5.4: Japan

- Page ID

- 67050

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)From Shinto shrines and Buddhist gardens to the images of Hiroshige and Mariko Mori.

6th century C.E. - present

A beginner's guide

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

The arts of Japan are profoundly intertwined with this country’s long and complex history. They are also often in dialogue with artistic and cultural developments in other parts of the world. From the earliest aesthetic expressions of the Neolithic period to today’s contemporary art—here is a brief survey to get you started.

Please note that while the material is organized chronologically, it highlights major themes and introduces makers and objects recognized as especially influential.

Jōmon period (c. 10,500 – c. 300 B.C.E.): grasping the world, creating a world

The Jōmon period is Japan’s Neolithic period. People obtained food by gathering, fishing, and hunting and often migrated to cooler or warmer areas as a result of shifts in climate. In Japanese, jōmon means “cord pattern,” which refers to the technique of decorating Jōmon-period pottery.

As in most Neolithic cultures around the world, women made pots by hand. They would build vessels from the bottom up from coils of wet clay, mixed with other materials such as mica and crushed shells. The pots were then smoothed both inside and out and decorated with geometric patterns. The decoration was achieved by pressing cords on the malleable surface of the still moist clay body. Pots were left to dry completely before being fired at a low temperature (most likely, just reaching 900 degrees Celsius) in an outdoor fire pit.

Later in the Jōmon period, vessels presented ever more complex decoration, made through shallow incisions into the wet clay, and were even colored with natural pigments. Jōmon-period cord-marked pottery illustrates the remarkable skill and aesthetic sense of the people who produced them, as well as stylistic diversity of wares from different regions.

Also from the Jōmon period, clay figurines have been found that are known in Japanese as dogū. These typically represent female figures with exaggerated features such as wide or goggled eyes, tiny waists, protruding hips, and sometimes large abdomens suggestive of pregnancy. They are unique to this period, as their production ceased by the 3rd century B.C.E. Their strong association with fertility and mysterious markings “tattooed” onto their clay bodies suggest their potential use in spiritual rituals, perhaps as effigies or images of goddesses. Besides dogū, this period also saw the production of phallic stone objects, which may have been a part of the same fertility rituals and beliefs.

Images of the female body as symbols of fertility are encountered in many parts of the world in the Neolithic period, presenting features unique to the regions and cultures that produced them. The preoccupation with fertility was increasingly twofold, namely the fertility of women and that of the land, as people began cultivating it and transitioning to a settled agricultural society.

Yayoi period (300 B.C.E. – 300 C.E.): influential importations from the Asian continent (I)

People from the Asian continent who were cultivating crops migrated to the Japanese islands. Archaeological evidence suggests that these people gradually absorbed the Jōmon hunter-gatherer population and laid the foundation for a society that cultivated rice in paddy fields, produced bronze and iron tools, and was organized according to a hierarchical social structure. The Yayoi period’s name comes from a neighborhood of Tokyo, Japan’s capital, where artifacts from the period were first discovered.

Yayoi-period artifacts include ceramics that are stylistically very different from the cord-marked Jōmon-period ceramics. Although the same techniques were used, Yayoi pottery has sharper and cleaner shapes and surfaces, including smooth walls, sometimes covered in slip slip, and bases on which the pots could stand without being suspended by rope. Burnished surfaces, finer incisions, and sturdy constructions that suggest an interest in symmetry are characteristic of Yayoi pots.

Slip is a liquid clay mixture used in the production and decoration of pottery.

Some studies suggest that Yayoi pottery is linked to Korean pottery of the time. The Korean influence extends beyond ceramics and can be seen in Yayoi metalwork as well. Notably, Yayoi period clapper-less bronze bells closely resemble much smaller Korean bells that were used to adorn domesticated animals such as horses.

These bells, together with bronze mirrors and occasionally weapons, were buried on hilltops. This practice was seemingly linked to ritual and may have been considered auspicious, perhaps for the fertility of the land in this primarily agricultural society. The magical or ritualistic function of the bells is further suggested by the fact that the bells were not only clapper-less, but they also had walls that were too thin to ring when hit.

The bells became larger later in the Yayoi period, and it is believed that the function of these larger bells was ornamental. Across regions and over the span of a few centuries, such bells varied in size from approximately 10 cm to over 1 meter in height.

Kofun period (ca. 3rd century – 538): influential importations from the Asian continent (II)

The Kofun 古墳 period is so named after the burial mounds of the ruling class. The practice of building tomb mounds of monumental proportions and burying treasures with the deceased arrived from the Asian continent during the 3rd century. Originally unadorned, these tombs became increasingly ornate; by the 6th century, burial chambers had painted decorations. The burial mounds were encircled with stones; hollow clay earthenware, known in Japanese as haniwa 埴輪, were scattered for protection on the land surrounding the mounds. Kofun were typically keyhole-shaped, had several tiers, and were surrounded by moats. The resulting structure amounted to an impressive display of power, advertising the control of the ruling families. The largest kofun is the Nintoku mausoleum, measuring 486 meters!

The hollow clay objects, haniwa, that were scattered around burial mounds in the Kofun period, have a fascinating history in their own right. Initially simple cylinders, haniwa became representational over the centuries, first modeled as houses and animals and ultimately as human figures, typically warriors. The later pieces have been of great help to anthropologists and historians as tokens of the material culture of the Kofun period, offering a glimpse into that society. Whether offerings for the dead or protective barriers meant to guard the tombs, haniwa have a strong aesthetic identity that continues to be a source of inspiration for Japanese ceramists.

Through gradual consolidation of political power, the Kofun-period Yamato clan became a kingdom with seemingly remarkable control over the population. In the 5th century, its center moved to the historical Kawachi and Izumi provinces (on the territory of present-day Osaka prefecture). It is there that the largest of the kofun burial mounds testify to a thriving Yamato society, one that was increasingly more secular and military.

Simultaneously, the potter’s wheel was used for the first time in Japan, likely transmitted from Korea, where it had been adopted from China. This new technology was used to produce what is known as Sue ware—typically bluish-gray or charcoal-white footed jars and pitchers that had been fired in sloped-tunnel, single-chamber kilns (anagama 穴窯) at temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees celsius. Like other types of ancient Japanese pottery, Sue ware continues to be a source of inspiration for ceramists, in Japan and beyond.

Asuka period (538-710): the introduction of Buddhism

The Asuka period is Japan’s first historical period, different from the prehistoric periods reviewed so far because of the introduction of writing via Korea and China. With the Chinese written language also came standardized measuring systems, currency in the form of coins, and the practice of recording history and current events. Standardization and record-keeping also encouraged the crystallization of a centralized, bureaucratic government, modeled on the Chinese.

All this was imported when a new religion—Buddhism—was introduced in Japan, significantly changing Japanese culture and society. Unlike Japan’s indigenous “way of the gods” (Shintō), Buddhism had anthropomorphic representations of deities. After the introduction of Buddhism, we see a shift in the visual and material culture of Shintō. If, before Buddhism, Shintō gods were associated with sacred objects such as mirrors and swords (the imperial insignia), after the introduction of the new religion they began to be represented in anthropomorphic images, although such images were hidden in the inner sanctuaries of Shintō shrines.

Japan’s indigineous religion, Shintō entails belief in the sacred power of animate and inanimate things, as well as ritual practices for the worship of ancestors and gods, known as kami.

By the time Buddhism reached Japan, it had spread from India to China and had undergone several changes in imagery and styles. In Japan, Buddhism profoundly influenced indigenous culture, but it was equally shaped by it, resulting in new forms and modes of expression. The imperial household embarked on major Buddhist commissions. One of the earliest and most spectacular is a temple in Nara, Hōryūji or the “temple of flourishing law.” The founding of Hōryūji is attributed to the ailing emperor Yomei, who died before seeing the temple completed; Yomei’s consort, empress Suiko, and regent Prince Shōtoku (574-622) carried out the late emperor’s wishes. Given the influence of empress Suiko’s Buddhist patronage, the Asuka period is also referred to as the Suiko period. Prince Shōtoku, too, is celebrated as one of the earliest champions of Buddhism in Japan. In fact, a century after his death, he began to be worshipped as an incarnation of the historical Buddha.

Like the enduring legend and legacy of Prince Shōtoku, Hōryūji has had a long and complex life well past the Asuka Period. With structures that vanished in fires and earthquakes as early as the 7th century to the temple’s pagoda that was dismantled and reassembled during World War II, Hōryūji underwent numerous changes and its buildings currently date from the Asuka period to the late 16th century! A complex site with some of the world’s oldest wooden structures, Hōryūji exemplifies ancient Japanese architectural techniques and strategies, including the slight midpoint bulging of round columns, which has been compared to the similar practice of entasis in ancient Greek architecture.

Entasis refers to a slightly convex curve in the shaft of a column, used to correct the visual illusion of concavity that occurs with straight shafts.

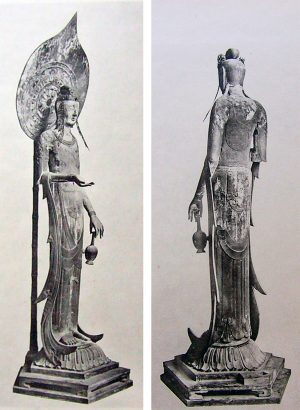

Hōryūji houses one of the best known, albeit mysterious, Buddhist representational sculptures of the Asuka period—the so-called Kudara Kannon 百済観音, a slim and life-size image of the bodhisattva of compassion, sculpted in camphor wood. The first cultural property in Japan to be designated as a “national treasure,” this sculpture first appeared in Japanese records in the 17th century. The “Kudara” in its name, assigned well after the Asuka period, is the Japanese term for Baekje, one of the three historical kingdoms of Korea. The sculpture’s astounding grace derives from its slight smile, slim frame, and flowing lines.

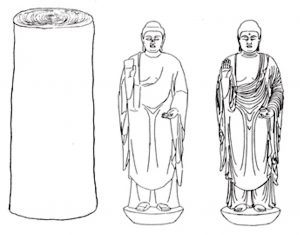

Hōryūji was not the only major temple developed in the Asuka period. When the capital was transferred from Asuka to Nara, a temple known as Hōkōji was relocated as well. In its new location, the temple grew significantly under the name of Gangōji. One of the temple’s treasures is the Asuka daibutsu 飛鳥大仏 or the Great Buddha of Asuka—a devotional image that testifies to the early Buddhist representational tradition in Japan. It is also the oldest of the daibutsu or ‘great Buddhas’—large sculptural devotional images of the Buddha.

Of the original, cast in 609 and attributed to a sculptor of Korean descent, only the face and the fingers of the right hand remain. These details, however, reveal the Chinese-inspired style of Tori Busshi, with soft features, smooth surfaces, and simple and elegant lines.

