10.14: Conceptual + Performance Art

- Page ID

- 67853

Conceptual and Performance Art

The Modernists proposed that art could be anything—so why couldn't it be an idea or an action?

c. 1960 - present

Conceptual Art

Conceptual art can include just about any material: text, photography, found objects, and even the physical space of the gallery.

c. 1960 - present

A beginner's guide

Conceptual Art: An Introduction

by DR. TOM FOLLAND and DR. LETA Y. MING

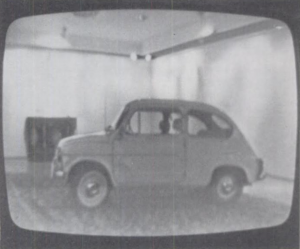

In 1972 the De Saisset Art Museum at Santa Clara University in the San Francisco Bay Area gave the artist Tom Marioni several hundred dollars to help cover expenses for mounting an exhibition of his work at the institution. Instead of using the money to purchase art materials, Marioni bought an older model used car, a Fiat 750, which he carefully maneuvered into the museum for the opening of his show. The vehicle, parked on top of an oriental rug, formed the centerpiece for this exhibition, titled My First Car. Was this really art, or was it a scam to get the museum to pay for a car the artist wanted? After learning about the show, the University President concluded that it was more of the latter and ordered the show closed. Presumably he was put off by how My First Car profited Marioni without involving any technical skill or hard work on the part of the artist.

Not just a prank

Marioni’s work was in many ways typical of the late 1960s and early 1970s art practices that came to be known as Conceptual art. As the term suggests, Conceptual art placed emphasis upon the concept or idea, and deemphasized the actual physical manifestation of the work. Thus an artist did not need manual skill to produce his work, and in fact could get away with not making anything at all. Rather than being a mere prank (as many dismissed it at the time), Marioni’s work was a proposal for a new kind of art that deliberately disavowed art’s traditional role as a showcase for the creative genius and technical abilities of the artist.

Marioni’s appropriation of a car is only one example of a number of very diverse art practices that are grouped under the term Conceptual art. Refusing to work in any one medium, and especially hostile to the painting and sculptural traditions in Western art, Conceptual artists would broaden their approach to art-making to include just about any material: text, photography, found objects, and even the physical space of the gallery, as long as there was a conceptual dimension that emphasized a set of principles or process involved in producing a given artwork, rather than a finished product.

Take the artist Mel Bochner’s Measurement Room, for example, a work that consisted of labeling gallery walls with numbers to indicate each wall’s dimensions. In the place of attractive objects and captivating imagery, Bochner presented emotionless, mechanical text overlaid onto a pre-existing space. Art’s new role, as proposed by Conceptual artists, was to convey information in the most straightforward, objective manner as possible and to engage the viewer within their immediate environment (instead of presenting a transcendent and imaginary world that accentuated the pleasures of looking).

Minimalism as precursor

Conceptual art constituted a dramatic departure from traditional art-making, but it did not come out of nowhere. Minimalism, the movement that directly preceded Conceptual art and the style that dominated the 1960s, conceived of art not as something internally complete and detached from the everyday world (a view that had been strongly held by the Abstract Expressionists throughout the 1950s), but rather as something that related to both its site of display as well as the viewer’s body. A Minimalist work like Carl Andre’s 144 Aluminum Square, for example, offered a spare, industrially-produced, geometric installation that was radical because it made spectators think of the floor on which it was placed and how their bodies related to it (by trampling on it!).

Emerging out of Minimalism, a Conceptual work like Bochner’s Measurement Room also made viewers aware of the proportions of the physical gallery space and encouraged them to compare how they measured up to the room’s dimensions. Minimalism, however, always maintained a reliance on a physical object, which was, in many cases, a highly finished and aestheticized form that lent itself to being traded on the art market and shown on gallery circuit. By contrast, Conceptual works like Measurement Room and My First Car not only departed from the conventional media of painting and sculpture, but moreover, their unusual forms prevented them from being easily sold or collected.

The art market

With the explosive expansion of the contemporary art market in the 1960s that included high auction prices for living artists (previously it was only dead European masters who fetched such prices), one of the main concerns of artists in the 1960s was that art had become increasingly commodified, and yet artists weren’t the ones benefiting from the growing market. At the mercy of dealers, collectors, and museum trustees, artists felt they had little control over their own work and careers. So it is not entirely surprising artists in the late 1960s and early 1970s began to reject technical artistic skill and material objects altogether. To make an object the essence of the artwork was to be in thrall to the concerns of the market and art institutions.

A radical era

The 1960s and early 1970s was tumultuous and divisive era defined by the Vietnam War, passionate social liberation movements (including the Black Power, Feminist, Chicano, and Gay Liberation Movements), as well as a massive countercultural youth rebellion. The emergence of such a radical practice as Conceptual art should be understood as part of this oppositional culture that envisioned a radically new world. To the new generation of Conceptual artists, the old rules of art making and the traditional art establishments could feel just as oppressive as the institutions of the state or police felt to the youthful protester on the streets.

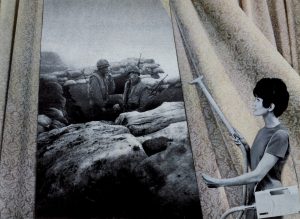

The backdrop of immense social upheaval in the 1960s and early 1970s relates to another important aspect of Conceptual art: the sense that it was entangled with larger social and political realities. In a series of collages called House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, Martha Rosler combined graphic images of the Vietnam War from the popular news journal Life with those of upscale interiors from the home decorating magazine House Beautiful to make direct reference to the Vietnam War.

In one collage, a middle-class housewife vacuums billowing drapes whose window reveals helmeted, rifle-wielding American soldiers in the trenches of war. This jarring juxtaposition not only commented on the war’s insidious effects on the home front, but also signaled a sense that art should engage with and could reshape the social world. Likewise, My First Car employed a similar technique of inserting a temporal, everyday object into a sacred space of high art in order to highlight the connectedness of the art sphere to the social, physical, and economic world. Not afraid to embrace the mundanity of the everyday world, Conceptual artists polluted the museum space with commerce, contemporary images of war, and even leaking motor oil.

Conceptual goes mainstream

Conceptual art had its precursors, notably early twentieth-century Dada artists like Marcel Duchamp, whose “readymades” (mass-produced objects like a urinal or bicycle wheel that he designated as artworks) also questioned the tenet that art be solely a demonstration of an artist’s creative and technical abilities. In the 1950s and early 1960s, movements such as Fluxus, Happenings, Neo-Dada, and Nouveau Réalisme also employed techniques we could categorize as Conceptual art from today’s vantage point. Embracing ephemeral and performative practices, and provoking viewers with sometimes aggressive assaults upon “good taste,” they, too, let go of the notion of art as refined object. In the decades following, Conceptual art strategies were taken up by feminist as well as postmodern artists, and today conceptualism has become a global phenomenon, with artists from around the world deploying video, photography, text, body art, performance, and installation, often interchangeably. Ironically, the strategies of Conceptual art, once a challenge to orthodox, mainstream modern art, have now become so fundamental that they are taken to be a given of contemporary art practice.

The Case for Conceptual Art

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Sometimes art is paintings, and sometimes it’s a chair. Why?

