10.3: Fauvism + Expressionism

- Page ID

- 65566

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Fauvism and Expressionism

These two movements opened the way for even greater experimentation with color and abstract form.

c. 1900 - 1930

Fauvism

Henri Matisse is the best known of this colorful, innovative group of painters.

c. 1905 - 1910

Fauvism, an introduction

Distinctive brushwork

Fauvism developed in France to become the first new artistic style of the 20th century. In contrast to the dark, vaguely disturbing nature of much fin-de-siècle, or turn-of-the-century, Symbolist art, the Fauves produced bright cheery landscapes and figure paintings, characterized by pure vivid color and bold distinctive brushwork.

“Wild beasts”

When shown at the 1905 Salon d’Automne (an exhibition organized by artists in response to the conservative policies of the official exhibitions, or salons) in Paris, the contrast to traditional art was so striking it led critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe the artists as “Les Fauves” or “wild beasts,” and thus the name was born.

One of several Expressionist movements to emerge in the early 20th century, Fauvism was short lived, and by 1910, artists in the group had diverged toward more individual interests. Nevertheless, Fauvism remains significant for it demonstrated modern art’s ability to evoke intensely emotional reactions through radical visual form.

The expressive potential of color

The best known Fauve artists include Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice Vlaminck who pioneered its distinctive style. Their early works reveal the influence of Post-Impressionist artists, especially Neo-Impressionists like Paul Signac, whose interest in color’s optical effects had led to a divisionist method of juxtaposing pure hues on canvas. The Fauves, however, lacked such scientific intent. They emphasized the expressive potential of color, employing it arbitrarily, not based on an object’s natural appearance.

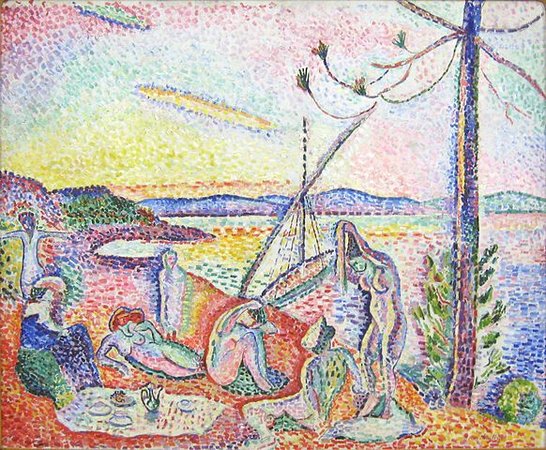

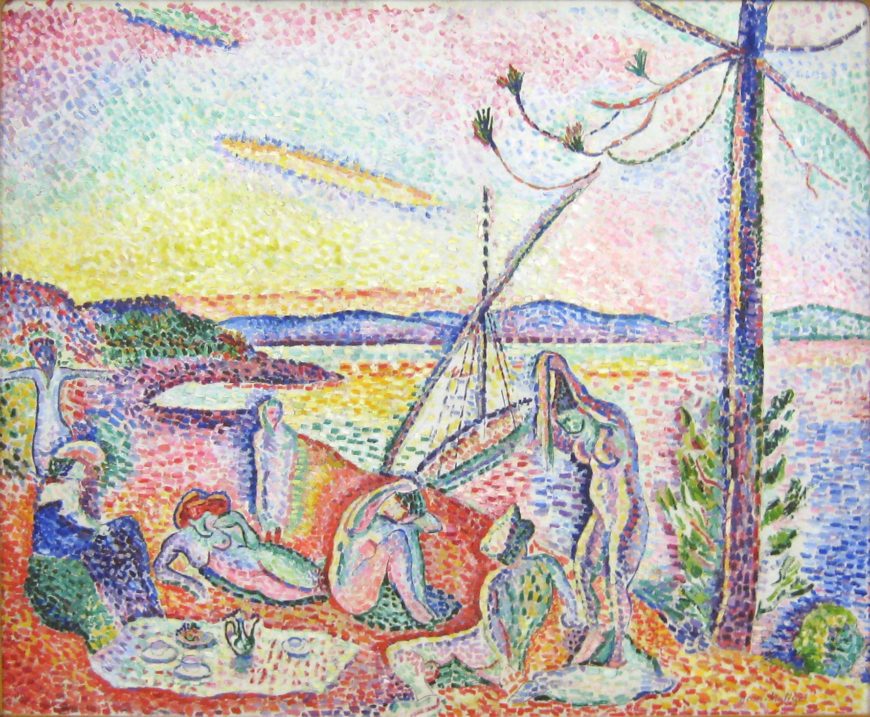

In Luxe, calm et volupté (1904), for example, Matisse employed a pointillist style by applying paint in small dabs and dashes. Instead of the subtle blending of complementary colors typical of the Neo-Impressionist painter Seurat, for example, the combination of fiery oranges, yellows, greens and purple is almost overpowering in its vibrant impact.

Similarly, while paintings such as Vlaminck’s The River Seine at Chatou (1906) appear to mimic the spontaneous, active brushwork of Impressionism, the Fauves adopted a painterly approach to enhance their work’s emotional power, not to capture fleeting effects of color, light or atmosphere on their subjects. Their preference for landscapes, carefree figures and lighthearted subject matter reflects their desire to create an art that would appeal primarily to the viewers’ senses.

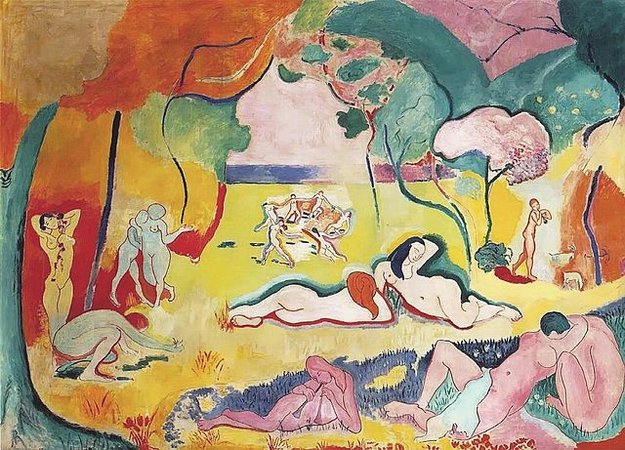

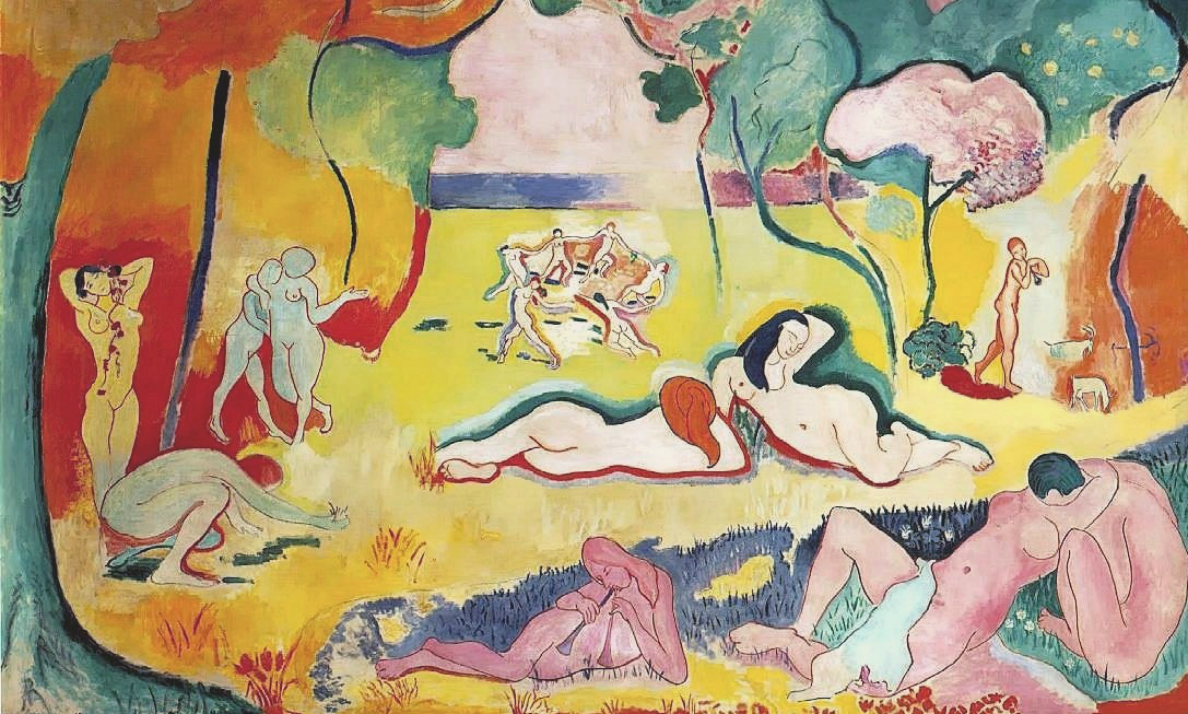

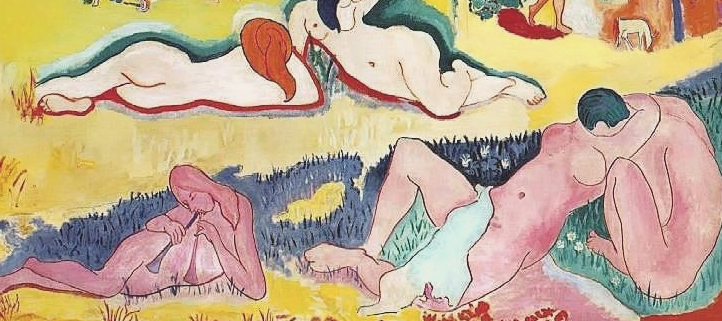

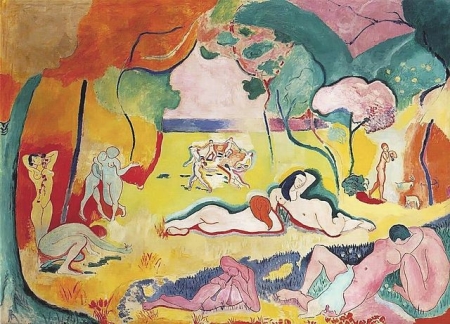

Paintings such as Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre (1905-06) epitomize this goal. Bright colors and undulating lines pull our eye gently through the idyllic scene, encouraging us to imagine feeling the warmth of the sun, the cool of the grass, the soft touch of a caress, and the passion of a kiss.

Like many modern artists, the Fauves also found inspiration in objects from Africa and other non-western cultures. Seen through a colonialist lens, the formal distinctions of African art reflected current notions of Primitivism–the belief that, lacking the corrupting influence of European civilization, non-western peoples were more in tune with the primal elements of nature.

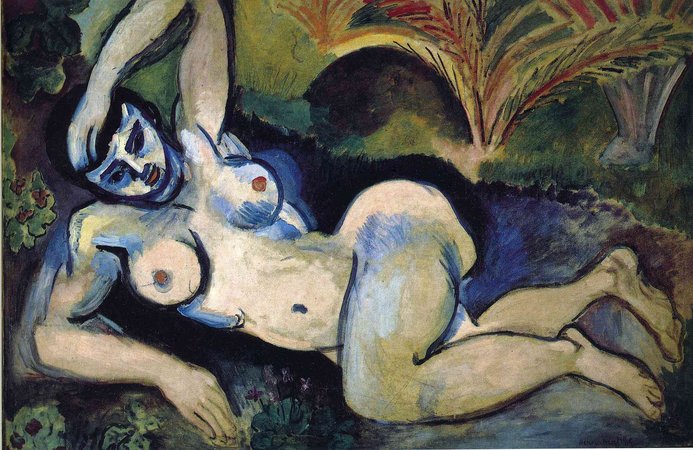

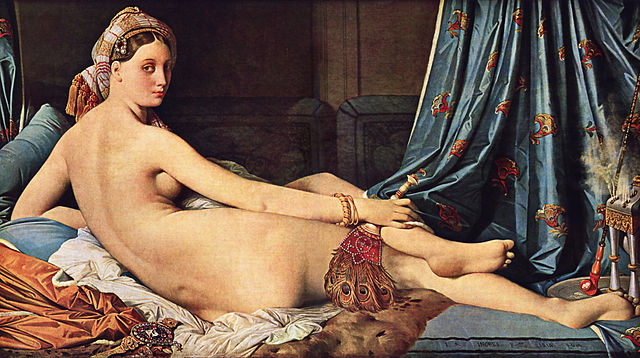

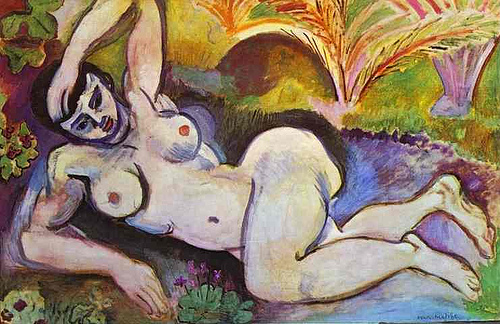

Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) of 1907 shows how Matisse combined his traditional subject of the female nude with the influence of primitive sources. The woman’s face appears mask-like in the use of strong outlines and harsh contrasts of light and dark, and the hard lines of her body recall the angled planar surfaces common to African sculpture. This distorted effect, further heightened by her contorted pose, clearly distinguishes the figure from the idealized odalisques of Ingres and painters of the past.

The Fauves’ interest in Primitivism reinforced their reputation as “wild beasts” who sought new possibilities for art through their exploration of direct expression, impactful visual forms and instinctual appeal.

Additional resources:

Fauvism at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

African Influences in Modern Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Fauve Landscapes and City Views

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Bright color and simplified form

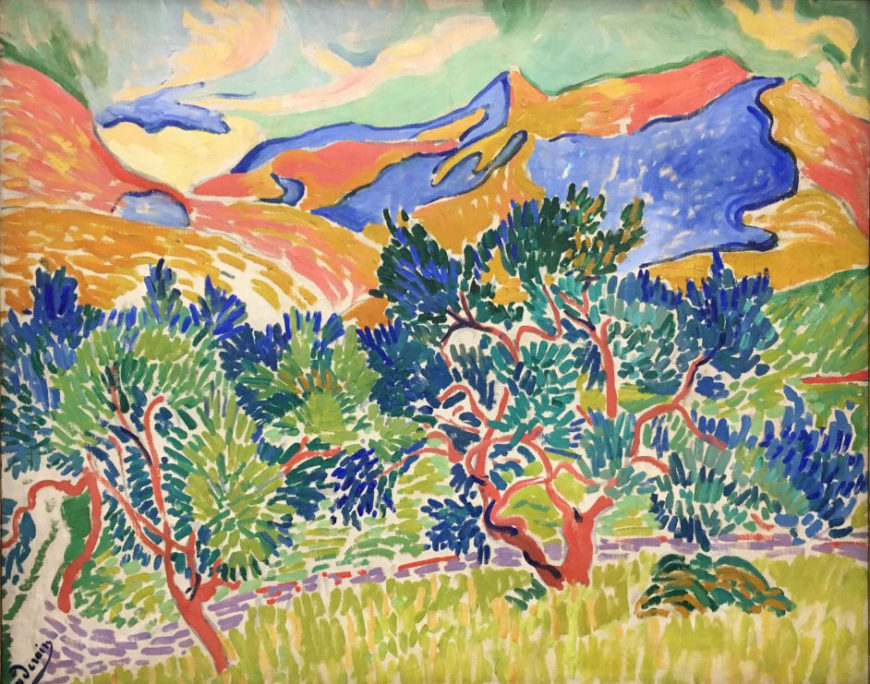

Varied patterns of brushstrokes define the landscape in André Derain’s Mountains at Collioure. Vivid blues and greens burst like fireworks from the twisted red branches of two trees rising up from a field of yellow-green vertical brushstrokes. A flowing horizontal line of blocky lilac strokes suggests a path or wall behind the trees, and diagonal strokes of green indicate a field rising towards the foothills. The mountains in the background are roiling forms painted in bright red, yellow, and blue under a pale green and yellow sky. Colors do not fade with distance according to the rules of atmospheric perspective. Their undiminished intensity makes the scene appear flat and decorative, just colors arranged in patterns on the surface of the canvas.

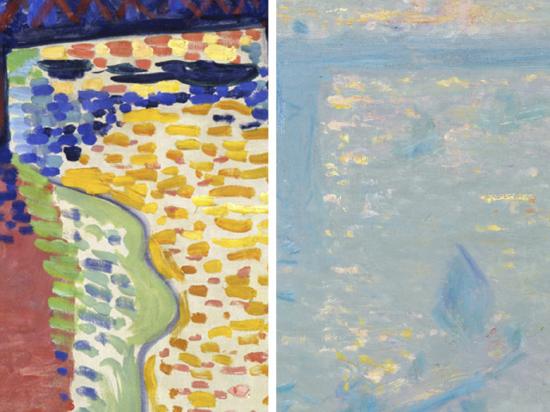

Made in the summer of 1905 when Derain was painting in the south of France with Henri Matisse, Mountains at Collioure is a quintessentially Fauve landscape with its bright, unmodulated color and simplified forms. Both painters developed styles that synthesized the work of their Post-Impressionist predecessors. Matisse had previously used a technique of regularized brushstrokes derived from the Neo-Impressionists in Luxe, Calme et Volupté. He abandoned this technique for the more liberated and suggestive approach of Landscape at Collioure, in which the paint is applied in loosely patterned and widely separated brushstrokes to raw canvas.

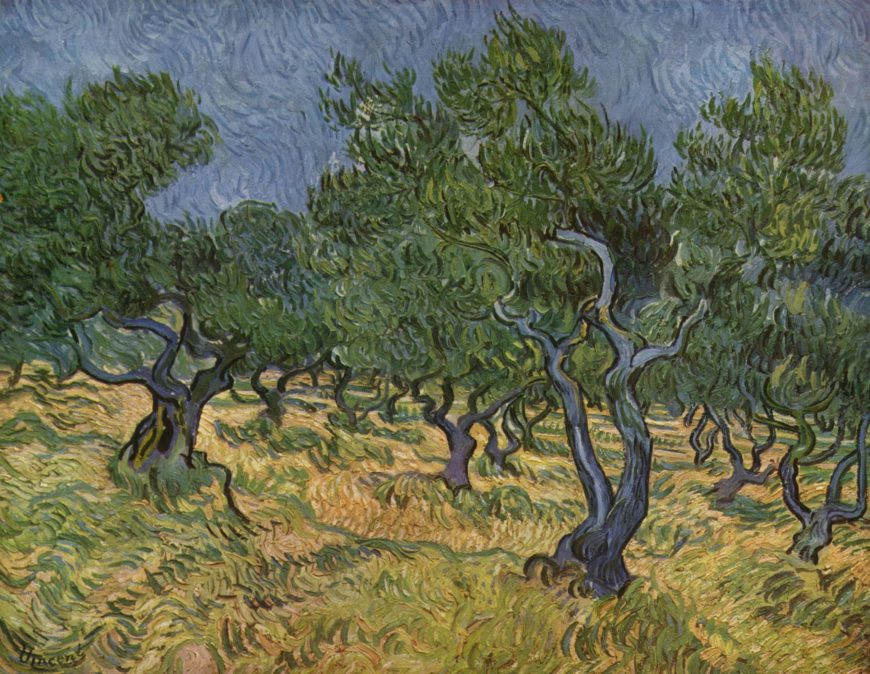

A greater degree of abstraction

Derain’s Mountains at Collioure is more carefully structured than Matisse’s contemporary landscape. Both paintings use brilliant color and visible brushstrokes to create surface patterns, but Derain distinguished foreground from background by distinct differences in paint application. The foreground trees with their thickly painted, regular patterns of leaves were depicted in the style of van Gogh, while the undulating flat colored planes of the background mountains echoed Gauguin’s abstraction of landscape forms.

