generic, leading some scholars to suggest that tocapu became associated with a generalized notion of “Inkaness” used as a way to assert elite indigenous status. A set of rampant lions with raised paws is embroidered along the bottom edge of the backside of the tunic, betraying its colonial manufacture. Lions are animals commonly used in European art whose iconography circulated throughout the Americas after the Spanish conquest.

This type of tunic would have been commissioned by members of the indigenous elite and worn during ceremonial occasions such as civic processions and religious festivals including the feast of Corpus Christi. We see individuals wearing specialized tunics in paintings showing the procession during this feast. Tunics woven in an Inka style allowed native Andean elites to reenact and reinvent Inka power within a new colonial context.

Tapestries

Tapestries also reveal a great deal about artistic cross-fertilization in the colonial Andes. Inka tunics belonged to a small segment of the population who claimed ties to the indigenous elite, while tapestries were enjoyed by a broader cross-section of the population (albeit the wealthy who could afford luxury goods). Textiles such as Tapestry with Pelican adorned the interiors of private residences as wall hangings or served as backdrops for religious and civic processions. The tapestry, which dates to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, attests to the robust trans-Pacific Manila galleon trade with which the Viceroyalty of Peru was engaged.

The iconography of the tapestry derives, in part, from embroidered Chinese silks that arrived in the Americas in large numbers after the fall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644. The pelican is depicted feeding her young with droplets of her own blood. As art historian Elena Phipps points out, this represents the Pelican in Her Piety, a common symbol employed by missionaries to represent Christ’s sacrifice. This serves as a reminder of the frequent presence of Christian themes even among artworks intended for private, non-religious consumption. The colorful tapestry also contains dogs, rabbits, parrots, horses, and Chinese mythological animals nestled among flowers and foliage giving it the appearance of a supernatural forest.

Textile murals

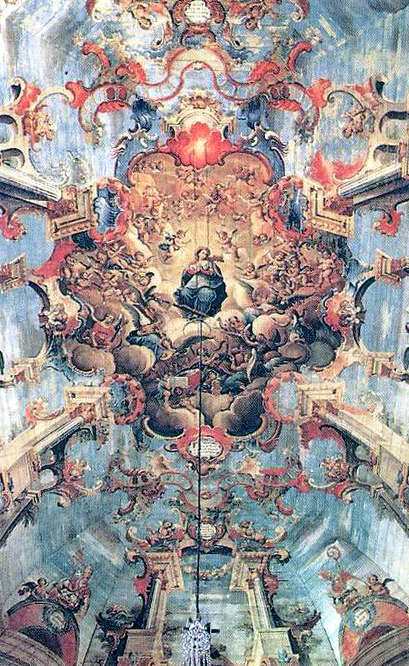

Tapestries figured so prominently in colonial Andean life that artists adapted their designs to a variety of artistic media. By the late seventeenth century, a number of rural churches throughout the Cuzco diocese featured “textile murals” that mimicked expensive brocades, laces, and tapestries but depicted with tempera paint applied to the walls in fresco secco (mural painting on dry plaster) technique.

One of the most impressive examples of a textile mural can be found at the chapel of Canincunca dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria in the Quispicanchi Province just twenty miles southeast of the city of Cuzco. The entire interior of the chapel appears to be “draped” with sumptuous wall hangings, which upon closer inspection are in fact trompe l’oeil paintings that imitate the design and texture of cloth. The textile patterns consist of urns with flowering bouquets and counterposed s-shaped curves with leafy appendages. The patterns and color scheme resemble surviving examples of colonial textiles with interlaced vegetal motifs and floral ornamentation.

Although the textile murals at Canincunca are in the religious context of a church setting, the designs themselves are abstract and contain no explicit references to Christianity. Textile murals hovered at the intersection of religious and secular art, endowed with sacredness by virtue of their location within religious spaces. The notion of “clothing” a church with painted simulations of cloth may have also participated in the personification of the church as a living, bodily entity, whose resonances with Andean beliefs around the animated quality of the natural world would have been especially palpable.

Additional Resources

Elena Phipps, Johanna Hecht, and Cristina Esteras Martín, eds., The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830 (New Haven: Yale University Press and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004)

Ananda Cohen Suarez, Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2016)

Ananda Cohen Suarez, Painting Beyond the Frame: Religious Murals of Colonial Peru, on MAVCOR

