7.13: 17th century- Baroque (II)

- Page ID

- 73312

Dutch Republic

A prosperous middle class eager to express its status and its new sense of national pride, replaced the church and monarchy as the primary patrons of art.

1600 - 1700

Frans Hals

Frans Hals, Singing Boy with Flute

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Frans Hals, Singing Boy with Flute, c. 1623, oil on canvas, 68.8 x 55.2 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Frans Hals, Malle Babbe

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Frans Hals, Malle Babbe, c. 1633, oil on canvas, 78.50 x 66.20 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Frans Hals, The Women Regents

by OLIVIA NICOLE MILLER

“[He] excels almost everyone with the superb and uncommon manner of painting which is uniquely his …. [His portraits] are colored in such a way that they seem to live and breathe.”—Theodor Schrevelius (1572-1649)

Haarlem was a prominent city in the seventeenth-century Netherlands and a leading center for the Golden Age of Dutch art. Still life, landscape, and genre painting were wildly popular, but there was also a surge in portrait commissions due to the newfound wealth of the many merchants who flocked to this area. As one of the foremost painters of this period, Frans Hals received many portrait commissions—especially from the Haarlem elite who sought to preserve their likeness and demonstrate their status. Hals’s painterly approach to art set him apart from his contemporaries; there is a looseness in his brushwork and liveliness in his sitters that is unique.

For the open market (in other words, not commissioned works), Hals created portraits of the common members of society including children, drunkards, and musicians—most are depicted smiling or laughing (far removed from the more reserved representations of the elite).

Depicting these marginal figures allowed Hals the freedom to experiment with facial expressions while still maintaining each figure’s individuality (above and below left). Hals received many commissions from wealthy individuals, but also made a name for himself with his group portraits. Some of these prestigious commissions were for guilds (associations of craftsmen or merchants) or civic guards, while others, such as The Women Regents (top of page) were for charitable groups.

Group portraits such as these were typically displayed in a public space where the sitters’ status and good deeds could be recognized. Founded in 1609, the Old Men’s Almshouse (Oude Mannenhuis) was governed by a board of regents and provided shelter and care for elderly single men. This portrait, along with its companion painting depicting the male regents (below), was likely made in 1664, when Hals was 81 or 82 years old. In The Women Regents five women are clustered around a table in the immediate foreground. The painting is somber—dominated by blacks and grays that are punctuated by the white collars of the women’s clothes. Depicted in traditional Calvinist clothing, the women are not only representing their caretaking profession, but also the dominant religion of the Dutch Republic.

The women are quiet and austere. Perhaps they are weary from their responsibility in caring for the elderly poor, or perhaps they are simply serious about their task of governing the almshouse. Regardless, there is a dignity in the figures and a clear intention to individualize them, both through their likenesses and different poses.

The background is simple; a landscape painting hangs on the wall behind the women and a large swath of drapery sweeps across the upper left corner. Although it is a stark contrast from Hals’s jovial militia banquet group portraits (below), there is still a sense of a captured moment in time. The women are posed and arranged so that the viewer has a full view of each of them. A few of them are in mid-pose—one even appears to have just entered the scene from the right. Only three stare out at the viewer. Textured brushwork combined with the repetitive triangular shapes of the women’s bodies and their collars provide a sense of movement. While this painting is a stark contrast from his earlier jovial portraits of individuals, The Women Regents still embodies Hals’ penchant for expressive and textured brushwork. This technique is especially evident in the cuffs of the central standing figure where the brushstrokes simultaneously retain their painterly quality and give the illusion of texture. The cuffs are rendered with a series of quick lines encircling the woman’s wrists, yet from afar the paint strokes blend together, alluding to the qualities of a stiff, pleated fabric. Overall, the scene is still; however, through his virtuosity in brushwork, Hals has bestowed it with a sense of life, as if this painting represents these women in a specific moment in time.

There is scant information about Hals’s early life and upbringing. He was born in Antwerp, but moved to Haarlem as a child where he spent the entirety of this life. The first significant recorded moment of his artistic career is when he joined the painters’ guild of St. Luke in Haarlem in 1610, however there is little reliable information regarding his artistic training. Unfortunately he suffered financial obstacles throughout his life and was forced to sell many of his paintings and personal goods in order to repay debts and care for his many children. Although Hals died in relative poverty, his influence was significant. Judith Leyster employed Hal’s loose handling of paint and sense of the moment in her own portraits, and centuries later the Impressionists admired his brushwork.

Today visitors can see The Women Regents and many other Hals paintings at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem (above), which just so happens to be in the building of the former Old Men’s Almshouse.

Additional Resources:

Hals on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Christopher Atkins, The Signature Style of Frans Hals: Painting, Subjectivity, and the Market in Early Modernity (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011).

Calvinism and Religious Toleration in the Dutch Golden Age. Edited by R. Po-Chia Hsia and Henk F. K. van Nierop. (New York: Cambridge University Press. 2002).

Walter Liedtke, Frans Hals: Style and Substance (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011).

Rembrandt

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Rembrandt van Rijn, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632, oil on canvas, 169.5 x 216.5 cm, (Mauritshuis, Den Haag)

A prolific career

It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn within the history of Western art. Indeed, Rembrandt is considered one of the foremost artists of the Dutch Baroque period, and even if he had never picked up a paintbrush, he would have been famous both in his day and ours as a printmaker of particular brilliance and as a prolific teacher. In a career that lasted nearly forty years, Rembrandt completed approximately 400 paintings, more than 1,000 drawings, and nearly 300 engravings. Although he spent his entire life north of the alps, had he been Italian and lived a century or so earlier, he likely would have joined his Italian brethren—Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, as a member of the famed cartoon Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Patrons: A wealthy, Protestant, and expanding middle class

But as time and place would have it, Rembrandt was neither Italian nor a part of the Renaissance. Instead, Rembrandt was born in Leiden in 1606. This place and time—Holland during the height of the expansion of the wealthy mercantile class during the middle half of the seventeenth century—served Rembrandt well through his long career. The Catholic Church often commissioned Italian artists at this time to undertake large-scale projects to promote religious ideology in support of the Counter-Reformation. Without the Catholic Church in Holland to commission art, Rembrandt and his fellow Dutch artists were lavishly supported by a wealthy, Protestant, and expanding middle class. This group of patrons enthusiastically commissioned works of art with their increasing discretionary income.

New subjects (including group portraits)

Many different types of art became popular during the Dutch Baroque period. Genre paintings—small paintings of everyday life—were exceptionally popular with a middle-class clientele, as were still lifes, landscapes, and prints. The majority of these kinds of art were both affordable and small enough to be easily displayed within an average home. Larger and more compositionally complicated, group portraiture also became popular in Holland during the seventeenth century. This was a mode of painting that was often placed in a public space so that the image could promote a particular organization.

Relocating to Amsterdam

Although several of Rembrandt’s most well-known paintings are group portraits—The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp among others—his early education in Leiden, first at a Latin school and then later at the university, suggest that he was destined for a vocation other than art. However, by the time he was sixteen he decided he wanted to be a painter and a draughtsman. After finding quick success in Leiden during the 1620s, Rembrandt relocated to Amsterdam in 1631, a wise professional decision, as this was then one of the wealthiest and largest cities in Europe.

A group portrait for the Amsterdam Surgeon’s Guild

Just a year after his arrival, Rembrandt was offered the commission to complete a group portrait of the Amsterdam Surgeon’s Guild, an image that in time has come to be known rather simply as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp. It is remarkable that Rembrandt received this commission as a newcomer to Amsterdam when there were other native-born artists available. Thomas de Keyser (above) and Nicolaes Pickenoy (below), for example, were older and more experienced in the realm of group portraiture. Whereas another artist may have simply recreated a previous group image—inserting new heads in place of old ones—Rembrandt created something new, and in doing so, completed one of the most recognizable images in the history of painting.

Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Dr. Nicolaes Tulp was appointed praelector (like a professor or lecturer) of the Amsterdam Anatomy Guild in 1628. One of the responsibilities of this position was to deliver a yearly public lecture on some aspect of human anatomy. The lecture in 1632 occurred on 16 January, and this is the scene that Rembrandt depicts in paint in The Anatomy of Lesson of Dr. Tulp.

This is a more complicated composition than it at first appears. Understandably, the focal point of the image is Dr. Tulp, the doctor who is shown displaying the flexors of the cadaver’s left arm. Rembrandt notes the doctor’s significance by showing him as the only person who wears a hat. Seven colleagues surround Dr. Tulp, and they look in a variety of directions—some gaze at the cadaver, some stare at the lecturer, and some peek directly at the viewer. Each face displays a facial expression that is deeply personal and psychological. The cadaver—a recently executed thief named Adriaen Adriaenszoon—lies nearly parallel to the picture plane. Viewing the illuminated body from his head to his feet brings into focus a book—likely Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (Fabric of the Human Body, 1543)—propped up in the lower right corner. In all, Rembrandt shows nine distinct figures, but does so as if they are a unified group.