The late Asuka period, also referred to as the Hakuhō period (late 7th century), saw a momentous transformation of Japanese society, prompted by the so-called Taika reforms. Implemented after the death of Prince Shōtoku, these reforms were modeled on the Chinese system of government and led to a greater centralization of Japanese imperial power. In the realm of Buddhist sculpture, the Hakuhō period marked a rapid expansion and dissemination of Buddhist imagery across Japan. Full-bodied sculptures, like the four Heavenly Kings at Hōryūji, are more visually assertive than the Kudara Kannon and announce the influence of Tang-dynasty Chinese culture. In that, the Hakuhō period can also be considered the first segment of the subsequent era—the Nara period.

Nara period (710-794): the influence of Tang-dynasty Chinese culture

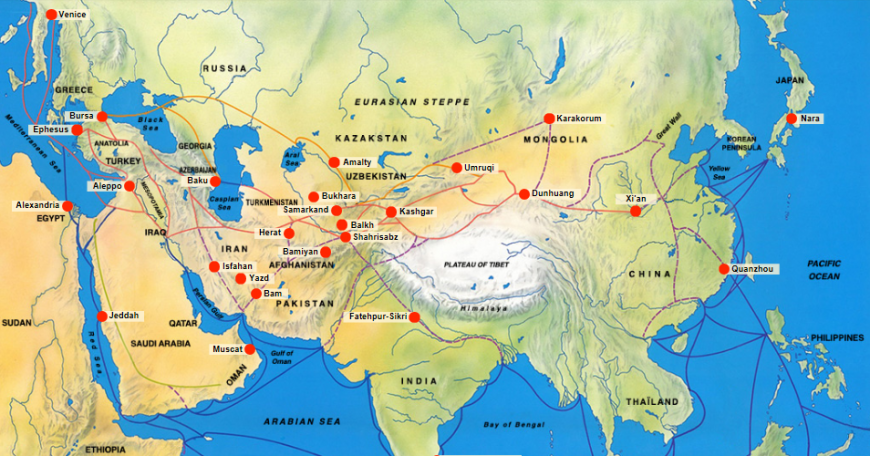

China’s Tang dynasty concentrated such a diverse range of foreign influences that its artistic and cultural characteristics are often referred to as the “Tang international style.” This style had a major impact in Japan as well. Featuring an eclectic and exuberant mix of Central Asian, Persian, Indian, and Southeast Asian motifs, Tang-dynasty visual culture comprised paintings, ceramics, metalware, and textiles.

As these foreign imports were shaping Chinese artistic expression at home, Tang-dynasty artifacts and techniques spread beyond China to neighboring states and along the Silk Road. In Japan, the lavish Tang style was intertwined with Buddhist devotional art.

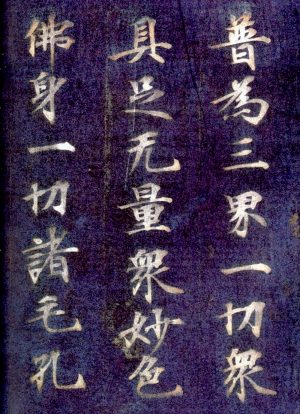

Elegantly transcribed sutras, calligraphed in silver ink on indigo-dyed paper, exemplify this form of Tang-inspired Nara-period art. The painstaking practice of copying Buddhist sacred texts by using precious materials was deemed to earn spiritual merit for everyone involved, from those preparing the materials to the patrons.

The intermingling of political power and Buddhism in the Nara period found its utmost expression in the building of the “great eastern temple” or Tōdaiji and, within this temple, in the casting of the “great Buddha”—a gigantic bronze statue that stood approximately 15 meters/ 16 yards tall and necessitated all available copper in Japan to produce the casting metal.

Although the current statue is a later replacement of the Nara-period artifact, it nonetheless suggests the effect of opulence and awe that it must have achieved in its day. Tōdaiji continued to transform and adapt through the centuries, but its identity is still inextricably linked to the grand scale and commensurate ambition of Nara-period culture.

Sociopolitical power was concentrated, during the Nara period, in the new Heijō capital (today’s city of Nara). Surrounded by Buddhist temples, the Heijō palace was the primary site of imperial power. It also housed subsidiary ministries, modeled on the Chinese centralized government. Generous spaces characterized the palace complex. These spaces accommodated outdoor celebrations, like those of the New Year, but also served to emphasize a sense of distance and therefore the due reverence to the emperor. The palace complex was designed to separate the realm of the emperor from the outside world. That principle of separation was reflected within the palace compound itself, where the emperor’s living quarters were set apart from government buildings. The architectural configuration of the palace reflected the hierarchical configuration of power.

Little of the palace survives today, as various structures within the complex suffered the vicissitudes of nature and history, while others were transferred to the new capital, Heian, for which the next period was named.

Heian period (794-1185): courtly refinement and poetic expression

The new capital, Heian or Heian-kyō, was the city known today as Kyoto. There, during the Heian period, a lavish culture of refinement and poetic subtlety developed, and it would have a lasting influence on Japanese arts. The approximately four centuries that comprise the Heian period can be divided into three sub-periods, each of which contributed major stylistic developments to this culture of courtly refinement. The sub-periods are known as Jōgan, Fujiwara, and Insei.

The so-called Jōgan sub-period, spanning the reigns of two emperors during the second half of the 9th century, was rich in architectural and sculptural projects, largely spurred by the emergence and development of the two branches of Japanese esoteric Buddhism. Two Buddhist monks, Saichō and Kūkai (also known as Kobo Daishi), traveled to China on study missions and, upon their respective returns to Japan, went on to found the two Japanese schools of esoteric Buddhism: Tendai, established by Saichō, and Shingon, established by Kūkai.

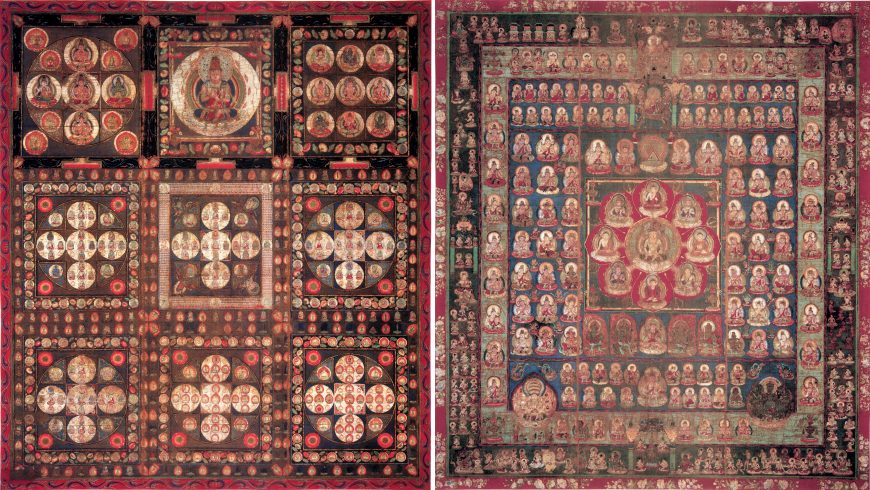

Among the many ideas and objects that they had brought back from China was the Mandala of the Two Worlds, a pair of mandalas that represent the central devotional image of Japan’s schools of esoteric Buddhism. Comprised of the “Womb World Mandala” (mandala of principle) and the “Diamond World Mandala” (mandala of wisdom), the Mandala of the Two Worlds was first assembled as a pair by Kūkai’s teacher in China. One such pair, still housed in Kūkai’s temple in Kyoto (Tōji, the “eastern temple”) represented a blueprint for countless mandalas made in Japan over the centuries.

Mandalas are diagrams of the universe in Hindu and Buddhist symbolism.

It is believed that the consequential trip to China of Saichō and Kūkai was enabled by a member of the Fujiwara, the family that gives the name of one of the Heian sub-periods. The influence of the Fujiwara clan was paramount in the Japanese political and artistic world of the 9th and 10th centuries. Their power was bolstered by the ever-growing shōen system and ensured by their control of the imperial line, as Fujiwara daughters were married to imperial heirs.

Shōen were tax-exempt private estates that undermined state control.

One of the only surviving structures from the Fujiwara period, the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdō-in (a Buddhist temple in Uji, outside Kyoto) is one of Japan’s most valuable cultural assets, with a fascinating, multi-layered story. The Phoenix Hall derives its name from the statues of phoenixes—auspicious mythological birds in East Asian cultures—on its roof.

Completed in 1053, the Phoenix Hall was sponsored by a member of the Fujiwara family—Fujiwara no Yorimichi—a pious believer in yet another type of Buddhism, known as Pure Land. This occurred at a time when many imperial villas like the Byōdō-in were converted into Buddhist temples. Having spread to Japan through the efforts of the monk Hōnen, the Pure Land School of Buddhism taught that enlightenment could be achieved by invoking the name of Amida, the Buddha of infinite light. Practitioners engage in the ritualistic invocation of Amida’s name—the nenbutsu 念仏—hoping to be reborn in Amida’s Pure Land, or the Western Paradise, where they can continue their journey towards enlightenment undisturbed.

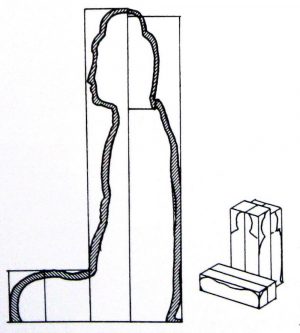

The Amida sculpture in the Phoenix Hall at Byōdō-in is the only work still extant by Jōchō, an influential sculptor who was awarded remarkable distinctions, worked on various commissions from the Fujiwara family, and organized fellow sculptors into a guild. Jōchō’s Amida at Byōdō-in reflects the sculptor’s yosegi-zukuri 寄木造 technique, in which the sculpture is formed from multiple joined pieces of wood. This technique was different from the ichiboku-zukuri 一本造 technique, according to which the sculpture is carved out of a single block of wood.

