5.3: China

- Page ID

- 67049

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)From prehistoric jade to contemporary political art — the art of China engages and challenges.

c. 3500 B.C.E. - present

A beginner's guide

Imperial China, an introduction

Imperial Chinese history is marked by the rise and fall of many dynasties and occasional periods of disunity, but overall the age was remarkably stable and marked by a sophisticated governing system that included the concept of a meritocracy. Each dynasty had its own distinct characteristics and in many eras encounters with foreign cultural and political influences through territorial expansion and waves of immigration also brought new stimulus to China. China had a highly literate society that greatly valued poetry and brush-written calligraphy, which, along with painting, were called the Three Perfections, reflecting the esteemed position of the arts in Chinese life. Imperial China produced many technological advancements that have enriched the world, including paper and porcelain.

Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism

Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism were the dominant teachings or religions in Imperial China and most individuals combined all three in their daily lives. Each of these teachings is represented by paintings in The British Museum, most notably by The Admonitions Scroll after Gu Kaizhi (image above) and the cache of Buddhist scroll paintings from the eighth to tenth century that had been rolled up and sealed away in the eleventh century in Cave 17 at Dunhuang’s Caves of the Thousand Buddhas (discussed in this tutorial).

© Trustees of the British Museum

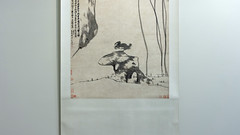

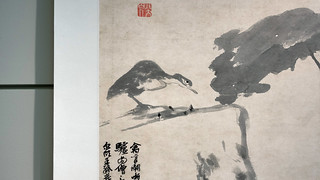

Chinese landscape painting

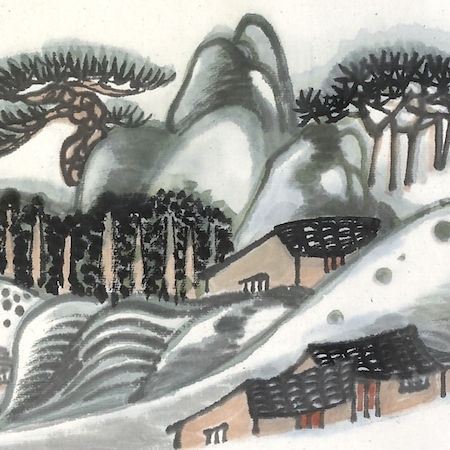

Landscape painting is traditionally at the top of the hierarchy of Chinese painting styles. It is very popular and is associated with refined scholarly taste. The Chinese term for “landscape” is made up of two characters meaning “mountains and water.” It is linked with the philosophy of Daoism, which emphasizes harmony with the natural world.

Idealized landscapes

Chinese artists do not usually paint real places but imaginary, idealized landscapes. The Chinese phrase woyou expresses this idea of “wandering while lying down.” In China, mountains are associated with religion because they reach up towards the heavens. People therefore believe that looking at paintings of mountains is good for the soul.

Chinese painting in general is seen as an extension of calligraphy and uses the same brushstrokes. The colors are restrained and subtle and the paintings are usually created in ink on paper, with a small amount of watercolor. They are not framed or glazed but mounted on silk in different formats such as hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves and fan paintings.

The scholar’s desk

In China, painters and calligraphers were traditionally scholars. The four basic pieces of equipment they used are called the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio or wenfangsibao: paper, brush, ink and inkstone. A cake of ink is ground against the surface of the inkstone and water is gradually dropped from a water dropper, gathering in a well at one end of the stone. The brush is then dipped into the well and the depth of intensity of the ink depends on the wetness or dryness of the brush and the amount of water in the ink.

Ink cakes were made from carbonized pinewood, oil and glue, moulded into cakes or sticks and dried. The most prized inkstones were made of Duan stone from Guangdong province, although the one shown here is made of ceramic. Brushes had very pliable hairs, usually made from deer, goat, wolf or hare. Wrist rests gave essential support while painting details. Other equipment used on a scholar’s desk includes brush washers, seals, seal paste boxes, brush pots and brush stands.

In the seventeenth century print-painting manuals began to be designed to help train artists. These showed, step by step, how to paint in the style of particular artists. They illustrated a variety of subjects, from small rocks to mountains or tree branches to forests. The different brush strokes were named and explained.

The earliest landscapes

In China, the earliest landscapes were portrayed in three-dimensional form. Examples include mountain-shaped incense burners made of bronze or ceramic, produced as early as the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.). The earliest paintings date from the sixth century. Before the tenth century, the main subject was usually the human figure.

In the period following the Han dynasty, Buddhism spread across China. Artists began to illustrate stories of the life of the Buddha on earth and to create paradise paintings. In the background of some of these brightly colored Buddhist paintings, it is possible to see examples of early landscape painting.

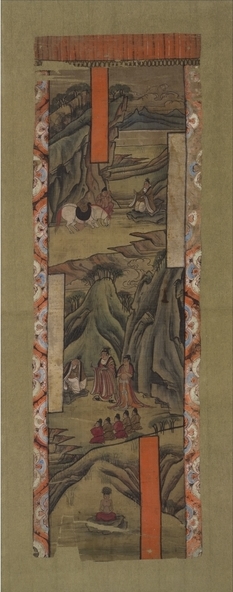

This scene is one of a series of three representing the life of the historical Buddha, Prince Sakyamuni, when he lived on earth. The mountains are simple triangles and their ridges are painted with short brush strokes to create texture. The water in the river is portrayed in a bold, diagrammatic way, conveying a sense of movement.

Chinese paintings are usually created in ink on paper and then mounted on silk. This is done using different formats including hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves and fan paintings.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Chinese porcelain: decoration

Chinese porcelain decoration: underglaze blue and red

Though Chinese potters developed underglaze red decoration during the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368 C.E.), pottery decorated in underglaze blue was produced in far greater quantities, due to the high demand from Asia and the Islamic countries of the Near and Middle East. Painting with underglaze red was more difficult than underglaze blue: the copper oxide used as the coloring agent was harder to control than the cobalt that was used for the underglaze blue. The firing left parts of the red areas grey, as on this large jar (above).

The first emperor of the Ming dynasty, which was to rule China for the next 300 years, was the general Zhu Yuanzhang (reigned 1368-98), whose title was Hongwu. He overthrew the Yuan dynasty, whose rulers had been foreigners (Mongols). He was determined to re-establish the dominance of Chinese style at court, and blue-and-white porcelain was produced in designs following Chinese rather than Islamic taste. Similar pieces were executed with underglaze red for use by the emperor.

Hongwu banned foreign trade several times, though this was never fully effective. The import of cobalt was disrupted, however, which resulted in a drop in the production of blue-and-white porcelain. For a short time at the end of the fourteenth century, more wares were decorated with underglaze red than underglaze blue.

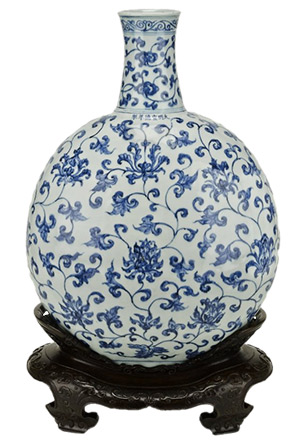

Blue-and-white porcelain

The earliest blue-and-white ware found to date are temple vases inscribed 1351. These display a competence which indicate that the underglaze-painting technique was well-established by that time, probably originating in the second quarter of the fourteenth century. Cobalt blue was imported from Iran, probably in cake form. It was ground into a pigment, which was painted directly onto the leather-hard porcelain body. The piece was then glazed and fired. “Blue-and-white” porcelain was used in temples and occasionally in burials within China, but most of the products of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) appear to have been exported.

Trade remained an essential part of blue-and-white porcelain production in the Ming and Qing dynasties (1644-1911). Europe, Japan and South-east Asia were important export markets. Vessels, with numerous bands of decoration, were painted with Chinese motifs, such as dragons, waves and floral scrolls. The potters of Jingdezhen also produced wares to satisfy the demands of the Middle Eastern market. Large dishes were densely decorated with geometric patterns inspired by Islamic metalwork or architectural decoration.

Blue-and-white porcelain was particularly admired by the Imperial court, and it is interesting to trace the shapes and motifs preferred by different emperors, many of whom ordered huge quantities of porcelain from the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen.

