5.5: Korea

- Page ID

- 67051

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Powerful kingdoms have ruled the Korean peninsula for millennia, creating luxurious art for the elite.

57 B.C.E. - present

Gold and jade crown, Silla Kingdom

All that glitters was gold in ancient Korea. In the fifth and sixth centuries, the Korean peninsula was divided between three rivaling kingdoms. The most powerful of these was the Silla kingdom in the southeast of the peninsula. Chinese emissaries described the kingdom as a country of gold, and perhaps they had seen its crowns adorned with shimmering gold and jade.

Although their fragile gold construction initially led some to believe that these crowns were made specifically for burial, recent research has revealed that they were also used in ceremonial rites of the Silla royalty during the Three Kingdoms Period (57 B.C.E. – 676 C.E.). Prior to the adoption of Buddhism, Koreans practiced shamanism, which is a kind of nature worship that requires the expertise of a priest-like figure, or shaman, who intercedes to alleviate problems facing the community. Silla royalty upheld shamanistic practices in ceremonial rites such as coronations and memorial services. In these sacred rituals, the gold crowns emphasized the power of the wearer through their precious materials and natural imagery.

Worn around the forehead, this tree-shaped crown (daegwan) is the headband type found in the south in royal tombs at the Silla capital, Gyeongju. Between the fifth and sixth centuries, Silla crowns became increasingly lavish with more ornamentation and additional, increasingly elongated branch-like protrusions. In this crown, three tree-shaped vertical elements evoke the sacred tree that once stood in the ritual precinct of Gyeongju. This sacred tree was conceived of as a “world tree,” or an axis mundi that connected heaven and earth. Two additional antler-shaped protrusions may refer to the reindeer that were native to the Eurasian steppe that lies to the north of the peninsula. Attached to the branch-like features of the crown are tiny gold discs and jade ornaments called gogok. These jade ornaments symbolize ripe fruits hanging from tree branches, representing fertility and abundance. With sunlight falling on its golden discs, the crown must have been a luminous sight indeed.

A second type of crown, the conical cap (mogwan), was found throughout the peninsula. Although it was initially thought to be an internal component of the headband crown, mural paintings show that it was worn independently over a topknot to proclaim the rank and social status of its wearer. The cap was secured to the head with double straps under the chin, as indicated by the small holes along either side of the cap. Appendages in the shape of wings, feathers, or flowers often were used to accessorize the crown, and those ornaments tended to be geographically specific to each kingdom.

Eurasian connections

The Silla crown demonstrates cultural interactions between the Korean peninsula and the Eurasian steppe (thousands of miles of grassland that stretches from central Europe through Asia). Scytho-Siberian peoples of the Eurasian steppe created golden diadems similar to the Silla crown, such as a crown from Tillya Tepe (an archaeological site of six nomad graves that contained objects known as the “Bactrian Hoard”) in modern-day Afghanistan. With five tree-shaped projections, flower ornaments and reflective discs, the Tillya Tepe crown can be compared with the natural imagery and radiant gold of the Silla crown. Though separated by many miles and by centuries, both crowns attest to shamanic beliefs prevalent among the nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe.

Burial customs in the Three Kingdoms Period

Though their use of gold and practice of shamanism related to the northern steppe cultures, the Silla royalty adopted the burial customs of the Chinese by burying their elite in mounded tombs. In Chinese burials, objects that were important in life were often taken to the grave. Similarly, power objects like the Silla gold crowns were used both above ground and below, and their luxurious materials conveyed the social status of the tomb occupant in the afterlife.

In addition to crowns, belts, earrings, other jewelry were placed in Korean tombs during the Three Kingdoms era to represent the rank and identity of the wearer. This gold belt, for instance, was made for the burial of a Silla king. It was like a tool belt or charm bracelet, with pendants that dangled from its band of interlinked square plates and entwining dragon openwork. Some objects were practical, such as knife sheaths and needle boxes, which evoked nomadic life on the Eurasian steppe. Others were symbolic, such as the comma-shaped ornaments seen on the Silla crown or miniature fish, which may have been charms to avert evil. The materials of the belt also corresponded to social status; for example, tombs of the Silla royalty had gold belts, while the nobility in other regions of the peninsula had silver or gilt-bronze belts.

Korea and the Silk Road

Stretching from the Mediterranean to the Silla kingdom at the tip of the Korean peninsula, the Silk Road connected a vast terrain of ancient cultures. While the Silla kingdom shared shamanism with the Eurasian steppe and burial customs with China and Japan, the Silk Road was a main route for conveying materials, techniques, and ideas from as far away as Rome. Luxury objects in tombs of the Silla elite, such as these earrings, are made of gold and decorated with stylized foliage that resembles the Silla crown. Two tiers of leaf-shaped ornaments dangle from double loops adorned with floral motifs, continuing the imagery of the sacred world tree.

However, a closer look at the thick, upper loop of each earring reveals the technique of granulation. Metalworking techniques, such as granulation (a technique whereby a surface is covered in spherules or granules of precious metal) and filigree—seen in the Mediterranean—appear to have traveled along the Silk Road. Silla tombs also contained other objects, such as Roman glass bowls and ewers, which reveal the extent to which luxury materials traveled via the Silk Road. These prized imports clearly inspired new forms of Korean-made luxury goods for use in both life and death.