A comparison

Comparing The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp to a somewhat similar example, The Osteology Lesson of Dr. Sebastiaen Egbertszoon, shows just how different and novel Rembrandt’s composition was at the time. The Sebastiaen Erbertszoon painting is a series of six portraits that surround a single human skeleton; but neither the heads nor the bodies seem to interact with one another in a real or coherent way. In contrast, the figures in Rembrandt’s Tulp seem to truly be a group, one collection of nine rather than nine individuals.

If the composition is different from what Rembrandt might have seen in Amsterdam, the choice of subject is different than what would have been expected in the parts of Europe that were Catholic. The Catholic tenet of resurrection necessitated that dead bodies be interred in a state of wholeness, and this fact explains why Leonardo was forced to dissect human bodies in secret. In Protestant Holland but 113 years after Leonardo’s death, however, human dissections were not only common practice, they were often public spectacles, complete with food and wine, music and conversation.

Artistic license

If Rembrandt was able to create a truly group portrait—one of a single group rather than a collection of individuals—it is important to note that the artist took some understandable artistic license with some parts of the composition. As any anatomy and physiology student today can attest, a dissection of the human body almost always commences with an exploration of the chest and abdominal areas, parts of the human body most likely to decompose first, and only later does the procedure move onwards to the limbs. Moreover, it would have been unlikely that a doctor of Tulp’s importance would have actually dissected the body; instead, he would have lectured while the menial task of exposing the inner workings of the body would have been left to others. But in paint, a format without sound, Rembrandt put Tulp in charge not only in costume, but also in action.

As the prominent signature in the upper part of the painting indicates, Rembrandt was justifiably proud of this large painting.

Whereas he had previously signed his works with his monogram RHL (Rembrandt Harmenszoon of Leiden), The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp contains Rembrant. f[ecit] 1632. This painting and the Latin announcement that “Rembrandt made it” marks the beginning of the painter’s mature career.

Daring, compositionally innovative, and deeply psychological, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp launched Rembrandt to fame and wealth and influenced generations of artists to come. Indeed, without Tulp, it seems impossible for Thomas Eakins to have painted The Gross Clinic, 1876 almost two and a half centuries later.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Mauritshuis

Dolores Mitchell. “Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp”: A Sinner among the Righteous,” Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 15, No. 30 (Nov 1994), p. 145 – 156

Aloïs Riegl and Benjamin Binstock. “Excertps from “The Dutch Group Portrait”,” October, Vol. 74, (Autumn 1995), p. 3 – 35

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Rembrandt, The Night Watch

by DR. WENDY SCHALLER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Rembrandt van Rijn, The Night Watch (Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq), 1642, oil on canvas, 379.5 x 453.5 cm (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

A night watch?

Would it surprise you to find that the title that Rembrandt’s most famous painting is known by is actually incorrect? The so-called Night Watch is not a night scene at all; it actually takes place during the day. This title, which was not given by the artist, was first applied at the end of the eighteenth century. By that time the painting had darkened considerably through the accumulation of many layers of dirt and varnish, giving the appearance that the event takes place at night.

The Dutch civic guard

Rembrandt’s Night Watch is an example of a very specific type of painting that was exclusive to the Northern Netherlands, with the majority being commissioned in the city of Amsterdam. It is a group portrait of a company of civic guardsmen. The primary purpose of these guardsmen was to serve as defenders of their cities. As such, they were tasked with guarding gates, policing streets, putting out fires, and generally maintaining order throughout the city. Additionally, they were an important presence at parades held for visiting royalty as well and other festive occasions.

Each company had its own guild hall as well as a shooting range where they could practice with the specific weapon associated with their group, either a longbow, a crossbow, or a firearm. According to tradition, these assembly halls were decorated with group portraits of its most distinguished members, which served not only to record the likenesses of these citizens, but more importantly to assert the power and individuality of the city that they defended. In short, these images helped promote a sense of pride and civic duty.

Rembrandt was at the height of his career when he received the commission to paint the Night Watch for the Kloveniersdoelen, the guild hall that housed the Amsterdam civic guard company of arquebusiers, or musketeers.

This company was under the command of Captain Frans Banning Cocq, who holds a prominent position in the center foreground of the image (above left). He wears the formal black attire and white lace collar of the upper class, accented by a bold red sash across his chest. At his waist is a rapier and in his hand a baton, the latter of which identifies his military rank. Striding forward, he turns his head to the left and emphatically extends his free hand as he addresses his lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburgh, who turns to acknowledge his orders. He is also fancifully dressed, but in bright yellow, his military role referenced by the steel gorget he wears around his neck and the strongly foreshortened ceremonial partisan that he carries.

Sixteen additional portraits of members of this company are also included, with the names of all inscribed on a framed shield in the archway. As was common practice at the time, sitters paid a fee that was based on their prominence within the painting.

A unique approach

Compared to other civic guard portraits, Rembrandt’s Night Watch stands out significantly in terms of its originality. Rather than replicating the typical arrangement of boring rows of figures (see above), Rembrandt animates his portrait. Sitters perform specific actions that define their roles as militiamen.

A great deal of energy is generated as these citizens spring to action in response to their captain’s command. Indeed, the scene has the appearance of an actual historical event taking place although what we are truly witnessing is the creative genius of Rembrandt at work.

Men wearing bits of armor and varied helmets, arm themselves with an array of weapons before a massive, but imaginary archway that acts as a symbol of the city gate to be defended. On the left, the standard bearer raises the troop banner while on the far right a group of men hold their pikes high.

In the left foreground, a young boy carrying a powder horn dashes off to collect more powder for the musketeers. Opposite him, a drummer taps out a cadence while a dog barks enthusiastically at his feet.

In addition to the eighteen paid portraits, Rembrandt introduced a number of extras to further animate the scene and allude to the much larger makeup of the company as a whole. Most of these figures are relegated to the background with their faces obscured or only partly visible. One, wearing a beret and peering up from behind the helmeted figure standing next to the standard bearer has even been identified as Rembrandt himself.

Three musketeers

While a number of different weapons are included in the painting, the most prominent weapon is the musket, the official weapon of the Kloveniers. Three of the five musketeers are given a place of significance just behind the captain and lieutenant where they carry out in sequential order the basic steps involved in properly handling a musket. First, on the left, a musketeer dressed all in red, charges his weapon by pouring powder into the muzzle. Next, a rather small figure wearing a helmet adorned with oak leaves fires his weapon to the right. Finally, the man behind the lieutenant clears the pan by blowing off the residual powder (both the figure in a helmet with oak leaves and the man blowing off the powder are visible in the detail of the central figures above). In his rendering of these steps, it seems that Rembrandt was influenced by weapons manuals of the period.

A golden girl

Probably the most unusual feature is the mysterious girl who emerges from the darkness just behind the musketeer in red. With flowing blond hair and a fanciful gold dress, the young girl in all her brilliance draws considerable attention. Her most curious attribute, however, is the large white chicken that hangs upside down from her waistband.

The significance of this bird, particularly its claws, lies in its direct reference to the Kloveniers. Each guild had its own emblem and for the Kloveniers it was a golden claw on a blue field. The girl then is not a real person, but acts as a personification of the company.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt’s paintings on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with Saskia

by DR. WENDY SCHALLER

A theatrical flair

In an age of cinematic super heroes and role-playing games, who hasn’t imagined themselves at one time in their life as something other than what they were? The seventeenth-century Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn certainly did. In his 1636 etching, Self-Portrait with Saskia, both he and his wife are shown wearing historical clothing. Rembrandt wears a fanciful 16th-century style plumed beret tilted at a jaunty angle and a fur-trimmed overcoat, while Saskia wears an old-fashioned veil. Such play-acting was not unusual for Rembrandt who only twice represented himself in the manner that was most popular at the time, as a contemporary Amsterdam gentleman.

Whether painting, etching or drawing, Rembrandt, who produced more self-portraits than any artist before him (roughly 75), preferred to show himself in a variety of different imagined roles. You can see him as a soldier in old-fashioned armor, a ragged beggar, a stylish Renaissance courtier, an exotically clad Oriental leader and even Saint Paul.

More than a self-portrait

In addition to serving as one of many self-portraits, this small etching can also be regarded as an example of a marriage portrait. The young woman shown seated at the table with the 30 year old Rembrandt is his wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh. Rembrandt most likely met Saskia while working for her cousin, Hendrick Uylenburgh, an art dealer who had a workshop in Amsterdam. The two married on June 22, 1634 and remained together for thirteen years until Saskia’s untimely death at the age of 30. Surprisingly, it is the only etching that Rembrandt ever made of Saskia and himself together.