The blue-and-white wares of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries often took their shapes from Islamic metalwork. The globular body, tall cylindrical neck and dragon handle of this jug all imitate contemporary metalwork of Timurid Persia. The crowded decoration of this jug is a feature of early blue-and-white porcelain that continued into the early part of the Ming dynasty. It is very different to the generally more subtle character of Chinese ornament. The motifs used in decorating the jug, however, are still distinctly Chinese, notably the breaking waves on the neck and floral scroll on the body.

Overglaze enamels

The term “overglaze enamels” is used to describe enamel decoration on the surface of a glaze which has already been fired. Once painted, the piece would be fired a second time, usually at a lower temperature.

The first use of overglaze enameling is found on the slip-covered wares of northern China. This was an innovation of the Jin dynasty (1115-1234), with documented pieces as early as 1201. These were utilitarian wares, not for imperial use. Under the emperors of the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911) dynasty, the various techniques of overglaze enameling reached their heights at the manufacturing centre in Jingdezhen.

The most highly prized technique is known as doucai (“joined” or “contrasted” colors), first produced under the Ming emperor Xuande (1426-35), but more usually associated with Chenghua (1465-87). Cobalt was used under the glaze to paint the outlines and areas of blue wash needed in the design. The piece was then glazed and fired at a high temperature. Overglaze colors were painted on to fill in the design. The piece was then fired again at a lower temperature. The vase above, which dates to the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (C.E. 1723-35), is a very good example of the technical perfection in later doucai wares. The main design comprises green, yellow and mauve dragon medallions. The dragons are five-clawed, whose use was restricted to the emperor. Auspicious Buddhist emblems decorate the shoulder of the vase.

New colors (including pink!)

There were also important developments under the Qing dynasty. Famille rose (pink), jaune (yellow), noire (black) and verte (green) were overglaze enamel-decorated porcelains made from the Kangxi period (1662-1722) and later.

Accordingly to Chinese tradition, butterflies are an auspicious sign. They convey a wish for longevity, and were therefore often used to decorate birthday gifts or lanterns given during the Autumn Moon Festival: on the 15th day of the 8th month of the lunar calendar (usually around September). The Festival is celebrated by lighting lanterns of different shapes, sizes and colors, and by gazing at the moon. The bowl above, made at the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, may have been presented by the emperor to a family member or worthy subject on such an occasion.

The bowl is decorated in famille rose overglaze enamels. This technique was perfected under the Yongzheng emperor (reigned 1723-35) and is considered the last major technological breakthrough at the Jingdezhen kilns. The great innovation was the production of the distinctive pink enamel from which the wares take their name. The pink color was provided by adding a very small amount of gold to red pigment. The resulting color was opaque, as were the other famille rose enamels, and so could be mixed to create a wider range of colors than had been possible before.

Suggested readings:

S.J. Vainker, Chinese pottery and porcelain: From Prehistory to the Present (London, The British Museum Press, 1991).

Regina Krahl and Jessica Harrison-Hall, Chinese Ceramics: Highlights of the Sir Percival David Collection (British Museum Press, 2009).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Chinese porcelain: production and export

Porcelain was first produced in China around 600 C.E. The skillful transformation of ordinary clay into beautiful objects has captivated the imagination of people throughout history and across the globe. Chinese ceramics, by far the most advanced in the world, were made for the imperial court, the domestic market, or for export.

What is porcelain?

The Chinese use the word ci to mean either porcelain or stoneware, not distinguishing between the two. In the West, porcelain usually refers to high-fired (about 1300º) white ceramics, whose bodies are translucent and make a ringing sound when struck. Stoneware is a tougher, non-translucent material, fired to a lower temperature (1100-1250º).

A number of white ceramics were made in China, several of which might be termed porcelain. The northern porcelains, such as Ding ware, were made predominantly of clay rich in kaolin. In southern China, porcelain stone was the main material. At the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, kaolin was added to porcelain stone; in Fujian province, on the coast and east of Jiangxi, porcelain stone was used alone. The results differed in that northern porcelains were more dense and compact, while southern porcelains were more glassy and “sugary.”

Ceramics may be fired in oxidizing or reducing conditions (increasing or restricting the amount of oxygen during the process). Northern porcelains were usually fired in oxidation, which results in warm, ivory-colored glazes. Southern wares were fired in reduction, producing a cool, bluish tinge. An exception to this was blanc de Chine, or Dehua ware, from Fujian province, whose warm ivory hue came from oxidizing firings.

The export market

Chinese ceramics were first exported in large quantities during the Song dynasty (960-1279). The government supported this as an important source of revenue. Early in the period, ports were established in Guangzhou (Canton), Quanzhou, Hangzhou and Ningbo to facilitate commercial activity.

The ceramics trade established in the Song dynasty was maintained throughout the succeeding Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and with a few interruptions, the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties as well. The markets were concentrated in different regions at different times, but the global influence of China’s porcelains has been sustained throughout. Within Asia, up until the fourteenth century, the potters of Korea imitated China’s porcelain with considerable success, and Japan’s potters did so for a still longer period. In the Middle East, the twelfth-century attempts to reproduce Chinese wares went on throughout the Ming period. In Europe however, porcelain was barely known before the seventeenth century. The English and Germans produced mass quantities of a similar hard-bodied ware in the eighteenth century.

Chinese porcelain influenced the ceramics of importing countries, and was in turn, influenced by them. For example, importers commissioned certain shapes and designs, and many more were developed specifically for foreign markets; these often found their way in to the repertory of Chinese domestic items. In this way, Chinese ceramics were a vehicle for the worldwide exchange of ornamental styles.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Neolithic China

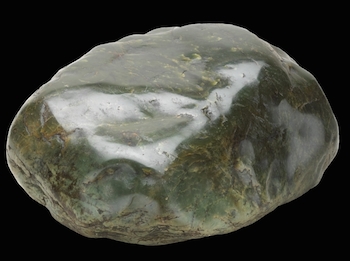

Jade has always been the material most highly prized in China, above silver and gold. From ancient times, this translucent stone has been worked into ornaments, ceremonial weapons and ritual objects.

c. 3500 - 1600 B.C.E.

Chinese jade: an introduction

What is jade?

The English term “jade” is used to translate the Chinese word yu, which in fact refers to a number of minerals including nephrite, jadeite, serpentine and bowenite, while jade refers only to nephrite and jadeite.

Chemically, nephrite is a calcium magnesium silicate and is white in color. However, the presence of copper, chromium and iron produces colors ranging from subtle grey-greens to brilliant yellows and reds. Jadeite, which was very rarely used in China before the eighteenth century, is a silicate of sodium and magnesium and comes in a wider variety of colors than nephrite.

Nephrite is found in metamorphic rocks in mountains. As the rocks weather, the boulders of nephrite break off and are washed down to the foot of the mountain, from where they are retrieved. From the Han period (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.) jade was obtained from the oasis region of Khotan on the Silk Route. The oasis lies about 5000 miles from the areas where jade was first worked in the Hongshan (in Inner Mongolia) and the Liangzhu cultures (near Shanghai) about 3000 years before. It is likely that sources much nearer to those centers were known about in early periods and were subsequently exhausted.

Worn by kings and nobles in life and death

“Soft, smooth and glossy, it appeared to them like benevolence; fine, compact and strong – like intelligence” —attributed to Confucius (about 551-479 B.C.E.)

Jade has always been the material most highly prized by the Chinese, above silver and gold. From ancient times, this extremely tough translucent stone has been worked into ornaments, ceremonial weapons and ritual objects. Recent archaeological finds in many parts of China have revealed not only the antiquity of the skill of jade carving, but also the extraordinary levels of development it achieved at a very early date.

Jade was worn by kings and nobles and after death placed with them in the tomb. As a result, the material became associated with royalty and high status. It also came to be regarded as powerful in death, protecting the body from decay. In later times these magical properties were perhaps less explicitly recognized, jade being valued more for its use in exquisite ornaments and vessels, and for its links with antiquity. In the Ming and Qing periods ancient jade shapes and decorative patterns were often copied, thereby bringing the associations of the distant past to the Chinese peoples of later times.

The subtle variety of colors and textures of this exotic stone can be seen, as well as the many different types of carving, ranging from long, smooth Neolithic blades to later plaques, ornaments, dragons, animal and human sculpture.