Additional resources:

View the crown up close on the Google Art Project

View the conical cap up close on the Google Art Project

Soyoung Lee and Denise Patry Leidy, Silla: Korea’s Golden Kingdom, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2013.

“Silla: Korea’s Golden Kingdom” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Tomb construction animation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Silla Korea and the Silk Road: Golden Age, Golden Threads,” at the Korea Society

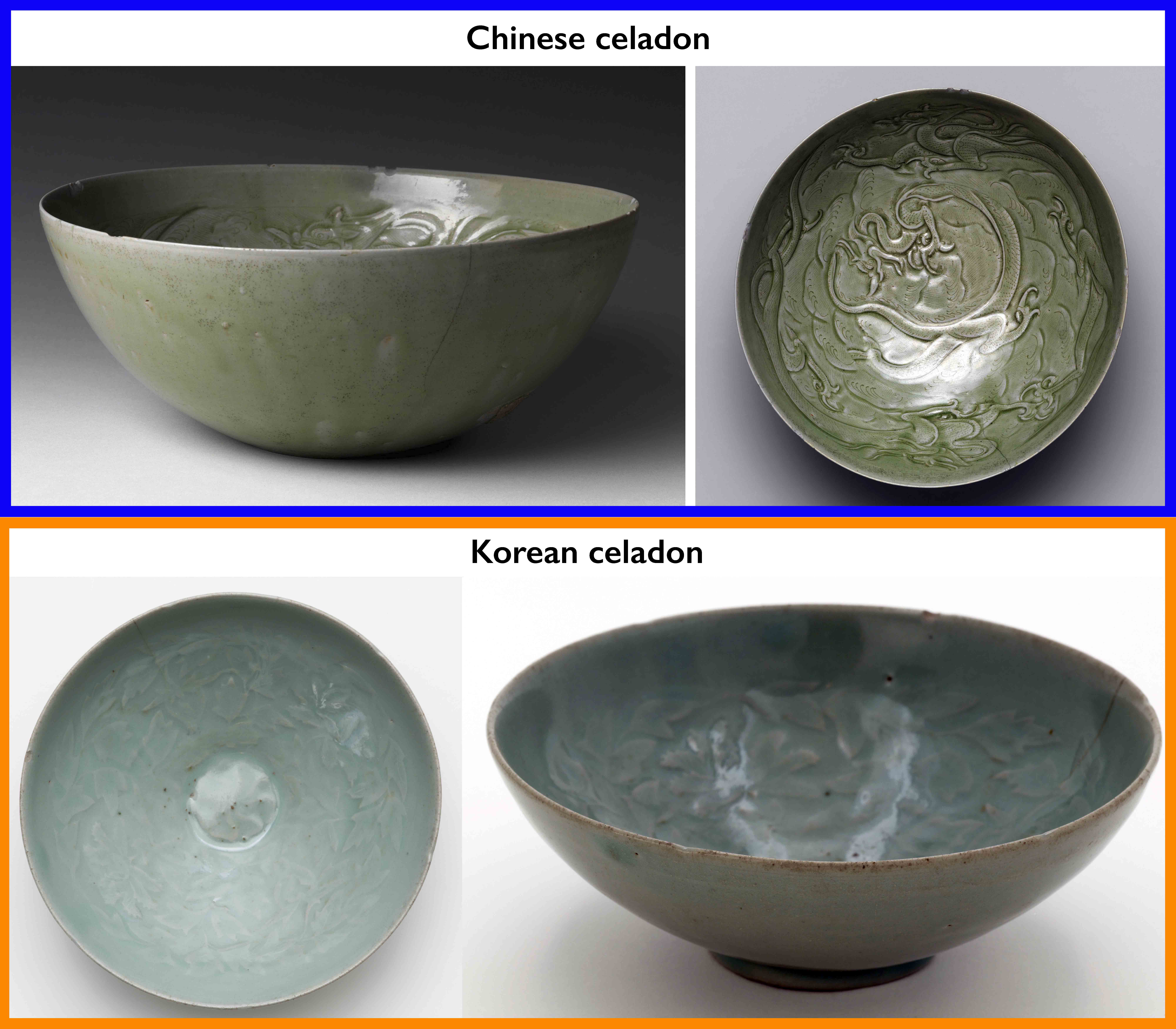

Korean Celadons of the Goryeo Dynasty

by SOL JUNG

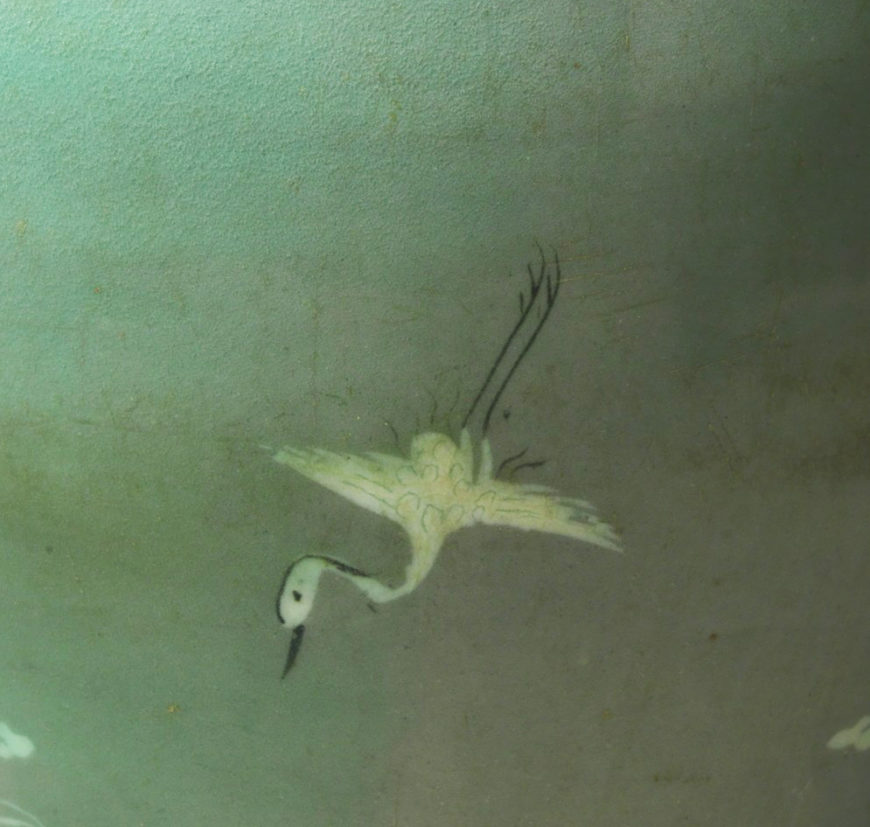

Cranes fly amongst floating clouds on the cool blue-green background of a curvaceous ceramic vessel. This object, called a maebyeong, is representative of Korean celadons made during the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). Celedons are ceramics with a distinctive green-blue glaze. The color, coupled with intricate inlaid ornamentation, are part of what has made Goryeo celadons desirable and recognizable objects for centuries. Korean potters adapted and refined celadon technology from China to create distinctively Korean ceramics revered by elites in Korea, China, and Japan alike. Many of the Korean celadons in museum collections, such as jars, bowls, and cups, were archaeological artifacts excavated from tombs and royal palaces. The combination of vibrant colors, delicate forms, and intricate decorative techniques contribute to the renown of Goryeo celadons as exemplary works of Korean art.

The Goryeo or Koryŏ Dynasty unified the Korean Peninsula and was a time of great artistic and cultural achievements. Koryŏ also gives its name to Korea.

Materiality, technique, and aesthetic

Archaeological evidence shows that Korean ceramic technology was advanced even before the Goryeo Dynasty. Korean stoneware from the Three Kingdoms Period (57 B.C.E.–676 C.E.) was fired at temperatures of 1000°C or higher, making it the earliest example of high-fired ceramics in the entire world. However, it was not until the Goryeo period that royal patronage focused on the production of a specific ceramic type, namely celadons.