17th and 18th centuries

Guaman Poma and The First New Chronicle and Good Government

A very long letter

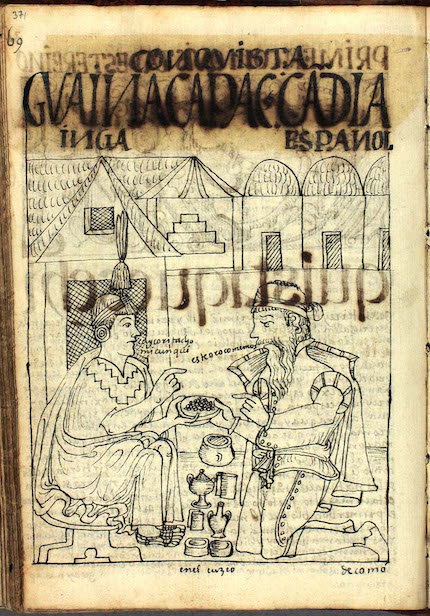

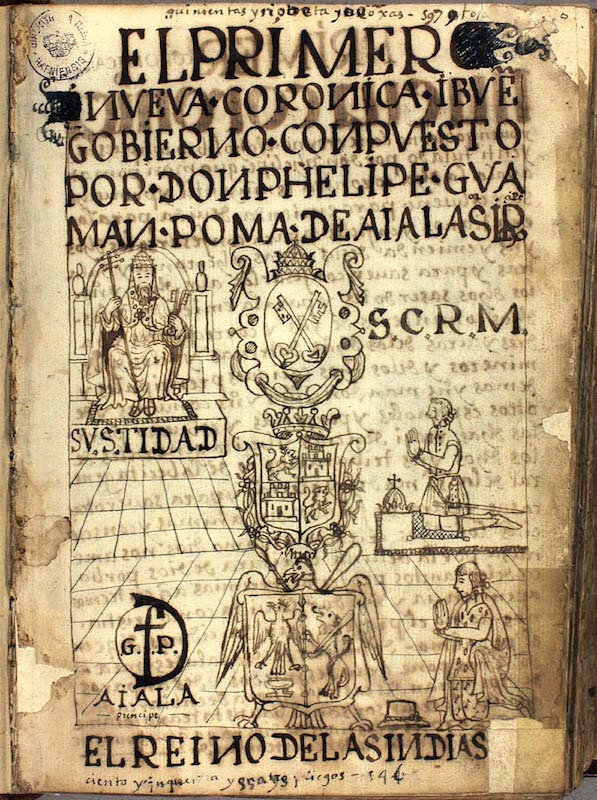

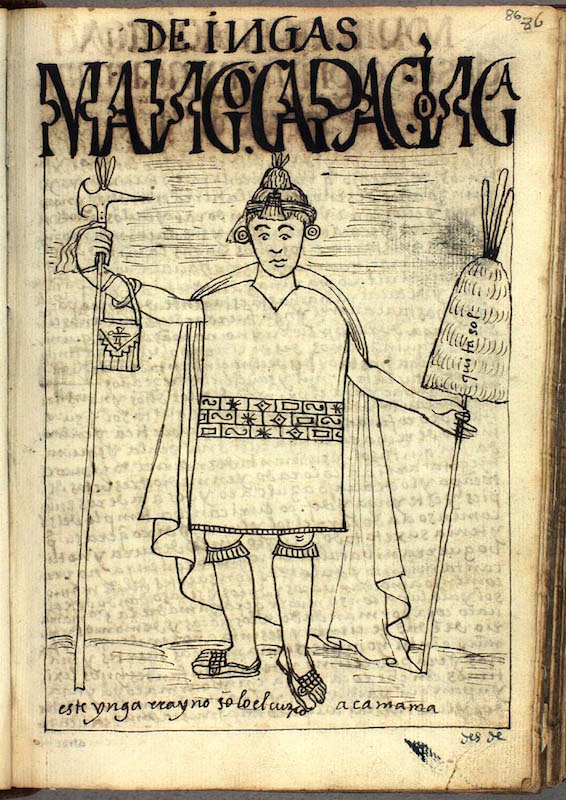

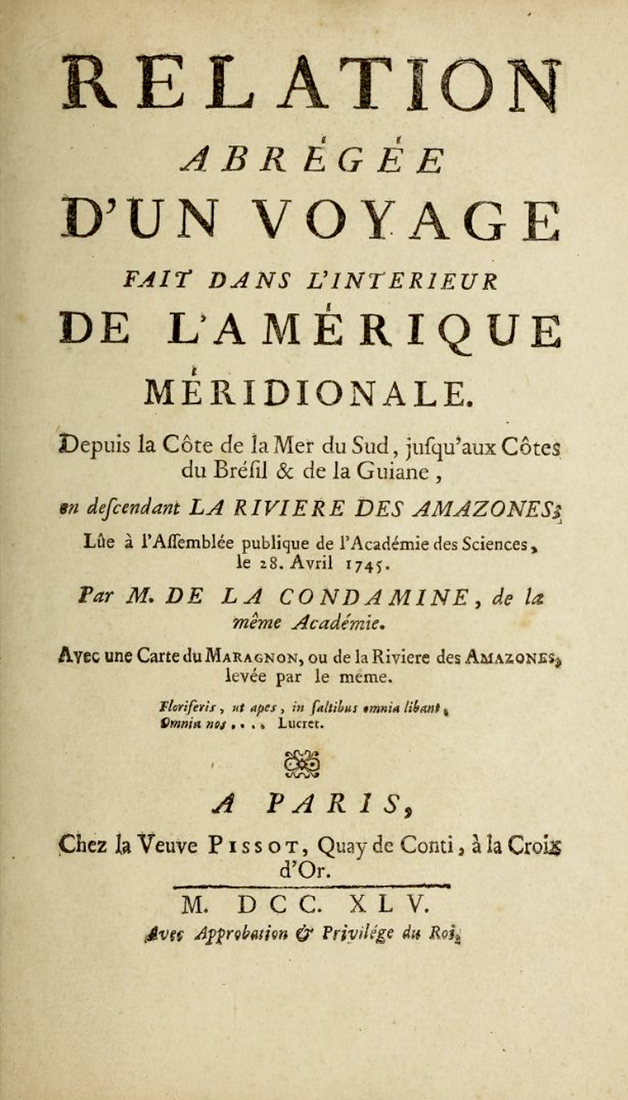

If you love to write letters, imagine writing one that is almost 1200 pages—complete with 398 full-page illustrations. Sound ambitious? Well, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, the indigenous Andean man, don Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, actually wrote such an extensive letter in pen and ink addressed to the Spanish king (at one point Philip II, and then Philip III). It was called The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615). Guaman Poma wrote about Andean peoples prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 1530s as well as documented the current colonial situation (“Andean” refers to the Andes mountains, in what is today Peru). He was keen to record the abuses the indigenous peoples suffered under the colonial government, and hoped that the Spanish king would end them. Guaman Poma hoped to have New Chronicle printed when it arrived in Europe, and for this reason he borrowed from type-setting conventions when writing the textual inscriptions accompanying his illustrations, such as those on the frontispiece to his letter (above). It also explains why he left his images in black-and-white.

While the first part of the manuscript addresses Andean life and culture prior to the invasion of the Spaniards, the second half focuses on viceregal life and administration (viceregal refers to the administrator who ruled the Spanish colony in the name of the king from the Conquest of 1534 until independence from Spain in 1820). For the viceregal section of the letter, Guaman Poma discusses topics as broad as parish priests and local native administrators to religious and moral considerations and viceregal towns and cities. So New Chronicle is not only ambitious in length, but also in scope!

Significance

This amazing letter is special for several other reasons. First, it is the most famous manuscript from South America dated to this time period in part because it is so comprehensive and long, but also because of its many illustrations. Few illustrated manuscripts survive from this time period, and Guaman Poma’s has no rival. Second, it is important for what it tells us about pre-Hispanic Andean peoples, especially the Inka. While the Inka had an advanced recording system that used knots on cords, called khipus, researchers have not yet been able to translate them. Guaman Poma’s discussion of Inka culture provides us with information that would otherwise be lost to us, even if we have to be aware that he wrote this information a generation after the Spaniards defeated the Inka. Finally, the letter is written in Spanish, two indigenous languages (Quechua and Aymara), and Latin—highlighting the various languages Guaman Poma knew. One might even consider the many images a fifth, purely visual language, one that combined Andean and European systems of representation.

A brief biography of Guaman Poma

Born around 1525, Guaman Poma was a descendent of the royal Inka on his mother’s side and the pre-Inka Yarovilka dynasty on his father’s side. He had a half-brother, Martín de Ayala, who was a mestizo (meaning that one of his parents was Spanish) and worked as a priest, eventually converting Guaman Poma’s family to Christianity. He claims that his brother also taught him to read and write.

Because he could read and write in several languages, Guaman Poma worked as an administrator and scribe in the Andean colonial government. On several occasions he attempted to have lands near Huamanga (today, a province in Peru), which were at the center of a dispute, returned to his family. Ultimately, he was exiled from Huamanga after he was charged with falsely claiming he was a noble entitled to these lands.

Guaman Poma also worked with the Mercedarian friar, Martín de Murúa, who had traveled from Spain in the 1580s to Peru to help convert the native peoples of the Andes to Christianity. Murúa completed two different historical chronicles, which included color illustrations, the Historia general del Piru (General History of Peru) and the Historia del origen y genealogía de los reyes Incas del Piru (History of the origin and genealogy of the Inka Kings of Peru, 1590. Guaman Poma completed some of the images in the manuscript known as the Galvin Murúa—attesting to the productive working relationship between these two men (despite Guaman Poma expressing some dissatisfaction with Murúa in his New Chronicle). A distinct advantage of working with Murúa, however, was that it afforded Guaman Poma access to his library—influencing some of the information and drawings contained in his letter to the King.

Guaman Poma the artist

Guaman Poma’s illustrations offer insight into his perception of the Andean past and colonial present. They don’t simply duplicate the text, but often complement it. Throughout his letter, Guaman Poma’s drawings pay scant attention to the details of individual faces, though he does render detailed clothing. For example, some of the most famous illustrations from New Chronicle are those depicting the male Inka rulers (called the Sapa Inka).

The image of the first Sapa Inka (above), called Manco Capac, shows the ruler standing in the center of the page, dressed in the appropriate regalia for a Sapa Inka. He wears a man’s tunic, called an unku, that has an elaborate, decorative band around his midsection. This is the tocapu, and it is reserved for the Inka ruler as a way to identify him and signal his special status. Manco Capac also wears elaborate sandals, earspools, and a special fringed ornament on his head, called the mascaypacha (and only worn by the Sapa Inka). A cape frames him from behind, and he holds a special staff and a weapon in his outstretched arms.