Neolithic jade: Hongshan culture

It was long believed that Chinese civilization began in the Yellow River valley, but we now know that there were many earlier cultures both to the north and south of this area. From about 3800–2700 B.C.E. a group of Neolithic peoples known now as the Hongshan culture lived in the far north-east, in what is today Liaoning province and Inner Mongolia. The Hongshan were a sophisticated society that built impressive ceremonial sites. Jade was obviously highly valued by the Hongshan; artifacts made of jade were sometimes the only items placed in tombs along with the body of the deceased.

Major types of jade of this period include discs with holes and hoof-shaped objects that may have been ornaments worn in the hair. This coiled dragon is an example of another important shape, today known as a “pig-dragon,” which may have been derived from the slit ring, or jue. Many jade artifacts that survive from this period were used as pendants and some seem to have been attached to clothing or to the body.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Jade Cong

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Jade Cong, c. 2500 B.C.E., Liangzhu culture, Neolithic period, China (The British Museum). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Ancient China includes the Neolithic period (10,000 -2,000 B.C.E.), the Shang dynasty (c. 1500-1050 B.C.E.) and the Zhou dynasty (1050-221 B.C.E.). Each age was distinct, but common to each period were grand burials for the elite from which a wealth of objects have been excavated.

The Neolithic Period, defined as the age before the use of metal, witnessed a transition from a nomadic existence to one of settled farming. People made different pottery and stone tools in their regional communities. Stone workers employed jade to make prestigious, beautifully polished versions of utilitarian stone tools, such as axes, and also to make implements with possible ceremonial or protective functions. The status of jade continues throughout Chinese history. Pottery also reached a high level with the introduction of the potter’s wheel.

Neolithic Liangzhu culture

A group of Neolithic peoples grouped today as the Liangzhu culture lived in the Jiangsu province of China during the third millennium B.C.E. Their jades, ceramics and stone tools were highly sophisticated.

Cong

They used two distinct types of ritual jade objects: a disc, later known as a bi, and a tube, later known as a cong. The main types of cong have a square outer section around a circular inner part, and a circular hole, though jades of a bracelet shape also display some of the characteristics of cong. They clearly had great significance, but despite the many theories the meaning and purpose of bi and cong remain a mystery. They were buried in large numbers: one tomb alone had 25 bi and 33 cong. Spectacular examples have been found at all the major archaeological sites.

The principal decoration on cong of the Liangzhu period was the face pattern, which may refer to spirits or deities. On the square-sectioned pieces, like the examples here, the face pattern is placed across the corners, whereas on the bracelet form it appears in square panels. These faces are derived from a combination of a man-like figure and a mysterious beast.

Cong are among the most impressive yet most enigmatic of all ancient Chinese jade artifacts. Their function and meaning are completely unknown. Although they were made at many stages of the Neolithic and early historic period, the origin of the cong in the Neolithic cultures of south-east China has only been recognized in the last thirty years.

Cong were extremely difficult and time-consuming to produce. As jade cannot be split like other stones, it must be worked with a hard abrasive sand. This one is exceptionally long and may have been particularly important in its time.

Bi

Stone rings were being made by the peoples of eastern China as early as the fifth millennium B.C.E. Jade discs have been found carefully laid on the bodies of the dead in tombs of the Hongshan culture (about 3800-2700 B.C.E.), a practice which was continued by later Neolithic cultures. Large and heavy jade discs such as this example, appear to have been an innovation of the Liangzhu culture (about 3000-2000 B.C.E.), although they are not found in all major Liangzhu tombs. The term bi is applied to wide discs with proportionately small central holes.

The most finely carved discs or bi of the best stone (like the example above) were placed in prominent positions, often near the stomach and the chest of the deceased. Other bi were aligned with the body. Where large numbers of discs are found, usually in small piles, they tend to be rather coarse, made of stone of inferior quality that has been worked in a cursory way.

We do not know what the true significance of these discs was, but they must have had an important ritual function as part of the burial. This is an exceptionally fine example, because the two faces are very highly polished.

Suggested readings:

J. Rawson, Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing (London, The British Museum Press, 1995, reprinted 2002).

J. Rawson (ed.), The British Museum book of Chinese Art (London, The British Museum Press, 1992).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Working jade

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. This video explores the significance and working of jade in China.

Shang dynasty (c.1600-1046 B.C.E.)

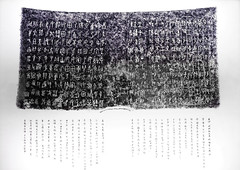

Oracle Bone, Shang Dynasty

by DR. KRISTEN CHIEM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Speakers: Dr. Kristen Chiem and Dr. Beth Harris

Cite this page as: Dr. Kristen Chiem and Dr. Beth Harris, "Oracle Bone, Shang Dynasty," in Smarthistory, October 8, 2016, accessed September 2, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/oracle-bone/.

Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 B.C.E.)

Da Ke Ding

by DR. KRISTEN CHIEM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Da Ke Ding, c. 1046 – 771 B.C.E. (late Western Zhou dynasty, China), bronze, 93.1 cm high (Shanghai Museum)

Speakers: Dr. Kristen Chiem and Dr. Beth Harris

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Eastern Zhou dynasty (770–256 B.C.E.)

Ambition and luxury: Marquis Yi of the Zeng State

by DR. KENT CAO

Imagine stumbling upon an undisturbed tomb filled with 15,000 items—from hundreds of jade and golden objects and enormous bronze wine vessels to massive lacquered coffins and a vast assortment of musical instruments. In 1978 in Leigudun, Suizhou, Hubei province, local military construction accidentally discovered such a luxurious tomb, one that was meant to impress. With all its contents still intact, this tomb (dating to the 5th century B.C.E during the Bronze Age) offers us a glimpse into how early burial customs and practices could not only reflect someone’s ambition, but also elevate their status.

The Bronze Age in China spans from the seventeenth century B.C.E. to the third century B.C.E.

Extensive bronze inscriptions suggest that the tomb owner was the Marquis Yi, who passed away in 433 B.C.E. or slightly later. He was of the Zeng state, a small southern state little known in the traditional historical record. Marquis Yi was active in the early Warring States period (481–221 B.C.E.), which witnessed the dissolution of the kin-shaped political system. Lords paid increasingly less respect to the nominal Zhou king, and they engaged in warfare against each other and competed for higher status and prestige.

The Warring States period is the second half of the Eastern Zhou period (770–256 B.C.E.).

The kings of the Zhou court were not able to effectively control the vast territory under their name. Therefore, the Zhou kings delegated land and populations to their sons, cousins, marital relatives and sometimes non-kin allies to establish vassal states. These states enjoyed political, taxational, and judicial autonomy while remaining politically and ritually subordinate to the king and assuming military and tributary obligations to the central court.

Despite the turbulence of this era, the luxurious furnishings from Marquis’s tomb with its overt display of wealth and power clearly reflect his ambition. The number of bronzes from his tomb is unmatched by any other burials in pre-imperial China. He was also buried with a number of ritual bronze vessels normally reserved for the Zhou kings, further implying the marquis’s interest in attaining a more prominent status. Because most of the princely burials in the Warring States period have been looted, the integrity and wealth of Marquis Yi’s tomb offers a rare opportunity to examine the elite culture and funerary customs in the late first millennium B.C.E.

Pre-imperial China is a historical concept that predates the establishment of the Qin Empire (221–207 B.C.E.). The Qin Empire was the first empire in the history of China. One of the most prominent transformations that brought forth by the Qin was the replacement of the kinship-based government with a centralized bureaucratic system.

Tomb Structure

The tomb of Marquis Yi was originally more than 40 feet below surface level, with layers of charcoal, viscous, and dry soil piled on to it to protect it. It is one of the earliest examples in ancient China that demonstrates the desire to replicate aboveground living quarters in funerary practice. This practice was an attempt to sustain a person’s secular privileges and pleasures in the afterlife. Inside, the tomb is divided into four compartments, each with a different designated function and associated objects. Here is a basic list of what was found:

Central chamber: extensive bronze ritual vessels and musical instruments for grand ancestral offering ceremonies and court banquets

North chamber: Chariot fittings and weapons such as bows, ge-halberds, shields, and armor

Ge-halberds are blades horizontally mounted onto the top of spears. They were the primary weapons used by foot soldiers.

East chamber: Marquis Yi’s main coffins surrounded by eight smaller coffins found with female human sacrifice victims and a coffin for a dog

West chamber: additional thirteen female human sacrifice victims.