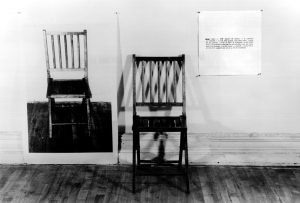

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs

You would not be wrong, standing in front of One and Three Chairs, to think, “there is not much to see here.” Joseph Kosuth, a conceptual artist, has placed a wooden folding chair against the wall and flanked it with two prints: a black and white photograph of the chair, and a photostat of its dictionary definition. Nevertheless, One and Three Chairs is a defining work of conceptual art, a movement that emerged in the mid-1960s and advocated a radically new form of artwork: one whose value, meaning and existence was rooted in its concept, rather than in the work’s physical or material properties.

In Minimalism’s wake

Questions of form (the visual elements of works of art) had been paramount for many modern artists during the twentieth century and especially post-World War II, when New York City replaced Paris as the center of the most advanced art of the time. Modernism’s focus on pure form (works of art that sought to contain no references or likenesses to the external world and focused instead on their own inherent visual and material aspects) reached a peak in the 1960s with Minimalism, the movement that directly preceded conceptual art.

Minimalism pushed abstraction to its limits and set out to strip art of its historical meaning. For instance, the Minimalist artist Donald Judd produced a series of geometric boxes using industrial materials. There was no evidence of skill or handicraft—the artist had in some cases not even constructed the object—and the viewer was left with no references to a subject or theme. The result was a work that was purely formal: that sought to insulate itself from external meaning beyond its material, color, and shape.

For the Minimalists, art’s role was no longer to render scenes of nature, spirituality, or humanity, as had been central to Western art since before the Renaissance, or even to celebrate the artist’s vision and hand as had been the case with Abstract Expressionism. The credo of Minimalist art was “what you see is what you see.” With these pure forms, art was emptied of all other meaning. It was as if the word “sculpture” needed quotation marks. It certainly strained credulity to imagine an industrially-fabricated object made from lacquered, galvanized iron as the equal to the historic sculptural processes such as carved marble or cast bronze produced by Donatello or Bernini.

“Art After Philosophy”

By the end of the 1960s, these Minimalist practices were being challenged. Minimalism’s value remained tied directly to the physical object—a visual form that invited viewers to see it, walk around it, and enjoy its aesthetic qualities. Conceptual artists like Kosuth wanted to downplay the pleasures associated with looking at art as part of a rejection of what they saw as outdated ideas about beauty. While retaining Minimalism’s critical stance toward traditional art forms, they wanted to engage with the unseen relationships that Minimalism had put aside: ideas, signification, and the construction of meaning. “Being an artist now means to question the nature of art,” Kosuth wrote in his 1969 essay “Art After Philosophy.” To this end, he created works that directed the viewer away from form and toward the ideas that generated them.

In the case of One and Three Chairs, the central idea was to explore the nature of representation itself. We know instinctively what a “chair” is, but how is it that we actually conceive of and communicate that concept? Kosuth presents us with a photograph of a chair, an actual chair, and its linguistic or language-based description. All three of these could be interpreted as representations of the same chair (the “one” chair of the title), and yet they are not the same. They each have distinct properties: in actuality, the viewer is confronted with “three” chairs, each represented and experienced—read—in different ways.

Semiotics

Kosuth was influenced by new theories of language and signification that had emerged in the early twentieth century, particularly semiotics—the study of the meaning of signs (words or symbols used to communicated information). Semiotics grew out of the science of linguistics, which looks at how language structures meaning. However, the field of semiotics had a broader set of goals: it sought to explore how both linguistic and image-based forms of communication shaped larger social and cultural structures.

Why photography and text, and not a painting or a sculpture? Kosuth’s avoidance of the traditional media was also a critique of the ways that art institutions had historically accepted and promoted only certain types of artworks. This criticality had roots in the radical Dada practices of Marcel Duchamp and other early twentieth-century artists who pushed for the acceptance of new forms of art. Artists from the 1960s onward were increasingly interested in building on this legacy, challenging the ways that museums, academies, and other art institutions adhered to traditional, nineteenth-century notions of what art was and should be.

The viewer’s role

When we look at One and Three Chairs, we are not drawn to admire its beauty, nor are we presented with a relatable story or a figure to be admired. Rather, we are invited to consider the concept of what a “chair” is, as well as the nature of visual and linguistic representation itself—fundamental questions that Plato asked more than two thousand years ago. And like the ancient Greek philosopher, Kosuth focuses on the idea of a “chair,” rather than simply its physical representation. But he also reveals the importance of the viewer’s role in the function of conceptual artwork. It is not until we approach pieces such as One and Three Chairs and begin to engage with them intellectually that the actual “artworks”—the concepts—emerge. In this sense, conceptual art can only exist in tandem with its audience, and is created anew each time we view it. This emphasis on the participation of the viewer was also important for the related movements of performance and participatory art, which gained momentum as well beginning in the 1960s.

One and Three Chairs stripped art of its outer casing and celebrated, instead, the importance of the conceptual for both the artist and the viewer. Importantly, it also stripped the artist of his or her role as a romantic and existential agent of personal expression (an aspect of art that was increasingly important from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century). The conceptual artist appears, instead, as a philosopher questioning the nature of reality and the social world in which art and audience reside.

Additional resources:

John Baldessari, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): John Baldessari, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, 1971, lithograph, 22-7/16 x 30-1/16″ (MoMA), images © John Baldessari, courtesy of the artist

Serious Humor

“I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art,” repeated in a neat cursive script down the length of a sheet of lined paper is clearly reminiscent of an old-fashioned school-room punishment. But just who is it that the artist, John Baldessari, is punishing? The lines are stark and simple, and like so much of John Baldessari’s art, employs a wry humor that turns on the art world, only in this case, the blackboard is a canvas.

Only a year earlier, in 1970, Baldessari underlined a key rupture in his career and one that was taking place in the art world as well at that time. Since the 1950s, Abstract Expressionism had been the dominant avant-garde style in galleries and art schools. For example, Jackson Pollock’s huge canvases, dense with paint he applied directly, were understood (however inaccurately) to be a direct expression of his internal emotional state.

Cremation Project

As a young artist, Baldessari had also painted abstractions. But in 1970, a year before I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, Baldessari, together with friends and students from University of California at San Diego, gathered paintings he had made as a young artist and drove them to a crematorium where they burned them. The artist then placed the ashes into an urn with a bronze plaque inscribed,

JOHN ANTHONY BALDESSARI

MAY 1953 MARCH 1966

The urn and plaque, together with documenting photographs of the cremation constitute Baldessari’s Cremation Project, 1970. The previous year, the artist had written of this project as an act to,

…rid my life of accumulated art….It is a reductive, recycling piece. I consider all these paintings a body of work in the real sense of the word. Will I save my life by losing it? Will a Phoenix arise from the ashes? Will the paintings having become dust become materials again? I don’t know, but I feel better.1

In Cremation Project, Baldessari defined the clearest possible demarcation between his early and mature work. By sacrificing his early paintings, by burning them, he emphasized their physicality. They existed as a thing in the world that could be destroyed. But he shifts our frame of reference from the physical, the material, by creating a work of art that relied on the physical artifact, the ashes and urn, only as a way to draw the viewer to the larger conceptual issues—including the construction of a division in his career.

With the Cremation Project, John Baldessari staked his place in the highly intellectualized space of 1960s and 70s conceptual art practice. By 1970, Conceptual art had established a place for itself in the art world. The stark machined repetitions created by the artist Donald Judd and the grids painted by Agnes Martin laid the groundwork for artists like Sol Lewitt who created written instructions for lines drawn with mathematical precision onto a wall to create dazzling geometries. Lewitt had created conceptual works of art that asked the Platonic question, where is the art itself actually located? Does it exist as the completed drawing on the wall? Does it exist in the originary act of writing the instructions? Is the art embedded in the performance of the work when assistants do the drawing? What happens when the wall drawing is painted over and is remade somewhere else? This was the world of ideas into which Baldessari entered.