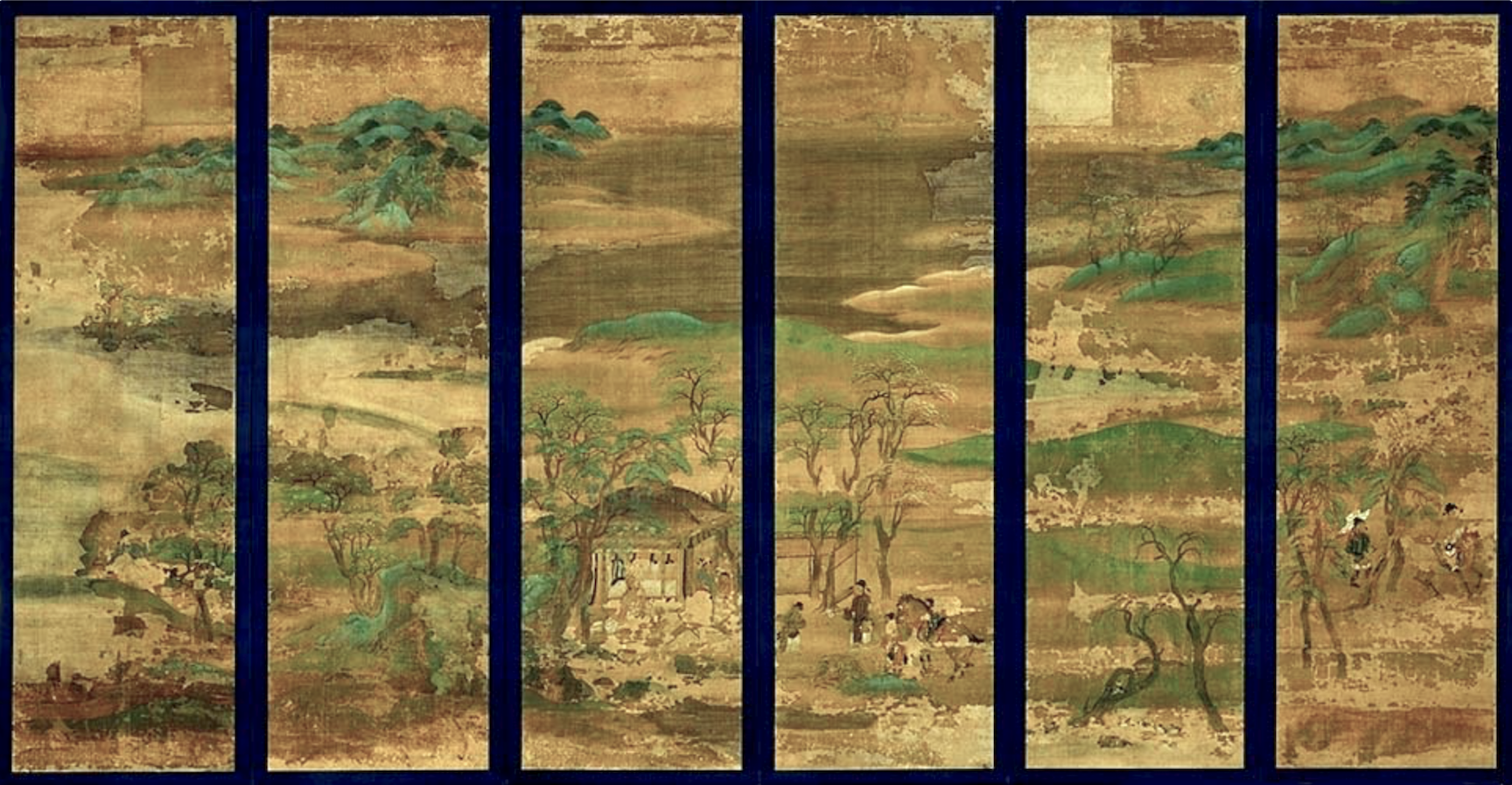

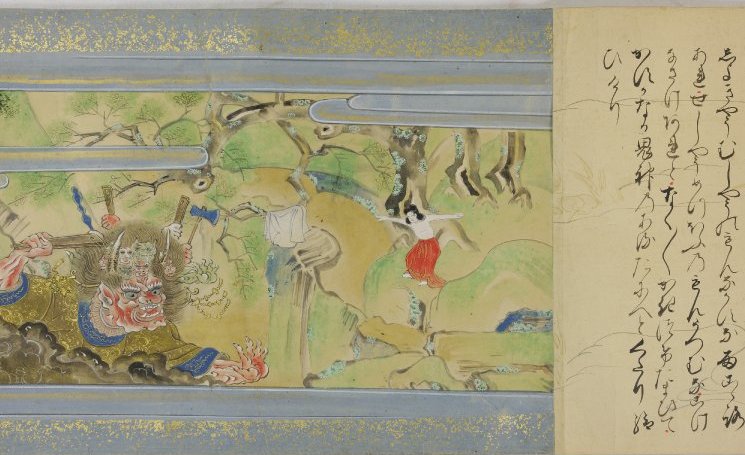

During the Heian period, the style known as yamato-e (大和絵 or 倭絵) is born. Understood as “Japanese” as opposed to “Chinese” or otherwise “foreign,” yamato-e encompasses a wide range of technical and formal characteristics but refers to specific formats—folding screens (byōbu 屏風) and room partitions (shōji 障子)—and specific choices of subject matter—landscapes with recognizably Japanese features and illustrations of Japanese poetry, history, mythology, and folklore.

A favorite subject for late-Heian-period yamato-e was the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語), written in the first years of the 11th century and attributed to a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court, Murasaki Shikibu. A complex novel that focuses on the romantic interests and entanglements of the prince Genji and his entourage, the Tale also provides a fascinating entryway into Heian-period court life, complete with the aesthetic principles and practices that resided at its core.

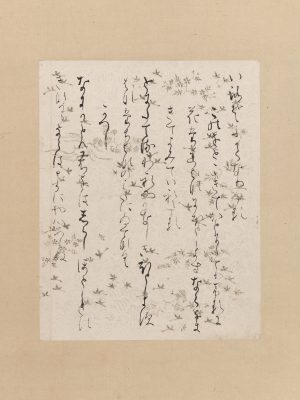

The earliest illustrations of the Tale came in handscroll format. Surviving fragments exemplify the yamato-e mode of narrative painting: illustrations by episode interspersed with passages of text; roofless buildings, multiple viewpoints (typically both frontal and from above), and schematic renditions of faces ( hikime kagihana 引目鈎鼻, literally translated as “drawn-line eyes, hook-shaped nose.”)

A brief review of the Heian period cannot be complete without mention of the development of Japanese poetry, waka in particular. Waka was an integral part of the Tale of Genji, and Murasaki Shikibu came to be known as one of the 6 immortal poets (all of whom were from the Heian period).

Waka are 5-line poems that speak to the confluence of human emotions and observations about the natural world, divided into 2 sections, namely a 2-line part responding to a 3-line part.

Permeating the spirit of Heian-period Japanese poetry and the imagery it inspired was a heightened sense of refinement, expressed in elegant verse, stylized visual motifs, precious materials, and embellished surfaces.

The Insei rule—the third and last of the Heian sub-periods —refers, literally, to the imperial practice of ruling from within a (monastery) compound. During Insei, cloistered emperors had a higher degree of political control. It was during this period that a sense of aesthetic and ethical congruence developed, according to which the beautiful and the good are intrinsically interconnected.

Cloistered emperors retired and counterbalanced the power of the Fujiwara regents from the quarters of a Buddhist monastery, while their chosen successors fulfilled official duties.

Additional resources

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

Kamakura period (1185-1333): new aesthetic directions

The Insei rule gave way to an extra-imperial, although imperially sanctioned, military government, known in Japanese as bakufu. Military leaders—called shōguns—first came from the Minamoto family (whose headquarters in Kamakura gave the name to the period), then power concentrated in the (related) Hōjō family. Eventually, the Minamoto and Hōjō shōguns lost their respective control to internal struggles, the pressure of other clans, and an economy bankrupted by coastline fortifications undertaken in response to two (thwarted) Mongol and Korean invasions.

This binary system of government, comprising the shōgun’s rule and the (nominal) rule of the emperor, significantly contributed to a shift in aesthetic interests and artistic expression. The taste of the new military leaders was different from the aesthetic refinement that dominated Heian-period court culture. They embraced instead a sense of honesty in representation and sought works that emanated robust energy. This new development toward life-likeness and a form of idealized realism is particularly evident in portraiture, both two-dimensional and sculptural.

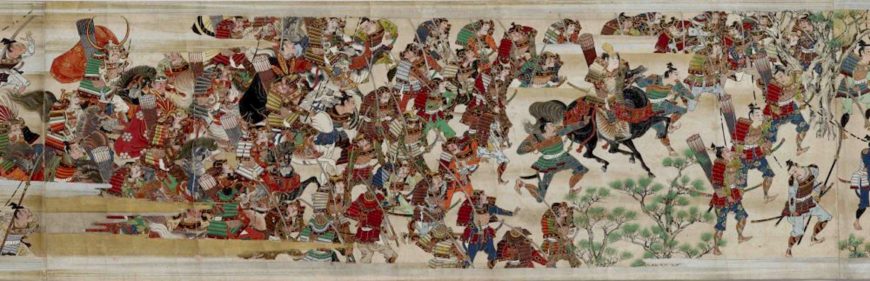

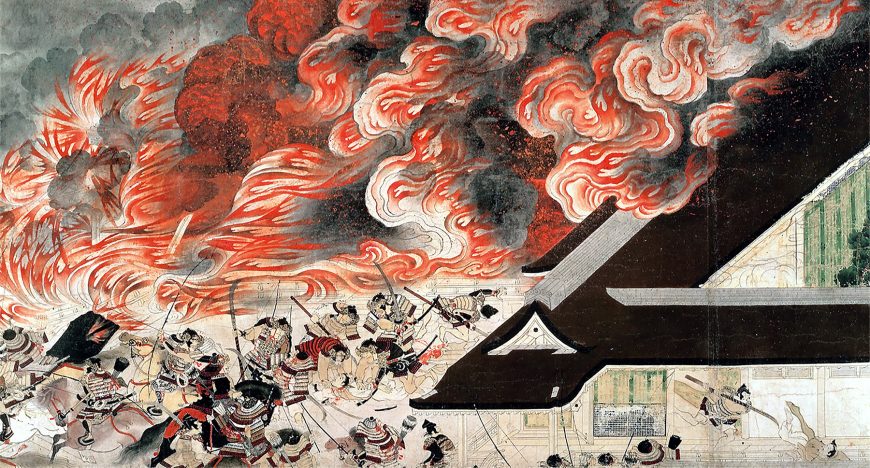

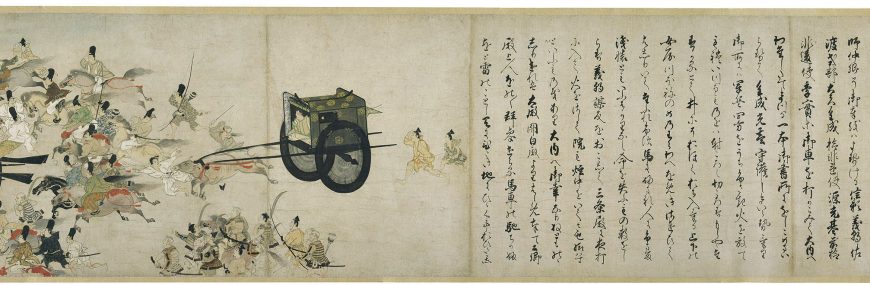

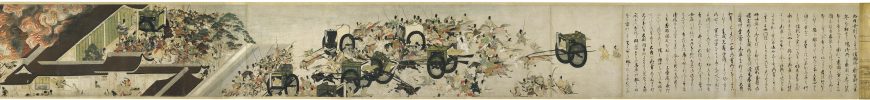

More detailed portraits of lay and religious leaders contrasted with the hikime kagihana (a line for the eye, a hook for the nose) practice of the Heian period, while narrative handscrolls differed from Heian-period Genji-themed pictures in their intricately detailed depictions of historical events. There is no better example than the episode of the “Night Attack on the Sanjō Palace” from the Scroll of Heiji Era Events; here, the visual richness resulting from the imagination of the scroll’s painter(s) makes the depiction appear brutally frank and viscerally impactful.