The two figures are presented in half-length, seated around a table before a plain background. Rembrandt dominates the image as he engages the viewer with a serious expression. The brim of his hat casts a dark shadow over his eyes, which adds an air of mystery to his countenance. Saskia, rendered on a smaller scale and appearing rather self-absorbed, sits behind him. It’s almost as if we have interrupted the couple as they enjoy a quiet moment in their daily life.

Rembrandt, however, has transformed the traditional marriage portrait into something more inventive. This etching marks the first time that Rembrandt has presented himself as an artist at work. In his left hand he holds a porte-crayon (a two-ended chalk holder) and appears to have been drawing on the sheet of paper before him. By identifying himself as a draftsman, Rembrandt draws attention to his mastery of what was regarded as the most important basic skill of an artist.

Is he drawing Saskia or is she simply there to support and inspire her husband as he works? While the marks on his paper don’t provide conclusive evidence of his subject, it certainly was not unusual for Rembrandt to use his wife as a model. In the years that they were married, she would sit for her husband on numerous occasions.

The etching process

Etching is a printmaking process in which a metal plate (usually copper) is coated with a waxy, acid-resistant material. The artist draws through this ground with an etching needle to expose the metal. The plate is then dipped in acid, which “bites” into the exposed metal leaving behind lines in the plate. By controlling the amount of time the acid stays on the plate, the artist can make shallow, fine lines or deep, heavy ones. After the coating is removed, the plate is inked then put through a high-pressure printing press together with a sheet of paper to make the print. Typically, an artist can produce about 100 excellent impressions from a single plate.

Rembrandt as etcher

Rembrandt is regarded as the greatest practitioner of etching in the history of art and the first to popularize this technique as a major form of artistic expression. His work in this medium spans nearly his entire career with nearly 300 etchings to his name. We see a lot of variety in these works as he renders all manner of subjects popular at the time including history, landscapes, still life, nudes, and everyday life, in addition to portraits.

Typically, Rembrandt used a soft ground that would allow him to “draw” freely on his plate (most early etchers used a hard ground), and many of his early etchings have the immediacy and spontaneity of a rapid sketch. In fact, most evidence suggests that he worked directly on the plate, most likely with a preparatory drawing in front of him to serve as a guide. As with his painted works, he developed a very individualized style that clearly set him apart from his contemporaries. His highly experimental nature led him to explore the effects of using different types, weights, and colors of paper for printing his works.

Rembrandt is also known for his practice of varying the degree to which he etched a plate, an approach seen here. The figure of Rembrandt is more deeply bitten than that of Saskia, a technique that not only suggests that the artist is closer to us, but also places greater emphasis on him. The figure of Saskia, on the other hand, is more lightly etched, with the effect that she is seated farther away and plays a less important role. These differences have led some to suggest that Rembrandt may have etched Saskia first, and then added himself in the front. This notion is supported by the lines of her dress which appear to continue under his overcoat.

Another thing that makes Rembrandt stand out among his contemporaries is that he often created multiple states of a single image. This etching, for example, exists in three states. By reworking his plates he was able to experiment with ways to improve and extend the expressive power of his images.

Additional resources:

This print at the Fitzwilliam Museum

Rembrandt: Prints on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Introduction to intaglio printmaking (MoMA video)

Intaglio process (MoMA video)

Rembrandt, Girl at a Window

A Trick of the Eye

In Girl at a Window we see a young woman, possibly a servant girl, leaning on a stone ledge. She wears a loose-fitting white blouse, fastened with gold braid, her flowing curls crowned by a red cap. She has a rosy complexion, and the paint has been applied with thickly impastoed (thickly applied) paint. She inhabits a dark, ambiguous space, and it is unclear where she is located. What is most striking about the picture, however, is her very direct gaze. She looks straight at the viewer, drawing them into the picture; a fact underlined by the gesture she makes with her left hand, pointing towards herself.

Rembrandt’s painting belongs to a type of picture made popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, in which the sitter appears to be entering the realm of the viewer—by leaning out of a window, reaching out a hand, leaning on a picture frame, drawing aside a curtain or stepping forward. Rembrandt and his pupils became particularly intrigued by the possibilities of trompe l’oeil (literally meaning to “deceive the eye”) in the 1640s (Girl at a Window is dated 1645). Another particularly arresting example of this technique is his Girl in a Picture Frame (below), in which Rembrandt plays on the division between reality and the illusion of the painting.

According to the 18th century French art theorist Roger de Piles, who was also an early owner of Girl at a Window, Rembrandt placed the Dulwich painting behind one of the windows in his house and for a few days passers-by mistook her for a real girl. This anecdote has since been disproven; however, its message echoes the story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius—two Greek painters who staged a contest to determine who was the greater artist. Zeuxis painted a picture of a child carrying grapes and the picture was so realistic that birds were fooled into eating the grapes. Yet, when Parrhasius asked Zeuxis to draw back a curtain to reveal his own painting he realized to his humiliation that the curtain was an illusion; at this point Zeuxis conceded that Parrhasius was the better painter. The significance of this story is to suggest that a good artist can paint realistic animals or objects but only a great artist, like Parrhasius or Rembrandt, can deceive people (or indeed other artists).

Numerous attempts have been made to interpret the subject of Girl at a Window and the identity of its sitter. Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s longtime lover after the death of his first wife Saskia has been suggested as a possible model. Yet Hendrickje would have been 19 in 1645—perhaps too old to be the girl depicted. It has been suggested that the girl may represent a biblical or allegorical figure, perhaps an Old Testament heroine. Her white blouse, with its gold braid, is not the typical attire for a servant and is more likely a kind of fantasy clothing, similar to that worn by other figures in Rembrandt’s history paintings. This type of clothing gives the figure a romantic and timeless quality, suggestive of the past (even if not historically accurate).

During the recent conservation of this painting, the discolored varnish was carefully removed, revealing a bold mixture of colors in the model’s face. Rembrandt often applied his paint with palette knives as well as his fingers. The only surviving drawing for Girl at a Window (below) is drawn from life and sketched confidently using just a few expressive strokes of graphite. The differing position of the girl’s arms in the drawing indicates that the study does not derive from the painting but was in fact produced during its development.

Essay by Helen Hillyard, Assistant Curator at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

This essay was produced in conjunction with the Making Discoveries display series at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. The displays coincide with the release of the Gallery’s Dutch and Flemish Schools Catalogue, published 2016, and aims to disseminate important findings from this major research project.

Rembrandt, Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves: The Three Crosses

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves: The Three Crosses, 1653, drypoint printed on vellum, sheet: 15 1/8 x 17 7/16 in. (38.4 x 44.3 cm) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Additional resources:

Rembrandt, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): The conservator’s eye, Rembrandt van Rijn’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, 1653, oil on canvas, 56 1/2 x 53 3/4″ / 143.5 x 136.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Speakers: Jim Coddington and Beth Harris

What makes this painting so captivating?

In 1961, the Metropolitan Museum paid a staggering 2.3 million dollars to obtain a late work by Rembrandt van Rijn, the painting now called Aristotle with a Bust of Homer. At the time, it was the most money ever paid for an artwork. The painting had taken a circuitous route: from Rembrandt’s studio in Amsterdam to Sicily to London before crossing the Atlantic and finding its home in several private collections prior to auction. Its early travels are well documented, thanks to the survival of shipping manifests and correspondence. The painting now captivates visitors to The Met, as it has captivated generations of art historians who have argued over almost every aspect of the painting. What is it that makes this painting so compelling?

Identifying the subject

The most commonly accepted identification of the subject was first convincingly argued in 1969 by Julius Held and refined in the 2007 Metropolitan Museum catalog of Dutch paintings by Walter Liedtke. Based on a suggestion made by the Dutch art historian Abraham Bredius in the 1930s, Held argued persuasively for the identification of the subject as Aristotle contemplating a bust of the blind ancient Greek poet Homer (who lived some 400 years prior to Aristotle and who is credited as the author of the of the epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey).

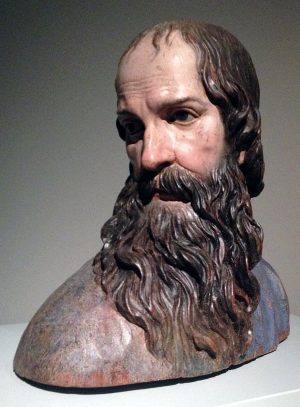

The identification as Aristotle is based on the facial features, long hair and beard, jewelry and elaborate dress. They are all comparable with other images of Aristotle produced in both paint and print in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in both northern and southern Europe. Aristotle was held in high regard not only as a poet and philosopher but also as an important commenter on Homer and the teacher of Alexander the Great. Alexander is said to have counted a volume of Homer’s works as one of his prized possessions.