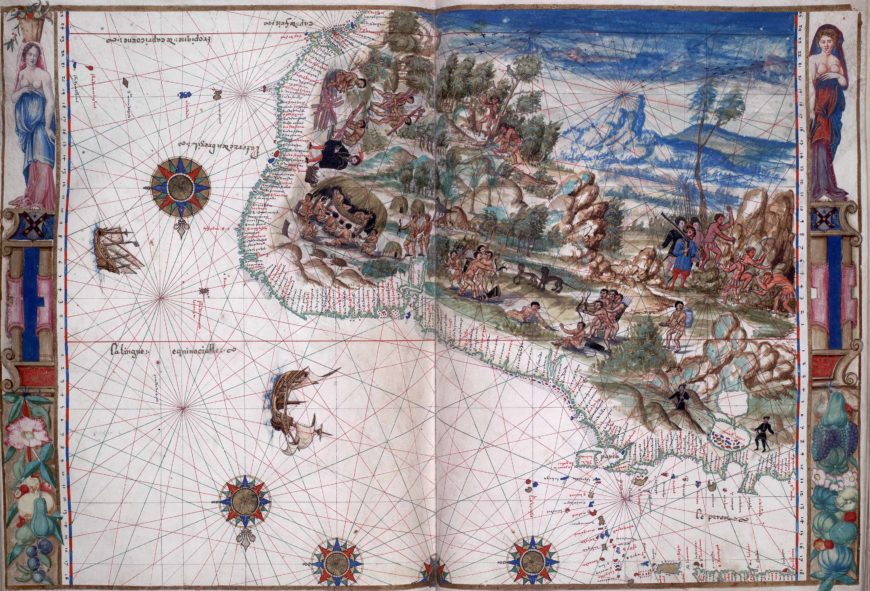

Maps

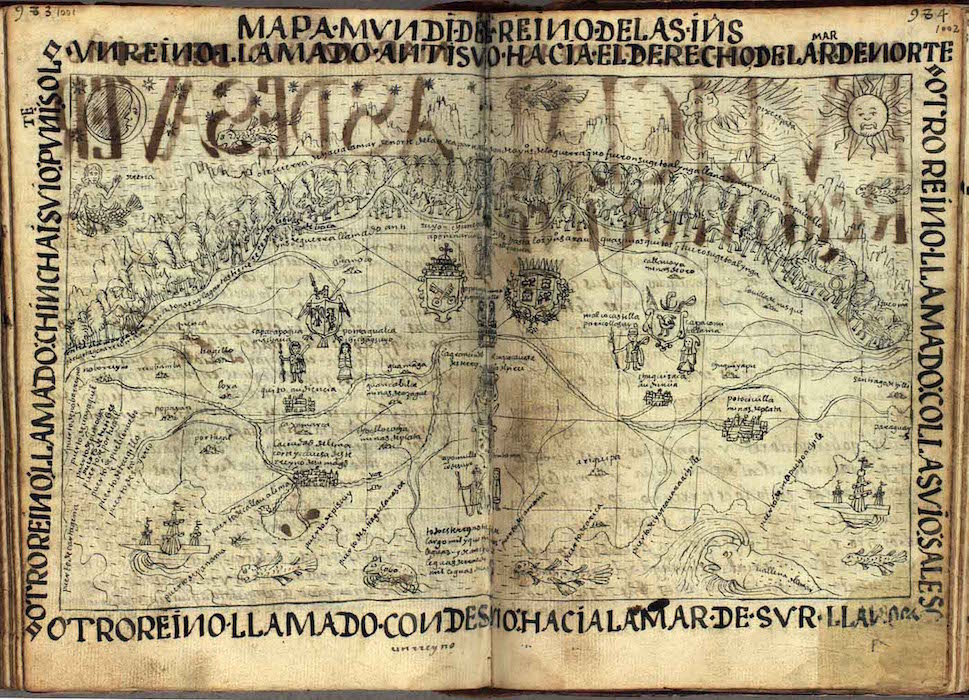

One of the most fascinating images from the manuscript depicts what Guaman Poma titles a “mappa mundi of the kingdom of the Indies” in other words, the Andean region (mappa mundi means “map of the world”).

Guaman Poma’s map shows the Andean “Indies” divided into four parts, with the Spanish Crown’s coat of arms and the papal (Pope’s) coat of arms at the center. The four parts of the world are based on the earlier Inka division of their empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, or realm of the four quarters. Each realm had a different name, and was associated with specific ethnic groups. In Poma’s mappa mundi, we see each region represented by a male and female couple, along with a coat of arms representing the quarter. Important cities are labeled, along with rivers and mountains.

For example, in the realm to the left of center, known as Chinchaysuyu, we see the Audiencia of Quito (an administrative unit in the Spanish Empire) labeled just below the ruling couple (left). Fantastic beasts like unicorns, monkeys, hairy men, and creatures reminiscent of dragons and large flying fish, dot the fringes of the land. A mermaid waves below the moon on the upper left corner. While some of these spatial conventions and fantastical creatures borrow from medieval European mapping traditions, Guaman Poma blends them with Andean concepts of space and symbols.

The Symbolism of Space

Throughout his manuscript, Guaman Poma uses space to communicate Andean notions of power—specifically the complementary concepts of hanan (upper) and hurin (lower). The mappa mundi offers a nice example of these concepts. The couple in the center is the Sapa Inka Tupac Yupanqui (an early Inka king) and his coya (queen consort) Mama Ocllo (who was also his sister). The suyus, or regions, of Chinchaysuyu and Antisuyu represent hanan (upper) positions, while Cuntisuyu and Collasuyu are hurin (lower). While the hanan regions are considered superior, they also complement the lower regions. Neither could exist without the other, and represent broader binary yet complementary concepts like male/female or left/right. Another example of this complementary relationship between hanan and hurin can be seen in the plan of the Inka capital Cusco.

Guaman Poma uses these spatial concepts in other ways in his manuscript—sometimes to draw attention to someone’s importance. For instance, on the frontispiece of the manuscript (top of page) the pope is in the hanan position (reader’s left, but right side of the page), while the Spanish king and Guaman Poma are in the hurin position. In this way, Guaman Poma likely intended to convey the superiority of the Pope.

The Conquest, Civil War, and Revolts

In chapter 19 of New Chronicle, Guaman Poma recounts the Spanish Conquest and ensuing civil wars that erupted in the Andes. The images accompanying the text reveal the Spanish lust for gold and some of the key events of the Conquest.

In one we see the Spanish conquistadors Francisco Pizarro and Diego Almagro, dressed in Spanish armor and leading troops (p. 373). Another image (above) shows the same conquistadors as they interact with Guaman Poma’s father, Don Martin de Ayala, who is noted as an ambassador to the Sapa Inka, Huascar Inka.

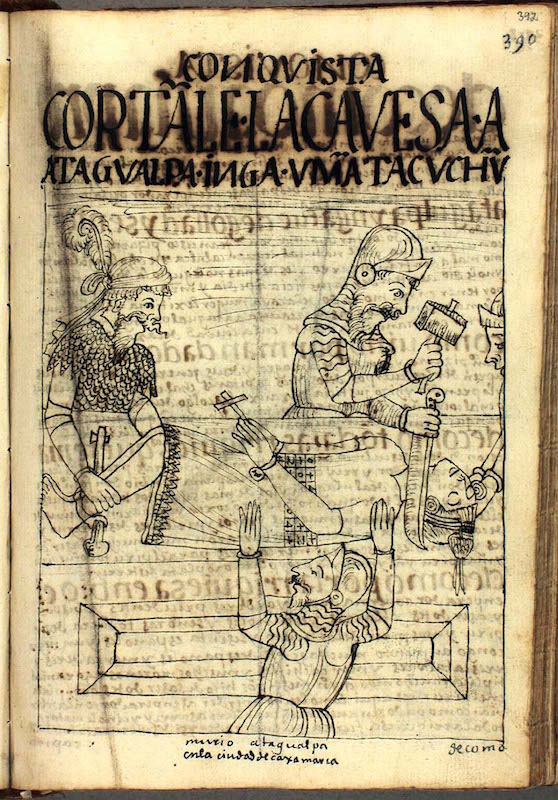

One of the most disturbing scenes of the Conquest is the beheading of Sapa Inka Atahualpa in the city of Cajamarca (above). Huascar Inka and Atahualpa were brothers who both sought to control the Inka Empire after their father died. Eventually, Atahualpa would defeat his brother during a civil war, and Atahualpa would then be captured by Pizarro. The illustration of Atahualpa’s execution shows him bound on a hard surface, his hands clasping a cross—a reference to his conversion to Christianity just prior to his death. A Spanish soldier holds a knife to his neck, as well as a mallet. Atahualpa’s eyes are closed, signaling that he is dead. The illustrations from this chapter portray the complexity and chaos of this time.

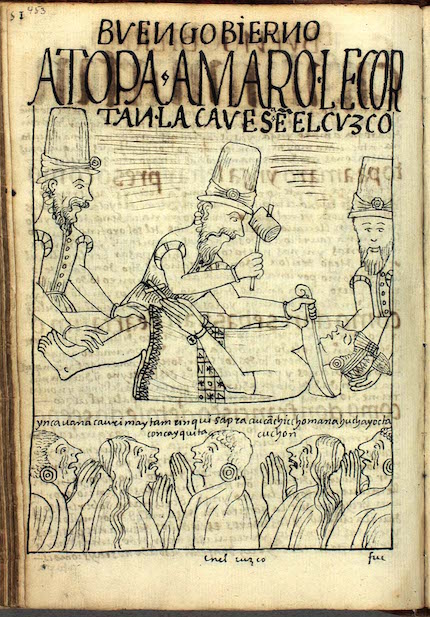

The following chapter details “good government” after the Spanish Conquest. In one illustration, we see the capture of Tupac Amaru Inka (p. 451), who led a series of revolts against the Spaniards as he and others attempted to retain an Inka state or empire free of the Spaniards.

Another image (left) shows Tupac Amaru’s execution in 1572, which mimics the death of Atahualpa Inka during the Conquest. Guaman Poma used the same basic composition and motifs, but this time with Tupac Amaru’s prone body resting above a group of weeping Andean peoples to highlight their suffering.

Tupac Amaru’s death is considered the end of the Conquest though he would remain a symbol of protest and revolt in the Andes throughout the colonial period, specifically the uprising led by Tupac Amaru II in the eighteenth century. (Fun fact: the hip-hop artist Tupac Shakur was named after Tupac Amaru II).

It is impossible to discuss all aspects of Guaman Poma’s Chronicle, but hopefully this essay provides a sense of the importance of his letter as a resource for learning about Inka and colonial Andean culture. While it never made its way into the hands of the Spanish king, and was never published and distributed as Guaman Poma intended, today the manuscript is available in its entirety online from the Royal Library of Denmark, where the original Chronicle is kept.

Additional resources:

A facsimile of the Historia general del Piru (also called The Getty Murúa)

Essays on The Getty Murúa from the Getty Museum

Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma: Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000).

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, trans. Roland Hamilton (Austin: University of Texas PRess, 2009).

Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author (NYC: Americas Society, 1992).