Word Paintings

In Baldessari’s art, words, photographs and paint offer visual statements that are so flat, so bald-faced in their directness and sincerity that they become ironic visual statements aimed at the very definition of what art is. And because these statements are on canvas or within a galley context, they challenge the most sacred theories of modern art, what the artist calls “received wisdom.”

Baldessari’s word paintings of the late 1960s and early 1970s are a case in point. Many were hand-lettered onto stretched canvas by sign painters that Baldessari had hired to render statements that that he had not even written but had only read. These are often statements that naively set out define the most elusive of questions that confront artists. And they are rendered in the clearest most direct lettering possible, the lettering found on a sign, the most earnest typography that directs and informs in the most straightforward manner possible. We cannot help but trust what these sign paintings tell us, even when Baldessari’s word paintings offer audaciously innocent solutions to the complex theory-soaked issues that define modernism.

Works of art such as What is Painting, 1966-68, Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work, 1966-68 and Composing on a Canvas, 1966-68 are brilliantly ambitious. They layer the false objectivity of didactic grammar and clear careful hand lettering over impossibly trite yet seductive solutions at the very core of art’s definition.

For example, What is Painting tries to define what painting is and does so in only three short sentences. But these sentences are written on a canvas and so inherit a fraught five hundred year history of art making. What makes these issues all the more pleasantly absurd is that Baldessari is at least as well known for his long career as a teacher as he is as an artist. So when he offers paintings with statements such as, “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work,” the allegedly instructive nature is given more weight and is ultimately more absurd.

Nova Scotia College of Art and Design

Soon after the Cremation Project, Baldessari was asked by the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design to exhibit his work there. Instead of sending art, Baldessari sent instructions to the school in the form of a letter for the initial iteration of I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, a work based on a sentence Baldessari had written to himself in a notebook he then kept. The letter reads in part,

…I have no idea what your gallery looks like of course, and I know that you do not have much money for shows so that conditions my ideas of course….I’ve got a punishment piece. It will require a surrogate or surrogates since I cannot be there to… impose punishment. But that’s ok, since the theory is that punishment should be instructive for others. And there is a precedent for it, Christ being punished for our sins, and many others. So some student scapegoats are necessary. If you can’t induce anybody to be sacrificial and take my sins upon their shoulders, then use whatever funds there are, fifty dollars, to pay someone as a mercenary.

The piece is this, from floor to ceiling should be written by one or more people, one sentence under another, the following statement: I will not make any more bad art.

At least one column of the sentence should be done floor to ceiling before the exhibit opens and the writing of the sentence should continue everyday, if possible, for the length of the exhibit. I would appreciate it if you could tell me how many times the sentence has been written after the exhibit closes. It should be hand written, clearly written with correct spelling….2

By the end of the exhibit the walls were covered with Baldessari’s statement of sacrificial punishment and he allowed the school to create a lithograph of the work for their fundraising based on his own handwriting.

A Strategist

Baldessari has called himself “purely a strategist” and in I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art he references the fundamental modernist tension between the word and image that Magritte had exposed in The Treachery of Images and the cool, spare, self-referential repetitions of the minimalists. John Baldessari has spent his career coaxing beauty and complexity from our prosaic visual culture.

Special thanks to Sandy Heller, The Heller Group, LLC

1. Excerpt from, John Baldessari, Cremation Piece, 1969 in Donald Kuspit, “Semiotic Anti-Subject,” Artnet, originally from three Getty lectures delivered at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Southern California, April 4, 6 and 10, 2000.

2. Excerpt transcribed from video, “Curator Chrissie Iles on John Baldessari’s I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art,” Whitney Museum of American Art, December 2010.

Additional Resources:

Whitney Museum recreation of I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art

Hans Haacke, Seurat’s “Les Poseuses” (small version), 1884-1975

by SAL KHAN, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Hans Haacke, Seurat’s “Les Poseuses” (small version), 1884-1975, 1975

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii

by TINA RIVERS RYAN

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Getting on the “Electronic Super Highway”

In 1974, artist Nam June Paik submitted a report to the Art Program of the Rockefeller Foundation, one of the first organizations to support artists working with new media, including television and video. Entitled “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Society—The 21st Century is now only 26 years away,” the report argued that media technologies would become increasingly prevalent in American society, and should be used to address pressing social problems, such as racial segregation, the modernization of the economy, and environmental pollution. Presciently, Paik’s report forecasted the emergence of what he called a “broadband communication network”—or “electronic super highway”—comprising not only television and video, but also “audio cassettes, telex, data pooling, continental satellites, micro-fiches, private microwaves and eventually, fiber optics on laser frequencies.” By the 1990s, Paik’s concept of an information “superhighway” had become associated with a new “world wide web” of electronic communication then emerging—just as he had predicted.

From Music to Fluxus

Paik was well-positioned to understand how media technologies were evolving: in the 1960s he was one of the very first people to use televisual technologies as an artistic medium, earning him the title of “father” of video art. Born in Seoul in 1932, Paik studied composition while attending college in Tokyo; he eventually travelled to Germany, where he hoped to encounter the leading composers of the day. He met John Cage in 1958, and soon became involved with the avant-garde Fluxus group, led by Cage’s student George Maciunas. Explain Fluxus.

Following the example of Cage’s oeuvre, many of Paik’s Fluxus works undermined accepted notions of musical composition or performance. This same irreverent spirit informed his use of television, to which he turned his attention in 1963 in his first one-man gallery show, “Exposition of Music—Electronic Television,” at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany. Here, Paik became the first artist to exhibit what would later become known as “video art” by scattering television sets across the floor of a room, thereby shifting our attention from the content on the screens to the sculptural forms of the sets.

The father of video art

Paik moved to New York in 1964, where he came into contact with the downtown art scene. In 1965, he began collaborating with cellist Charlotte Moorman, who would wear and perform Paik’s TV sculptures for many years; he also had a one-man show at the 57th Street Galeria Bonino, in which he exhibited modified or “prepared” television sets that upset the traditional TV-watching experience. One example is Magnet TV, in which an industrial magnet is placed on top of the TV set, distorting the broadcast image into abstract patterns of light.

According to an oft-cited story, on October 4th of that same year, Paik purchased the first commercially-available portable video system in America, the Sony Portapak, and immediately used it to record the arrival of Pope Paul VI at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Later that night, Paik showed the tape at the Café au Go Go in Greenwich Village, ushering in a new mode of video art based not on the subversion or distortion of television broadcasts, but on the possibilities of videotape. The evolution of these tendencies into a new movement was announced by a 1969 group show, “TV as a Creative Medium.” Held at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York, the show included one of Paik’s interactive TVs, and also premiered another one of his collaborations with Moorman.

TV as a Creative Medium

For Paik and other early adopters of video, this new artistic medium was well-suited to the speed of our increasingly electronic modern lives. It allowed artists to create moving images more quickly than recording on film (which required time for negatives to be developed), and unlike film, video could be edited in “real-time,” using devices that altered the video’s electronic signals. (Ever the pioneer, Paik created his own video synthesizer with engineer Shuya Abe in 1969.) Furthermore, because the image recorded by the video camera could be transmitted to and viewed almost instantaneously on a monitor, people could see themselves “live” on a TV screen, and even interact with their own TV image, in a process known as “feedback.” In the years to come, the participatory nature of TV would be redefined by two-way cable networks, while the advent of global satellite broadcasts made TV a medium of instant global communication.