In sculpture, portrayals of revered monks reach an unprecedented degree of realism, whether modeled on the depicted figures or simply imagined. Sometimes the statues would have rock-crystal inlaid eyes, which heightened the immediacy of the figure’s presence.

The sculptor Unkei and his successors, especially Jōkei, created Buddhist sculptures, carved from multiple blocks of wood, whose facial and bodily features expressed not only an interest in life-likeness, but also a sense of monumentality, sheer energy, and visceral force.

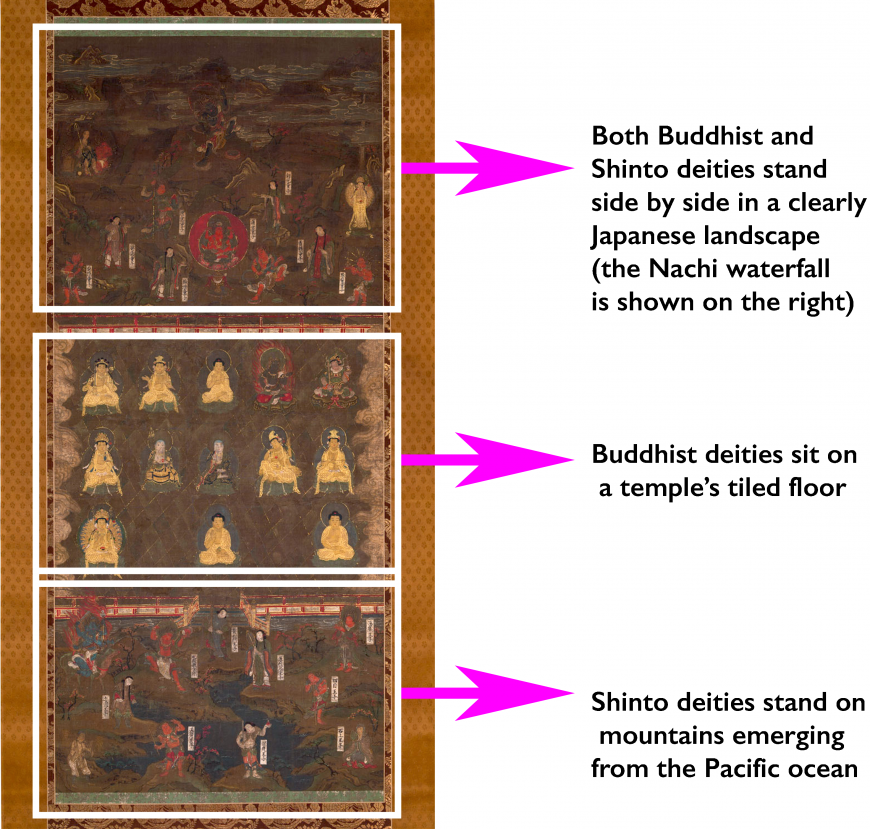

During the Kamakura period, the confluence or syncretism of Buddhism and the indigenous Shintō deepened. Paintings like the 14th-century Kumano shrine mandala contain representations of both Buddhist and Shintō deities, divided into registers that illustrate the fusion of the two world-views against the backdrop of famous sacred sites of Japan.

Nanbokuchō (1333 – 1392) and Muromachi (1392 – 1573) periods: Zen principles, ink painting, and elegant beauty

The Muromachi period, coinciding with the rule of Ashikaga shōguns, was one of the most turbulent and violent in Japanese history. It started with the Nanbokuchō (“the period of the southern and northern courts”), during which political power was split between the Ashikaga-controlled “northern” court and the “southern” and short-lived court of emperor Go-Daigo. The Muromachi period also included the Sengoku (“the age of the country at war”), a period of warfare and chaos in the aftermath of the Ōnin war (1467-1477), triggered by rivalry between provincial warlords.

Two of the Ashikaga shōguns, Yoshimitsu (14th century) and Yoshimasa (15th century), are associated with the Kitayama and Higashiyama cultures, respectively—two sub-periods of cultural efflorescence that nurtured important developments in Japanese arts across mediums. Kitayama culture, so named after an area north of Kyoto where Ashikaga Yoshimitsu had a golden pavilion—Kinkakuji 金閣寺—built for his retirement, is known for the emergence of Noh and the increased influence of Zen Buddhism and Chinese ink painting.

Noh is a type of slow and ritualized dramatic performance with roots in Chinese dramatic arts and infused with Buddhist ideals.

Art coming from contemporaneous Ming-dynasty China as well older Chinese art—dating from the Song and Yuan dynasties, such as the works of Muqi (Mokkei 牧谿 in Japanese)—deeply influenced Japanese arts, especially the emerging local tradition of ink landscape painting.

The most influential Japanese ink master, the 15th-century painter and Zen monk Sesshū Tōyō combined, in his works, Zen principles and lessons learned from Song-dynasty Chinese ink painting—most notably a double sense of austerity and immediacy, highly admired by the Ashikaga shōguns and the samurai class who embraced Zen Buddhism.

Sesshū was a celebrated artist in his own lifetime and continued to be revered as a model by later generations of painters. He became a Zen Buddhist monk at a young age and his master taught him both about Zen and about Chinese ink painting. To perfect his understanding of both, Sesshū traveled to China, where he was honored as a distinguished guest. It is believed that he painted in both palatial and monastic contexts. Upon his return to Japan, he laid the foundation for a new era of Japanese ink painting that straddled religious and lay patronage and combined Chinese and Japanese stylistic elements.

Over the centuries, painters emulated Sesshū’s style, especially his “splashed ink” or “broken ink” technique, and its roots in the literati tradition, some even affixing the painter’s seal to their works, all in an attempt to follow into the footsteps of a revered artist and to attract patrons. The Unkoku school strategically considered its painters to be in the direct lineage of Sesshū. The Hasegawa school similarly traced its stylistic genealogy to Sesshū. These two schools are just two of many examples of Japanese artists embracing a stylistic lineage, whether real or construed, leading back to Sesshū or another master. Legitimizing genealogies are a hallmark of Japanese art history.

In the "splashed ink" or "broken ink" technique, ink is spattered from a brush or directly from the hand to render texture and create a sense of volume.

The advancement of ink painting under the influence of Sesshū is part and parcel of the second Ashikaga-patronized sociocultural sub-period—the so-called Higashiyama culture, named after an area east of Kyoto, where the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa had a silver pavilion—Ginkakuji 銀閣寺—built for his retirement.

The Higashiyama culture entailed programmatic patronage of the arts. During this period, the Kanō school of painting is established and its founder, Masanobu, is appointed official shogunal painter in the late 15th century. At this early stage, Kanō school painting is particularly indebted to Chinese ink painting and the Chinese bird-and-flower tradition. Masanobu’s son, Kanō Motonobu, widened the school’s painting repertoire by introducing color and indigenous motifs and thereby laid the foundation for an appealing synthesis of Chinese and Japanese elements.

The imperial court had its own favored line of painters, who worked in the yamato-e tradition and often specialized in pictures drawn from the Tale of Genji. (Both yamato-e and the Tale of Genji are described in the section on Heian-period art.) These painters are known as the Tosa school; the earliest mention of a painter named Tosa dates from the early 15th century and refers to a painter who was also the governor of the Tosa province. Contemporaneous with the beginnings of the Kanō school was Tosa Mitsunobu, who expanded his school’s repertoire much like Kanō Motonobu did for his school, except in opposite directions: while the Kanō artist added elements of traditional Japanese painting, the Tosa artist began to incorporate elements of Chinese painting. In this sense, the two schools created separate versions of a Chinese-Japanese stylistic synthesis, with the Tosa relying more heavily on the Japanese tradition and the Kanō, on the Chinese.

At the same time, the tea ceremony (chanoyū 茶の湯) emerged as a ritualized form of preparing and enjoying powdered green tea. For this ritual, domestic ash-glazed stoneware vessels, coiled by hand and fired in wood-burning kilns, began to be favored for their austere elegance or sense of sabi 寂—an important Japanese aesthetic concept that stands for seeking beauty in what is simple, solitary, and withered.

These different art forms and mediums—painting, ceramics, dramatic performances, collaborative poetry-writing parties, and tea rituals—converged in shogunal residences like the Golden and Silver Pavilions and especially in the decor of these residences, governed by the aesthetic principle of fūryū 風流—another enduring aesthetic notion in Japan, referring to a refined taste that favors rarified elegance and sensual beauty.

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1615): palatial opulence, bold expression, and the beauty of the imperfect

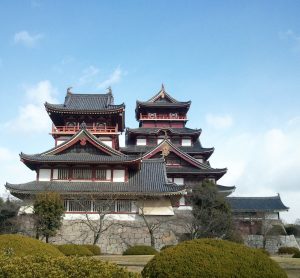

The Azuchi-Momoyama period gets its name from the opulent residences of two warlords who attempted to unify Japan at the end of the Sengoku (“warring states”) era, namely Oda Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle and Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Fushimi or Momoyama Castle. Both castles were not only martial structures for strategic warfare and defense, but also luxurious mansions meant to impress and intimidate political rivals. The architectural style of these residences derived from that of the pavilions built by Ashikaga shōguns during the previous historical period. Also, both castles’ locations were carefully selected for their optimal proximity to the capital—Nobunaga’s castle was built just outside of Kyoto on the shores of lake Biwa, while Hideyoshi’s was in Kyoto itself, in the southeastern ward of Fushimi.

That the two castles were built only 20 years apart reveals the rapid succession of consequential political events that defined the Momoyama period: Oda Nobunaga rose to power starting in 1560 and by 1582, when he was betrayed by his own retainers, he had managed to gain control of most of Japan’s main island of Honshū.

Nobunaga’s warrior, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, succeeded him and used his strategic thinking and negotiation skills to continue the efforts of unification, besides twice invading Korea (in 1592 and 1597). He was succeeded by another former retainer of Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who managed to secure unprecedented power in 1600, winning the most important of Japanese feudal battles, that of Sekigahara.

Only three years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed shōgun by the emperor and spent the remainder of his years consolidating the Tokugawa shōgunate, which would become a 250-year rule of relative peace and prosperity. Only forty years had passed from Nobunaga’s ascension to power to Ieyasu’s appointment as shōgun, but these were years filled with momentous change.