“Bad Confession” in Guaman Poma’s The First New Chronicle and Good Government

“The Bad Confession”

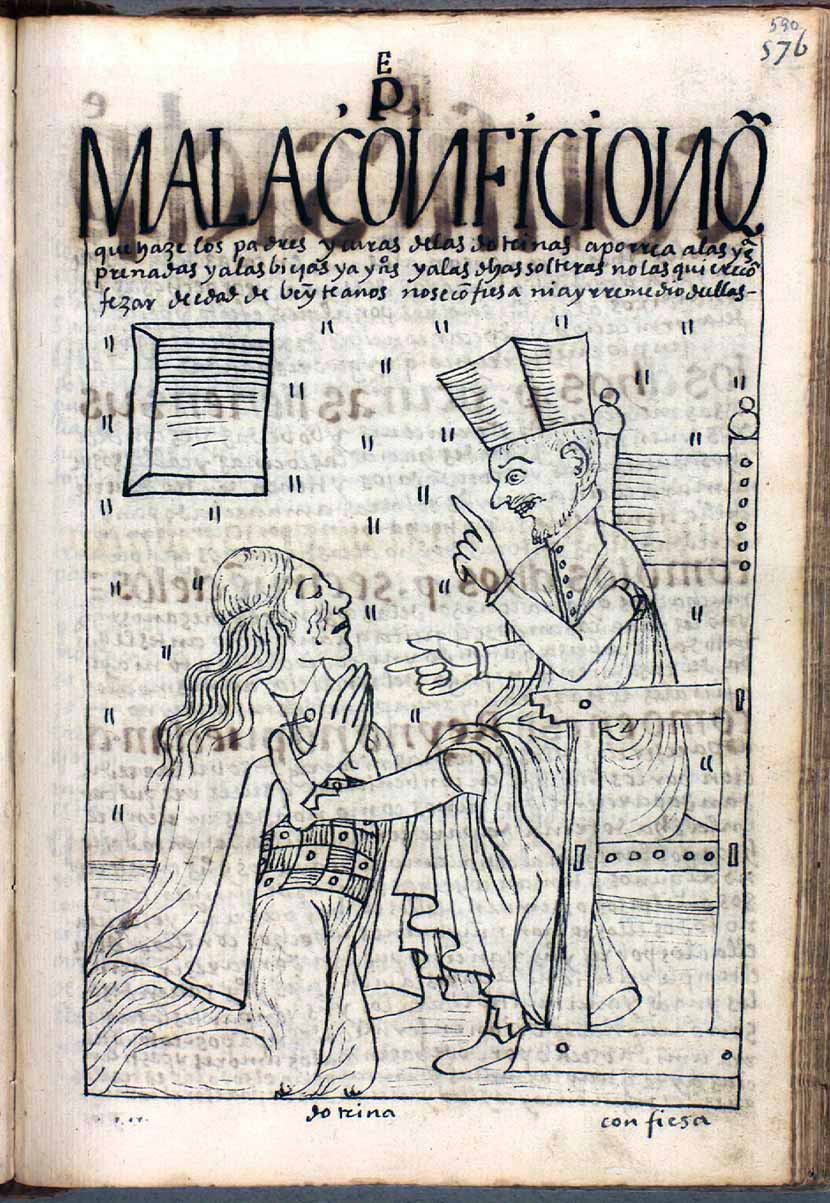

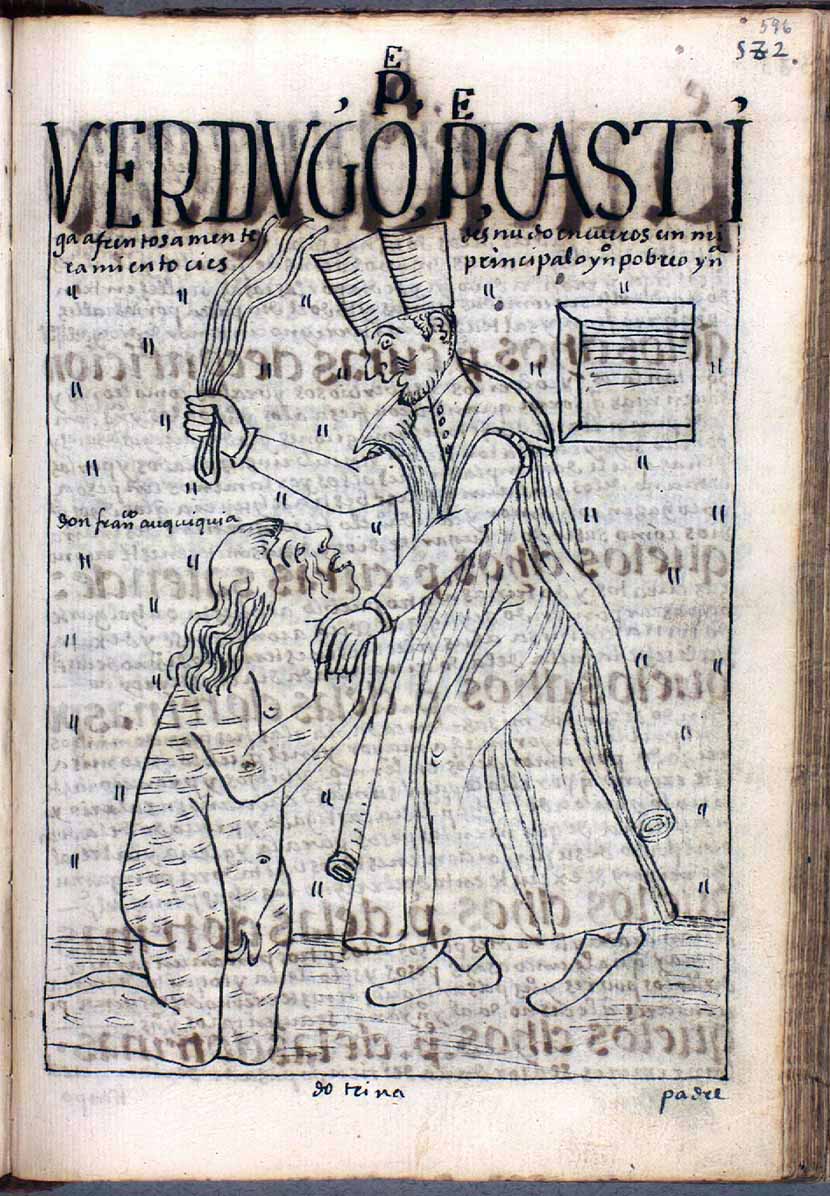

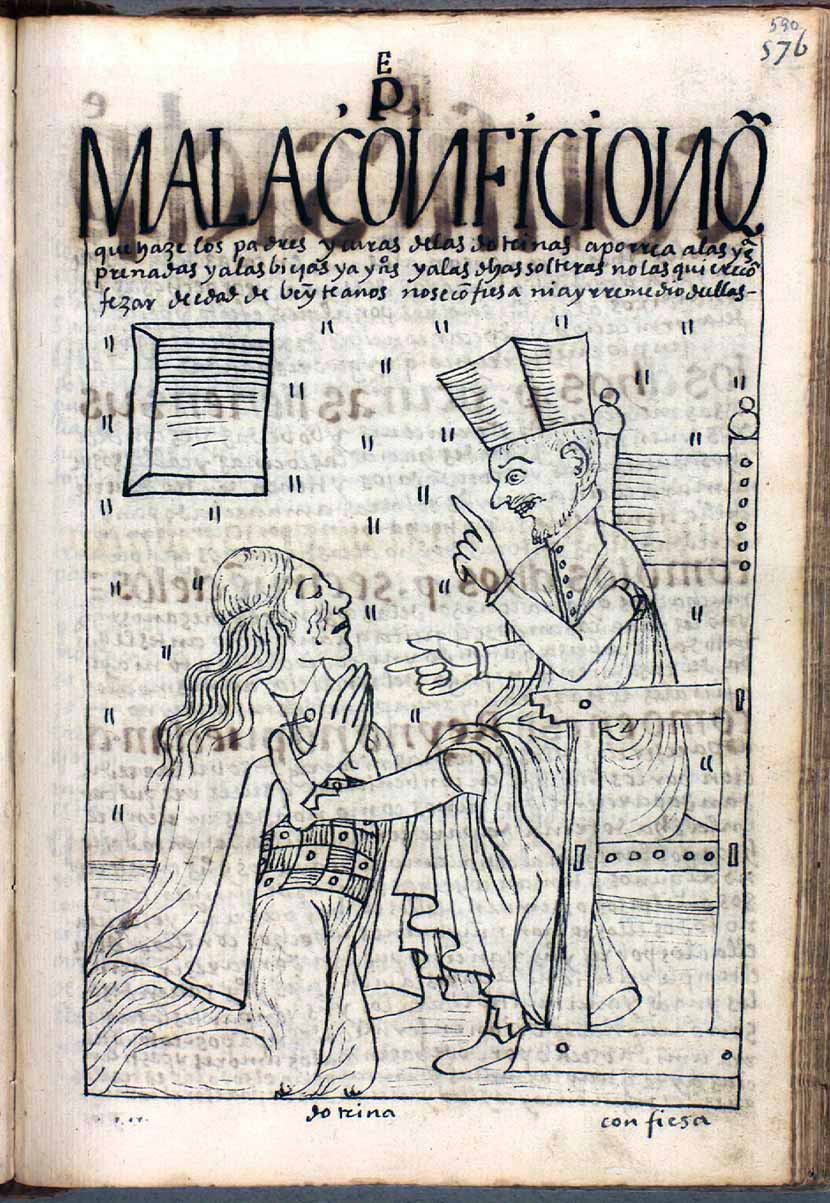

An Andean woman kneels with her hands clasped in prayer. Her indigenous identity is conveyed by her style of dress; she wears a lliclla (shawl) fastened with a tupu (garment pin) that opens to reveal tocapu-like designs on her dress underneath. She looks up at the priest, with tears in her eyes, as he rams his left foot in her abdomen. The violent image becomes all the more poignant on closer inspection of her swollen belly, indicating the woman’s pregnancy, which is described in the accompanying text.

This image, entitled “The Bad Confession,” is in Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s illustrated manuscript, known the The First New Chronicle and Good Government (El primer nueva coronica i buen gobierno), dated to around 1615. The first half of Guaman Poma’s illustrated manuscript provides a comprehensive description of Inka imperial history as well as an encyclopedic account of life under Inka rule, covering topics as diverse as the ritual calendar, agricultural practice, religious beliefs, different ways of burying the dead, and the various professions of the empire’s inhabitants. The second half of the manuscript details the abuses committed by the Spaniards during the early period of colonial rule in the Viceroyalty of Peru. Guaman Poma’s vivid imagery provides some of the only surviving visual sources that reveal the often violent treatment that indigenous people endured under their Spanish rulers.

“The Bad Confession” image participates in a larger visual and textual argument about the ability for native Andeans to rule themselves without Spanish intervention. Indeed, Guaman Poma presents the colonial period as a “Pachacuti,” a Quechua term that he uses to refer to a world turned upside down. As part of his plea to King Philip III, Guaman Poma strategically argues that Christianity existed in the Andes long before the Spanish invasion and that it is the Spaniards who are the exemplars of “bad Christians.” The visual mechanics of “The Bad Confession” support this thesis.

Hanan and hurin

The drawings in The First New Chronicle and Good Government often correspond to the Andean spatial hierarchies of hanan and hurin. Hanan is associated with dominance, masculinity, and superiority while hurin holds the connotations of weakness and femininity. [1] Within an Inka context, hanan and hurin were not conceived as occupying dichotomies of superior and inferior but were instead considered complementary relationships bound through systems of reciprocity. In this new colonial context, however, Guaman Poma has strategically deployed these concepts to highlight the depravity of the Spaniards.

In “The Bad Confession,” the woman occupies the hanan part of the composition (the internal right) while the priest is situated in the hurin segment (the internal left), thus displaying the moral superiority of the Andean woman, who is inflicted with physical violence in her most vulnerable region. In this “world upside down,” the priest, the supposed embodiment of morality, succumbs to a morally reprehensible act.

Illustrated manuscripts in early colonial Peru