Like the Post-Impressionists, Derain and Matisse intensified or even disregarded local colors in their landscapes while emphasizing surface patterns and textures. What distinguished their paintings from their predecessors and prompted an art critic to call them “Fauves” (wild beasts) was their use of more simplified color palettes, more liberated and inconsistent brushwork, and a greater degree of abstraction in both form and color.

Scenes of modern leisure

Landscapes and city views were the favored subjects of the Fauve painters. They followed the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in depicting popular vacation spots and scenes of modern leisure. These included the Paris suburbs and beach resorts of Normandy favored by the Impressionists, as well as Mediterranean towns in the south of France painted by Cézanne, van Gogh, and Gauguin. Many of their compositions of these vacation spots are very similar to contemporary postcard views of the same locations. Their paintings are, however, far from photographic. All of the Fauve painters used a liberated style to create paintings that seem to celebrate the pleasures of painting as much as the pleasures of life. They embraced both the decorative qualities of painting — the abstract arrangement of colors and shapes—and the employment of liberated, expressive brushwork.

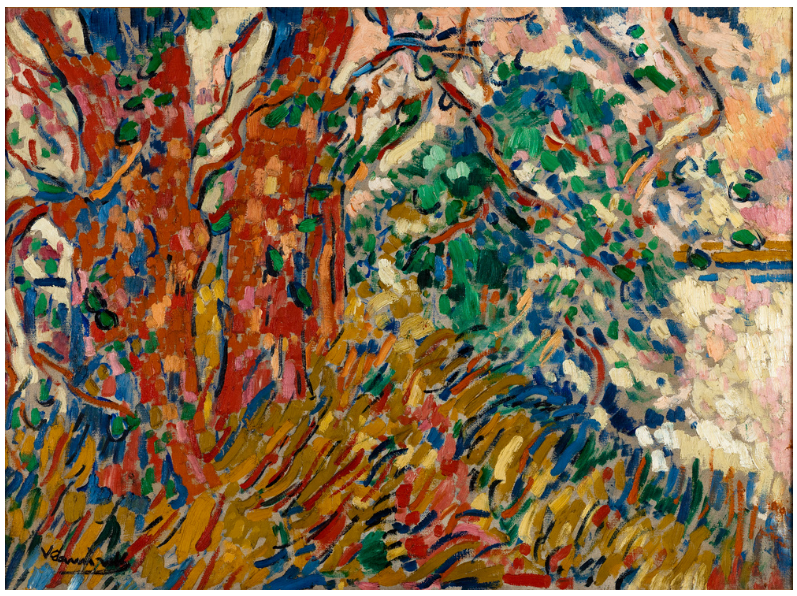

The wildest Fauve

Maurice Vlaminck is often considered the most truly Fauve painter of the group. A close friend of Derain’s, he was largely self-taught and a devoted admirer of van Gogh’s work. He painted the small towns and landscapes near the Paris suburb of Chatou where he lived. His use of intense color, thick paint, and simplified forms is very similar to van Gogh’s style. Vlaminck, however, applies paint much more randomly and chaotically than van Gogh, who meticulously organized his canvases into regularly textured patterns of repeating brushstrokes.

In Vlaminck’s The Banks of the Seine at Chatou, the blocky red tree trunks rise up from ochre, red, and bright blue stripes of long grass. Small patches of vibrant color pepper the upper portion of the canvas like a mosaic suggesting a tangle of branches and leaves swirling above the gleaming river on a bright windy day.

Fauve painters tended to use a limited range of colors, emphasizing the brightest shades of the primaries (red, blue, and yellow) as well as the secondaries green and orange. Vlaminck took this restricted palette further than Derain and Matisse, and often used his colors straight out of the tube without mixing them. In Bougival he organizes the landscape in broad color areas: red for the foreground field, yellow leaves for the middle ground, green trees in the background, and blue hills and water in the distance. The paint is applied with simple, blunt strokes to create a powerful image of a fall day in the countryside.

London views

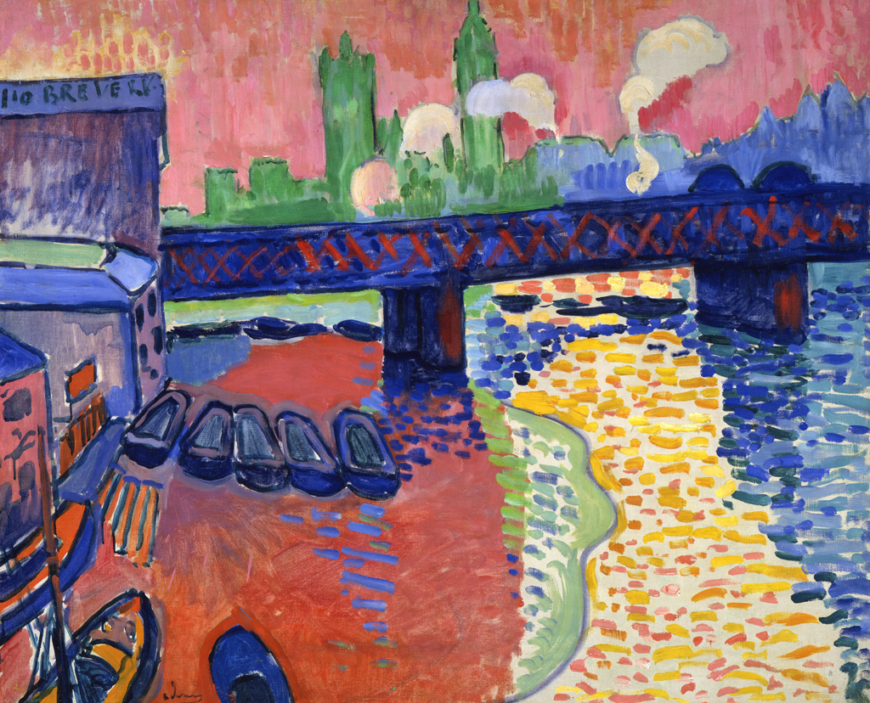

Derain’s Charing Cross Bridge is one of a series of paintings he was commissioned to make of London views. Claude Monet had recently exhibited an Impressionist series of London scenes, and Derain painted many of the same subjects in an aggressive Fauve style.

Consistent with the Impressionist interest in recording specific atmospheric effects, Monet’s Charing Cross Bridge depicts the boats, bridge, and buildings dissolving into a bright haze of foggy light and visible brushstrokes. Derain’s painting, in stark contrast, makes no attempt to convey the effects of light in a realistic manner; instead, it is a riotous celebration of color and free brushwork. Bright reds, blues, and yellows dominate, with a glowing pale green shape indicating the distant Houses of Parliament.

Monet used delicate, textured brushstrokes to depict touches of light on the water, clouds of steam and swirls of fog. Derain’s brushstrokes are like colored bricks representing the patterns of light and reflections on the water’s rough surface. The sky, rendered with tightly packed vertical brushstrokes, is an apocalyptic orange-red, while the left side of the river is an even more intense shade of deep red with scattered light and dark blue strokes suggesting reflections.

Deep and bright blues outline the boats and buildings, and the bridge itself is a deep blue marked with a row of red of X’s that slashes across the upper portion of the canvas. An area of yellow and orange brushstrokes on bare canvas creates a visual path of light on the river flowing under the bridge to the distant horizon. Flat pale clouds of smoke rise above the bridge like cartoon bubbles. The subject is recognizable, but the colors and simplifications of form render it hallucinatory. Next to Derain’s wildly exaggerated vision, Monet’s Impressionist view looks extremely refined and even old-fashioned with its nuanced rendering of reflected light and color.

Busy street scenes

Most of Derain’s London paintings depict river views, but he also painted a crowded shopping street. In Regent Street the simplifications of color and form create a compelling image of the city’s commercial district. Horse-drawn carriages, a bicycle, and pedestrians fill the roadway. We see shop signs and posters, flags and street lights. A man wearing advertising posters dominates the lower left corner, while fashionably dressed shoppers occupy the right as they move down the sidewalk towards us. Derain’s Fauve colors and shapes are here an effective means to render the chaos of the modern city.

Raoul Dufy painted many scenes of the beach resorts in Normandy with bright colors and simplified forms. Rather than using the intense, often non-naturalistic colors of the leading Fauves — Matisse, Derain and Vlaminck — Dufy chose subjects that were themselves brightly colored, such as advertising billboards and the flag-decorated streets of Bastille Day. His approach was closer to Impressionism, but like his fellow Fauves he embraced simplified form, brilliant colors and direct visible brushwork.

André Derain, The Dance

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

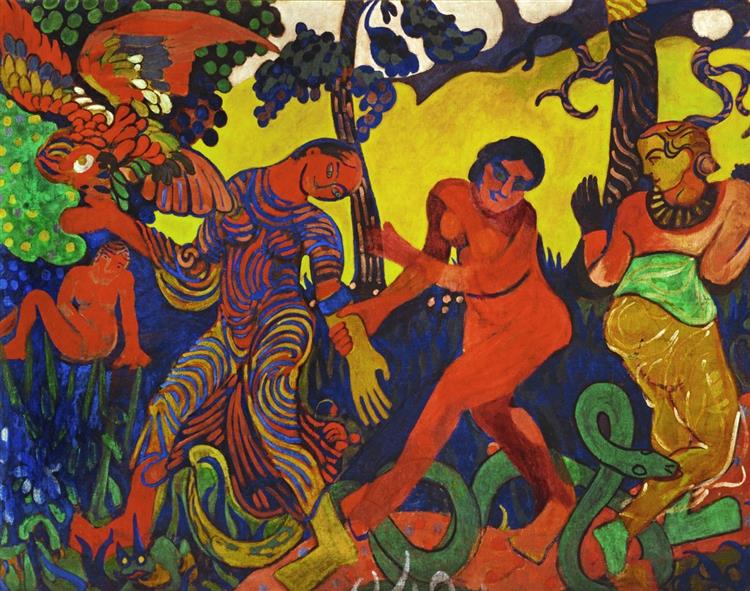

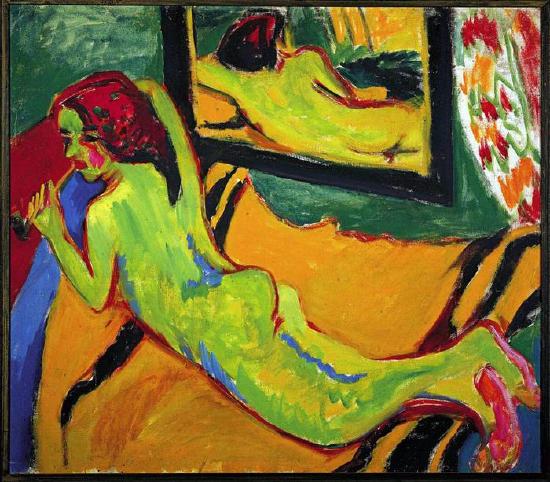

André Derain’s The Dance is an ambitious and remarkably eclectic painting that combines references to multiple European and non-European sources. The highly saturated palette of the primary colors (red, blue, and yellow), with the addition of the secondary green, is characteristic of Fauvism, a pictorial style associated with wild and unrestrained expression. In its attempt to synthesize a disparate collection of sources and references, The Dance testifies to the multi-layered, hybrid approach modern artists adopted as they attempted to create art works imbued with so-called primitive qualities.

Exotic and primitive motifs

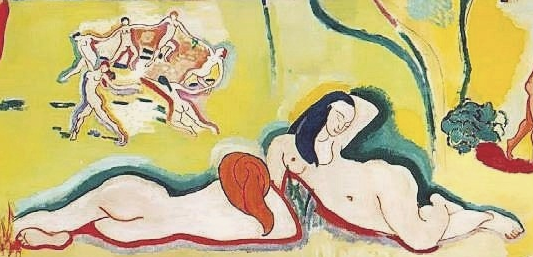

At seven and a half feet wide, The Dance is as large as Henri Matisse’s Fauve masterpiece Bonheur de Vie/Joy of Life, painted the same year. The subjects of the two paintings, female figures cavorting in an imaginary landscape, are similar, and both paintings suggest a fundamental union between humans and nature. Matisse’s references are, however, classical and Arcadian, while Derain’s are more exotic and primitive.

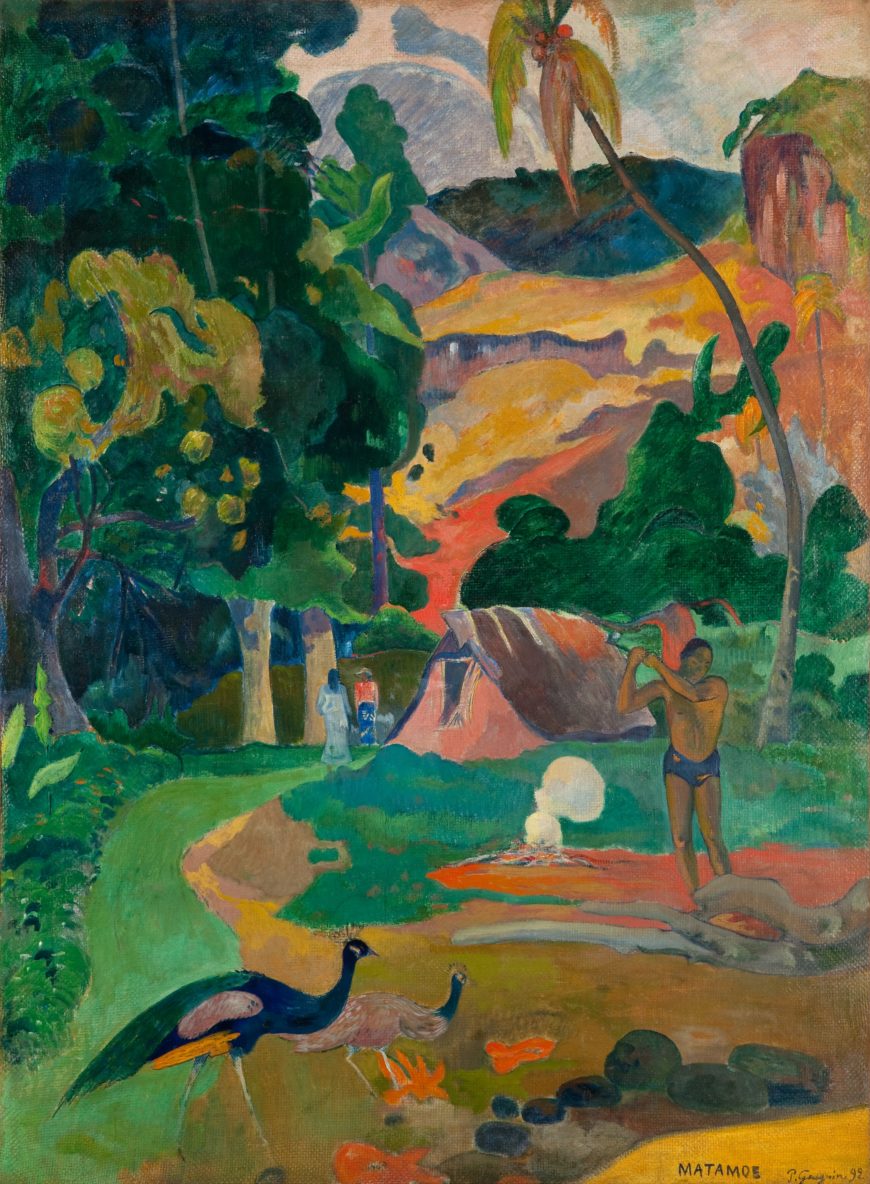

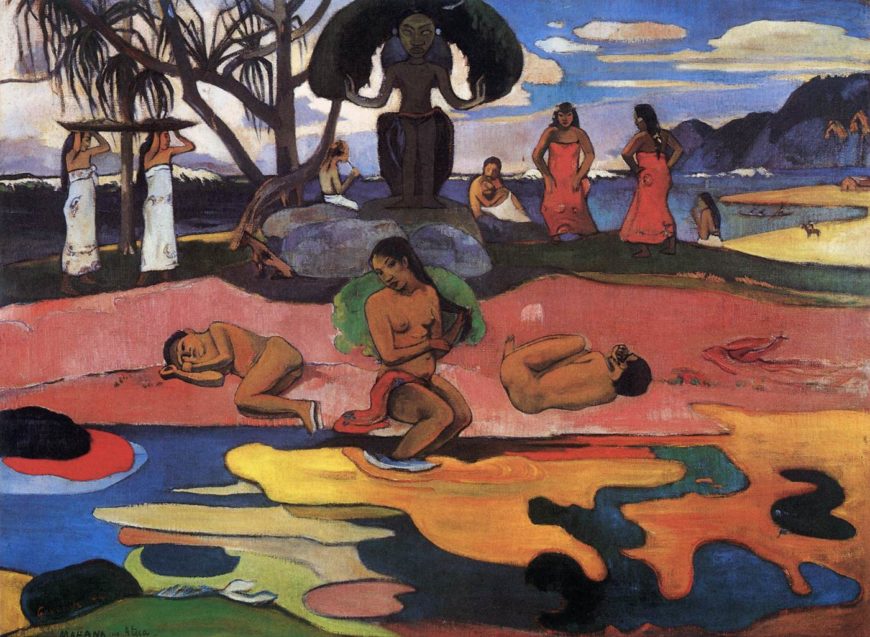

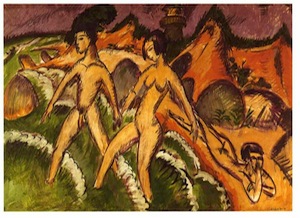

The Dance echoes the paintings of Paul Gauguin in both style and subject matter. Like Gauguin, Derain uses simplified forms and unmodulated areas of bright color in a composition that emphasizes flat, decorative qualities. The subject is overtly exotic with nude and partially nude women displayed in a fantastic landscape along with a huge scarlet macaw and a green snake. These creatures allude to both their non-European native habitats and to an Edenic world where humans live in harmony with nature.

Derain also followed Gauguin in his eclectic combination of cultural references. However, unlike his predecessor, whose primitivist pastiches resulted from a sincere commitment to the discovery of universal symbols and spiritual forms, Derain’s eclecticism is a more superficial adoption of varied exotic motifs. Art historians have identified references to Indian carved reliefs, African masks, Romanesque sculptures, European folk art, and Japanese prints in The Dance. The figure on the right is directly derived from another painting of “exotic” non-European women, Eugène Delacroix’s Women of Algiers. The black woman on the right in Delacroix’s imagined harem scene has become a racially ambiguous, mostly nude blonde woman with multi-colored skin in Derain’s Fauve painting.