At the time of The Met’s purchase, the subject of the painting was tentatively identified as Aristotle, but was not yet firmly established. This reflects the confusion also recorded in seventeenth-century sources. The painting was originally purchased (and possibly commissioned) by the Sicilian prince Don Antonio Ruffo for the hefty sum of 500 florins. Whether it was a commission or a purchase is unclear, as is exactly what Rembrandt was asked to provide. If it was a commission, the choice of subject must have been left to the painter since when it joined Don Ruffo’s collection it was described as Aristotle or Albertus Magnus (a thirteenth-century German philosopher). This suggests that even the first owner was uncertain of the subject and that decisions about content must have been made exclusively by Rembrandt.

The painting continued to be documented in numerous family inventories until the late eighteenth century. Over the years, it has been (mis)identified as “a philosopher,” Albertus Magnus, Tasso, Ariosto, Virgil and even the seventeenth-century Dutch poet Pieter Cornelisz Hooft.

The identity of the sculpted bust in the composition was similarly unclear. It was sometimes vaguely identified as representing antiquity, and as an attribute of the central figure. That it was intended to represent Homer can be supported in several ways.

Almost ten years after his purchase of this painting, Ruffo would go on to commission two more paintings from Rembrandt: a representation of Homer (remnants now in the Mauritshuis) and one of Alexander (now lost). The Mauritshuis Homer fragment (above) shows the blind poet isolated, though in its original format it would have included the students to whom he was speaking. The living poet in this painting is virtually identical to the bust in Aristotle. The shape of the face, the framing of the sightless eyes, and the thin band across his forehead correspond with numerous prototypes and support the firm identification of the bust as Homer. Held has even related it to a specific Hellenistic bust type represented by an example in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Rembrandt himself owned a bust of Homer, as it appears in his 1656 bankruptcy inventory.

Aristotle

In the painting’s current state, Aristotle is depicted in three-quarter length. His right hand extends to rest on the sculpted bust placed on a table in front of a mountain of books partially hidden by a curtain, but he is not looking at the bust. His eyes are fixed on an invisible point outside the frame of the painting, his dark eyes and absent gaze contributing to a feeling of melancholy and detached reflection.

Held associated this melancholy with a passage from Plutarch which recounts that Aristotle had fallen out of favor with Alexander; Liedtke sees the melancholy as an appropriate attribute of a man of learning in the seventeenth century.

Aristotle’s clothes seem to belong to no particular period, and Rembrandt has eschewed a more traditional, toga-clad approach such as that found in Raphael’s School of Athens. Aristotle instead seems to wear an odd combination of a wide-brimmed hat, a white tunic, and a dark apron-like garment, adorned not only with a gold chain but earrings and a pinky ring. The bust itself is painted in such a warm tone that it seems almost more like flesh than stone, putting the venerable poet almost within reach. The two thinkers, living and sculpted, are linked not only by Aristotle’s gesture, but by the repeated arcs created by their clothing and accoutrements.

The brushwork

Like much of Rembrandt’s work from the last third of his life, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer uses the rich darkness of the background to set off the central figure, who is gently picked out from the darkness almost as if under a spotlight. Quick, vigorous brushwork creates the voluminous folds of Aristotle’s left sleeve; bright spots of white and light yellow crest to form the shimmering surfaces of the chain draped across his torso.

Though the crux of the painting is the interaction between bust and man, the highlights and surface texture carry our attention across Aristotle’s body to his left hand which, accented by a ring, rests on the chain at his hip. The background, by contrast, dissolves into obscure and ambiguous darkness, possibly enhanced over time.

Interpretations

Held proposed that here Aristotle ponders the temporality of worldly success as represented by the golden chain versus the more profound and lasting benefit of wisdom gained from art and literature embodied by Homer’s bust. In this sense, the formal repetition of the arc created by Aristotle’s chain and Homer’s sculpted clothing establishes the two figures as counterpoints.

Aristotle’s chain bears a medallion featuring a portrait of a man, possibly Alexander the Great. The gifting of gold chains was an ancient practice to recognize excellence and service, and had been revived in the early modern period. It is thus both an historical attribute of the figure and an easily recognizable token of honor for the contemporary viewer. The significance of the chain—both for the subject and in compositional terms—is further made evident through the care with which it was painted.

In the Poetics, Aristotle addresses, among other topics, how poetry, theater, and the arts are processes of mimesis, or imitation of the world. Through imitating the world in a new format, the poet or painter presents a new vision to the viewer and a new way of knowing the world. In selecting Aristotle as a subject, Rembrandt commemorated the role of vision—of painting itself—as a noble art.

Perhaps the appeal of the painting derives partly from the way the viewer is invited to participate and asked to contemplate a subject who, as Walter Liedtke wrote, is shown “not as a sage from whom wisdom emanates, but as a man who contemplates ethical problems and puzzles them out for himself.”

By enabling the viewer to take on the Aristotelian role of the one learning by looking, Rembrandt allows the viewer to engage, like Aristotole, in profound thought. In that regard, it was a perfect piece for an educated, thoughtful collector in the Early Modern period and remains an invitation to look and to learn for future generations of visitors to The Met.

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Rembrandt van Rijn, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, 1653, oil on canvas, 56 1/2 x 53 3/4″ / 143.5 x 136.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Video by The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Additional resources:

This painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Jonathan Bikker, “Contemplation” in Late Rembrandt, Bikker, Jonathan and Gregor J. M. Weber, eds. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2015, pp. 215-233.

Walter Liedtke, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, in Dutch Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 2007, pp. 629-654).

Julius Held, Rembrandt’s Aristotle and other Rembrandt Studies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Rembrandt, Bathsheba at Her Bath

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Rembrandt van Rijn, Bathsheba at Her Bath, 1654, oil on canvas, 56 x 56″ / 142 x 142 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait (1659)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1659, oil on canvas, 84.5 x 66 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with Two Circles

The painter and the painted

An old man in a white cap stares out at the viewer with a penetrating gaze. His left hand holds his hastily painted palette, brushes and maulstick, while his right hand seems to disappear in an unresolved blur into his thigh or the folds of his coat. He wears a red bib over a white shirt, with a fur lined coat on his shoulders. Some viewers perceive a gold chain, usually a mark of high honor, tucked into the folds of his garments.

The right edge of the canvas reveals the edge of the painting the artist is working on, while the back wall is adorned with two enigmatic arcing lines. The painting is not signed and is most likely unfinished. Technical studies suggest that it may have originally been slightly larger, which would have made the painting within the painting more prominent.

This is Rembrandt in the early 1660s —late in his career and during a period when he used thick impasto and dark colors to build up complex and engaging works of art. Scholars have regarded this particular self-portrait, one of many from the last decade of his life, as perhaps the most enigmatic and masterful of them all. It stands out from approximately 80 other self-portraits because of its light-toned background, which emphasizes the strangeness of the two circles that arc across the wall.

Self-portraits as self-exploration

Approximately ten percent of Rembrandt’s output of paintings and prints consisted of self-portraits. This surprisingly high number is even more impressive when you take into account that each print would have existed in numerous copies — perhaps reaching into the hundreds per image.

Why was Rembrandt so captivated with reproducing his own image? Scholars have approached the self-portraits in a variety of ways: as reflections on Rembrandt’s own psychological state, as evidence of the artist’s stylistic and technical development through his life, as a sophisticated technique of self-promotion, and as a means of theorizing about how Rembrandt perceived the role of the artist in society. Fortunately, many of these interpretations can coexist and overlap.

Rembrandt’s almost obsessive relationship with his own visage could be viewed as a process of self-exploration, a way he took stock of who he was at different points in his career. In some ways, this might seem consistent with the seventeenth-century Calvinist mindset within which Rembrandt would have been raised, a mindset that advocated intense personal responsibility for the state of one’s own soul.

Surely, if Calvinist artists were used to routinely scrutinizing their own actions and motives, then also scrutinizing their own faces makes a certain sense (Calvinism became the official religion of the Dutch Republic in 1648). In that regard, many scholars (for example, Perry Chapman) have perceived the self-portraits as deeply personal. This feels very appealing to us as viewers, because we want to try to humanize artists from the past. However, many leading Rembrandt scholars approach autobiographical psychologizing with skepticism because they argue that it is based in an understanding of the self that is rooted in twentieth-century psychological practices.