There only exist three known illustrated manuscripts produced in early colonial Peru: two versions of Mercedarian friar Martín de Murúa’s account, separately titled History of the Origin and Royal Genealogy of the Inka Kings of Peru (Historia del origen y genealogía real de los reyes ingas del Perú, c. 1590–1615) and History of Peru (Historia del Pirú, 1616). The latter, which contains thirty-eight stunning watercolor illustrations depicting the lives of the Inka nobility, has recently undergone extensive conservation at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. The third and most well-known of the three is Guaman Poma’s New Chronicle (1615). The dearth of Peruvian manuscripts stands in stark contrast to the 1,000+ illustrated manuscripts that survive from colonial Mexico. The likely reason for this is because there did not exist a manuscript tradition in the pre-Columbian Andes as there did in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. The notion of drawing images and writing on paper had no precedent in the Andes until the arrival of the Europeans.

Nevertheless, these three manuscripts offer a compendium of Andean life both before and after the conquest of the Inkas. The wealth of information they provide has been of critical importance to archaeologists, historians, art historians, and anthropologists as a means to understand Inka history as well as the lived experience of indigenous peoples in the early years of Spanish colonial rule.

Notes:

[1] See Mercedes López-Baralt, “From Looking to Seeing: The Image as Text and the Author as Artist,” in Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author, ed. Rolena Adorno et al. (New York: Americas Society, 1992), pp. 14–31.

Additional Resources

A facsimile of the Historia general del Piru (also called The Getty Murúa)

Essays on The Getty Murúa from the Getty Museum

Scientific Investigation of Martín de Murúa’s Illustrated Manuscripts (Getty)

Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma: Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000)

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, trans. Roland Hamilton (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009)

Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author (NYC: Americas Society, 1992)

Lisa Trever, “Idols, Mountains, and Metaphysics in Guaman Poma’s Pictures of Huacas,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 59/60 (2011): 39–59.

The Church of San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): The Church of San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, 1570-1606, stone, adobe, kur-kur, Andahuaylillas (Peru)

Additional resources

Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, Church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas

The Sistine Chapel of the Americas

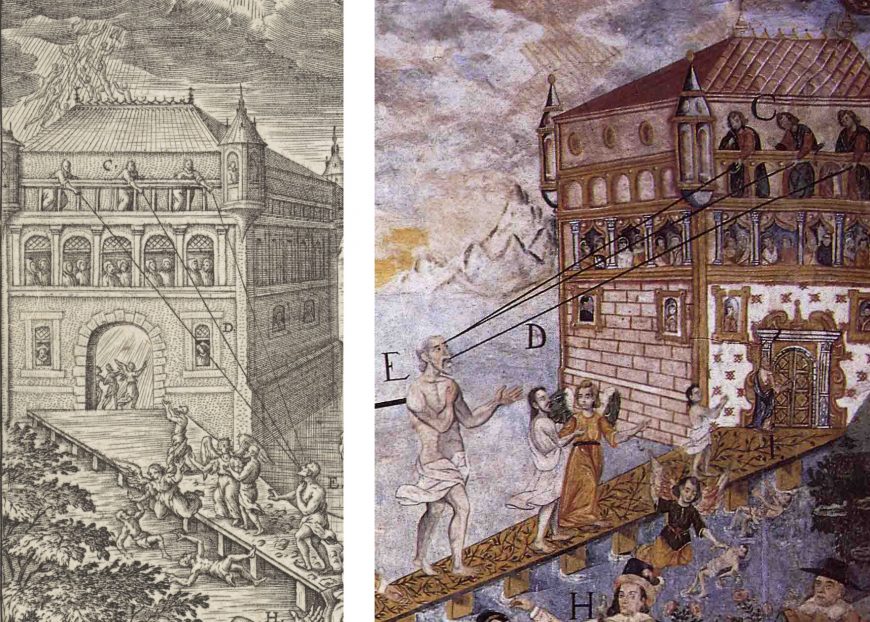

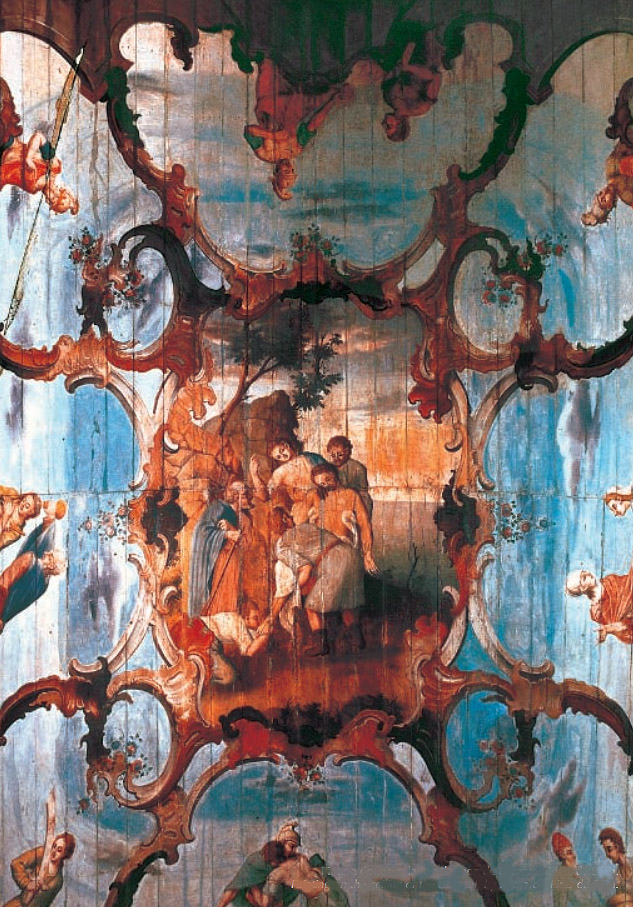

The Church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas located outside of Cuzco contains an expressive decorative program that has earned it the title of the “Sistine Chapel of the Americas.” Filled with canvas paintings, statues, and an extensive mural program, the level of artistry and extravagance afforded to this church certainly rivals its counterparts in Renaissance Italy.