New and exotic forms of dance

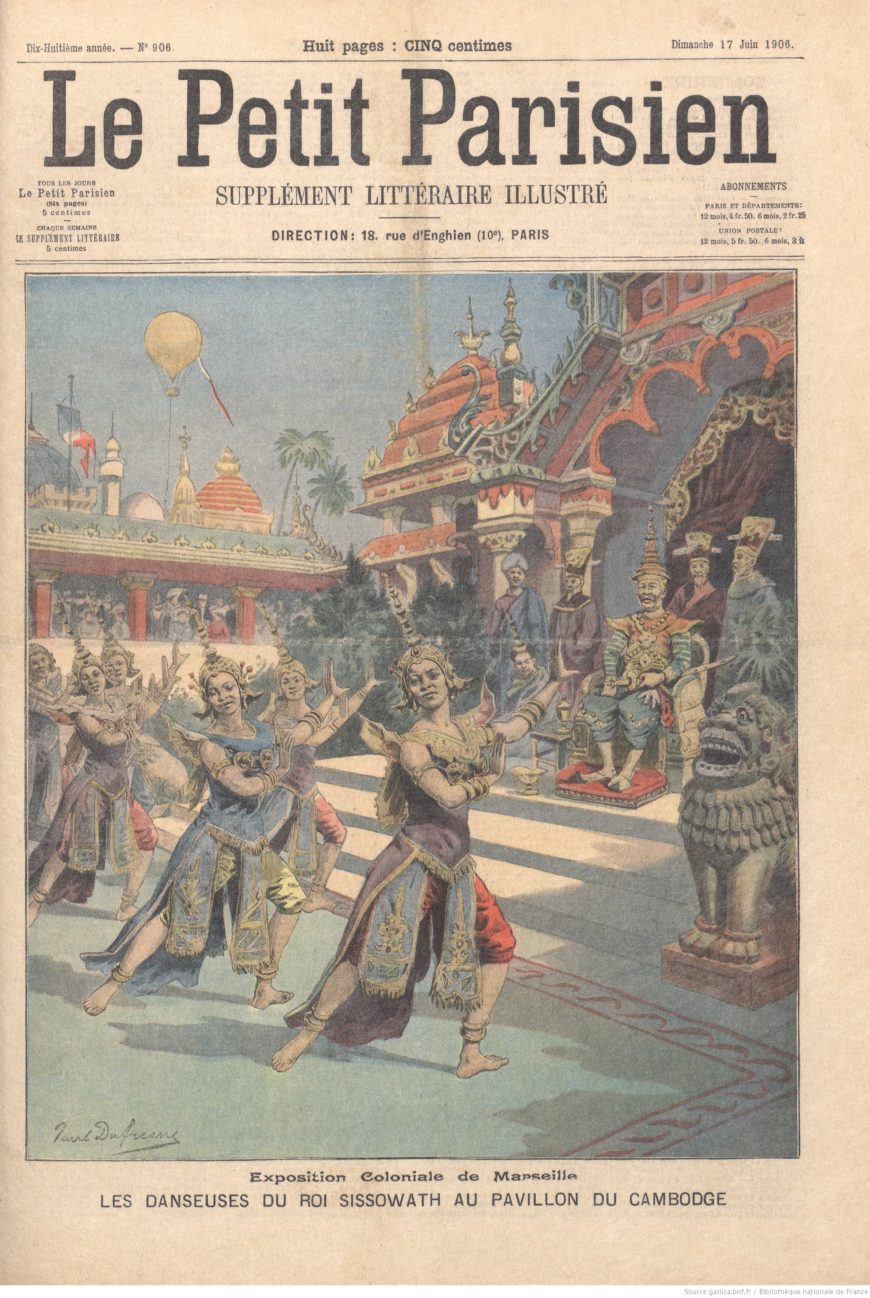

The Dance belongs to a well-established tradition of imagined primitivist scenes in European art that feature sexualized images of non-European women. It is also specifically of its time in its focus on dance. At the turn of the 20th century there was widespread interest in non-western dance forms. International expositions often included performances of traditional court and folk dances from non-western countries. Derain saw the Cambodian court dancers at the 1906 Colonial Exposition in Marseille around the time that he painted The Dance.

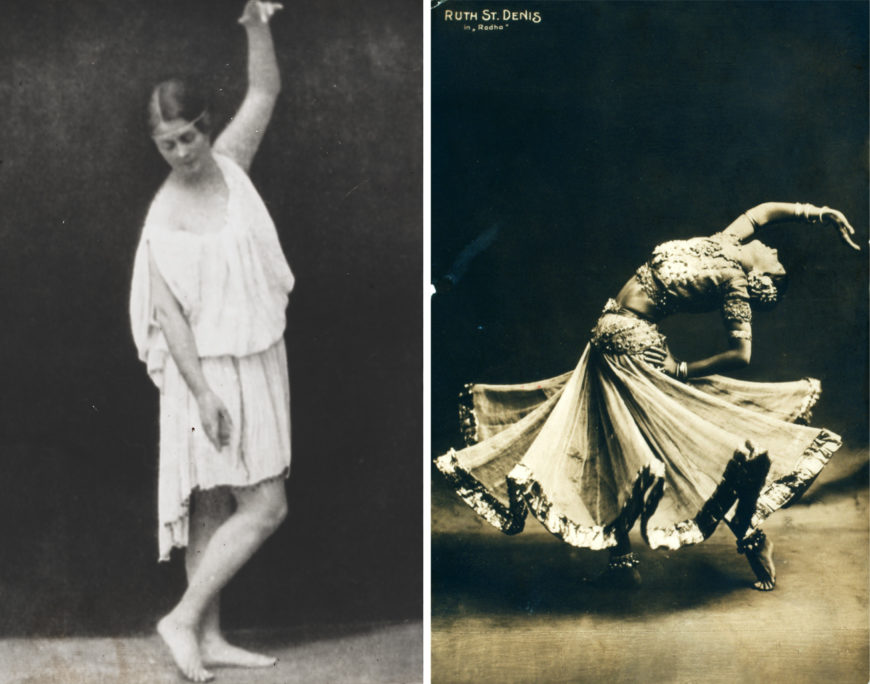

Modern dance also had its origins during this period. Dancers such as Loïe Fuller and Isadora Duncan rejected the stylized forms of classical ballet and focused on the body as a vehicle of direct, unfettered expression. Duncan saw her dancing as an expression of universal natural forces linked to Ancient Greece. Another popular dancer of the period, Ruth St. Denis, created “exotic” dances loosely based on Indian, Egyptian, and Babylonian mythology.

Fauvism and African art

Cultural eclecticism is a hallmark of European modern art in the early years of the 20th century, and Derain and his fellow Fauves Maurice Vlaminck and Henri Matisse were significant contributors to the trend. They were among the first modern artists to acquire African masks and sculptures, and Derain visited ethnographic collections in Paris and London to see non-western artifacts. These became increasingly available for purchase during this period as a consequence of Europe’s escalating investment in its overseas colonies.

With its combination of references to many different cultures and styles, Derain’s The Dance is a prime example of the period’s cultural eclecticism. Aggressive primary colors, simplified non-naturalistic forms, and an emphasis on decoration combines with eroticized images of women in nature to signify the primitive.

For many modern artists the use of intense colors and rudimentary forms was considered a means to regain contact with the natural energies of the universe and express themselves directly. Their appreciation of the non-western works they collected was primarily formal (in other words, concerned with their appearance, and not their cultural context), and they adopted similar abbreviated and simplified forms in their own works.

Matisse remarked on the difference between the European approach to sculpting the human body and the African sculptures he saw in a Paris curio shop around 1905. European sculptors were interested in the naturalistic representation of musculature, while the African sculptures were “made in terms of their material, according to invented planes and proportions.\(^{[1]}\)”

Primitivist styles and subjects

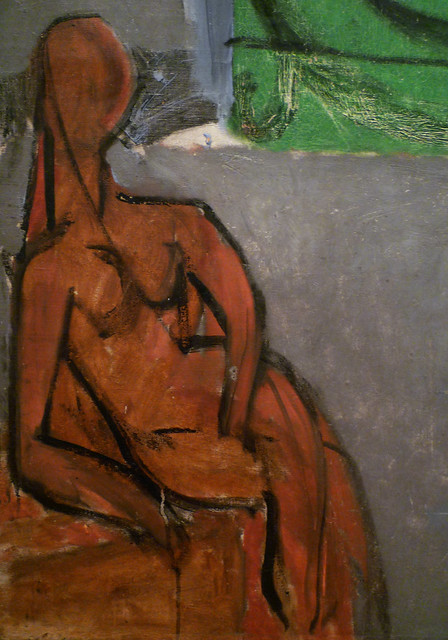

Both Matisse and Derain made sculptures of human figures that radically abstracted the body in response to the African sculptures they encountered. Derain’s roughly-carved sandstone Crouching Man simplifies and reduces the human figure to a cube, using exaggerated forms to convey a mood of introspective despair.

Matisse’s more conventional Reclining Nude also uses simplification and exaggeration of body parts, as well as twisting the angle of the head, to explore alternative strategies for representing the human figure.

Matisse’s painting The Blue Nude was developed from similar formal concerns. The traditional European subject of the reclining nude, often associated with Orientalist fantasies in the 19th century, is here situated outdoors in a vaguely exotic setting suggested by the palm-like plants in the background. As in Matisse’s sculpture, the shapes of the body are simplified and exaggerated to emphasize the buttocks and breasts.

Matisse’s materials—paint on canvas—are emphasized, as is the artist’s labor. We see his brushstrokes and, in places, the canvas underneath the paint. Matisse has not covered up changes he made to the figure, giving us the sense that we are seeing a work still in progress — further enhancing our awareness of the painting’s materiality. Subtitled Memory of Biskra, after a town in Algeria Matisse had visited, the painting is the result of an encounter between European erotic fantasy and abstracted forms derived from African sculpture.

In Blue Nude and The Dance, Matisse and Derain used a liberated Fauve approach to color and form to depict female figures in an exotic setting. They combined what was considered a crude and primitive style with references to so-called primitive cultures. The paintings demonstrate how closely the Fauve painters’ concerns were bound up with both primitivist fantasies of enjoying leisure and women in tropical landscapes and the formal qualities associated with primitivism — simplified drawing, flattened space, and bright decorative color.

Notes:

- Quoted in Sarah Whitfield, Fauvism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), page 161.

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse, Luxe, calme et volupté

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Henri Matisse, Luxe, calme et volupté, 1904, oil on canvas, 37 x 46″ (Museé d’Orsay, Paris)

Key points:

- Luxe, calme et volupté borrows from the Neo-Impressionist style in its brushwork, but does not adopt Neo-Impressionism’s approach to color.

- Rather, this painting anticipates the Fauves’s imaginative use of expressive color.

- Color and form are key ways that early 20th-century artists began to abandon representation for abstraction.

Painted while the artist stayed with the pointillist painter, Signac, at his home in Saint-Tropez on the Côte d’Azur. Matisse’s title comes from Charles Baudelaire’s poem, “L’invitation au voyage (Invitation To A Voyage)” from his collection, The Flowers of Evil. “Luxe, calme et volupté” translates just as it sounds in English: “Luxury, calm, and voluptuous(ness).”

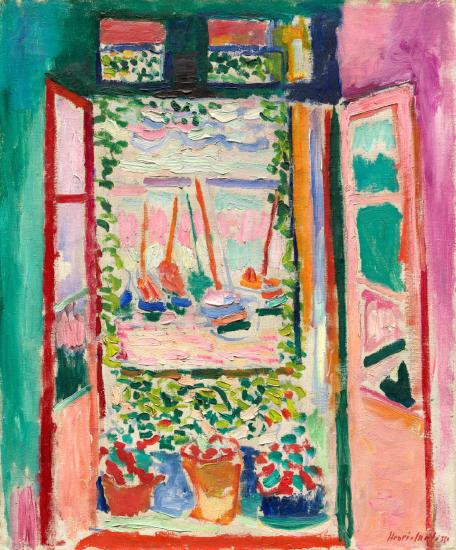

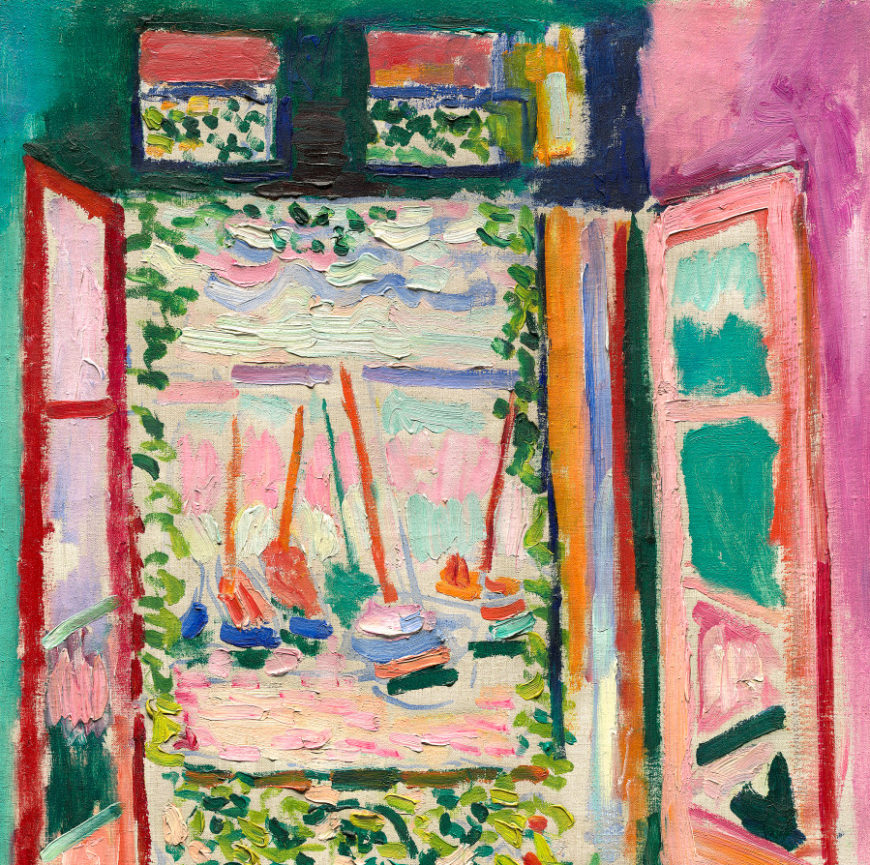

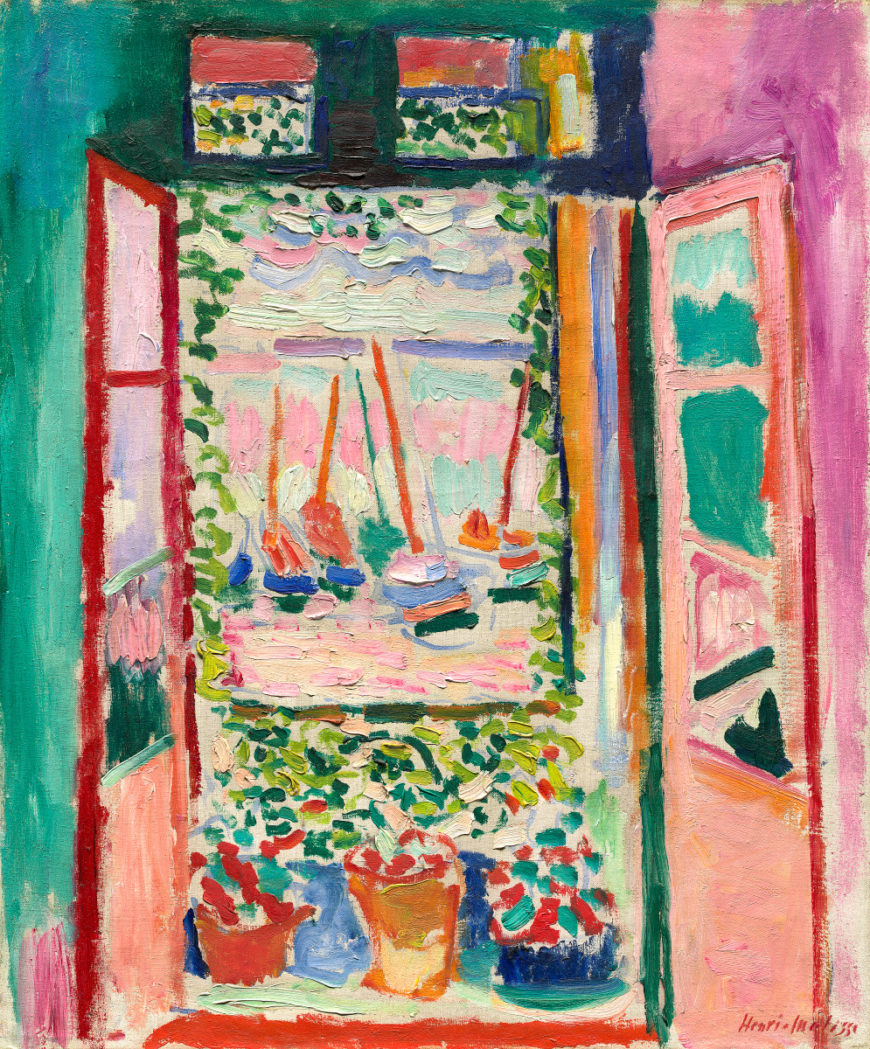

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

An explosion of color

In Henri Matisse’s Open Window, Collioure the casements of a large French window project toward us to reveal an explosion of brilliant Mediterranean color. The paint is applied very loosely; even in reproduction we can see almost every brushstroke. The painting looks as if it were made yesterday, and in some places (like the lower right where bare canvas is visible), seems unfinished. We can envision Matisse’s working process brushstroke by brushstroke, and we are there with him responding with excitement to the wealth of color and light at a Mediterranean seaside town in summer.

Although the style implies a rapid or even slipshod painting process, Open Window, Collioure was carefully orchestrated in every aspect, from the composition to the color relationships and the paint application. The window is placed slightly off center to the left, which gives the composition a casual feeling, in keeping with the slapdash quality of the brushstrokes. Underpinning this seeming casualness, however, is a calculated structure of repeating and nested rectangles that creates both a strong surface pattern and a series of internal “windows.”

The brightest area of the painting, the central view of boats in harbor, is framed by some of the painting’s darkest tones in both the literal window frame and a pattern of green leafy vines. Surrounding this central view are multiple subsidiary window panes. Two transom windows at the top frame more views of the porch window and vines. Glass panes in the casement windows reflect both the view outside the French window and the colors of the walls.

Brilliant colors ricochet and echo across the canvas. Matisse uses complementary color contrasts throughout, setting off his glowing reds and pinks with cool greens. The walls are fuchsia and green, and the upper window panes of the casements reflect the opposing wall’s color, enhancing the intensity of the hues by contrast. A similar mutually intensifying contrast of colors appears where the vertical stripe of vivid orange paint, perhaps representing a curtain, is brushed next to the dark ultramarine strip of the window frame. Varied patterns of pale pink and turquoise brushstrokes represent sea and sky in the view out the window.

Denying the illusion of depth

Open Window, Collioure engages with, and ultimately undermines, the post-Renaissance conception of a painting being like a window. Matisse’s drawing of the window emphasizes its role as a framing device located in a three-dimensional space. The casements open inward, creating a perspectival view leading to the window opening. The balcony with flower pots on the floor is a shallow intermediate space between the room and the view of the harbor, which reaches to the horizon. However, all of these indications of spatial depth are negated by color and paint application, which emphasize the flat surface of the canvas and fail to create a convincing illusionistic scene. We never forget that we are looking at a painting and not out a window.

The highly visible brushstrokes and areas of unpainted canvas are the most obvious way Matisse denies us the illusion of reality, but his use of color is also important. Not only is it extremely bright and flat, lacking the chiaroscuro modulations traditionally used to suggest volume and depth, it also repeatedly subverts clear differentiation of foreground and background. For example, the distant masts of the boats in the harbor and the much closer verticals of the window frames create a surface pattern of bright orange and red verticals. The more distant reds and oranges are not muted to indicate depth through atmospheric perspective. Similarly, the dark blue and green brushstrokes depicting the hulls of the boats are echoed by the dark blue and green paint strokes used to indicate edges of the window frames and various objects in the foreground.