Rembrandt’s early self-portraits and the many small engraved and etched ones can perhaps be fruitfully interpreted through the application of early modern art theory and ideas about artistic training. As Marjorie Wiesman has noted, when writing didactic texts for painters in the early modern period, authors such as Franciscus Junius (1637) and Karel van Mander (1604) advised artists to examine their own inner emotions so that they would know how to project those emotions into the scenes that they created. Studying the impact of different emotions on bodies and faces was recommended as a means to make a painter a stronger artist. Many of Rembrandt’s early etched and engraved portraits (such as Self-Portrait with Eyes Wide Open) do exactly this, and yet the painted self-portraits (such as Self-portrait with Shaded Eyes primarily) seem to represent him calmly regarding the viewer. We can therefore conclude that he created different self-portraits for different reasons.

The economics of (self) portraiture

Since the work of John Michael Montias on the economics surrounding Johannes Vermeer and the city of Delft, market forces and economic theory have been fruitfully applied to Dutch art of the seventeenth century. In the case of Rembrandt’s self-portraits, we might ask: who was buying all of these self-portraits? If a self-portrait is regarded not as an internally reflective meditation on self and identity as an end in itself, but as a commodity, different avenues of analysis emerge. A self-portrait not only represents the painter visually, but also does so by quite literally showing the technique of the painter. In that regard, they functioned as advertisements that opened the door to future commissions.

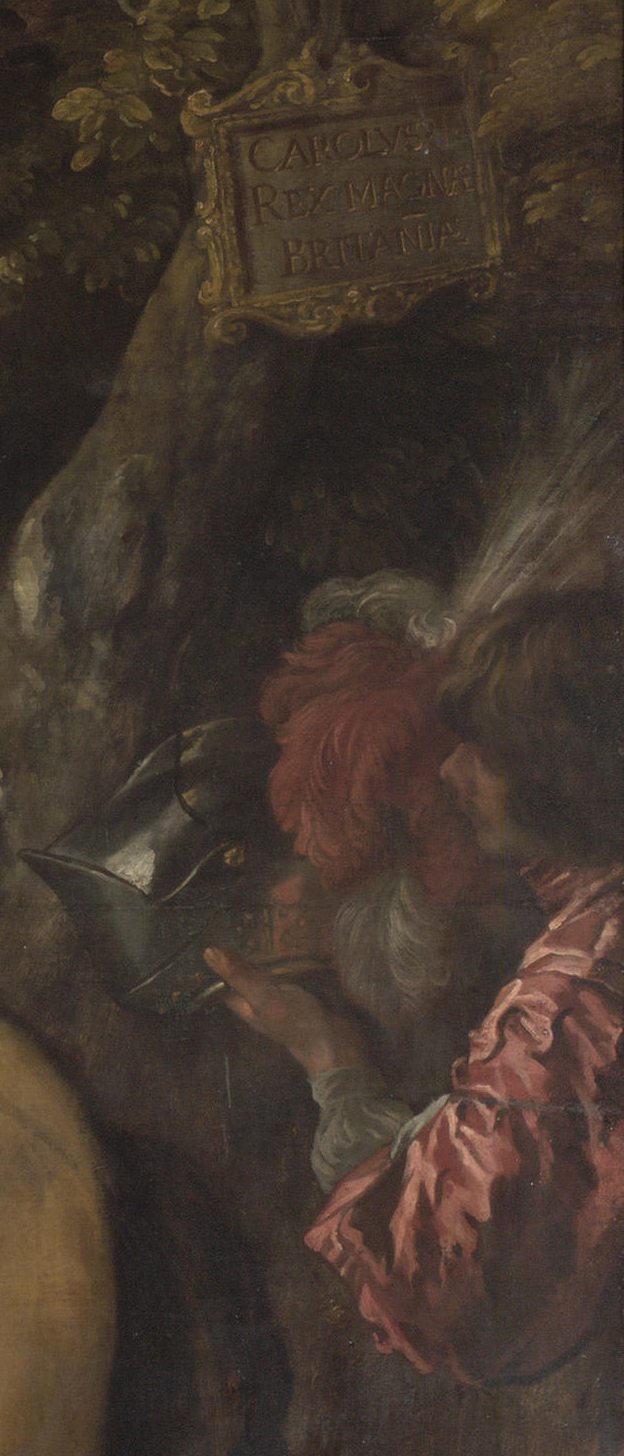

During Rembrandt’s own lifetime, eminent figures such as King Charles I of England, Cosimo de’ Medici, and the art dealer Johannes Renialme were known to have owned self-portraits by the artist. At some points in his career, self-portraits clearly sold briskly. And yet a group of several paintings of generic men in moustaches and hats from the studio of Rembrandt reveal, when x-rayed, that they were self-portraits by Rembrandt to which his students later added accessories in order to convert them to character studies. This implies that the self-portraits were no longer selling and were therefore converted into something that would. The fact that there was not a single self-portrait listed among the art and objects inventoried at the time of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy in 1656 furthers our interpretation of the self-portrait as commodity. If they were primarily intended as personal explorations of the internal life of the artist, surely he would have kept at least one.

Recently, Marjorie Wiesman has approached Rembrandt’s self-portraits chronologically, separating them into earlier, brasher paintings where he appears youthful and passionate, mid-career works where he acknowledges and advances his rise to fame, and later, mature works that ruminate on the nature of old age and art as a profession. Portraits of the late 1630s and 1640s (mid-career) seem to chronicle his rise to the peaks of artistic accomplishment, particularly the famous painted portrait of 1640 and the companion print from 1639 (see above).

In both painted and printed versions of this portrait composition, Rembrandt dresses himself in a gaudy jacket, and chains and brooches adorn his feathered beret. Moreover, he leans on a windowsill with one elbow, inserting himself into a tradition of portraiture used by artists such as Titian and Raphael. He had seen Raphael’s portrait of Baldassare Castiglione at auction in Amsterdam, even noting on his sketch how much it sold for. He was also familiar with Titian’s Portrait of a Man – Gerolam Barbarigo? By mimicking these two great masters in his own self-portrait, Rembrandt’s posture and attire underline that — like Titian and Raphael — he is a man of means and talent. His self-portrait became a tool for advertising to potential investors and securing a place for himself in Amsterdam society and art history.

Self-portrait with Two Circles at Kenwood House

By the 1660s, however, Rembrandt was no longer presenting himself in the same way, perhaps because he was no longer seeking the same kind of audience he had in the earlier parts of his life. Nearing the end of a long and tempestuous career, the late self-portraits take a different, more somber tone. The Self Portrait with Two Circles at Kenwood House is one of the great examples of the last decade of the artist’s life. It has enticed generations of scholars because of the two incomplete circles on the back wall. A definitive explanation for those circles has yet to be agreed upon, but several compelling suggestions have been made.

One interpretation identifies the circles as the two hemispheres shown on a world map of the time. It would not be unusual for a large wall map to be hanging as a backdrop for a painting; wall maps were commonly depicted in the background of seventeenth-century genre scenes by artists like Johannes Vermeer. The problem with this interpretation, according to the detractors (who include Ernst van de Wetering and the Rembrandt Research Project is that the circles are too far apart to represent the two circles of a map, and that the wrinkling and curling of maps on walls seen in other paintings is not present here.

A more philosophical interpretation, proposed by Jan Emmens, suggests that all artists needed to have ingenium (inborn genius), ars (theory or learned knowledge), and exercitatio (or skill gained through practice). In this interpretation, the figure of Rembrandt stands in for Ingenium, while the circles behind indicate theory (ars) and the canvas at the edge of the picture plane speaks to exercitatio.

Perfect circles and artistic greatness

Several other scholars, including B. P. J. Broos and Jeanne Porter, connect the drawing of circles with ideas about art theory expressed in contemporary sources. In Het Schilderboek (The Painting Book) (1604), Karel van Mander repeats a famous story from Vasari — that Giotto could draw a perfect circle freehand at a young age. It is a demonstration of an innate skill, the height of perfection. This type of story, that is, about creating the perfect line, can be traced to classical antiquity where the great artist Apelles was also known for drawing the perfect line. Yet in the Kenwood portrait, Rembrandt’s circles are not perfect circles made with single, fluid lines; they are made up of his more characteristic short, interrupted strokes and they are themselves interrupted by the boundaries of the image.

Ben Broos has suggested that the painting reveals “perfection” in a particularly Rembrandt-esque manner. Rembrandt’s late work is defined by heavy impasto and choppy brushwork. By using that technique to create a perfect circle, the artist appropriates a motif from the tradition of artistic biographies and the legends of artistic greatness but makes it fully his own, both in how it is painted and in using it as a backdrop for a self-portrait. The Kenwood self-portrait could be making a claim for the artist as the pinnacle of greatness, situating himself alongside other masters in the long history of art.

A definitive interpretation of the circles remains elusive, and every generation of Rembrandt scholars proposes a new reading of the motif. What’s yours?