The female victims in the tomb were approximately twenty years old, and were likely Marquis’s maids, musicians, and dancers. All these furnishings and the human entourage ensured that Marquis Yi would continue his sumptuous elite life after his death.

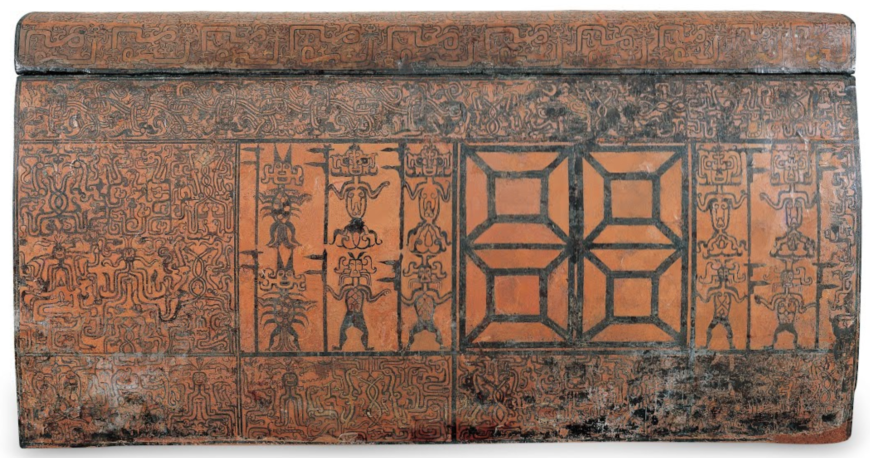

Double coffins

Outer coffin

Marquis Yi rested in enormous double coffins, which are impressive for their sheer size, intricate patterns, and bright lacquer. The outer coffin is an enormous rectangular box. This exceptionally large wooden box even has a bronze framework to stabilize it. It has a black lacquer background, and is decorated with yellow and red intertwined serpents surrounding a central swirl. Abstract cloud motifs fill the border between the main units.

Inner coffin

The inner coffin is considerably smaller in size, allowing its makers to construct it solely from wooden panels. Entangled serpents, birds, fish, and other composite animals decorate the surface. Spiritual beings in semi-animal form with weapons in hand also stand guard.

Both coffins

A series of designs on both coffins facilitated the spirit of Marquis Yi to travel freely and continue to enjoy his unparalleled luxury in the afterlife. The Zeng craftsmen painted windows on the inner coffin. They also carved out a square hole on the lower right corner on the north end of the outer coffin. Similar square openings on the bottom of the tomb’s wooden walls further enable access to all the chambers. Marquis Yi could ride his chariot in the north chamber for an outing and hold a sumptuous royal banquet in his central chamber.

Lacquer production was costly and time consuming. Craftsmen extracted lacquer from the toxic sap of the lacquer tree that is indigenous to China. The hazardous production process and the time-consuming application of multiple layers of lacquer on an item’s surface led to the high price of lacquerware. Lacquer’s lightness, vibrant colors, and glossy surface made it as prestigious as ritual bronze vessels. Besides the coffins, the tomb also had an extensive collection of other lacquerwares—letting anyone know once again of Marquis Yi’s status.

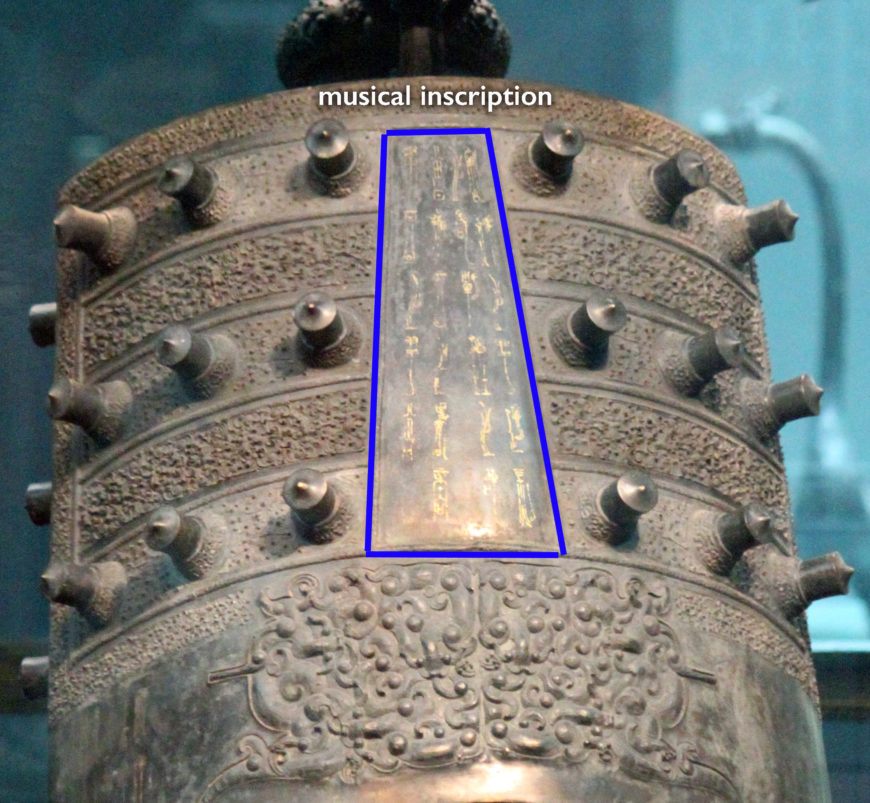

Chime Bell Set

The grand chime bell set is the largest item in the central chamber. In China, bronze musical bells trace their origin to the late second millennium B.C.E. clapperless nao-bells in the Yangtze River region in the south.

Nao-bells are a bronze bell tradition indigenous to the middle to lower Yangtze River region. Usually geometric in surface decoration and found in the hilltop or river bank, nao-bells are considerably more voluminous than their northern counterparts. The larger ones can be over 1-meter tall and weigh over 100 kg.

Western Zhou elites began to institutionalize chime bells in the 9th century B.C.E. Bells began to be organized to cover an octave, and musical theory gradually developed. This systematic change added an acoustic dimension to the visual and gustatory experiences in the ritual performance of ancestral offerings.

Food offerings for their deceased ancestors was a serious matter to the elites in Bronze Age China. The living sustained the deceased and the deceased, in return, blessed the living.

Marquis Yi’s bell set is the most extensive and best preserved known-to-date. Divided into eight groups, 65 bells occupy three tiers on L-shaped shelves. The wooden shelves, adorned by elaborate lacquer decoration and bronze components, are supported by six bronze statues of armed warriors. Unlike in Egypt and Mesopotamia in the third and second millennium B.C.E. where the appearance of the rulers was a major artistic theme, patrons and artists in early China almost purposefully eschewed direct human representations.

The bronze warriors in Marquis Yi’s bell set are a rare case of the representation of the human form in early Chinese art, indicative of the late first millennium trend toward increasing secularization. Scholars have proposed that the reason for this was that writing was ritually and politically more powerful than images in early China. We always see the name of the owner and that of the honored person cast on precious bronze vessels, but we almost never see the face of the patron in bronze art.

The bells range considerably in weight and height. Interlaced serpents in a dense pattern and granular texture rise up in low relief from the bell surface. Musical inscriptions in gold script are on the center, bottom, and side of the bells. A total of 3,755 characters explain in detail the pitches and scales that the chime bells are designed to play. Each bell is tuned to produce two clear pitches by striking the center and side. The entire set is capable of playing a five-note scale across five octaves. Tuning bronze bells is a highly technical, challenging task. Experienced Zeng state founders skillfully cast the bells with approximately correct pitches.

Our knowledge about the operation of a foundry at this time is limited. Bronze casting was likely a highly exclusive practice monopolized by the state, which also controlled labor, expertise, and raw materials.

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Listen to what the bells would have sounded like with modern-day reconstructions (video by Behring Global Educational Foundation)

A grand chime bell set would have been the center of court musical performances. Additional musical instruments, such as a 32-piece stone chime set, wooden zithers, drums, flutes, panpipes, and mouth organs, completed the ensemble. The bell set alone required a crew of five players. More than 20 musicians were needed to perform in the orchestra. The enormous labor and material investment in the court banquet certainly impressed most guests of Marquis Yi. What is more profound is the exceptional sophistication and grandeur of the musical system. Marquis Yi conveyed a strong message: Not only was he the head of an affluent state, he was also a highly cultured gentleman.