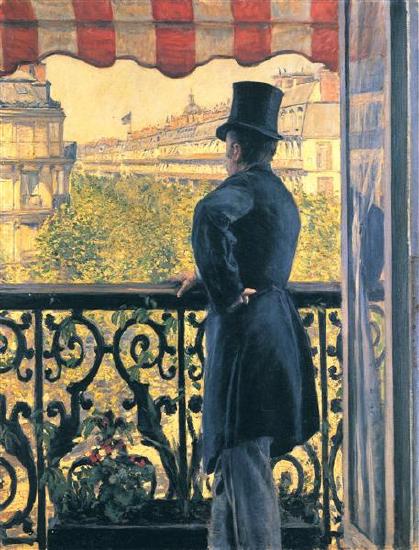

A glance at Gustave Caillebotte’s compositionally similar Man on a Balcony: Boulevard Haussmann shows how completely Matisse undermines the depiction of perspectival depth. Caillebotte’s naturalistic scene clearly distinguishes between the darker dominating foreground space of the balcony and the vista of sunlit buildings receding down the boulevard. In Matisse’s Open Window, Collioure, the distant harbor view dominates, and it is framed by the window as if it were itself a painting. It has no defined spatial relationship to the foreground, unlike Caillebotte’s vista down the boulevard where we can determine the relation of the balcony to the view with precision.

The 1905 Salon d’Automne

Open Window, Collioure was one of several paintings Matisse exhibited with a group of friends at the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris. A sympathetic art critic, Louis Vauxcelles, inadvertently named the group when he described the effect of their brilliantly colored paintings hanging on the walls surrounding two classicizing sculptures as being like Donatello among the fauves (wild beasts). The name came to reflect the extreme public reaction to the paintings, which were widely considered disturbing and outrageous. Conservative critics mocked the paintings in the press, but the Fauve painters ultimately profited from the notoriety and found dealers, critics and collectors who supported their work.

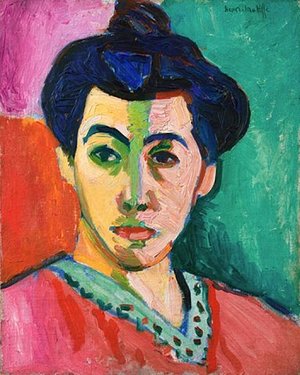

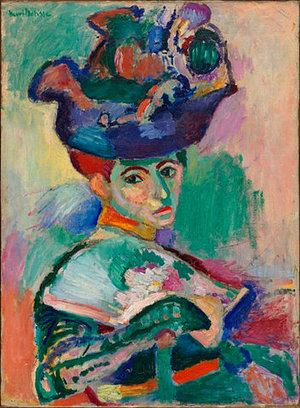

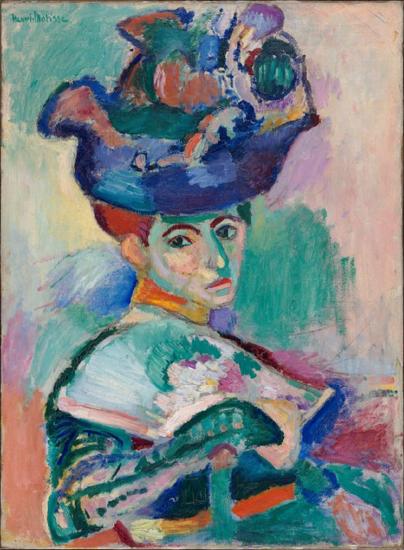

Matisse was the leader of the group, and his Woman with a Hat was considered the most scandalous painting in the “fauve cage” at the exhibition. The use of brilliant complementary colors, prominent brushwork and seemingly unfinished areas is very similar to Open Window, Collioure, but their effect in this traditionally-composed portrait of a woman was unsettling.

The crude dabs of paint, harsh simplified features, and the rendering of the shadows on the face in brilliant turquoise were all startling, even for viewers used to the painterly abbreviations and bright colors of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The faces in Morisot’s Impressionist Summer’s Day, and van Gogh’s Post-Impressionist Self-Portrait lack realistic detail and call attention to the artists’ brushstrokes, but the color used in both paintings remains well within the range of naturalistic depiction compared to Matisse’s Woman with a Hat.

In addition to the aggressively non-naturalistic tones in the face, Matisse’s style in The Woman with the Hat is raw and disjunctive. The painting looks unfinished and unresolved, with some parts painted in heavy impasto and others barely brushed in. The Salon jury tried to persuade him to retract the painting from his submission, but Matisse refused, indicating that he believed the painting to be finished and ready for exhibition.

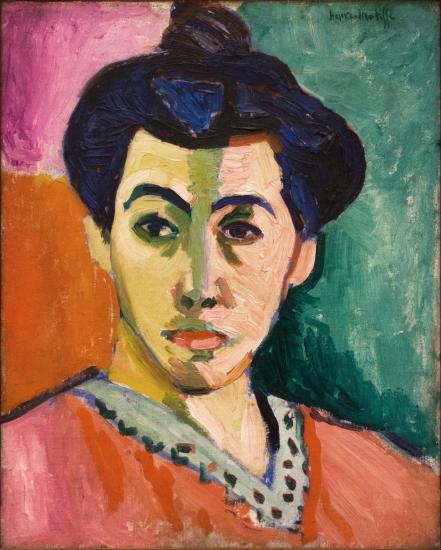

The expressive potential of color

Matisse’s paintings in the 1905 Salon d’Automne with their disjunctive brushwork and tempestuous color were his most radical Fauve works. After the exhibition, Matisse continued to use bright non-naturalistic color, but his paint application became more consistent and his colors less chaotic. In Portrait of Mme. Matisse: The Green Line and Bonheur de Vivre the brilliant colors are organized into larger areas to maximize their intensity. Over the course of the next few years he became increasingly concerned with pictorial harmony.

In his 1908 “Notes of a Painter” Matisse wrote:

The entire arrangement of my picture is expressive . . .. Composition is the art of arranging in a decorative manner the diverse elements at the painter’s command to express his feelings. In a picture every part will . . . play its appointed role. . . . A work of art must be harmonious in its entirety. . . .Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” [1908] trans. J. D. Flam, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory 1900-2000 (London: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 70-71.

Throughout his career Matisse was dedicated to the expressive potential of color: “My choice of colors is based on observation, on sensitivity, on felt experiences. . . . I simply try to put down colors which render my sensation . . . a moment comes when all the parts have found their definite relationships . . ..”\(^{[1]\)

Although “Notes of a Painter” was written some years after Matisse painted Open Window, these passages indicate that he was balancing three different projects. He was attempting to be responsive to (1) the perceptual information he received from the motif, (2) the feelings that he got from it, and (3) the decorative formal qualities of the work of art itself. Keeping all three in play allows The Open Window to read simultaneously as a window into real space, a flat plane covered with harmonious color, and an expression of the joyful warmth of a Mediterranean day.

The Open Window was one of Matisse’s most radical Fauve paintings, but it is also an example of his enduring dedication to expressive color and pictorial harmony. Matisse painted many windows throughout his career, including The Blue Window and The Piano Lesson, and they reflect the variations in his style over time. The Open Window of 1905 represents the barely restrained exuberance of his Fauve period, while a second version of Open Window at Collioure painted in September 1914 just after the start of World War I conveys the mood of those dark days.

Notes:

- Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter” [1908], trans. J. D. Flam, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory 1900-2000, (London: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 70-71.

Additional resources:

The Open Window, Collioure at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

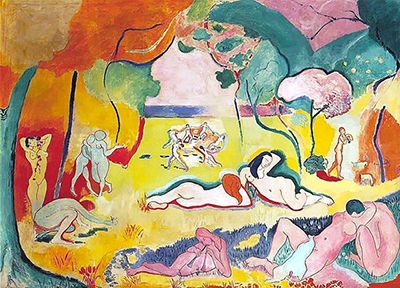

Henri Matisse, Bonheur de Vivre

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

The Joy of Life

In 1906, Henri Matisse finished what is often considered his greatest Fauve painting, the Bonheur de Vivre, or the “Joy of Life.” It is a large-scale painting depicting an Arcadian landscape filled with brilliantly colored forest, meadow, sea, and sky and populated by nude figures both at rest and in motion. As with the earlier Fauve canvases, color is responsive only to emotional expression and the formal needs of the canvas, not the realities of nature. The references are many, but in form and date, Bonheur de Vivre is closest to Cézanne’s last great image of bathers.

Matisse and his sources

Like Cézanne, Matisse constructs the landscape so that it functions as a stage. In both works trees are planted at the sides and in the far distance, and their upper boughs are spread apart like curtains, highlighting the figures lounging beneath. And like Cézanne, Matisse unifies the figures and the landscape. Cézanne does this by stiffening and tilting his trunk-like figures. In Matisse’s work, the serpentine arabesques that define the contours of the women are heavily emphasized, and then reiterated in the curvilinear lines of the trees.

Matisse creates wildly sensual figures in Bonheur de Vivre, which show how he was clearly informed by Ingres’s odalisques and harem fantasies.

Additionally, Matisse references Titian. For like Titian’s Bacchanal of the Andrians, the scene depicted in Bonheur de Vivre is an expression of pure pleasure. Here is a place full of life and love and free from want or fear. Instead of a contemporary scene in a park, on the banks of the Seine, or other recognizable places in nature, Matisse has returned to mythic paradise.

Radicalism, or how to color outside the lines

But do not be misled by his interest in myth—Matisse is not joining in with Bouguereau or any other Salon artist. This is the epitome of Fauvism, a radical new approach that incorporate purely expressive, bright, clear colors and wildly sensual forms. Matisse’s painting s perhaps the first canvas to clearly understand Cézanne’s great formal challenge, and to actually further the elder master’s ideas. In fact, despite its languid poses, Bonheur de Vivre was regarded as the most radical painting of its day. Because of this, Matisse became known, briefly, as the most daring painter in Paris.

So what was daring about this canvas? Here is one key issue: unlike the paintings by Cézanne, Ingres, or Titian, Matisse’s work does not depict forms that recede in the background and diminish in scale. If you study the figures in the foreground and the middle ground of Bonheur de Vivre, you will notice that their scale is badly skewed. The shift of scale between the player of the double flute (bottom center) and the smooching couple (bottom right) is plausible, if we take the musician to be a child, but what of the giants just behind them? Compared to the figures standing in the wings, who are obviously mature women (middle ground left), these center women are of enormous proportion. They are simply too big to make sense of within the traditional conventions of Western painting.

Perspective, patronage and Picasso

So why has Matisse done this? How could these shifts of scale make sense? Have we seen anything like this before? Well, in a sense we have. Cézanne’s painting ruptured forms in order to accurately explore vision as experienced through time and space—in other words, forms look different depending on where we are in relation to them.

In fact, this exploration of vision through space is the key to understanding Matisse’s work. By incorporating shifting perspectives, he brought this idea to a grand scale. Put simply, Matisse’s shifting scale is actually the result of our changing position vis-à-vis the figures. As a result of his experimentation with perspective, the viewer relates differently to the painting and is required to “enter” the scene. It is only from the varied perspectives within this landscape that the abrupt ruptures of scale make sense.

The painting was purchased by a wealthy expatriate American writer-poet named Gertrude Stein and her brother, Leo Stein, who shared a home filled with modern art at 27 Rue de Fleurus, in Paris. This was also the location for Gertrude Stein’s weekly salon. Here, Matisse, Apollinaire, the young and largely unknown Picasso and other members of the avant-garde came together to exchange ideas.

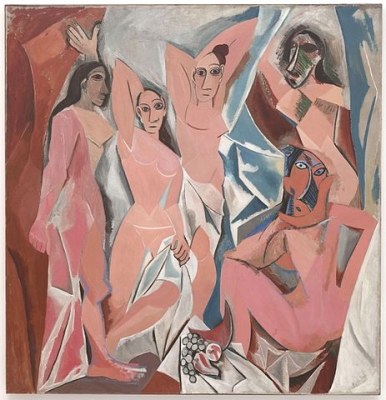

Stein was able to attract such a crowd not only because of her literary skills but because she often provided financial support to these nearly destitute artists. In fact, the Steins bought Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre soon after its completion and hung it in their dining room for all to see. One person who saw it there was Picasso. By all accounts the painting’s fame was too much for the terribly competitive young Spaniard. He determined to out do Matisse, and he did with his 1907 canvas, Demoiselles d’Avignon (MoMA).

Picasso turned Matisse’s sensuality into violent pornography. Matisse in turn responds to the challenge of what was then called “primitivism” with his own brand of aggression in his Blue Nude.

Additional resources:

This painting at The Barnes Foundation

The Fauves from the National Gallery of Art Online Tour

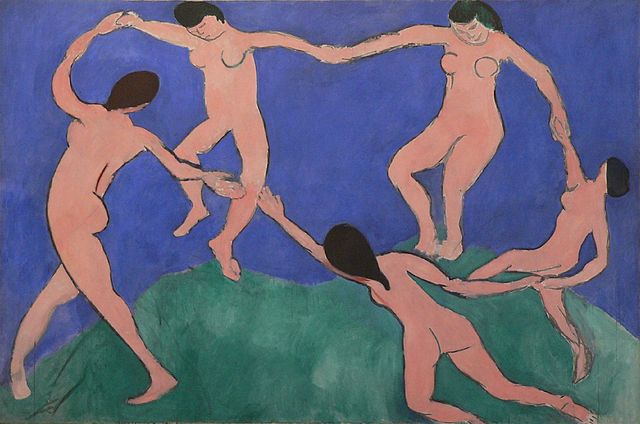

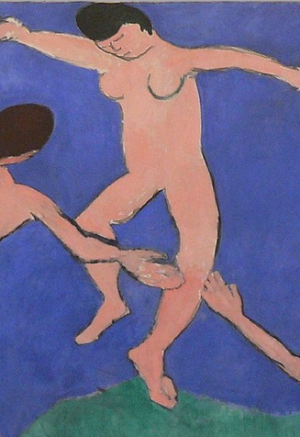

Henri Matisse, Dance I

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

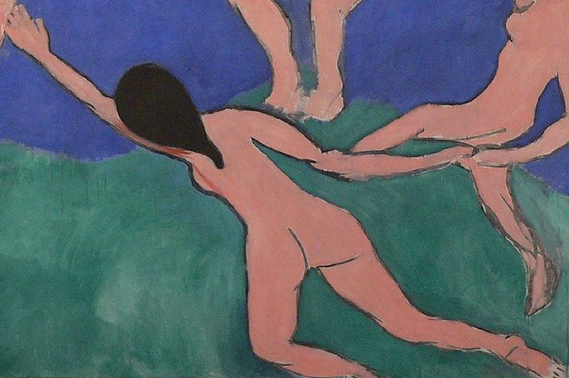

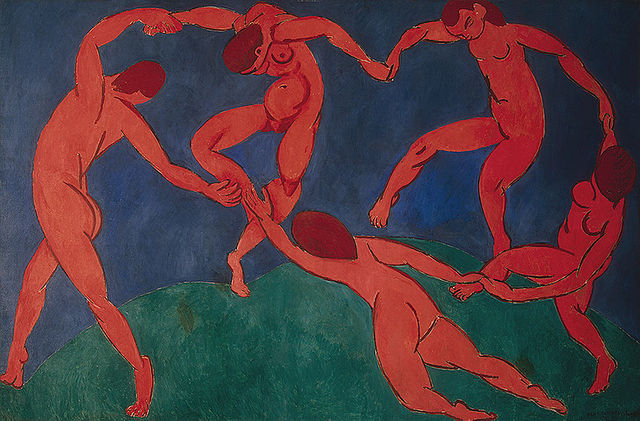

In 1909 Matisse received an important commission. An extremely wealthy Russian industrialist named Sergei Shchukin asked Matisse for three large scale canvases to decorate the spiral staircase of his mansion, the Trubetskoy Palace, in Moscow. The large and well loved painting, Dance I at MoMA, is somewhat disingenously titled. Although it is full scale and in oil, Matisse did not consider it more than a preparatory sketch. Yet a comparison between the initial and final versions is instructive. Matisse borrowed the motif from the back of the 1905-06 painting Bonheur de Vivre, although he has removed one dancer.

In Dance I, the figures express the light pleasure and joy that was so much a part of the earlier Fauve masterpiece. The figures are drawn loosely, with almost no interior definition. They have been likened to bean bag dolls because of their formless and unrestricted movements. The bodies certainly don’t seem to be restrained by way. But don’t let this childlike spontaneity fool you. Matisse works very hard to make his paintings seem effortless. Imagine for a moment, that instead of this childlike style, Matisse had decided to render this figures with the frozen density of Jacques Louis David. Would the sense of pure joy, the sense of play have been as well expressed? Matisse has done something that is actually very difficult. He has unlearned the lessons of representation so that he can create an image where form matches content.

The dancers inhabit a brilliant blue and green field. But what exactly does the green represent? Many people would quickly reply, “a grassy hilltop.” Okay, but what then is the blue intended to represent? If I were lecturing at MoMA, as I often do, many listeners would offer that “the blue is the sky that rises above the hill.” But others in my group might begin to look frustrated. One might then say, “that’s not what I see, the blue is really water moving back into the distance.”

What Matisse has done here, even in seemingly simple rendering, is use spatial ambiguity to explore one of the key issues in modern painting, the conflict between the illusion of depth and an acknowledgment of the flatness of the canvas. One final point here, did you notice the break in the circle? The hands of the two front dancers are parted. Matisse has been careful to allow this break only where it overlaps the knee so as not to interrupt the continuity of the color. Why do this? The part is often interpreted in two ways, as a source of tension that requires resolution or, as an invitation to us the viewer to join in, after all, the break is at the point closest to our position.

The final version of Dance has a very different emotional character. It has been described as forbidding, menacing, tribal, ritualistic, even demonic. Drum beats almost seem to be heard as the simple pleasure of the original is overwhelmed. What causes these dramatic changes in mood? Beyond the color shift, which is pretty obvious, the figures of the 1910 canvas are drawn with more interior line, line which often suggests tension and physical power. See for instance, the back left figure. Another more subtle change occurs where the two back figures touch the ground. In the 1909 canvas, the green reaches up to the feet of the two back most dancers, in the 1910 canvas, something else happens, the green seems to compress under the dancer’s weight. This subtle change creates either a sense of lightness or a sense of weight and contributes to the way we perceive each painting. So be careful before concluding that Matisse was actually drawing like a child, he knew exactly what he was doing.

Additional resources:

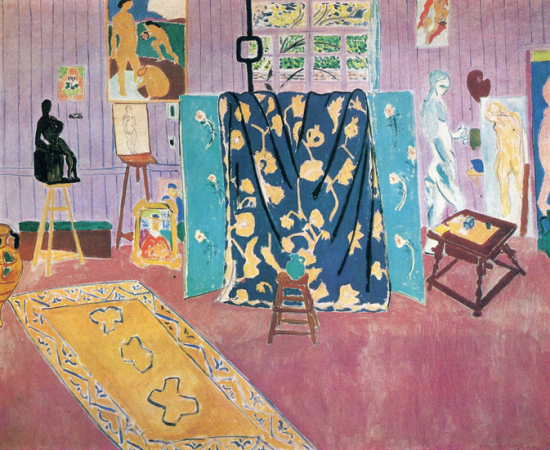

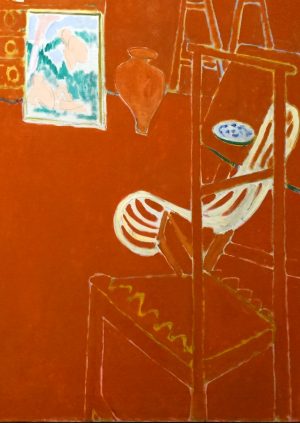

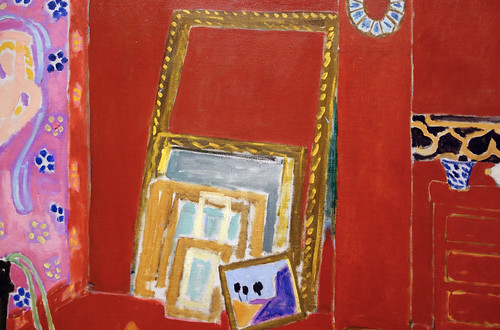

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Henri Matisse, The Red Studio, 1911, oil on canvas, 181 x 219.1 cm (Museum of Modern Art, New York). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Dismantling spatial illusion

Since Manet (and Degas, Monet, and Cezanne), artists have sought to undermine the illusion of space that had ruled painting since about 1425. Spatial illusion was increasingly seen as a defect that reduced the integrity of painting. But as the earlier painters of the avant-garde have shown, ridding a painting of illusion is almost impossible. The audience is trained to expect three dimensional space and sees it given the opportunity. This is Matisse’s challenge. He meets this challenge–the destruction of spatial illusion, in three stages.