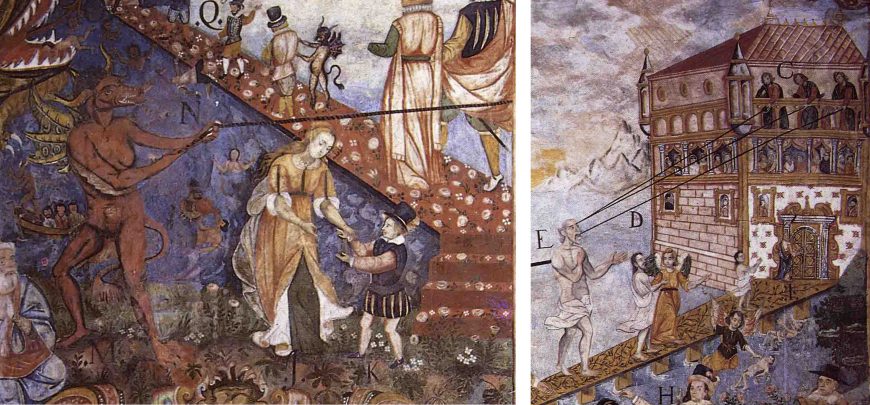

One of the church’s most well-known images is the mural painted on the interior entrance wall depicting an allegory of good and bad faith.

The subject matter

Painted by the criollo artist Luis de Riaño and indigenous assistants, The Paths to Heaven and Hell transmits an important message to parishioners as they exit the church of the moral decisions they will confront on their spiritual journey. The two paths refer directly to a biblical passage which states,

Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it / But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.

Matthew 7:13–14

A nude figure wearing nothing but a white sheet around his waist walks cautiously down the narrow and thorny path to the Heavenly Jerusalem, with three lines emanating from his head that lead to a representation of the Holy Trinity as three identical male figures. A thick rope also connects his back to the composition on the left of the doorway, where the Devil attempts to pull him over to the left side.

At the foreground of the scene is a banquet attended by four individuals feasting on wine, fish, bread, pie, and fruits. A mouth of Hell rears its head to the left of the path to Hell, its mouth agape with a naked sinner falling into his maw.

At the forefront of the scene is an allegorical female figure guiding a young man standing directly below the rope held by the devil. The path culminates at a castle engulfed in flames guarded by deer poised on the roof with bows and arrows.

The paths to Heaven and Hell were familiar tropes in medieval Christianity, with frequent representations in paintings, manuscript illuminations, and stage sets. Despite its decline in popularity in Europe by the Renaissance, this type of allegorical imagery carried great import in the colonial Andes.

The didactic iconography, painstakingly labeled with relevant biblical passages, was ideal for preaching Catholic doctrine to Andean parishioners. In fact, it is highly likely that Juan Pérez Bocanegra, the parish priest who commissioned the murals and accompanying decorative program, would have conducted his sermons using the murals as a focal point.

A New Jerusalem in the Andes

The mural is based on a print by Hieronymus Wierix entitled The Narrow and Wide Path, which Riaño copies relatively faithfully. One significant modification, however, can be found in the depiction of the path to Heaven. In the mural version, Riaño has added an additional figure at the doorway to the Heavenly Jerusalem holding a key. This individual likely represents Saint Peter the Apostle, the patron saint of Andahuaylillas. As the universal head of the church, Saint Peter held the keys to the kingdom of Heaven. Parishioners were thus given the implicit message that the church of their very community constituted a New Jerusalem on Andean soil. Indeed, the act of entering and exiting the church left congregations with a palpable reminder of the spiritual pilgrimage necessary for attaining salvation—and one that could be understood within the immediate parameters of their existence rather than as a place only to be visualized and imagined.

The path to Hell also contains an intriguing detail that is only visible upon close inspection of the mural. Three barely visible figures are seated in a devil-driven canoe beneath the mouth of Hell. The central figure wears an Inka-style tunic with a checkerboard pattern around the collar. Such regalia would have been worn by curacas, or local indigenous leaders. Another nearby indigenous figure ingests liquid from an Inka-style aryballos vessel called an urpu, probably filled with chicha. The figures differ dramatically from the rest of the mural in both content and style. They are painted using rougher strokes, indicating the hand of an assistant to Riaño. Moreover, the cultural specificity of the figures, linking them directly to the Inka past through objects and regalia, suggest that the assistant was of indigenous background.

Despite the obvious visual conflation of Andean ritual practices in association with the Christian concept of Hell, these figures were granted visibility in a religious arena that sought to eradicate Andean ancestral cultures. The Paths to Heaven and Hell infuses Christian iconography with local referents to facilitate a more personalized and culturally meaningful point of access for the seventeenth-century parishioners of Andahuaylillas.

Additional resources:

Ananda Cohen-Aponte, Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes (University of Texas Press, 2016)

More about the paintings in San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas

San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas at the World Monuments Fund

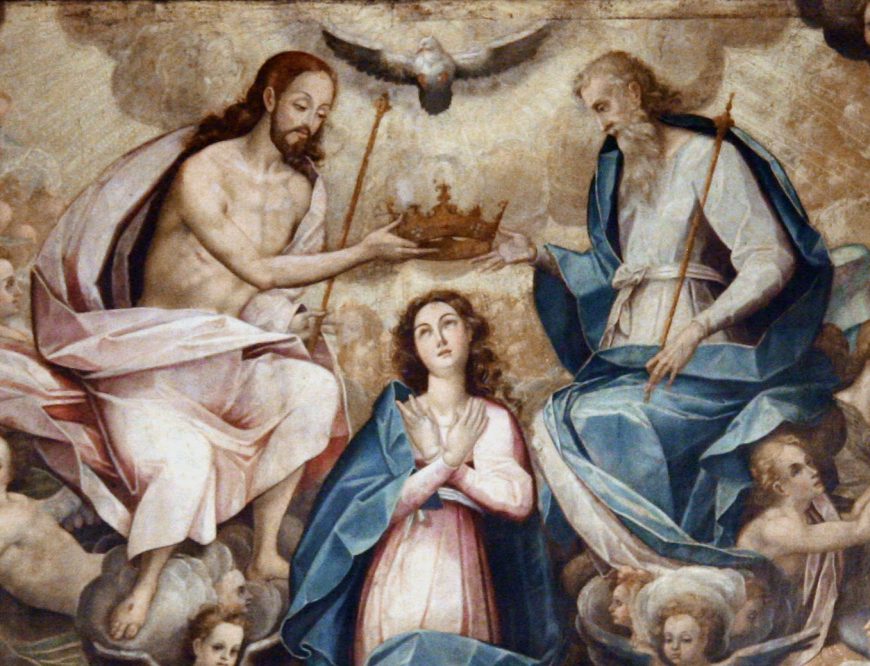

Bernardo Bitti, Coronation of the Virgin

European-style paintings in colonial Lima

In the Peruvian city of Lima, a visitor will encounter a bustling modern city, the natural beauty of the coast, and numerous references to the city’s layered past, including the ruins of structures made by indigenous cultures, and churches built during the colonial period. Filling those churches are paintings and sculptures that call to mind a tradition not born in South America, but in western Europe — that of the Renaissance, with its illusionistic devices, technical virtuosity, and figural narratives. Some of these paintings (along with books and prints) were imported from Spain, Flanders, and Italy. Some were painted by émigré artists resident in Lima. But why were European artists making paintings in colonial Lima?

Bernardo Bitti was one of many artists who made the journey across the Atlantic in this period as part of the Spanish Crown’s effort to colonize and evangelize the indigenous populations of what is today Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America. Bitti was a sixteenth-century artist from Camerino, Italy, in the Marches region, who produced paintings for churches throughout the Peruvian viceroyalty. He arrived in Lima, the viceroyalty’s capital, in 1575. Looking at Bitti’s work in Peru offers an opportunity to better understand the practice of evangelization. It also helps us to recognize that what we consider as Italian Renaissance art was not just a European phenomenon, but a global event.