Tenth-century Korean potters modified Chinese techniques to produce their own version of celadons. Potters used iron-rich clay to form the vessels and a glaze consisting of iron oxide, manganese oxide, and quartz particles. To achieve a consistent blue-green hue, Goryeo artisans developed a two-step firing process. The first step is bisque firing, which dries out and hardens unglazed vessels to make them stable and easier to handle. The second step involves firing glazed vessels in a low-oxygen “reducing” atmosphere to produce the desired celadon color and glossy texture.

Chinese potters fired their celadons in brick kilns, but Korean artisans used traditional mud kilns that effectively blocked the flow of oxygen to produce a brilliant celadon tone. Chinese celadons from the Yue kilns, for example, have a warmer olive green glaze compared to the cooler blue-green hue of Goryeo celadons. Achieving a uniform glaze color for celadons marked a shift in Korean ceramic production.

Form, color, and ornament became important factors in ceramic appreciation. Early Goryeo celadons emulated Chinese forms, but, gradually, Korean artisans developed their own aesthetic. Potters used molds to create ideal shapes and press popular patterns onto vessels. An incision technique adorned the clay surface with subtle linear designs, which were enhanced by the pooling of glaze in the grooves of varying depths. Flowers and birds were common motifs, particularly lotuses, peonies, parrots, waterfowl, and cranes. Goryeo celadons also featured painted underglaze elements; iron oxide fired to a black or brown, and copper oxide used for red. In rare instances, gold was applied over the celadon glaze to enhance underglaze designs.

Fanciful forms, such as melon-shaped ewers (or pitchers), and elaborate incense burners featuring latticed openwork, demonstrate the careful handiwork involved in making luxury celadons.

In the mid-twelfth century, Goryeo potters began using an inlay technique called sanggam to adorn celadons. Potters stamped or carved out a design, then filled it with white or black slip before the first bisque firing (slip is a mixture of clay, water, and typically a mineral pigment). The inlay on a maebyeong decorated with cranes and clouds best exemplifies this technique of sanggam. The potter used white slip to depict the cranes and clouds, adding intricate details such as feathers and curlicued wisps. The addition of black slip accentuates the crane’s form. Such inlaid creations, uncommon in China, became emblematic of a Goryeo ceramic aesthetic.