The color red

Red is often thought of as the most aggressive color. It has the most punch, and that’s what Matisse needed here. This canvas was a part of a series, there is, for instance, a Pink Studio too. But that canvas was concerned with different issues. Here, the red is an attempt to find a color that is forceful enough to resist the illusion of deep space by pushing to the surface. The red is, of course painted onto the flat canvas but actually fails to remain there visually. Instead, the red becomes the walls and furnishing of the room seen in space. Illusion triumphs–Matisse is thwarted.

Illusionism

This triumph of illusion is due in part to the linear perspective that defines the table, chairs, and the walls and floor of the studio. But look! Matisse has constructed some of the worst linear perspective ever seen. Receding lines should converge, but look at the chair on the lower right. The lines widen as they go back. And look to rear left corner of the room. The corner is defined by the edge of the pink canvas but above that painting, the line that must define the corner is missing! Matisse is literally dismantling the perspective of the room but it makes no difference, we still see the room as an inhabitable space. Illusion still triumphs.

Figure-Ground Relationship

Although it is very difficult to see in reproduction, if seen in person at MoMA, it is clear that the whitish lines that define form in the red field are not painted on top of the red. Instead, they are reserve lines. In other words, the white lines are actually the canvas below. Matisse painted the red planes up to the line on either side, leaving a narrow gap of white canvas in between. This is really IMPORTANT. Stay with me on this. The white line is actually emerging from below the red. It is beneath. The red is of course painted on top of the white canvas.

Okay, now pay attention. Matisse has realized that illusion is almost certain to triumph no matter how aggressively he tries to undermine it. We, as the audience, will see space if given the slightest opportunity. So if we see illusion at such a basic level, what hope does Matisse have of destroying it? In fact, his reserve line are his really brilliant solution. The chairs, the dresser, the clock, each object, or figure in The Red Studio is constructed out of the canvas below. At the same time, the ground which supports those figures, is constructed out of a plane of red that is physically above the canvas. What Matisse has done then is reverse the figure ground relationship. He has made the figure out of the ground (the canvas) and made the ground out of the figure (the red paint on top). When seen in person, the recognition of this does finally destroy illusion, Matisse triumphs!

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Henri Matisse, The Blue Window

by THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Video from The Museum of Modern Art.

Additional resources:

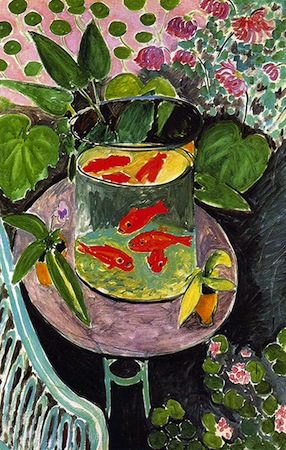

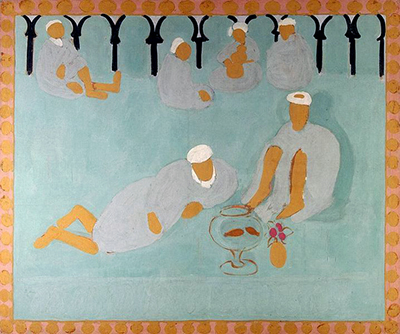

Henri Matisse, Goldfish

Goldfish were introduced to Europe from East Asia in the 17th century. From around 1912, goldfish became a recurring subject in the work of Henri Matisse. They appear in no less than nine of his paintings, as well as in his drawings and prints. Goldfish, 1912 belongs to a series that Matisse produced between spring and early summer 1912. However, unlike the others, the focus here centers on the fish themselves.

Color

The goldfish immediately attract our attention due to their color. The bright orange strongly contrasts with the more subtle pinks and greens that surround the fish bowl and the blue-green background. Blue and orange, as well as green and red, are complementary colors and, when placed next to one another, appear even brighter. This technique was used extensively by the Fauves, and is particularly striking in Matisse’s earlier canvas Le Bonheur de vivre. Although he subsequently softened his palette, the bold orange is reminiscent of Matisse’s fauvist years, which continued to influence his use of color throughout his career.

Golden age

But why was Henri Matisse so interested in goldfish? One clue may be found in his visit to Tangier, Morocco, where he stayed from the end of January until April 1912. He noted how the local population would day-dream for hours, gazing into goldfish bowls. Matisse would subsequently depict this in The Arab Café, a painting he completed during his second trip to Morocco, a few months later.

In a view consistent with other Europeans who visited North Africa, Matisse admired the Moroccans’ lifestyle, which appeared to him to be relaxed and contemplative. For Matisse, the goldfish came to symbolize this tranquil state of mind and, at the same time, became evocative of a paradise lost, a subject—unlike goldfish—frequently represented in art. Matisse was referring back to artists such as Nicolas Poussin (for example, Et in Arcadia ego), and Paul Gauguin (who painted during his travels to places like Tahiti).

The paradise theme is also prevalent in Matisse’s work. It found expression in Le Bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life), and the goldfish should be understood as a kind of shorthand for paradise in Matisse’s painting. The mere name “gold-fish” defines these creatures as ideal inhabitants of an idyllic golden age, which it is fair to say Matisse was seeking when he travelled to North Africa. It is also likely that Matisse, who by 1912 was already familiar with the art of Islamic cultures, was interested in the meaning of gardens, water and vegetation in Islamic art—as well as symbolizing the beauty of divine creation, these were evocations of paradise.

Metaphor for the studio

However, Goldfish was not painted in Morocco. Henri Matisse painted it at home, in Issy-les-Moulineaux, near Paris. Matisse had moved to Issy in September 1909 to escape the pressures of Parisian life. So what you see here are Matisse’s own plants, his own garden furniture, and his own fish tank. The artist was drawn to the tank’s tall cylindrical shape, as this enabled him to create a succession of rounded contours with the top and bottom of the tank, the surface of the water and the table. Matisse also found the goldfish themselves visually appealing. Matisse painted Goldfish in his garden conservatory, where, like the goldfish, he was surrounded by glass.

Contemplation

Matisse distinguished predatory observation from disinterested contemplation, the latter being his preferred approach. Goldfish invites the viewer to indulge in the pleasure of watching the graceful movement and bright colors of the fish. Matisse once wrote that he dreamt of “an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art that could be […] a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.” This is precisely what Matisse wanted Goldfish to provide for the viewer.

Constructing pictorial space

The painting contains a tension created by Matisse’s depiction of space. The fish are seen simultaneously from two different angles. From the front, the goldfish are portrayed in such a way that the details of their fins, eyes and mouths are immediately recognizable to the viewer. Seen from above, however, the goldfish are merely suggested by colorful brushstrokes. If we then look at the plants through the transparent glass surface, we notice that they are distorted compared to the ‘real’ plants in the background.

Matisse paints the plants and flowers in a decorative manner. The upper section of the picture, above the fish tank, resembles a patterned wallpaper composed of flattened shapes and colors. What is more, the table-top is tilted upwards, flattening it and making it difficult for us to imagine how the goldfish and flowerpots actually manage to remain on the table. Matisse constructed this original juxtaposition of viewpoints and spatial ambiguity by observing Paul Cézanne’s still-life paintings. Cézanne described art as “a harmony parallel to nature”. And it is clear here that although Matisse was attentive to nature, he did not imitate it but used his image of it to reassemble his own pictorial reality. Although this can be confusing for the viewer, Matisse’s masterful use of color and pattern successfully holds everything together.

This painting is an illustration of some of the major themes in Matisse’s painting: his use of complimentary colors, his quest for an idyllic paradise, his appeal for contemplative relaxation for the viewer and his complex construction of pictorial space.

Additional Resources:

Matisse’s Goldfish and Sculpture, MoMA

Matisse’s Young Woman before an Aquarium, Barnes Foundation

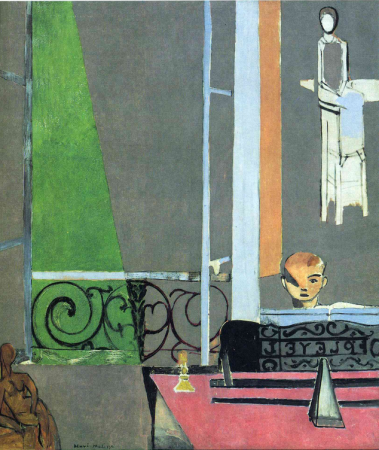

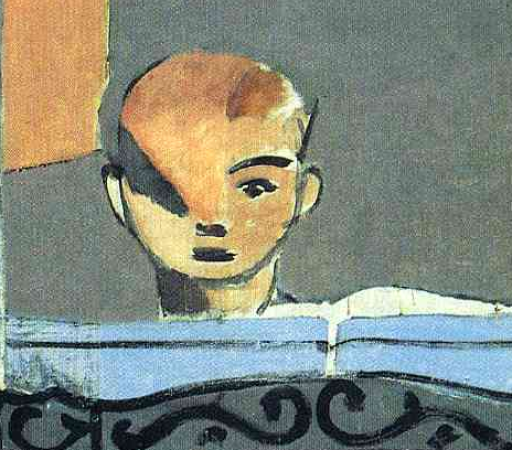

Henri Matisse, The Piano Lesson

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Henri Matisse, The Piano Lesson, 1916 (MoMA)

Key points:

- With its austere geometries and structured sense of balance, The Piano Lesson is sometimes seen as Matisse’s answer to Cubism.

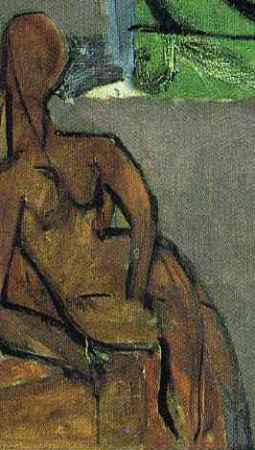

- The composition opposes the sensual, suggested by the sculpture in the left foreground, to discipline and order, implied by the geometric image of a woman in the upper right.

- This painting could serve as an allegory on art making, which requires balance between emotional expression and intellectual understanding.

This highly abstract painting is important because of its relation to the Cubist grid developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, because of its biographical aspects, and especially due to its thoughtful iconography (symbolic content).

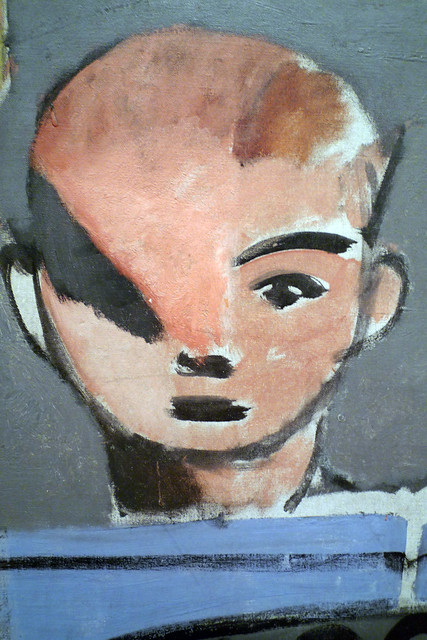

A nostalgic image

This large flat gray painting can be a bit confusing at first. Let’s begin with the boy in the lower right. He is the artist’s son, Pierre Matisse, who grows up to become a famous art dealer in New York in the 1940s. It’s worth remembering that 1916 was during world war one, the most devastating conflict Europe had yet known. When Henri painted this image, Pierre was actually mobilized. The painter did not know if his son would return. In a way then, this is a nostalgic image, Matisse has painted his son much younger then he actually was, perhaps recalling happier times. Maybe happy isn’t really the right word since Pierre looks pretty miserable. Maybe I’m just remembering my own childhood piano lessons, but his is a look of worried concentration. A portion of his face even seems to reflect that instrument of the devil, commonly known as a metronome. Pierre sits at the piano well off to the side, trapped in the house even as the open French window (a floor-to-ceiling hinged window that opens onto a wrought iron railing) beckons. Finally, what is that very abstract truncated triangle of green? Often it is interpreted as ray of sun reaching across the lawn outside.

You can see why poor little Pierre is so attentive. His music teacher literally hovers above him, cold, distant, and aloof. What a wonderful contrast to the other female figure in the painting.While the teacher represents discipline through her rigid rectilinear form, the small bronze nude at the lower left is virtually all curves. This small sculpture by Matisse is meant to represent the creative spirit while the teacher represents discipline, and like two boxers between rounds, each is in her corner. But wait! Is the teacher really there? Space is so ambiguous that it is hard to tell if there is really a distant room for her to inhabit. In fact, there is not and she is not. This is Matisse’s house in the suburb Issey-les-Moulineaux and this is a wall. The “teacher” is actually a painting by Matisse titled, Woman on a High Stool (Germaine Raynal), 1914 (MoMA).

Matisse has transformed the original painting in order that Raynal play the part of the strict instructor, Matisse often created variations on themes that he had already treated. So, in fact, Matisse has created a painting of a painting and a painting of a sculpture. This suggests that perhaps The Piano Lesson is not only about Pierre and his childhood experiences but more importantly, the act of creation itself. Is Pierre actually a stand in for Henri? After all, music is a common metaphor for the visual arts.

A visual equivalent of music

Is Matisse then saying that art is the result of both sensual creativity (the sculpture) and strict discipline (the painting)–is the metronome that swings between the two, a mediator? And then what of the odd inclusion of the carved music stand which contains the brand of the piano, “PLEYEL” (which is read backwards as we see it)?

As you can see from the later and less abstract painting Music Lesson, Matisse has removed everything that is not essential from the 1916 canvas. So why then retain these letters? And why retain the playful swirling wrought iron fence? According to Jack Flam, a leading Matisse scholar and an old instructor of mine (and by the way, not very strict nor rectilinear), Matisse wants us to read the letters from right to left and then continue to read past the music stand by jumping to the curving iron fence which he believes to be an abstract expression or visual equivalent of the music (art) that is being produced.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Henri Matisse, the illustrated book Jazz

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Expressionism

The term "Expressionism" first emerged as a way to classify new types of art that emphasized emotional impact over descriptive accuracy.

c. 1905 - 1914

Expressionism, an introduction

by SHAWN ROGGENKAMP

Imagine a painting where the magentas scream, the greens glare, and coarse brushstrokes become more ominous the longer you look at them. Paintings like this, where the artist uses color, line, and visible techniques to evoke powerful responses from the viewer date from the early twentieth century but continue expressive traditions that can be found throughout art’s history (see, for example, work by Francisco Goya). When capitalized as “Expressionism,” however, the term refers more specifically to an artistic tendency that became popular throughout Europe in the early twentieth century. Like many categories in art history, Expressionism was not a name coined by artists themselves. It first emerged around 1910 as a way to classify art that shared common stylistic traits and seemed to emphasize emotional impact over descriptive accuracy. For this reason, artists like Edvard Munch straddle the line between Post-Impressionist developments in late 19th century painting and early 20th century Expressionism. Likewise, the Fauves in France exhibited similar characteristics in their work and are often linked to Expressionism.

Expressionism in Germany

Though many artists of the early twentieth century can accurately be called Expressionists, two groups that developed in Germany, Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), are among the best known and help to define the style. Influenced in part by the spiritual interests of Romanticism and Symbolism, these artists moved further from the idealized figures and smooth surface of 19th century academic painting that can be seen in paintings by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, for example. Instead of depicting the visible exterior of their subjects, they sought to express profound emotional experience through their art. German Expressionists, like other European artists of the time, found inspiration in so-called “primitive” sources that included African art, as well as European medieval and folk art and others untrained in Western artistic traditions. For the Expressionists, these sources offered alternatives to established conventions of European art and suggested a more authentic creative impulse.