Ritual Bronze Vessels

Meticulously lined up in the southern end of the tomb’s central chamber are many bronze vessels, which are breathtaking for their sheer scale, volume, and technical virtuosity. Ritual bronze vessels like these were used in ancestral offering ceremonies in Bronze Age China. The correct performance would please the ancestors, and strengthen elite status and power in return. Food offerings were the primary form of ancestral offerings in Bronze Age China. Often human sacrifice, especially that of war captives, was a key component in the offering ceremony. The the vessels for offerings? in the tomb of the Marquis Yi are considered one of the most impressive examples.

Beginning in the middle to late Western Zhou period (c. 9th century B.C.E.), a loose ranking system emerged to regulate the ritual bronze use in accordance with someone’s prescribed elite status. The more bronze vessels you had, the higher your status. The king of the Zhou court (at the top of the social hierarchy) supposedly used 9 ding-cauldrons and 8 gui-basins, and his subordinate lords and princes were entitled to fewer vessels. The ding food-cauldron (which typically containing sacrificed animals) and the gui grain-basin were the centerpieces of the ritual paraphernalia for ancestral offering in Bronze Age China.

This regulative system began to relax in the late first millennium B.C.E., as we see with the marquis’s tomb. In it we find 9 ding-cauldrons and 8 gui-basins in the central chamber. They reveal the aspiration of Marquis Yi for a status beyond his reach as the ruler of a small southern state. Echoing the ritual relaxation at this time was the simplification and secularization of the bronze inscriptions. Most of Marquis Yi’s bronzes bear the simple inscription “Marquis Yi of Zeng makes, holds, and uses forever.” This inscription signals the broader shift from commemorative writing of the previous Western Zhou period to the straightforward indication of ownership in the Warring States period.

Marquis Yi’s bronzes represent the finest technical achievements in ancient bronze casting. Traditional piece-mold casting first emerged in the middle Yellow River valley in the early second millennium B.C.E. This technique was still practiced in the Zeng state foundry and accounts for most of Marquis Yi’s bronzes. The most spectacular of this long established casting method is the bronze drum base. A swarm of burly serpents vigorously swirl up from the circular base and appear to be boldly exhibiting their brawny physiques in response to music. Each serpent was individually cast and then joined together.

While the lost-wax casting prevailed in the Mediterranean world, the piece-mold casting was the primary casting method uniquely used in China. This technology draws on the rich tradition of pottery making in the Neolithic societies and employs an inner clay core and outer clay molds to cast bronze vessels. Decoration is either drawn directly on the outer molds or transferred to the molds from the original model.

Another technical masterpiece of piece-mold casting is a pair of wine storage jars, which are the most voluminous bronze vessels in the tomb. Their immense volume prevented the founders from completing the casting in one attempt. A wide band that runs through the middle of the vessel body indicates that the upper and lower half were cast separately and joined together afterward.

Outside the piece-mold casting, the Zeng state casters also mastered other production methods. Archaeologists usually credit the zun–pan basin and vase set to lost-wax casting. The rim, which appears to be thick and full, consists of intensive miniaturized serpents that curl up and interlace with each other. These intricate designs, especially the deep undercuts and three-dimensional layerings, are nearly technically impossible in piece-mold casting. In addition, the Zeng casters employed copper and lead soldering to connect accessories such as handles, knobs, and legs to the main body of bronze vessels.

Inlay also played a prominent role in decorating Marquis Yi’s bronzes. There are ritual bronze sacrificial food vessels inlaid with red copper or even turquoise ornaments. In both cases, the Zeng founders first cast the bronze vessel with pre-arranged negative grooves. They then cast the copper and inserted the turquoise in the intaglio lines before finally polishing up the surface of the vessel.

Regional politics

Beyond revealing to us the wealth and ambition of the marquis, certain items in the tomb also tell us about regional politics and trans-regional, Eurasian connections. One bell from the bell chime set shows us how one local ruler of a small state was well-connected to more powerful rulers and larger states than Zeng.

In the center of the chime bell set is a sizable bronze bo-bell with a straight rim that looks different from the other yong-bells (with concave rims) surrounding it. The vertical hanging pose of this central bo-bell also stands out from the uniform tilted suspension seen across the racks holding all the bells. An inscription on the bo-bell indicates that it was a present from Xiong Zhang, the King Hui of the Chu state.

While the lost-wax casting prevailed in the Mediterranean world, the piece-mold casting was the primary casting method uniquely used in China. This technology draws on the rich tradition of pottery making in the Neolithic societies and employs an inner clay core and outer clay molds to cast bronze vessels. Decoration is either drawn directly on the outer molds or transferred to the molds from the original model.

What did this gift mean for Marquis Yi?

The bo-bell indicates the importance of political strategizing during this time—by gifting it to the Marquis Yi of Zeng the nearby Chu king implies that the Zeng state was under the Chu protection (or even that Zeng was a client state to the Chu). The incorporation of the bell into the larger chime bell set suggests that Marquis Yi accepted the political patronage from the Chu state. While the gift suggests Marquis Yi had to compromise some of his power, his burial arrangement also appropriated kingly ritual prestige items like the 9 ding and 8 gui, which were usually reserved for the Zhou ruler. Borrowing from the kingly ritual bronze setting was more of a ceremonial rather than a political statement. Though he probably had less respect for the authority of the central Zhou court, Marquis Yi was not intending to usurp the throne and seize actual power.

Eurasian Connections

Certain objects in the tomb speak to the increased cultural exchange across the Eurasian continent at this time. 172 glass compound eye beads discovered in the inner coffin were the result of a wave of transcontinental communication. These glass beads, known as the “dragonfly eyes,” were a short-lived fad in Warring States China. Commonly featuring blue concentric circles in bright green or yellow background, compound eye beads find their earlier counterparts in Egypt, Iran, and the eastern Mediterranean. Raman spectroscopy examination shows that the colorants of Marquis Yi’s beads are primarily calcium- and sodium-based, which share similar chemical compositions with beads from West Asia. They were likely directly imported from the west. Soon Chinese craftsmen adopted the form of the exotic glass beads and achieved a comparable look with the locally sourced lead and barium.

This technique utilizes the properties of Raman Scattering, which emits a laser beam to detect the vibration of molecules and, subsequently, analyze the chemical composition of the sample.

Recent archaeological excavations have unveiled matching glass beads in Scythian burials in Central Asia, implying that the nomads living in the Steppe played a vital role in the long-distance dissemination of the compound eye beads.

From massive burial chambers and gigantic double coffins to grand bronze vessels and chime bells, the tomb of Marquis Yi comprehensively reveals to us the splendid and sophisticated elite life in the Warring States period. All these rich furnishings expressively display the power and wealth of Marquis Yi and enabled his prestige and privilege to continue in the afterlife.

Additional resources

“China, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Resound: Ancient Bells of China,” National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian

Bells of Ancient China, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian

“Introduction to Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng,” Hubei Provincial Museum

The Marquis Yi of Zeng, Bronze Objects, on Google Arts and Culture

The Marquis Yi of Zeng, Gold and Jade Objects, on Google Arts and Culture

Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. -220 C.E.)

Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui)

Maybe you can bring it with you…if you are rich enough. The elite men and women of the Han dynasty (China’s second imperial dynasty, 206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) enjoyed an opulent lifestyle that could stretch into the afterlife. Today, the well-furnished tombs of the elite give us a glimpse of the luxurious goods they treasured and enjoyed. For instance, a wealthy official could afford beautiful silk robes in contrast to the homespun or paper garments of a laborer or peasant. Their tombs also inform us about their cosmological beliefs.

Marquis of Dai, Lady Dai, and a son

Three elite tombs, discovered in 1972, at Mawangdui, Hunan Province (eastern China) rank amongst the greatest archeological discoveries in China during the twentieth century. They are the tombs of a high-ranking Han official civil servant, the Marquis of Dai, Lady Dai (his wife), and their son. The Marquis died in 186 B.C.E., and his wife and son both died by 163 B.C.E. The Marquis’ tomb was not in good condition when it was discovered. However, the objects in the son’s and wife’s tombs were of extraordinary quality and very well preserved. From these objects, we can see that Lady Dai and her son were to spend the afterlife in sumptuous comfort.