As television continued to evolve from the late 1960s onward, Paik explored ways to disrupt it from both inside and outside of the institutional frameworks of galleries, museums, and emerging experimental TV labs. His major works from this period include TV Garden (1974), a sculptural installation of TV sets scattered among live plants in a museum (image above), and Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984), a broadcast program that coordinated live feeds from around the world via satellite. In these and other projects, Paik’s goal was to reflect upon how we interact with technology, and to imagine new ways of doing so. The many retrospectives of his work in recent decades, including one organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2012, speak to the increasing relevance of his ideas for contemporary art.

The nation electric

By the 1980s, Paik was building enormous, free-standing structures comprising dozens or even hundreds of TV screens, often organized into iconic shapes, as in the giant pyramid of V-yramid (1982). For the German Pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale, Paik produced a series of works about the relationship between Eastern and Western cultures, framed through the lens of Marco Polo; along with Hans Haacke, another artist representing Germany, Paik was awarded the prestigious Golden Lion. One of the works, Electronic Superhighway, was a towering bank of TVs that simultaneously screened multiple video clips (including one of John Cage) from a wide variety of sources. Two years later, Paik revisited this work in Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, placing over 300 TV screens into the overall formation of a map of the United States outlined in colored neon lights (see image at the top of the page and the detail below). Roughly forty feet long and fifteen feet high, the work is a monumental record of the physical and also cultural contours of America: within each state, the screens display video clips that resonate with that state’s unique popular mythology. For example, Iowa (where each presidential election cycle begins) plays old news footage of various candidates, while Kansas presents the Wizard of Oz.

The states are firmly defined, but also linked, by the network of neon lights, which echoes the network of interstate “superhighways” that economically and culturally unified the continental U.S. in the 1950s. However, whereas the highways facilitated the transportation of people and goods from coast to coast, the neon lights suggest that what unifies us now is not so much transportation, but electronic communication. Thanks to the screens of televisions and of the home computers that became popular in the 1990s, as well as the cables of the internet (which transmit information as light), most of us can access the same information at anytime and from any place. Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, which has been housed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum since 2002, has therefore become an icon of America in the information age.

While Paik’s work is generally described as celebrating the fact that the “electronic superhighway” allows us to communicate with and understand each other across traditional boundaries, this particular work also can be read as posing some difficult questions about how that technology is impacting culture. For example, the physical scale of the work and number of simultaneous clips makes it difficult to absorb any details, resulting in what we now call “information overload,” and the visual tension between the static brightness of the neons and the dynamic brightness of the screens points to a similar tension between national and local frames of reference.

Additional resources:

Nam June Paik, bio and collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Nam June Paik, TV Garden at the Guggenheim

Nam June Paik from the National Endowment for the Arts

Nam June Paik archive at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Nam June Paik from the Asia Society

Electronic Superhighway – American Experience in the Classroom (The Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Melissa Chiu and Michelle Yun, eds., Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot (New York: Asia Society Museum, 2014).

John G. Hanhardt and Ken Hakuta, Nam June Paik: Global Visionary (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2012).

John G. Hanhardt and Jon Ippolito, The Worlds of Nam June Paik (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2000).

Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama, Narcissus Garden

Narcissism

Today there are few female artists who are more visible to a wide range of international audiences than Yayoi Kusama, who was born in 1929 in Japan. Kusama is a self-taught artist who now chooses to live in a private Tokyo mental health facility, while prolifically producing art in various media in her studio nearby. Her highly constructed persona and self-proclaimed life-long history of insanity have been the subject of scrutiny and critiques for decades. Art historian Jody Cutler places Kusama’s oeuvre “in dialogue with the psychological state known as narcissism,” as “narcissism is both the subject and the cause of Kusama’s art, or in other words, a conscious artistic element related to content.”[1] It is within this context that we examine Kusama and her infamous Narcissus Garden (narcissism is, in part, the egotistic admiration of one’s self).

Mirrors

Kusama arrived in New York City from Japan in 1958 and immediately approached dealers and artists alike to promote her work. Within the first few years she began to exhibit and associate herself with seminal artists and critics, such as Donald Judd, Joseph Cornell, Yves Klein, and Lucio Fontana who later was instrumental in her realizing Narcissus Garden.

In 1965, she mounted her first mirror installation Infinity Mirror Room-Phalli’s Field at Castellane Gallery in New York (left). A mirrored room without a ceiling was filled with colorfully dotted, phallus-like stuffed objects on the floor. The repeated reflections in the mirrors conveyed the illusion of a continuous sea of multiplied phalli expanding to its infinity. This playful and erotic exhibition immediately attracted the media’s attention.

Narcissus Garden, 1966

The pinnacle of her succès de scandale culminated in the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. Although Kusama was not officially invited to exhibit, according to her autobiography, she received the moral and financial support from Lucio Fontana and permission from the chairman of the Biennale Committee to stage 1,500 mass-produced plastic silver globes on the lawn outside the Italian Pavilion. The tightly arranged 1,500 shimmering balls constructed an infinite reflective field in which the images of the artist, the visitors, the architecture, and the landscape were repeated, distorted, and projected by the convex mirror surfaces that produced virtual images appearing closer and smaller than reality. The size of each sphere was similar to that of a fortune-teller’s crystal ball. When gazing into it, the viewer only saw his/her own reflection staring back, forcing a confrontation with one’s own vanity and ego.

During the opening week, Kusama placed two signs at the installation: “NARCISSUS GARDEN, KUSAMA” and “YOUR NARCISSIUM [sic] FOR SALE” on the lawn. Acting like a street peddler, she was selling the mirror balls to passers-by for two dollars each, while distributing flyers with Herbert Read’s complimentary remarks about her work on them. She consciously drew attention to the “otherness” of her exotic heritage by wearing a gold kimono with a silver sash. The monetary exchange between Kusama and her customers underscored the economic system embedded in art production, exhibition and circulation. The Biennale officials eventually stepped in and put an end to her “peddling.” But the installation remained.[2] Her interactive performance and eye-catching installation garnered international press coverage. This original installation of Narcissus Garden from 1966 has been frequently interpreted by many as both Kusama’s self-promotion and her protest of the commercialization of art. [3]

The life of Narcissus Garden after 1966

Since then, Kusama’s oeuvre has become integrated into the canon of art history, and popular with art institutions around the world. In 1993, Kusama was officially invited to represent Japan at the 45th Venice Biennale.

Her Narcissus Garden continues to live on. It has been commissioned and re-installed at various settings, including the Brazilian business tycoon Bernardo de Mello Paz’s Instituto Inhotim (left), Central Park in New York City, as well as retail booths at art fairs.

The re-creation of Narcissus Garden has erased the notion of political cynicism and social critique; instead, those shiny balls, now made of stainless steel and carrying hefty price tags, have become a trophy of prestige and self-importance. Originally intended as the media for an interactive performance between the artist and the viewer, the objects are now regarded as valuable commodities for display.

The profound narcissistic undertone however has been ironically amplified not only by the artist’s pervasive ostentation, but also by the viewership in the age of Internet. Seduced by his/her own reflective images on the convex surfaces, viewers snap photographs with a smart phone and instantly upload them to social media for the rest of the world to see. The urge to capture and disseminate the moment one’s own image coalesces onto a privileged object in a privileged institution seems to motivate the obsession with the self. To further accentuate the effect of gazing at one’s multiple selves, many installations now take place on the water where the original Narcissus from the Greek mythology fell in love with his own reflection and eventually drowned.