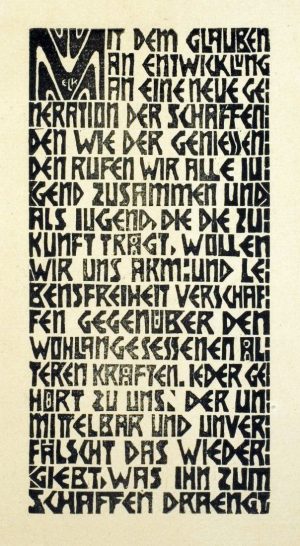

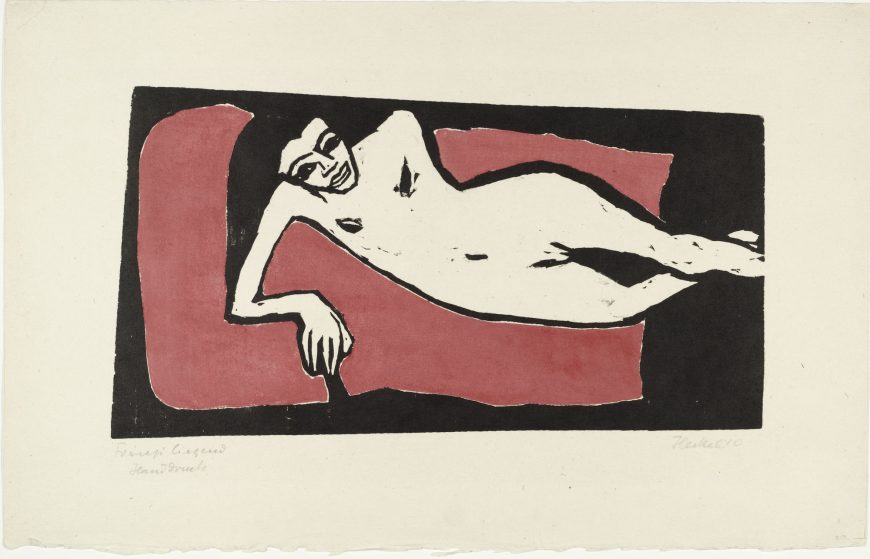

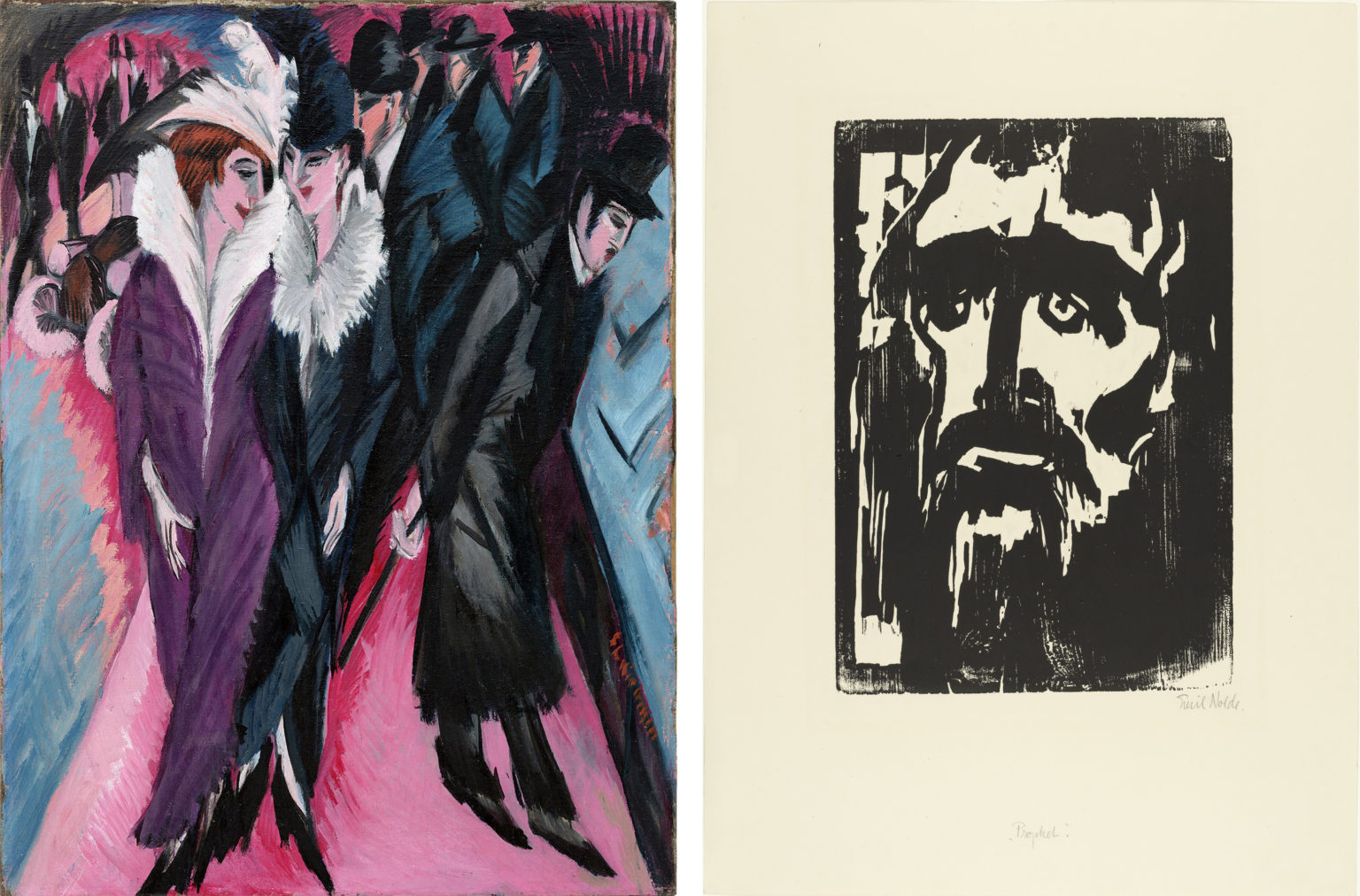

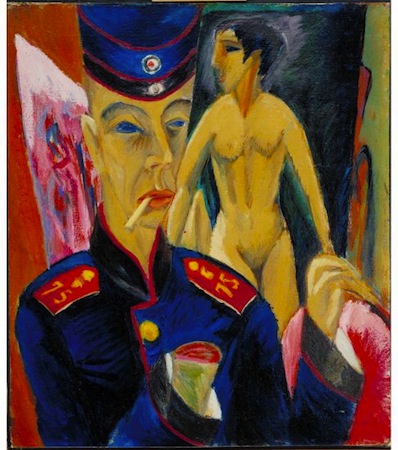

Die Brücke

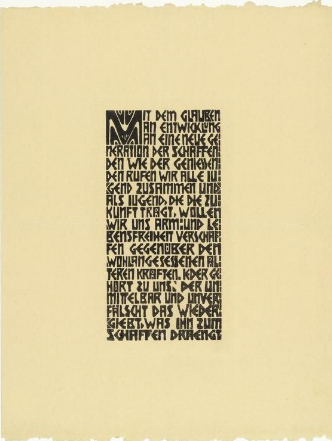

In 1905, four young artists working in Dresden and Berlin, joined together, calling themselves Die Brücke (The Bridge). Led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, the group wanted to create a radical art that could speak to modern audiences, which they characterized as young, vital, and urban. Drawn from the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, the nineteenth-century German philosopher, the name “Die Brücke” describes their desire to serve as a bridge from the present to the future. While each artist had his own personal style, Die Brücke art is characterized by bright, often arbitrary colors and a “primitive” aesthetic, inspired by both African and European medieval art. Their work often addressed modern urban themes of alienation and anxiety, and sexually charged themes in their depictions of the female nude.

Their first exhibition was held in the showroom of a lamp factory in Dresden in 1906 for which they published a program of woodcut prints reflecting their interest in earlier traditions of German art. In the introductory broadsheet (above left), Kirchner made clear the group’s revolutionary intentions. He proclaimed,

With faith in progress and in a new generation of creators and spectators we call together all youth. As youth, we carry the future and want to create for ourselves freedom of life and of movement against the long established older forces.\(^{1}\)

This optimism was not long-lived. Internal squabbling caused the group to dissolve in 1913 just prior to the start of the First World War.

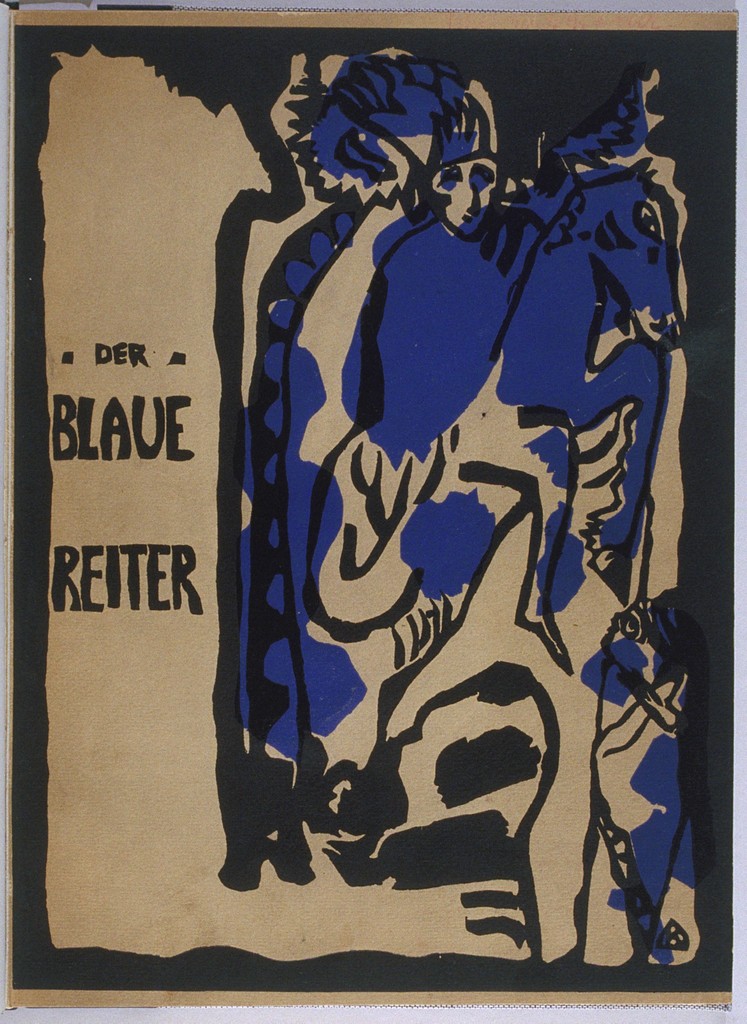

Der Blaue Reiter

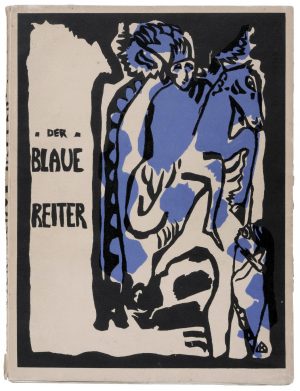

Based in the German city of Munich, the group known as Der Blaue Reiter lasted only from their first exhibition at the Galerie Thannhausen in 1911 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Created as an alternative to Kandinsky’s previous group, the more conservative Neuen Künstlervereinigung München (New Artists Association of Munich or NKVM), Die Blaue Reiter took its name from the motif of a horse and rider, often used by founding member Vasily Kandinsky.

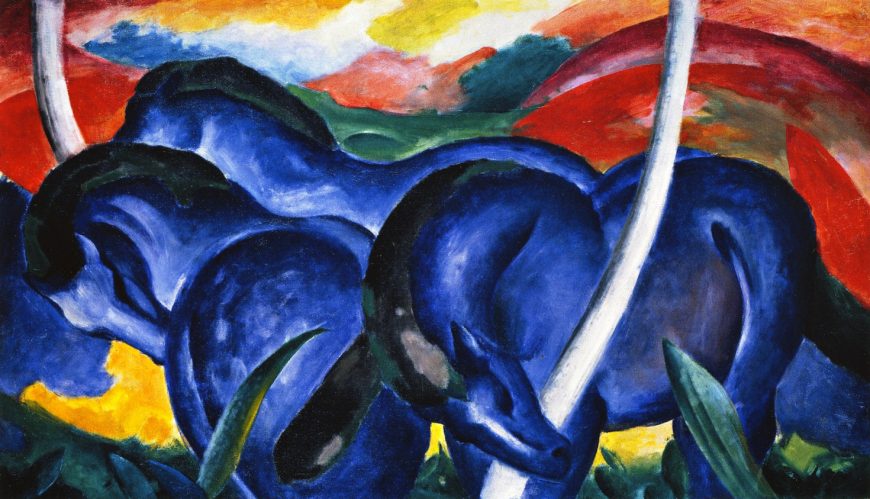

This motif appeared on the cover of the Blue Rider Almanac (left), published in May 1912, and reflects Kandinsky’s interest in medieval traditions and the folk art of his Russian homeland. In contrast to Die Brücke, whose subjects were physical and direct, Kandinsky and other Die Blaue Reiter artists explored the spiritual in their art, which often included symbolism and allusions to ethereal concerns. They thought these ideas could be communicated directly through formal elements of color and line, that, like music, could evoke an emotional response in the viewer. Conceived by Kandinsky and Franz Marc, the almanac included essays by themselves and other German and Russian artists, musical compositions by Expressionist composers, such as Arnold Schönberg, and Kandinsky’s experimental theater piece, “Der gelbe Klang” (The Yellow Sound). This range of content shows Der Blaue Reiter’s efforts to provide a philosophical approach not just for the visual arts, but for culture more broadly. These ideas would become more fully developed at the Bauhaus where Kandinsky taught after the war (Marc died during the Battle of Verdun in 1916).

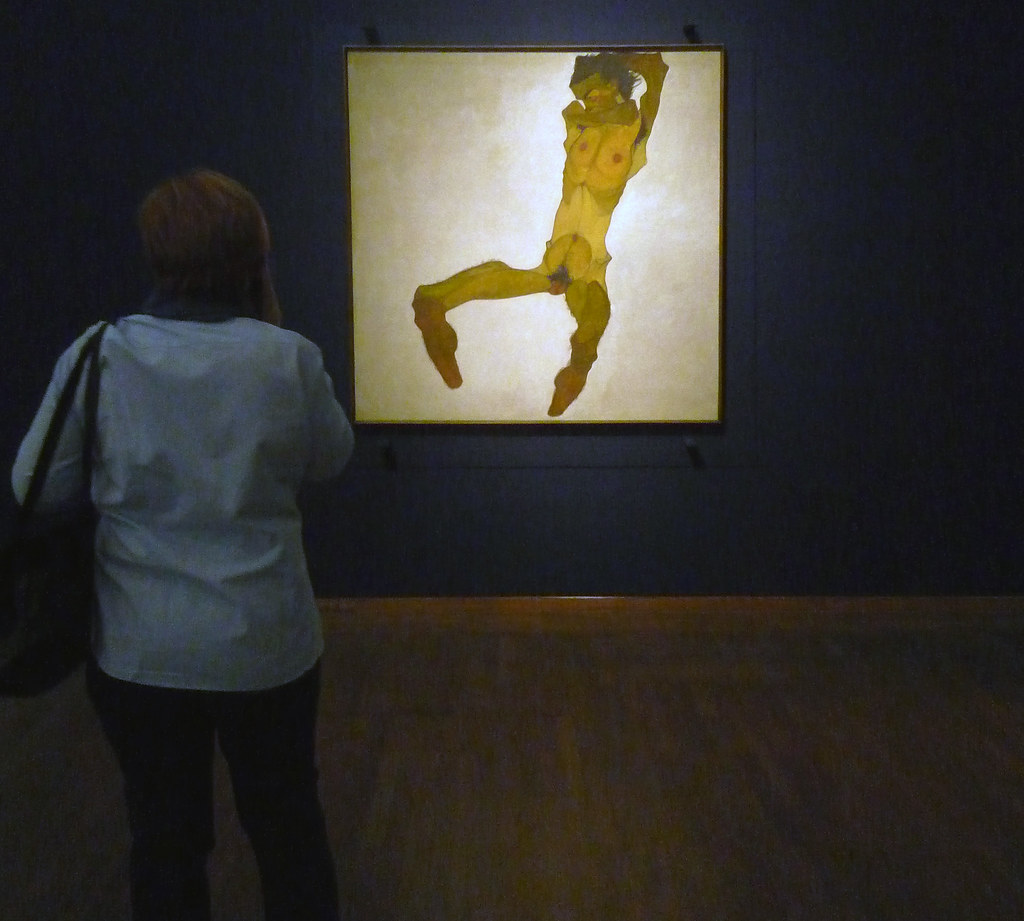

Austrian Expressionism

While the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups had relatively defined memberships, Expressionist artists also worked independently. In Vienna, Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele stand out for paintings that show intense, often violent feeling and for their efforts to represent deeper psychological meaning.

In the aftermath of the First World War, many artists in Germany felt that the forceful emotional style of Expressionism that had been so progressive before the war but had become less appropriate. Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) arose as a direct response to pre-war stylistic excess.

\(^{1}\)Translated excerpt from Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1993, page 65

Additional resources

Artists of Brücke: Themes in German Expressionist Prints (MoMA)

Der Blaue Reiter Almanac (MoMA)

Brücke Museum, Berlin (in German)

Fauvism on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Expressionism as Nordic?

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

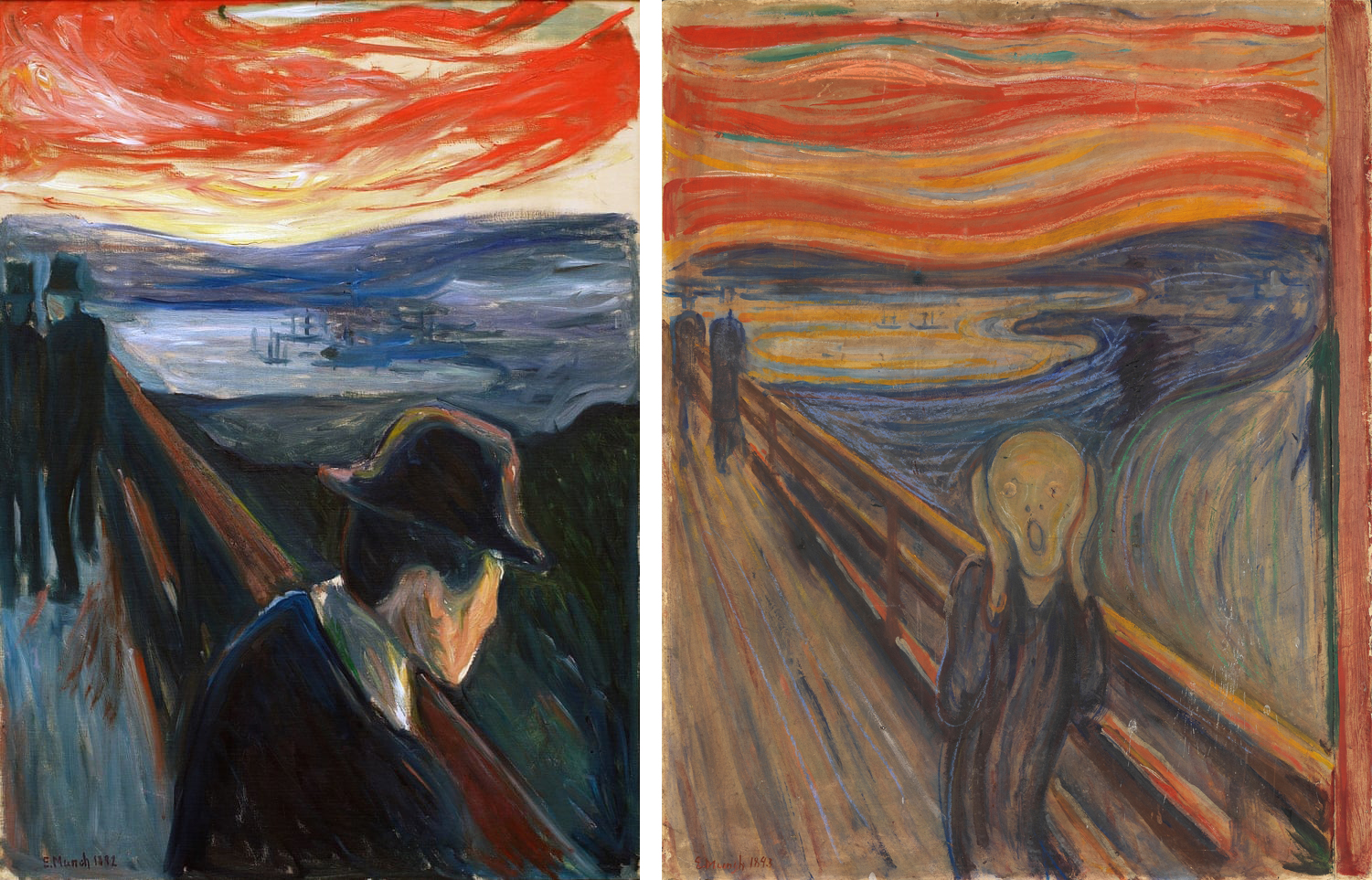

Edvard Munch’s The Scream is recognized from Toledo to Timbuktu as a powerful visual expression of anxiety, but it had its genesis in a very specific place. As the artist recollected in a diary entry of 22 January 1892:

I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun went down – I felt a gust of melancholy – suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, tired to death – as the flaming skies hung like blood and sword over the blue-black fjord and the city – My friends went on – I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I felt a vast infinite scream [tear] through nature.\(^{[1]}\)

Munch was deeply affected by this incident and depicted it several times: first as Despair in 1892, and then in several different versions in different media under the title The Scream.

Munch’s moment of anxiety occurred on a road along Ekeberg Hill overlooking Oslo. The wooden railing visible in the paintings and mentioned in his diary lined the steep cliffside of the fjord protecting Oslo’s port. There is even some evidence that the famous blood-red, undulating sky that Munch associated with this feeling may also have been geographically specific. It closely resembles the pattern formed by polar stratospheric clouds visible almost exclusively in Northern Europe during the winter dusk.