Royal patronage and maritime trade

Goryeo celadons adorned the lives of the elite. Potters fashioned celadons into tableware, such as bowls, plates, cups, and ewers, ritual implements, such as incense burners and kundika bottles, and decorative vessels, such as flower containers and cosmetic cases. Some monumental buildings even featured elaborate celadon tiles.

Kundika are ritual pitchers.

The Goryeo royal court heavily invested in celadon production and the development of its refined ornamentation. Archaeological evidence indicates that celadon production started in the Goryeo capital of Gaeseong in the second quarter of the tenth century. In the late eleventh to early thirteenth centuries, celadon kilns were re-established in Gangjin, located in today’s South Jeolla province.

Celadon kilns flourished in Gangjin: its ecological features provided material resources for ceramic production such as raw clay and firewood, and the geography offered a natural port where ships could dock to load cargo for transport. The strategic placement of Goryeo royal warehouses along the entire Korean coastline consolidated local goods from different districts to be sent yearly to the capital of Gaeseong as tax payment. Gangjin shipped large quantities of celadons to the capital for the royal court and and the nobility to display, gift, and use in their palaces. The structure of the flat-bottomed Goryeo ships allowed for stable, smooth sailing, especially when loaded with a cargo of heavy ceramics. Compared to bumpy travel over land, maritime travel facilitated the safe handling of large quantities of ceramics, keeping these valuable goods intact.

Goryeo celadons travelled across the sea to China and Japan. The 1976 excavation of the Shin’an shipwreck off Korea’s southwest coast unearthed a massive cargo of ceramics, coins, lacquerware, incense, and herbs. The ship departed from the Chinese port of Ningbo and was headed for Japan when it sank in 1323. Though the majority of excavated ceramics were Chinese, there were seven Goryeo celadon vessels on the ship specially selected for the Japanese market. Goryeo celadons have a substantive presence at medieval Japanese (1130–1600) archaeological sites, revealing that Buddhist monks, urban dwellers, military elites, and nobility enthusiastically collected these Korean ceramics.

Korean celadons in historical records

Historical accounts speak of Chinese appreciation for Goryeo celadons. The Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279) envoy, Xu Jing, visited the Goryeo capital, Gaeseong, in 1123. Xu noted the similarity of Goryeo celadons to ceramics at China’s famous Yue and Ru kilns. Xu expressed personal praise for Goryeo ceramics, stating that “those recently made show excellent craftsmanship and much improved color.” In a contemporaneous collection of writings, Brocade in the Sleeve (Xiuzhongjin), Song Dynasty author, Taiping Laoren, mentioned “jade-colored celadon of Goryeo” along with other luxury items as “the best under heaven” and “incomparable to any.” These records reveal how Chinese elites during the Song Dynasty acknowledged and admired the beauty of Korean celadon glazes.[1]

The History of Goryeo (Goryeosa) records a diplomatic episode where Kublai Khan examined a Goryeo gold-painted celadon vessel (the Mongol ruler had defeated the Chinese and established the Yuan Dynasty). He asked a Goryeo envoy, Jo Ingyu, if the gold strengthens the vessel. Jo replied no, explaining that it is merely decorative. Next, Kublai asked if the gold can be reused. When Jo answered no, Kublai demanded that such ceramics no longer be made. Since the Goryeo usually offered metal vessels to the Mongol khans as tribute, these rare gold-painted celadons were most likely exclusive gifts for the Mongol court. Though the Goryeo court wanted to impress Kublai, his disappointment at the wasteful use of precious gold reveals a clash between Mongol and Goryeo aesthetics. Nonetheless, Goryeo celadons remained a popular item among Mongol elites, and under Kublai’s rule, an active ceramics trade unfolded between Korea and China.

Goryeo potters successfully produced exquisite celadons, which gained recognition within East Asia as ceramics unique to Korea. Goryeo celadons are now iconic objects—they are the earliest Korean ceramics studied and appreciated for their aesthetic and art historical value, making them important objects to study today.

Notes:

[1] Namwon Jang, “Introduction and Development of Koryŏ Celadon,” in A Companion to Korean Art, eds., J.P. Park, Burglind Jungmann, and Juhyung Rhi (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley and Sons, 2020), pp. 144–145

Additional resources:

Cranes and Clouds: The Art of Korean Ceramic Inlay, National Museum of Asian Art

Lee, Soyoung. “Goryeo Celadon.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Jang, Namwon. “Introduction and Development of Goryeo Celadon,” in A Companion to Korean Art. Edited by J.P. Park, Burglind Jungmann, and Juhyung Rhi (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley and Sons, 2020), pp. 133–156.