Additional resources:

Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Netherlands Institute for Art History)

The Iconic Art at Kenwood House

P. J. Broos, “The O of Rembrandt,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 4, no. 3 (1971), pp. 150-184.

Perry Chapman, Rembrant’s Self Portraits (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990).

Jeanne C. Porter, “Rembrandt and his Circles: Self Portrait at Kenwood House,” in The Age of Rembrandt: Studies in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting, ed. Roland E. Fleischer, et al. (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988), pp. 188–213.

Ernst van de Wetering, “The Multiple Functions of Rembrandt’s Self Portraits,” in Rembrandt by Himself, ed. Christopher White and Quentin Buvelot (London: National Gallery, 1999), pp. 8 – 37.

Ernst van de Wetering et al., A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4: The Self-Portraits (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005).

Marjorie Wiesman, “The Late Self Portraits” in The Late Rembrandt, ed. Jonathan Bikker (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2015).

Rembrandt, The Jewish Bride

Portrait of a Couple as Isaac and Rebecca, commonly known as The Jewish Bride, is a painter’s painting. According to his letters, Vincent van Gogh was reduced to tears in front of it, writing that he would gladly give up ten years of his life to sit in front of the painting for two weeks, eating only a stale crust of bread. Though modern viewers may require slightly more sustenance, the power of the image remains.

In the center of a horizontally-oriented canvas, a woman in a luxurious red dress stands with her wrists and neck draped in pearls. Her companion stands to her right, one arm reaching behind her, the other reaching out to lay a hand at her breast. He is equally richly dressed in a vertically pleated garment over a shirt in shades of gold and brown. The fingers of her left hand gently rest on his in a touching, protective gesture. The two figures, despite the intimacy of their gesture, do not look at each other, nor do they look at the viewer. They are alone in this moment, set beside an arch and a potted plant barely indicated in shades of dark, mottled brown.

Late in Rembrandt’s career

Rembrandt van Rijn painted this canvas very late in his career. Though born in the Dutch city of Leiden, Rembrandt worked primarily in Amsterdam. There, he built up an impressive local clientele who were eager for his expressive portraits and, later, for his psychologically complex history paintings. His late paintings were intended for a smaller, more selective audience who would appreciate the idiosyncrasies of both the painter and his work. Some scholars have seen the last decade of Rembrandt’s life as a period of decline, yet it is also the decade that yielded many of his most cherished, complex, and psychologically-nuanced works. Paintings from this period are characterized by rich earth tones, in some areas thinly painted and in others applied in a thick impasto.

For example, in The Jewish Bride clearly visible heavy slashes of paint create the texture of the folds of the woman’s skirt, while smaller and more delicate highlights of white and gold pick out the rings on her fingers, the pearls at her neck and wrist, and the decoration of her dress.

The almost sculptural quality of the paint is repeated in the man’s clothes as well. The small, square brushstrokes that form the man’s voluminous right sleeve work almost like tesserae in a mosaic to create a shimmering golden texture. Even the treatment of their faces reveals the hand of the artist moving over the canvas, building up the skin tones from a range of colors. Rembrandt uses the depiction of surfaces and the surface texture of the paint itself to direct our attention, allowing everything less important to literally dissolve into darkness and obscurity.

Who are the sitters?

Portrait of a Couple as Isaac and Rebecca has attracted more than its fair share of theories over the years, with ambiguity on every level. Who is represented? Is this a double portrait or a scene from a narrative? Who commissioned it and where was it hung? Was the canvas cut down at some point, or is this the whole composition? Despite substantial scholarship, many of these questions evade firm answers.

Like Rembrandt’s famous Night Watch, this painting is most commonly called by its nickname, The Jewish Bride. The nickname was a nineteenth-century addition, as there is no evidence for such a title in any seventeenth-century literature. The identification of the subject has generated a great deal of debate. At one point, it was maintained that this was a portrait of Rembrandt’s son Titus and his wife, though other theories have included a father-daughter identification.

Most commonly accepted, however, is the identification of the figures as the Biblical couple Isaac and Rebecca. There are many textual and visual sources that support this identification. The story of this couple is found in the Old Testament in the book of Genesis: Isaac and Rebecca were seeking refuge in the lands of the king Abimelech. Fearing that the locals might kill him because of his wife’s beauty, Isaac claimed that Rebecca was his sister, not his wife. They were, however, caught in a moment of intimacy by Abimelech, revealing their true relationship. Abimelech reprimanded them for their deceit, but also commanded that no one harm them. Isaac and Rebecca are the model married couple: she is modest, beautiful, and obedient while he is faithful, steadfast, and strong in his faith.

An intimate moment

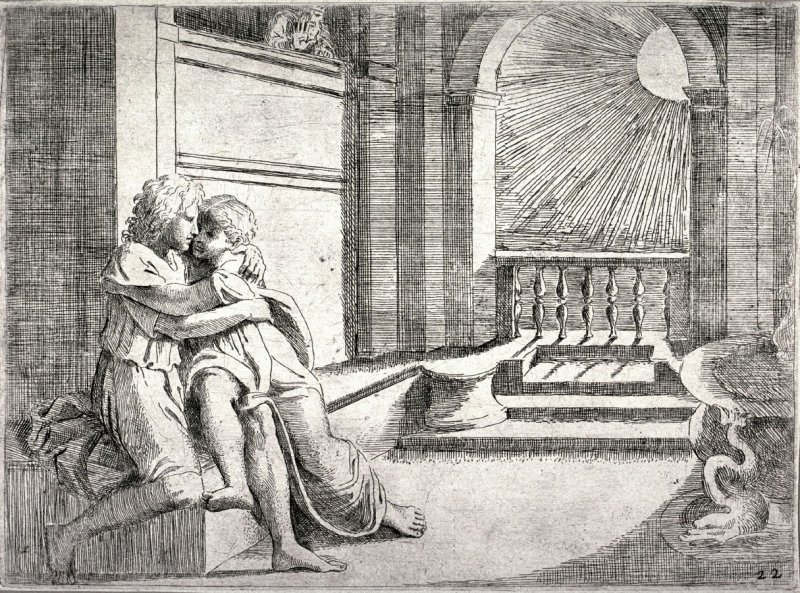

Earlier works by Rembrandt and other artists support the identification of the subject and reveal how Rembrandt evoked and manipulated earlier compositions. A drawing, now in a private collection in the United States, reveals the characteristic and instantly recognizable gesture of the man reaching out to place a caressing hand on the breast of the woman. The earlier drawing differs, though, in that the spying Abimelech is just visible in a window in the top right corner, barely sketched in. In turn, this composition seems to be based on an earlier print by Sisto Badolocchio (above) after a Raphael fresco in the Vatican. Rembrandt’s subject matter therefore has an eminent pedigree.

By altering the composition between the drawing and the painting, Rembrandt has made an important shift in focus. In leaving out Abimelech, he has chosen to focus the attention of the viewer not on the larger narrative, but instead on a moment of intimacy between the two figures. In addition, as Jonathan Bikker has recently pointed out, leaving Abimelech out of the image casts us, the viewer, in the role of the spying king. This directly involves us in the scene, blurring the boundary between painting and life; we, too, are spying on an intimate moment.

A popular type of portrait

The size, lack of scenery, and intimate focus on two figures supports the idea that this was intended as a particular type of portrait: a portrait historié or historiated portrait, where two real people “dressed up” for their portrait.

Having one’s portrait painted in the guise of an historical or biblical figure may seem strange to us now, but the portrait historié was surprisingly common in the Dutch Golden Age (17th century). Whether the patrons were dressing up as biblical figures (and thereby hoping to lay claim to their virtues), or as mythological figures (demonstrating erudition or theatrical ties), historiated portraits existed comfortably alongside the more typical portraits of stern-faced people wearing black.

Jan de Bray depicted his family as figures in the banquet of Antony and Cleopatra, while the children of the exiled king and queen of Bohemia were depicted by Gerrit van Honthorst in the guises of Roman gods. In the case of The Jewish Bride, by choosing to be depicted as Isaac and Rebecca, the sitters were choosing to emphasize their fidelity and piety as well as suggesting to any viewer that their marriage was a happy and virtuous one.

The Jewish Bride is an example of the aging Rembrandt at his finest. He is both perfectly in step with broader trends in Dutch painting such as the portrait historié while also maintaining the distinctive artistic identity that his late patrons appreciated.

Additional resources:

This work in the Rembrandt database

Eclipses in Art › Isaac and Rebecca Spied upon by Abimelech

Bikker, Jonathan and Gregor J. M. Weber, eds. Late Rembrandt. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2015.

Van de Wetering, Ernst. A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings VI. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2014.