[1] Jody Cutler. 2011. “Narcissus, Narcosis, Neurosis: The Visions of Yayoi Kusama,” in Contemporary Art and Classical Myth, edited by Isabelle Loring Wallace, Jennie Hirsh, (London: Ashgate Publishing ltd), p. 89.

[2] There are a few discrepancies in the anecdote of this event between Kusama’s autobiography and art historians and critics. For example, 1) Kusama claims that the installation was not exactly a guerrilla act, because she received permission from the Biennale official, though she did not have an official invitation as a Biennale participant; 2) according to Kusama, the installation itself was NOT removed after she was asked to stop selling the balls; and 3) in her autobiography, the balls were made of plastic in 1966 not stainless steel.

[3] It is worth noting that the following Venice Biennale, in 1968, was marked by social and economic turmoil around the globe, and was struck by the student movement in Italy and a boycott by international artists. The Biennale was labeled as a fascist, capitalist, and commercial. In contrast to Kusama’s action, many artists who were officially invited to participate decided to close exhibition halls, withdraw their works, and join street demonstrations resulting in the closure of the Biennale sales office and the end of Biennale prizes until 1986.

Additional resources:

Kusama and Experimentation (Tate blog)

Kusama and Self-obliteration (Tate blog)

TateShots: Kusama’s Obliteration Room

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, translated by Ralph McCarthy (London: Tate Enterprises Ltd., 2013) (see the section, “On an endless Highway”).

Yayoi Kusama (Tate)

by TATE

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): The nine decades of Yayoi Kusama’s (草間彌生) life have taken her from rural Japan to the New York art scene to contemporary Tokyo, in a career in which she has continuously innovated and re-invented her style. Video from Tate

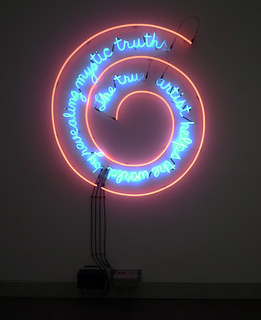

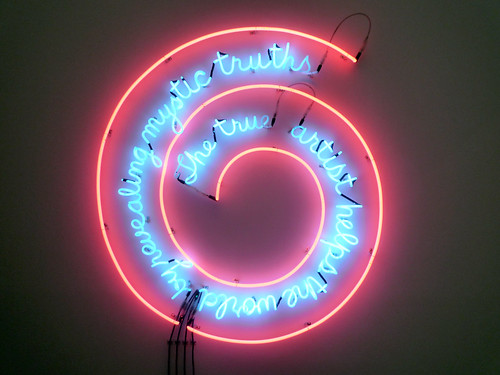

Bruce Nauman, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths

by JP MCMAHON

Bruce Nauman’s neon sign asks a multitude of questions with regard to the ways in which the 20th century conceived both avant-garde art and the role of the artist in society. If earlier European modernists, such as Mondrian, Malevich, and Kandinsky, sought to use art to reveal deep-seated truths about the human condition and the role of the artist in general, then Bruce Nauman’s The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths questions such transhistorical and universal statements. With regard to this work, Nauman said:

The most difficult thing about the whole piece for me was the statement. It was a kind of test—like when you say something out loud to see if you believe it. Once written down, I could see that the statement […] was on the one hand a totally silly idea and yet, on the other hand, I believed it. It’s true and not true at the same time. It depends on how you interpret it and how seriously you take yourself. For me it’s still a very strong thought.

The medium and the message

By using the mediums of mass culture (neon signs) and of display (he originally hung the sign in his storefront studio), Nauman sought to bring questions normally considered only by the high culture elite, such as the role and function of art and the artist in society, to a wider audience. While early European modernists, such as Picasso, had borrowed widely from popular culture, they rarely displayed their work in the sites of popular culture. For Nauman, both the medium and the message were equally important; thus, by using a form of communication readily understood by all (neon signs had been widespread in modern industrial society) and by placing this message in the public view, Nauman let everyone ask and answer the question.

While it is perhaps the words that stand out most, the symbolism of the spiral (think of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, 1969), also deserves attention having been used for centuries in European and other civilizations, such as megalithic and Chinese art, both as a symbol of time and of nature itself.

Transcendence?

Theosophy is interesting in this regard and was an important aspect of the early European Avant-garde. In particular, Theosophists believed that all religions are attempts to help humanity to evolve to greater perfection, and that each religion therefore holds a portion of the truth. Through their materials, artists had sought to transform the physical into the spiritual. In this sense, Malevich, Mondrian, and Kandinsky sought to use the material of their art to transcend it: Nauman, and other of his generation, did not.

Process over product

Instead, Nauman’s work transgresses many genres of art making in that his work explores the implications of minimalism, conceptual, performance, and process art. In this sense we could call Nauman’s art “Postminimalism,” a term coined by the art critic Robert Pincus-Witten, in his article “Eva Hesse: Post-Minimalism into Sublime” (Artforum 10, number 3, November 1971). Artists such as Nauman, Acconci, and Hesse, favored process instead of product, or rather the investigation over the end result. However, this is not to say they did not produce objects, such as the neon-sign by Nauman, only that within the presentation of the object, they also retained an examination of the processes that made that specific object.

In this sense, Nauman’s neon sign isn’t only an object, it’s a process, something that continues to make us think about art, artist, and the role that language plays in our conception of both. The words continue to ask this of each beholder who encounters them. Does the artist, the “true artist” really “reveal mystical truths”? Or confined to the specific culture that it was made in? If we are to believe the statement (remember, it is not necessarily Nauman’s, he merely borrows it from our shared culture), then we might, for example, recognize Leonardo da Vinci as a Neo-Platonic artist who showed us ultimate and essential truths through painting. On the other hand, if we reject the statement, then we would probably recognize the artist as just another producer of a specific set of objects, that we call “art.”

This type of logic and analytical thinking was influenced by Nauman’s reading of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (1953). From Wittgenstein, Nauman took the idea that you put forth a proposition/idea in the form of language and then examine its findings, irrespective of its proof or conclusion. Nauman’s “language games,” his neon-words, his proposition about the nature of art and the artist continue to resonant in today’s art world, in particular with regard to the value we place on the artist’s actions and findings.

Additional resources:

This work of art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Art:21 page about Nauman’s The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truth

Performance art

Performance art differs from traditional theater in its rejection of a clear narrative, use of random or chance-based structures, and direct appeal to the audience.

c. 1960 - present

Performance Art: An Introduction

When Art Intersects With Life

Many people associate performance art with highly publicized controversies over government funding of the arts, censorship, and standards of public decency. Indeed, at its worst, performance art can seem gratuitous, boring or just plain weird. But, at its best, it taps into our most basic shared instincts: our physical and psychological needs for food, shelter, sex, and human interaction; our individual fears and self-consciousness; our concerns about life, the future, and the world we live in. It often forces us to think about issues in a way that can be disturbing and uncomfortable, but it can also make us laugh by calling attention to the absurdities in life and the idiosyncrasies of human behavior.

Performance art differs from traditional theater in its rejection of a clear narrative, use of random or chance-based structures, and direct appeal to the audience. The art historian RoseLee Goldberg writes:

Historically, performance art has been a medium that challenges and violates borders between disciplines and genders, between private and public, and between everyday life and art, and that follows no rules.*

Although the term encompasses a broad range of artistic practices that involve bodily experience and live action, its radical connotations derive from this challenge to conventional social mores and artistic values of the past.

Historical Sources

While performance art is a relatively new area of art history, it has roots in experimental art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Echoing utopian ideas of the period’s avant-garde, these earliest examples found influences in theatrical and music performance, art, poetry, burlesque and other popular entertainment. Modern artists used live events to promote extremist beliefs, often through deliberate provocation and attempts to offend bourgeois tastes or expectations. In Italy, the anarchist group of Futurist artists insulted and hurled profanity at their middle-class audiences in hopes of inciting political action.