An international Renaissance

The year 1492 is firmly planted in the western consciousness, as the fateful year that Christopher Columbus accidentally landed in Santo Domingo in what is now called the Dominican Republic. It also happens that this thing we call the Renaissance, an influential period of artistic and cultural achievement, took place contemporaneously, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. What then happens when we begin to consider this period of art making in correspondence with the beginnings of international encounters? The resulting collisions of belief, history, and art allow us to consider the period as one that was not localized in places like Italy and Flanders, but was in fact international in its scope.

The Coronation of the Virgin

Bitti’s first project in Lima was a large altarpiece depicting the Coronation of the Virgin, for the Jesuit Church of San Pedro. The subject matter is fairly straightforward, an image of the Virgin Mary rising into the heavens, to be crowned by Christ to her right, God the Father to her left, and a dove representing the Holy Spirit overhead, while angels playing musical instruments gather in celebration.

![Diego Valadés, Rhetorica christiana : ad concionandi et orandi vsvm accommodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis, 1579](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/friar-preaching-870x1284.jpg)

The painting would have been an important opportunity for the Jesuits to offer an appropriate representation of Christian doctrine to a potentially diverse audience of Lima’s citizens, which would have included viewers of many cultural backgrounds. Due to the diversity of the audience and the language and faith barriers between them, missionaries in Latin America relied on European imagery as tools for communication. In an image from Diego de Valades’s Rhetorica Christiana, printed in 1579, a Franciscan friar stands at a pulpit preaching, while simultaneously pointing to images displayed around the space to illustrate his points.

The context of the Counter Reformation

Bernardo Bitti was a painter, but also a Jesuit, who traveled to Lima as part of the order’s evangelization efforts. The Jesuits were at the forefront of global missionary efforts during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Issues and ideas from Europe intersected with the agenda of missionaries in Latin America. Throughout colonization, the Catholic Church remained embroiled in the Counter Reformation, a campaign to reinvigorate the Church and reform, where necessary, after suffering the criticisms of the Protestant Reformers in Northern Europe. Bitti’s Coronation of the Virgin did contribute important narrative information about Christian belief, but it also served as visual propaganda of the Catholic Church’s reform.

There are several elements to this painting that highlight Bitti’s attention to the Counter-Reformation agenda. Most important is the glorification of the Virgin Mary. The painting serves as a reminder of her divinity and an encouragement to worship her as queen of heaven. In this period, the Catholic Church re-asserted its dedication to the Cult of the Virgin, partly in response to criticisms from the Protestant Reformers. Between 1545 and 1563, the Council of Trent (a meeting of Church officials, convened to address the crisis of the Reformation, and among many other proclamations), affirmed the value of worshipping the saints, and the Virgin Mary. The Council also instructed that sacred art was a valid and appropriate undertaking.

Bitti’s painting would have served as a Counter-Reformation example of how art should serve its didactic and devotional functions. It is clear and legible. The composition is symmetrical, with the most important figures easy to locate, and their significance over the other figures made clear by the attention paid to them by surrounding angels. Additionally, the painting represents the Virgin’s crowning, not by just Christ, or God the Father, but by the Holy Trinity, the inclusion of the white dove completing this all important triad. Bitti’s inclusion of the Trinity as three separate entities was a critical iconographic choice. European commentators were careful to instruct artists of this period to be clear in their depictions of the Trinity, never as three identical figures, or one body with multiple faces, but as an older man, a younger man, and a dove. For Bitti, painting in Lima for a diverse audience of Europeans and newly converted indigenous viewers, the accurate depiction of the Trinity would have been of particular importance.

Representations of the Trinity were potentially problematic in the Andes, where the indigenous populations had for centuries followed polytheistic religions. Christian missionaries sought to stamp out any residue of such pagan beliefs and traditions. A painting presented by Christian clergy of three beings, representative of God, could be confusing for the local indigenous converts. These same missionaries vehemently prohibited the worship of multiple gods.

The matter was further complicated when Europeans learned that some Andean religions pictured their gods in threes. For example, three statues of the god representing the Sun stood in Cuzco; Apointi, Churiinti, Intiquaqui were the father Sun, the son Sun, and the brother Sun. Upon learning of this predisposition for a conception of a trinity in the local indigenous religions, the clergy attempted to use this potential complication to their advantage. They preached the idea that the pre-Christian existence of a trinity was merely a precursor for the true Trinity that the indigenous populations were now learning about. For them, the truth had been laying in wait, but obscured, for centuries. Images of the Trinity would become common in Spanish colonial art as tools to engage the locals with a familiar image but ones that needed to be appropriately presented according to Catholic doctrine.

Bitti’s paintings were also tools implemented to aid in the imposition of western European culture onto the indigenous Andean people. Bitti’s figural, narrative, illusionistic style of representation was steeped in the traditions of Italian Renaissance aesthetics. It was informed by the concept of Leon Battista Alberti’s “painting as window,” which contrasted violently with the centuries old visual traditions of the Andes, where art tended to be more abstract, geometric, and not representational. So, while it was certainly important for Bitti to use his altarpiece to communicate Christian narrative appropriately, this painting was also a weapon used by the Europeans in their campaign to replace ancient Andean beliefs and culture with their own understanding of the world.