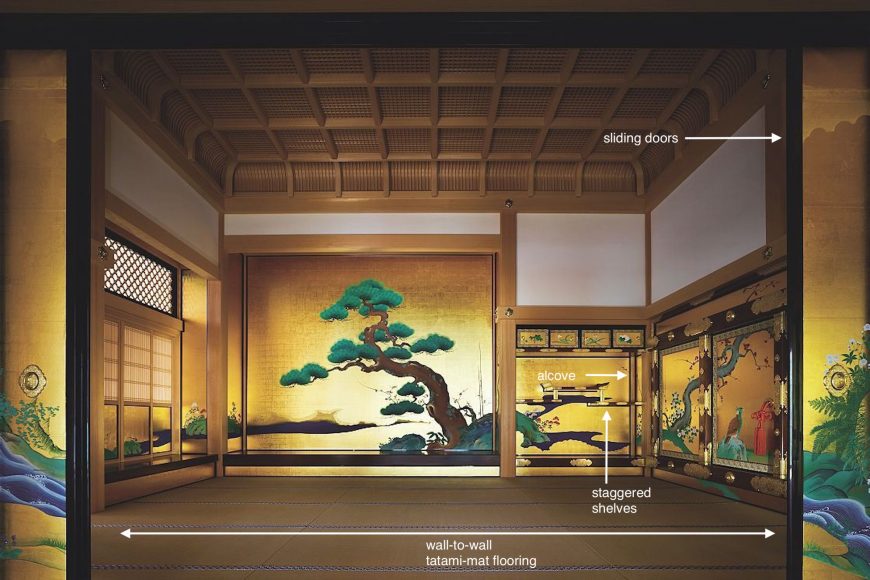

Like other opulent residences of its time, the Azuchi castle comprised numerous buildings in the shoin 書院 architectural style, developed in the Momoyama period. This style entailed a main area flanked by aisles, wall-to-wall tatami-mat flooring, square pillars, and various types of sliding doors and walls that partitioned and reconfigured space. Shoin also featured an alcove in the reception room, known as tokonoma, and elements developed in the Muromachi period for shogunal residences such as staggered shelves and a built-in desk.

In addition to displaying the power of their owners, Nobunaga’s and Hideyoshi’s castles featured the bold and expressive art that characterized the Momoyama period, perhaps mirroring the energy and courage of the era’s military leaders.

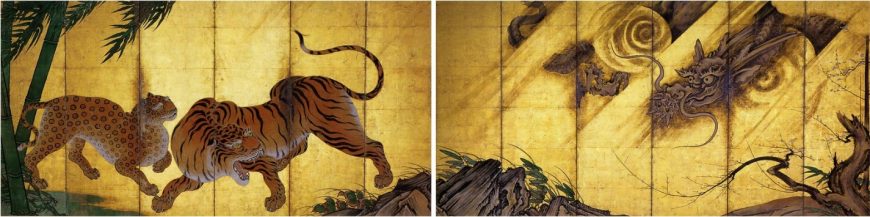

Nobunaga’s Azuchi castle was adorned with the highly expressive paintings of Kanō Eitoku, the grandson of Motonobu, the Kanō painter who established the synthetic Chinese-Japanese aesthetic of the shōgun-patronized school. The very few surviving paintings of Eitoku exemplify this painter’s innovative approach to painting, characterized by dynamic compositions, bold and expressive brushwork, oversized animals, and imagery drawn from nature but set against an opulent golden background that would shimmer in the relatively dark interiors of the warlords’ residences. It can be said that Eitoku’s style matched the power that the painter’s patrons had and wished to put on display.

A rival of the Kanō school emerged in the person of Hasegawa Tōhaku, who may have studied both with Kanō painters and with a pupil of Muromachi-period ink master Sesshū. Tōhaku eventually claimed to be a descendant of Sesshū and developed a bold and highly expressive style, working typically in monochrome ink. His ties to influential tea masters and Zen teachers helped him secure important commissions. Another artist who received major commissions, alongside Kanō Eitoku and Hasegawa Tōhaku, was Kaihō Yūshō, whose military experience and Zen Buddhist training influenced his unique brand of highly charged compositions combining dramatic ink washes and unusually long brushstrokes.

At the intersection of impressive palatial architecture and powerful ink paintings was another art form, nascent in the Muromachi period—the tea ceremony or chanoyu 茶の湯. In the second half of the 16th century, the tea master Sen no Rikyū revolutionized the practice of tea by modeling it on wabi, an aesthetic concept closely related to that of sabi. Wabi refers to finding beauty in simple, even humble things. Embracing the spirit of wabi and sabi, a disciple of Sen no Rikyū, Furuta Oribe, actively supported a new type of local ceramics that became so intertwined with Oribe’s style and efforts that they came to be known as Oribe ware. These new ceramics were radically different in a number of ways. First, they were locally produced and became popular enough to compete with Chinese ceramics in the aesthetic hierarchies of tea masters. Second, they are characterized by a distinctive practice of intentionally distorting the shapes of the vessels in response to the wabi aesthetic that valued the imperfect.

Chanoyu refers to the rituals surrounding the preparation and enjoyment of powdered green tea or matcha.

Sabi is an important Japanese aesthetic concept that stands for seeking beauty in what is simple, solitary, and withered.

The Momoyama period is also remembered for intensified contact with other cultures. Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch ships landed in the Southern island of Kyushu and brought to Japan previously unknown markets, objects, and concepts; firearms, for example, were introduced by the Portuguese as early as 1543. International trade and the spread of Christianity were regarded with suspicion and therefore short-lived, culminating in the self-isolation policy instituted by the Tokugawa. However, trade continued with the Chinese and the Dutch, and a small number of Christians continued to practice in secret.

Despite its brevity and limitations, the late 16th-century encounter with Europeans had a lasting influence. In the port of Nagasaki, Japanese artists were able to observe the foreign visitors’ dress, manners, and habits, and a new painting genre emerged, the so-called nanban (literally, “Southern barbarians,” the name given in Japan to the Europeans who arrived from India via a Southern sea route). Nanban paintings depict not only European priests and traders, but also Goanese sailors, who traveled with the merchants and missionaries, and even Caucasian women, although there were no women among those who landed in Japan at the time. Nanban screens became very popular and many copies were made, increasingly more removed from first-hand observations and reliant upon the painters’ imagination.

Nanban imagery was not confined to painted folding screens; we encounter nanban motifs in other mediums such as ceramics and lacquerware. The inside of the writing box shown here presents images of Portuguese and Indian or African figures, while the outside is decorated with traditional Japanese motifs of fallen cherry blossoms. Objects such as this writing box exemplify not only the integration of nanban imagery in Japanese visual culture, but also an important Japanese aesthetic principle, that of kazari. Translated as both “ornament” and “the act of decoration,” kazari is also a mode of display—and so much more than that. Above all, kazari is an organizing principle of aesthetic and social dimensions that seeks visually and conceptually stimulating juxtapositions that transform the appearance of both objects and spaces, activating the viewer’s own creativity and imagination.

Additional resources:

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

Edo period: artisans, merchants, and a flourishing urban culture

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory and territorial unification paved the way to a powerful new government. The Tokugawa shogunate would rule for over 250 years—a period of relative peace and increased prosperity. A vibrant urban culture developed in the city of Edo (today’s Tokyo) as well as in Kyoto and elsewhere. Artisans and merchants became important producers and consumers of new forms of visual and material culture. Often referred to as Japan’s “early modern” era, the long-lived Edo period is divided in multiple sub-periods, the first of which are the Kan’ei and Genroku eras, spanning the period from the 1620s to the early 1700s.

During the Kan’ei era, the Kanō school of painting, founded in the Muromachi period, flourished under the leadership of three of its most characteristic painters: Kanō Tan’yū, Kanō Sanraku, and Kanō Sansetsu. Their styles both emulated and departed from the formidable painting of Kanō Eitoku (discussed in the Momoyama-period section). Tan’yū was Eitoku’s grandson, Sanraku was his adopted son, and Sansetsu was Sanraku’s son-in-law (whom Sanraku eventually adopted as heir).

Their respective styles shared a creative tension between two diverging artistic directions: on the one hand, they were deeply influenced by the boldly expressive and monumental painting style of Eitoku; on the other hand, they adopted a less dramatic and subtly elegant manner, including a return to Chinese models and the earlier style of the Kanō school.

Tan’yū, in particular, spearheaded this conservative turn. His move to Edo as the painter of the Tokugawa shōgun marked a break with the Kyoto-based Kanō painters (including Sanraku and Sansetsu), one that was reflected in contemporaneous treatises that opined on issues of hierarchy and legitimacy within the school.

A versatile artist steeped in the Chinese tradition, Tan’yū was a connoisseur and collector of Chinese paintings. Drawing on his erudite visual vocabulary, Tan’yū painted both poetic landscapes in monochrome ink, typically evocative of classical subjects, and polychrome paintings in the Japanese style, accommodating large-scale commissions for palatial settings. In appreciation of his work, he was awarded, at age 61, the honorific title Hōin (“Seal of the Buddhist Law”).

The Kan’ei and Genroku eras witnessed major developments in another medium, namely porcelain. The pioneers of Japanese porcelain were Korean potters brought to Japan after Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s incursions into Korea during the Momoyama period. These potters settled in Kyushu and paved the way for one of the world’s most innovative and prolific porcelain centers. Arita, Imari, Kakiemon are now household names, in part because of the 17th-century export of such wares from Northern Kyushu via the Dutch East India Company. This international trade company had contributed significantly to the global appeal of Chinese porcelain, particularly the blue-and-white variety. Despite the Tokugawa’s policy of self-isolation, the exception of allowing some Chinese and Dutch agents to continue international trade, combined with the political turmoil in China caused by the downfall of the Ming dynasty, created the optimal context for the Dutch to replace Chinese blue-and-white porcelain with Japanese porcelain in global trade. Japanese export ware, often referred to as Imari ware, emulated Chinese blue-and-white porcelain and reflected the Western tastes to which it catered.

Among the different porcelain kilns of northern Kyushu, Nabeshima ware was not for export but produced exclusively for the domestic market. The lord of Nabeshima, who had brought the Korean potters to his domain, embraced the local production that developed in the 17th century and patronized a special kiln whose porcelain he offered as strategic gifts to the shogun and other feudal lords. With its production processes kept secret, Nabeshima porcelain is distinguishable by its exquisite surfaces, adorned with delicate motifs drawn not from Chinese or European sources, but from the traditional Japanese visual repertory.

With its smooth surfaces and well-defined shapes, porcelain was markedly different from the stoneware produced in other ceramic centers of Japan, like the Oribe ware for tea rituals (described in the section on the Momoyama period). During the Edo period, the tea ceremony—both chanoyu and sencha, a different type of ritual for the preparation and enjoyment of steeped leaf tea—continued to flourish. Sencha, in particular, was integral to the literati culture. Japanese literati or bunjin modeled themselves on Chinese scholar-philosophers who were well-versed in painting, calligraphy, and writing poetry. As scholars with artistic pursuits, bunjin were not professional painters, but used painting—especially spontaneous renderings of landscapes, poems, and Chinese and Japanese traditional motifs in ink wash—as ways of expressing the inner energy of cultivated spirits that sought to achieve excellence by removing themselves from society and even defying societal norms. This model of reclusion was particularly embraced in periods of political unrest, which was definitely the case in Japan at the end of the 16th century during the turmoil that characterized Momoyama, the 40-year span that led to the Edo period. Gradually, literati practices developed a core tension between the rebellious and the highly individualistic, on the one hand, and the ritualistic and the normative, on the other, as traditions and lineages began to became more rigid over time.