In Lady Dai’s tomb, archaeologists found a painted silk banner over six feet long in excellent condition. The T-shaped banner was on top of the innermost of four nesting coffins. Although scholars still debate the function of these banners, we know they had some connection with the afterlife. They may be “name banners” used to identify the dead during the mourning ceremonies, or they may have been burial shrouds intended to aid the soul in its passage to the afterlife. Lady Dai’s banner is important for two primary reasons. It is an early example of pictorial (representing naturalistic scenes not just abstract shapes) art in China. Secondly, the banner features the earliest known portrait in Chinese painting.

We can divide Lady Dai’s banner into four horizontal registers (see diagram). In the lower central register, we see Lady Dai in an embroidered silk robe leaning on a staff. This remarkable portrait of Lady Dai is the earliest example of a painted portrait of a specific individual in China. She stands on a platform along with her servants–two in front and three behind.

Long, sinuous dragons frame the scene on either side, and their white and pink bodies loop through a bi (a disc with a hole thought to represent the sky) underneath Lady Dai. We understand that this is not a portrait of Lady Dai in her former life, but an image of her in the afterlife enjoying the immortal comforts of her tomb as she ascends toward the heavens.

In the register below the scene of Lady Dai, we see sacrificial funerary rituals taking place in a mourning hall. Tripod containers and vase-shaped vessels for offering food and wine stand in the foreground. In the middle ground, seated mourners line up in two rows. Look for the mound in the center, between the two rows of mourners. If you look closely, you can see the patterns on the silk that match the robe Lady Dai wears in the scene above. Her corpse is wrapped in her finest robe! More vessels appear on a shelf in the background.

In the mourning scene, we can also appreciate the importance of Lady Dai’s banner for understanding how artists began to represent depth and space in early Chinese painting. They made efforts to indicate depth through the use of the overlapping bodies of the mourners. They also made objects in the foreground larger, and objects in the background smaller, to create the illusion of space in the mourning hall.

The afterlife in Han dynasty China

Lady Dai’s banner gives us some insight into cosmological beliefs and funeral practices of Han dynasty China. Above and below the scenes of Lady Dai and the mourning hall, we see images of heaven and the underworld. Toward the top, near the cross of the “T,” two men face each other and guard the gate to the heavenly realm. Directly above the two men, at the very top of the banner, we see a deity with a human head and a dragon body.

On the left, a toad standing on a crescent moon flanks the dragon/human deity. On the right, we see what may be a three-legged crow within a pink sun. The moon and the sun are emblematic of a supernatural realm above the human world. Dragons and other immortal beings populate the sky. In the lower register, beneath the mourning hall, we see the underworld populated by two giant black fish, a red snake, a pair of blue goats, and an unidentified earthly deity. The deity appears to hold up the floor of the mourning hall, while the two fish cross to form a circle beneath him. The beings in the underworld symbolize water and earth, and they indicate an underground domain below the human world.

Four compartments surrounded Lady Dai’s central tomb, and they offer some sense of the life she was expected to lead in the afterlife. The top compartment represented a room where Lady Dai was supposed to sit while having her meal. In this compartment, researchers found cushions, an armrest and her walking stick. The compartment also contained a meal laid out for her to eat in the afterlife. Lady Dai was 50 years old when she died, but her lavish tomb—marked by her funeral banner —ensured that she would enjoy the comforts of her earthly life for eternity.

This essay was written with the assistance of Dr. Wu Hung.

Additional Resources:

This object at the Han Provincial Museum

Northern Wei dynasty (386-534 C.E.)

Longmen caves, Luoyang

Imperial patronage

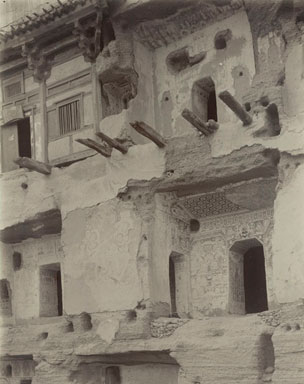

Worship and power struggles, enlightenment and suicide—the 2300 caves and niches filled with Buddhist art at Longmen in China has witnessed it all. The steep limestone cliffs extend for almost a mile and contain approximately 110,000 Buddhist stone statues, 60 stupas (hemispherical structures containing Buddhist relics) and 2,800 inscriptions carved on steles (vertical stone markers).

Buddhism, born in India, was transmitted to China intermittently and haphazardly. Starting as early as the 1st century C.E., Buddhism brought to China new images, texts, ideas about life and death, and new opportunities to assert authority. The Longmen cave-temple complex, located on both sides of the Yi River (south of the ancient capital of Luoyang), is an excellent site for understanding how rulers wielded this foreign religion to affirm assimilation and superiority.

Northern Wei Dynasty

Most of the carvings at the Longmen site date between the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 8th century—the periods of the Northern Wei (386–534 C.E.) through early Tang dynasties (618–907 C.E.). The Northern Wei was the most enduring and powerful of the northern Chinese dynasties that ruled before the reunification of China under the Sui and Tang dynasties.

The Wei dynasty was founded by Tuoba tribesmen (nomads from the frontiers of northern China) who were considered to be barbaric foreigners by the Han Chinese. Northern Wei Emperor Xiao Wen decided to move the capital south to Luoyang in 494 C.E., a region considered the cradle of Chinese civilization. Many of the Tuoba elite opposed the move and disapproved of Xiao Wen’s eager adoption of Chinese culture. Even his own son disapproved and was forced to end his own life. At first, Emperor Xiao Wen and rich citizens focused on building the city’s administrative and court quarters—only later did they shift their energies and wealth into the construction of monasteries and temples. With all the efforts expended on the city, the court barely managed to complete one cave temple at Longmen—the Central Binyang Cave.

Central Binyang Cave

The Central Binyang Cave was one of three caves started in 508 C.E. It was commissioned by Emperor Xuan Wu in memory of his father. The other two caves, known as Northern and Southern Binyang, were never completed.

Imagine being surrounded by a myriad of carvings painted in brilliant blue, red, ochre and gold (most of the paint is now gone). Across from the entry is the most significant devotional grouping—a pentad (five figures—see image below).

The central Buddha, seated on a lion throne, is generally identified as Shakyamuni (the historical Buddha), although some scholars identify him as Maitreya (the Buddha of the future) based on the “giving” mudra—a hand gesture associated with Maitreya. He is assisted by two bodhisattvas and two disciples—Ananda and Kasyapa (bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have put off entering paradise in order to help others attain enlightenment).

The Buddha’s monastic robe is rendered to appear as though tucked under him (image above). Ripples of folds cascade over the front of his throne. These linear and abstract motifs are typical of the mature Northern Wei style (as also seen in this gilt bronze statue of Buddhas Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna, from 518 C.E.). The flattened, elongated bodies of the Longmen bodhisattvas (image left) are hidden under elaborately pleated and flaring skirts. The bodhisattvas wear draping scarves, jewelry and crowns with floral designs. Their gentle, smiling faces are rectangular and elongated.

Low relief carving covers the lateral walls, ceiling, and floor. Finely chiseled haloes back the images. The halo of the main Buddha extends up to merge with a lotus carving in the middle of the ceiling, where celestial deities appear to flutter down from the heavens with their scarves trailing. In contrast to the Northern Wei style seen on the pentad, the sinuous and dynamic surface decoration displays Chinese style. The Northern Wei craftsmen were able to marry two different aesthetics in one cave temple.

Two relief carvings of imperial processions (below) once flanked the doorway of the cave entrance. The emperor’s procession is at the Metropolitan Museum, while the empress’s procession is at the Nelson-Atkins Museum. These reliefs most likely commemorate historic events. According to records, the Empress Dowager visited the caves in 517 C.E., while the Emperor was present for consecration of the Central Binyang in 523 C.E.

These reliefs are the most tangible evidence that the Northern Wei craftsmen masterfully adopted the Chinese aesthetic. The style of the reliefs may be inspired by secular painting, since the figures all appear very gracious and solemn. They are clad in Chinese court robes and look genuinely Chinese—mission accomplished for the Northern Wei!

Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.) is considered the age of “international Buddhism.” Many Chinese, Indian, Central Asian and East Asian monks traveled throughout Asia. The centers of Buddhism in China were invigorated by these travels, and important developments in Buddhist thought and practice originated in China at this time.