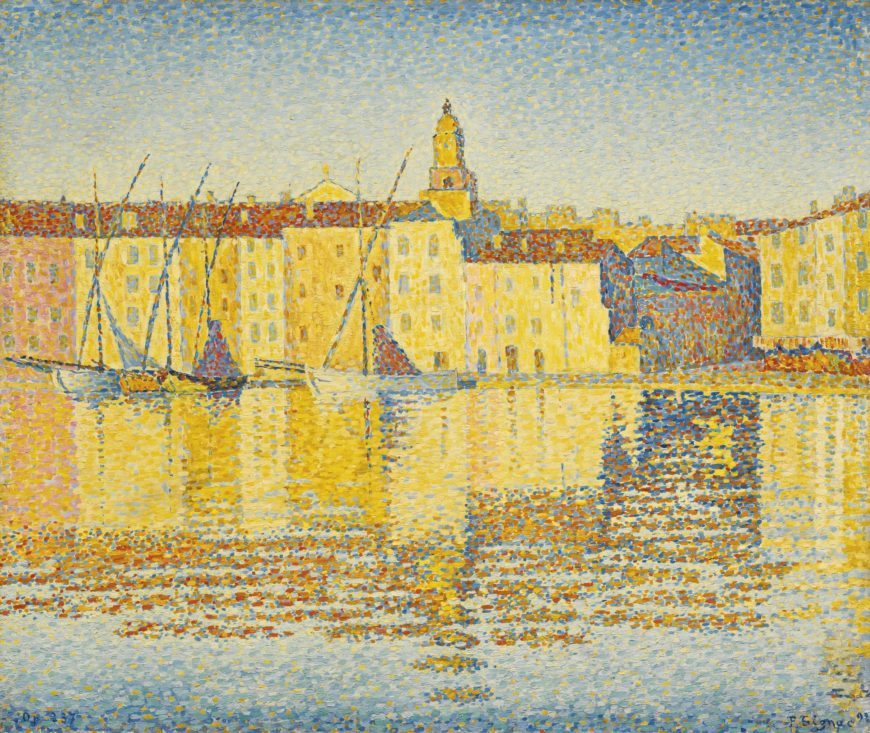

Munch’s vivid diary entry occurred in a very different location, however: Nice, in the south of France, where the artist was vacationing at the time. Even the relative warmth and bright sunshine of the French Mediterranean, evoked in this contemporary painting of Saint-Tropez by Neo-Impressionist artist Paul Signac, could not relieve Munch of the deep anxiety he remembered experiencing in the cold north.

Climatic determinism

This contrast between Norway and the south of France in terms of temperament as well as temperature illustrates what was once a commonplace of cultural geography: the idea that climate significantly shapes the psychological characteristics, not just of individuals, but of whole societies. Although this idea is currently discredited by its association with racist pseudo-science, it had widespread currency during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was commonly believed that there was a major cultural divide in Europe between the sun-filled south, associated with temperate, Classical rationality, and the cold north, which was riddled with spiritual angst and melancholy.

Even today, Expressionist art is primarily associated with northern Europe. Many Scandinavian and German Expressionist artists took great pride in their Nordic or Teutonic heritage and attempted to define and revive a distinctly Northern European artistic tradition that was fundamentally different from Mediterranean Classicism.

Classical versus Gothic

One champion of this idea was the German art historian Wilhelm Worringer, whose book Form Problems in the Gothic (1910) provided an important theoretical framework for German Expressionism. For Worringer, the Gothic was more than just a late Medieval style. There was a “latent Gothic” in the art of the Germanic tribes (called Goths) that fought against Rome, running through the distinctively Northern versions of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and continuing into his own time. This tradition had, however, been overshadowed by Mediterranean Classicism, which had long been considered the aesthetic ideal. Northern Gothic art was seen as an incompetent attempt at naturalism, rather than a distinct tradition of its own.

Worringer described Mediterranean Classical art as rational, beautiful, joyful, and tranquil, while he saw the Northern Gothic tradition as more spiritual and as having greater “depth, grandeur, and power.”\(^{[2]}\) In a particularly vivid passage, Worringer contrasts the type of line preferred by each of these traditions. Classicism tends toward “beautiful, round, organically tempered curves” where the Gothic prefers a “stiff, angular, repeatedly interrupted, jagged line of [the] strongest expressive force.” This difference in style results from different temperaments of the Germanic versus Latin peoples:

As those line scrawls seem merely the release of an inner spiritual pressure, so the excitement, the convulsiveness, the fever, of northern drawing unquestionably throws a flashlight upon the heavily oppressed inner life of northern humanity.\(^{[3]}\)

For Worringer, artistic style reveals the inner, psychological state, not just of the individual artist, but of an entire culture.

Woodcut prints and Expressionism

According to Worringer, even Nordic artists who adopted some Italian Classical characteristics, such as the German Renaissance printmaker Albrecht Dürer, remain fundamentally Gothic in their approach. Dürer’s woodcut prints embody the jagged, angular linearity and flat space that is characteristic of Worringer’s Gothic.

The German Expressionists deliberately revived the technique of woodcut printing because of this relatively crude, expressive style, as well as its nationalistic association with great German artists such as Dürer. Like Worringer, the German Expressionists saw a jaggedly angular, flat style as an authentic expression of their national tradition.

Both of these prints, furthermore, radiate the spiritual angst that Worringer associated with Nordic psychology. Dürer’s shows the four horsemen of the Apocalypse wreaking havoc in the world, while Schmidt-Rottluff’s Christ confronts the viewer with a face swollen and misshapen by torment. On his forehead the year 1918 is emblazoned in order to connect Christ’s suffering with the contemporary state of the world, then enmeshed in the first World War.

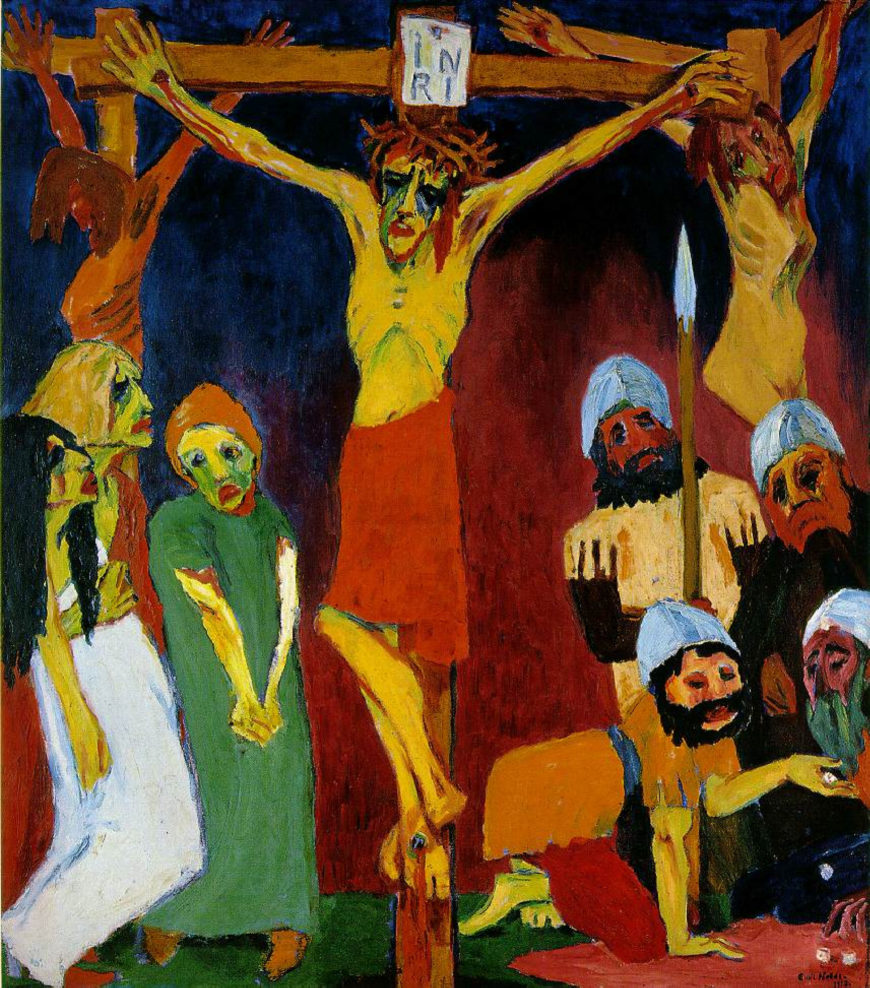

Emil Nolde and Expressionist nationalism

The German Expressionist Emil Nolde was particularly explicit in linking himself to a Nordic tradition. In his autobiography, Nolde wrote:

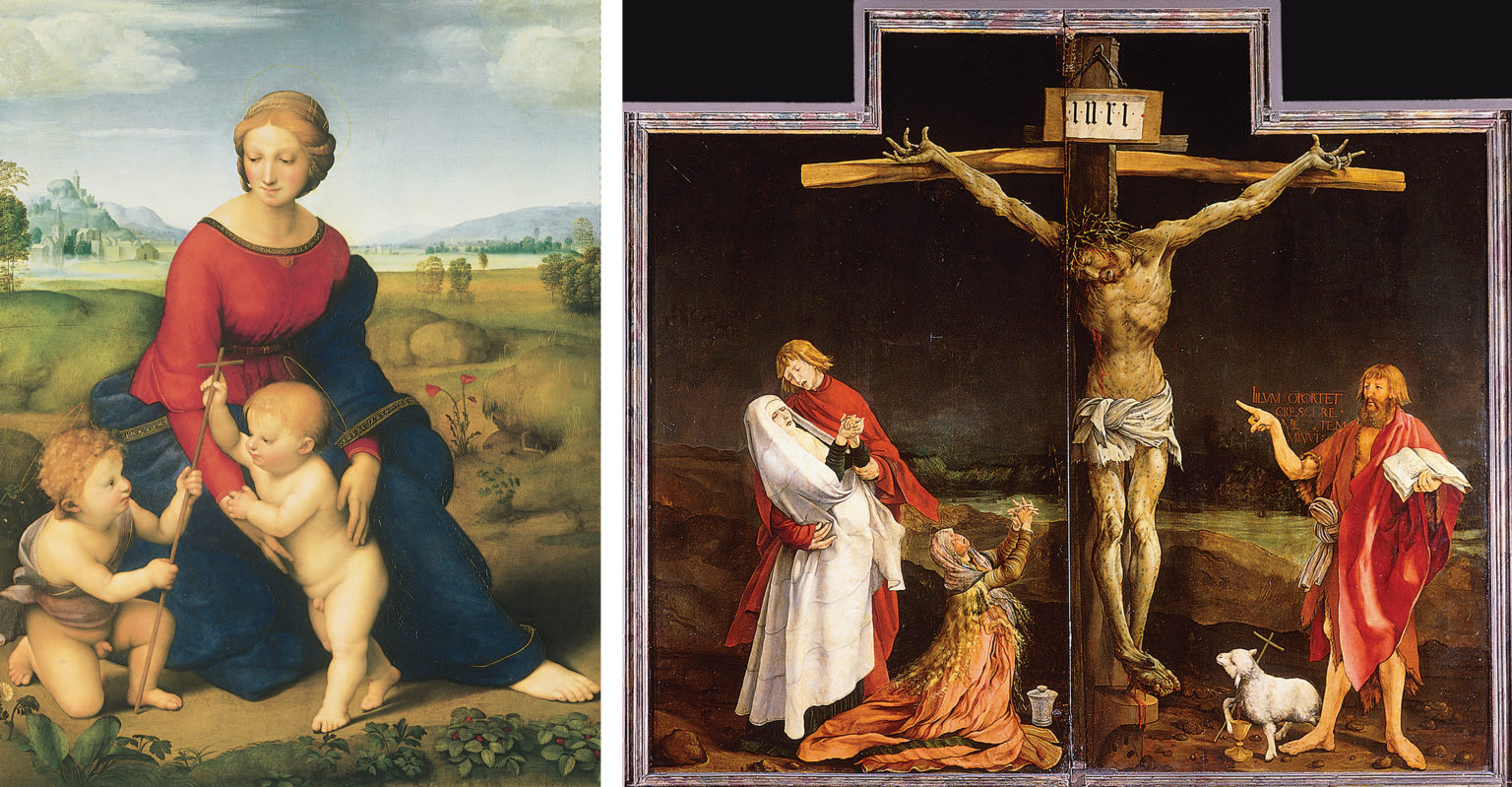

Glory be to our strong, healthy German art. [I much prefer] the holy German madonnas, invested with the soul of Grünewald and others, over the Latin, superficially presentable paintings of Raphael . . . All the arts of all the Mediterranean people share certain qualities . . . Our German art has glorious qualities of its own. We respect the art of the Latins; German art has our love. The Edda, the Isenheim Altar, Goethe’s Faust, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra . . . these proud, sublime works of Nordic Germanic peoples! These are eternal truths.\(^{[4]}\)

The psychological contrast that Nolde suggests between Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece and a Raphael Madonna could not be more pronounced. Not only is the latter, showing a Virgin and Child in a meadow, an inherently more tranquil subject than Grünewald’s harrowing Crucifixion, we can also recognize some of Worringer’s distinctions between Latin and Gothic forms. Raphael’s painting emphasizes deep space, soft curves, and idealization, whereas Grünewald’s altarpiece features flattened space, jagged, angular shapes, and dark, gruesome realism.

Coda: Expressionism and National Socialism

It is one of the great ironies of art history that the best-known propagandists of German nationalism, the Nazi party of the 1930s and 40s, supported Mediterranean Classicism rather than the Northern “Gothic” artistic tradition identified by Worringer and the Expressionists. Far from being celebrated as a native hero by the Nazis, Emil Nolde was issued a Malverbot (German for “forbidden to paint”), and 27 of his works were featured in the Degenerate Art exhibition that Hitler sponsored in 1937.

It should also be noted that these distinctions between “Mediterranean” and “Gothic” style depend upon a careful selection of examples, and that the extrapolation of those distinctions into temperamental, spiritual, or “racial” differences tends to be ideologically motivated. Regional differences can be identified in the history of art, but art historians today more commonly attribute them to conventional cultural traditions, rather than innate or climatologically-determined psychological or spiritual differences.

Notes:

- Edvard Munch, entry from the ‘Violet Diary,’ Nice, 22 January 1892, as translated by Ingeborg Owesen in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1815-1900 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), p. 1044.

- Wilhelm Worringer, Form Problems of the Gothic, unknown translator, (New York: G. E. Stechert, [1920]), pp. 43, 35.

- Ibid., pp. 49-50.

- Emil Nolde, Jahre der Kämpf (Berlin, 1934), as translated by Ernest Mundt in Herschel B. Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art (Berkeley, L.A. and London: University of California Press, 1968), p. 151.