Bunjinga, literally translatable as “literati painting,” refers to painting practiced by these learned men. Literati painting often brought together references to both classical Chinese themes and local and contemporaneous literary sources, especially poems, often written by the painters themselves. The 18th-century haikai-no-renga poet Yosa Buson was also an accomplished painter and, in the collaborative spirit of haikai-no-renga, co-authored, with Ike no Taiga, a pair of albums on the Chinese theme of the “ten conveniences” and “ten pleasures” of life, combining idealized depictions of nature (mostly by Buson) with anecdotal renditions of human activities (mostly by Taiga). The collaboration between Buson and Taiga was both collegial and competitive, calling to mind the centuries-old Japanese tradition of poetry and picture contests that showcased talent and skill.

A foil to Buson’s and Taiga’s approach to painting was the renewed search for realism of painter Maruyama Okyo. His naturalistic rendition of birds and animals, human figures, and landscapes contrasted with the literati mode by focusing on a rational regimen of visual representation, grounded in observation of the natural world. Trained in the European techniques of shading and one-point perspective, Okyo nonetheless created a synthesis of western-inspired naturalism and traditional Japanese techniques, styles, and subject matter. Okyo’s mode of painting was transmitted via the Maruyama-Shijō school, that Okyo first established as the Maruyama school. It was continued by Matsumura Goshun (whose studio was on the Shijō street in Kyoto), a painter who first studied with Buson and then turned to Okyo. These two closely related schools have been referred to as one entity since the late Edo period, when the distinctions between the two had faded. One of the most notable painters in the lineage of Goshun was Shibata Zeshin, a disciple of one of Goshun’s students, and an innovative painter and lacquer artist.

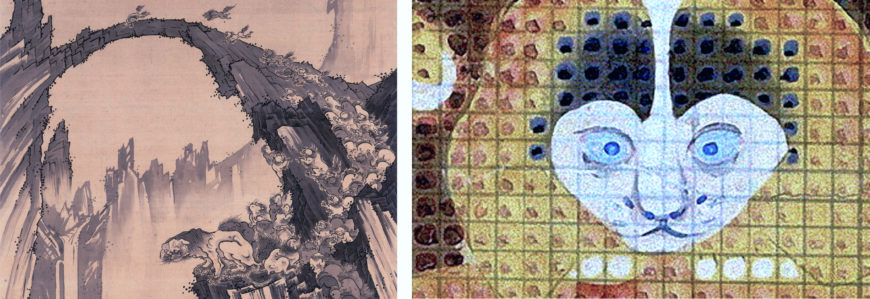

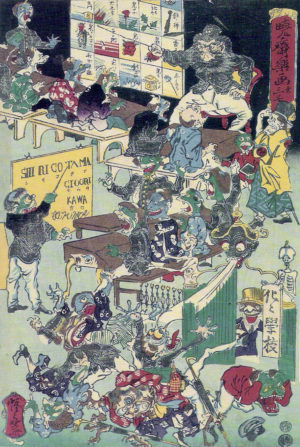

Painters working outside established schools like the Tosa and the Kanō diverged from established modes of painting to varying degrees. Those whose styles were particularly unconventional have been recently re-evaluated as forming a “lineage of eccentrics” by Japanese art historian Tsuji Nobuo. Included in this “lineage” are Iwasa Matabei, Kano Sansetsu, Ito Jakuchu, Soga Shohaku, Nagasawa Rosetsu and Utagawa Kuniyoshi—each of whom had individual trajectories in their respective processes of maturing as visual artists. What they shared was a highly personal approach to painting, often characterized by unusual techniques and atypical subject matter. In Lions at the Stone Bridge at Mt. Tiantai, Soga Shōhaku chose a rarely depicted Buddhist theme and imagined it in novel ways, adding a whimsical dimension to it. In Birds, Animals, and Flowering Plants in Imaginary Scene, Itō Jakuchū painstakingly painted no fewer than 43,000 colored squares to create a fantastical, mosaic-like composition.

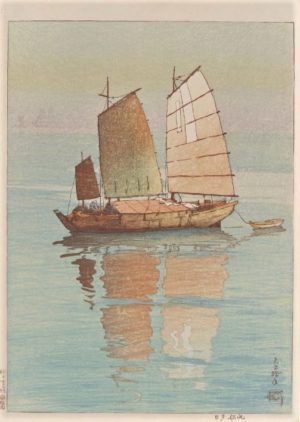

During the Edo period, a bustling urban culture developed. Merchants, craftsmen, and entertainers helped shape cultural and artistic tastes through their products and programs. Collaborative linked-verse parties and new forms of entertainment like kabuki theater became staples of the urban lifestyle. Tourism, too, gained in popularity as travelers went on pilgrimages to shrines, temples, and famous sites (meisho 名所), often associated with classical poems and traditional tales. All these cultural practices were mirrored in the popular paintings and prints known collectively as ukiyo-e 浮世絵. Literally “pictures of the floating world,” ukiyo-e can be best defined as genre painting for and about “common people” (shōmin 庶民)—members of the middle class of Edo-period Japanese society.

Trained in his family’s textile business, 17th-century painter Hishikawa Moronobu was the earliest of the ukiyo-e masters. He focused on images of beautiful women (bijin 美人) and worked both in painting and woodblock printing. His depiction of women and lovers in Edo’s pleasure quarters deeply influenced subsequent ukiyo-e painters and print designers, notably Miyagawa Chōshun. Initially educated in the Tosa school, Chōshun signed his works by adding “yamato-e” to his name—a practice indicating that in its early days, ukiyo-e was regarded as a successor to the yamato-e style.

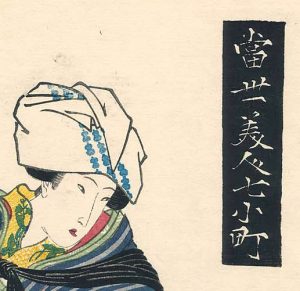

Contemporaneous with the ukiyo-e master Hishikawa Moronobu was the painter Iwasa Matabei, who, like Moronobu and his followers, saw himself as an heir to the yamato-e and Tosa-school traditions. Given his anecdotal painting style and his allegiance to Japanese subjects and painting techniques, Matabei is often regarded as a founding figure of ukiyo-e along with Moronobu. Matabei drew inspiration for his paintings from the classics of Japanese literature such as the Tale of Genji. However, in the spirit of ukiyo-e, his paintings are infused with a sense of everyday life and personal experience. The highly personal dimension of his art made others think of Matabei as one of the “eccentrics” (used here in the sense previously explained in relation to Shōhaku and Jakuchū, and aligned with the definition of art historian Tsuji Nobuo). Whether Tosa, ukiyo-e, or eccentric, Matabei broke with tradition by focusing on contemporaneous experiences and aspects of everyday life. Often, these themes were playfully intertwined with classical subject matter, resulting in a visual simile, which was at times parody, known as mitate. Realities of the present were superimposed over classical or mythic themes of the past. This practice ranges in Edo-period painting from an emphasis on the mundane and the anecdotal, as seen in Matabei’s compositions, to playful depictions of contemporaneous figures (such as beautiful women and kabuki actors) in the guise of legendary or historical figures such as poets and warriors, as seen later in the works of 18th- and 19th-century ukiyo-e artists like Andō (Utagawa) Hiroshige and Utagawa Kunisada.

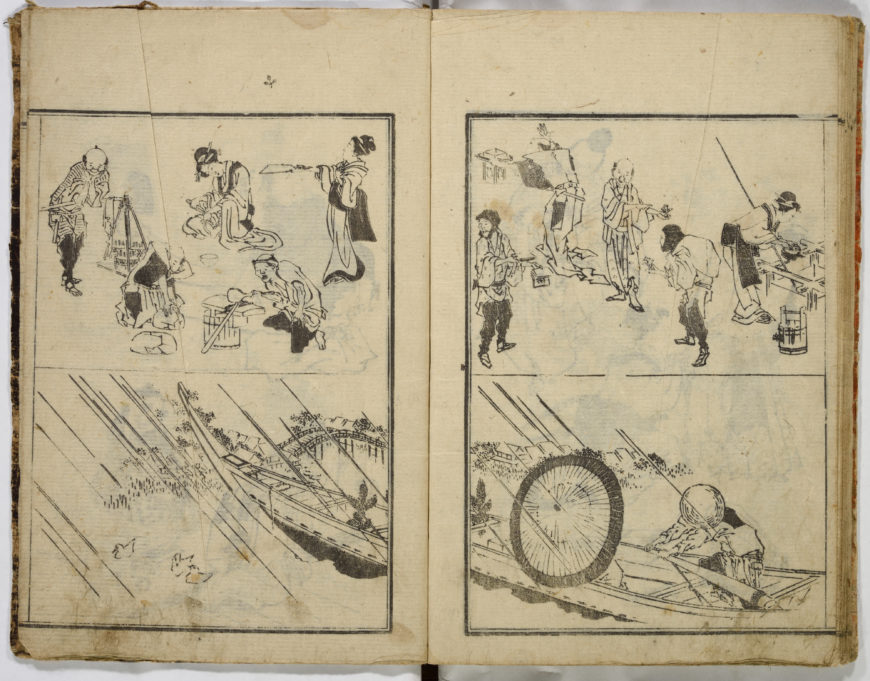

Ukiyo-e images were made available in a variety of formats, from paintings and surimono to picture books (ehon 画本) and loose woodblock prints, often conceived in series (e.g. thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, seven episodes in the life of 9th-century poetess Ono no Komachi). One of the best known ukiyo-e masters and an emblem for Japanese art in the western world, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) not only designed woodblock print series and picture books, but also authored numerous paintings. Leading a frugal life and living in unkempt abodes, Hokusai was remarkably prolific over his long life, adopting various monikers and carefully dating his works by indicating how old he was when he painted them. Hokusai is deservedly famous for his exceptional draughtsmanship and exuberant imagination, coupled with a fine understanding of Japanese life and culture, both classical and contemporaneous. Like other Edo-period painters, he often inserted himself in his own work via quasi-self-portraits and reflections on impermanence and old age.