Fengxian Temple

This imposing group of nine monumental images carved into the hard, gray limestone of Fengxian Temple at Longmen is a spectacular display of innovative style and iconography. Sponsored by the Emperor Gaozong and his wife, the future Empress Wu, the high relief sculptures are widely spaced in a semi-circle.

The central Vairocana Buddha (more than 55 feet high including its pedestal) is flanked on either side by a bodhisattva, a heavenly king, and a thunderbolt holder (vajrapani). Vairocana represents the primordial Buddha who generates and presides over all the Buddhas of the infinite universes that form Buddhist cosmology. This idea—of the power of one supreme deity over all the others—resonated in the vast Tang Empire which was dominated by the Emperor at its summit and supported by his subordinate officials. These monumental sculptures intentionally mirrored the political situation. The dignity and imposing presence of Buddha and the sumptuous appearance of his attendant bodhisattvas is significant in this context.

The Buddha, monks and bodhisattvas (above) display new softer and rounder modeling and serene facial expressions. In contrast, the heavenly guardians and the vajrapani are more engaging and animated. Notice the realistic musculature of the heavenly guardians and the forceful poses of the vajrapani (below).

Kanjing Temple

Tang dynasty realism—whether fleshy or wizened, dignified or light-hearted—is displayed in the Kanjing cave Temple at Longmen. Here we see accurate portrayals of individuals. This temple was created from about 690-704 C.E. under the patronage of Empress Wu.

In the images of arhats (worthy monks who have advanced very far in their quest of Enlightenment), who line the walls, the carver sought to create intense realism. Although they are still mortal, arhats are capable of extraordinary deeds both physical and spiritual (they can move at free will through space, can understand the thoughts in people’s minds, and hear the voices of far away speakers). Twenty-nine monks form a procession around the cave perimeter, linking the subject matter to the rising interest in Chan Buddhism (the Meditation School) fostered at court by the empress herself. These portraits record the lineage of the great patriarchs who transmitted the Buddhist doctrine.

Sovereignty and iconography

Foreign rulers of the Northern Wei, yearning for assimilation and control, made use of Buddhist images for authority and power. Tang dynasty leaders thrived during China’s golden age, asserting their sovereignty with the assistance of Buddhist iconography. Today you can visit the stunning limestone remains in Luoyang, New York City, and Kansas City.

The author would like to thank her teacher, Professor Angela Howard.

Northern Qi dynasty (550-577)

Bodhisattva, probably Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin)

by DR. JENNIFER N. MCINTIRE and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Bodhisattva, probably Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin), Northern Qi dynasty, c. 550-60, Shanxi Province, China, sandstone with pigments, 13-3/4 feet / 419.1 cm high (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The art of the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty was one of the most powerful in Chinese history. In this period, China becomes the the most prominent civilization in East Asia—with links east to Korea and Japan and west, along the Silk Route.

618 - 907

Chinese Buddhist cave shrines

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): This video explores ancient Buddhist cave shrines in China, including why the sites were created and the major sponsors and patrons. Video from the Asian Art Museum.

Mogao caves at Dunhuang

A trove of Buddhist art

The ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas’ (Qianfodong), also known as Mogao, are a magnificent treasure trove of Buddhist art. They are located in the desert, about 15 miles south-east of the town of Dunhuang in north western China. By the late fourth century, the area had become a busy desert crossroads on the caravan routes of the Silk Road linking China and the West. Traders, pilgrims and other travellers stopped at the oasis town to secure provisions, pray for the journey ahead or give thanks for their survival. Records state that in 366 monks carved the first caves into the cliff stretching about 1 mile along the Daquan River.

An archive rediscovered

At some point in the early eleventh century, an incredible archive—with up to 50,000 documents, hundreds of paintings, together with textiles and other artefacts—had been sealed up in a chamber adjacent to one of the caves (Cave 17). Its entrance was concealed behind a wall painting and the trove remained hidden from sight for centuries. In 1900, it was discovered by Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist monk who had appointed himself abbot and guardian of the cave-temples. The first Western expedition to reach Dunhuang arrived in 1879. More than twenty years later Hungarian-born Marc Aurel Stein, a British archaeologist and explorer, learned of the importance of the caves.

Stein reached Dunhuang in 1907. He had heard rumours of the walled-in cave and its contents. The abbot sold Stein seven thousand complete manuscripts and six thousand fragments, as well as several cases loaded with paintings, embroideries and other artifacts. French explorer Paul Pelliot followed close on Stein’s heels. Pelliot remarked in a letter, “During the first ten days I attacked nearly a thousand scrolls a day…”

Other expeditions followed and returned with many manuscripts and paintings. The result is that the Dunhuang manuscripts and scroll paintings are now scattered over the globe. The bulk of the material can be found in Beijing, London, Delhi, Paris, and Saint Petersburg. Studies based on the textual material found at Dunhuang have provided a better understanding of the extraordinary cross-fertilization of cultures and religions that occurred from the fourth through the fourteenth centuries.

A thousand years of art

There are about 492 extant cave-temples ranging in date from the fifth to the thirteenth centuries. During the thousand years of artistic activity at Dunhuang, the style of the wall paintings and sculptures changed. The early caves show greater Indian and Western influence, while during the Tang dynasty (618-906 C.E.) the influence of the Chinese painting styles of the imperial court is apparent. During the tenth century, Dunhuang became more isolated and the organization of a local painting academy led to mass production of paintings with a unique style.

The cave-temples are all man-made, and the decoration of each appears to have been conceived and executed as a conceptual whole. The wall-paintings were done in dry fresco. The walls were prepared with a mixture of mud, straw, and reeds that were covered with a lime paste. The sculptures are constructed with a wooden armature, straw, reeds, and plaster. The colors in the paintings and on the sculptures were done with mineral pigments as well as gold and silver leaf. All the Dunhuang caves face east.

Changes in belief

The art also reflects the changes in religious belief and ritual at the pilgrim site. In the early caves, jataka tales (previous lives of the Historical Buddha) were commonly depicted. During the Tang dynasty, Pure Land Buddhism became very popular. This promoted the Buddha Amitabha, who helped the believer achieve rebirth in his Western Paradise, where even sinners are permitted, sitting within closed lotus buds listening to the heavenly sounds and the sermon of the Buddha, thus purifying them. Various Paradise paintings decorate the walls of the cave-temples of this period, each representing the realm of a different Buddha. Their Paradises are depicted as sumptuous Chinese palace settings.

Images of the caves

During WWII the famous, contemporary Chinese painter Zhang Daqian spent time at Dunhuang with his students. They copied the cave paintings. Photojournalist James Lo—a friend of Zhang Daqian—joined him at Dunhuang and systematically photographed the caves. Traveling partly on horseback, they arrived at Dunhuang in 1943 and began a photographic campaign that continued for eighteen months. The Lo Archive (a set is now housed at Princeton University) consists of about 2,500 black-and-white historic photographs. Since no electricity was available, James Lo devised a system of mirrors and cloth screens that bounced light along the corridors of the caves to illuminate the paintings and sculptures.

Today the Mogao cave-temples of Dunhuang are a World Heritage Site. Under a collaborative agreement with China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH), the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) has been working with the Dunhuang Academy since 1989 on conservation. Tourists can visit selected cave-temples with a guide.

Backstory

The Mogao caves at Dunhuang were reclaimed from the encroaching Gobi desert beginning in the early twentieth century, but their conservation is an ongoing challenge. In addition to natural threats like sandstorms and rainwater, the caves’ delicate murals face damage caused mainly by tourists (hundreds of thousands per year, up to 6,000 per day), whose presence adds dangerous levels of carbon dioxide and humidity to the air. Fortunately, much is being done to preserve the artworks at Dunhuang—and new technologies are also making it possible for the caves to be meticulously documented and shared around the world.

The Mogao caves were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, and are overseen by international watchdog groups as well as a state-run institution called the Dunhuang Research Academy. Since 1989, they have been working with China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage and the Getty Conservation Institute on structural reinforcement, careful restoration and stabilization of the murals, and digital documentation. The Mogao caves were also a test site for the development of the China Principles, a set of international standards for preserving cultural heritage—not only in terms of physical assets, but also with respect to local traditions, environment, and history.