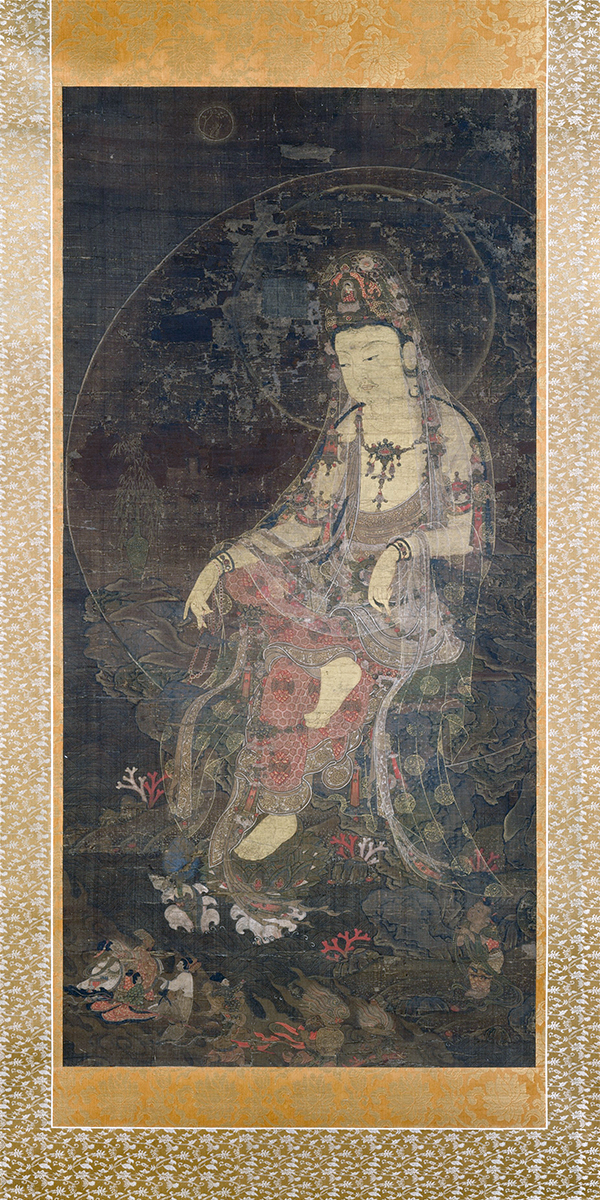

Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara

Goryeo Buddhist Painting

The term “Goryeo Buddhist Painting” refers to a group of Korean paintings, mostly from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, that depict Buddhist icons, typically in a format of large hanging scrolls. As Buddhism flourished as the official religion during the Goryeo dynasty, various Buddhist artworks were produced under royal patronage and used for state-sponsored ceremonies and funerary rituals. These paintings reflect not only the beliefs, but the taste and refinement of the Goryeo royalty and nobility.

The Goryeo dynasty ruled the Korean peninsula from 918 to 1392. The modern word “Korea” is derived from the name of this dynasty.

Pure Land Buddhism, focused on the Buddha Amitābha, is a branch of Mahayana Buddhism and one of the most widely practiced traditions of Buddhism in East Asia. It promises believers rebirth in Amitābha’s Western Paradise and enjoyed enormous popularity in Goryeo society. The Amitabha Buddha was typically portrayed either alone, in a triad, or flanked by the Eight Great Bodhisattvas. The bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Ksitigarbha were also widely worshipped in the Goryeo kingdom, and numerous scroll paintings attest to their popularity.

Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have chosen to stay on earth to help others achieve enlightenment. The Eight Great Bodhisattvas each represent a particular characteristic of the Buddha, such as wisdom or compassion.