Following World War II, performance emerged as a useful way for artists to explore philosophical and psychological questions about human existence. For this generation, who had witnessed destruction caused by the Holocaust and atomic bomb, the body offered a powerful medium to communicate shared physical and emotional experience. Whereas painting and sculpture relied on expressive form and content to convey meaning, performance art forced viewers to engage with a real person who could feel cold and hunger, fear and pain, excitement and embarrassment—just like them.

Action & Contingency

Some artists, inspired largely by Abstract Expressionism, used performance to emphasize the body’s role in artistic production. Working before a live audience, Kazuo Shiraga of the Japanese Gutai Group made sculpture by crawling through a pile of mud. Georges Mathieu staged similar performances in Paris where he violently threw paint at his canvas. These performative approaches to making art built on philosophical interpretations of Abstract Expressionism, which held the gestural markings of action painters as visible evidence of the artist’s own existence. Bolstered by Hans Namuth’s photographs of Jackson Pollock in his studio, moving dance-like around a canvas on the floor, artists like Shiraga and Mathieu began to see the artist’s creative act as equally important, if not more so, to the artwork produced. In this light, Pollock’s distinctive drips, spills and splatters appeared as a mere remnant, a visible trace left over from the moment of creation.

Shifting attention from the art object to the artist’s action further suggested that art existed in real space and real time. In New York, visual artists combined their interest in action painting with ideas of the avant-garde composer John Cage to blur the line between art and life. Cage employed chance procedures to create musical compositions such as 4’33”. In this (in)famous piece, Cage used the time frame specified in the title to bracket ambient noises that occurred randomly during the performance. By effectively calling attention to the hum of fluorescent lights, people moving in their seats, coughs, whispers, and other ordinary sounds, Cage transformed them into a unique musical composition.

The Private Made Political

Drawing on these influences, new artistic formats emerged in the late 1950s. Environments and Happenings physically placed viewers in commonplace surroundings, often forcing them to participate in a series of loosely structured actions. Fluxus artists, poets, and musicians likewise challenged viewers by presenting the most mundane events—brushing teeth, making a salad, exiting the theater—as forms of art. A well-known example is the “bed-in” that Fluxus artist Yoko Ono staged in 1969 in Amsterdam with her husband John Lennon. Typical of much performance art, Ono and Lennon made ordinary human activity a public spectacle, which demanded personal interaction and raised popular awareness of their pacifist beliefs.

In the politicized environment of the 1960s, many artists employed performance to address emerging social concerns. For feminist artists in particular, using their body in live performance proved effective in challenging historical representations of women, made mostly by male artists for male patrons. In keeping with past tradition, artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke and Valie Export displayed their nude bodies for the viewer’s gaze; but, they resisted the idealized notion of women as passive objects of beauty and desire. Through their words and actions, they confronted their audiences and raised issues about the relationship of female experience to cultural beliefs and institutions, physical appearance, and bodily functions including menstruation and childbearing. Their ground-breaking work paved the way for male and female artists in the 1980s and 1990s, who similarly used body and performance art to explore issues of gender, race and sexual identity.

Where Is It?

Throughout the mid-twentieth century, performance has been closely tied to the search for alternatives to established art forms, which many artists felt had become fetishized as objects of economic and cultural value. Because performance art emphasized the artist’s action and the viewer’s experience in real space and time, it rarely yielded a final object to be sold, collected, or exhibited. Artists of the 1960 and 70s also experimented with other “dematerialized” formats including Earthworks and Conceptual Art that resisted commodification and traditional modes of museum display. The simultaneous rise of photography and video, however, offered artists a viable way to document and widely distribute this new work.

Performance art’s acceptance into the mainstream over the past 30 years has led to new trends in its practice and understanding. Ironically, the need to position performance within art’s history has led museums and scholars to focus heavily on photographs and videos that were intended only as documents of live events. In this context, such archival materials assume the art status of the original performance. This practice runs counter to the goal of many artists, who first turned to performance as an alternative to object-based forms of art. Alternatively, some artists and institutions now stage re-enactments of earlier performances in order to recapture the experience of a live event. In a 2010 retrospective exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, for example, performers in the galleries staged live reenactments of works by the pioneering performance artist Marina Abramovic, alongside photographs and video documentation of the original performances.

Don’t Try This At Home

New strategies, variously described as situations, relational aesthetics, and interventionist art, have recently begun to appear. Interested in the social role of the artist, Rirkrit Tiravanija stages performances that encourage interpersonal exchange and shared conversation among individuals who might not otherwise meet. His performances have included cooking traditional Thai dinners in museums for viewers to share, and relocating the entire contents of a gallery’s offices and storage rooms, including the director at his desk, into public areas used to exhibit art. Similar to performance art of the past, such approaches engage the viewer and encourage their active participation in artistic production; however, they also speak to a cultural shift toward interactive modes of communication and social exchange that characterize the 21st century.

* RoseLee Goldberg. Performance: Live art since the 60s, New York: Thames & Hudson, 1998, page 20.

Additional resources:

Video of John Cage’s 4″33″ performed by the BBC Symphoney Orchestra at the Barbican Centre in 2004

The Case for Performance Art

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Speaker: Sarah Urist Green

Vito Acconci, Following Piece

by JP MCMAHON

Conceived by performance and conceptual artist Vito Acconci, Following Piece was an activity that took place everyday on the streets of New York, between October 3rd and 25th, 1969. It was part of other performance and conceptual events sponsored by the Architectural League of New York that occurred during those three weeks. The terms of the exhibition “Street Works IV” were to do a piece, sometime during the month, that used a street in New York City. So Acconci decided to follow people around the streets and document his following of them. But why would he do this? Why would Acconci follow random people around New York?

Acconci’s work is typical of performance and conceptual art made during this period in the way that he uses his body as the object of his art in order to explore some specific idea. In essence, Following Piece was concerned with the language of our bodies, not so much in a private manner, but in a deeply public manner. By selecting a passer-by at random until they entered a private space, Acconci submitted his own movements to the movements of others, showing how our bodies are themselves always subject to external forces that we may or may not be able to control. In his notes that the artist kept during the performance, Acconci wrote:

Following Piece, potentially, could use all the time allotted and all the space available: I might be following people, all day long, everyday, through all the streets in New York City. In actuality, following episodes ranged from two or three minutes when someone got into a car and I couldn’t grab a taxi, I couldn’t follow – to seven or eight hours – when a person went to a restaurant, a movie.

In terms of the art work, rather than being just another object that we look at in the gallery, Following Piece was part of the revolution that took place in the art world in the late 1960s that tried to bring art out of the gallery and into the street in order to explore real issues such as space, time, and the human body. Many artists, such as Acconci, used their bodies as their chosen medium. Look at some of Acconci’s notes of the period which he wrote before, during and after the event:

- I need a scheme (follow the scheme, follow a person)

- I add myself to another person (I give up control/I don’t have to control myself)

- Subjective relationship; subjunctive relationship

- A way to get around. (A way to get myself out of the house.) Get into the middle of things.

- Out of space. Out of time. (My time and space are taken up, out of myself, into a larger system).

All of these ideas were influenced by Acconci’s readings. As many other artists of the period, Acconci wanted to get away from specific art problems and engage with social problems. Acconci read books such as Edward Hall’s The Hidden Dimension (1969), Erving Goffmann’s The Presentation of the Self in Every Day Life (1959), and Kurt Lewin’s In Principles of Topological Psychological (1936/1966). All of these books explored the ways in which the individual and the social are interlinked in terms of complex codes that structure the way we act and live everyday.