Judith Leyster

Judith Leyster, The Proposition

A soberly dressed woman sits in a darkened room, working diligently on her sewing. The only light comes from a lamp on the table, filling the room with deep, ominous shadow. An older man in a fur hat touches her shoulder with one hand and with the other presents a fistful of coins. The sparsely lit and furnished room and the man’s leering countenance generate a sense of unease; the suspended moment leaves the viewer uncomfortable with what has happened—or what is about to transpire. But who are these people? What will the woman choose: to do her work and ignore the man, or to put down her sewing to take the money? Virtue or vice?

Judith Leyster’s painting, called Man Offering Money to a Woman by the Mauritshuis Museum but often referred to as The Proposition, is an enigmatic painting with an ambiguous subject. Painted by one of the few well-known female artists working in the Dutch Republic, its subject matter is unusual in Dutch art, though it has strong ties to several visual and symbolic traditions. Its diminutive size—a mere 30.8 by 24.2 centimeters—invites the viewer to examine it carefully and intimately.

Leyster, Haarlem, and Caravaggio

Judith Leyster lived and worked primarily in the Dutch city of Haarlem, one of the centers of artistic innovation in the first half of the seventeenth century. The city had benefitted from an influx of artists and artisans who fled Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands (now Belgium) during the 80 Years War. Leyster was a member of the Guild of St. Luke (the guild for painters and several other trades), which was unusual for a woman. Like many of her colleagues including Frans Hals, Dirck Hals, and Pieter Codde, she primarily painted scenes of everyday people doing everyday things (otherwise known as genre scenes). Her work is distinctive for the flat background that gives little sense of an illusionistic interior space. Some scholars have attributed this to her possible contact with the “Utrecht School”—artists in the Dutch city of Utrecht who were influenced by Caravaggio whose early genre scenes such as The Cardsharps (below) display similarly flat backgrounds with figures close to the viewer. The sharp contrasts of light and dark on the woman’s blouse and face are also reminiscent of Caravaggio. There are just two visible light sources, the lamp on the table and the glowing foot warmer under the woman’s feet. The flame in the lamp is a form of illumination often seen in Caravaggio’s northern followers (and not in Caravaggio’s own work).

Instilling morality

On the surface, the painting shows an awkward interaction between a man and a woman. Dutch art often seems to reflect everyday life. Yet there are reasons to interpret these images symbolically, and not just as a reflection of life as it was lived. Some scholars (including Wayne Franits and Simon Schama), have interpreted the immense volume of imagery of women as indicative of a general anxiety about women’s education and what it meant to be a good Calvinist housewife. Since religious art was not being produced for the church in this Protestant country, morality had to be instilled in other ways. Secular genre scenes are often perceived as having a role to play in the moral education of the populace, either in presenting an image of ideal behavior or the consequences of bad behavior. Scenes of pious, moral women on the one hand and brothel scenes with lascivious women on the other may have flourished for just these reasons.

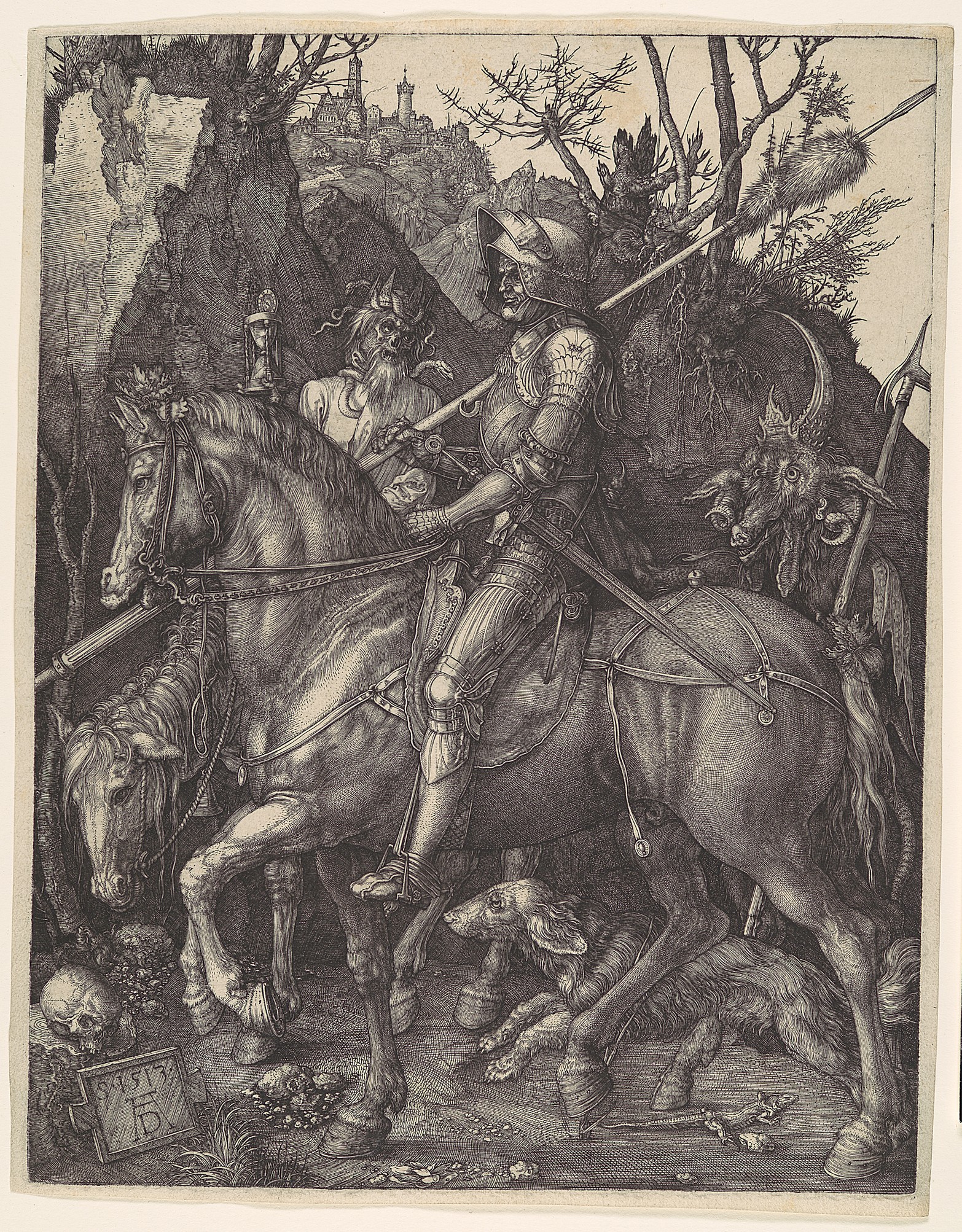

One commonly accepted interpretation of this painting—and the one from which the painting takes its most common nickname—was proposed by a leading scholar who sees the painting as representing a sexual proposition—one which the woman is staunchly ignoring.[1] This is a novel take on a traditional subject—brothel scenes where men interact with prostitutes or men and women drink and make merry in mixed company were among the most common subjects for genre paintings of the early seventeenth century. This type of scene has a long history in northern art (by artists such as Quentin Metsys, Lucas Cranach, Albrecht Durer, and others) and the actions of the participants was presented as unwise, unrestrained, and sinful, and women are usually presented as seductresses and thieves. These paintings therefore are models of how not to behave. By contrast, Leyster’s composition draws on another type of imagery that showed women hard at work—the very model of virtue.

Emblem books

A common component of visual culture in the seventeenth century was a type of book called an emblem book. On one page, the book might contain an image, a motto, and a poem, all explaining one moral lesson the reader was expected to learn. Books of this sort proliferated and some scholars have noted that there were more copies of emblem books circulating in seventeenth century Holland than bibles. Many scholars have tried to use this shared visual language to “decode” the components of genre paintings, with mixed success. Emblem literature was often targeted at specific audiences: for example, Jacob Cats, Houwelijk (Marriage) outlined all the proper stages of life for a woman. In one emblem, he presents needlework as one of the skills most valued and emblematic of domestic virtue.

In Leyster’s painting, the woman becomes an icon of domesticity, working diligently in the cold, unlit room. Even the foot warmer on which the woman rests her feet to combat the cold has been connected to emblem books—as a symbol of the woman’s refusal of the man. One emblem book frames the foot warmer as a woman’s best friend since a man would have to be truly enticing to get a woman to step away from her foot warmer on a cold night. The woman’s firmly planted foot does not indicate a tendency towards a sexual liaison. Leyster’s composition has been seen as an important fore-runner of later genre painters such as Gerard Ter Borch, and, most famously, Johannes Vermeer. In Leyster’s painting, the viewer is left wondering to which tradition the woman belongs. Like much of Dutch art of the Golden Age (the 17th century), this painting is about choices: the choices of the subjects and by extension, the choices of the viewer. The woman is in a suspended state, a moment of decision. Will she virtuously continue her work, or arise, take the money, and go with the man? Will she choose virtue or vice?