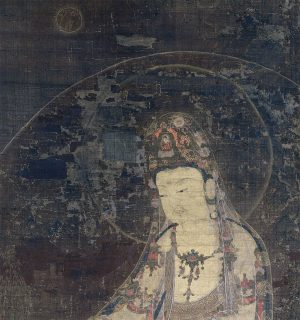

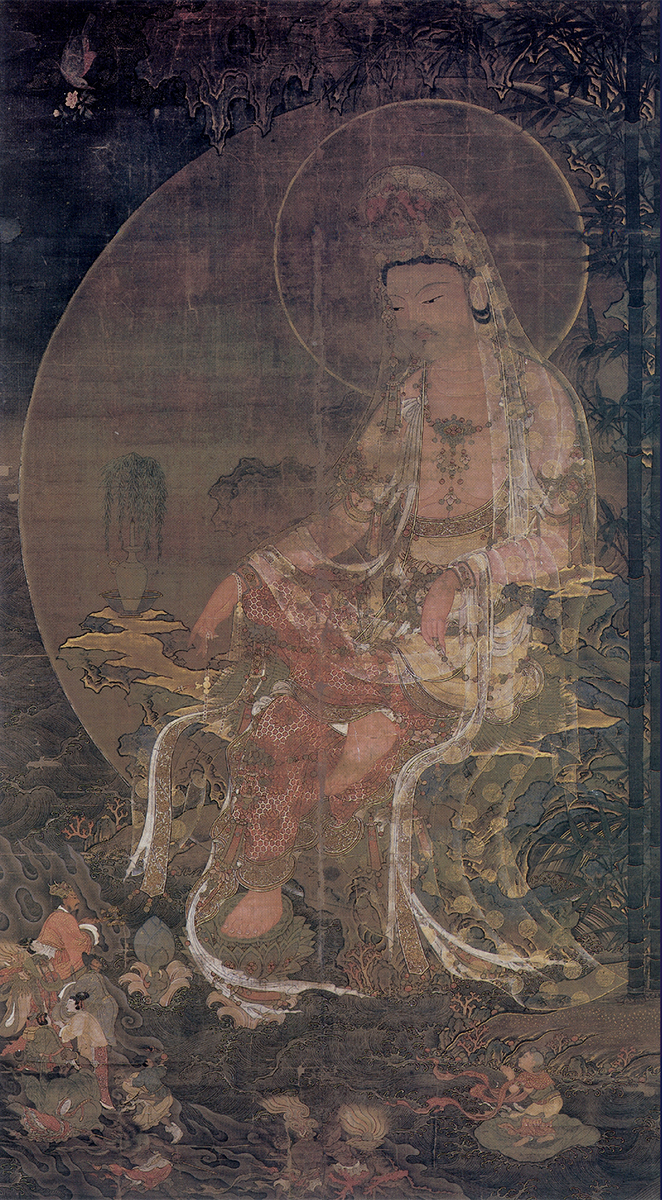

Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara

In this painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (above), the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara is depicted in typical Goryeo fashion as “Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara.” He is shown seated on a rocky outcrop protruding from the sea in his mountain-island abode, Mount Potalaka, where water flows from numerous springs and the landscape is populated by fragrant grass and flowers, marvelous trees, and coral. He sits with his right leg crossed and his left foot placed on a lotus-flower support, holding a crystal rosary in his hand. He is dressed in dazzling robes and sashes, with intricate gold details on his jewelry and clothing.

A rosary is string of beads used for prayer and chanting.

Goryeo Buddhist paintings are well known for their delicate details and sumptuous execution. They include exquisitely drawn garments created through the ample use of mineral pigments accented with gold, and illusionary effects seen in the depiction of transparent veils. Here, long transparent veils extend from Avalokiteśvara’s crown to the pond in the lower portion of the painting, adorned with patterns of white hemp leaves or white medallions filled with flower patterns and plant scroll designs. Two stalks of bamboo are depicted behind the rock where Avalokiteśvara is seated, and his body and head are surrounded by a large luminous mandorla and a nimbus, or halo, to represent his divinity. On the rock table to one side, we see a bronze or ceramic kundīka vessel with willow branches. In the lower right-hand corner of the painting, the boy pilgrim Sudhana, who travels to seek enlightenment and wisdom, appears in a pose of adoration.

Pigments are substances used in paint to give it a particular hue. They are often derived from minerals.

A mandorla is an oval shape that surrounds the entire figure.

Kundīka vessels are jars used for Buddhist ritual purposes.

Inviting the viewer in

Goryeo Buddhist paintings were made by applying color to both the front and back of the silk canvas. By working on the reverse side of the canvas, artists could create subtle effects, intensifying and contrasting with the primary colors painted on the front. Gold was extensively used to delineate figures and to accentuate the decorative patterns on robes and jewelry. The body was outlined with ink, while a thin red line was employed for the facial features.

In some paintings, a diminutive moon is depicted at the top, from which the name “Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara” originates. The willow tree motif may symbolize the cleansing and healing power of the deity, and is also closely related to Chinese Buddhist paintings of the Western Xia dynasty (1038-1227), which flourished around the same time. [1] However, there are also several notable features unique to Goryeo artworks.![]()

Goryeo Buddhist paintings frequently include secular and mythical figures, depicted as worshippers or patrons. They are often members of the royalty, aristocrats, or donors of paintings, wearing elegant court dress and elaborate hairdos decorated with jewelry and gold. These depictions allow us a glimpse into the taste for luxury and splendor amongst the ruling class in Goryeo society. For instance, in the painting of Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara held in the Daitoku-ji in Japan (above), a group of worshippers are depicted in the lower corner of this painting, kneeling and holding their hands together in a gesture of courtesy. They are identified as the mythical dragon king of the Eastern Sea, his queen, his royal entourage, and monsters bearing offerings of incense, coral, and pearls to the deity. Despite their small scale, these figures play an important role in the painting as well as the ritual context, acting as intermediaries between the secular and sacred worlds and inviting the viewer to the scene.

Tales from folklore

![]() Motifs from indigenous myths, miraculous stories, and folklore predating Buddhism were also incorporated in depictions of this deity to highlight his spiritual power. For instance, the blue bird, the dragon king, the rosary, and the pair of bamboo stalks in the Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara are related to stories about the famous Korean monks Ŭisang and Wonhyo and their miraculous encounters with Avalokiteśvara. A rabbit pounding the elixir of immortality under a laurel tree in the moonlight is another motif derived from a myth of ancient pre-Buddhist China, which tells of a rabbit (whose image can be seen on the face of the moon) who uses a mortar and pestle to prepare a life-giving potion for the Moon Goddess.

Motifs from indigenous myths, miraculous stories, and folklore predating Buddhism were also incorporated in depictions of this deity to highlight his spiritual power. For instance, the blue bird, the dragon king, the rosary, and the pair of bamboo stalks in the Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara are related to stories about the famous Korean monks Ŭisang and Wonhyo and their miraculous encounters with Avalokiteśvara. A rabbit pounding the elixir of immortality under a laurel tree in the moonlight is another motif derived from a myth of ancient pre-Buddhist China, which tells of a rabbit (whose image can be seen on the face of the moon) who uses a mortar and pestle to prepare a life-giving potion for the Moon Goddess.

Painted in vibrant colors of red, green, and blue with gold pigments, exquisite Goryeo Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara paintings represent the religious fervor of ardent believers in Pure Land Buddhism, as well as the splendid material culture of upper-class Goryeo society.