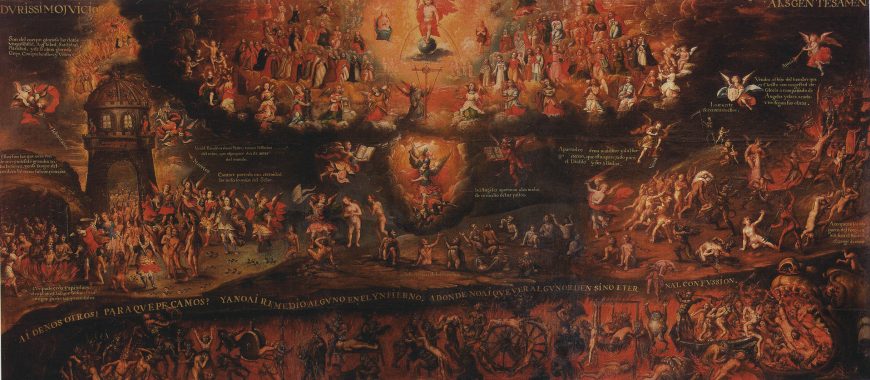

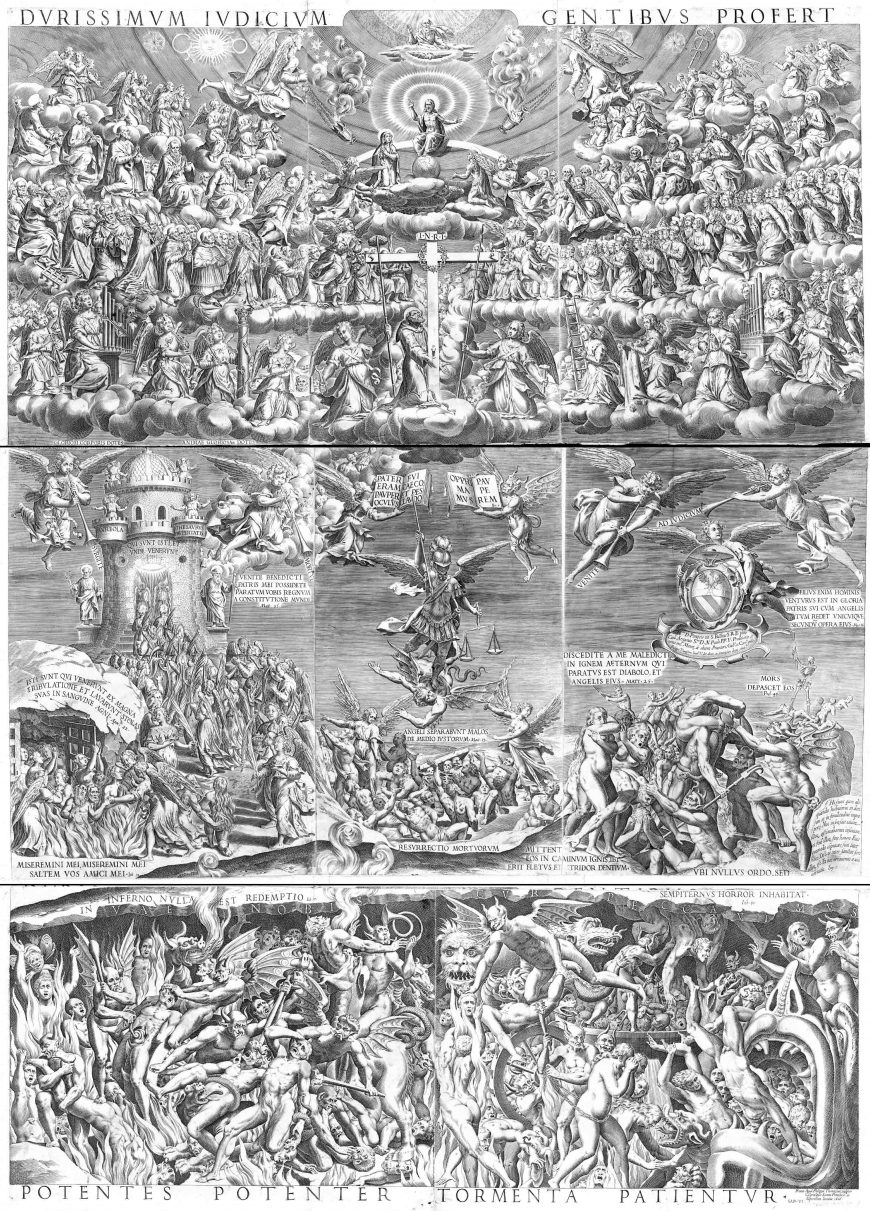

Diego Quispe Tito, Last Judgment, 1675

Indigenous Andean painters such as Diego Quispe Tito reinvigorated Cuzco’s artistic scene after the death of the Italian Jesuit painter Bernardo Bitti and other Spanish and Italian painters who traveled to the Viceroyalty of Peru in the late sixteenth century to establish their artistic careers. Quispe Tito imbued his compositions with powerful religious imagery that combined Italian, Flemish, and Indigenous pictorial traditions.

The end of time

His painting of the Last Judgment from 1675 located in the Convento de San Francisco in Cuzco provides an enduring reminder of the fate of humanity on Judgment Day. Sinners in hell depicted along the lower register of the composition receive an array of bodily tortures — we see individuals stretched across medieval breaking wheels, burning in bubbling cauldrons, and engulfed within the jaws of a Hell mouth. The souls in heaven (at the top), by contrast, surround the ascended Christ in an orderly formation.

Word and image

Quispe Tito’s canvas retains a strict tripartite scheme of Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell through the use of textual glosses to delimit the painting’s three compositional layers. The texts describe their accompanying scenes in vivid detail, thereby creating a strong interaction between linguistic and visual representation. The glosses add an additional layer of meaning to the image that would have been accessible only to the privileged few that were literate in Spanish. Nevertheless, the visual cues alone provide ample information about Christian eschatology (End of Days) for the purposes of instruction and evangelization.

![Diego Quispe Tito, detail, "there is no longer any remedy in hell, where there is no order to be had but [instead] eternal confusion" Last Judgment, oil on canvas, 1675](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Quispe-Tito-LJ-d3-870x113.jpg)

European models through prints

The Last Judgment is modeled from a 1606 engraving by Philippe Thomassin, a French-born engraver who spent the majority of his life in Rome. It remains unclear whether Quispe Tito had access to Thomassin’s original engraving or a seventeenth-century copy by the Flemish engraver Matthaeus Merian. Regardless of the precise source used by Quispe Tito, his Last Judgment reveals the importance of European models in colonial Andean painting, while at the same time demonstrating the creativity of seventeenth-century artists in determining the painting’s color palette and incorporating unique compositional details.

Christian themes related to the End of Days continued to preoccupy Andean patrons and artists throughout nearly the entirety of the colonial period. For example, the mestizo artist Tadeo Escalante produced a mural painting of the Last Judgment in 1802 at the church of Huaro located just outside of Cuzco.

Escalante’s and Quispe Tito’s compositions share the very same print source, despite being produced over a century apart. Escalante’s bright color palette and preference for flattened, simplified forms, however, signals a major turning point in colonial Andean painting that occurred shortly after Diego Quispe Tito completed his painting.

Additional Resources:

Ananda Cohen-Aponte, Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes (University of Texas Press, 2016)

Rodríguez Romero, Agustina & Siracusano, Gabriela (2010) “El pintor, el cura, el grabador, el cardenal, el rey, y la muerte. Los rumbos de una imagen del Juicio Final en el siglo XVII.” Eadem Utraque Europa 6 (nos. 10-11): 9-29.

Read more about the arts of the Spanish Americas

Learn more about engraved sources for paintings in colonial Andean art on Project on the Engraved Sources of Spanish Colonial Art

Parish of San Sebastián, Procession of Corpus Christi series

Worlds collide

Inka, Spanish, and Christian traditions come together in this 17th century painting of a religious procession in Cusco (in present day Peru). At the time, much of South America was a Spanish colony governed as a viceroyalty (a viceroy was someone who ruled as a representative of a monarch—in this case, the King of Spain). Cusco was part of the Spanish viceroyalty of Peru which lasted from the 16th to the 19th century. To make matters more complicated, Cusco was also the former capital of the Inka Empire.

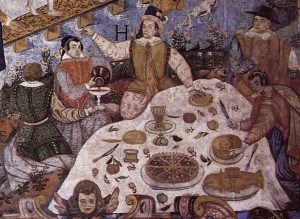

Parish of San Sebastián is part of a series of eighteen canvases (sixteen of which survive) that depict the religious festival of Corpus Christi in Cusco. These large paintings (they range from 6 feet square to 7 x 12 feet) were painted by at least two artists and were made for the Santa Ana parish church in Cusco, located in the Andes mountains.

The procession

Corpus Christi, meaning “body of Christ” in Latin, is a celebration of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation—the transformation of the wine and bread of the Eucharist into the actual blood and body of Christ. The religious processions that accompany this festival have been compared to ancient Roman triumphs, which generally celebrated military victories. The triumphal Corpus Christi processions celebrate Christ as victor and metaphorically allude to the triumph of Christianity over pagan religions (the Corpus Christi festival is still celebrated in Cusco today).

In the painting, we see the Eucharistic host (the sacramental bread) along with a statue of a saint, paraded along a processional path. A bishop on the far right (see image left) carries a monstrance containing the Eucharistic host (a monstrance is a vessel used to display the host). In addition to the bishop, other members of the San Sebastián parish community—including clergy members, government officials, and leaders of the indigenous Inka population—were included in the procession, while elite citizens of Cusco witness the procession from their windows. This annual triumphal procession signaled the dominance of Spanish colonizers over the indigenous population. Conveniently, Corpus Christi coincided with the Inka solstice celebration of Inti Raymi, or “Festival of the Sun,” leading to conflation of these festivities and aiding Christian conversion efforts.

In addition to the figures, we see a processional cart in the center, on top of which appears a statue of Saint Sebastian. These carts appear throughout the series and were based on structures used for religious processions in Spain celebrating the festival of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception. The carts resemble ships’ hulls and are modified from illustrations the artists in Cusco saw in a Spanish festival book (left). In this case, Saint Sebastian, who appears tied to a tree and pierced with arrows to represent his martyrdom, has replaced the Virgin Mary.

Leading the procession is an Inka kuraka who acts as a standard bearer (see bottom image). Also referred to as caciques, these local rulers of indigenous descent were granted privileges (cacicazgos) by the Spaniards and allowed to maintain a position of leadership after the Spanish conquest in the Andes. By the early-seventeenth century, twenty-four caciques held this hereditary office—making this an exclusive position. In exchange for their acculturation and adoption into the Spanish hierarchy, caciques were required to implement Spanish law among the indigenous population.

To maintain their status, it was necessary for caciques to prove their indigenous heritage. Caciques were often the subject of portraits that sought to authenticate their sitters’ political position. These images derive from traditional Spanish portraiture (the visual representation of rulers was not an established tradition in Inka culture). Cacique portraits, such as the Portrait of Don Marcos Chiguan Topa, included panels of text that referenced the subjects’ indigenous heritage. Additionally, elements of traditional Inka costumes were often employed to emphasize the caciques’ Indian-ness and therefore validate their positions as kurakakuna.

Caciques were sometimes depicted wearing tunics that evoke indigenous textiles through their intricate designs, as well as crowns that included a mascapaycha, a red-colored fringe that covered the forehead that was traditionally a symbol of Inka royalty. It was traditionally worn on the crown of the Sapa Inka (or “unique Inka,” the preeminent ruler during pre-Hispanic times). Breeches and long sleeves with lace were often added as traditional Spanish elements.

Costume: Inka + Spain

The cacique depicted leading the procession in the Parish of San Sebastián canvas wears an Inka tunic (uncu) with modifications to incorporate Spanish costume elements, like lace sleeves. The highly detailed garment, which includes a sun face on the front, is meant to indicate Andean nobility. The cacique’s crown also features a mascapaycha to distinguish his status. The crowns of the caciques depicted in the series were accompanied by other details such as feathers, flowers, birds, and rainbows. This particular mascapaycha in Parish of San Sebastian features a rainbow topped with a silver globe with feathers and banners, as well as two curiquenque birds, all typical of pre-Hispanic Inka noble insignia.