With regard to the influence on these texts on Following Piece, Acconci’s use of diagrams specifically refers to Lewin’s notion of “field theory”: that is, a model that sought to explain human behaviour in terms of relations and in relation to its environment and surroundings. Lewin placed behaviour in a “field” in order to examine it in a theoretical manner. The diagrams drawn by Acconci are an imaginative engagement with this idea of human relations as engaging in a specific field or space. So by following someone around New York, Acconci could perhaps experience what it was like to relinquish self control to others and also explore the intersecting systems that grouped different people together in one field. As we can see from the diagrams, Acconci’s intentions were not subjective but much more systematic—they constituted an exploration of the private and public fields that occur in every social space.

Ironically, for all the effort to get out of the gallery, much of Acconci’s documentation of Following Piece, for example, the texts, photographs (which were taken after the event!), and diagrams, now constitutes a work of art in its own right. MoMA owns several of the photographs of Following Piece and other “versions” of this work are also in existence. So, even though Acconci’s Following Piece was a performance that occurred in a very specific period (3rd to 25th October, 1969), the reproduction and circulation of the work continues. This fact not only teaches us important things about the nature of performance art and its relationship to the art world, but also how the context of the art work is also never exactly fixed and each time it is presented something new occurs with the work itself.

Additional Resources:

Following Piece photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Willoughby Sharp video interview with Vito Acconci (1973) includes discussion of Following Piece

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside (July 23, 1973)

by PATRICIA HICKSON, WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside (July 23, 1973), Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art ©Mierle Laderman Ukeles

Additional Resources:

This work at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Jillian Steinhauer “How Mierle Laderman Ukeles Turned Maintenance Work into Art” Hyperallergic

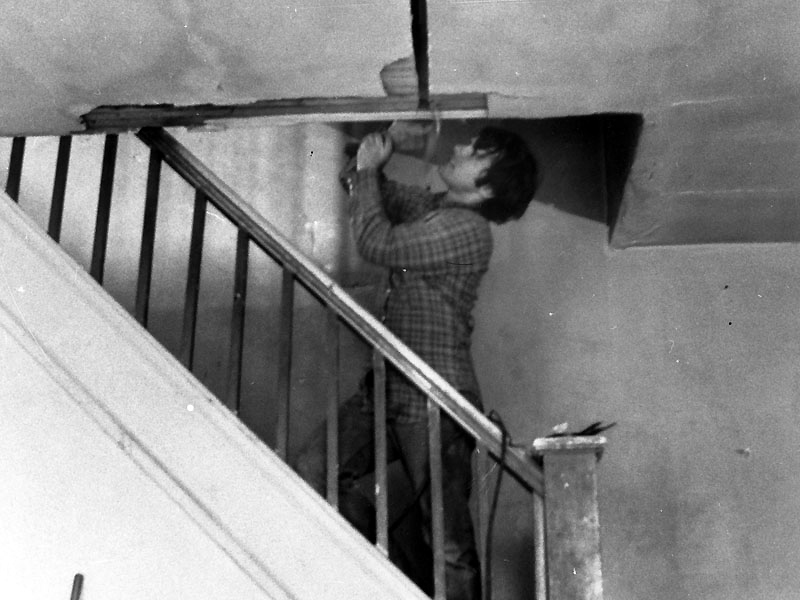

Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting

Rather surprising things

“Over the past ten years,” the American art historian and critic Rosalind Krauss wrote in 1979, “rather surprising things have come to be called sculpture: narrow corridors with TV monitors at the ends; large photographs documenting country hikes; mirrors placed at strange angles in ordinary rooms; temporary lines cut into the floor of the desert.” [1] To this list, we could add Gordan Matta-Clark’s Splitting, 1974, in which a suburban home in Englewood, New Jersey slated for demolition was sliced nearly in half.

Matta-Clark had taken a chainsaw to make two parallel, vertical cuts beginning at the roof’s center; the house was nearly cleaved in half, each half shifted outwards leaving a long narrow “V” shape allowing light to filter inside. It was a laborious process that involved the assistance of several friends and the resulting structure, demolished some three months later as part of an urban renewal project, was documented in photographs.

Splitting also served as the site for at least one “field trip” — the art dealer Holly Solomon (who had purportedly purchased the house as an investment), several artists, and gallery goers boarded a bus from downtown Manhattan to visit the house (a 16 mm film, now in the collection of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, documented the trip).

Post-medium

Beginning in the 1970s, contemporary art abandoned the traditional forms it had historically taken. Painting and sculpture became almost unrecognizable as such. Krauss would later characterize it as a “post-medium” condition, a condition, in other words, in which the familiar categories that defined Western art for centuries were overturned. The medium, that which constituted the material or form of a given artwork, became obsolete, or at least radically reformulated: an art work could now exist in any form.

If Gordan Matta-Clark could be said to be associated with any one particular medium, it would be architecture. The entirety of his work, of which Splitting stands as exemplary, consisted of alterations to the architecture of abandoned or condemned buildings. In his other work, sections of floors and walls were removed, and sometimes those removed sections themselves become the artwork; in other cases it was the void formed from the removal that is the focus.

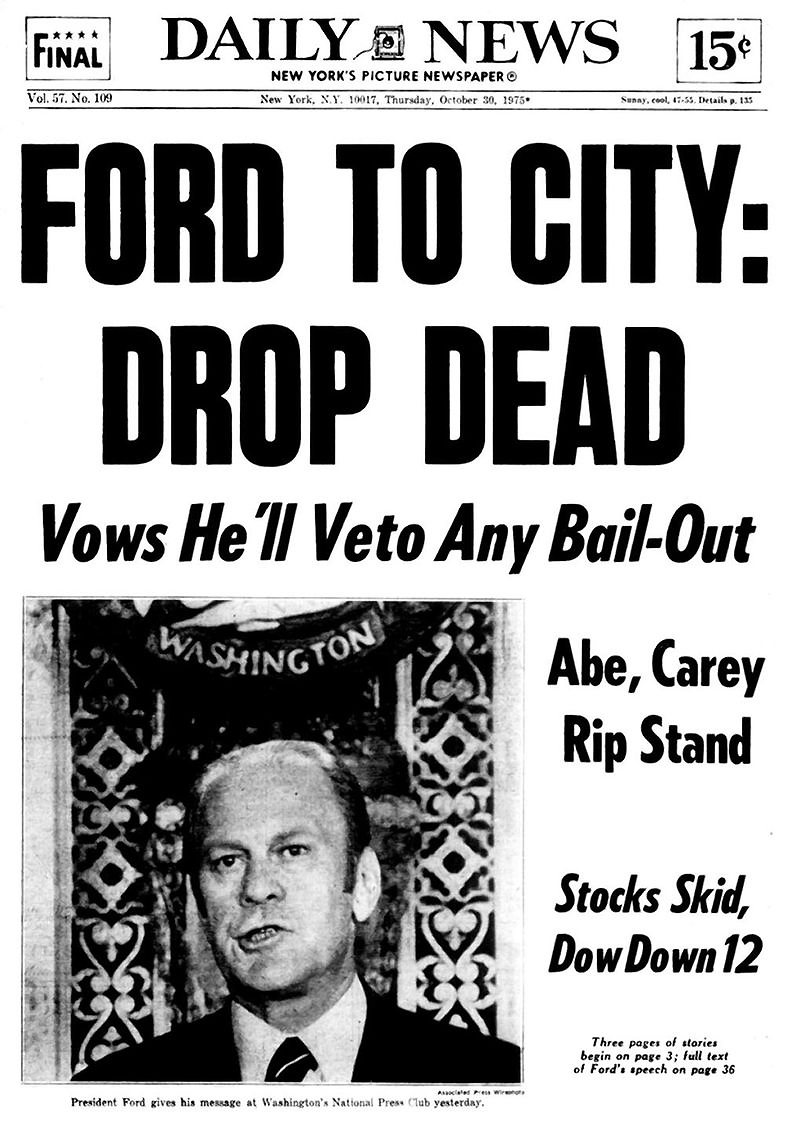

Matta-Clark began his interventions into the urban environment at a time when New York, where the artist lived and worked, was a city in crisis as a result of economic downturns. President Gerald Ford gave a speech denying federal assistance that would have rescued New York from what seemed like certain bankruptcy in the same year the artist made Splitting. The Daily News reported on its front page the very next day: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