Der Blaue Reiter

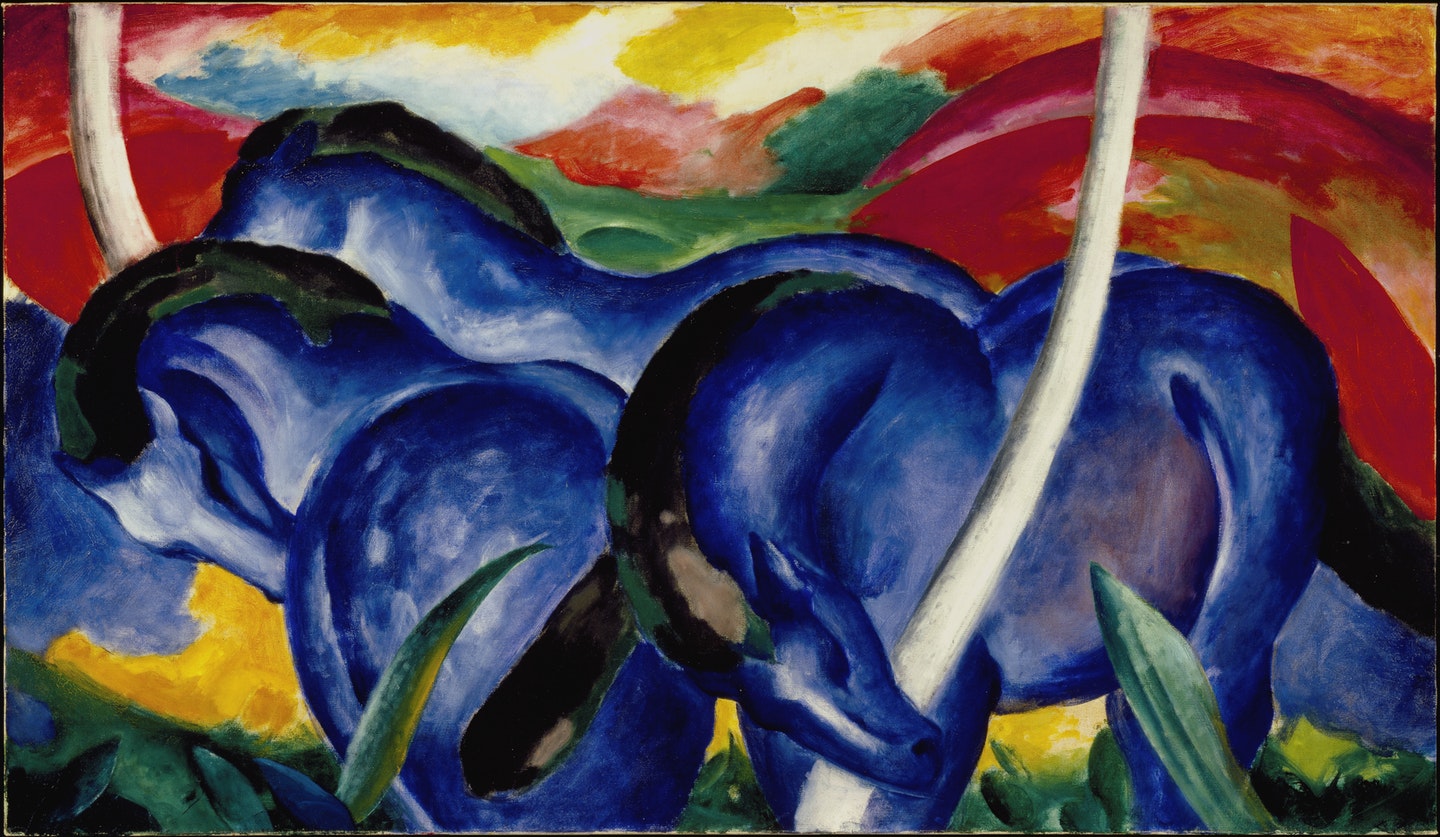

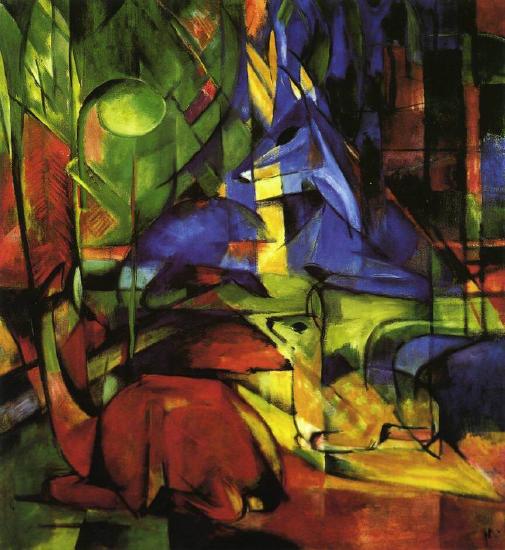

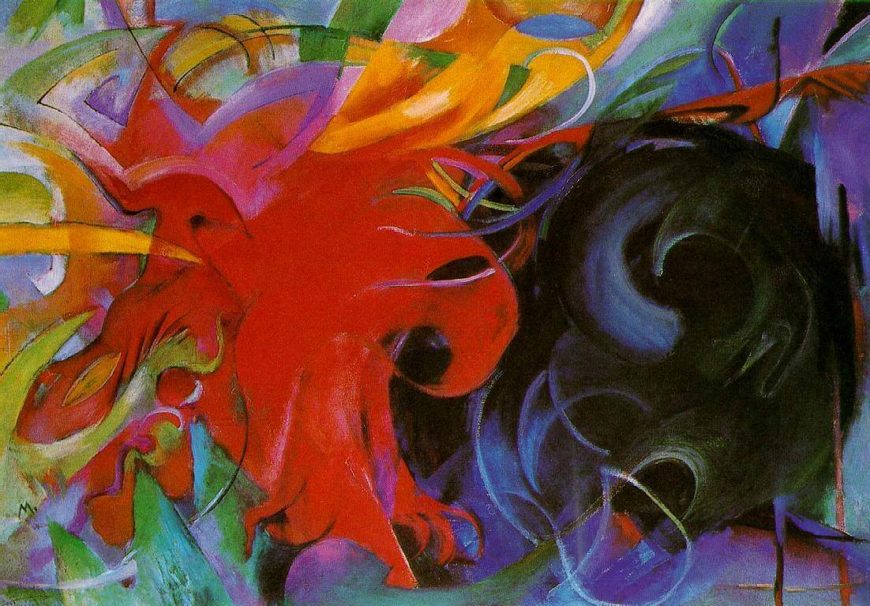

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

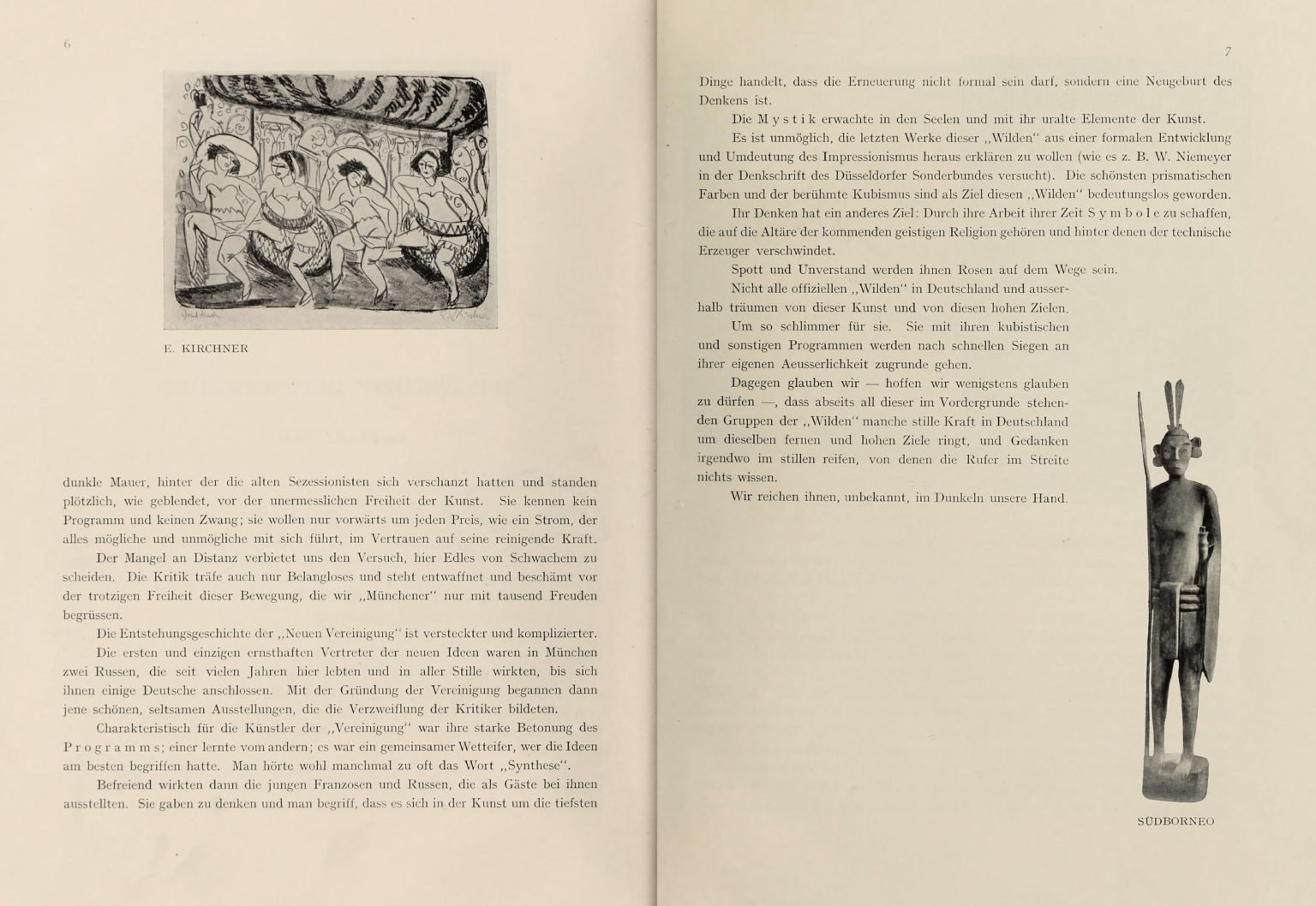

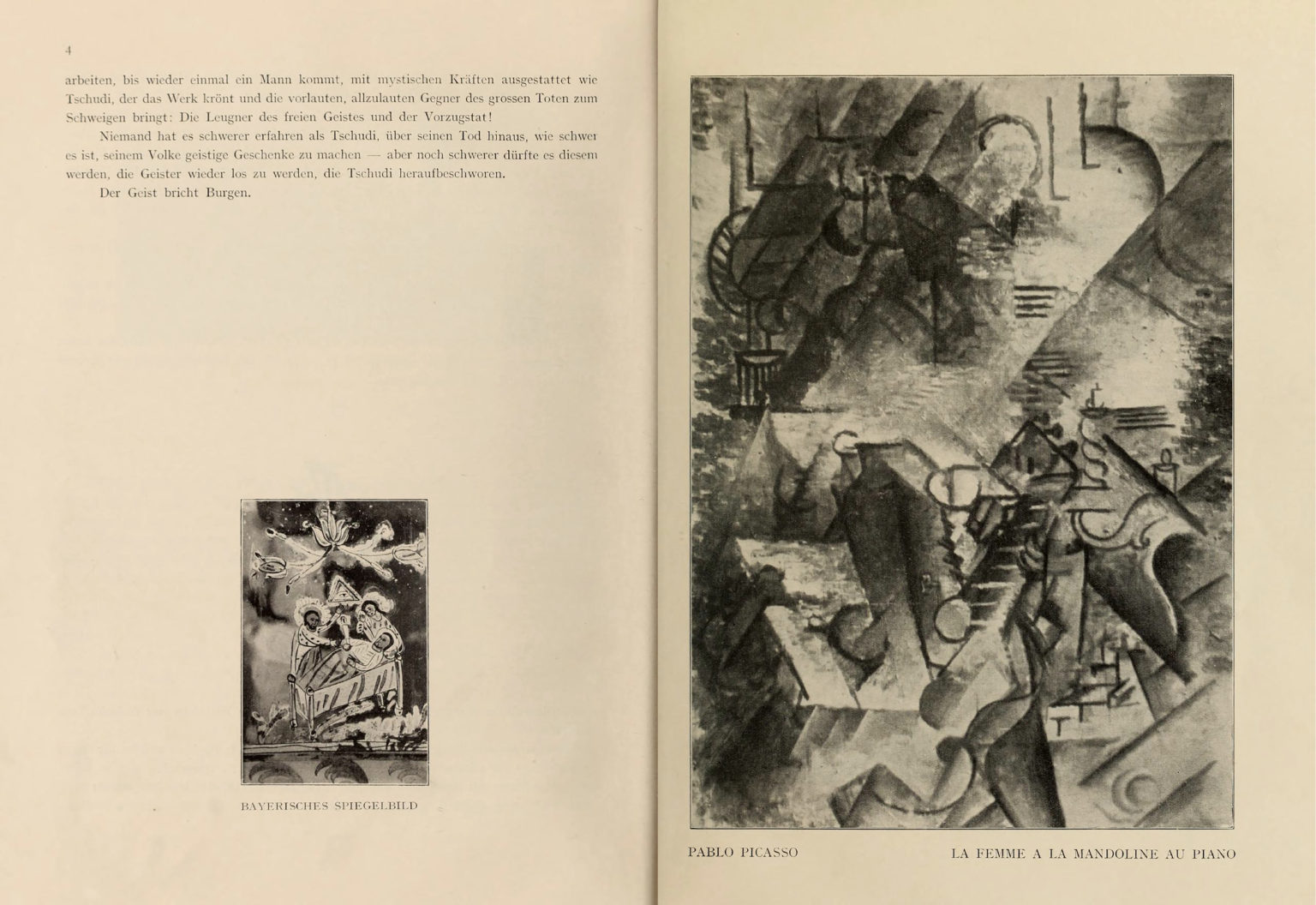

The 1912 art book Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) was originally intended to be a yearly “almanac” published by a Munich-based artists’ collective of the same name. It is a fascinating document of the early-twentieth century Expressionist art scene, featuring a dozen essays on topics ranging from so-called primitive masks to the stage direction for an experimental “color-tone drama” called The Yellow Sound. Particularly interesting is the eclectic variety of its illustrations, which combine the work of modern artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso with African statues, Chinese ink painting, German folk art, Renaissance woodcuts, and Medieval sculpture.

An inner Renaissance

One of the editors of the book, the Russian artist Vasily Kandinsky, wrote of Der Blaue Reiter’s intent, “We aim to show by means of the variety of forms represented how the inner wishes of the artist are embodied.”\(^{[1]}\) This emphasis on the “inner” or subjective mental states of the artist, as opposed to the “outer” or objective experience of nature, is a central theme of Expressionist art theory.

In a preface to the group’s first exhibition, Kandinsky similarly detects in his fellow artists “the signs of a new inner Renaissance.”\(^{[2]}\) The word “inner” distinguishes this new Renaissance from the Italian Renaissance of the 1400s, which saw the rise of a naturalistic style of representation that, many Expressionist artists contended, was only concerned with representing the outer appearances of material reality. The crude, almost childlike simplicity of the cover art for the Almanac, along with its Christian medieval imagery of the blue rider as Saint George, is a visual emblem of two of the groups’ main themes that will be explored here: primitivism and spirituality.

An artists’ collective

The members of the Blaue Reiter group, including Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc, Auguste Macke, Vasily Kandinsky, and Alexej von Jawlensky, banded together because they felt that the art establishment had shut them out of opportunities. In the modern period, like-minded artists would often form such cooperatives to sponsor their own exhibitions free from conservative art juries, as well as to provide for mutual support and the exchange of ideas. Among the art movements that got their start in this way were the Impressionists, the Vienna Secession, the Fauves, and another German Expressionist group, Die Brücke.

The name Der Blaue Reiter, as Kandinsky later somewhat flippantly suggested, was chosen because fellow artist Franz Marc liked horses and Kandinsky liked riders, and they both liked the color blue. The group’s emblem was the Roman Christian soldier Saint George, who slew a dragon that was demanding human sacrifices.

The figure of the Blue Rider thus embodied the spiritual focus of the group as well as their belief that art plays an important social role in the struggle between good and evil. The intensified color and simple, almost childlike rendering of the same story by Auguste Macke is characteristic of the group’s style, although as Kandinsky noted above, they recognized the great variety of ways in which “inner” states could be expressed.

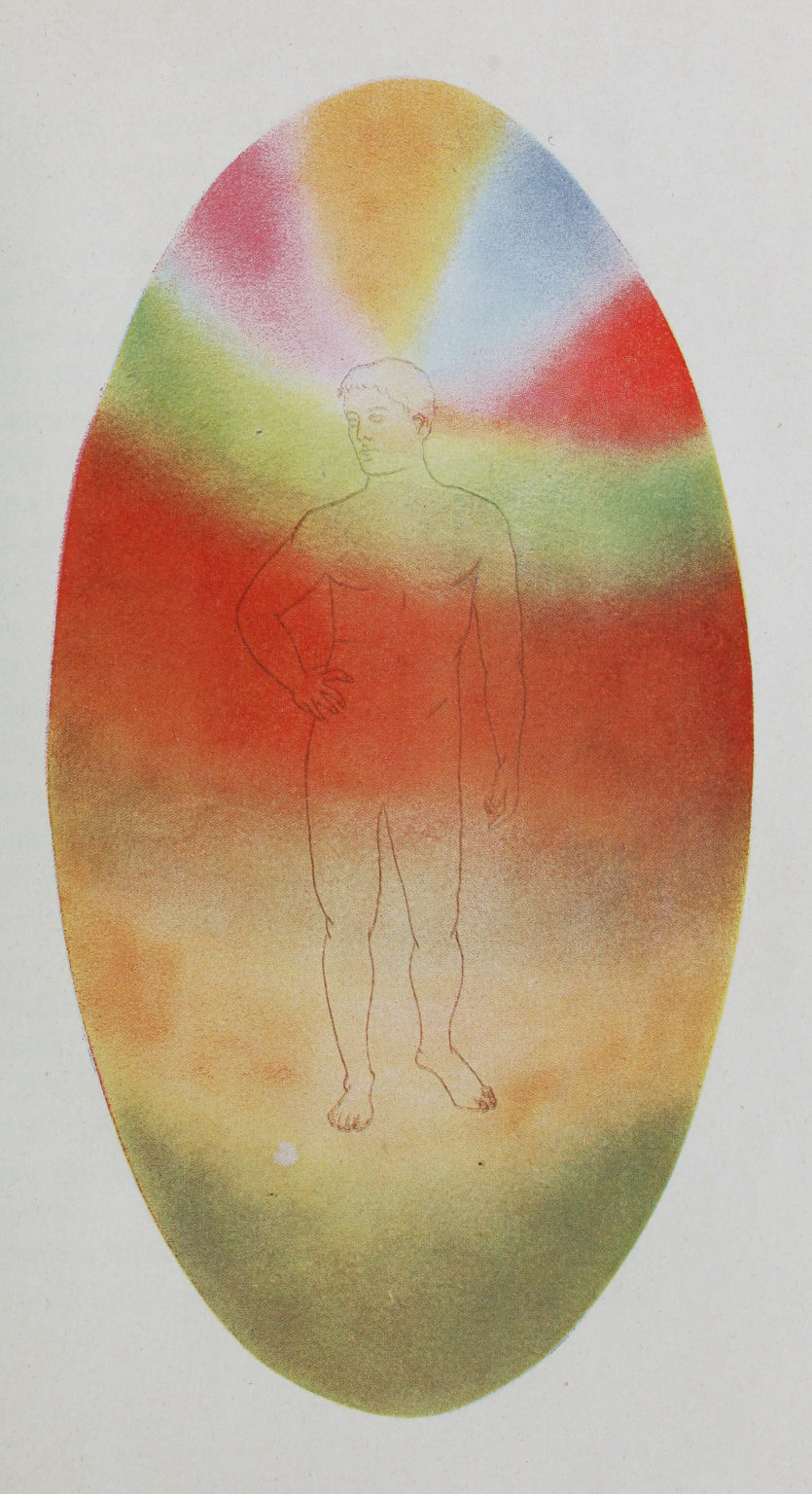

Primitivism and spirituality

In addition to work by its members, the Almanac and the group’s exhibitions featured works by Medieval, non-European, and untrained folk artists — all of which would have been identified at the time as “primitive.’” For example, the illustrations accompanying the first essay, “Spiritual Possessions” by Franz Marc, include a 15th-century German woodcut, a Chinese painting of cats, two drawings by children, and a German folk art glass painting alongside a recent Cubist painting by Pablo Picasso.

As Kandinsky suggested, what all of these disparate works have in common is their rejection or lack of knowledge of the post-Renaissance Western tradition, with its emphasis on artistic naturalism, scientific knowledge, and technological progress. Starting in the 1700s, a growing number of artists and thinkers saw modern science, technology, and urban life as a threat to humankind’s true spiritual vocation. The simple, even crude works of so-called “primitive” artists were seen as exemplars of an approach to both art and life that emphasized higher spiritual aims.

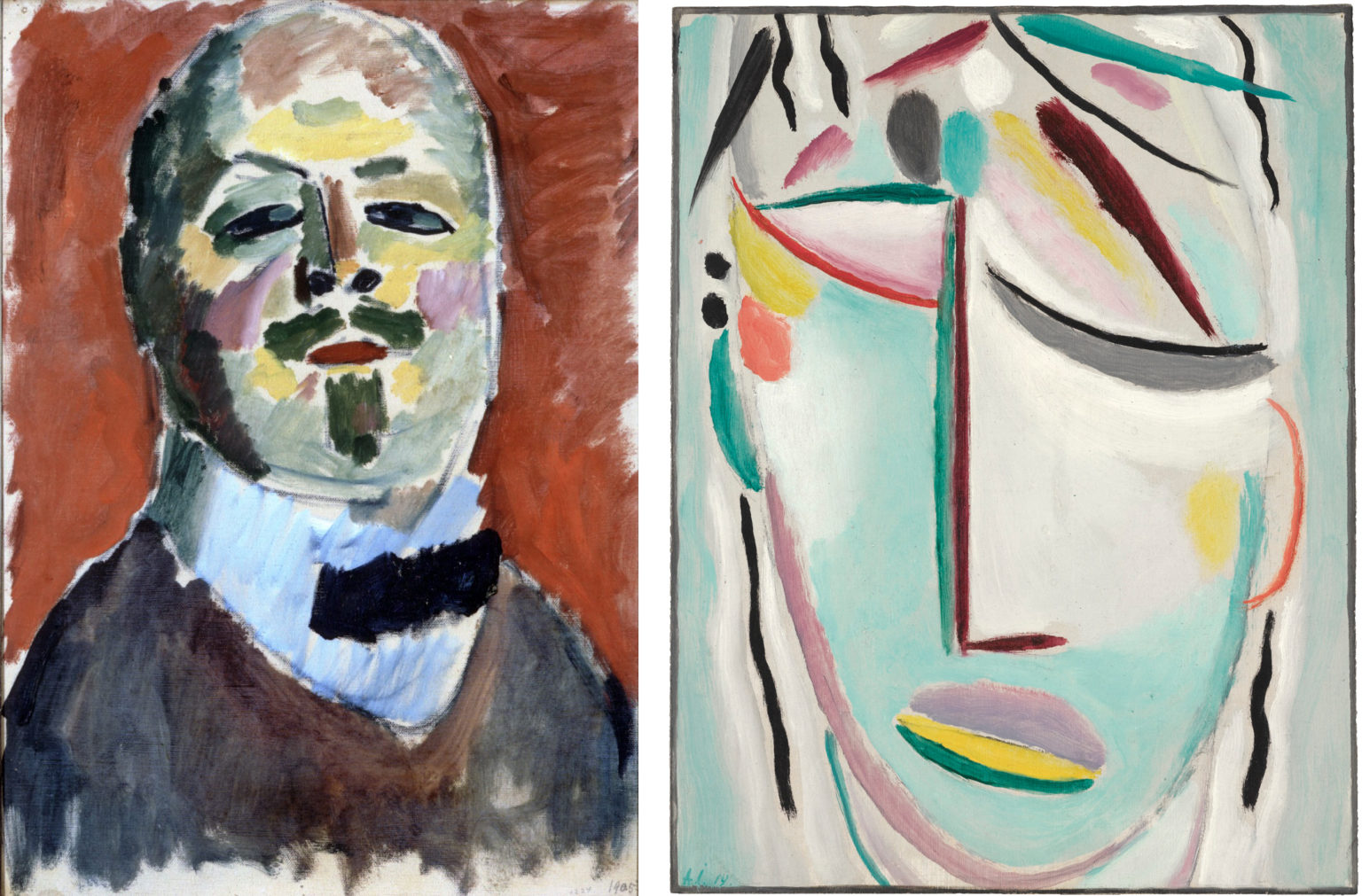

“I did not need nature to prompt me”

Although he studied painting with the Russian Realist Ilya Repin, Alexei von Jawlensky deliberately rejected his training in favor of a childlike simplicity and directness in his later works. For example, his 1905 Self-Portrait, while painterly and simplified, is a convincing likeness of the artist, with naturalistic proportions and chiaroscuro modeling. The coloring is bright, but based on close observation — warmer red tones appear on the cheeks, nose, and forehead, and cooler tones define the eyes, temples, and jawline.

The later work, Savior’s Face, was part of a series of portraits called “mystical” or “abstract heads,” which the artist noted were not executed from nature:

I sat in my studio and painted, and I did not need Nature to prompt me. It was enough for me to immerse myself in myself, to pray and prepare my soul to attain a religious state.