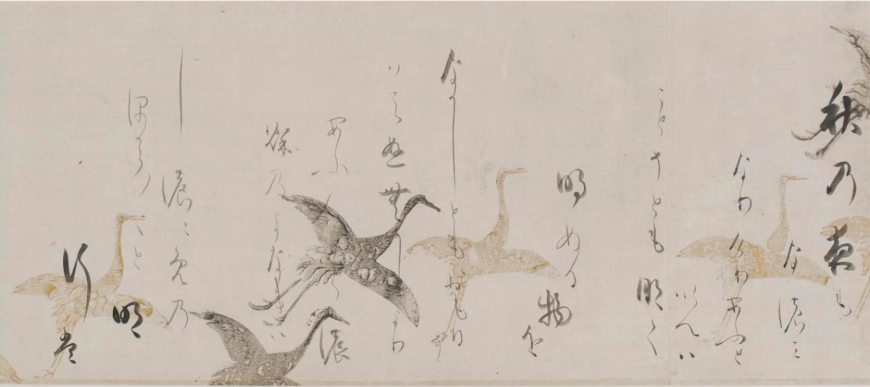

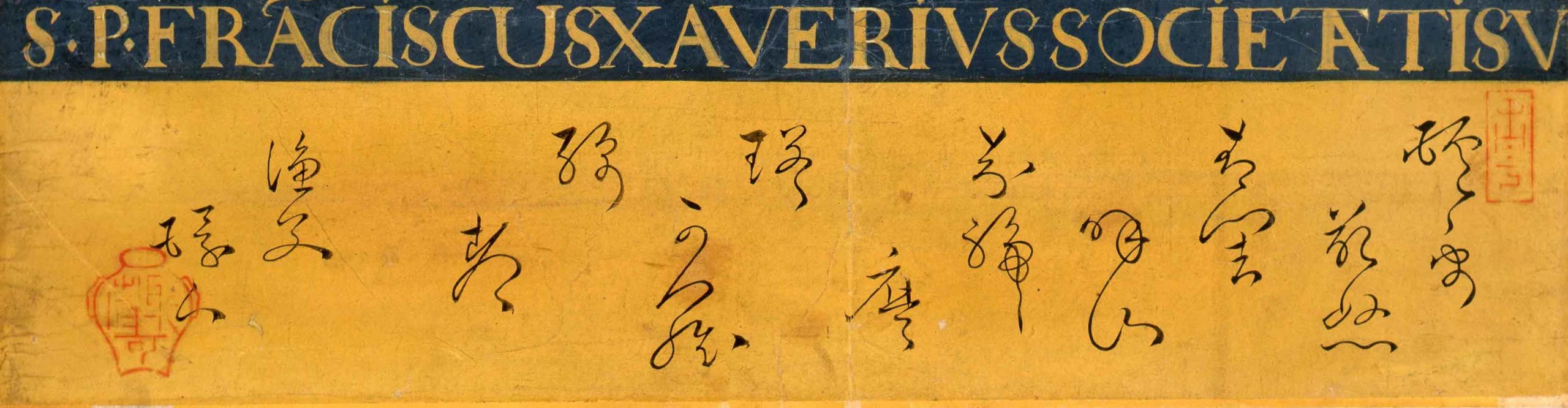

The Edo period saw an intensified circulation of visual vocabulary and aesthetic principles between mediums (paintings, ceramics, lacquerware, and textiles often shared the similar motifs) and crossing different registers of culture from design to popular culture to nostalgia for a romanticized pre-modern past. These intersections were further enabled by collaborations between artists of different specializations. One of the most consequential of these collaborations was that between the Kyoto-based, 17th-century painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu and calligrapher and ceramist Hon’ami Kōetsu.

Their combined practice entailed an elegant aesthetic emphasizing traditional cultural references shared across painting, poetry, calligraphy, lacquer, ceramics, and tea ritual.

Along with potter Nonomura Ninsei, Kōetsu was among the first to sign their pottery in Japan. He would shape his tea bowls, then send them to the Raku-ware workshop to have the bowls glazed and fired. Kōetsu worked across multiple media and his collaborations with painters and potters contributed to a more unified visual culture. As is the case with Japanese art across the ages, lineages played a vital role in the survival and transformation of Sōtatsu’s and Kōetsu’s aesthetic programs.

The intertwined styles of these two 17th-century artists were emulated and consolidated by the early-18th-century artists Ogata Kōrin and his brother Ogata Kenzan, who became school leaders in their own right. A familial relationship doubled this stylistic genealogy: Kōrin and Kenzan’s great-grandmother was an elder sister of Kōetsu. And the two brothers collaborated on occasion. Kōrin specialized in painting, while Kenzan became one of the most influential names in Kyoto-area ceramics. Later generations of potters emulated and even copied Kenzan’s style, while Kōrin gave his name to a new school, Rinpa (“Rin 琳” from “Kōrin 光琳” + “pa/ ha 派”, meaning “school”), that traced its aesthetic origins to Kōrin’s and Kenzan’s models, namely Sōtatsu and Kōetsu. Rinpa artists’ refined and ingenious designs were based on traditional themes and motifs, and rendered in gold, silver, and bold colors. They worked across mediums and genres ranging from painting to lacquer and from episodes in the Tale of Genji to depictions of the four seasons.

Additional resources

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Nobuo Tsuji, translated by Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, History of Art in Japan (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2019)

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periodsFrom the Meiji restoration (1868) to the first year of Reiwa (2019): modern and contemporary art, part I

Meiji period (1868-1912)

1868 was a watershed year for Japan. After over two centuries of shogunal rule, practical political power was restored to the emperor (Meiji). 15 years earlier, the American commodore Matthew Perry led a military and diplomatic expedition to Japan, opening the country to foreign trade and thereby ending the Tokugawa-imposed self-isolation policy. The effects of this forcible “opening” were manifold and deeply affected Japan’s social and cultural fabric. Japan began to participate in World’s Fairs, curating displays of samples of Japanese cultural tradition designed for the outside world to see, and often taking the form of new porcelain vases that impressed through their monumental scale, technical excellence, and intricate decoration.

In the realm of painting, the 1870s saw a new mode of image-making that embraced western styles and techniques, known in Japanese as yōga 洋画 (“Western-style painting.”) A pioneering yōga artist, Takahashi Yuichi assisted Antonio Fontanesi, the “foreign advisor” appointed by the Meiji government to teach oil painting at the newly established Technical Fine Arts School in Tokyo. Further developed by painters like Kuroda Seiki, who studied extensively in Paris and worked in Japan into the 1920s, yōga largely embraced contemporaneous styles of French painting, from the Barbizon School to Impressionism, and their connected practices, from painting from nature to favoring subject matter drawn from the here and now.

The Barbizon School comprised French artists who moved toward realism in the landscapes they painted in the environs of the Fontainebleau forest outside Paris, beginning in the 1830s, deeply influenced by English painter John Constable.

As a foil to yōga, other Japanese visual artists developed a parallel mode of painting, known as nihonga 日本画 (literally, “Japanese painting.”) Rejecting a straightforward adoption of techniques and styles from Euro-American pictorial traditions, nihonga was not a direct continuation of the earlier yamato-e either. Instead, nihonga broadened the traditional themes of yamato-e, created new blends of Japanese stylistic traditions like Kanō and Rinpa, and even incorporated western modes of pictorial realism in its reinvention of Japanese painting.

Born in the Heian period, yamato-e is a painting style understood as “Japanese” as opposed to “Chinese” or otherwise “foreign.” It refers to specific formats, i.e. folding screens and room partitions, and specific themes, i.e. landscapes with recognizably Japanese features and illustrations of Japanese poetry, history, and mythology.

Two artists who significantly shaped nihonga were Kanō Hōgai and Yokoyama Taikan. Remembered as the last great master of the Kanō school, Kanō Hōgai helped pioneer nihonga alongside fellow painter Hashimoto Gahō, himself trained in the Kanō style, and Ernest Fenollosa, an American poet and art critic who assumed important cultural positions in Meiji-period Japan, as professor of philosophy and curator at the newly established Tokyo Imperial University and Imperial Museum, respectively. Modeled on European and American universities and museums, such institutions altered the old structures of the Japanese cultural field. New words became necessary in the Japanese language to translate and use foreign concepts such as “fine art” or “artist.” Thinkers like Fenollosa or Okakura Kakuzō—a sort of cultural ambassador who explained, through his subjective lens, Japanese culture to elite American audiences—affected both the production and the reception of what constituted “Japanese art” in the Meiji period. Born out of Okakura’s teachings on traditional Japanese culture was the quintessentially nihonga style of painter Yokoyama Taikan. His paintings combine canonically Japanese and western-inspired elements with unconventional techniques and high symbolic content.

Yet other modes of painting co-existed with the strong yōga and nihonga trends. Somewhat aligned with Euro-American post-Impressionism, the artist Tomioka Tessai created his individualistic style through an inventive blend of influences, largely drawn from classical Japanese and Chinese sources. Tessai’s mentor, friend, and frequent collaborator was Otagaki Rengetsu, an artist and Buddhist nun who expressed her unique style via pottery, poetry, painting, and calligraphy. Another idiosyncratic artist of the period was Kawanabe Kyōsai, who “translated” his experience of the drastic changes that Japan underwent in the 19th century into caricatures within an exuberantly inventive pictorial realm. Through such artists, the Meiji period furthered the spirit of centuries of poetic and playful interplay among mediums and styles in Japanese arts.

Spurred by new ideas about the nation-state and by the reconfiguration of society in the modern era, Japanese urban life was transformed in the Meiji period. With this transformation came different modes of living and new architectural styles for buildings that housed newly established public institutions and for family homes, influenced by western-centric concepts of domesticity. Modeled on western architecture, buildings were built with brick and stone instead of the traditional wood. Merging international and indigenous elements, an eclectic architectural style emerged, championed by architects like Itō Chūta, who also helped establish cultural preservation laws for ancient structures such as temples and shrines.

Taishō period (1912-1926)

The Taishō period continued the process of adoption and transformation of foreign models. During this period Japan participated in World War I and continued its colonial rule of Korea and Taiwan, occupations dating from the Meiji period. In the cultural field, the eclectic style that had emerged in architecture continued to flourish, with structures emulating modernist trends like Bauhaus and Art Deco. The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, a natural disaster of catastrophic proportions, not only destroyed buildings and other cultural properties, but marked a shift in Japanese society from the optimism of the Taishō period to the radicalized nationalism of subsequent decades.

The Yasuda auditorium, built in 1925 on the campus of the University of Tokyo, epitomizes the brief but consequential Taishō period. Designed in an Art Deco mode and reminiscent of the campus of the University of Cambridge, the Yasuda auditorium was sponsored by one of the founders of the Yasuda zaibatsu. It was intended as a temporary resting facility for the emperor when he visited the university. As such, the auditorium embodied the socio-cultural influence of the new financial magnates, the rising nationalism concentrated in the persona of the emperor, the adoption of the European Art-Deco architectural style, and the affirmation of the university as a modern research center.

Zaibatsu refers to Japanese industrial and financial conglomerates whose economic and socio-political influence dominated Japan from the Meiji period to the end of World War II.