Images of the caves were first produced during World War II, when the famous contemporary Chinese painter Zhang Daqian spent time copying the cave paintings with his students. Photojournalist James Lo joined the effort by systematically photographing the caves using an ingenious system of mirrors to bounce natural light into the dark spaces. The Lo Archive (a set is now housed at Princeton University) consists of about 2,500 black-and-white photographs.

In recent years, teams have been working to create physical replicas of the caves that can be displayed at museums and other sites around the world. Virtual reality technology has also been used to create immersive media environments that replicate the experience of being in the caves, and preserve important data about the spaces’ measurements and other physical properties. These types of reproductions can also help reduce the effects of human presence in the caves by making digital reconstructions available at Dunhuang itself: visitors can spend time looking closely at these “digital caves,” allowing for stricter time limits and lower visitor numbers in the caves themselves. In addition, these digital versions can be shared easily around the world, along with a growing archive of high-quality photographs. The manuscripts and other objects from Cave 17, discussed above, have also been digitized and are available online.

New technologies are also making it possible to preserve and share data about other important Buddhist sites in China. At the Yungang Grottoes in northeastern China, where the sculpture is threatened not only by tourism but also by China’s high levels of industrial air pollution and acid rain, 3-D scanning is being used to model the monumental sculptures and create highly accurate reproductions that can be shared and shown around the globe.

The Mogao caves and Yungang Grottoes are outstanding human achievements that are now threatened by other types of human endeavors: climate change, tourism, and pollution. The continued development of new technologies and approaches for preserving and documenting these invaluable sites is essential to their survival.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources

International Dunhuang Project

The Caves at Dunhuang – New York Times Slideshow and related article by Holland Carter

Dunhuang Manuscripts on Wikipedia UNESCO World Heritage Site

Application of the China Principles at the Mogao Grottoes from the Getty Research Institute

Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road at the Getty Research Institute

The paintings and manuscripts from cave 17 at Mogao (1 of 2)

Buddhism in China

Buddhism probably arrived in China during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.), and became a central feature of Chinese culture during the period of division that followed. Buddhist teaching ascribed great merit to the reproduction of images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, in which the artisans had to follow strict rules of iconography.

A twelfth-century catalogue of the Chinese imperial painting collection lists Daoist and Buddhist works from the time of Gu Kaizhi (c. 344-406 C.E.) onwards. However, no paintings by major artists of this period have survived, because foreign religions were proscribed between 842 and 845, and many Buddhist monuments and works of art were destroyed.

The Valley of the Thousand Buddhas

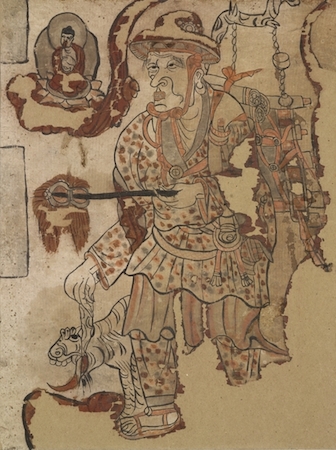

What has survived from the Tang period (618-906) is an important collection of Buddhist paintings on silk and paper, found in Cave 17, in the Valley of the Thousand Buddhas at the Chinese end of the Silk Road. Since Dunhuang was under Tibetan occupation at this time, its cave shrines and paintings escaped destruction.

The “Caves of the Thousand Buddhas,” or Qianfodong, are situated at Mogao, about 25 kilometres south-east of the oasis town of Dunhuang in Gansu province, western China, in the middle of the desert. By the late fourth century, the area had become a busy desert crossroads on the caravan routes of the Silk Road linking China and the West. Traders, pilgrims and other travelers stopped at the oasis town to stock up with provisions, pray for the journey ahead or give thanks for their survival. At about this time wandering monks carved the first caves into the long cliff stretching almost 2 kilometers in length along the Daquan River.

Over the next millennium more than 1000 caves of varying sizes were dug. Around five hundred of these were decorated as cave temples, carved from the gravel conglomerate of the escarpment. This material was not suitable for sculpture, as at other famous Buddhist cave temples at Yungang and Longmen. The Caves of the Thousand Buddhas gained their name from the legend of a monk who dreamt he saw a cloud with a thousand Buddhas floating over the valley.

Sealed for a thousand years, then rediscovered

When the Silk Road was abandoned under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), oasis towns lost their importance and many were deserted. Although the Mogao caves were not completely abandoned, by the nineteenth century they were largely forgotten, with only a few monks staying at the site. Unknown to them, at some point in the early eleventh century, an incredible archive—with up to 50,000 documents, hundreds of paintings, together with textiles and other artifacts—was sealed up in one of the caves (Cave 17). Its entrance concealed behind a wall painting, the cave remained hidden from sight for centuries, until 1900, when it was discovered by Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist monk who had appointed himself abbot and guardian of the caves.

The first Western expedition to reach Dunhuang, led by a Hungarian count, arrived in 1879. More than twenty years later one of its members, Lajos Lóczy, drew the attention of the Hungarian-born Marc Aurel Stein, by then a well-known British archaeologist and explorer, to the importance of the caves. Stein reached Dunhuang and Mogao in 1907 during his second expedition to Central Asia. By this time, he had heard rumors of the walled-in cave and its contents.

After delicate negotiations with Wang Yuanlu, Stein negotiated access to the cave. “Heaped up in layers,” Stein wrote, “but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest’s little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet…. Not in the driest soil could relics of a ruined site have so completely escaped injury as they had here in a carefully selected rock chamber, where, hidden behind a brick wall, …. these masses of manuscripts had lain undisturbed for centuries.” (M. Aurel Stein,Ruins of Desert Cathay (1912; reprint, New York, Dover, 1987).

The abbot eventually sold Stein seven thousand complete manuscripts and six thousand fragments, as well as several cases loaded with paintings, embroideries and other artifacts; the money was used to fund restoration work at the caves.The manuscripts are now in the British Library and the paintings have been divided between the National Museum in New Delhi and the British Museum, where over three hundred paintings on silk, hemp and paper are kept.

This painting is inscribed with the characters yinlu pu or “Bodhisattva leading the Way.” It is one of several examples from Mogao of a bodhisattva leading the beautifully clad donor figure to the Pure Land, or Paradise, indicated by a Chinese building floating on clouds in the top left corner. The two figures are also supported by a cloud indicating that they are flying.

The bodhisattva, shown much larger than the donor, is holding a censer and a banner in his hand. The banner is one of many of the same type found at Mogao, with a triangular headpiece and streamers. The woman appears to be very wealthy, with gold hairpins in her hair. Actual examples of these were found in Chinese tombs. Her fashionably plump figure suggests that the painting was executed in the ninth or tenth century.

Suggested readings:

H. Wang (ed.), Sir Aurel Stein. Proceedings of the British Museum Study Day 2002 (London, British Museum Occasional Paper 142, 2004).

H. Wang, Money on the Silk Road. The Evidence from Eastern Central Asiato c. AD 800 (London, British Museum Press, 2004).

S. Whitfield, Aurel Stein on the Silk Road (London, British Museum Press, 2004).

J. Falconer, A. Kelecsenyi, A. Karteszi and L. Russell-Smith (E. Apor and H. Wang eds.), Catalogue of the Collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (published jointly by the British Museum and the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest [LHAS Oriental Series 11], 2002).

H. Wang (ed.), Handbook to the Stein Collections in the UK (London, British Museum Occasional Paper 129, 1999).

© Trustees of the British Museum

The paintings and manuscripts from cave 17 at Mogao (2 of 2)

Change over a thousand years

During the thousand years of artistic activity at Mogao, the style of the wall paintings and sculptures changed, in part a reflection of the influences that reached it along the Silk Road. The early caves show greater Indian and Western influence, while during the Tang dynasty (618-906) the influence of the latest Chinese painting styles of the imperial court is evident. During the tenth century, Dunhuang became more isolated and the organization of a local painting academy led to mass production of paintings with a unique style.

The art also reflects the changes in religious belief and ritual at the pilgrim site. In the early caves, jataka stories (about Buddha’s previous incarnations) were commonly depicted. During the Tang dynasty, Pure Land Buddhism became very popular. This promoted the Buddha Amitabha, who helped the believer achieve rebirth in his Western Paradise, where even sinners are permitted, sitting within closed lotus buds listening to the heavenly sounds and the sermon of the Buddha, thereby purifying themselves.