[1] It is not known for certain when or why the willow tree and the moon were included as standard features in Goryeo Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara paintings. Historical records indicate that the iconography of Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara, encircled by a full moon and seated in a bamboo grove, was invented by the famous Tang painter Zhou Fang (act.mid-ninth century). Although Zhou Fang’s painting does not exist any longer, the close affinities between similar works and Goryeo paintings suggest that the iconography of Goryeo Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara was based on that of Chinese precedents.

Portrait of Sin Sukju

Portrait paintings commemorated the sitter in both life and death in Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) Korea. This painting depicts Sin Sukju (1417-75) as a “meritorious subject,” or an official honored for his distinguished service at court and loyalty to the king during a tumultuous time. Skilled in capturing the likeness of the sitter while still adhering to pictorial conventions, artists in the Royal Bureau of Painting (a government agency staffed with artists) created portraits of officials awarded this honorary title. These paintings would be cherished by their families and worshiped for generations to follow.

The Joseon, or Yi dynasty, was founded in 1392 by the military leader Yi Song-gye and lasted until 1910. It was the last imperial dynasty and the longest in the history of Korea.

A meritorious portrait

This painting shows Sin Sukju dressed in his official robes with a black silk hat on his head. In accordance with Korean portraiture conventions, court artists pictured subjects like Sin Sukju seated in a full-length view, often with their heads turned slightly and only one ear showing. Crisp, angular lines and subtle gradations of color characterize the folds of his gown. Here, the subject is seated in a folding chair with cabriole-style arms, where the upper part is convex and the bottom part is concave. Leather shoes adorn his feet, which rest on an intricately carved wooden footstool. In proper decorum, his hands are folded neatly and concealed within his sleeves. He wears a rank badge on his chest.

Rank badges are insignia typically made of embroidered silk. They indicate the status of the official, which could be anyone from the emperor down to a local official. As in Ming-dynasty China (1368–1644), images of birds on rank badges precisely identified the rank of the wearer. Here, Sin Sukju’s rank badge shows a pair of peacocks amongst flowering plants and clouds. It is an auspicious scene suiting a civic official, and especially luminous with the use of gold embroidery. Crafted in sets, rank badges were worn on both the front and back of the official overcoat.

Physical likeness

Although portraiture conventions, such as the attire and posture of the sitter, were quite formulaic, the facial features were painted with the goal of transmitting a sense of unique, physical likeness. This careful attention to the sitter’s face, such as wrinkles and bone structure, served the Korean belief that the face could reveal important clues about the subject.

Look carefully and you might notice the wrinkles around the edges of Sin Sukju’s eyes (“crow’s feet”). His thin, almond-shaped eyes are bright and clear, and his mouth is surrounded by deep grooves where his moustache meets his chin. His solemn visage exudes wisdom and dignity.

The meticulous brushwork on Sin Sukju’s face is even more striking in comparison with the solid, undulating lines and bold blocks of color that define his attire. Highly skilled artists at the court may have collaborated on portraits, such that one artist may have painted the robes according to the prescribed rank or title, while another may have painted the face in great detail. Later portraits developed this interest in the face even further with the use of Western painting techniques introduced to Korea by Jesuit missionaries in China in the eighteenth century.

Sin Sukju and Hwagi

Sin Sukju was an eminent scholar and a powerful politician who rose to the rank of Prime Minister. Named a meritorious subject four times in his life, he served both King Sejong and King Sejo. Remarkably, he managed to maintain court favor through the tumult of King Sejo’s coup in 1453. In the course of capturing the throne, King Sejo arrested and killed his own brother, Prince Anpyeong, who Sin Sukju had also served until the prince’s untimely death.

It was his service to Prince Anpyeong that earned Sin Sukju a significant place in the history of art. In 1445, Sin Sukju compiled Hwagi (Commentaries on Painting), which contains a catalogue of Prince Anpyeong’s collection of paintings. Sin Sukju’s detailed records revealed the prince’s interest in Chinese paintings and his patronage of the Joseon court painter, An Gyeon, who was professionally active as an artist for 30 years beginning in approximately 1440. Sin Sukju’s commentaries have helped scholars to identify specific works and prompted speculation on the cultural exchange between China and Korea.

Ancestral worship

In addition to the virtue of loyalty (such as the devotion of a subject to his ruler), Confucianism emphasized filial piety, or honor and respect for one’s elders and ancestors. Even more important than recording the sitter’s appearance and preserving his rank during life, portrait painting served as a focus for ancestral rituals after his death. It was thought that when a person died, the soul of the deceased remained among the world of the living until it gradually dissipated. Rendered in the format of a hanging scroll, this painting likely hung within the family shrine to guide the soul in the practice of ancestral worship. In this way, Portrait of Sin Sukju reflected both the honor that Sin Sukju brought to his lineage as a meritorious official as well as Confucian beliefs about the afterlife.

Confucianism is named after Kong Qiu (later given the Latinized name Confucius) who lived from approximately 551 until 479 B.C.E. Confucianism is a philosophical system that stresses a moral and ethical order. the teachings of Kong Qiu have had an immense impact on Chinese culture for more than two millennium.

Additional resources:

Cho, Sunmie. “Joseon Dynasty Portraits of Meritorious Subjects,” Korea Journal 45, no. 2 (Summer 2005), pp. 151–85.