Nihonga, or (modern) Japanese painting, continued to develop at the intersection of Japanese tradition, western techniques, and individual styles. The Nihonga painter Yokoyama Taikan resurrected the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Art Institute) after it had lapsed following the death of its leader, the controversial but influential thinker Okakura Kakuzō. Such developments ensured a continuation of Meiji-period discourses on the arts, entailing the adoption of western notions and terms and the formulation and crystallization of new concepts, all reflected in newly coined Japanese-language words.

An equivalent to Nihonga was the shin hanga phenomenon, namely the formation of new modes and styles of printmaking that simultaneously revitalized ukiyo-e (as defined in the section on Edo-period arts) and incorporated elements of modern design and western-inspired realism. While shin hanga largely preserved the multiple hands traditionally involved in the design and production of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, another mode of Japanese printmaking that emerged in the 1910s, known as sōsaku hanga, emphasized individual expression and featured a sole creator in charge of all aspects of the print’s production (from drawing to carving to printing). Sōsaku hanga resonated, and drew upon, contemporaneous thinkers and writers like Natsume Sōseki who advocated self-expression.

From the Meiji restoration (1868) to the first year of Reiwa (2019): modern and contemporary art, part II

Shōwa period (1926-1989)

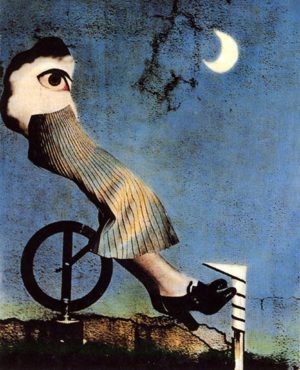

The years leading to Japan’s involvement in World War II saw the rise of militarism, ultra-nationalism, and increasing imperialistic ambitions, fueled in part by Japan’s emulation of western colonialism. In the 1920s and 30s, Japanese poets, photographers, and painters who had studied abroad developed, in Japan, styles aligned with contemporaneous global art movements, combining elements of surrealism, absurdist Dada, and futurism. For example, the paintings of Fukuzawa Ichirō combined surrealist imagery with political commentary; Hirai Terushichi made use of color painting and photomontage to create photographic prints that blurred the boundary between reality and imagination.

Such artists were silenced in 1941 by the Japanese “thought police” that aimed to control any and all ideologies that seemed to pose a threat to the ideals and agenda of the Nazi-allied Empire of Japan. War-time painting depicting military men and battles came to be heavily criticized after the war for their political charge, but recent scholarship by Ikeda Asato suggests that seemingly apolitical paintings of the pre-war period, which romanticized subjects of “authentic” Japanese culture such as Mount Fuji or bijin (“beautiful women”), can also be understood as having supported the militaristic state ideology of the time.

Postwar Japan was a period of unprecedented change. From the end of the war in 1945 to 1952, Japan was occupied by the victorious Allied forces, led by American General Douglas MacArthur. From 1952 to the death of the Shōwa emperor (Hirohito) in 1989, Japan witnessed a successful U.S.-influenced economic redevelopment. In the cultural sphere, as early as 1954, the newly established Gutai art association promoted “concrete” or “embodied” artistic expressions, pushing abstraction to its limits and foreshadowing the performance and conceptual art of the 1960s and 70s.

In those later decades, the exploration of materiality continued to preoccupy artists of the so-called mono-ha (literally “school of things”), including the Korean Lee Ufan. Mono-ha artists created works that tested the tension between natural and manmade materials and between their chosen materials and the environment in which they were placed. Mono-ha artists may have been influenced by the sociopolitical climate of distrust, protest, and counterculture that dominated the 60s and 70s. Referring to one of his most influential works, Phase: Mother Earth, consisting of a deep and wide hole in the ground and an equally sized cylinder of the excavated earth, the Mono-ha artist Sekine Nobuo affirmed:

“If you dig a hole in the earth and keep digging forever, (…) and if you go on to pull out all the earth, [the Earth] will be reversed into a negative version of itself.”Sekine Nobuo cited in Reconsidering Mono-ha, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2005, p. 74

The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923 and the ravages of war created successive scenes of destruction and contributed to a collective memory of ruins, used as evocative subject matter by Japanese painters and photographers to this day.

In the postwar period, reconstruction was not only political and economic, but also literal, in the urban and architectural sense. Modernism was adopted as the language of this reconstruction. The architect Tange Kenzo, who worked for Maekawa Kunio, one of Le Corbusier’s disciples, became one of the most consequential postwar modernists both as an architect and as an urban planner.

Tange’s unrealized “Plan for Tokyo 1960” heavily influenced the Metabolist movement, which Tange himself supported. Emblematic of Metabolism is the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Shinbashi, Tokyo, whose capsule-like rooms are prefabricated units meant to be replaced once they wore out. The “capsules” were designed as integral to a megastructure of both permanent and impermanent parts, built in the spirit of organic growth.

Metabolism is the name of a postwar architectural movement whose core ideas entailed a rapprochement between interconnected architectural structures and the principles and appearances of organic growth.

Heisei period (1989-2019)

Corresponding to the reign of emperor Akihito, the Heisei (literally, “achieving peace”) was a period of peace, but one that nonetheless witnessed economic stagnation and natural disasters. In the cultural sphere, the Heisei period saw the establishment of new art museums and the adoption of new means of expression among Japanese artists, although always in dialogue with the recent or more distant past.

Manga and anime exploded in popularity and influence during this period, although both have deep histories. Manga refers generally to comics and its roots harken back to medieval narrative picture scrolls. Anime refers, of course, to animation, which goes back to the early 20th century and includes, in Japan, the controversial history of its use as a propaganda tool during World War II. In the 1990s, the anime industry grew via revivals and sequels of popular 1970s productions as well as via new genres.

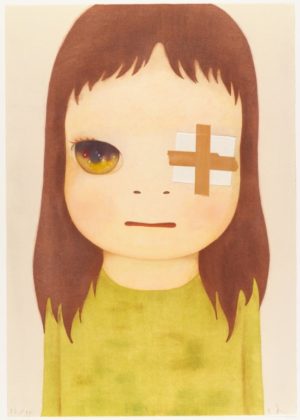

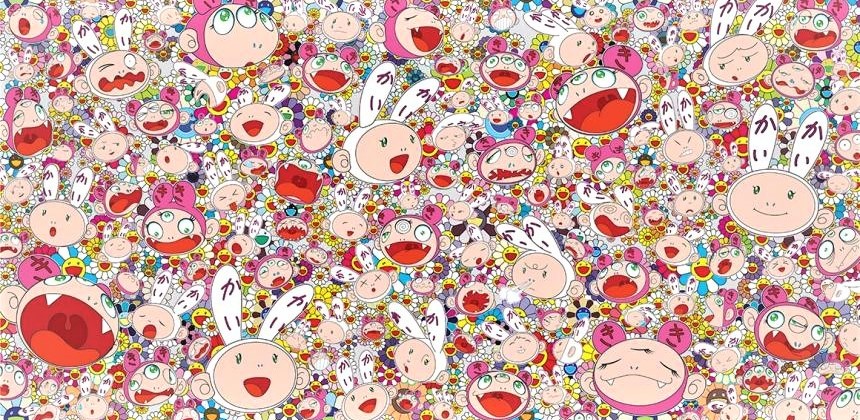

Popular both domestically and internationally, anime and manga are closely related to the principle of kawaii, translated as “cute.” This culture of “cuteness” has often been understood as a form of escapism from the harsh realities of the postwar period and of a country often threatened by calamitous natural disasters. Artists like Yoshitomo Nara and Murakami Takashi use elements from manga and anime to explore the darker underside of kawaii.

Artists like Murakami Takashi refer not only to the contemporaneous culture of manga and anime in their works, but also to older lineages and genealogies of Japanese art history. Murakami is a case in point with his personal and often provocative interpretations of Edo-period “eccentric” painters whose works nonetheless became integral to the canon of Japanese visual arts. Like Andy Warhol or more recently Jeff Koons, Murakami complements his works in painting, sculpture, and installation with merchandise and publications produced by his company, Kaikai Kiki.

Contemporary Japanese artists use a variety of mediums to express their vision or to focus on the perfection and re-invention of a medium. For example, Sugimoto Hiroshi has gained international acclaim for his contemplative photographs of seascapes as well as for his site-specific sculptural and architectural works. Mariko Mori epitomizes the multidisciplinary artist, exploring her sense of identity and developing her surreal imagery through photography, video, sculpture, installation, and performance. Distinct from artists like Sugimoto and Mori, many contemporary Japanese ceramists devote themselves exclusively to the materials and practices of ceramic art; and similar to artists like Murakami, they produce new works that both honor and challenge tradition.

As of May 1st, 2019, when emperor Akihito’s son, Naruhito, ascended the throne, we entered a new era for Japan, namely the Reiwa (translatable to “beautiful harmony”). In Japan as elsewhere, the art of today continues to resonate with the past, while carving its own path forward.

Additional resources

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

Japanese art: the formats of two-dimensional works

Japanese two-dimensional works of art can take a number of different formats—printed books (ehon), single- or multi-sheet prints (hanga), paintings in the form of hanging-scrolls (kakemono) and handscrolls (emaki), moveable folding screens (byōbu), usually in pairs, sliding door paintings (fusuma-e) and smaller scale fan paintings and album leaves. The screens and sliding doors also served to exclude draughts or divide rooms, and were changed according to the season. Hanging-scrolls were displayed, sometimes in pairs or sets of three in the tokonoma (ceremonial alcoves) of reception rooms of mansions and, again, could be changed according to the season, or to honor a special visitor. All such works were viewed seated at floor level on tatami mats.

Handscrolls (like the one above) were usually placed on a low table and unrolled from right to left to show a narrative story or seasonal sequence. Print series, small-scale paintings or fan paintings were often mounted in albums. Individual prints, especially the Ukiyo-e portraits of popular actors or courtesans, might be pasted to a screen. The size of the print was limited by the size of cherry-wood block available. Often two, three or more sheets were arranged side by side to depict a wider scene. Books were printed two pages to one sheet of paper, which was then folded, and the sheets sewn together at the spine with a plain cover.

Hanging Scrolls

Kakemono (hanging scrolls) were originally used to display Buddhist paintings, and calligraphy. The painting in ink and colors on either silk or paper was backed with paper and given silk borders chosen to harmonize with the painting. Finally, a roller was affixed to the bottom. Scrolls were kept in specially made paulownia wooden boxes to protect them from dust, changing climate conditions and insect damage.

Suggested readings:

L. Smith, V. Harris and T. Clark, Japanese art: masterpieces in The British Museum (London, The British Museum Press, 1990)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Kofun period (300-552 C.E.)

Haniwa Warrior

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Haniwa warrior in keiko armor (Kofun period), c. 6th century, excavated in lizuka-machi, Ota City, Gunma, Japan, terracotta, 130.5 cm high (Tokyo National Museum)

Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Funerary objects meant to be seen