[1] Frima Fox Hofrichter, Judith Leyster: A Woman Painter in Holland’s Golden Age (Davaco Publishers, 1989)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Additional resources:

This painting at the Mauritshuis

Judith Leyster at the National Gallery of Art

Leyster on the Google Art Project

Wayne Fronts, Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Frima Fox Hofrichter, Judith Leyster: A Woman Painter in Holland’s Golden Age (Davaco Publishers, 1989).

Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (Vintage, 1997).

Peter Schjeldahl, “A Woman’s Work: The brief career of Judith Leyster,” The New Yorker, June 29, 2009.

Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait, c. 1633, oil on canvas, 74.6 x 65.1 cm / 29-3/8 x 25-5/8″ (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Willem Kalf, Still Life with a Silver Ewer

by STEVEN ZUCKER and BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Willem Kalf, Still Life with a Silver Ewer and a Porcelain Bowl, 1660, oil on canvas, 73.8 x 65.2 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Gerrit Dou, A Woman Playing a Clavichord

A Harmonious Composition

A tapestry is drawn back to reveal a young woman sitting alone in an unlit room. She plays a clavichord, a portable and fairly quiet keyboard instrument, with a decorated lid. Sunlight enters the room through a window to the left, illuminating the figure of the woman and touching on the different still life elements dispersed across the space: an empty birdcage hanging from the ceiling, a velvet cushion on a carved wooden stool, a ewer and basin encircled by a vine, a viol da gamba (the large stringed instrument) and a table with an open music book, flute, platter and wine glass. They are illustrated so realistically that there is a temptation for the viewer to reach out and caress them. The woman looks out towards us as though we have intruded: a momentary interruption of her intimate solo concert. Perhaps, she is awaiting the return of her lover, who will play the viol and join her in a duet. Maybe it is we, the onlooker, who is meant to take her partner’s place.

A Woman Playing a Clavichord was painted by Gerrit Dou around 1665. Dou was the most famous of the group of painters active in the city of Leiden, in the Dutch Republic, who were known as the fijnschilders (literally “fine” painters), who specialized in small-scale paintings full of minute detail and which concentrated on the faithful depiction of different surfaces and textures—a talent that is clearly evident in the Dulwich painting. Dou was the youngest son of a glass-engraver and from an early age trained in his father’s profession. It was this background that doubtless enabled the young Dou to develop his meticulous technique. He began his formal training as a painter in 1628 when he was sent to the studio of Rembrandt, remaining with the master for three years before completing his apprenticeship.

A Woman Playing a Clavichord is regarded as one of Dou’s finest works, and is one of only two paintings that take this musical theme as its subject. The other is A Young Lady Playing the Virginal, c. 1665 (above), and the early histories of the two works have been frequently confused. Indeed, the paintings were first displayed together in 1665, when they were shown in an exhibition organized by Dou’s patron Johan de Bye in Leiden; possibly the first ever monographic exhibition of a living artist.

The paintings show how Dou was able to approach this subject in remarkably different ways. Dou still uses the device of the drawn back tapestry-curtain, delicate rendering of fabrics and textures, and the figure of the woman looking up from her playing (although this is definitely not a portrait of the same woman). However, our eye is drawn to the presence of other figures in a room beyond. Wine is flowing and the woman’s lover already sits waiting with glass in hand whilst another couple sing from songbooks, meanwhile a young serving boy tops up their drinks. The woman in the foreground plays a virginal: significantly louder than a clavichord and presumably intended to accompany the singers. In this way, the Young Lady Playing the Virginal is definitely a noisier and more hedonistic scene than A Woman Playing a Clavichord. In contrast to the intimate affair of the Dulwich painting, here the emphasis is very much on the pleasures of life. Whilst Woman Playing a Clavichord may have alluded to the possibility of a male lover, Young Lady Playing the Virginal makes more explicit the woman’s position as a courtesan-type figure whose role is to entertain men.

Nevertheless, interpreting the intricate layers of meaning in Dou’s paintings is far from straight forward. On the one hand the various still life details can be taken at face value—as a testament to Dou’s meticulous technique when it came to representing the world around him. On the other, each element can be seen as symbolic, and the painting full of hidden meanings. Many of these meanings would underline the idea that the missing “partner” in the Dulwich painting is the woman’s lover, and that the painting has various erotic or sexual connotations.

The latter interpretation, which developed with art historical theory of the 1960s, cites the prevalence of emblem books as a reference point for artists; a kind of book popular in medieval and Renaissance Europe that contained drawings accompanied by allegorical interpretations. In this light, the flute, ewer and bow become symbolic of the male sex; whilst the basin and viol become representative of the female. Likewise, the closed birdcage represents the woman’s virginity which may have already been taken. Critically, the argument against seeing this in such a way is that there are no contemporary sources that confirm such an interpretation for this genre of painting.

Dou’s meticulous style of painting was incredibly influential for both the Leiden painters and the renowned artist Johannes Vermeer, who soon after began to paint his own interior scenes showing women playing keyboard instruments, most notably A Young Woman Seated at a Virginal, c. 1670-2 (The National Gallery, London).

Essay by Helen Hillyard, Assistant Curator at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

This essay was produced in conjunction with the Making Discoveries display series at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. The displays coincide with the release of the Gallery’s Dutch and Flemish Schools Catalogue, published 2016, and aims to disseminate important findings from this major research project.

Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer, The Glass of Wine

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Johannes Vermeer, The Glass of Wine, c. 1661, oil on canvas, 67.7 x 79.6 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Johannes Vermeer, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): Johannes Vermeer, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, oil on canvas, c. 1662 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, 1664, oil on canvas, 42.5 cm × 38 cm / 16.7″ × 15″ (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.)

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\): Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665, oil on canvas, 44.5 x 39 cm (Mauritshuis, The Hague)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Johannes Vermeer, The Art of Painting

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Johannes Vermeer, The Art of Painting, 1666-69, oil on canvas, 130 x 110 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Saenredam, Interior of Saint Bavo, Haarlem

by DR. CHRISTOPHER D.M. ATKINS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{17}\): Pieter Jansz. Saenredam, Interior of Saint Bavo, Haarlem, 1631, oil on panel, 82.9 x 110.5 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art) Speakers: Dr. Christopher D. M. Atkins, Agnes and Jack Mulroney Associate Curator of European Painting and Sculpture, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

This painting at The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Handbook (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2014, p.136).

Catalogue Raisonné of the works by Pieter Jansz. Saenredam (Utrecht: Centraal Museum, 1961), p. 74.

Jeroen Giltaij, “Review: Gary Schwartz and Marten Jan Bok, Pieter Saenredam: The Painter and his Time, 1990,” Simiolus 20, no. 1 (1990/1991), pp. 87-90.

Rob Ruurs, Saenredam: The Art of Perspective (Amsterdam: Benjamins / Forsten Publishers, 1987).

Gary Schwartz and Maarten Jan Bok, Pieter Saenredam: the Painter and his Time (New York: Abbeville, 1990).

Rob Rurrs, “Review: Gary Schwartz and Marten Jan Bok, Pieter Saenredam: De Schilder in zijn tijd, 1989,” The Art Bulletin 72, no. 2 (June 1990), pp. 332-336.

Jan Steen, Feast of St. Nicholas

A holiday for children

In this delightful scene, Jan Steen beautifully captures the joys of a family gathering together in their home to celebrate the Feast of St. Nicholas, still one of the most important holidays on the Dutch calendar. The holiday falls on December 6th and is especially devoted to children. In the Netherlands, on the night before the feast, St. Nicholas travels on horseback over rooftops accompanied by his helper, Zwarte Piet (“Black Peter”), whose name comes from his being covered in soot from the chimneys used to access Dutch homes. Children place their shoes on the hearth and hope to find them the next morning filled with presents and other delectable treats. Families sing songs in honor of the saint and share an abundance of candies, specially baked breads, and sweet biscuits. It is a day full of fun and surprises and even a bit of mischief.

A master visual storyteller, Steen incorporates many of these traditions in his painting while also expertly representing the actions and expressions of the children in this middle class family as they react to the morning’s events.

The boy laughs and points to a shoe held by a young maidservant. The shoe contains birch switches that were used to punish naughty children. Clearly, a tearful boy, to the maidservant’s right, received the shoe as a not-so-desirable gift for his poor behavior.

His grandmother, however, beckons him toward the bed in the back of the room, where it appears that she has discovered a better gift hidden behind the bed curtains. On the right side of the scene, three additional children gaze with wide-eyed amazement toward the chimney through which their presents were delivered. An older brother holds up a toddler for a better view. The toddler hugs a gingerbread version of St. Nicholas, a reminder of who is being honored on this joyous occasion.