Jungmann, Burglind. “Sin Sukju’s Record on the Painting Collection of Prince Anpyeong and Early Joseon Antiquarianism,” Archives of Asian Art 61 (2011), pp. 107-126.

Lee, Soyoung, with essays by JaHyun Kim Haboush, Sunpyo Hong, and Chin-Sung Chang, Art of the Korean Renaissance, 1400-1600, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009

Song Su-Nam, Summer Trees

Modern, but deeply rooted in tradition

In Song Su-nam’s Summer Trees, broad, vertical parallel brush strokes of ink blend and bleed from one to the other in a stark palette of velvety blacks and diluted grays. The feathery edges of some reveal them to be pale washes applied to very wet paper, while the darkest appear as streaks that show both ink and paper were nearly dry. The forms overlap and stop just short of the bottom edge of the paper, suggesting a sense of shallow space—though one that would be difficult to enter. Only a practiced hand could control ink with such simplicity and impact. The painting exudes psychological power, despite its relatively modest proportions (it is only a little more than 2 feet high).

Song’s exploration of tone (the shades of black and gray) and the effects produced by the marks of the brush, the wet paper, and dripping ink, has led some to think that these abstract, formal qualities are the real subject of this very modern-looking work. But it is important that the title refers to the natural world. Song created Summer Treesin 1979, but he made at least two similar paintings. One, in 1986, he called Tree (below). Not until the second, painted in 2000, did he fully embrace abstraction by leaving the work untitled. His title—and even his decision to create a work in ink—shows us that though clearly addressing issues of contemporary art—Song’s work is deeply rooted in tradition.

Ink

To choose the medium of ink on paper was important for the artist‚ a leader of Korea’s “Sumukhwa” or Oriental Ink Movement of the 1980s. Sumukwha is the Korean pronunciation of the Chinese word for “ink wash painting,” also called “literati painting.” The “literatus” can be defined as a “scholar-poet” or “scholar-artist,” a type of ideal man that emerged in China in the eleventh century or before. Chinese poetry was considered the noblest art and “ink wash painting” was its twin, because writing a poem and making a painting used the same tools and techniques—one resulting in words, the other a picture. In their simplicity and reductiveness, the style of ink wash paintings created centuries ago often seem to match Western notions of abstraction (left).

In Chinese poetry, mountainous landscapes and the plants that grow in them serve as metaphors for the ideal qualities of the literatus himself—qualities such as loyalty, intelligence, spirituality, and strength in adversity. The world the literatus wants to live in is one of beauty, deep in nature, away from the centers of power and money. These themes provided painters with a library of motifs. From the 1970s–90s, Song created many such landscapes, executed unconventionally, with and without titles. Summer Trees may also reference a traditional theme: a group of pine trees can symbolize a gathering of friends of upright character. Whatever his intention with this title, Song was clearly alluding to the special world of the literati. Highly educated and a respected professor, he stood among the modern literati of Korea.

A Korean identity

Song’s interest in abstraction and the formal properties of ink has led some art historians to attribute the inspiration for his work to that of American artists like Morris Louis who used the medium of acrylic resin on canvas in his “Stripe” paintings of the 1960s, which resemble Song’s works of later decades such as Summer Trees. But in Korea during the 1980s there was a tension between the influence of Western art that used oil paint (whether traditional or contemporary in style), and traditional Korean art that used an East Asian style, the vocabulary of traditional motifs, and the medium of ink for calligraphy and painting. Song felt very strongly that the materials and styles of Western art did not express his identity as a Korean.

Sumukwha provided Song and his circle with a way to express Korean identity. Since antiquity, the country had taken great pride in a political and cultural distinctiveness that was recognized throughout Asia. Yet the twentieth century had brought humiliating trauma: the end of Korea’s ancient monarchy, colonization by the Japanese who had attempted to obliterate the Korean language, mass destruction during the Korean War (1950-53), and the partitioning of the nation. In South Korea, where Song lived, the country was healing but endured authoritarian government and student unrest. People lived in constant fear of hostility from North Korea. For protection, they accepted a conspicuous American military presence, but this cast modernization in a decidedly Westernized light.

Sumukwha’s ideal—the literatus—presented a compelling antidote to the psychological displacement felt by Song’s circle of artists and intellectuals: a model individual of character and moral compass no matter what challenges life presents; and a way of expressing those ideals through his iconic tools of ink and brush. Summer Trees, with its allusions to friendship and a balmy season, could be Song’s statement of optimism in the rediscovery of traditional values recast for modern times.

Additional resources:

Song’s work at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Special Exhibition of Donated Works: Song Soo-nam at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Kim Seong-Heui, translated by Seung Il Oh, “On the Basis of Art Educational Implications”

Joan Kee, “The Curious Case of Contemporary Ink Painting” Art Journal, vol. 69, no. 3, 2010, pp. 88 – 113.

Lee Kyeung-sung. “Song Su-nam: The Ink Images Expanding Into Infinity,” exhibition of Song Su-nam, Center for Korean Studies, University of Hawaii, March 1 – 17, 1980.

Francis Mullany, Symbolism in Korean Brush Painting (Kent: Global Oriental 2006)

Jane Portal, Korea, Art and Archaeology (London: The British Museum Press, 2000)