Matta-Clark had seen his own neighborhood in lower Manhattan negatively impacted by modernization ever since the influential city planner Robert Moses attempted to push a freeway through Washington Square Park in the 1950s. Trained as an architect, Matta-Clark likely saw through the glossy rhetoric of urban renewal projects — though they promised regeneration such plans destroyed existing neighborhoods.

Anarchitecture

In March 1974, Matta-Clark joined a collective of artists who mounted an exhibition entitled Anarchitecture at 112 Greene Street in New York City. The premise was embodied in the title which merged the term “anarchy” with “architecture;” the artists in the collective were all interested in exploring new ideas of form and space in the midst of urban decay. One year later, and out of his experience working with this community of like-minded artists, came Splitting. But Matta-Clark’s destroyed house was not just giving visual shape to the crisis of a neighborhood or even of a city on the verge of collapse, dire as those conditions surely were.

Modernism formed the larger horizon of Splitting’s meaning; its philosophy of the new and of progress that had underwritten the utopianism of over 100 years of art and architecture was suddenly untenable. New York City had long defined industrial modernity — its soaring skyscrapers of the early twentieth century were second only to Chicago’s equally impressive skyline — and its seeming collapse was yet another symbol of a crisis of modernity. No wonder many people came to speak of postmodernity. In architecture particularly there was already a sense that the great utopian project of modernism had failed.

It has become almost obligatory to describe Matta-Clark’s work as a critique of modernist architecture — and more generally modernist art — an intervention, interrogation, disruption, investigation (all words you will encounter in the study of any postmodern or contemporary art work). But as much as Splitting may be regarded as critical commentary on the idea of progress and a work that helps to lay the groundwork for a postmodern aesthetic (in which artists were seen to be social commentators, engaged participants in the larger realm of visual culture, or even political activism), another aspect of the artist’s work bears consideration.

There is a melancholy and nostalgia that pervades Matta-Clark’s fragments of walls, floors, cut-through spaces or domestic interiors opened to the outside. Much like the fascination with the ruins of antiquity that peppered the landscape of Europe during the eighteenth century when classical antiquity was discovered anew, Matta-Clark’ s works speak in poignant tones of the demise of the modern as both an aesthetic ideal and a utopia.

Notes:

[1] Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,”October Vol. 8 (Spring, 1979), p. 30.

References:

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,”October Vol. 8 (Spring, 1979), p. 30 – 44.

Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Additional Resources:

The Canadian Centre for Architecture’s Gordon Matta-Clark Collection.

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present

Transcendence

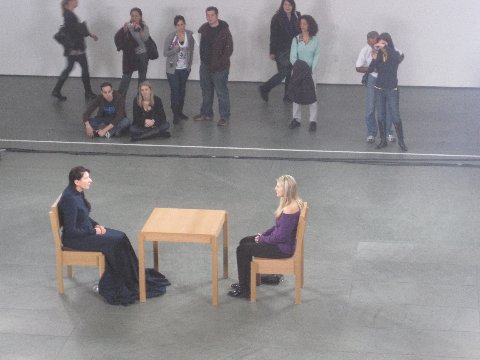

“Sit silently with the artist for a duration of your choosing”—so the instructions read on a small plaque in the second-floor atrium at The Museum of Modern Art. Behind the plaque, a queue of visitors forms, eager to enter a large square space—demarcated only by tape on the floor—to sit down at a wooden table across from a dark-haired woman in a navy-blue dress that conceals every part of her body save her face and her hands.

The woman is the pioneering artist Marina Abramović, but its likely that few of the people in line have any sense of this woman’s indelible impact on contemporary art. As I wait, an anthology of her performances scrolling through my head. Watching her from afar, I look to see the courage and fearlessness in a woman capable of incising a five-pointed star on her own stomach, screaming until she loses consciousness, and living in a gallery for 12 days without food. Strangely, she doesn’t seem reckless at all, but peaceful and wise. I then remember she trained with Tibetan Buddhists and has said she’s able to transcend the limits of her own body and mind through meditation. She’ll need these skills now more than ever as she attempts her longest performance-to-date, sitting at this table for every hour of every day that her retrospective is open at MoMA. No food. No water. No breaks.

My turn

So, I wait for my moment with the artist, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. A young girl is sitting across from Marina and the two seem engaged in a staring contest, though from that distance it’s impossible to tell if they’re actually making eye contact or simply staring ahead in a daze. Seventy-five minutes later she finally stands up and exits the square, declaring she lost all sense of time and thought it had only been a few minutes. Marina leans forward and closes her eyes, while the next sojourner steps forward and takes the empty seat. Marina sits up and another staring contest commences—this one lasting sixty-seven minutes. This process repeats—ten minutes, fifty-five minutes, twenty minutes, forty-five minutes, etc. Finally, the man in front of me takes the seat and I’m next. More than three hours from when I entered the succession I’ve seen only six people participate in the performance and more than thirty leave the line in frustration. The nameless, faceless strangers I queued with hours ago are now friends—an artist from Poughkeepsie, an art history undergrad from Chicago, a nurse from outside Philly—and we share our excitement as our turn approaches. Finally, after nearly four hours, my time has come.

I enter the square and approach the table, immediately noting the heat of the lights and the watchful eyes of the crowds gathered to gawk at the spectacle. I put my purse on the floor and take a seat. While Marina leans forward, I settle into the chair and imagine I’ll last about ten minutes before I become either bored or totally uncomfortable. She begins to sit up and I try to prepare myself for the moment she opens her eyes. I have many skills, but sitting still and being silent are not traits I’m known for, so I was afraid: afraid of the judgment implicit in staring, afraid of the silence, afraid I wouldn’t have the transformative experience that had captivated those before me, afraid, afraid, afraid. Her lids opened and our eyes locked, not in a stare but in a friendly gaze. For the first few minutes, I thought only about who this woman was—a renegade, a feminist, an inspiration—but quickly realized that those things were more about her persona than the person. I discarded my preconceived notions and expectations and, as soon as I stopped thinking of her as an artist-celebrity, saw the woman behind the legend. We sat absolutely still in deafening silence, exchanging energy, and just being with each other. I’ve heard it said that couples married for decades can sit in silence and understand one another perfectly, but I’d never imagine that sort of intimacy could be possible between two total strangers. It is.

I could have stayed in that moment for hours but thought of my fellow line-mates, now friends, and decided it would be selfish to bask in this experience any longer. But, could I leave? It felt as rude as leaving a lecture in the middle. How would I leave? Abruptly just wouldn’t do, so I said good-bye and thanked her. More than thirty minutes had passed, thirty minutes of epic silence I’ll never forget.